Executive Summary

Many financial advisors are involved in providing financial education, from delivering a financial literacy course in schools, or lending our expertise to create financial education resources. An activity that for us is no doubt driven by seeing first-hand the damage that can be caused by financial illiteracy and making ignorant financial decisions.

Yet a recent meta-analysis of over 200 prior studies on financial literacy programs finds that providing long-term financial education is remarkably ineffective. In fact, the researchers found that interventions to improve financial literacy explain a statistically significant but practically irrelevant 0.1% of subsequent financial behaviors.

The problem appears to be driven primarily by the fact that, as with so much of our education, concepts and skills that we don’t use can quickly atrophy. Which means trying to make children financially literate when they’re in school may still result in them to grow up and struggle with financial illiteracy as adults.

So what’s the alternative? An approach called just-in-time training, which aims to provide financial education at its moment of maximal relevance and usefulness – when the financial decision itself arises, and the education can be immediately applied.

The caveat, though, is that the likely provider of financial education in such circumstances would be the financial services product provider, who may have an untenable conflict of interest against helping someone to become financially literate, if doing so might actually talk them out of buying the company’s product. Or alternatively, there’s a risk that the financial services company could frame the financial choices in a manner that “nudges” the consumer towards a not-necessarily-beneficial outcome.

Yet arguably, this may be a perfect role for financial advisors to fill, particularly as financial advice increasingly shifts from product sales to bona fide independent third-party advice. For instance, just as drug companies can market their products to consumers, but still have to recommend “consult a doctor before taking this drug”, so too might financial services product providers be required to direct consumers to consult an (independent) financial advisor before buying at least the more complex financial services products (while “robo-financial-education” technology solutions might help to step in for simpler product and financial decision education). And financial advisors can also help consumers navigate the often emotional and not-always-rational aspects of financial decision making as well.

Which raises the question: while financial advisors have historically supported financial literacy programs on a pro bono basis, should a key element of the financial planning business model include not only offering financial advice and helping consumers to evaluate their financial trade-offs and decisions, but also as a financial education provider of just-in-time training on key financial concepts as well?

Financial Illiteracy And The Ineffectiveness Of Financial Education Programs

There’s little doubt that the financial world is getting more complex. The past several decades have witnessed an explosion of increasingly sophisticated choices in everything from borrowing options (from credit cards to peer-to-peer lending to payday loans and various forms of exotic mortgages) to savings and investment opportunities (from mutual funds and ETFs to the plethora of tax-preferenced accounts including IRAs, 401(k)s, 529 plans, HSAs, and more) to the broad impact of the infamous (yet opaque) credit score.

The growth of financial complexity in turn requires an increase in the depth and breadth of financial knowledge and sophistication for consumers to navigate these various financial products and services. Yet it appears in practice that we’re failing to keep up, as evidenced by everything from rising levels of financial stress amongst consumers, to the sad fact that the number of bankruptcies grew 5-fold between 1980 and 2005.

The struggle to keep up with financial complexity, coupled with the fact that financial life skills are rarely taught in school, has led to significant growth in programs that provide financial education – from adult interventions to financial literacy programs for middle- and high-school children – in an effort to raise the public’s financial literacy level, at a cost that some estimate could collectively be billions of dollars. Yet despite the cost, it’s hard to argue with the virtues of being better educated – teaching key financial concepts, and how to make better short-term and long-term financial decisions – to deal with an increasingly challenging financial environment.

Except that, as it turns out, it’s not clear that our efforts at solving financial illiteracy are actually yielding material results. In a recent meta-analysis of over 200 prior studies on financial literacy programs, conducted by Daniel Fernandes, John Lynch, and Richard Netemeyer, and entitled “Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Downstream Financial Behaviors”, the researchers found that interventions to improve financial literacy explain a statistically significant but practically irrelevant 0.1% of subsequent financial behaviors.

