Executive Summary

Conventional investment wisdom suggests that dollar cost averaging is a good approach to allocating investment dollars over time. By always investing a constant dollar amount, the strategy ensures that fewer shares will be bought as prices rise, while more shares are purchased if prices decline, bringing down the average cost per share in the long run. The only question is over what time horizon it’s best to average in.

Yet as it turns out, the answer is “none”. In reality, a dollar cost averaging investment strategy doesn’t actually enhance returns in volatile markets that have similar upside gains and downside losses on a percentage basis. And given that on average, markets go up more often than they go down, choosing to dollar cost average is more likely to just leave gains on the table (and the longer the time period, the greater the risk of foregone returns).

However, while dollar cost averaging may not be likely to enhance returns in the long run, it is still a risk management technique. Over the dollar cost averaging time period itself, the diversification of the “new” investment and “old” investment may actually produce superior risk-adjusted returns. And given that the pain of losses is more severe than the joy of gains, risk-averse investors may prefer to dollar cost average simply to minimize the potential regret of not doing so and seeing markets decline shortly thereafter.

Nonetheless, for investors who are comfortable with the risk of their portfolios, and aren’t specifically seeking a “regret aversion” (or at least, regret minimization) strategy, in the long run the best time horizon for dollar cost averaging is simply to invest all the money immediately – at least, presuming the investment was desirable to own in the first place!

Definition Of Dollar Cost Averaging Versus Lump Sum Investing

The definition of Dollar Cost Averaging (DCA) is an investing strategy of allocating a fixed dollar amount to buy a particular investment at regular intervals. By always buying a constant dollar amount, the approach will purchase fewer shares if prices rise, and more shares if prices fall. Given that a larger number of shares are purchased when prices are lower, this approach has the end result of decreasing the dollar average cost per share in volatile markets.

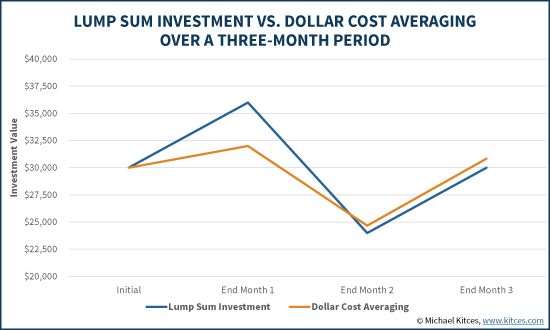

Dollar Cost Averaging Example. Assume an investor wants to allocate $30,000 over the next three months, and is trying to decide whether to do so by purchasing $10,000/month at regular intervals, or just investing all $30,000 at once. The current price of the investment is $100/share, and as it turns out the price rises to $120/share after the first month, falls to only $80/share at the end of the second month, and then returns to its original $100/share price at the end of the third month.

If the investor allocates the lump sum all at once, 300 shares at $100/share are purchased, and the final value of the investment will be worth the same $30,000 as the original investment (given that after all the volatility, the share price ends at the same $100/share it began at).

On the other hand, if dollar cost averaging is used, the results are different. The first $10,000 allocation purchases 100 shares at $100/share. The second $10,000 allocation buys only 83.33 shares (assuming fractional shares are permitted) because the price has risen to $120/share. The third $10,000 buys 125 shares at only $80/share. Thus, at the end the investor owns 100 + 83.33 + 125 = 308.33 shares, which at a $100/share final price is worth $30,833. In other words, the investor finishes with $833 more in wealth, and an average cost/share of only $97.30 (having bought 308.33 shares for $30,000 of total funds). (This also assumes that the funds not yet invested were simply held in cash at a yield of 0%.)

For those who are making systematic contributions to an investment account over time – for instance, ongoing monthly contributions to a 401(k) plan – the reality is that the process of dollar cost averaging happens naturally as steady dollar amounts are contributed.

However, some investors who have a large lump sum dollar amount to contribute – for instance, for the liquidation of a prior investment, the receipt of a windfall, the rollover of a retirement plan, or even just a significant change in investment holdings (leading to a large potential “lump sum” allocation to a new investment) – the opportunity arises to DCA not just as a natural occurrence, but as a proactive strategy. In other words, while a 401(k) participant who is saving $500/month generally only has the means to add $500/month, an investor with $10,000 or $30,000 or $100,000 or even $1,000,000 to invest all at once truly has the choice about whether to invest as a lump sum, or to dollar cost average instead.

