Executive Summary

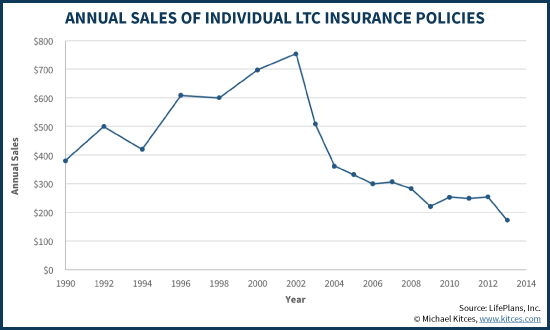

Despite being around for nearly 40 years, and enjoying preferential tax treatment for nearly half that time period, long-term care insurance has struggled to gain momentum in the marketplace. In fact, low interest rates, coupled with low lapse rates, and rising longevity, have come together to drive up long-term care insurance premiums significantly, leading LTC insurance purchases to decline nearly 70% from their peak in 2002.

However, a new approach to long-term care insurance pricing – the Performance LTC policy from John Hancock – is aiming to bring LTCI premiums down. Ironically, the new policies have eliminated any kind of pricing “guarantee” to prevent premiums from rising, but combined that change with an opportunity for policyowners to benefit if investment and claims results are favorable in the future, by accumulating “Flex Credits” that, like dividends from a participating life insurance policy, can be used to reduce future premiums and even allow LTC premiums to vanish, altogether.

The good news of this structure is that it is uniquely suited to benefit if interest rates rise in the future (unlike hybrid life/LTC or annuity/LTC policyowners who may suffer in a higher rate environment). The bad news, however, is that because Hancock is not actually a mutual insurance company, it will still face a fundamental conflict of interest in deciding how much to pay as a Flex Credit to policyowners, versus a dividend to shareholders. Nonetheless, though, the reality is that by allowing LTC insurance premiums more flexibility, Performance LTC may still potentially be less expensive LTCI coverage in the long run!

The Challenge Of Pricing Long-Term Care Insurance Premiums

Long-term care insurance originated primarily as nursing home insurance in the late 1970s, but it didn’t really garner much interest until the 1990s, as the earliest baby boomers began to reach their 50s (and their parents hit their 70s and 80s). Adoption accelerated further after the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in 1996 gave long-term care insurance the tax-qualified treatment it (still) enjoys today.

However, even as long-term care insurance received its favorable tax treatment, in the 20 years since the volume of long-term care insurance being purchased has fallen, and huge swaths of insurers (including even some mega-insurers like MetLife) have left the business altogether. The problem is that when trying to effectively price long-term care insurance – as insurance with a relatively high probability of claims in the first place – relatively “small” mistakes in the underlying actuarial assumptions have a dramatic impact.

For instance, it’s estimated that as little as a 1% change in interest rates correlates to a 15% required change in premiums to keep an LTC insurance policy actuarially sound. Having a 1% lapse rate instead of a 5% lapse rate can increase future claims for an insurer by as much as 50%. And of course, that’s before considering the potential impact of medical advances that prolong life expectancy in the face of serious illnesses (which may be good news for the individual, but can greatly amplify claims against an LTC insurance policy, too)!

In fact, given the difficulty in estimating these key inputs correctly, leading LTC providers like Genworth are struggling to be profitable in issuing long-term care insurance. The combination of falling interest rates and “surprisingly” low lapse rates in the past decade has revealed that pricing was so far off, companies could not honor their original prices, and instead had to request State Insurance Departments to permit premium increases as large as 85% on huge swaths of existing policies (and forcing consumers to decide how to deal with the new higher rates). Yet even with the rate increases, LTC insurers haven’t been able to raise the premiums fast enough to keep up with their earlier underpricing challenges, leading many to just leave the business altogether.

In turn, this dynamic has put significant pressure on long-term care insurance providers to get the pricing “right” up front – which basically means setting the premiums on new policies even higher, to be even more conservative (as if the company has to request a rate increase in the future, it has probably already lost any chance to be profitable on that policy!). As a result, the cost of new LTC insurance policies has exploded even more than the premium rate increases on old ones. Data from LifePlans finds that the cost of a new LTC insurance policy for a 60-year-old increased by 145% from 1995 to 2010.