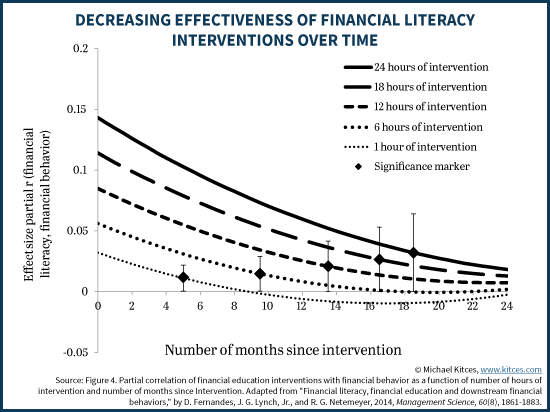

The problem appears to be driven primarily by the fact that – like so much formal education – the knowledge we don’t use will atrophy over time. Just as few likely remember the details they learned in school about Shakespeare’s plays or the Battle of Gettysburg (if they didn’t end out with jobs that deal with those topics on a regular basis), so too do people forget much of the important detail associated with financial education over time. In fact, the researchers found that within a year, the benefits of a 6-hour financial education program were no longer statistically significant (i.e., no longer distinguishable as having any positive impact at all!); after about 18 months, the benefits of even 24 hours of focused financial literacy programs have typically vanished.

The situation likely isn’t helped by the reality that it’s difficult for many to connect classroom learning to real-world applications that may only be relevant years later. Not to mention that many financial decisions have a significant emotional component, which means we may not necessarily be thinking with the rational financially literate part of our brains when the time for a key financial decision actually comes!

In addition, the researchers found that even the overall correlation between being financially literate and effective financial behaviors (e.g., having an emergency savings account, knowing what you need for retirement, and having a good credit score) may actually be attributable to underlying personal traits, including an individual’s natural propensity to plan for the future, willingness to take at least prudent investment risks, and who have confidence in their ability to search out and find information when it’s needed. Which in turn means that those who exhibit positive financial behaviors and have strong financial literacy may score well in both because they’re simply already naturally inclined towards doing both. (Though technically the research is not clear on the causative direction of the relationship; it’s also possible that teaching financial literacy positively impacts these traits, which in turn help lead to better financial behaviors.)

Nonetheless, the fact that some of the benefits of financial education may be driven by certain natural traits that favor financial literacy in the first place, and that the benefits of a financial education intervention (in the absence of an immediate opportunity to apply it) tends to deteriorate within a year or two, suggests that it may be time for an alternative approach to financial education that more directly pairs the financial education to the individual in their moment of need (before it has time to be forgotten!).

Just-In-Time Financial Education To Improve Financial Behaviors

The idea of “Just-In-Time” financial education is that rather than trying to intervene early to improve financial literacy – when the education may not be relevant and is likely to decay (thus being forgotten by the time it’s actually need) - it should instead be delivered at the moment that the financial choice itself is presented.

With just-in-time training, the financial education is certain to be relevant (since it would be targeted accordingly to begin with), and doesn’t risk being forgotten by the time it’s actually necessary (because it’s immediately applicable). In addition, just-in-time financial education can be delivered far more efficiently – rather than provide several days of education with the hopes that “something” is retained a year or few later when it actually matters, a mere hour or less of targeted education may be able to have a similar impact, which provides the same benefit but a small fraction of the time and labor cost for the financial education itself.

For instance, perhaps the best time to teach about the differences between fixed and adjustable-rate mortgages and how much mortgage is affordable is not in a high-school or college financial literacy class, but at the point someone is actually getting ready to buy a house and actually needs a mortgage. Similarly, financial education about how credit cards work can be provided at the time someone tries to open their (first) credit card, the difference between checking and savings accounts can be offered when someone goes to the bank to open an account, and just-in-time financial education can even provide contextually relevant but more nuanced educational opportunities (e.g., Betterment’s “Tax Impact Preview” educational warning on the capital gains tax consequences of changing a portfolio allocation at the moment someone logs into the app to make that change).

Notably, the point of just-in-time education is to provide more than just an explanation of a product’s features and benefits, and/or “educational disclosure” in the fine print about how it works. The purpose is to provide just-in-time financial literacy skills that allow someone to have better context about the decision itself – for instance, not just about how payday loans work, but also their alternatives, and not just about how the mortgage works, but also how much house and mortgage is prudent to take on in the first place. Signing up for a 401(k) plan wouldn’t just provide a list of investment choices and disclosures about the expenses and performance, but also more general financial education about how stocks and bonds work, the impact of long-term compounding returns, and the tax treatment of 401(k) plans.

Unfortunately, though, a significant problem with the idea of just-in-time financial education is that it will often rely on the company providing the product or service to deliver it – and companies selling financial products don’t exactly have a positive financial incentive to educate someone that the product might actually not be the best thing for them after all! And we know from the growing body of research on “choice architecture” that how choices are presented can greatly impact the financial decision that is ultimately made. Which means financial services companies could potentially undermine or obfuscate the relevance of just-in-time financial education by how the education is framed and delivered, particularly if the “best” choice really should be to buy a completely different alternative product, or no product at all. And of course, some products are so complex that it may not be feasible to get sufficiently educated to make a well-informed decision based only on just-in-time education alone.