Why It Doesn’t Necessarily Enhance Returns To Dollar Cost Average

While the above example showed how a dollar cost averaging investment strategy can result in a positive return over time, even in “flat” markets, the reality is that dollar cost averaging isn’t necessarily a likely return enhancer over time.

The first reason that dollar cost averaging is often overstated is the illusion of viewing returns in dollar amounts, versus percentages.

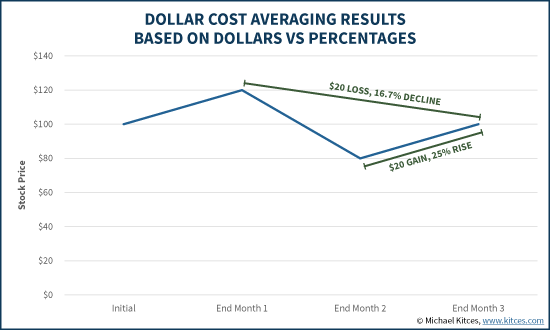

For instance, the example above highlighted a stock that “symmetrically” had a $20/share gain above the starting price, then fell $20/share below the starting price, and finally returned to the original $100/share price. However, on a percentage basis, relative to the amount of money being invested, this volatility was actually not even. The investment shares that were purchased at $120/share and fell to $100/share “only” declined by 16.7% (a $20 loss on a $120 purchase), while the shares that were bought at $80/share and rose to $100/share actually appreciated by 25% (a $20 gain on an $80 purchase). Thus, it’s not surprising that it looked “good” to dollar cost average – the example was actually designed in a manner where the lower priced shares went up by more than the higher priced shares declined!

In other words, the comparison of dollar cost averaging versus a lump sum investment was the difference between allocating 100% as a lump sum into an investment that returns 0% (from beginning to end), or allocating 1/3rd each into three investments, which separately have returns of 0%, -16.7%, and +25%. In this context, it’s not surprising that the dollar cost averaging example looked better, because that scenario already assumed that the DCA approach would have higher returns!

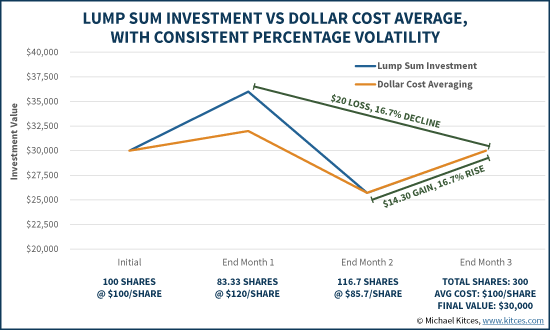

Alternatively, if dollar cost averaging is examined, assuming the average percentage return is the same across each of the scenarios, suddenly the dollar cost averaging benefits vanish. For instance, if the underlying investment is assumed to have a decline of 16.7% from the peak to the end, and also a 16.7% rise from the trough to the end, and you run that scenario through a dollar cost averaging calculator, the outcome is different.

As the chart above shows, when the returns average out in the end (as properly measured in percentage terms), the average cost per share averages out as well, the final result is that dollar cost averaging is no better (nor any worse) than simply having invested a lump sum in the first place!

How A Dollar Cost Averaging Investment Strategy Actually Reduces Returns On Average

Unfortunately, while dollar cost averaging doesn’t actually help in volatile markets with returns that average out (on a percentage basis), it turns out that choosing to dollar cost average is more problematic… because on average markets aren’t just volatile but flat. Historically markets go up far more often than they go down.

And with markets that just keep going up, DCA is inferior to just investing a lump sum right from the start – because the longer the investor waits to invest, the higher the purchase price and the fewer the shares that will be purchased. In other words, all of the preceding examples of dollar cost averaging assumed that the market would fall below the original lump sum purchase price, giving an opportunity to buy it at lower prices. Except in practice, this often doesn’t happen.

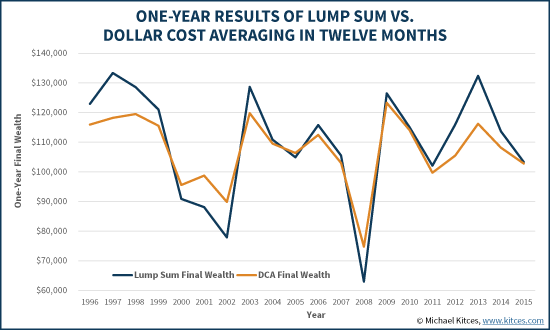

As another dollar cost averaging example, the chart below compares two scenarios: in the first, an investor with a recent windfall invests a lump sum of $100,000 at the beginning of the year. In the second, the investor dollar cost averages in throughout the year, with a $8,333/month purchase at the beginning of each month for 12 months. Investments are made into the S&P 500, and money yet not allocated is assumed to earn a 1-year Treasury (i.e., money market) yield. Investment results are calculated based on final wealth at the end of the first year (as from that point forward, both portfolios will be fully invested and earn the same future returns).