The end result is that LTC insurance providers find themselves between a rock and a hard place. If the long-term care insurance policy is not priced high enough to protect against these uncertainties in the first place, then the insurer may be unable to regain profitability with rate increases later. Yet raising rates on new policies so much has taken its toll as well, as the number of long-term care insurance policies purchased by consumers fell by a whopping 65% from 2002 to 2012!

The ultimate irony of this situation is now that we “know” lapse rates for long-term care insurance may be no more than 1%, and now that we “know” interest rates can go so low, the risk of needing to raise long-term care insurance premiums in the future has never been lower than it is today. In fact, if interest rates increase, LTC insurance providers may discover that they actually could have priced policies lower than they did. But without knowing when an interest rate increase will occur, LTC insurance providers have no way to know how much premium relief to provide in advance… since there’s been no effective means to make adjustments along the way. Until now.

John Hancock Performance LTC (PLTC) And The Flex Credit Account

To resolve the challenge of wanting to make long-term care insurance premiums more flexible, but having great difficulty being able to adjust the premium itself after the fact, last year John Hancock innovated a new approach to long-term care insurance, which they dubbed their Performance LTC (PLTC) policy.

The key new concept with John Hancock’s Performance LTC is the creation of the “Flex Credit” – a payment that the insurance company makes back to the policyowner every year, in recognition of both favorable investment experience of John Hancock’s General Account (where policy reserves are invested) and the claims experience of the entire block of its Performance LTC policies.

The annual Flex Credit is deposited into a Flex Account, and the balance of the Flex Account can then be used to reduce (i.e., pay for some or all of) the premium of the policy. Which means if interest rates rise (and/or claims turn out to be more favorable than expected), Flex Credits make it possible for the Performance LTC insurance premiums to decline in the future. (Notably, Flex Credits deposited in the Flex Account can also be used to pay for long-term care needs in the future, such as during the policy’s elimination period, instead of just using them to reduce LTC premiums.)

In other words, the Flex Credit of the Performance LTC policy operates similar to a dividend from a participating whole life insurance policy. To the extent that future claims (or the insurance company’s investment returns) turn out to be better than the original (conservative) projections, the ‘excess’ results will be returned to the policyowner in the form of either an "Insurance Credit" or an "Interest Credit", to help reduce future premiums. Given the potential (but still looming uncertainty) for interest rates to rise in the future, this provides the buyer of Hancock’s Performance LTC policy a way to participate in the upside of interest rate increases, even better than Hancock’s prior Benefit Builder Custom Care III policy (and unlike with a hybrid life/LTC or annuity/LTC policy, where the policyowner is far more likely to be adversely impacted by rising rates!).

The added benefit of the Flex Credit structure is that even if John Hancock prices its long-term care insurance “conservatively” – i.e., sets premiums higher than may be necessary for projected claims, just in case the underlying LTC assumptions shift unexpected in the future (as they did in the past!) – if the future turns out to be more favorable, or merely just “normal” as expected, the Flex Credits will just be paid out even faster, reigning in those higher premiums in the future.

Rising LTC Premiums And Flex Credit Offsets

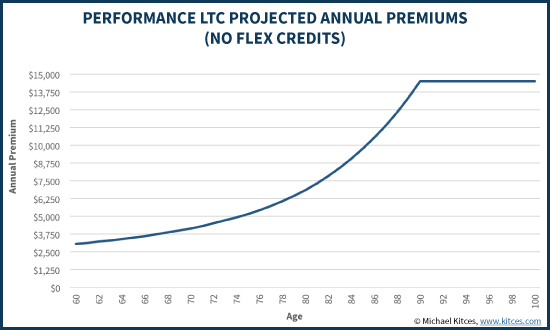

Given this new dynamic, though, Hancock’s Performance LTC policy deliberately prices itself very “conservatively”. In fact, its standard version, with a 3% inflation rider, is assumed to have premiums that will rise every year... potentially quite significantly, if there were no Flex Credits available to offset them. For instance, the chart below shows the expected premiums for a 60-year-old male purchasing a Performance LTC policy with a $200/day benefit, a 5-year benefit period, and the aforementioned 3% compound inflation rider.

