Executive Summary

In recent years, numerous software solutions have sprung up that aim to automate the process of tax-loss harvesting. Both retail-focused robo-advisors and advisor-focused TAMPs have begun to offer automated tax-loss harvesting, which – by systematically checking for losses to harvest, typically on a daily basis – purports to increase investors’ after-tax returns by 1% or more.

But what the providers of automated tax-loss harvesting often don’t mention is that the actual value of tax-loss harvesting depends highly on an individual’s own tax circumstances. The 1%+ added value of automated tax-loss harvesting may be achievable in some ‘ideal’ cases, such as an investor who frequently contributes to their portfolio, has short-term losses to offset, and/or has many individual security holdings. But in other cases where those factors aren’t present, the added value of tax-loss harvesting is often much lower – which suggests that the value of automated tax-loss harvesting is less about the automation itself, and more about capturing losses under the right circumstances when the factor(s) that enhance the value of losses are present.

Unfortunately, much of the technology dedicated to automated tax-loss harvesting fails to consider the individual tax circumstances that drive most of the true value of harvesting losses, and instead focuses on the portfolio-management aspect of efficiently capturing as many losses as possible. Which can be a problem when such technology advertises itself as an all-in-one solution for tax-loss harvesting with no additional effort required by the investor or advisor because, in reality, not all investors may benefit from tax-loss harvesting, and the crucial information necessary to decide whether an investor is (or isn’t) a good candidate for tax-loss harvesting is often the very information that automated tax-loss harvesting software fails to capture.

While there still can be uses for technology that automatically harvests losses – such as in the occasional circumstances where it really is beneficial to harvest as many losses as possible – many investors may be able to realize nearly the same value by harvesting losses tactically (that is, by recognizing when their circumstances might be beneficial for tax-loss harvesting, and harvesting losses only when those circumstances occur). And when factoring in the fees charged by those technology platforms, the value of such ‘tactical’ tax-loss harvesting might exceed the value the investor would have realized by relying on a technology solution to do it automatically!

Ultimately, the key point is that tax-loss harvesting is a tax planning strategy and not (just) a portfolio management strategy. What matters is not simply the amount of losses the investor is able to harvest – which most technology seeks to maximize – but that they are harvested when the investor is able to benefit the most from them. In this light, it may be worth spending a little extra time on the tax planning side before handing the process over to automation, to ensure that the losses harvested will be truly valuable in the long run.

Tax-loss harvesting is a method used to generate tax savings by deducting a taxpayer’s capital losses against their income from capital gains. And while it has been an available tax strategy since capital gains taxes were first enacted in the U.S. in 1913, it wasn’t until around the shift from the 20th to the 21st century that it became widespread among financial advisors and their clients.

A combination of factors that reduced the costs and streamlined the process of tax-loss harvesting led to its rise in popularity. Online brokerage platforms made it possible to identify portfolio positions with unrealized capital losses in real time without waiting for a statement to arrive in the mail. Reductions in trading commissions via low-cost broker-dealers brought down the costs of selling and buying securities, which had previously created substantial performance drag and, as a result, had reduced the potential value of harvesting losses.

Additionally, the proliferation of low-cost, index-tracking mutual funds and ETFs made it far easier to find substitute securities to replace those sold at a loss than ever before, as in the previous era, finding a stock or actively-managed fund whose performance would track closely with the original investment was much more difficult.

Technology developments in the early 21st century lowered the barriers to tax-loss harvesting even further. For example, portfolio rebalancing software like iRebal incorporated tax-loss harvesting capabilities into its portfolio management tools, allowing advisors to quickly identify the optimal tax lots to sell and to check for potential wash sales (i.e., a ‘substantially identical’ security purchased in a taxpayer’s taxable or retirement accounts within 30 days before or after the original security was sold for a loss) that would cause a loss to be disallowed.

Despite the improvements in technology, though, these solutions still required an advisor to manually review the trading recommendations and execute the trades themselves to harvest losses. And while doing this for any one client may not take very long, repeating the process across an entire client base of 50 to 100 clients (or more) can be enormously time-consuming.

As a result, tax-loss harvesting was often done only once per year, often near year-end. Which, while easier to systematize, was hardly an optimal way to harvest losses, since this method could only realize losses that existed at that particular time of year – ignoring declines that occurred near the beginning of the year (but subsequently recovered over the remainder of the year).

