Executive Summary

The requirement that a financial advisor must “Know Your Client”, including his/her tolerance for taking risks, is a universal requirement amongst investment regulators around the world.

Yet a recent survey of the global landscape for best practices in risk profiling by Canadian financial planning software provider PlanPlus reveals a disturbing lack of quality risk tolerance questionnaires (RTQ) and support tools for financial advisors. In part, this appears to be driven by the fact that regulators articulate the principle of “know your client’s risk tolerance” but provide little guidance on how it should be done to ensure that it’s right. And to a large extent, the problem stems from the reality that neither regulators, academics, nor advisors themselves, even have agreement on exactly what key factors of a client’s “risk profile” should be evaluated in the first place.

Nonetheless, a growing base of academic research is beginning to articulate a clear risk profiling framework, from recognizing the separation of risk tolerance from risk capacity, the role of risk perception (and misperceptions) on client behavior, and how “risk composure” (the stability of a client’s perceptions of risk) itself can vary from one cline to the next. Of course, just because these factors can be identified doesn’t make them easy to measure with a questionnaire, especially when it comes to “subjective” abstract traits like risk tolerance. On the other hand, the research suggests that financial advisors just trying to interview clients about risk may not be doing a better job, either.

In the end, the optimal approach may eventually be a combination of both, where psychometrically designed risk tolerance questionnaires assess a client’s willingness to pursue risky trade-offs, and the financial advisor can then assess the client’s risk capacity, financial goals, and ability to achieve their objectives given the constraint of their tolerance. And ultimately, an effective risk tolerance questionnaire may not only make it easier to properly match investment solutions to a client’s needs, but also make it easier to manage client risk perceptions and investment expectations on an ongoing basis. Or at least identify which clients are most likely to be challenged when the next bear market comes along!

PlanPlus Searches For Global Best Practices In Investment Risk Profiling

Assessing a client’s risk tolerance, as a part of providing investment management advice or investment product recommendations, is universally recognized as essential by regulators around the globe.

Notably, though, there’s a wide range of perspectives amongst regulators about what, exactly, “risk tolerance” actually is, how it should be measured, what factors are and are not relevant, and how those factors should be weighted when evaluating if an investment recommendation was appropriate or not.

To understand the landscape, the Ontario Securities Commission of Canada engaged PlanPlus (a leading financial planning software provider in Canada that has a global footprint, albeit little presence in the US) to assemble a research team that would compare Canadian practices on risk tolerance assessments to the best practices globally.

Unfortunately, though, what the researchers found was that most regulators around the world are “principles-based” in requiring that advisors understand and assess the client’s risk profile – an essential step fulfill any advisor’s “Know Your Client” (KYC) obligations – yet provide little guidance about how, exactly, that should be done.

Of course, if there was a clear and universally accepted academic framework for evaluating risk tolerance, this might not necessarily be an issue. For instance, in the U.S., an investment fiduciary has an obligation to provide the advice that a prudent expert would have given a similar client in similar circumstances. And although this principles-based “prudent expert” standard isn’t explicitly defined, the courts have recognized it to mean that the expert should have followed the principles of the academic Modern Portfolio Theory framework. Yet when it comes to risk tolerance, regulators have provided a principles-based expectation and obligation on advisors to make an assessment, but without any acknowledgement of the missing academic framework that would/should clarify how advisors actually do it.

In fact, the researchers found that there’s a surprising paucity of any academically research to validate most key concepts associated with a client risk profile. The situation is further complicated by the fact that there isn’t even clear agreement about what all the relevant factors are that should be considered, not to mention how they should be incorporated together to make a recommendation. And what little research has been done is difficult to bring together, because there isn’t even a consistent usage of terms regarding risk tolerance and a client’s overall risk profile!

Breaking Apart The Risk Profile – Tolerance, Capacity, and Risk Perception

From the academic perspective, those who study consumer behaviors around risk and how it influences investment decisions are converging on three core constructs.

The first is risk tolerance itself. In the academic context, risk tolerance very narrowly and specifically refers to a client’s willingness to take on risk – i.e., to pursue an uncertain positive outcome, with the potential that a negative outcome could result instead. Those who have greater risk tolerance are more willing to engage in larger “risky trade-off” scenarios, while those with less risk tolerance tend to avoid them. Notably, some research in this regard focuses on risk aversion, or the dislike a client has towards risk or falling below a certain income/wealth threshold. Ultimately, though, risk aversion can be viewed as the opposite side of the same coin (e.g., an unwillingness to take risks – low risk tolerance – is akin to having a high risk aversion).

The second construct is risk capacity, or the client’s financial ability (in dollars and cents terms) to endure a potential financial loss, and still be able to achieve his/her goals. Of course, whether goals can be achieved in the event of a risky/bad outcome depends on what the goal is in the first place. And some goals are so aggressive that they may actually necessitate taking greater risk just to be achievable (which means the goal itself is risky, and has a higher “risk need” associated with it). Notably, though, risk capacity and the associated risk need to achieve a goal exist independently of the client’s risk tolerance. The mere fact that a client can afford to take risk, or needs to take risk, doesn’t mean he/she wants to or is willing to take risk (though of course, a risky goal for a low-risk-tolerance client implies that it might be time to find a new goal!).