The Role Of Financial Advisors And Technology For Just-In-Time Financial Literacy Training

The fundamental conflict of interest for a product provider to offer just-in-time education that could turn out to undermine the sale of the company’s product raises interesting questions about the role of (independent) financial advisors.

After all, arguably financial planning done well has a heavy component of providing financial education, helping people consider trade-offs and long-term ramifications to their financial decisions, which are the exact issues that one would hope be considered when making significant financial choices. And the training and expertise of financial advisors – at least those who have voluntary certifications beyond the basic regulatory licenses – leaves them well positioned to help consumers navigate, particularly the most complex financial products and decisions.

In other words, perhaps just as drug companies can market to the public but ultimately direct consumers to “consult your doctor before taking this drug”, so too might the implementation of just-in-time financial education for consumers entail the use of a financial advisor. For instance, consumers might be advised to consult an independent financial advisor before purchasing a complex annuity product, or allocating money to an illiquid hedge fund, or taking on an exotic mortgage (or any mortgage at all). In point of fact, the government has already adopted a version of this approach for reverse mortgages, which requires the completion of a 1-hour counseling session to get educated about both the reverse mortgage and its alternatives. (Though sadly, financial advisors – even those who are CFP certificants – do not even qualify as HECM reverse mortgage counselors!)

Notably, a key requirement for the effective use of financial advisors as a deliverer of just-in-time financial education (particularly for consumers who otherwise lack financial literacy and would rely heavily on the expertise of the advisor) is that the financial advisor actually operate under a fiduciary standard as an independent advisor. If the financial advisor was still functioning as a salesperson for the product company, at the same time he/she is supposed to be giving financial education and advice, the relationship risks being tainted by the same conflict of interest that could undermine other seller-provided just-in-time financial education.

Of course, in some situations, the financial need or product involved may not be so complex that it requires a full consultation with a financial advisor to begin with. In these scenarios, technology solutions may help to fill the void as well. This could include objective third-party tools like Saving For College’s 529 Comparison solution or FeeX to evaluate investment costs, and may eventually evolve to the point that the software monitors an individual’s entire financial picture (e.g., using account aggregation tools) and uses algorithms to determine when relevant financial education should be presented (such as offering education about the value of an emergency savings account for someone who doesn’t have one, or the consequences of credit card interest for someone who’s only making minimum payments). In essence, the financial technology solution becomes a form of “robo-financial-educator” to both identify just-in-time financial education opportunities, and then deliver them.

Still, even financial education through technology will be limited for the foreseeable future, in a world where often the biggest financial challenges are behavioral, not merely informational and educational. And in this context, arguably given the way humans are hard-wired, it will be a long time before we’re willing to have a computer tell us that we’re being irrational (even if we are). And even then, sometimes it may still take the empathy of another human being to have a conversation and help us explore the possibilities and figure out what our goals are in the first place. In other words, the computer may be able to answer our questions and provide education (and identify those educational opportunities), but at least given today’s technology, it takes another human being to help us realize the questions and issues we aren’t even asking about.

Ultimately, the optimal solutions to aid in just-in-time financial education and better decision-making will likely entail both the use of technology tools and human financial advisors – as we’re discovering is the case in the world of “robo-advisors” as well, where technology can make some parts of the process very efficient, but the necessary-yet-often-irrational behavioral challenges of individuals are still better suited to the financial advisor as counselor and educator (though not salesperson).

Nonetheless, the key point remains that as the word gets more and more complex, the long-term solution really may not be trying to make everyone financially literate – given what are already somewhat dismal results for the effectiveness of such financial literacy programs and initiatives. Instead, the solution may be more about providing a combination of just-in-time financial education when it matters most, and the assistance of financial advisors as both experts and counselors to guide consumers through the decisions that are too complex, or too behaviorally driven, to be solved by information and education alone. Though obviously, this still doesn’t resolve the broader societal challenges about whether everyone has a sufficient opportunity to advance their financial situation in the first place, whether financially literate or not!

So what do you think? Is it time to re-evaluate the benefits of financial literacy programs? Could financial advisors have a different role to play, as a provider of just-in-time training for financial education? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Totally agree with you on this, Michael!

I’ve participated in several programs to deliver financial literacy to high school students. Although the students are learning, I have always felt that all info is more relevant when one is receiving a paycheck. Just in time is even better. My next move is to target certain age groups for specific educational programs. First step: 40-60 year olds on retirement savings goals, are they enough? This seems consistent with your post, and I find that pretty cool!

