Executive Summary

The modern broker-dealer structure was created in the aftermath of the Crash of 1929, as the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 set forth new rules and registration requirements for the financial intermediaries that either were dealers in securities from their own investment inventory, or brokered securities transactions for their customers (including in subsequent decades the distribution of securities products, like mutual funds).

Yet in the coming years, the broker-dealer business model is under threat from the looming rollout of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, which at best will likely reduce upfront commissions and drive a shift towards more levelized compensation for advisors, and some predict may eventually eliminate product commissions altogether.

Notably, a world without commissions is not necessarily the death knell for advisors, as the reality is that the non-commissioned RIA segment of advisors has already been experiencing the greatest growth in recent years, and even the majority of brokers have indicated that they think it is reasonable to be required to give advice in the best interests of their clients.

However, the ongoing evolutionary shift of “financial advisors” from securities product salespeople to actual advisors is creating an existential crisis for broker-dealers – after all, in a future fiduciary world where advisors are paid directly by their clients for advice, what is the purpose or need for a broker-dealer intermediary at all?

Which means in the long run, for broker-dealers to survive and thrive, they will be compelled to reinvent their business (and revenue) models altogether, to remain relevant in a world of financial advisors that rely on them not as financial intermediaries to facilitate the distribution and sale of third-party or proprietary securities products, but financial advisor support platforms that help to facilitate the success of cadvisors who are actually paid for their financial advice!

The Purpose And Origins Of The Modern Independent Broker-Dealer

The modern version of the broker-dealer can trace its roots to the aftermath of the Crash of 1929, out of which came the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 – the legislation that created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the rules for securities exchanges themselves and how they operate, and the rules and registration requirements of broker-dealers.

As the compound name implies, broker-dealers existed to fulfill two primary functions: to execute securities trades in their own account as a dealer, and to execute securities trades on behalf of customers as a broker. Notably, at this time a broker-dealer was typically attached directly to an investment bank responsible for assisting companies in raising (i.e., issuing) debt and equity capital. Thus, the process of raising funds in capital markets would involve an investment bank facilitating the issuance of stocks and bonds, which would then be held in the inventory of the broker-dealer, and stockbrokers would then be responsible for selling the newly-issued securities from the broker-dealer’s inventory to investors.

In the decades following the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the scope of broker-dealers expanded to include the sale and distribution of an ever-widening range of registered securities products – beyond just the stocks and bonds in the broker-dealer’s inventory, or brokering trades on the securities exchanges on behalf of customers. Most notably, this included the rise of the mutual fund, a securities product that could be brokered (i.e., sold) by the representatives of a broker-dealer. In this context, the mutual fund would pay the broker-dealer a selling concession for distributing its product, a portion of which the broker-dealer would then pass along as compensation to the broker in the form of a sales commission.

The growth of mutual funds (and to a lesser extent, other registered securities products) was so successful that by the 1970s and 1980s, there was enough money to be made by just brokering the sale of securities products and generating commissions, that the independent broker-dealer model arose and became popular. The key distinction of the independent broker-dealer was that it generally had no direct affiliation to an investment bank or investment company, and thus was not selling its own proprietary stocks, bonds, or other securities products. Instead, independent broker-dealers sold third-party securities, independent of the company itself.

In turn, the rise of the independent broker-dealer meant the role of the broker-dealer shifted, from dealing in securities in its inventory (to sell to customers) or packaging securities products (to sell to customers), to instead be responsible for the oversight of the sale of third-party securities products, including vetting/evaluating the products for sale, managing and overseeing the sales process (i.e., compliance oversight of brokers), and collecting and allocating the sales commissions that were paid.

As the registered representatives of broker-dealers – both independent and “captive” insurance or wirehouse broker-dealers – sought to add value to clients, they have increasingly offered a range of financial advice to consumers as well, to the point that most who work at such firms now are variously called “financial advisors” or “financial consultants”.

Notwithstanding this shift, though, functionally the reality is that the “advisors” who work for broker-dealers are still legally in the business of selling (proprietary or third-party) securities products and offering related brokerage services. In fact, the legal reality is that an “advisor” ceases to be a broker and must become a fiduciary investment adviser if their advice offering ever becomes more than just “solely incidental” to the sale of securities products and the delivery of brokerage services!

Are Broker-Dealers Irrelevant In A Fiduciary Future Of Advice?

The fundamental challenge for broker-dealers as financial advice moves inexorably towards a fiduciary future is that the broker-dealer operates primarily to facilitate the sale and distribution of securities products. They were never built as platforms specifically to support the delivery of financial advice, particularly in a world where advisors are compensated directly for their advice via fees and not with commissions paid by securities product providers for the sale of their products (or commissions paid directly by the broker-dealer for the sale of its own proprietary products). In other words, if the future of financial advisors is to get paid for advice (not the sale and distribution of securities products), what’s the relevance of a broker-dealer that exists primarily to facilitate the sale and distribution of securities products?