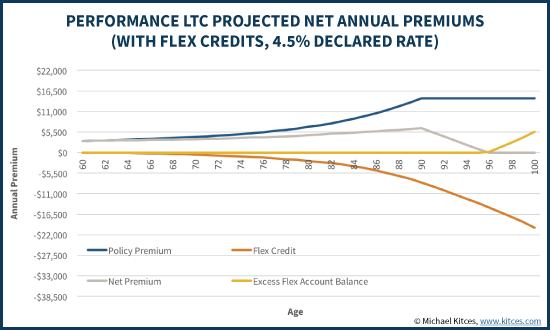

Of course, the caveat is that these premiums would not actually be due unless the policy paid no Flex Credits, ever. Which would require that John Hancock’s General Account never earn a return above the 2.5% “Threshold Rate” required to generate the investment portion of Flex Credits, and furthermore that claims were far higher than expected (e.g., 65% higher due to significant medical advances extending claims periods). Which means even if the investment and claims results are “merely” adverse – for instance, if John Hancock’s General Account only has a Declared Rate of 4.5%, and claims are 35% higher than current expectations – some Flex Credits will still be earned, and the net premiums will be significantly lower than originally projected (albeit still rising for much of the time period).

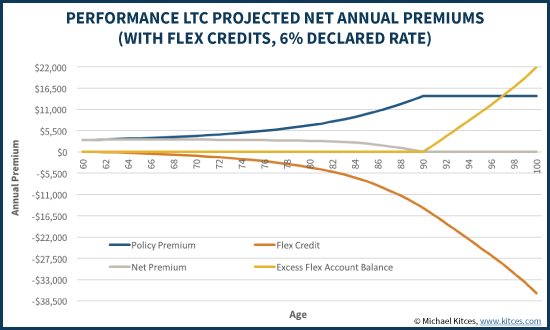

On the other hand, if the claims experience is even more favorable, and interest rates do rise (such that the Declared Rate goes to its available maximum of 6%), the net premium result with accumulating Flex Credits in the Flex Account just looks even better. The version below shows the net premium for the Performance LTC policy at a 6% Declared Rate, and claims that are (still) 10% higher than Hancock’s current expectations.

Notably, in this scenario the results are so strong, the Performance LTC premiums only ever rise cumulatively by about 5% in the first few years (before any material Flex Credits are being paid), and then begin to fall in the years thereafter… such that if the insured is actually still alive in his/her late 80s, the premiums decline significantly, and vanish altogether once the policyowner reaches his/her 90s! In fact, the Flex Credits – which by then are more than enough to offset the entire policy premium, even with all the increases – are so large that the excess balance just accumulates in the Flex Account, forming an additional pool of money that can be used for (non-covered) claims, and/or is simply paid out at the death of the policyowner.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that this more favorable outcome will occur. The actual investment and claims experience for John Hancock’s General Account and its Performance LTC policies may not be this good. But if the results are favorable, the policyowner benefits in the form of the Flex Credit. And alternatively, if the results end out being even better – for instance, if it turns out that Hancock’s claims assumptions are now so conservative, that future claims come in lower than expected – the accumulation of Flex Credits just improves even further.

How Does Performance LTC Pricing Compare To Genworth And Other LTC Providers?

For many prospective LTC insurance buyers, the fact that John Hancock’s Performance LTC premiums are projected to rise – even by a little bit in the relative “good” scenario of moderate claims and higher interest rates – may be concerning. But it’s crucial to recognize that the flexibility of the policy’s pricing has a significant impact on the base premium of Performance LTC in the first place. Because while every other long-term care insurer must price conservatively, once, up front, John Hancock doesn’t need to be as conservative at the beginning, because it knows that premiums will rise to cover future contingencies. On the other hand, if the conservative pricing turns out not to be necessary, the policyowner still benefits.