The third construct is to recognize that different clients have different risk perceptions – how risky they think markets (or rather, their investments) are in the first place. The key point is that if perceptions are (or become) misaligned with reality, investors may engage in “surprising” behavior that seems inconsistent with their risk tolerance. For instance, an individual who is highly risk tolerant, but has the (mis-)perception that a calamitous economic event will cause the market to crash to zero, might still want to sell everything and go to cash. Even though he/she is tolerant of risk, no one wants to own an investment going to zero! In addition, the research suggests that some people may have better risk composure than others; in other words, some investors can keep their composure and maintain a consistent perception of the potential risks around them, while others have risk perceptions that are more likely to move wildly. And of course, perceptions of risk themselves also vary by the information that the individual has available to them – poor financial literacy and education can increase the likelihood of risk misperception, as can media coverage of scary/risky events (triggering the availability bias).

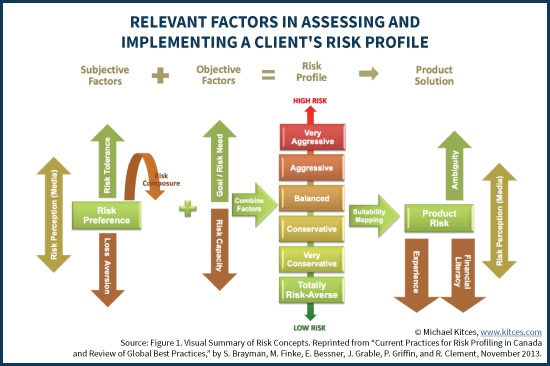

Notably, in this context, risk capacity is an objective measure (the dollars-and-cents mathematical analysis of the consequences of risky events), while risk tolerance (and risk perception) remains more subjective (an assessment of an abstract psychological trait). And it’s the combination of all of those subjection and objective factors that characterize the client’s entire “risk profile”, which in turn will lead to investment recommendations that may vary from very-aggressive to very-conservative.

Of course, even after evaluating the objective and subjective domains of the risk profile, it’s still necessary to actually map the results of the risk assessment to actual investment solutions… which again entails understanding both the objective risk of the investment product, how it fits into the client’s risk capacity and needs and goals, and also the subjective perceived riskiness of the investment (as even an objectively appropriate investment may subjectively seem overly risky if the client misperceives/misjudges the risk of the solution).

The Challenge Of Designing Good Risk Profiling Tools And Assessments

The good news of our increasingly robust understanding of all the different dimensions of a client’s risk profile is that it allows us to better match investment solutions to client goals while also being consistent with their tolerance for risk. The bad news, however, is that when there are so many factors involved – and “sub-factors” that are relevant as well (e.g., tolerance for risk based on upside potential may not be a mirror image of downside risk aversion, as prospect theory has shown) – it’s difficult to figure out how to blend them all together for an appropriate recommended solution.

In addition, the reality is that it’s difficult to measure the subjective aspects of risk tolerance itself, simply because it’s the representation of an abstract psychological trait in the first place. In other words, we can’t just objectively look into someone’s brain and figure out what their risk tolerance is. Instead, we have to ask questions, evaluate the responses, and try to figure out how clients feel about their willingness to take risky trade-offs, and how they perceive the risks around them.

Unfortunately, though, many risk tolerance questionnaires (RTQs) don’t actually do a very good job of helping to predict a client’s actual investment behavior during volatile markets, particularly when they ask about how the investor believes he/she would behave in the event of a significant financial loss. In part, this appears to be due to differences from one investor to the next as to what constitutes a “risky” and undesirable loss in the first place, which can be based on sometimes-arbitrary reference points. An investor whose portfolio recently ran up from $1M to $1.2M may not stress about a subsequent $200,000 loss (because they’ve still got their $1M, and the lost gains were just “house money” to them), while someone who just inherited $2M (and uses the full $2M as a reference point) may be far more stressed about the same dollar amount decline (even though it’s actually a smaller percentage loss). So an RTQ that asks about the consequences of a $200,000 loss would get somewhat counterintuitive responses (where the wealthier client is more averse simply because of a different reference point for “losses”).

The situation is further complicated by the fact that when we take RTQs, we tend to answer the questions calmly and rationally, but when risky events occur, we may respond emotionally (literally using a different part of our brain). Known as the “dual self” or “dual process” theory, this disconnect between how we react to risky events in real time, and our (rational) expectation of how we will react, makes it challenging to simply ask consumers (in the hopes of getting a good answer) about their tolerance for taking future risks.

Fortunately, though, while questions like “how would you react if the markets declined by X%” aren’t very effective at evaluating our likely tolerance for risk in real time, it does appear feasible to get at least some understanding of how a particular investor will likely behave in the face of a risky event. The challenge is greater for younger investors, along with those who have poor financial literacy, because they’re even less capable of making financial self-assessments (due to the lack of experience, knowledge, or both). Nonetheless, one study found that when we’re simply asked whether we’re more concerned about possible losses or potential gains, we can reasonably self-assess our preference (which at least partially reflects risk tolerance). For instance, an investor’s risk tolerance (and their likelihood of going to cash in a financial crisis) can be at least partially predicted by their willingness to engage in risky income trade-offs (e.g., “would you prefer a job with smaller pay increases and more job security, or one with bigger pay increases but less job security?”).