In this context, it’s not entirely surprising that broker-dealers have been overwhelmingly negative regarding the Department of Labor’s fiduciary proposal, and likewise why broker-dealer companies have been more negative about the fiduciary rule than brokers themselves. Because the reality is that brokers have been increasingly shifting towards delivering financial advice – and actually creating value with their advice – for years now, and many brokers already try to give advice in the interests of their clients (which is really the only way that advice can be given to really be advice!).

Which means in a fiduciary future, if forced to do so, brokers-as-financial-advisors can finally complete the transition to become true financial advisors who get paid for advice instead of product distribution, and those with an advice skillset can survive and thrive in a fiduciary future. Broker-dealers, on the other hand, risk becoming irrelevant in an advice-centric world. Which means fighting the DoL fiduciary rule has become an existential crisis of survival for many (or even most) broker-dealers.

Conversely, what this also means is that for broker-dealers to survive in a fiduciary future, broker-dealers must evolve themselves from being platforms that facilitate the sale and distribution of third-party or proprietary securities products, to ones that actually support the success of financial advisors who deliver advice (and are compensated primarily for the value of their advice).

How The Best Broker-Dealers Will Reinvent As Advisor Platforms To Survive And Thrive

So what exactly does it mean to create a platform to serve and support advisors, rather than merely operating a broker-dealer to facilitate brokers selling third-party or proprietary securities products? The starting point is to look at how the non-product-centric side of the advisory industry has already been evolving in recent years.

For instance, RIA custodians seek to create appealing platforms for RIAs primarily through technology that supports their advisors. All RIA custodians have some form of comprehensive advisor technology stack that their advisors rely upon to operate their businesses – through various combinations of proprietary solutions, ‘preferred vendors’ with deep integrations, and/or creating an open architecture framework into which technology solutions can be plugged in. In a world where so much of the raw custody business has been brutally commoditized, custodian platforms increasingly differentiate on the basis of their technology.

Notably, though, the RIA advisor support ecosystem goes further than just how RIA custodians support their advisors. An interesting phenomenon of the advice industry, with its relationship-based recurring revenue business models, is that advice-based firms have grown far larger than the collection-of-silo’ed-brokers seen in the typical broker-dealer firm. This has led to everything from mega-RIAs that become so large, they themselves become a form of “advisor platform”, and those platforms are then grown via mergers and acquisitions, “tuck-in” deals, or even RIAs themselves offering third-party platform services to other advisors.

In this context, the function of the “advisor platform” is to help facilitate as much of the back-office operational functions, and even “mid-office” functions (e.g., investment and increasingly financial planning analysis) as possible, so that the advisors themselves can spend as much time as possible performing their highest and best use: interacting directly with clients, giving advice, and delivering value.

Accordingly, the “advisor platform” of the future might include not only technology solutions, but centralized back-office support (including operations and administrative support), centralized financial planning expertise (from an “Advanced Markets” sales support team to an “Advanced Planning” advice support team) and financial planning staff support (why should advisors need their own paraplanners when a central advisor platform can provide them on shared/pooled basis?), and even a Due Diligence department (not to vet products to be sold, but to meet the even higher burden of vetting products that will be recommended by fiduciary advisors). And of course, compliance – in a fiduciary context, not FINRA-style product sales oversight! – is also a highly relevant advisor platform function that benefits from scale.

Reinventing The Broker-Dealer Revenue Model - From Grid Payouts To Flat-Fee TFPP?

Ultimately, the greatest threat for broker-dealers may not be the fact that they must reinvent their service model to be relevant for advisors who get paid for advice (rather than brokers who get paid to distribute product) – it’s the fact that broker-dealers may soon be forced to reinvent their entire revenue model as well.

After all, if a fiduciary rule drives advisors away from product distribution and towards getting paid for advice itself, such that broker-dealers can no longer rely on their current role as an intermediary in the world of financial services product distribution, then broker-dealers will lose ‘access’ to everything from commissions with their revenue-sharing and override payment structures, to the “shelf space” agreements from product companies looking for distribution.

Perhaps some of this revenue will ironically be made up by financial services product companies that go from paying for distribution opportunities through revenue-sharing and shelf space agreements, to those product providers offering to sponsor advisor events and conferences to get visibility with fiduciary advisors and have their products considered as potential recommendations. (Again, when looking at parallels in the medical industry, drug companies continue to be heavy sponsors of conferences for doctors to build awareness of their products with the doctors who function as gatekeepers for their patients, even if the drug companies cannot pay commissions to doctors to use their drugs.)