As the results reveal, because markets go up far more often than they go down, most of the time dollar cost averaging doesn't help, and is just an outright losing proposition. Investing evenly throughout the year just buys in at higher and higher prices resulting in less final wealth than simply investing in a lump sum at the beginning of the year. In fact, over the past 20 years, using dollar cost averaging only “won” five times – in 2000, 2001, 2002, 2005, 2008. In retrospect, this is not surprising. Four of these five years were outright bear markets where stocks finished down for the year, so it's not surprising that the slower the money was invested, the more time was permitted for the declines to occur, and the cheaper the investment got! In only one year did the markets finish up and DCA was still superior - in 2005 - and the outcome just barely favored dollar cost averaging, and only because the market ended out declining significantly in the first few months of the year and then made up virtually all of its returns for the year in just the last two months.

On the plus side, this shows that dollar cost averaging can win, at least in scenarios where markets decline. Nonetheless, the dollar cost averaging scenario only “won” 25% of the time, and only materially won in scenarios where there was a significant market decline for the year, which wouldn’t have necessarily been known in advance. And of course, if the investor really “knew” there was a bear market coming, DCA investing still wouldn’t make sense – instead, the investor would just keep the money on the sidelines, and invest it later after the “known-to-be-coming” bear market had occurred!

It’s also notable that because of the simple phenomenon that stocks go up more often than they go down (why else would we invest in them!), dollar cost averaging isn’t necessarily any better when done over a shorter time period (e.g., three months) or a longer time period (e.g., 12 months). At best, markets that go down for longer periods of time fare better with longer time periods for dollar cost averaging (as it simply keeps more money on the sidelines for the bear market), but this still only occurs in a minority of scenarios, and not known in advance. Conversely, 3-month dollar cost averaging tends to perform slightly better than 6-month dollar cost averaging, again for the simple reason that funds are invested more quickly into markets that most often go up and not down (yet on average 3-month dollar cost averaging would still be expected to come out slightly inferior to just investing the lump sum all at once, for the same reason).

In other words, from a return-enhancing perspective, dollar cost averaging continues to be a losing proposition. Dollar cost averaging only leads to better returns when markets decline, yet ironically if markets are known in advance to decline, it would be better to wait to invest altogether, and still not dollar cost average! And in situations of uncertainty, given that return are positive more often than negative, it will generally be a “losing bet” to keep any money on the sidelines rather than just invest it all as soon as possible.

Using A DCA Investment Strategy For Risk Management And Regret Aversion

While dollar cost averaging is more likely to give up returns than enhance them on an absolute basis, DCA strategies can potentially still be relevant for risk management purposes.

The first reason that dollar cost averaging matters for risk management is the behavioral economics phenomenon first popularized by Kahneman and Tversky that we experience more negative pain around losses than we find positive affect from comparable gains. This is significant in the context of dollar cost averaging, as it means that while most of the time we may give up a little upside by averaging into an investment, if we can avoid a significant loss (with exponentially more pain) it may still be worthwhile, even if it happens infrequently. More generally, this means dollar cost averaging can have positive utility when accounting for the (limited) joy of gains and the (significant) pain of losses, even if total returns are likely to be reduced in the long run.

Similarly, because investors are more averse to losses than happy about gains, an investor uncertain about whether to dollar cost average or not may be more likely to regret not dollar cost averaging (and experiencing a greater loss) than proceeding with dollar cost averaging and missing out on an upside gain. Or viewed another way, psychologically speaking if the investor wants to avoid the pain of regret by getting the decision “wrong”, the safer route is to DCA (and risk losing upside) than to lump sum (and risk greater downside), even though it’s not likely to be necessary.

In addition, over a limited one-year time horizon, the reality is that choosing to dollar cost average is similar to a mini-case-scenario of investing into an “all-equities” portfolio versus one that is more diversified. In other words, for an investor trying to decide whether to allocate $100,000 immediately to equities, or dollar cost average in $8,333/month over the next 12 months (with the remainder staying in fixed income until invested), the former scenario will be entirely dependent on equities while the latter will on average be only a 50/50 stock/bond portfolio.