In combination, the research suggests that it really is feasible to get some good perspective on an investor’s risk tolerance, and how it may vary from one person to the next. In fact, there is an entire science of “psychometrics” – the process for making good tools to measure abstract psychological traits – that can be applied to formulate an effective risk tolerance questionnaire.

Finding a balance is still challenging, though, as neither clients nor advisors seem willing to use questionnaires that have “too many” questions (although Guillemette, Finke, and Gilliam found that a small number of high quality subjective risk tolerance questions can still be reliable). Still, though, the impact of a good risk tolerance questionnaire is striking – one study found that advisors trying to assess client risk tolerance with a conversational interview had only a 0.4 correlation to the client’s actual psychometrically-measured risk tolerance. In other words, a well-designed RTQ is actually far more effective than an advisor’s professional (but highly subjective and potentially-business-model-biased) judgment.

The Sorry State Of Current Risk Tolerance Questionnaires (RTQs) And Risk Profiling Tools

When looking across the globe, the PlanPlus research team found that there are still surprisingly few risk tolerance and risk profiling solutions available for advisors, with only about 10 solution providers of any broad reach. And amongst those providers, only 30% were able to document any form of psychometric validity to their risk tolerance questions and process itself, and few were even clear about defining their terminology and focus on what exactly they purported to measure (or not) in the first place (e.g., just tolerance, or also capacity, or also perception, etc.).

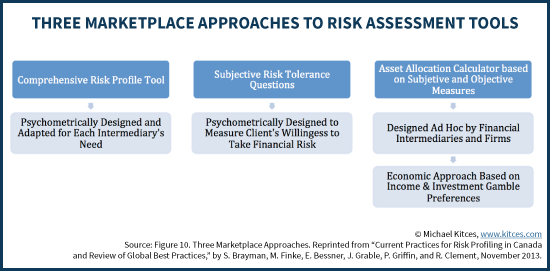

Amongst the available providers, the researchers characterized them into one of three categories: a) Comprehensive Risk Profiling tools, which used psychometrically designed questions that were adapted for (and mapped to) the company’s specific products and services; b) Risk-Tolerance-Only questionnaires, which focused solely on effectively measuring subjective risk tolerance (with the idea that it was the advisor’s job to fit the risk tolerance results into the rest of the picture, including risk capacity and financial goals, to make appropriate recommendations; and c) Asset Allocation Calculators that tended to combine the subjective aspects (risk tolerance) and the objective ones (risk capacity and time horizon) to formulate an asset allocation recommendation.

While arguably any of these can be reasonable approaches, when used appropriately, unfortunately few of the solutions were clear to even distinguish their limitations. All three types held themselves out similarly as “risk tolerance” or “risk profiling” solutions, despite their substantively different approaches, varying degrees of actual psychometric validation of the methodology, and thoroughness of their solution (e.g., “just” for asset allocation, or a more holistic risk tolerance analysis). For instance, here in the U.S., FinaMetrica would fit into the "Subjective Risk Tolerance Questions" category, while Riskalyze better fits as a tool to determine asset allocation based on gamble preferences; yet both frame themselves as "risk tolerance" or "risk profiling" tools without a clear distinction between them.

Furthermore, in Canada (where the analysis was based), only 10% of the risk tolerance solution providers have been validated in any way, and only 16% were even “fit for purpose” (with the rest either using poorly constructed questions, hopelessly conflated different factors, grossly overweighting a particular factor, or simply had no mechanism to actually identify highly risk averse consumers). And it’s not clear that an evaluation of most risk tolerance questionnaires would fare any better here in the U.S., either.

The Future Of (Better) Assessments Of Risk Tolerance

The poor state of affairs in risk tolerance questionnaires – both in Canada, and around the world – suggests that there is ample room for improvement.

However, the PlanPlus researchers suggest that there will be little progress until we first get agreement on a common set of terminology and the associated definitions for key terms pertaining to risk profiling (e.g., for risk tolerance and risk capacity, the difference between those and risk perception, etc.). And realistically, this change may have to be driven by regulators, given that regulators universally seem to require some kind of risk tolerance assessment process as a part of the advisor’s Know Your Client obligations, and if regulators aren’t clear about the terminology when writing the KYC requirements, advisors (and the solutions for them) aren’t likely to fill the void.

And ironically, the challenge of getting clearer about the nuances of risk profiling is that as more factors are introduced, it becomes both more difficult to measure them, and more complex to figure out how to fit them back together in order to craft an appropriate recommendation. Even relatively “simple” conceptual adjustments – like separating risk capacity from risk tolerance – have profound consequences relative to the ‘traditional’ approach in risk profiling. For instance, when analyzed separately, younger clients with long time horizons would not always have aggressive portfolios (because even if they have the risk capacity for it, they may not have the tolerance).