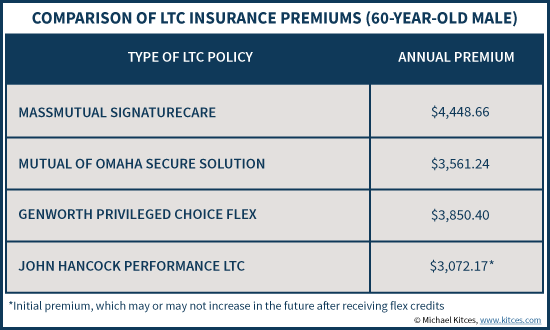

Thus for instance, the chart below compares similar LTC insurance policies from other popular carriers, including the MassMutual SignatureCare policy, the Mutual of Omaha Secure Solution, and Genworth's Privileged Choice Flex 3. All policies are for a 60-year-old male, with a $200/day benefit, 5-year benefit period, and 3% compound inflation rider.

As the quotes reveal, John Hancock’s Performance LTC is far less expensive from the start. As a result, in the scenario where interest rates and claims are favorable but premiums “still” rise by about 5%, the reality is that the Hancock policy will still be far less expensive than the others. In fact, even in the “adverse” scenario with a 4.5% Declared Rate and claims that were 35% above projected, it still takes 10-20 years for the Hancock Performance LTC policy to have higher premiums than the others. And it takes almost 30 years for the cumulative premiums to be higher (since the Performance LTC buyer would have had years of much-lower premiums before they eventually caught up).

In other words, while the premiums of John Hancock’s Performance LTC policy are much more likely to experience at least small changes (given the expected rising premiums and the non-guaranteed nature of the Flex Credits), the policy’s flexibility still allows it to be cheaper than the rest by a significant margin. Or viewed another way, policyowners are actually paying a significant “excess” premium in today’s marketplace to other LTC insurance carriers to obtain that premium “guarantee” (notwithstanding the fact that it’s still not unequivocally guaranteed, because the carriers may still raise rates for an entire class of policyowners in a particular state, as has occurred with some frequency for many of these carriers in the past!).

Caveats And Concerns Of The Performance LTC Insurance From John Hancock

Notwithstanding what appears to be rather appealing pricing for the Performance LTC policy – at least compared to the available alternatives – there are several notable caveats and concerns to consider, both in terms of this new approach to LTCI pricing, and also details of the Performance LTC policy itself.

How Flex Credits Are Calculated

First and foremost, there’s the operation of the Flex Credits themselves. While arguably it takes some highly adverse interest rate and investment results, on top of especially horrific claims experiences, there is still a danger that Flex Credits won’t be paid at all (or at least, at a rate far less than illustrated earlier). The longer it takes interest rates to rise, the less that will be paid in Flex Credits over time. And there are virtually no Flex Credits at all for the first several years (as the insurance company is still recovering its commission and other distribution costs, so the premiums technically aren’t yet being allocated to the insurance company’s reserves to earn a Flex Credit return yet).

In addition, the reality is that the accumulation of Flex Credits will differ depending on the insured…

It’s also important to recognize that if policy results are especially unfavorable for a period of time, where investment results of the General Account are below the Threshold Rate, and/or claims are especially bad, the allocation of Flex Credits can be negative for that year. Notably, negative Flex Credits do not cause the loss of any dollars already paid into the Flex Account, but may mean that year’s premium rises (because there were Flex Credits to offset premiums in the prior year but less or none in the current year). Furthermore, if Flex Credits are negative, the “loss” is carried forward, and there are no future positive Flex Credits until all the prior negative ones are offset. Which means bad results, early on or at any point along the way, could trigger an indirect increase in LTC premiums (either by not getting Flex Credits that were being received in the past, or simply because Performance LTC premiums will rise in every year that [rising] Flex Credits aren’t available to offset them).

