Executive Summary

As the US continues to struggle with its retirement savings woes, a wide range of solutions have been proposed to try and address the problem, with varying degrees of success and adoption. From defined benefit and defined contribution plans, from nudges to mandatory contributions, there is little consensus on the best way forward.

In a new paper, behavioral finance researcher Meir Statman makes the case that the primary reason many proposals have fallen flat is that they do not properly segment prospective retirees, as the needs and issues – and potential solutions – are substantively different depending on whether the target is the wealthy, the poor, or the middle. And even amongst the middle, the needs of the steady earners and savers is far different than those who may have the income by are struggling to save due to spending.

Once viewed from this perspective, Statman finds that many of our current solutions become more clearly ineffective – for instance, annuities don’t help the wealthy and upper-middle who don’t need them, and don’t help the poor and much of the lower-middle who can’t afford them. In turn, Statman suggests that perhaps a better solution is to actually implement a form of mandatory retirement savings – already implemented or being rolled out in many countries around the world – as those who are having trouble making the choice to save may find it “easier” when it is no longer a choice at all, while the wealthy and steady-middle that financial planners already save may be little impacted as they were already likely to save already!

The inspiration for today’s blog post is a recent article by Meir Statman in the latest edition of the Journal of Retirement. In his article “Retirement Income for the Wealth, The Middle, and the Poor” Statman makes a compelling case that our discussions of retirement income have been confused by the fact that different portions of the population have substantively different needs and concerns, and that only be properly segmentation can real retirement issues be addressed.

Segmenting Prospective Retirees

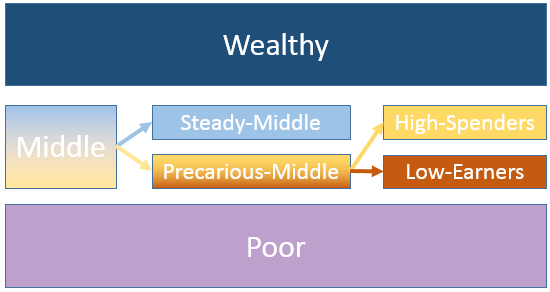

The primary segments that Statman suggests in his article are the Wealthy, the Middle, and the Poor. The Wealthy are those who are able to earn ample income during their working years to save more than enough to fund a comfortable retirement; their retirement concerns (in Statman’s view) will revolve primarily around issues like estate taxes, and status competitions with their wealthy neighbors. The Poor, by contrast, are those who are unable to earn adequate income to save enough (or at all) to fund their retirement.

In the case of the Middle, Statman breaks the category into several sub-groups. At the top are the “steady-middle” who earn adequate incomes to steadily save throughout their working years for their retirement – perhaps not as lavishly as the wealthy, but enough to achieve a comfortable retirement. At the lower end of the Middle are the “precarious middle” who might be close to funding their retirement but are struggling to save enough.

In turn, the precarious middle is broken into two further sub-categories: the “low-earners” who simply struggle to save enough for retirement due to marginal earning power, and the “high-spenders” who might have enough income to theoretically be able to save but spend so much that they don’t have enough for retirement after all.

The graphic below illustrates these retirement income groupings:

Different Needs And Issues For Different Segments

Given these different retirement groupings, Statman makes a compelling case many/most of the solutions around retirement planning and retirement income tend to focus on one group or another in particular, without any acknowledgement of the reality that those solutions may be less effective or totally ineffective for others.

For instance, while annuities are often promoted as a good solution to solve the issue of longevity risk, Statman notes that in practice the Wealthy don’t need them (as they have ample funds to handle longevity risk anyway), and the precarious middle and poor can’t afford them; at best, they’re really only a prospective solution for the steady middle, yet even that group is often so steady and conservative in its spending – allowing them to be in the steady-middle group in the first place – that it’s not clear an annuity solution necessarily helps them, either.

Similarly, other typical retirement planning issues vary greatly amongst the groups. For the precarious middle and the poor, managing $15,000/year of health insurance and medical costs can be problematic or outright destructive to their retirement, yet is often quite manageable for the steady-middle and a non-issue for the wealthy. And overall, the composition of spending itself varies greatly by group, which also impacts their resiliency to adverse economic events; the wealthy and steady-middle tend to have a larger portion of spending that is discretionary and therefore flexible, while the precarious-middle and poor may have little room to adapt to the smallest bumps in the retirement road.