The Rise Of Automated Tax-Loss Harvesting

With the burgeoning improvements in financial planning technology tools over the past few decades, the landscape of tax-loss harvesting technology has undergone another sea change. A growing number of fintech vendors – including retail robo-advisors like Betterment and Wealthfront, as well as Turnkey Asset Management Programs (TAMPs) and direct-indexing providers like Parametric and Orion (who specifically target financial advisors) – offer automated tax-loss harvesting, using algorithms to detect tax-loss-harvesting opportunities and making the subsequent trades without any human review. By automating these steps, the software platforms are able to systematically check for tax-loss harvesting opportunities far more frequently than human advisors can, with many platforms checking daily instead of just a few times (or less) per year.

Beyond the time savings, providers of automated tax-loss harvesting also describe the process as a way to enhance after-tax portfolio returns. For example, Wealthfront claims that their typical customer has achieved a median benefit of 4.7 times its annual 0.25% management fee, equal to 1.175%, from tax-loss harvesting alone – which greatly exceeds other estimates that show the typical long-term benefits of tax-loss harvesting to be much more modest (in the 0.2%–0.4% range).

At first glance, taking advantage of a solution that can deliver more than a whole percentage point of excess return per year – completely automatically, with no additional back-office burden on the advisor – might seem like a no-brainer. But does the automated approach really boost the tax-saving potential of tax-loss harvesting so much as to overcome the associated platform fees (which can range anywhere from 25bps for many retail robo-advisors to 75bps or more for some TAMPs)?

Why The Claims Of Automated Tax-Loss Harvesters Don’t Always Hold Up

A closer look at the claims made by automated platforms shows that, in calculating the value of their services, they often rely on best-case assumptions that are unlikely to apply to many investors and that real-life benefits are likely to be much more modest.

For example, the Wealthfront claim of a 1.175% annual tax benefit only accounts for the upfront tax deduction that is captured from harvesting losses, ignoring the fact that tax-loss harvesting creates higher capital gains in the future by lowering the cost basis of the portfolio. Unless those future gains can be realized at 0% capital gains rates, or otherwise wiped away by donating the security to a qualified charitable organization or holding it until death to leave to one’s heirs with a stepped-up basis, the initial tax savings of harvesting losses could be partially or entirely offset – or even exceeded – by the future tax liability. In other words, the upfront tax savings can come at the cost of higher future taxes, which would make it much less of a ‘benefit’ than Wealthfront claims.

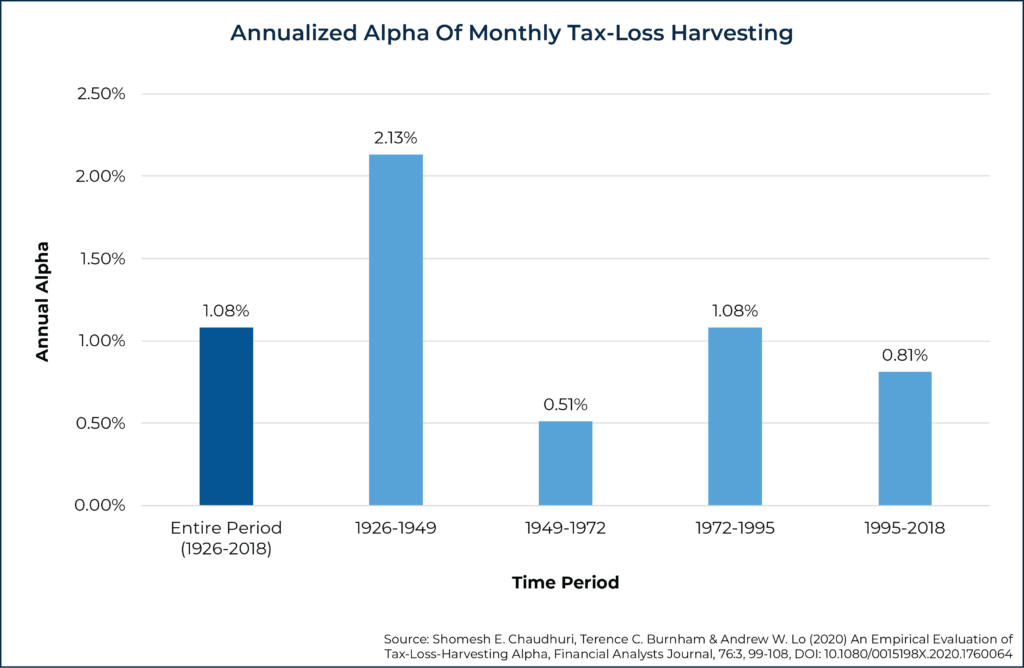

What is the true value of automated tax-loss harvesting? There is some empirical research on the subject from a 2020 Financial Analysts Journal (FAJ) paper by Shomesh Chaudhuri, Terence Burnham, and Andrew Lo. The research paper’s authors used historical U.S. stock market returns from 1926 to 2018 to test how a monthly systematic tax-loss harvesting strategy (i.e., selling each tax lot that is in a loss position at the start of each month and reinvesting the proceeds) would impact a portfolio compared with a benchmark portfolio that wasn’t tax-loss harvested. The researchers found that tax-loss harvesting would have yielded an average 1.08% of annual tax alpha compared to the non-tax-loss-harvested benchmark portfolio over the whole time period.