No Waiver Of Premium And Other Performance LTC Features

Beyond the structure of the Flex Credits itself, there are some other notable issues to consider with Performance LTC as well.

Most significantly, one key difference of Hancock’s Performance LTC is that the policy does not have a Waiver Of Premium feature – common in virtually all other LTC insurance policies – which eliminates LTC premiums once the insured goes on claim. Instead, the policyowner is actually still required to pay premiums, even while on claim. Furthermore, it’s notable that because claims can actually impact the calculation of Flex Credits, a policy that is paying claims may actually experience an indirect net premium increase at the same time, as the Flex Credits may level off or decrease (even as the underlying base premium continues to rise!).

For those who find the 3% compound inflation rider to be insufficient – given the potential that future long-term care inflation may be higher than this – Performance LTC does offer a 5% compound inflation rider as well. In addition, the 5% inflation rider does not use the annually-rising-premium-offset-by-Flex-Credits structure. Instead, the 5% compounding version has a level premium (before being reduced by Flex Credits). As a result, though, the 5% compound inflation rider is dramatically more expensive than 3% inflation; thus, while the 3% compound inflation rider quoted above has a base premium of $3,072/year (before subsequent premium increases and subsequent Flex Credit offsets), the 5% compound inflation version of the policy is a whopping $9,629/year (such that those who prefer a larger inflation rider will likely choose other LTC insurance carriers, even with the potential for Flex Credits).

On the other hand, the good news is that the Performance LTC policy does still offer a Shared version of the policy for married couples (any accumulated and unused Flex Credits in the Flex Account simply flow to the survivor’s Flex Account balance).

Can You Really Buy Participating LTC From A Non-Mutual LTC Insurance Company?

The idea of having an insurance policy that is “conservatively” priced, with any future improvement in actual claims resulting in a refund to policyowners, is not new. It is the basis for “participating” whole life (and other participating insurance) from mutual insurance companies, which similarly pay a dividend (literally treated as a return of premiums) if future policy results (claims and investment results) are better than originally projected.

However, a key distinction is that when it comes to participating life insurance from a mutual insurance company, the structure “works” because a mutual insurance company is literally owned by its policyowners. So if the policy is priced conservatively and then turns out to perform better than expected, the insurance company “profits” by doing so, but those profits go back to the very policyowners who bought the insurance in the first place. This closed loop system reduces most incentives for the insurance company to try to “game” the payment of dividends – because if the insurance company underpays the dividend and generates a larger profit… it goes back to the policyowners as a dividend anyway.

In the case of John Hancock and its Performance LTC policy, though, the situation is somewhat different. John Hancock is owned by Manulife, and Manulife Financial (ticker symbol: MFC) is a publicly traded shareholder-owned (Canadian) corporation. Which means if Performance LTC policies are “more profitable” than expected, such that the company pays Flex Credits back to the policyowners, those Flex Credits will detract directly from the Manulife profits and the availability of dividends to pay to actual shareholders.

In other words, the fundamental different between Performance LTC’s Flex Credits and the dividends of participating life insurance is that the latter is from a company actually owned by its policyowners and paid to its policyowners, while the former is from a company owned by third-party shareholders but making payments to policyowners. Which means Hancock’s decision about how much to allocate in Flex Credits each year faces a fundamental conflict of interest between serving its policyowners and serving its shareholders.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that anything nefarious is afoot, but it does raise serious questions about the incentives that John Hancock will have to not necessarily pay “the maximum it could pay” in Flex Credits, given that paying less in Flex Credits improves the profitability of the company for its shareholders (who are not the Performance LTC policyowners). In other words, John Hancock may face some perverse incentives to not necessarily maximize the Declared Rate on its General Account, and to be ‘conservative’ in releasing any excess reserves if policy claims really do turn out to be more favorable than expected. Which is concerning, as those are exactly what Performance LTC policyowners are counting on to get the Flex Credits they “need” to keep their premiums from rising precipitously over time!

