Executive Summary

The conventional view of “whole life” and other forms of “permanent” insurance coverage is that the policies are designed to last for your entire life, however long you may live. As long as you keep paying the premiums, you can keep your coverage, until it pays out as a tax-free death benefit.

However, the reality is that the underlying structure of permanent insurance, and the key characteristic that makes it affordable to have coverage – even in the later years of life – is that a “permanent” insurance policy actually has an ultimate maturity date, such as age 100. Which means if you live beyond that point, the policy “matures” and pays out its face value!

And the problem with outliving life insurance is not merely that the policy matures and pays out its benefit, but the fact that it was paid while alive – and not as an actual death benefit – meaning the payout is a taxable gain to the policyowner! In other words, outliving the life insurance maturity date not only marks the end of life insurance coverage itself, but a taxable event!

Fortunately, policies issued in the past 10 years or so primarily use the newest 2001 CSO mortality tables, which were extended to a maximum life span of age 121, to reduce the risk of the insured outliving the end of life insurance mortality tables. However, most existing permanent life insurance was issued under “old” mortality tables with a maximum age of 100 (or even age 96), which means most permanent life insurance owners still have to contend with the possibility that they can actually outlive their life insurance… and face the tax consequences that come with it!

Origins Of Permanent Life Insurance With Cash Value

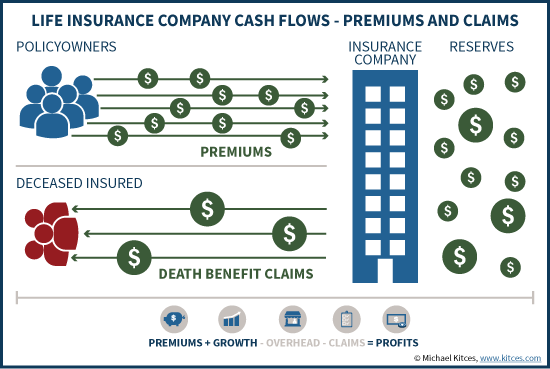

A life insurance company functions by collecting premiums from those who are insured, and paying out claims for the small subset of those insured individuals who die in any particular year. And the fact that the insurance company “knows” – thanks to the law of large numbers – about how many people are likely to die in any particular year makes it possible for the insurance company to set an appropriate premium. Those premiums are then used to ensure the company has sufficient capital to both pay claims from year to year, (although ultimately the insurance company must take in slightly more than it pays out, to also cover cover the overhead and operating expenses of the insurance company, plus some margin for the company to earn a profit).

While this works well enough for term insurance, an additional complicating factor arises in the case of “permanent” insurance, that is meant to continue “permanently” for however long the insured may live. In the case of permanent insurance, it becomes impractical to just charge an age-appropriate premium for the policy every year, because the coverage would become prohibitively expensive in the later years as our mortality rate rises.

To resolve the dilemma, permanent insurance policies are typically structured as “endowment” policies that are meant to mature at the face value of the policy at an advanced age – e.g., age 100. Premiums are set at a level where their contributions, plus ongoing growth, will allow the policy to pay out its stated “maturity value” at the end of the time horizon.

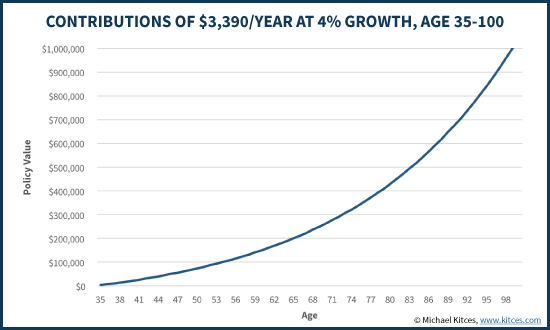

For instance, a 35-year-old might buy a policy with a $1,000,000 face amount, which means the premiums are set at a level that would produce $1,000,000 at age 100. Assuming a conservative 4% growth rate (as insurance companies are generally bond investors, to ensure that they’ll have the cash when they need it!), this would require a premium of $3,390 per year.