Segmenting Retirement Solutions

In light of these retirement dynamics, Statman suggests that our current policies for supporting retirement may be less effective than we believe. In recent years, retirement policy has tended towards what behavioral finance researchers Thaler and Sunstein have described as “libertarian paternalism” – a midpoint between a purely paternalistic approach (e.g., mandatory retirement savings) and an entirely libertarian one (total freedom to choose to save or not), where the libertarian-paternalistic policies “nudge” people in a particular direction without restricting their freedom (e.g., automatic enrollment to retirement plans with the choice to opt out but the default to participate).

Statman suggests that such approaches have been a benefit primarily for the stable-middle, but that they are far less effective for the precarious-middle and the poor. In the case of the latter, they simply don’t have the cash flow available to save; for the former, low-earners struggle to save as well, and the high-spenders aren’t being influenced enough by the nudge to change their behavior. Accordingly, Statman actually suggests that a more paternalistic approach – similar to what has been implemented or is planned in several countries around the world, including Australia, the U.K., and Israel – may be a better solution.

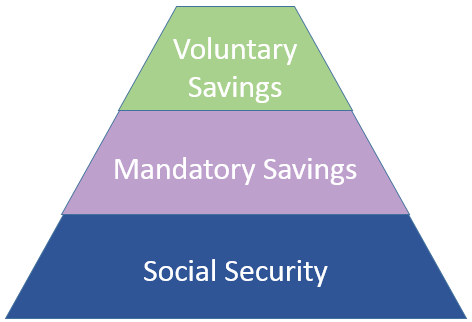

Statman’s version of the paternalistic approach would combine mandatory contributions by employers and employees for a minimum of 12% of earnings, in a 401(k)-like structure but with a central government-agency-supported option for those who don’t have the option via work, with default offerings into a well-diversified low-cost target-date fund. In theory, such an approach would have little impact on the wealthy (they can afford it), and the steady-middle (they would have saved anyway), but may help the precarious-middle (especially the high-spenders group), and could be partially subsidized by the $93 billion/year we’re already allocating to tax expenditures for voluntary defined contribution plans (notwithstanding fears of reducing or eliminating retirement account tax deductions, a recent study of the results when such a change was implemented in Denmark 14 years ago found that in reality only 15% of savers reduced their contributions and 98% of the reduced amounts were simply redirected to another investment account). In essence, the mandatory savings program would form the middle of a 3-layer approach to retirement savings that includes Social Security as a base and voluntary savings on the top.

Statman’s version of the paternalistic approach would combine mandatory contributions by employers and employees for a minimum of 12% of earnings, in a 401(k)-like structure but with a central government-agency-supported option for those who don’t have the option via work, with default offerings into a well-diversified low-cost target-date fund. In theory, such an approach would have little impact on the wealthy (they can afford it), and the steady-middle (they would have saved anyway), but may help the precarious-middle (especially the high-spenders group), and could be partially subsidized by the $93 billion/year we’re already allocating to tax expenditures for voluntary defined contribution plans (notwithstanding fears of reducing or eliminating retirement account tax deductions, a recent study of the results when such a change was implemented in Denmark 14 years ago found that in reality only 15% of savers reduced their contributions and 98% of the reduced amounts were simply redirected to another investment account). In essence, the mandatory savings program would form the middle of a 3-layer approach to retirement savings that includes Social Security as a base and voluntary savings on the top.

While I imagine that many (most?) planners would push back on a mandatory savings approach in lieu today’s voluntary program that allows for more planning flexibility, Statman does have an interesting point that the impact of a mandatory contribution program might be less disruptive than many believe, especially if the impact is partially mitigated by adjusting how some of today’s tax expenditures on retirement are currently allocated.

From a broader perspective, though, Statman does have a compelling point that when discussing retirement planning, strategies, and research, it may be constructive for us to start to clarify which group we’re talking about – though notably, I suspect that most planners consistently work almost exclusively with the Wealthy and the Steady-Middle groups. Nonetheless, as we look overall at what can be done to address the country’s retirement savings challenges, it is perhaps time to take a more nuanced approach and recognize that the tools and strategies that work best for some groups may be doing little to nothing for the others.

