Executive Summary

When a beneficiary inherits property from a decedent, the asset receives a step-up in basis to its value on the date of death – which is both a tax perk for inheritors, and a form of tax simplification (as beneficiaries otherwise may not know what the decedent’s original cost basis was anyway).

However, with hard-to-value assets, there may be a disagreement between the valuation for estate tax purposes, and the value used by the beneficiary for cost basis reporting. After all, the estate prefers a small value (to minimize estate taxes) while the beneficiary ideally wants the highest possible value reported (to get a higher basis step up). And in the past, it was even possible for the executor and beneficiary to report different amounts, each to their own benefit (and the detriment of the IRS!).

To close this perceived “loophole”, in 2015 Congress created the new IRC Section 1014(f) that requires beneficiaries to use a date-of-death valuation for cost basis purposes that is no larger than the amount reported on the estate tax return, curbing the abuse. In addition, Congress also established the new IRC Section 6035, which requires executors to file a new Form 8971 to notify the IRS who the beneficiaries are, along with a Schedule A that informs both the IRS and the beneficiaries what their inherited cost basis will be.

The good news of the new reporting form is that it should actually ease the burden for beneficiaries who need to determine cost basis for their inherited assets. However, the requirement is a new burden for executors, who may struggle to follow the 30-days-after-Form-706 deadline for filing the new Form 8971 and supporting Schedule A, especially in situations where it takes a long time to identify all the beneficiaries and determine which property will be distributed to them. In fact, ironically the rules have been so complex to roll out, that the IRS has had to repeatedly delay its implementation as well, though the new Form 8971 reporting requirements are now scheduled to take effect by June 30 of 2016, and will apply retroactively back to any estate tax returns filed since last July 31 of 2015!

Inconsistent Basis Reporting By Executors And Beneficiaries Eligible For Step-Up

The standard rule for beneficiaries under IRC Section 1014 is that the cost basis of any inherited property will be equal to its value on the date that the decedent passed away. This “step-up in basis” rule can be a significant income tax benefit for beneficiaries – allowing them to avoid any embedded capital gains on the property that were unrealized at the death of the prior owner. For instance, if the original owner purchased an investment for $40,000 and it appreciated to $100,000, and was bequeathed at that value at the death, the beneficiary would inherit the property at a $100,000 cost basis and the $60,000 gain would vanish forever.

From a practical perspective, the step-up in basis rule also simplifies capital gains reporting for beneficiaries, who can just use the date-of-death value and don’t need to go back and figure out what the property’s original cost basis was (which would be difficult or impossible given that the original owner is no longer alive!).

In most cases, determining what the cost basis of the inherited property will be is fairly straightforward – the executor determines the value, and reports it on the Form 706 estate tax return. However, technically the fact that the estate reported a certain value for the property at the date of death is not necessarily binding on the beneficiary, who might in some cases reasonably believe that the executor’s estimate of the value was incorrect. Under Revenue Ruling 54-97, the value reported on the estate tax return is merely a presumptive value, and a beneficiary may rebut that valuation and claim a different once instead.

Notably, such conflicts about the desired valuation can be quite common, given the opposing tax views of an estate executor and a beneficiary. In cases where an estate is large enough to be subject to estate taxes, the executor wants the reported values to be as low as possible, to minimize any Federal or state estate taxes. However, the beneficiary wants the reported values to be as high as possible, to increase the value to which basis will be stepped up.

Unfortunately, though, in the case of high-net-worth individuals with illiquid assets, there really can be some uncertainty about the “proper” valuation of inherited property, and the fact that the valuations could be “reasonably” different creates the potential for tax abuse. For instance, if a wealthy inheritor has a highly illiquid business, an executor might legitimately get a valuation of $100M for the business from one expert, and the beneficiary might legitimately get a valuation of $110M from another expert, allowing the estate to minimize estate taxes with one valuation even as the beneficiary maximizes step-up in basis with another. In the case of Janis v. Commission of Internal Revenue, a dispute of this nature did occur, about the "proper" valuation of hard-to-value artwork (where the estate claimed a lower value for estate tax purposes and the beneficiaries tried to claim a higher value for the purpose of determining their step-up in basis.

