Executive Summary

While affording both college and retirement is difficult for many families, some retirees find themselves in the fortunate position of having enough to cover their retirement years and still have something left over to help other family members pay for college.

Yet the challenge is that if not done carefully, using a grandparent-owned 529 plan or gifting assets from a grandparent to grandchild for college can adversely impact the grandchild’s own ability to qualify for financial aid, implicitly diminishing the value of the gift.

For instance, a grandparent-owned 529 plan is not treated as an asset of the grandchild for financial aid purposes, but distributions from a grandparent-owned 529 plan may show up on the grandchild’s FAFSA financial aid form (even if it’s a qualified tax-free distribution!). Similarly, gifts of appreciated assets from a grandparent to a grandchild may be eligible for 0% capital gains tax rates, if able to avoid the kiddie tax, but may still adversely impact the student’s income on the FAFSA. And for grandparents trying to diminish their own estates, often the best tactic is simply to make tuition payments directly to the college institution, which can be done above and beyond the annual gift tax exclusion limits.

Ultimately, the reality is that grandparents actually have numerous opportunities for preferential income and/or estate tax treatment by helping fund college for grandchildren (or other family members). But the financial aid rules – especially when considering the new “prior-prior year” (PPY) rules for which year’s income is reported on the FAFSA – means that coordinating the timing of the various strategies is crucial to avoid adverse financial aid outcomes!

Grandparent Funding Of 529 Plans For College Savings

Contributions of up to $14,000/year (the annual gift exclusion in 2016, indexed annually for inflation) can be made to a 529 college savings plan without triggering any gift taxes. In addition, contributors are eligible to make larger-than-$14,000 gifts and average them out over 5 years under IRC Section 529(c)(2)(B), allowing as much as a $70,000 contribution to a particular 529 plan beneficiary in a single year (albeit with no subsequent gifts in the next 5 years as the lump sum contribution is averaged out).

Financial Aid For Child-Owned vs Grandparent-Owned 529 College Savings Plans

However, the question that often arises in the case of grandparents funding a 529 plan is in whose name the 529 plan should be. Is it better to create the 529 plan with the grandparents as the owner/participant of the 529 plan (with the grandchild as the education beneficiary), or to put the 529 plan in the grandchild’s name outright? Or should the grandparents contribute to a(n existing or new) 529 plan in the name of the grandchild’s parents instead?

While the income tax treatment of the 529 distributions for the grandchild’s education will be the same in all three circumstances, the key distinction is the treatment for financial aid purposes.

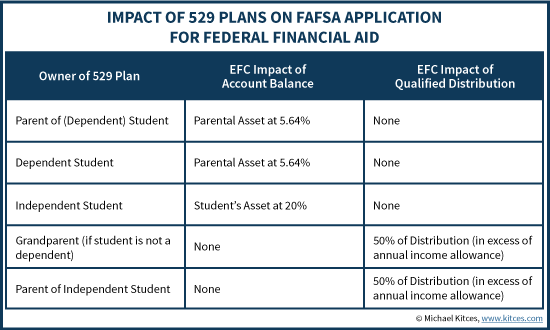

When a 529 plan is owned by the parents of the student, it is treated as a parental asset for financial aid purposes, which means 5.64% of the value of the 529 plan is counted towards the Expected Family Contribution (EFC). As the FAFSA is filed annually, this amount is recalculated annually on the typically-declining 529 plan account balance as it is spent down. On the other hand, to the extent that the distributions are tax-free qualified distributions from the 529 plan, they are not counted as “income” for FAFSA purposes.

When a 529 plan is owned by the student themselves (where the student is both the account owner and beneficiary), the asset is still treated as a “parental” asset for the purposes of financial aid if the student is a dependent. This was a change under the College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007 that went effective on July 1, 2009; previously, student-owned 529 plans were treated as an asset of the student. However, if the student is not a dependent of the parents for tax purposes (i.e., is financially “independent”), the student-owned 529 plan is treated as an asset of the student, which causes 20% of the account balance to count towards the student’s EFC calculation on the FAFSA. Either way, qualified distributions from the 529 plan for education purposes are not counted as income for financial aid determination.

With a grandparent-owned 529 plan, though, the treatment is different. When a 529 plan is owned by someone besides the custodial parent/guardian of a dependent student (and besides the student themselves), it is not counted as an asset for financial aid purposes (neither at the parents’ EFC rate nor the student’s). However, when distributions are made from a grandparent-owned 529 plan, it is treated as income of the student (even though the income is “tax-free” for income tax purposes), which can be highly adverse for financial aid purposes (assessed at a rate of 50% of the student’s income above a $6,260 income allowance)! (Notably, these rules apply only if the grandparent is not the legal guardian of the student; if the grandparent is the guardian and the student is a dependent, the “parental” rules apply instead.)

Notably, while these rules apply for the FAFSA application for Federal financial aid, some colleges use the CSS/Financial Aid PROFILE from the College Board instead. With a CSS application, all 529 plans for the benefit of the student are reported and treated similarly as available assets, regardless of whether they are student-, parent-, or grandparent-owned.