So what do you think? Do you find the wealthy/middle/poor a helpful way to think about and frame retirement issues? Would you ever support a moderate mandatory savings program as a “middle layer” of retirement above Social Security and below purely voluntary savings?

I think think it would be difficult if not impossible for the precarious middle to save 12% of their income (i’m assuming employers would reduce/limit compensation–employees would shoulder this expense) I remember chatting with a co-worker years ago–a single mom–about putting enough in her 401k to receive the employer match. She just could not afford even the 6% for the match.

Perhaps boosting Social Security benefits would be a better strategy.

I am a big fan of Thaler’s libertarian paternalism construct, and I think it is a good fit here. As I’ve siad other places, we could auto-enroll everyone into the TSP and make employer & employee payroll deductions the same way we’re making FICA deductions. Employees can opt out at any time and employers can opt out if they offer a cost-effective 401(k) and make similar mandatory contributions (though most would prefer to let the Feds shoulder this burden I imagine). In my mind small businesses would jump at the opportunity to pass along the administrative burden of establishing, monitoring and paying for a 401(k), and those who wished to do so could still fund a traditional profit-sharing or DB plan.

Statman’s groupings are very much on point. “Simply” looking at the financial planning issues (and not the policy issues) it is a good fit. Two areas I’ve looked at in depth in the last year are great examples: (1) financial planning tips for people who hit temporary unemployment and (2) reverse mortgages. In building what turned into a 30-page compendium of unemployment tips the groupings were constantly in play. Topics like file for unemployment ASAP vs negotiating severance contacts. Likewise with applications of reverse mortgages, where I keep talking about the “spectrum of clients” in terms and have made charts explicitly aligning with Statman’s four groups: for example noting that putting a fresh bunch of cash in the hands of high spenders may not be the best long-term financial planning advice while a “standby line of credit” may be a very valuable tool for “steady middle” or moderately wealthy. Same tool that may be hazardous in some hands is a great fit in others.

I like the wealthy/middle/poor paradigm; however, I think that the entire discussion

should be reframed. Instead of “retirement” the focus should be on

“financial security”. Young people and even many middle aged

Americans cannot imagine themselves in five or ten years let alone thirty

years. I’ve had success enrolling millennials in 401k plans by framing and

focusing the message on “financial security”. Whether one is 22 or

92, financial security is one goal on which all Americans agree. 401k or any DC

plan is merely a tool to achieve goal.

Agreed

Love the “financial security” framing idea. It’s great because instead of focusing on something obscure and far out like “retirement”, you are actually focusing people on the second level of maslow’s hierarchy of needs

This is a very helpful categorization of the retirement marketplace. However, I do not trust “progressive” government in this area at all and would point to three examples, namely the “systematic rape” of Social Security, the redistributionist rhetoric that classifies the deductibility of all retirement contributions as a “cost” to the government, and the deliberate and pernicious effects of QE on savers and bondholders. That said, government encouragement and support are obviously essential, and some aspects of retirement planning should obviously be mandatory if “the middle” is to have any chance at all. However, big spending “progressives” have and will suck up every tax dollar, plumb every retirement tax break for “reform” and will champion high inflation to ease the payback of the government’s debt. Government support of retirement planning will not occur in the present environment.

I am familiar with the Australian system of mandatory retirement savings. It has had the support of both progressive and conservative governments, and the overwhelming percentage of the population. It as been enormously successful. Nearly all Australians will retire with a very comfortable amount of savings. And it has only helped the financial advising industry because such a large number now are in the “steady middle” and want advice on how to best invest their several hundred thousand dollars.

I think corporations should be forced to offer pensions. It worked well for so many years. Then they got greedy.

WHAT GARBAGE. THIS IS NOT ABOUT RETIREMENT INCOME,

IT’S ABOUT THE DIFFERENCE BETWEN PEOPLE WHO LIVE RESPONSIBLE,THOUGHTFUL AND DISCIPLINED LIVES AND THOSE WHO DON’T.