Perhaps the greatest challenge in improving the assessment of risk tolerance, though, is simply figuring out what the role of a questionnaire should or should not be in the first place. Ironically, many of today’s risk tolerance questionnaires are so badly designed, they may actually be worse than using no questionnaire at all, and/or simply allowing financial advisors to make their own professional-albeit-subjective assessment. Yet the potential remains that if advisors begin to actually insist on risk tolerance questionnaires that are actually psychometrically validated as such – and/or regulators require it on their behalf – that there may be a breakthrough in the adoption (and actual usefulness) of risk tolerance questionnaires.

Fortunately, finally getting a “good” risk tolerance questionnaire doesn’t obviate the need for a good financial advisor. The PlanPlus authors suggest that the best balance may be to have RTQs focus on just risk tolerance, and allow the financial advisor as a professional to determine the optimal investment/portfolio solution that incorporates that risk tolerance, along with the client’s risk capacity and financial goals. And because at least some clients may have unusual personal circumstances that don’t fit the “normal” risk tolerance questionnaire, there can always be a role for the professional advisor to identify situations where it’s necessary to ‘override’ the risk tolerance questionnaire based on additional factors or nuances. In fact, regulators around the world – including here in the US – have raised concerns that a purely automated (e.g., “robo”) risk tolerance questionnaire process could miss out on key client information (that the questionnaire didn’t know to ask in advance), and that a financial advisor should be involved at least to affirm the appropriateness of the questionnaire’s results.

In the long run, though, the greatest opportunity of improving risk tolerance questionnaires and overall risk profiling may be the way it helps financial advisors to better manage ongoing client relationships. After all, the clearer we are about a client’s ‘true’ risk tolerance, the easier it is to identify clients who may have risk misperceptions (e.g., the client who really is risk tolerance, but is acting risk averse, and therefore may be over-estimating their actual risk). And the potential to someday determine how to measure risk composure introduces the possibility of actual knowing, in advance, which clients are most likely to panic during turbulent markets, and therefore who might need extra education, guidance, or hand-holding when the next bear market comes.

But at a minimum, the PlanPlus study reveals that while many advisors may be frustrated that traditional risk tolerance questionnaires seem to do a poor job of predicting actual client investor behavior in times of risk, that may not be a failure of the approach of trying to assess risk tolerance, but simply a recognition that there’s still a lot of room for improvement to do it better in the first place.

So what do you think? Do you find risk tolerance questionnaires to be helpful with clients? If so, what tool do you use? If not, do you think it’s because questionnaires “don’t work”, or because you haven’t had access to a properly designed one? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

I’ve seen a lot of “risk profile” forms from insurance companies, B/D’s, fund companies, etc. and few (if any) impressed me. I used to hate making clients complete them so I could check a completed box for compliance purposes, when I gathered little value from them.

Some of the newer models are interesting and I think progress is being made; however, I have yet to see any of them priced for the solo practitioner.

Michael, do you know of any options for us lone rangers?

Elliott Weir

III Financial

I use a three-factor approach to risk (from Larry Swedroe), which assesses the clients willingness, ability, and need to take risk. For willingness, I go through a standard risk tolerance questionnaire *with* the client (I find that I learn a lot about their real risk tolerance by doing it together), and this sets the maximum equity percentage that I would consider. Ability to take risk is a discussion about the impact of a “risk event” on their financial plan and situation. Need to take risk is a discussion about the return the client needs to meet their financial goals. If they can meet their goals at a very low rate of return, then it makes sense to consider a less risky portfolio, even if they have a high risk tolerance.

All three of these feed into the eventual asset allocation recommendation. I’d love feedback on this approach!

The problem is that questionaires really don’t get the job done. Clients themselves often are unsure of their true risk tolerance. Recently I have had clients tell me they are aggressive, but if the market drops 10% they’d want to sell. An agressive investor should say, “when the market drops 10%, I want to buy”. Questionaires also don’t account for the experience the advisor has had with the client. Sometimes I know how my clients will react to events better than they do, but there is no way to quantify that.

Is that a problem with questionnaires? Or a problem with BAD questionnaires?

Have you ever tested this using a psychometrically validated risk tolerance questionnaire?

The fact that the tools advisors are given lack validity doesn’t mean NO assessment tool has validity…

-Michael

Michael,

Have you tried out different psychometrically validated risk tolerance questionnaires? I was wondering if you had found some to be more helpful in using them with clients. I have never used one, but have seen FinaMetrica mentioned and I also read a little about Pocket Risk and Tolerisk. Thanks.

Michael,

I am newly working with a Fintech startup in beta, looking to launch in November. Would you be open to me sending you our brief 1 risk questionnaire? It is a small piece, but an important piece of our platform and I would definitely like your feedback on it. We have taken a slightly of a different approach to what I have seen elsewhere, inspired byDaniel Khaneman’s Prospect Theory.

Regards,

-Mojan

I’ve used Finametrica for a long time and it seems best to use it as only one part of my assessment, much like “Linden” described using 3 factors. For clients with more than enough money to meet their needs, I discuss the dichotomy of their options – they could AFFORD to have a higher risk tolerance and shoot for higher long-term returns OR they could AFFORD to stay safe and sleep better if volatility drives them nuts. I also try to educate clients on impact of being overly conservative for the long-term because they are scared of the unknown.

