Executive Summary

While we often focus on the long-term return of stocks, the reality is that market growth is very uneven, not just due to volatility, but as markets go through long-term cycles called secular bull and bear markets. In the midst of a secular bull market - such as the one that exploded stock prices upwards from 1982 to 2000 - the optimal investment strategy is fairly straightforward - buy-and-hold, buy more on the dips, and dial up the leverage and risk exposure. In the midst of a secular bear market, though, buy-and-hold tends to merely produce the flat returns associated with the overall markets, and instead concentrated stock-picker portfolios, sector rotation, alternative investments, and tactical asset allocation become more effective. Using the wrong strategies in the wrong investment environment can produce poor results - just as many styles of active management generated little to no value and just became a cost drag in the 80s and 90s, so too does buy-and-hold now generate benchmark returns that may do little to achieve client goals. The ultimate key is to match the investment strategy to the market environment, given that such cycles can persist for 1-2 decades at a time. And notwithstanding the fact that a secular bear market has been underway for 12 years, it appears that the secular bear market still has a ways to go - which means its dominant investment strategies still have many more years to shine.

The inspiration for today's blog post was a recent discussion I had with another financial planner, who questioned the recent industry trend towards alternative investments and active management strategies. "It's just a fad," he said, "and will end with heartache as all investment fads do. I've watched it play out over and over again in my 30 year career."

"Not necessarily," I replied, "the secular market cycle in today's market environment is quite different than the one you witnessed for the first half of your career. And not all market cycles favor the same investment strategies."

Defining Secular Market Cycles

Secular stock market cycles are extended periods of time when markets deliver below-average or above-average returns. Often lasting for one or two decades, secular bull and bear markets become an important backdrop to the overall market environment; although shorter term, "cyclical" bull and bear markets (that might last 1-3 years) can both occur within a broader secular bull or bear environment, the secular market serves as an overriding tailwind or headwind that further enhances or reduces market returns.

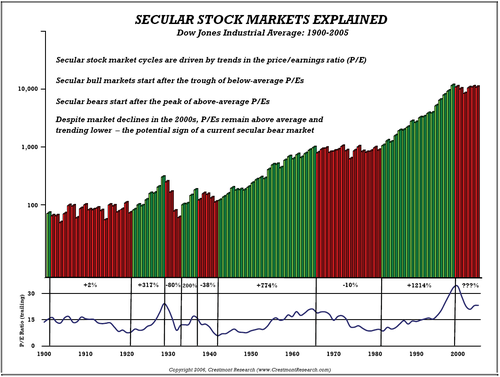

As it turns out, not only do these bull and bear secular market cycles occur with amazing consistency throughout history, but they also occur in a predictable manner: bear market cycles begin once markets reach historically high P/E ratios, and continue until markets reach historical lows, at which point a secular bull market begins, carrying the markets higher and higher until valuation once again reaches a historical peak, and the cycle begins anew. A visualization of secular market cycles over the past century from Crestmont Research is shown below.

As the chart highlights, green sections are secular bull markets where prices rise nearly unabated for an extended period of time. Red sections, on the other hand, represent secular bear markets, where prices typically barely break even, or even finish lower, at the end of the phase. As indicated in the bottom area of the chart, the defining line between secular bull and bear market cycles is when valuation - not prices - make a peak or trough. Coincidentally, it's also notable that in reality, virtually all of the cumulative return for the past 100 years actually came in approximately half of those years - the secular bull market environments. During the other half of the century, markets merely treaded water while the economy and earnings grew, until valuations eventually reached a trough at the lower end of the range so a new bull market cycle could begin.

Secular Market Cycles And Investment Strategies

Because markets go through secular cycles with extended periods of above- or below-average returns over time, the investment strategies that will be most advantageous also shift over time.

In a secular bull market cycle, the optimal strategy is to buy and hold, and buy more on the dips. Returns can be further enhanced by dialing up leverage and/or "risk exposure" to generate even greater returns - given that there is little actual risk, as in secular bull markets any cyclical bear markets recover quickly to make new highs. In point of fact, the end phase of secular bull markets is often marked by a general market euphoria where stocks are seen as virtually riskless, equity exposure is at all-time highs, and margin and other investment leverage is high. As long as the secular bull market continues to persist, these strategies continue to be effective. Until the cycle turns.