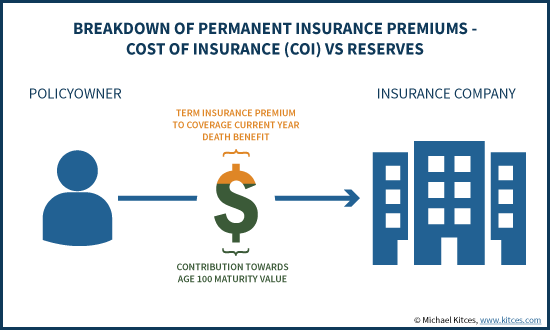

Of course, the caveat is that in addition to charging enough of a premium to have an “excess” to build the value of the policy to $1,000,000 at age 100, the insurance company must charge an additional premium to reflect the fact that it is also on the hook for $1,000,000 of death benefit if the individual dies before age 100. In other words, it must charge an extra amount to cover the equivalent of what the insured would have also paid for term insurance that year, “just in case” the insured actually happens to die in the first year, rather than surviving all the way to age 100! Thus, the actual premium for a permanent insurance policy for a 35-year-old will be something more than “just” $3,390/year noted above – perhaps $3,500 to $4,000/year instead.

Notably, though, this means that permanent insurance policies are technically charging a “premium” that is far more than is necessary to just cover the actual cost to purchase a death benefit for the year in question. In fact, this is why permanent insurance is far more “expensive” in premiums than term insurance. Because the premium must also provide enough of a contribution to cover not only the potential death benefit, but create “excess” funds, which can then be invested to generate the necessary returns to ensure the policy will endow at its face value at age 100!

Why An Endowment Policy Makes Permanent Insurance Coverage Possible

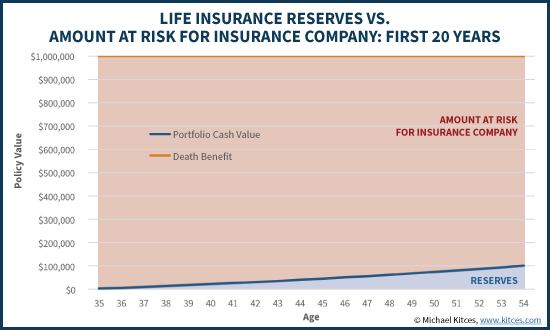

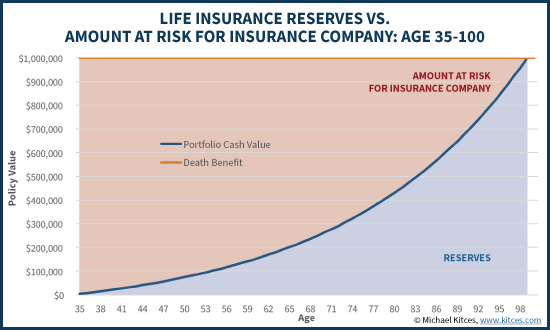

The reason that formulating a permanent life insurance policy to endow at age 100 solves the challenge of prohibitively expensive life insurance premiums in the later years is that technically, the insurance company is providing less and less actual insurance coverage in the later years.

After all, the typical permanent insurance policy might stipulate that it will pay $1,000,000 as a death benefit if the insured passes away, or $1,000,000 as a maturity benefit if the insured lives to age 100. However, since the insurance company is collecting “extra” premiums to invest, in order to have the cash available to pay out $1,000,000 at age 100 even if the insured doesn’t die, that means as the years go by the insurance company isn’t actually at risk for nearly as much life insurance protection.

For instance, revisiting the earlier scenario, consider for a moment what happens if the insured makes ongoing premium payments – to cover both the annual insurance death benefit, and to build up the reserves to have the policy endow at $1,000,000 at age 100 – and then passes away after only 20 years. Since the policy has a $1,000,000 death benefit, the insurance company is committed to paying out that much upon death. However, by the end of the 20th year, the insurance company would have already built a reserve of about $101,000 for the policy (which the policyowner would see as the “cash value” of the policy). As a result, paying out the $1,000,000 death benefit actually requires the insurance company to pay only $899,000 out of its own pocket, on top of the $101,000 cash value reserve that was already associated with the policy.

The fact that the insurance company had only $899,000 “at risk” in the form of a death benefit it might have to pay – since the other $101,000 is already set aside as cash value reserves – means that the implicit cost of the death benefit in the 20th year is based only on $899,000, and not the full $1,000,000. This is important, because it means that while the cost of insurance (for every $1,000 of potential death benefit) is going up every year (given that our mortality rate rises every year we get older), the amount of insurance exposure decreases.

Thus, then, in the logical extreme, for an individual who actually lives all the way to age 100, the true amount at risk for the insurance company – the amount of death benefit that would be paid over and above the existing cash reserves – is quite small in the final years. Accordingly, even though the cost of any insurance coverage can be quite expensive for those at an advanced age – e.g., in their 90s –the insurance company is only actually providing (and the insured policyowner is only paying) for a very small amount of true death benefit protection.