To some extent, the transition towards fiduciary advice may simply mean a push away from ‘traditional’ upfront commissions, and towards levelized commissions akin to ongoing AUM fees. In the long run, this may not necessarily be problematic for broker-dealers. In fact, traditionally businesses with recurring revenue have better valuations, and in recent years the broker-dealers with more fee-based revenue have already commanded higher valuations than their purely-commission-based brethren.

However, just as financial advisors themselves often struggle with the transition from upfront commissions to levelized AUM fees – for instance, going from a 5% upfront commission to a 1% AUM may be more profitable in the long run (6+ years), but can cause a cash flow squeeze in the short term (getting paid 1% in year 1 instead of 5%!)– so too will broker-dealers face a potentially challenging revenue transition in the coming years if the Department of Labor fiduciary rule squeezes down the size of up-front commissions.

Perhaps even more problematic, though, is the prospective rise of non-commission or even non-AUM-fee advisor revenue models, and the question of where broker-dealers fit (or not) in that advice-centric advisor business model of the future. Whether it’s annual or monthly retainer fees, or even new forms of net-worth-and-income-based fee structures, how can broker-dealers get paid in a process where compensation typically goes directly from the client to the advisor (and not via the broker-dealer middle-man), and what is the reasonable amount for a broker-dealer-turned-“financial advisor platform” to be paid?

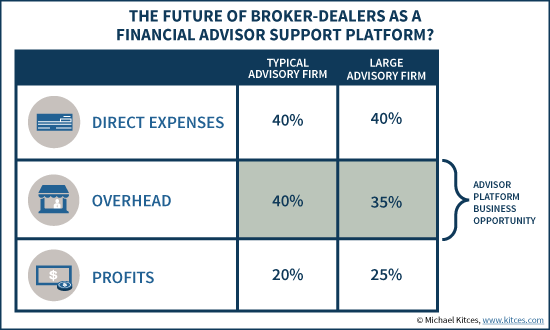

Industry benchmarking studies for independent advice-centric advisors show that the “typical” profit-and-loss statement for an advisory firm follows a roughly 40%/40%/20% split – where 40% is allocable to “Direct Expenses” (payments to advisors to provide advice), 40% goes to overhead, and 20% remains as a profit margin for the advisory firm. “Larger” advisory firms (which might still “only” be $1B of AUM and $10M of revenue, a fraction of the size of mid-to-large sized broker-dealers), which enjoy at least some economies of scale in their operations, may run a 40%/35%/25% split. Which means a fully scaled “advisor platform” that covers virtually all of the back- and middle-office overhead functions of an advisory firm could conceivably have a crack at perhaps 30% of an advisory firm’s revenue (given that a few expenses, like office space/rent, won’t likely be subsumed by the advisory firm platform).

In other words, the advisor platform of the future could potentially be relevant for as much as 30% of an advisor’s revenue, by providing all of the staffing, support, and other services necessary to allow an advice-centric advisor to spend as much time as possible actually giving advice to clients. For advisors who operate an on AUM basis, this might mean the broker-dealer advisor platform provides the investment management platform (as well), collects client fees, and remits the advisor’s (70%) share. And in point of fact, there are some advisor platforms that already do exactly this in a non-broker-dealer format, from BAM Alliance to Dynasty Financial Partners and Hightower Advisors.

For firms that support advisors doing retainer and other fees, this may eventually mean broker-dealer advisor platforms offering fee collection solutions for their advisors, again to collect fees from clients, keep their 30% “platform fee”, and then remit the 70% share to their advisors. Alternatively, some broker-dealers may simply establish and assess standalone “platform” fees – which could be basis points, or for non-AUM advisors simply a flat monthly platform fee, which the advisor pays on an ongoing basis to have access to all the technology, tools, and services of the advisor platform. Platforms would then differentiate on the basis of how “turn-key” they are to support certain types of advisors running particular business models or serving certain specialized clientele (the rise of the Turnkey Financial Planning Platform, or TFPP!).

The bottom line, though, is simply this: broker-dealers are facing a form of existential crisis, as the evolution of financial advisors from selling securities products to actually getting paid for advice raises the fundamental question of why it’s necessary at all for an advisor to affiliate with a broker-dealer intermediary to facilitate the distribution of those products. This existential threat to broker-dealers will only be accelerated by the rollout of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, as the potential shift away from upfront commissions – and possibly away from commissions altogether – will open the door to an explosion of non-product-distribution-based advisor support platforms. And while some broker-dealers may be able to make the “shift” from product intermediary to a bona fide advisor support platform, it seems increasingly likely that many simply aren’t positioned to survive (much less thrive) in an advice-centric future.

So what do you think? Will broker-dealers remain relevant in a less-product-centric fiduciary advice future? What services would broker-dealers need to provide to still be appealing as a platform for advisors? Will broker-dealers be disrupted by third-party advisor support platforms from BAM Alliance to Dynasty Financial to XY Planning Network?