I have been using FinaMetrica for a couple of years, to measure risk tolerance. A few of the questions don’t make sense to some clients; since we always walk through the results, we clear that up as we go. I like the term “risk perception” and realize that I have recognized the need to go over client’s fears about the impact of economic and geopolitical events; I’ve been using Hidden Levers to walk through those concerns. All my work with clients starts with their financial plan – and modest long term return expectations – which helps with the risk capacity question. From all of this, we are able to converge on a allocation and formulate an investment policy that’s tailored to the client; there’s no way to boil this process down to your “number” and a pre-selected ideal portfolio allocation on the spot. I sometimes need to talk clients “down” from an overly risky stance, or “up” from a degree of risk aversion that would hinder their financial plan outcome over time. So there’s still a lot of “art” involved, although I think the “science” part is getting better.

At least a part of the part of the problem is that there are so many kinds of “risk”. Part of the genius of what Markowitz did was to focus on a limited form of “risk”, namely volatility, but how many clients are really concerned with volatility as they are with “the fear of permanent loss” – yet that, as they say, “is a whole different kettle of fish.”

Of course, in reality, there are no “risk free” investments and the notion that there is some kind of a continuum of risk with a corresponding trade-off of return is not nearly as meaningful as it seems. Yet without a single definition of risk, how meaningful can those pyschometric studies be? On the other hand, if we limit our notion of “risk tolerance” to “likelihood to panic in a major downturn” why not just ask the client: “What did you do in 2008/2009?”

Well, if you know their goals, assets, and anticipated longevity, the risk requirements and risk capacity are not hard to determine. It’s only risk tolerance at issue.

75% of that solution is education on 1) how capital markets work, 2) continual reminder you can only get 2 out of 3 (safety, liquidity or growth; well, I guess Bernie Madoff got all three, for a few people, for a while), and 3) getting them to turn off the financial porn.

The remaining 25% is personality. (I grabbed those percentages out of thin air, but you perhaps get the point.) Once the cake is baked it’s hard to un-bake it, so for really nervous nellies education may not do it. Some percentage have been educated but still are ready to jump off the ledge in a bind; that’s a matter of reminding them over, and over, and over… If you have the patience, you may keep that client.

I think the DiSC profile, or something similar, may be as good as FinaMetrica or Riskalyze. We might try to think of ourselves as therapists who get paid by AUM rather than the hour on the couch.

In my 32 years experience, most of the financial advice industry proceeds to identify the maximum pain one can bear (risk “tolerance”) and proceeds to create a target allocation designed to ultimately experience that pain, whether they need to or not. I always felt this was akin to identifying whether a person can “tolerate”

a second-degree burn and then proceeding to place their hand in a fire long enough to achieve it.

Wouldn’t it be more “prudent” to suggest as much investment risk as needed provided it isn’t more

than necessary? Wouldn’t it be “prudent” to suggest as little risk as possible so long as that it still permits the client to avoid consequences that they would consider more dreadful?

I for one do not think there is a formula or technique that will work effectively. Does it not make more sense to have a client understand the tradeoffs between what is important to the client and whether it is more painful to not achieve certain goals vs. taking on a bit more uncertainty?

Mr. and Mrs. client, you said you do not wish to take much investment risk. Therefore, here is a portfolio specially designed for you that will make sure your daughter is not able to attend the college of her dreams, simply because you have never been disabused of the notion that fluctuation is risk. So sign right here, and we will be on our way…

My 2 cents

Great Article Michael…as ususal.

Three things matter:

Need for growth (return)

Tolerance for loss

Capacity for loss

I use Riskalyze for tolerance and eMoney to compute the other two.

If the need is greater than tolerance and/or capacity, goals probably need to be revised.

It has seemed to me that regardless of the risk level that risk tolerance questionnaires determine is appropriate based on the answers to the questions, when the market drops 2% or 3% for 2 or more days in a row, clients get either upset or concerned or nervous. The ‘calculated” risk tolerance is often not the “real” risk tolerance. Investors also seem to be “willing” to accept more risk when the market’s are going up and less when they are going down. One of the best articles I read was Risky Business by Mitch Anthony. See http://www.fa-mag.com/news/risky-business-1898.html. Mitch starts his article with questions; 1. How much money can you handle losing before you start throwing up and selling your children’s electronics on eBay?

A. 0%-10%

B. 11%-30%

C. 31%-50%

2. Which statement best describes you?

A. I watch CNBC 12 hours a day.

B. I have my advisor’s number on speed dial but only call on 100-point dips or greater.

C. When the market is down, I take out home equity loans and invest more.

Yes, it’s a problem. It’s also one that I don’t think financial firms are motivated to solve. The risk tolerance questionnaires I’ve had to answer seemed to be more for the purpose of covering the firm by putting me on record as having risk tolerance than for actually measuring risk tolerance.

They all seemed designed to soft-pedal risk. For example, even after 2008-2009, they never seem to ask you anything about the possibility of a 50% drop in the stock market. It is much commoner to refer to the 37% decline that occurred during calendar year 2008. Why? Well, I think, obviously, because 37% seems much less intimidating–even if you’re financially literate–than 50%. But personally, the way I processed what was happening at the time was in terms of years of savings–how many years of patient retirement savings had just been shot to hell.