And since more diversified portfolios can have better risk-adjusted returns – at least when the mixture of assets are not perfectly correlated to one another, which is the case with stocks versus bonds or cash – the end result of dollar cost averaging in for a limited period of time is that the portfolio may have better risk-adjusted returns (though still lower absolute returns) over that time horizon.

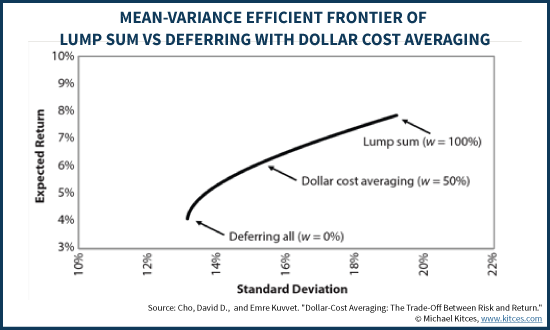

In fact, when we look at the 20 one-year returns of the dollar cost averaging examples earlier, versus the lump sum investment outcomes, we find that the average return was 1.40% lower with dollar cost averaging (on average), but the standard deviation of the dollar cost averaging scenarios was also significantly lower (reduced by 2.21%). In other words, DCA investing was able to bring down the volatility of the investment by slightly more than the reduction in the return alone, producing an enhancement to risk-adjusted returns along the way. Similarly, a recent study in the Journal of Financial Planning, entitled “Dollar-Cost Averaging: The Trade-Off Between Risk And Return” by David Cho and Emre Kuvvet, also found that the range of dollar cost averaging scenarios can produce an efficient frontier of possible portfolios that will have lower absolute returns but may have slightly better risk-adjusted returns.

Notably, this also implies that the best way to enhance the risk-adjusted returns over the dollar cost averaging time horizon is to ensure that the investment being averaged out from has a low (or ideally, negative) correlation to the investment being averaged into. For instance, dollar cost averaging into equities will work better if the funds are deployed from cash (which has a near-zero correlation to equities), or even from mid-to-long term government bonds (which historically has a slightly negative correlation to equities during times of market volatility); conversely, this also implies that there’s very limited value (from an expected return or risk management perspective) to dollar cost averaging from one risky investment into another (e.g., from one type of equities to another).

Of course, the caveat to viewing this even from the risk-adjusted return perspective is that if the investor was already comfortable to invest a certain amount of money in equities (ostensibly as a subset of a larger portfolio), there’s arguably little reason to further lower the risk of that allocation by dollar cost averaging it into the market. For instance, if an investor had decided that a 60% equities and 40% fixed allocation for a “new” portfolio was already consistent with their tolerance and capacity for risk, there shouldn’t be a need to further reduce the risk of the 60% equity allocation over the coming months or year by dollar cost averaging into that 60% equity slice.

Nonetheless, the point remains that for investors who are highly risk-average – or perhaps especially for investors who are highly regret-averse about potential losses – it may still be worthwhile to consider a dollar cost averaging investment strategy as a regret minimization technique. However, because DCA investing is still more likely than not to just give up returns in the long run, it still “pays” to keep the dollar cost averaging time window “as short as possible” – in other words, just long enough to minimize the risk of a significant regret scenario.

So what do you think? Do you use dollar-cost averaging strategies when investing with clients? In what scenarios? Do you recommend dollar-cost averaging as a way to enhance returns, to reduce risk, or simply to minimize the potential for psychological regret?

Any chance you can add value averaging (edleson) to the analysis

Joe,

I have used value averaging with some success for large lump sum deposits, but it is still not a given all the time.

DCA is most often used by those who cannot invest a large lump sum all at once but rather need to build up their investment account over time. It also has the behavioural advantage of letting people know they are buying more shares when prices decline. This can keep investors from emotionally over reacting and making bad timing decisions by selling when they should be buying.

Exactly. Very few people in their working/family-raising years have a lump sum to stash away. This is the beauty of 401(k) investing, using a DCA strategy. I’d hate for the smarty-pants crowd to start using arguments like this as a reason to avoid making contributions.

If you don’t HAVE a lump sum to invest, this discussion is entirely moot. The point is “if you have the money to invest, should you spread it out (via dollar cost averaging) or not”.

That aside, if you want to go down this road, all it really means is “don’t spread out your contributions, put in as much as you can as quickly as you can.” In other words, “dollar cost averaging” still isn’t better. Investing every dollar you can as soon as you can is better. If it just so happens you only GET those dollars to invest over time, you invest what you’ve got when you’ve got it. 🙂

– Michael

Michael

This is a great point.