Of course! Just as 90% of the time you spend with a good doctor, or lawyer, will be about learning, the same will naturally apply to time spent with a financial fiduciary. Well done, Michael. Time to re-think public policies and initiatives aimed at delivering financial education at the wrong time, and time for professional financial planners to acknowledge how much of what they do and get paid for is delivering truly effective, “just in time” financial capability.

Thanks for the thoughtful points Michael. I mostly agree, and think the way a lot of financial literacy programs are designed and delivered — structured or otherwise — miss the mark. And as you say, the stats back it up.

I believe the focus should be on teaching the few fundamentals that do not change (e.g. compound interest); learning how to be self-aware so people are able to identify when they need help; how to find and evaluate good info from bad (e.g. conflicts of interest or dumb advice from friends …or salespeople); how to identify poor behaviours and modify them. All within the context of the stuff that matters to them right now.

I’m working on a side project at the moment, aimed at doing this for school-aged kids. We’ll see whether it’s effective or not, but I reckon it’s worth a good Aussie go.

Michael,

Well done.

Thanks for the references to prior studies about the effectiveness of financial literacy programs and about the vested interests of advisors, product providers, etc. Based on your article, I will try to give people actionable advice that keeps their skills sharp. Use it or lose it.

I hope that you continue your research on how incentives affect advice. My main interest is this: How can fee-based fiduciaries be truly objective while still running a business and earning a living?

Or is it Vanguard for everyone?

Thanks again,

Rob

The problem could also be the poor quality of the financial literacy programs.

In fact, could you pls share some examples of what you consider to be good programs

I founded a non-profit, Next Gen Personal Finance (www.nextgenpersonalfinance.org), to make up for many of the shortcomings that previous commenters have made. Our curriculum emphasizes critical thinking, decision-making, web research skills and making it relevant to high schoolers. My feeling on personal finance education is that it should be taught in schools AND just-in-time. Besides, who can think of a more important decision that young people face today than the one they make about college and how they are going to pay for it.

Hi –

Can anyone recommend a web based platform for providing financial literacy advice to 401k plan participants?

Thanks

Hi Michael,

I have a similar question/comment as Hansi… how does one evaluate the quality of the financial education programs that are represented in the study? From my experience looking at the financial education landscape, there is a big opportunity to raise the bar.

The idea of just in time training is great, but I hope we don’t encourage throwing the baby out with the bath water.

From my experience, young people have BIG dreams, but often don’t know the next step to take to bridge the gap between where they are and where they want to be. A lot of information is presented in a way that can seem irrelevant or unattainable. The result of that can be that they disengage at a critical time. Once someone has taken on too much debt and credit scores drop, it can become a snowball effect that leads to delayed savings/investments, etc. I still see financial education as one of many components to provide a preventive measure to these issues.

We have to stop encouraging programs that are focused on ‘who wants to be a millionaire’, just skip Starbucks and you’ll be fine, all debt is always bad, everyone wants a McMansion with a sports car out front, etc., and start the conversation the way we do with our financial planning clients:

What are your goals and priorities?

What are the implications to your goals and priorities if you’re taking on too much consumer/auto/home/student loan debt? What can be achieved if they’re in check?

How can you protect and grow your credit score as a young person and WHY it’s important.

These are the conversations that are meaningful and empowering.

This topic is near and dear to my heart because it’s something I’ve been working on through Common Cents Financial Literacy for the last 10 years. We focus on ages 16-22 because that’s when young people start to make independent financial decisions and habits that follow them for years to come. Our program is far from perfect and ever-evolving, but I’d hate to see everything lumped together as an ineffective waste of time. How do we make it better?

Thanks for bringing this up!

You guys who are doing binary options trading and making less than $2000 a day have to do what I’m doing. Check out this automated binary options that I’m using http://rurl.us/18hWo

Thank you Michael for taking the time to write such a great piece of informative information!! Financial literacy knowledge doesn’t match reality, nowadays it’s very difficult for beginners to learn real-world knowledge without the strategies. The optimal solutions to financial literacy courses and better decision-making will likely the use of technology and expert financial advisors.

Nice & Informative Blog! Everyone should be financially literate since it promotes independence and financial stability. With the help of this, one will be able to manage a budget, see the difference between wants and necessities, save money, pay their bills on time, and make retirement plans. But having a financial advisor to guide you in each step is very important. Thanks for sharing this informative blog.