It’s all in the framing. It’s hard to know what’s objectively neutral, but all the questionnaires I’ve seen weren’t neutral at all–they were framed so as to make the risk seem less intimidating.

How about this: what do you think are the odds of a total financial collapse of the U.S.? That, too, is the way many people were looking at it in 2008-2009, I think. The problem wasn’t just the decline in dollars. It was that the chances of literally losing everything seemed to have climbed from, essentially zero, to, let’s say 10%.

Finally, the test do not seem to be designed to measure whether you have relatively increasing or decreasing risk aversion. Some people feel that as their wealth increases, they should take less risk, because “if you’ve won the game, why keep playing?” Others feel they should take more, because they now can afford to lose a bigger percentage and still be OK. The funny thing is that people always seem to believe that there is an objectively correct answer.

No it is not a problem I was one of the early adopters in the UK of a system developed by Antipodean friends .Fina metrica I have reviewed the risk profile each year with all my clients. The one observation I can clearly stay with authority is that of our clients over that period has been regularly consistent. We even carried out the exercise shortly after the 2008 crisis risk profile overall remain the same

Prior to using the risk profiling system assessing risk was a very scientific exercise here in the UK.It was either developed by asking a client what risk are they low, medium or high risk or asking them to measure their risk appetite by using numbers 1-5 or 1-10. Naturally, many of the clients I have dealt prior to risk profiling where I a “medium risk” , or “3” (if we used 1-5) or of “5” if we used 1-10

5 years ago I reviewed our whole investment strategy. Bearing in mind the academic evidence that asset allocation is a main driver overall performance we decided to concentrate on that area.

The whole objective of the exercise was how we could incorporate cash flow planning, risk profiling and finally suitable asset allocation easily understood by the client We wanted to do is give the client a better understanding of how the investment world works. Frankly, I was getting sick and tired of having meetings with the client bringing newspaper clippings of the funds are been highlighted and questioning why we had not selected such and such a funds, or sector in their portfolio. Financial planning, tax planning and other important issues went out the window and it was all about fund performance the next sectors to be in sectors to in and inevitably market timing.

I am now into my 5th year. At the start I explained clients we were changing our process in which the returns required to meet their goals and objectives within their and financial plan would the qualified and quantified by asset allocation.

Furthermore, that asset allocation will incorporate our discussion the finding from the risk Profile .

My first action employ a consultancy that specialise in top-down portfolio construction & management practices for both active and passive. They also provides economic data and comment on international capital markets. But were completely free from the influence of the marketing department which is quite often sent to the media as well.

With this company we have produced a detailed brochure that concentrates on the asset allocations I use as a template within the firm. This explains how the models both Strategic and Tactical have performed since the start of the decade.

The first paragraph within the introduction states that I think asset allocation is the most important influence not only on achieving your personal goals and objectives but on the investment returns required by the cash flow to ensure they are met and you can maintain your lifestyle

If they are a new client this is sent out to them prior to our 2nd meeting, the a existing client it is sent out as part of their renewal pack. Furthermore, I also decided that in house fund selection would stop and asked a number of Discretionary Fund Managers (DFMs) in the UK would they be willing to allow us to have control and influence on the asset allocation and they would then manage fund selection and pre-populate asset allocation models.

This I feel is the problem advisers are having the risk profiling process . The answer the DFM’s gave me was that they have their own allocation models.. All I have to do was map my risk profile finding with the their models. One even stated that only would it satisfy the regulators but the clients will be pleased with the outcome! .

That why I feel that Robo advice will not be the panacea it is made out to be. To satisfy the requirements of the regulators the whole process and marketing main emphasis is on risk profiling. The client has not got a clue about risk never mind as outlined on the comment below understanding the questions

May I suggest that your approach should be next time you have a client meeting and they have completed the risk profile. Instead of concentrating on the findings from the risk profile concentrate instead on the asset allocation If you have access to Morningstar or any other investment analysis system this should be easy to summaries. If not use a spread sheet or could always pick up the phone and ask the investment provider for break down asset allocation and it’s performance. If my experience is anything to go by that question will not be answered.

If you use a cash flow planning I am sure you’ll be up to calculate what the overall return needs to be. I found over the last 5 years that when I inform the client of global target return required to meet their goals and then present the asset allocation to confirm that stated investment return in the cash flow. They understand it far better than discussing the findings from the risk profile.. I use the risk profile findings to quantify that the selected asset allocation My experience has been that my clients get a better understanding of the investment process and the risks they have to take in order to meet goals and objectives outlined within their financial plan.

In repect to why client don’t understand the questions I have found that if you explain to the clients that there are no longer the right answers within the questionnaire. The questions are designed with 3 objectives in mind.

To gather information on your past experience when investing

to gather information on your for future expectations

Finally to put you in situations where you have to make a decision on investment proposition.

I find that in clients understand are prepared to fill in all 25 questions.

Very good article. At the end of the day, we are trying to measure risk tolerance for humans. We really have not figured out how our brain processes emotions, memories. May be more understanding of human behavior in the next 100 years will allow us to build a better tool. Prior events really alter our perspective on risk. How can you design something that will work the day before and after an event like Sept 11.