To crack down on this perceived estate planning “loophole”, the Treasury Greenbook for the President’s FY2010 budget proposed a crackdown that would require beneficiaries inheriting property to use a valuation no greater than what was claimed on the estate tax return. In other words, if the executor claimed a “low” valuation for estate tax purposes, the beneficiary would be bound to that amount for determining inherited basis as well; alternatively, if the beneficiary wanted a higher basis to minimize capital gains taxes, the executor would have to report a higher value in the estate (potentially causing a higher estate tax bill in the process).

2015 Highway Bill Requires Consistent Cost Basis Reporting Between Estates And Beneficiaries

As is often the case, proposed crackdowns in the President’s budget don’t necessarily become standalone tax legislation, but are often used as a revenue offset in other legislation. And ultimately, this was exactly what happened with the proposal to require consistent valuations between estates and beneficiaries – after being re-proposed repeatedly in the President’s budget, the rule was finally adopted in Section 2004 of the Surface Transportation and Veterans Health Care Choice Improvement Act of 2015.

The final rule introduced two new requirements to facilitate “consistent” valuations for cost basis reporting by inheritors.

The first was the creation of the new IRC Section 1014(f), which explicitly requires that the basis in the hands of the beneficiary cannot exceed the final valuation of the property used to the determine estate tax liability in the first place. (In theory the beneficiary could still use a lower amount, though in practice this wouldn’t be desirable except perhaps in a situation where there’s a concern the executor’s valuation is so wrong the beneficiary could be subject to penalties for using it, too.)

Second, the Highway bill created IRC Section 6035, which establishes a new requirement for the executor of the estate to file an information form with the IRS (and a copy provided to beneficiaries) reporting the valuation of the assets in the estate for the purposes of cost basis reporting (so the IRS can ensure that the beneficiaries report the cost bases properly in the future).

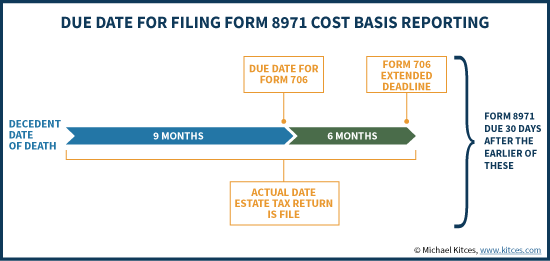

This new IRS Form 8971 identifying the inherited property and its date of death valuation must be delivered by the earlier of 30 days after the estate tax return is filed, or 30 days after the estate tax return was due to be filed (if it wasn’t actually filed in a timely manner). On the other hand, this new reporting requirement only applies if an estate tax return was required to be filed in the first place (and thus, estates below the filing threshold are not subject to the new reporting rule).

Notably, the new cost basis consistency requirement only applies to property that actually caused an increase in estate taxes due to its inclusion in the estate, although any estates that file an estate tax return must at least file a Form 8971 (albeit just to note that the inherited property is not subject to the basis consistency rules). It's only estates that are below the estate tax filing threshold altogether that avoid the filing requirement altogether. In situations where there is a required to file but no estate tax due - e.g., because of the charitable or marital deductions - Form 8971 is required, but the inherited property could theoretically have different valuations between the estate tax return and the beneficiary.

On the other hand, the elimination of the Form 8971 filing requirement for estates that don't have a filing requirement at all does effectively ensures that estates not required to file an estate tax return also won’t be subject to the basis consistency rule anyway. Estates that are subject to estate taxes on the other hand, must both be subject to the basis consistency rule and file the estate tax return and supporting basis reporting information forms.