When the secular bear market cycle begins, however, the optimal investment strategies shift significantly (and can impact other planning strategies as well). As the earlier chart illustrates, buy-and-hold in the midst of a secular bear market simply leaves the client with roughly the same amount of money one or two decades later (or even underwater after inflation), which may drastically fail to achieve the client's financial planning objectives. Accordingly, as I wrote in "Understanding Secular Bear Markets: Concerns and Strategies for Financial Planners" (FPA membership login required) in the March 2006 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning (with co-author Ken Solow), four strategies are typically popular in secular bear markets to combat the low return environment: concentrated stock-picker portfolios, sector rotation, alternative investments, and tactical asset allocation.

Notably, many of these secular bear market investment strategies haven't been very popular and successful since the 1970s - the last time the markets went through a major secular bear market, leading to the shutdown of many investment funds that couldn't effectively manage through the environment, with a huge boost to the few who did figure out how to survive and thrive (such as Warren Buffett and Peter Lynch). During the secular bull market of the 1980s and 1990s, the strategies were both unnecessary - as the rising tide of the expanding P/E multiples lifted all the investment boats - and generally just resulted in a cost drag for active management that couldn't produce much benefit (because the "benefit" in a secular bull market is dialing up risk and leverage, not actively managing it!).

Looking Back And Looking Forward

For advisors who have been in practice for many years, the reality is that their "early" years of the 1980s and 1990s occurred during a secular bull market, where buy-and-hold-and-buy-more-on-dips is a remarkably efficient and effective investment strategy, and it's nearly impossible for an active manager to shine without dialing up risk (which continues to work until the cycle turns, and it stops working). However, since the market valuation peak in 2000, a secular bear market has been underway, leading to a 12-year investment period where equities have made little or no progress since their year 2000 peak. While some markets have at least broken even or generated a slight positive return with dividends, the reality is that in the preceding 12 years leading up to 2000, the market exploded, with the S&P 500 price level alone rising from just over 300 to more than 1,500 (in addition to dividends) - a remarkable contrast to the fact that now the S&P 500 is still at its 1999 levels!

Given this reality, it should come as no surprise that investors have been seeking new investment approaches to replace the (predictable) failings of buy-and-hold in a secular bear market, and that advisors too feel the pressure to come to the table with better investment offerings, more alternatives, or some other way to generate the returns that clients need to achieve their financial planning goals. And as long as the secular bear market persists, continuing to invest as though it's a secular bull market will continue to result in unfavorable outcomes.

Of course, at some point in the future, the cycle will turn, as it always does, and a new secular bull market will begin. At that time, buy-and-hold-and-buy-more-on-dips will once again become a popular and effective strategy, and active managers will again struggle to add value short of just adding risk. However, history shows clearly and consistently that secular bull markets do not begin until markets regress not just to the average P/E ratio, but to the lows, suggesting that this secular bear market may still have many years left to play out, given a Shiller P/E ratio that is still in excess of 20 (new secular bull markets typically don't begin until the 6-10 P/E range!).

In fact, as Ed Easterling recently pointed out in an Advisor Perspectives commentary, the current Shiller P/E ratios on the stock market are actually still remarkably close to where secular bear markets normally begin, not end - the past 12 years of dismal returns have merely compressed valuations from nosebleed heights down to a level of "merely high". Which means as it stands now, secular bear market investment strategies may still have more than a decade of life remaining.

(Editor's Note: For those interested in reading more about secular bull and bear market cycles, I highly recommend the resources at  Crestmont Research, including Ed Easterling's two books, "Unexpected Returns: Understanding Secular Stock Market Cycles" and his more recent "Probable Outcomes: Secular Stock Market Insights".)

Crestmont Research, including Ed Easterling's two books, "Unexpected Returns: Understanding Secular Stock Market Cycles" and his more recent "Probable Outcomes: Secular Stock Market Insights".)

So what do you think? Do you consider secular bull and bear markets as part of your investment approach with clients? Would you invest differently in a secular bull market compared to a secular bear? Should you?

The chart shows that these cycles can be short or long, and looking backward we can easily tell when they turned, but that is pretty useless in telling when the market will turn NEXT time. Lots of folks understood that we were inflating a huge bubble a few years back and also in the late 1990s, but how expensive is “too expensive”? To time these market changes you have to be right over and over [when to get in/out]. There are dozens of strategies that will work *sometimes*, but I am not aware of any that works ALL the time, especially after costs and over 30 or 50 years of an ‘average’ investor’s career. Index Tracking Error will have a severe career limiting effect on most active managers when the bear turns into a bull, and even for those who are out of synch during a bear cycle.

“The Death of Equities” [1979] anyone?

How about “Every person on the planet (should short US Treasuries)” [Feb 2010]?

“To time these market changes you have to be right over and over [when to get in/out].”