Indeed you can also highlight the impact when a retiree needs to draw on their savings. Instead of reducing the risk, the regular payments increase the risk.

Most retirees don’t have the option not to drawdown (they need the income) so they have the additional risk to manage. (One form of sequence risk)

Cheers

Aaron

You are leaving out the fact that some people can’t just invest huge lump sums of money all at one time. Typically, in my experience, those who are dollar-cost averaging are funding the investment by means of a consistent income (paycheck) and doing so as a part of a disciplined savings plan. I don’t understand the point of your article, as it implies people have a bunch of cash and just decide to DCA… That doesn’t happen in my experience. Maybe for someone who has been saving in cash and is nervous about the market, and wants to “wade into it”. As an answer to your last few questions… we only recommend this as part of a systematic savings plan. Which actually does improve results in the long-run. Again, it’s not as common for people to have huge lump sums of money each year to invest.

Yes, many people do have lump sums to invest and do this. It could be a rollover from a retirement account that was liquidated to cash. It could be an inheritance. It could be life insurance proceeds. It could be the settlement of a lawsuit. Sometimes we even see this behavior when people are simply switching investment providers or advisors.

If you don’t HAVE the money to invest, obviously it’s a moot point. You invest what you can when you can. Nonetheless, the point remains that if you DO have the dollars to invest, and CHOOSE to spread it out, you’re once again taking an inferior-return dollar cost averaging strategy…

– Michael

How does this relate to someone who is “building a position” in a stock? Does it ever pay to buy 1/3 at a time of a “full position,” or are you better off going all the way in one step? Is this same or different that DCA as discussed in the blog?

Same principle, same conclusion.

If you’re optimistic about the stock, buy 100% now. If you’re pessimistic, don’t buy it. Dollar cost averaging into the stock is a losing proposition from a return perspective. At best, it will help you manage the risk of regret if it turns out (after the fact) that your investment was poorly timed. But on average, it won’t be.

– Michael

Michael,

You are completely ignoring your own statistics in this article – “lump sum investing loses 25% of the time.” Have you ever been to Vegas and lost all your money because something that only had a 25% chance of losing came up 3 times in a row. Even in a coin flip (50/50 chance) starting with 100 people there can be 3 people who got heads 5 times in a row.

As you might suspect in the world of investing we have no idea what is going to happen tomorrow so we don’t make a large bet (with a lump sum deposit) on one outcome. Just like the smart person does not put all their money in a Roth or Trad IRA just because they think their tax rates might be higher or lower in retirement – you diversify your strategy. You put some of your money in now, say 50%, or even 75% (to match your risk,) and you DCA the rest.

It’s just common sense, we never try to out think the market, like believing it is always going to go up on our watch.

Also, the larger the lump sum, the more that 25% risk of loss can affect you. If I got a $1 million dollar inheritance I certainly wouldn’t go out and put it all in an index fund the following day, or any day for that matter. I would invest it over some time frame.

Dave

Dave,

If you want to go with a Vegas example, following a DCA strategy is like betting in Vegas. Lump sum investing is like skipping Vegas.

Skipping Vegas wins, because mathematically betting ANYTHING in Vegas is a losing bet in the long run.

What you are expressing here is a deliberate desire to pursue strategies that result in LESS wealth in order to minimize regret. That is a valid regret minimization strategy – as discussed in the article. But it’s still the mathematical equivalent of making a losing bet. The fact that some people win in Vegas doesn’t mean it’s a good deal to bet big in Vegas. The fact that some people win with DCA doesn’t mean…

– Michael

Michael,

I believe you are equating what will happen over 50 to 100 years in the market with what will happen over your immediate investing time frame before the investment needs to be sold. The fact remains that those are items you can not know and you have to be mindful of the risk involved in investing and that markets are not assured to go up in your investing lifetime, which you cannot predict either.

My only point was to say, on items you cannot predict it is not best to go all-in thinking your strategy will pay off for you. Many fortunes have been lost thinking that will happen.

Let’s use what might be called an “anti-Vegas” mathematical model which would be the equivalent of the “houses” side of the equation where the house “almost always” wins in the long run. If you were a small casino with $1 earnings per year would you allow someone to walk into the casino and put down $20 million on red on the roulette wheel knowing you will win in the long run?