Executors who fail to file the information reporting forms (if required) will be subject to a penalty of $260 per information return (which could be significant if there are many beneficiaries). The penalty is reduced to $50 per information return if the statements are provided within 30 days after the due date. Notably, though, an intentional disregard of the filing requirements is subject to far greater penalties.

Immediate Filing And Delayed Effective Dates For New IRS Form 8971

When the Highway legislation (H.R. 3236) was signed into law, the new reporting requirements for IRS Form 8971 became effective immediately for any/all estate tax returns filed after the July 31, 2015 enactment. Of course, the caveat was that while the requirement took effect immediately, the IRS hadn’t even designed Form 8971 yet, much less issued any supporting guidance about how to complete it.

Accordingly, IRS Notice 2015-57 was issued just a few weeks after the law was passed, and delayed the reporting requirement – any estate tax returns filed after July 31, 2015 were still subject to the Form 8971 filing rules, but could have until as late as February 29 of 2016 to actually file (allowing time for the IRS to create and issue instructions for the requisite paperwork).

And after issuing a draft version of the form and supporting instructions in early January, the Service released the “final” version of Form 8971 and the supporting instructions on January 29th. However, due to lingering questions about how to execute the forms, the IRS issued Notice 2016-19 on February 11th, further extending the Form 8971 extended due date again to March 31st, and then subsequently issued IRS Notice 2016-27 extending the first filing deadline again, to June 30th.

Thus, in today's environment, any estate tax returns that were filed after July 31 of 2015 will need to file a new Form 8971, but will have until the later of 30 days after the Form 706 was filed (under the standard rules), or until June 30th of 2016 if later (the extension for the new rules).

Filing Requirements For IRS Form 8971 And Schedule A To Report Step-Up In Basis

Form 8971 is only required to be filed in situations where a Federal estate tax return is otherwise required in the first place. As a result, the new rules will generally only apply to those with a gross estate above $5.45M in 2016, or noncitizen nonresidents with an estate in excess of $60,000. And notably, under Proposed Treasury Regulation 1.6035-1(a)(2) issued in early March of 2016, a Form 8971 is not required to be filed in situations where the Federal estate tax return was filed solely to claim portability of the deceased spouse's unused estate tax exemption.

Under the final version of the form itself, executors will be required to report in Part I both the decedent and executor’s names, and in Part II a list of all beneficiaries and their tax ID numbers (Social Security numbers for individuals, or TINs for trusts). This first page of the form goes only to the IRS (as it would be a potential privacy breach to share with other beneficiaries).

Then, for each beneficiary, the executor must prepare a copy of Form 8971 Schedule A, which details for each beneficiary what property was inherited, the valuation amount (and date of valuation), and whether the asset increases the estate tax liability (such that it would be subject to cost basis consistency rules under IRC Section 1014(f)). If the estate’s property has not been fully distributed yet, then each beneficiary’s Schedule A must list any property that could be used to satisfy the beneficiary’s interest (to ensure the beneficiary and IRS both have the right information for whatever property actually is inherited).

Notably, the rules stipulate that each beneficiary should receive their own Schedule A, in addition to a copy of all Schedule A forms being submitted to the IRS. Furthermore, in the Proposed Treasury Regulation 1.6035-1(f), if the beneficiary subsequently transfers property to another "related transferee" (e.g., a spouse, ancestor, descendant, or sibling, as defined in IRC Section 2704(c)(2)), a supplemental Form 8971 and Schedule A must be re-filed within 30 days of that transfer; notably, this could require a new Form 8971 filing years or even decades after the property was originally inherited, if it was held throughout and re-bequeathed later!

Certain property that is not conducive to valuation, or not eligible for step-up in basis, is excluded from the requirement to be listed on Schedule A. Under Proposed Treasury Regulation 1.6035-1(b), this includes cash, items of tangible personal property worth less than $3,000 (for which an appraisal isn't otherwise required), property sold by the estate itself (and therefore not bequeathed to a beneficiary for a step-up in basis anyway), and any assets that are income in respect of a decedent (also not eligible for a step-up in basis anyway).