Why? This statement – despite it often being spoken as gospel – is completely untrue. If you intend to beat benchmarks every year, quarter, month, day, then yes, you are correct…quite difficult to do, but also unnecessary. To perform well over longer periods (ie. a full business / market cycle, or someone’s lifetime), however, this is completely false. You simply have to be right when it matters…when bubbles burst and market crises erupt.

Your example from the late 90’s is perfect. Many great managers were ridiculed beyond belief for their “underperformance” during the bubble, depite the fact that they were actually correct in their judgment and process. Their goal isn’t to beat the market every year…they know they don’t have to! They just have to “outperform” when stuff hits the proverbial fan. We have to stop pretending that “beating the market” means you have to beat it every quarter or every year. You don’t.

The use of P/E metrics don’t help a lot if you are trying to beat the market next year, but there is overwhelming evidence of its validity over longer time periods.

Every “active manager” is not trying to time the market. They aren’t all screaming and yelling behind their Bloomberg terminal and rapidly trading in and out of the market. In fact, many of these types of folks are actually more passive than their benchmark.

Further, many openly state something similar to FPA’s Steve Romick, who often reminds us that you must be willing to underperform in the short-term in order to outperform in the long-term. Instead of trying to knock the ball out of the park year after year, they are simply trying to avoid getting killed and letting the market do the rest.

Well written, Michael. Lots of great stuff in here.

Thank you Joe. I did not mean to give the impression that active management is impossible, but it is both rare and extremely difficult, as any study of fund flows will show. Tracking Error makes a lot of “active” managers either closet indexers or unemployed whenever the Assets Under Management flow outward.

Be careful! “Overwhelming evidence” of results is highly dependent on the start and end dates!

It does not matter how well you do for even 30 or 40 years if you retire in 1929 or 1970 or 2009 and your retirement nest egg is cut in half in a very short period.

I started working in 1970 which certainly colors my view of the predictability and reliability of markets. I have lived through Junk Bond and dot.com fads and too many Wall Street scandals to count.

I have read Benjamin Graham and also Jeremy Grantham. As the above article states, following PE works very well sometimes and does not at other times. These cycles vary in length and intensity. Knowing what has worked in the past can be worthless in predicting the future. In my lifetime I have seen average dividends slashed, and both bull and bear cycles far bigger than anyone predicted. We are now retired and can not risk being out-of-synch by betting on ANY strategy, no matter the prior results [we have a 40/60 asset allocation which we rebalance infrequently, including in March 2009].

Good luck to you!

P.S. Here are a couple of quotes from my Investment Policy Statement:

“90% of what passes for brilliance or incompetence in investing is the ebb

and flow of investment style (growth, value, small, foreign).” – Jeremy Grantham

“Over a short time increment, one observes the variability of the portfolio, not the returns”, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Fooled By Randomness.

Is 5 years too short a term? This week’s Businessweek (p. 39):

“The main Bloomberg hedge fund index, which tracks 2,697 funds, fell 2.2 percent a year in the 5 years ended June 30. The Vanguard Balanced Index Fund, which has a 60/40 split of equities and bonds, gained 3.5 percent annually, and the S&P 500 gained 0.2% a year.”

Don’t like hedge funds? Check out S&P’s study at http://www.standardandpoors.com/indices/spiva/en/us .

Note that the 5 years encompasses 3/09, a time when some observers (not the Shiller p/e crowd) saw the market as a screaming buy.

Granted that active management has its periods but can risk averse individuals handle the periods of under-performance? Also, I have yet to see evidence that over a long period, more than 20% of pre-selected (i.e. avoid selection bias) active managers beat their index after all fees.

Robert,

I don’t consider the Bloomberg hedge fund index to be much of a benchmark to evaluate this. That index includes an enormous number of funds with an incredible range of investment strategies.

It would kind of be like evaluating the 5-year track record for all ETFs since 2007, without any distinction about whether they were stock, bond, commodity, real estate, or some other asset class or investment strategy. It just doesn’t tell you much about the efficacy of any particular asset class or strategy result.

Notably, there’s also NO requirement for the strategies discussed in this blog post to be invested using a 2+20 expense structure, which clearly will drag down returns as well. There are alternative, less expensive, ways to invest many of the secular bear market strategies discussed here.

To answer your broader question, though, yes I consider 5 years to generally be a legitimate time horizon for measuring, particularly the last 5 years that include both a bull and bear market (on the other hand, 2002-2007 or 1994-1999 would be less useful, as they’re just bull-only 5-year cycles).

But the bottom line is that the points in this article have nothing to do with hedge funds, per se. Hedge funds are simply one of many vehicles/arrangements to invest some of these strategies.

– Michael