Gifting Appreciated Investments For Late Stage College Funding

Funding 529 college savings plans can be an appealing option for grandparents that are getting involved early, where there is time for the investments in the 529 plan to actually grow and compound tax-free. However, if the student is already about to go to college, or is it college, contributing to a 529 plan isn’t very helpful, and instead other late stage college funding tactics are necessary.

One appealing option is to gift appreciated assets that are held in the name of the grandparents to the student, in order to sell them in the student’s name, and use the proceeds to fund college tuition or other student expenses. While the $14,000 annual gift tax exclusion limits must still be navigated, the virtue of gifting the appreciated assets – as opposed to the grandparents simply selling the investments and transferring the proceeds to the student/grandchild – is that gifting investments in-kind allows for the cost basis to carry over to the recipient. Which means the subsequent sale shifts the capital gains to the grandchild, and may benefit from the student’s lower tax brackets (including, possibly, the 0% long-term capital gains rate).

The caveat to this strategy is the so-called “kiddie tax”, which still applies to full-time college students under age 24, unless they have earned income in excess of one-half of their support needs (or if the child is already married and filing his/her tax return jointly with a spouse). As a result, gifting appreciated investments will be most appealing for students who can somehow avoid the kiddie tax, either by being married, by not being a full-time student, by being age 24 or older (e.g., going to graduate school), or who are going to school while also working and generate enough earned income to cover at least ½ of their own support.

It’s also important to note that while gifting appreciated securities to the child and selling them in his/her name may be an effective tactic to avoid long-term capital gains taxes at the grandparents’ tax rates, the investment is still an asset in the name of the student, and the gains from the sale are still income in the name of the student (even if subject to a 0% tax rate, the gains are still income). Either of these could impact subsequent years of financial aid eligibility. In particular, even if the asset is received as a gift and then liquidated and spent in the same year, so it never shows up as an asset on the FAFSA, the gains from the sale will still show up as income).

Similarly, even if the grandparents simply gift securities to the parents of the student – which may still generate some capital gains tax savings if the parents have a lower tax bracket than the grandparents – if the investments are held they will be reported as an asset of the parents, and even if liquidated and spent in the same year as received, the sale of investments in the name of the parents will also still show up as “income” on the FAFSA and may adversely impact subsequent financial aid eligibility.

Which Income Years Count For Financial Aid Under Prior-Prior Year (PPY) Rules

While both contributions to and distributions from 529 plans can potentially show up as an asset or income on the FAFSA for financial aid purposes, along similarly a gift of appreciated securities to the student may end out being reported as an asset or income, it’s crucial to recognize which years will be impacted by this determination.

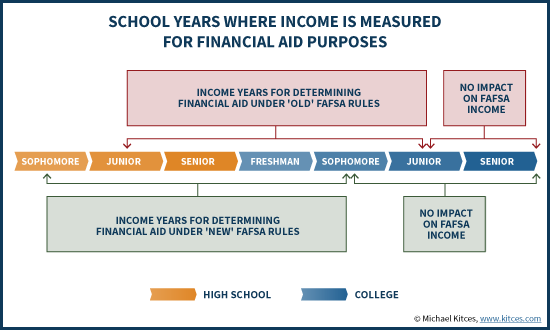

In the past, income in a current year would count towards financial aid determination in the subsequent year. Thus, for instance, the receipt of an asset or the sale/liquidation of an investment in 2016 would count on the FAFSA in 2017 (for the school year that began in the fall of 2017). Given this dynamic, any asset or income events as late as the first half of junior year could still show up on the FAFSA application for the senior year, and consequently experts often advised to wait until the student’s senior year to engage in such tactics like liquidating grandparent-owned 529 plans.

However, in the fall of 2015, President Obama signed an executive order that adopted new “prior-prior year” (PPY) rules for financial aid. Under the new rules, which will go into effect for the 2017-2018 school, the FAFSA financial aid application will use income from the prior prior year. Thus for instance, a student matriculating in 2017 will use income not from the prior 2016 tax year, but from the prior-prior 2015 tax year. In turn, this means that the current 2016 tax year will be used for financial aid not in the upcoming 2017 school year, but for the school year that begins in 2018 instead.

The significance of these new PPY rules is that it shifts which tax years are relevant when looking at college funding strategies that impact income. In the past, the relevant time window extended from the middle of junior year in high school, until the middle of the junior year of college, and students weren’t “in the clear” until their FAFSA for their senior year had been filed (generally sometime around the end of their junior year). Under the new rules, however, tax events as late as the second half of sophomore year in high school become relevant (because it will fall in the prior-prior year to when the student matriculates to college); on the other hand, once the student is more than half way through sophomore year of college, any subsequent income tax events in the junior or senior years will be in the clear, because even the senior year’s FAFSA will be wrapped up based on the prior-prior year tax return that spans the end-of-freshman-and-beginning-of-sophomore-years in college (at least for students who finish in 4 years!).