Planning Issues And Complications Of The New IRS Form 8971 Requirements

Because the new IRS Form 8971 applies only to those who are otherwise required to file a Federal estate tax return in the first place (i.e., those with estates over $5.45M in 2016), arguably the scope of the new rules is fairly limited. Nonetheless, the implications are significant, because those who are subject to the rules often have the most complex estates in the first place.

The fact that the new reporting forms aren’t due until after the Form 706 does “ensure” that there will be proper valuations for all the assets in the estate, as that’s required for the estate tax return itself. Whatever values are determined for the estate will generally now simply flow through to Form 8971.

The caveat, however, is that while the valuations on the estate may be known by the time the estate tax return is being filed, the beneficiaries may not all be known, nor may it necessarily be clear yet who is getting what from the estate.

For instance, if the decedent’s Will or revocable living trust includes some hard-to-reach beneficiaries, or perhaps a distant “takers of last resort” clause that distributes assets widely to distant family members, the executor may still be trying to find all the beneficiaries within 30 days after the estate tax return is filed. And it’s not entirely clear how the executor should handle the situation.

Similarly, even if all the beneficiaries are known, it may not be clear what assets are going to be used to satisfy each bequest. If the specific property hasn’t been identified and distributed by the time Form 8971 is due, the executor is required to report any/all property that could be used for the bequest. But this potentially turns a very private estate manner into something more public, as if it’s not clear what property will be used for which bequest, the executor will effectively be compelled to disclose all assets in the estate to all beneficiaries on their respective Schedule A forms! And if the assets distributed end out being different yet again, the executor is further required to file a supplemental Schedule A within 30 days of that change, too.

In practice, the new Form 8971 basis reporting rules will likely lead executors for most high-net-worth estates to wait as long as possible to file the Form 706 estate tax return in the first place… since filing the 706 earlier just forces the basis reporting to be done earlier as well (since the latter must be submitted within 30 days of the former). Of course, this delay tactic for filing the Form 706 still only provides up to 9 months after the date of death (plus another 6 months on extension), after which the estate tax return must be filed (and the basis reporting form within 1 month thereafter).

On the plus side, the fact that beneficiaries going forward will receive a Form 8971 Schedule A detailing the cost basis of all inherited property should make it easier for the inheritors, who no longer will need to look up date-of-death values themselves. Instead, the information will all be ‘conveniently’ reported. The fact that Schedule A is only required to be filed in situations where there may be a Federal estate tax will also be a helpful indicator to beneficiaries about which assets may also be eligible for a IRC Section 691(c) income in respect of a decedent (IRD) deduction as well (although technically under Proposed Treasury Regulation 1.6035-1(b), IRD assets themselves are not required to be reported on Form 8971).

More broadly, though, many commentators still debate whether the administrative convenience to beneficiaries is really worth the hassle (and administrative costs) that will be imposed on executors, especially when the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that this change will raise “only” $1.5B of tax revenue for the Federal government (which amounts to barely 0.005% of the annual Federal budget) and the current scope of the estate tax is fairly narrow (with only about 2 of every 1,000 estates facing any Federal estate tax at all). The requirement under the Proposed Regulations in March of 2016, which stipulates that re-bequeathed property to a related transferee is subject to another Form 8971 reporting requirement (even if it occurs years or decades later), has also become a highly controversial provision, given the potential reporting burden (and significant penalties for noncompliance).

Still, the new consistent basis reporting rules, along with the IRC Section 6035 requirement for executors to provide an informational statement of cost basis to the IRS and beneficiaries, is the law of the land now. So at best, resolving any remaining hassles in the timing and execution of IRS Form 8971 and its supporting Schedule A will be left to the administrative guidance of the IRS and Treasury in the coming months and years.

So what do you think? Do you have clients who will be impacted by the new cost basis reporting and valuation rules? Do you think this is more of a "plus" for beneficiaries who will receive convenient step up in basis reporting details, or a burden for executors who must comply with the new rules?