Dave

Great article. Are you aware of Value Averaging? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Value_averaging. I am road testing this on my own portfolio before I roll it out to clients…….

An obvious disadvantage to DAC is that while money is on the sidelines, it is not earning dividends. Clients easily grasp this aspect

Great article, Michael and thank you for updated research. For our clients who have a lump sum to invest, we always recommend buying lump sum vs. DCA. Only a few of our clients have the behavioral subset of buyer’s remorse and only then do we DCA.

What about the converse? Monthly DCA on the sell side when clients are in the distribution phase vs. waiting until late December to take an RMD? Assume that the client does not need the monthly income and could wait until year end. Also, would like your thoughts on staying fully invested and selling in December for RMDs vs. allowing dividends to go to cash inside the IRA over the year to fund the RMD. Assume client’s risk tolerance allows for having to sell more shares year end if the market is down if choosing the stay fully invested/reinvest dividends until time to sell route. I’m wondering if there is any research on this topic with dividend paying investments vs. the real risk of such a short time horizon to take RMD every year. Of course, if the client is investing the net RMD back in a non-qualified account and the market is down at least they will be buying when share prices are down also so I would think it’s a wash. I look forward to your thoughts and thank you. Your blog is one of my favorites.

Jennifer, you address a topic of great interest to me in retirement and facing mandatory distributions from my IRA with annual cash to IRS. You wrote: “Monthly DCA on the sell side when clients are in the distribution phase vs. waiting until late December to take an RMD? ” I understand that in most years the market rises, but I don’t have the nerve to wait until December to pay IRS and to replenish the cash in my IRA. If I did that, I might have to sell when the market is down. Monthly DCA doesn’t appeal to me either. (In DCA, I invested a fixed amount of cash periodically, receiving a variable number of shares.) That DCA works so well for so many people, and worked well for me in my accumulation phase, doesn’t imply to me that it would work well in the distribution phase. So, my procedure is this: Each quarter, I sell a fixed number of shares, receiving a variable amount of cash. At the start of each year, I choose the fixed number of shares to sell that year (based on the year-end value of my stocks and not subject to revision for a year at a time). The cash that comes in this way only approximates the cash I need to send IRS. So, the cash part of the IRA will grow or shrink a little; that doesn’t matter to me. I can’t find the reference now, but I read yesterday that one rich man was using the same method — selling a fixed number of shares at a fixed interval of time. Has anyone researched this method? It has one clear advantage: I do not attempt to time the market, which I know from sad experience would be beyond my ability.

Does DCA get championed when we encourage retirement plan contributors to keep up with their contributions? The “take from paycheck every two weeks” method is just going to demand that DCA is naturally done — so DCA is championed as a strategy for accumulating positions over time.

If the client has $100k right now and the market has a lot of buyers and is in an uptrend, then encouraging them to get participating faster is likely going to be the better strategy.

But the concept is mentioned in some many financial textbooks that it’s automatically extended to a lot of how investors think. Or… so it seems…

Michael, As usual a very interesting article. I would be interested if you combined this analysis with that done on the Shiller CAPE. Does DCA work better when the CAPE is high and worse when CAPE is low?

DCA would work better in time periods when the beginning of the period is a time when the CAPE is high and poised to come down. But I can’t help but think trying to use market forecasting methods to decide whether to use DCA is against (traditional) DCA logic. BTW, thanks to Michael for explaining that traditional DCA logic should be examined with actual market scenarios as opposed to the old examples that make teaching the concept easier.

Chad,

Agreed, all else being equal you’d expect DCA to work “better” in times of elevated CAPE, simply because forward market return expectations are reduced (which reduces the otherwise-problematic “upside bias” of markets that makes investors lose ‘on average’ by waiting to invest).

Given that high-valuation markets generally still have SOME positive return expectation, this probably still wouldn’t make DCA an “odds-on bet”, but it would definitely reduce the negative consequences, as well as increase the prospective “regret minimization” and risk management potential (given that high-CAPE environments have elevated risk).

– Michael

Well, from a block-bootstrap simulation I get different empirical evidence: less shortfall risk (both shortfall probability and expected probability), and just slightly less mean return. At least in an “average” situation, with reasonable fees. Of course, fees, time horizon, interest rates might have a strong impact on results, there is nothing conclusive. Anyway, here is the (short) paper: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2341773

Raffaele,

Isn’t that the exact same conclusion here? Slight reduction in average return, but it’s a reduced risk over the DCA time horizon, because you’re effectively taking an all-X portfolio and making it part-X-part-cash instead?

– Michael