Our inability to build a perfect tool is one reason I believe that the robo revolution will eventually reach a saturation point. Good advisors can compensate for a lack of questionaire

Michael,

Have you considered changing the frame of this piece to be directed at consumers rather than at advisors so that we might share it with clients or on social media? This does such a great job of describing the nuances of how difficult it is at coming up with an appropriate asset allocation and the incalculable role of an experienced advisor in the process.

You are correct that the current questionnaires dance around the point. It is not that difficult to explain to a client that all investing has risks some of which may not be foreseeable and that some of their money may be lost. Simply asking a client “if the worst happens, how much are you willing to lose?” is a good way to do it. Ascertain that amount, put in stop losses and away you go.

After considering the issue from seveal angles, that’s the exact question I have settled on, it’s what I ask myself (and ask myself, and ask myself…).

I wonder, would it ever make sense to ask ‘how much return are you willing to forego’? i.e. if the general market is up 25% and the client is up 15%, this may be the result of an appropriate risk/return profile. But, if it’s due to high fees, inappropriate allocation, etc; and the client needs near market returns to hit their long term savings goals, I think most clients feel good because they see the 15%, but are unaware of the 25% and of the long term implications. Asking the ‘forego’ question might put the client in a more balanced frame of mind?

Michael – this is a very good summary on the state of play regarding risk tolerance questionnaires. You have articulated very well the framework that is needed to distinguish between tolerance, capacity and perceptions. When advisors use Financial DNA (www.financialdna.com) we make it very clear that they need to address tolerance, capacity and perceptions and we provide them the structured framework to do it. There is also the issue of how the risk profile is used in goals-based planning where the client has a portfolio designed to achieve buckets of goals. So, there may be multiple risk profiles applied given there are different goals. Nevertheless, the risk tolerance of the client must be known and the framework you outline applied.

Many advisors do think that the risk tolerance can be determined by observation. However, this will never be objective as it relies on the advisors perception of the client in the current circumstances which could also be influenced by their own risk profile and biases. Very often the client will “eat” the risk profile of the client. Also, not using a validated psychometric risk profiling process means that the advisor does not have a consistent process for handling the risk conversation with the client, and it will lead to different results across the firm and potentially with the same client. While the regulations do not yet say a validated psychometric process must be used, that is what is required if the firm wants to have a robust process that will give them a better chance of dealing with costly complaints. Of course, as you point out it is not just the tool itself but also the planners behavior and skill in deploying the tool which is important.

Some advisors will also say that they do not want to bother the client with more paperwork so they do not have them complete a risk questionnaire – but what we have found is that using one demonstrates the planning process is client centered and also the client is more engaged because they participated. So, there is a revenue benefit and overall a service quality enhancement.

Now the discussion gets down to what is the design of the risk tolerance questionnaire – “right data in, right data out”. You are right (as is Plan Plus), most tools are inherently flawed for many reasons and many purport to be something they are not. The questionnaire structure is so important to the outcome, and must follow an accepted psychometric model. Our view is that all of the risk profiles (even the validated ones) use situational based questions by their very nature – that is the client could respond to the questions differently at different times depending on their current attitudes, feelings, perceptions, education etc. While this is good to know, it does not tell you the emotional state of the client when they are under pressure and how they will be “hard-wired” to instinctively make decisions when under pressure – or as Daniel Kahneman says what their “Level 1” automatic decision-making style will be. Unless you know the Level 1 style it is impossible to build a long term portfolio for the client as it will not be emotionally compatible. So, the questionnaire has to be designed to uncover the Level 1 behavior which is actually free from situational bias. This has been the premise of the Financial DNA design and the results are well known to be accurate. Do you want the results to be accurate as the foundation of a robust process, or would you rather something that is soft and pretty which will help tick the box but is flimsy? This is the choice.

The aspect that is missed in all this is that risk tolerance is only 1 dimension of a clients financial personality. There are so many more dimensions that need to be known which is where the broader field of behavioral finance fits in to bring understanding to all the decision-making biases of the client and the advisor. If these are not understood and there is not communication re-framing around these biases then this will cause risk of itself. So, the risk discussion is not complete without knowing the clients complete set of behavioral biases and knowing how to communicate on the clients terms. This is why understanding the clients complete financial personality is so important and the questionnaire design must achieve this.

One thing for sure is that the regulatory process will not go backwards and certainly in today’s demanding and complex world costly client complaints will not go down. But, on the positive side, those advisors who are investing in building client centered processes which are also compliant are doing much better financially. So, why not invest in a stronger “Know Your Client” process as what is good for the client will be much better for you too?

I concur with Hugh. I have been using the Behavioral DNA profile client discovery process for several years and the Financial Personality profile provides in depth “know your client” and their propensity for risk that will assist an advisor design a appropriate asset allocation.

Michael – good job in taking a 127 page research report and condensing down to a Blog post. For clarity the research was sponsored by the Investor Advisory Panel of the Ontario Securities Commission. For those interested in the full report see http://www.osc.gov.on.ca/en/Investors_nr_20151112_iap-releases-research-risk-profiling.htm

As a DIY investor, I found this fascinating, and I think the core issue is that people have a limited perception of their risks. It’s hard to understand the point without the background, so here’s where I’m coming from:

I have a high tolerance for “risk”, defined as volatility. However, risk, is so much more than mere volatility, as you note. Return is just a form of risk – too little, and you don’t meet your goals. Return risk takes many forms from market risk to inflation risk to duration risk etc etc. High tolerance for volatility doesn’t mean that I like to see the value of my portfolio decline (although sometimes I do – when I think it’s a good opportunity to rebalance, for example.) I suspect every client goes through a risk evolution, if they are “invested” in the process.