LTCI Premium Stability And Vanishing Premium LTC Insurance

Notwithstanding the concerns of whether John Hancock has the “right” incentives to maximize Flex Credits for Performance LTC policyowners, arguably this new LTC insurance approach may still be superior to the “traditional” way that long-term care insurance is priced.

The reason, as noted earlier, is that in practice the efforts of insurance companies to “guarantee” long-term care insurance premiums – given the significant uncertainty that is actually involved in doing so – is driving up LTC insurance premiums, to the point that fewer and fewer can afford the coverage at all. In other words, trying to price LTC insurance once, up front, is forcing insurance companies to make the premiums so high – to be conservative, given the challenges of getting subsequent rate increases approved by State Insurance Departments – that it’s causing the premiums to be unaffordable altogether.

By contrast, eliminating the implied rate guarantee for LTC insurance coverage – as John Hancock has done – introduces the possibility, and even the likelihood, that LTC insurance premiums may rise slightly over time (or more rapidly, if Flex Credits ultimately underperform). Nonetheless, it also means those premium increases are likely to be small and gradual over time, and that John Hancock should have very little risk of ever needing to put through some massive 50% - 85%+ premium increase all at once. In part this is because it would simply have raised premiums more evenly over multiple years. But it is also because the ability of premiums to rise slightly over time (paired with not paying out a Flex Credit) also avoids a situation where the insurance company has to wait for state approval to raise premiums, which some suggest has only exacerbated the magnitude of recent rate increases.

Which means ironically, the Performance LTC structure may actually lead to better LTC premium ”stability” – not by necessarily guaranteeing premiums will remain level, but by allowing enough flexibility to reduce the risk they ever need to rise precipitously all at once. Which in turn allows consumers more time to adjust to the higher premiums, conform higher premiums in later years to the declines in other spending that typically come for older retirees, and avoids putting policyowners in the position of deciding what to do about a mega premium increase that hits all at once.

On the other hand, the great challenge of the new Performance LTC approach is that it’s very difficult to assess the likelihood that the current sales illustrations will in any way match what actually occurs in the future. Not merely because the future itself is uncertain, but because a prospective policyowner is very limited in the information that be assessed about the underlying policy assumptions in the first place. In other words, there’s a risk that current sales illustrations are still being overly optimistic in projecting future Flex Credits – such that LTC premiums seem to disappear altogether as the policyowner approaches age 90. And unfortunately, we’ve been here before – participating life insurance policies in the late 1970s and early 1980s were also commonly sold on the assumption that future dividends would cause premiums to vanish within 20 years, and instead the policies so underperformed those projections (as interest rates declined in the 1980s) that it eventually led to a wave of “vanishing premium” class action lawsuits! Will Performance LTC someday face its own questions as future in-force illustrations in 5-10 years fail to align to the original sales illustrations?

Nonetheless, the fact remains that the ‘traditional’ approach to LTC insurance has not fared well for the industry, and arguably the nature of trying to “guarantee” LTC insurance premiums has only exacerbated the situation. Which means eliminating the guarantee and creating a structure where LTC premiums can ‘float’ (based on rising premiums and not-guaranteed-to-offset Flex Credits to reduce them) may bring down the cost of LTC insurance on that basis alone. And the fact that we may see rising interest rates in the coming years – which should only further improve the payout of Flex Credits – means Performance LTC is uniquely positioned as the type of LTC insurance most likely to benefit from rising rates (unlike hybrid LTC insurance policyowners, who may suffer from the failure to participate in higher interest rates).

Still, at a minimum, those who consider buying the new Performance LTC policies from John Hancock will need to be cognizant of the fact that while premium increases may be more gradual, it remains to be seen whether Hancock will really be able to pay out Flex Credits as projected, even with rising interest rates, especially when doing so conflicts with company’s desire to maximize profitability for its shareholders!

Thanks to Jerry Skapyak and Mark Maurer of Low Load Insurance Services for their assistance in providing some of the LTC insurance quotes and supporting information used in this article.

So what do you think? Is "participating LTC insurance" a good strategy to manage the challenges of LTCI pricing? Do you "trust" that John Hancock will pay the Flex Credits as expected? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!