Grandparents Paying Tuition Gift-Tax-Free Directly To A College Institution

Notably, in addition to the “usual” rules for the $14,000 annual gift tax exclusion – which applies whether gifts are made in-kind or in cash, to a 529 plan or outright to the child – under IRC Section 2503(e), a payment of either college tuition (but not other educational expenses) or for medical expenses, directly to the associated educational institutional or medical facility, does not count towards the annual gift exclusion.

In other words, a grandparent could write a check on behalf of a grandchild student for $15,000, $30,000, or even $50,000/year for the most expensive tuition in the country, and the payment is entirely free of gift taxes. No use of the annual gift tax exclusion, nor of the lifetime gift exemption. The amount is just outright gift tax free.

However, the direct payment of tuition on behalf of a student may potentially be treated as either a direct financial resource of the student (which can reduced needs-based aid on a dollar-for-dollar basis), or as a form of untaxed income of the child (which can reduce aid by 50% of the amount paid); since both of these would be reflected in the subsequent financial aid determination, grandparents paying for tuition directly should wait until the later years of college, past the window for the last FAFSA filing, if qualifying for financial aid is a concern.

Coordinating The Timing of Grandparent College Funding

Given these dynamics of outright gift-tax-free payments of tuition directly to a college, the ability to fund a 529 plan (either in the name of the grandparent or the child), or gifting appreciated assets to the grandchild student, which is the best course of action, and how should families coordinate between them?

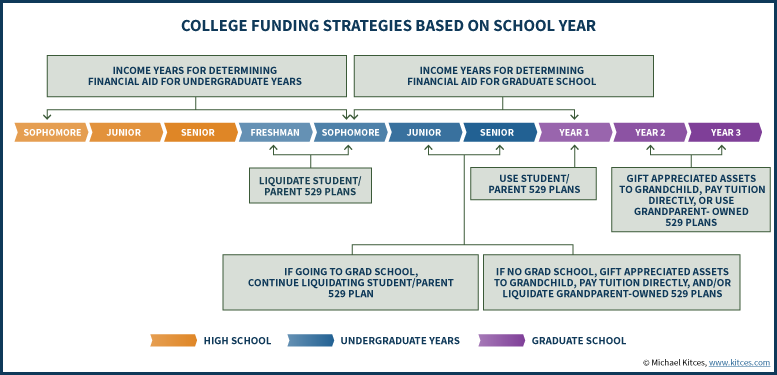

The first key is simply to recognize the age of the student and when he/she is expected to go to college. For those looking to make gifts to support children now, who are still many years away from college, funding a grandparent-owned 529 plan will likely be the most appealing, as it allows for tax-free compounding growth for the child. For grandparents who have an outright estate tax problem themselves, it also begins to shift assets out of their estate, and it may be especially appealing to use the 5-year-averaging provision.

In situations where grandparent-owned 529 plans are involved, though, it’s important to recognize that those plans should only be liquidated during the student’s last two years in college (ostensibly, junior and senior years for those on the 4-year plan!), to ensure that the grandparent-owned 529 plan distributions don’t foul up the student’s EFC calculations when filing the FAFSA. In the early years of college, the grandchild should use their own assets or parental assets. Notably, if the grandchild plans to go to graduate school, it may be appealing to further delay the use of grandparent-owned 529 plans so the distributions during the undergraduate years don’t impact financial aid for graduate school.

Gifting strategies, where appreciated investments are transferred directly to the student, will be most appealing for those who are able to avoid the kiddie tax. This might be because the student is working at least part-time and is able to provide for one-half of their own support, or because they are not a full-time student. In addition, because the kiddie tax rules only apply to full-time students under the age of 24, gifting appreciated securities may be especially appealing as a tactic to fund graduate school, where the student grandchild will be over the age threshold for the kiddie tax, but may still have income low enough to pay little-or-no capital gains taxes, because the 0% long-term capital gains tax rate, and the potential offset of any eligible Lifetime Learning Credit.

Given these coordination tactics, using the student’s own 529 plans – either in the student’s name or the parent’s name – will be most appealing to fund the early years of college. Both because most of the other tactics are especially inhospitable to funding college in the early years – due to their impact on subsequent financial aid – and also because spending down assets that are counted for financial aid are especially appealing to spend down in the early years, as that may improve eligibility for college aid later. For instance, if the student spends down all 529 plan assets in the first two years, eligibility for financial aid may be improved, which diminishes the amount that grandparents need to supplement with their own direct-payment gifts or grandparent-owned-529-plan distributions (after the student is past the FAFSA PPY window).

The bottom line is that ultimately, grandparents who want to help fund college for a grandchild do have the opportunity to do so in a manner that helps the family, without impairing the student’s ability to qualify for financial aid, at least for some years. However, it’s crucial to consider the timing of the payments, whether as gifts to the grandchild, payments directly to the educational institution, or distributions from a 529 plan, to minimize any impact to financial aid along the way!

So what do you think? Do you help grandparents coordinate assistance in funding college expenses for grandchildren? Are there other tactics that you recommend?