How Permanent Life Insurance Can Expire At Age 100

The virtue of the endow-at-age-100 structure of “permanent” life insurance is that it provides a means for coverage to remain in place for life, without having the cost of insurance charges become prohibitively expensive at the end. As the policy approaches its endowment date, the actual amount of true insurance coverage (over and above the cash value reserves) shrinks, which makes the overall cost manageable.

However, this standard approach of life insurance raises one significant problem, which is becoming of increasing concern in today’s modern world: if the insured isn’t actually deceased by age 100, the policy matures and pays out its face value! In other words, “permanent” life insurance can actually expire!

From the general investment perspective, this isn’t necessarily bad news. The policyowner will have still gotten the full implied return on the policy over the time period, and earned the assumed/guaranteed growth rate that was applied to the excess premiums for all those years.

The problem with a life insurance policy that matures is from a tax perspective. Because while the standard rule for life insurance is that a death benefit is tax free under IRC Section 101, the tax code explicitly states that the tax-free treatment only applies “if such amounts are paid by reason of the death of the insured.”

Which means if a life insurance policy’s face value is paid out because it “matured” – the insured actually lived to the end of the time horizon – the proceeds are fully taxable as ordinary income (to the extent the final proceeds are greater than the cost basis of the policy based on the cumulative premiums paid over the years).

Which means there is a significant tax incentive for a policyowner to not actually live until the policy itself matures! Otherwise, what happens when the life insurance expires is the same as what happens when a cash value policy is sold as a life settlement or surrendered: it triggers a taxable gain! Or viewed another way, being able to keep the policy as life insurance – and have it pay out as a life insurance death benefit – is the difference of whether a lifetime’s worth of gains (literally, a lifetime’s worth!) are fully taxable, or paid out tax-free!

Extending The End Of Life Insurance Beyond Age 100

Notably, the life insurance maturity age of 100 exists primarily because the mortality tables used for life insurance during most of the 20th century (the Commissioners’ Standard Ordinary [CSO] tables of 1941, 1958, and 1980) were all based on a maximum “terminal” age of 100 (i.e., there literally were no life expectancy tables past age 100, as it was implicitly assumed ‘everyone’ would be dead at that point!).

And with older life insurance policies (issued before the 1941 CSO table), the situation was/is even worse; those policies rely on the original mortality tables first widely adopted by U.S. life insurance companies in the 1860s – the American Experience mortality table – which had a maximum age of 96 (which means those policies will mature at age 96). In fact, as health improved throughout the 1900s, there were even stories that began to emerge of those who “outlived” their age-96 life insurance mortality tables.

Recognizing this emerging problem, the update to the CSO tables in 2001 expanded the mortality tables to extend the end of life insurance all the way out to age 121. As a result, most new permanent life insurance policies today are issued with a maturity age of 121.

Notably, though, even in the case of the new CSO 2001 tables, there is a complication to the “possibility” that someone outlives their life insurance past age 100 – while the mortality tables now extend to age 121, IRC Section 7702(e)(1)(B) defines a “life insurance contract” for tax purposes as one with a maturity date “no later than the day on which the insured attains age 100”!

Several years ago, the IRS sought comments about how best to “remedy” this issue in IRS Notice 2009-47, and subsequently issued its decision as Revenue Procedure 2010-28, which stipulated that as long as an insurance policy accumulated its cash value as though it was going to mature at age 100, it could be continued past that age (as late as age 121) without being required to pay out its (taxable) maturity value. In other words, the policy must still be structured such that its cash value is expected to equal its death benefit face value at age 100 (or if there’s a shortfall, the death benefit may be reduced to equal the then-available cash value at that time), and from that point forward the insurance policy would simply continue to earn its cash value return (but would no longer have any death benefit amount at risk).

What If An Insured Outlives The Old CSO Mortality Tables?

In theory, the new 2001 CSO tables resolve the issue of “outliving” life insurance – or at least, Jeanne Louise Calment only been one known person in recorded history to have lived past age 121, so the odds are very good age 121 will be sufficient for most to avoid the end of life insurance mortality tables, unless we have some major medical breakthroughs sometime soon!

However, “older” existing policies – i.e., every permanent life insurance policy that’s been around for 10+ years and was issued before the 2001 CSO tables took effect from 2004 to 2006 – continue to still use the age-100 maximum age from the prior CSO tables (or even the age 96 threshold from the old American Experience mortality tables!).

For all those prior policies, a life insurance policy remains something that can actually be outlived, where the insured reaches the end of life insurance mortality tables and the policy matures at the maximum age of 100 (or 96)… paying out as a taxable maturity value. And arguably, as medical advances and health improvements continue, this may become an increasingly common challenge for older clients. Of course, a policyowner could try to avoid this consequence by surrendering the policy earlier, but that only accelerates the tax consequence (in addition to undermining the economic benefits of holding life insurance coverage until death).