When younger, I was usually 100% in equities; I never had more than 10% in bonds. The dot.com crash was painful, but I rode it out entirely, not buying or selling anything. However, I also became obsessed with finding better risk/reward trade-offs and understanding when the ‘big drawdown’ was likely (not worrying about minor declines). In late 2007 I was convinced that market risk was very high. I sold 10% of my equities (again had no bond component in portfolio) each month into 2008, figuring if I turned out to be wrong, I could reverse direction with modest damage. Lost 13% that year, so I called it a one time success, and started buying again in 2009, 10% a month. I violated the buy and hold tenet, which is what risk questionnaires are largely trying to prevent, but did so from a considered viewpoint with an understanding of at least some of the risk of doing so.

My approach worked, but the obvious flaw is repeatability – I had no ‘rules’ to follow regarding exit or entry, and concluded that this approach was also ‘risky’ from that standpoint, & therefore unsatisfactory. I did spend a little time on some general timing approaches, but my results suggested that it was a lot of work for little benefit, mostly just trading one set of risks for another.

Since then I’ve spent a lot of time absorbing portfolio theory. I now use a portfolio that’s 72/28 and would have handled the dot.com crash well, would have lost about 20% in 2008, and would have outstripped my mostly 100% equity portfolio over the past 15 years by a healthy amount, I still poke at the portfolio, trying to understand the risk/reward implications of TIPS and even of some alternative strategies (with trepidation), the goal being to consider all forms of risk I can conceive of – returns that are too low, potential black swan events, interest rate/duration risk, extreme volatility (which I believe can reduce safe levels of retirement withdrawls, regardless of return).

After all of this, it seems to me that questionnaires are designed to answer one facet of the risk question, and evidence seems to be that the results are mixed, so it’s good to tinker with the form and content to try to get it right. However, I wonder if that approach has an inherent shortcoming, in that the real question may be whether the client has an appropriate appreciation for all of the risks they face, and how those risks interact? I suspect the answer to that question will weight their reaction to simple market drawdowns.

John,

I think the role of whether the client has an appropriate appreciation of the risks they face is absolutely crucial. But that’s technically not a matter of risk TOLERANCE. That’s the dimension of risk perception – how are the portfolio’s risks PERCEIVED (including whether they’re being perceived accurately/correctly/at all).

Both matter, but they’re different dimensions. A risk-tolerant individual might still sell out of stocks if they mis-perceive the risk, and a risk-intolerant individual might own too much in stocks if they mis-perceive the risk. But that’s not a tolerance issue itself, but a misperception issue that’s causing them to not properly match the correct portfolio TO their tolerance.

– Michael

The big problem as I see it, is that the industry continues to treat risk profiling as an input, instead of as an output. The difference is significant and poorly understood. Risk “tolerance” is the question of “what might you have to do?” And thus in the context of a financial plan, it is the question of the tolerance for taking certain actions, after the fact. For example, if you have to take a pay cut, or want to take a sabbatical, or if you lose your job for a period of time, or if your portfolio falls in value by 20%, or if you have an unplanned major expenditure, in each case the impact is that you will fall off-track to achieve your goals. “Tolerance” is thus the question of what are you prepared to do, to get back on track? Are you prepared to: defer your retirement? Or bring forth the sale of an asset (e.g. downsize your home earlier than planned)? Or increase your current savings contributions?…or a combination of these things. If to get back on track you need to increase present savings by (say) 110% of your income then that is a test of ‘capacity’ – you might have the tolerance to do such a thing (if it were possible) but clearly no capacity. Likewise, deferring your retirement may be an action you are prepared to take but if getting back on track means deferring retirement until you are aged 95, then it becomes a test of capacity. Capacity is thus also an output – something that can only be truly determined after consideration of the client’s present financial situation, their ability to work, earn, save and invest and their goals and objectives. The determination of a client’s risk tolerance and risk capacity are thus outputs of the financial plan, not inputs.

Risk tolerance questionnaires suffer from 3 problems. 1) Their overly technical nature; 2) Response bias, which results in an investor responding differently when stressed; 3) Risk tolerance vs risk capacity is not well-understood by clients.

A 2012 study of risk tolerance questionnaires showed that many products failed to accurately predict client behavior when they are under pressure. DNA behavior International, an Atlanta-based firm founded by Hugh Massie, has developed a very different take on the traditional risk tolerance questionnaire.

http://bit.ly/WMToday_FinancialDNA

I agree with the need for 1) Capacity (objective) 2) Tolerance (subjective) and 3) Perception (subjective) to result in the most accurate risk profile questionnaire score. However I have yet to see anyone determine any sort of thesis on how to weight these (3) types of questions in the scoring mechanism (e.g. 1/3, 1/3, 1/3 or 50% capacity, 25% Tolerance, 25% Perception)?