Notably, there is still some debate about whether a policyowner who lives to see his/her life insurance policy “mature” at age 100 could choose to keep the funds invested with the insurance company, and not be forced to face the tax consequences (presuming he/she didn’t actually need the money anyway). The general tax principle of “constructive receipt” suggests that the funds should be fully taxable once the policy matures and the policyowner has unfettered access to the policy’s maturity value. In fact, the IRS even raised the potential issue in the aforementioned IRS Notice 2009-47.

In response, the American Council of Life Insurers (ACLI) made the case in a comment letter to the IRS that constructive receipt should not apply, though leading insurance commentators like Joseph Belth suggest that this remains an ongoing issue. Ironically, IRC Section 72(h) actually does provide that a contract which pays a lump sum can avoid constructive receipt if it offers the option to pay an annuity instead (and the policyowner exercises that option within 60 days)… except, of course, an annuity isn’t necessarily a very appealing purchase for someone who just turned 100!

Which means for the time being, those who own life insurance and are approaching the maturity age of their life insurance policy really do face the potentially “taxing” problem of outliving their insurance coverage, and being impacted by the resulting taxable event of receiving the policy’s proceeds as a living distribution!

Excellent article, but please ho easy on the exclamation marks!

BTW 121 may still be too short for someone who is in his or her 30s! The potential for medical technology to extend the lifespan another 15% over 80 years is definitely there! It’s the equivalent of using the “impossible” 96 years all over again! Permanent should not mature, ever!

Sorry, I think the exclamation marks are hard wired into my keyboard! 🙂

– Michael

So at age 99 you do a max loan on the policy and drain as much cash as possible?

Josh,

No, that doesn’t help. The policy matures at age 100 anyway (where applicable).

So the policy will mature, the maturity value will be used to repay the loan, you’ll get the net proceeds, and you’ll still be taxed for the entire maturity value.

All you’d accomplish with this is racking up a year’s worth of unnecessary loan interest.

– Michael

Of course. The maturity value being taxable is confusing. Good article. Thanks

It’s just like any investment that matures and liquidates.

Think of it like this:

You bought a house. You’re required to liquidate it at age 100 by contract, and pay taxes on the gains.

You can take out a mortgage loan when you’re 99 using the house as collateral, but that doesn’t change the fact that you still own the house, have a gain, and are required to sell it in a taxable event at age 100.

A life insurance loan is really just a personal loan from an insurance company, using life insurance cash value as the collateral. That doesn’t change the tax consequences of liquidating the collateral in a taxable event.

– Michael

So it’s a pillow to the face at 99.5?

Excellent post!

Thanks!

– Michael

Couldn’t the insurance companies create a product that you could do a 1035 exchange into that would give you the extra years? It could be structured with almost no mortality fee (the insurance part would be very small) to basically extend a permanent policy? Throw a maximum age in there of 90 or 95 to force healthy older adults to buy it soon enough.

Conceivably perhaps. It would just be brutally difficult to underwrite and highly sensitive to underwriting mistakes given the mortality at that age.

Probably more practical to try to do the swap in “just” your 70s or 80s, where it’s easier to underwrite and therefore pricing can be more stable?

Just my gut guess as to why we don’t actually see many/any policies to do this kinds of exchanges in your 90s…

– Michael

A 1035 exchange with zero underwriting to avoid the taxing issue of unanticipated gain would seen reasonable and justified in these instances.

Yes. Just fix the tax problem and charge a small fee for it. Minimal risk underwriting.

I did address this issue with a top carrier a number of years ago and their explanation was that so long as they-the insurance company maintained possession of the death proceeds until the Insureds death, the Service would not tax the proceeds.

I do mention this issue to any number of my clients, explaining to them that when their policy cash values equal the policy death benefit at their age 100, they will in fact, be well endowed.

I have only a smattering of insurance knowledge, but is it not the case that the taxable amount on collapse of a policy (and I presume on payout at living age 100) is the net amount of the insurance payout LESS the accumulated yearly insurance costs?

It was my understanding that the offset was not the sum of hte premiums paid, but rather the effective yearly term insurance. So anyone not-dying at age 100 will have had humungous yearly insurance costs deducted for the past decade or two. Resulting in little being taxed??????

What happens when a permanent life policy that is owned by a irrevocable insurance trust reaches maturity? Would the trust then have the same taxable event? Is there standard language included in insurance trusts documents to cover this possibility?

With a traditional whole life policy that reaches maturity

at age 100, if the insured dies at age 101 will they receive the full face

value of the policy or the cash value account?