At first glance, this seems like an open-and-shut case in favor of tax-loss harvesting whenever possible, especially given that none of their scenarios produced a negative value for tax-loss harvesting. But a closer look at the paper shows that their numbers rely on a lot of favorable assumptions that might not apply to a sizeable number of investors.

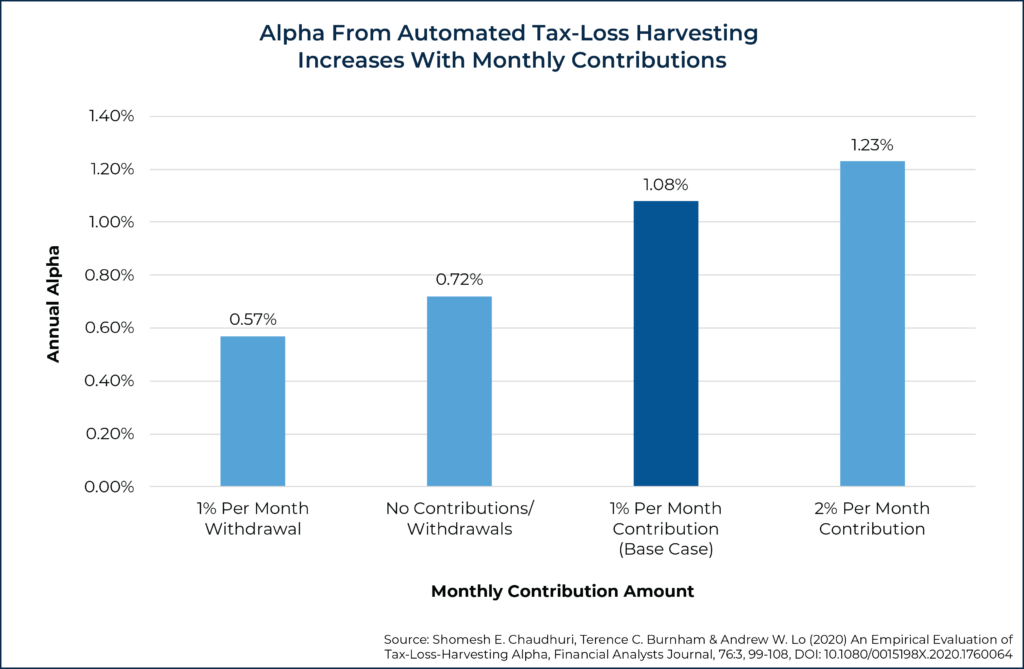

First, the paper’s ‘base case’ scenario (the one that produces a 1.08% tax alpha) assumes that the investor is making recurring monthly contributions to their portfolio. The benefits of tax-loss harvesting are likely to be greater for these investors compared to those who are regularly tax-loss harvesting but making no contributions, or those who are actively withdrawing from their portfolio. The main reason for this is that investors who don’t make regular contributions tend to eventually run out of opportunities to harvest losses: As markets (and portfolio values) increase over time, so do the embedded gains in the portfolio, and the more the embedded gains increase the more extreme (and therefore unlikely) of a market drop would be required to actually produce a capital loss. Contributing to the portfolio on a recurring basis, as is assumed in the FAJ paper, adds new higher-basis assets that create a continuous supply of potential losses to harvest.

When the researchers ran scenarios where the hypothetical investor didn’t regularly contribute to their portfolio, the annualized alpha from tax-loss harvesting dropped by one-third, from 1.08% in the base case (where the investor made monthly contributions equal to 1% of the benchmark portfolio’s value) to 0.72% with no contributions. The alpha fell farther, down to 0.57%, when withdrawing 1% per month.

In other words, when stripping out just the effects of recurring contributions, the annualized alpha from regular tax-loss harvesting was 0.72%. Recurring contributions added an extra 1.08% – 0.72% = 0.36% to this alpha, simply by creating more potential losses to harvest. And conversely, recurring withdrawals reduced the tax-loss harvesting alpha by 0.72% – 0.57% = 0.15%.

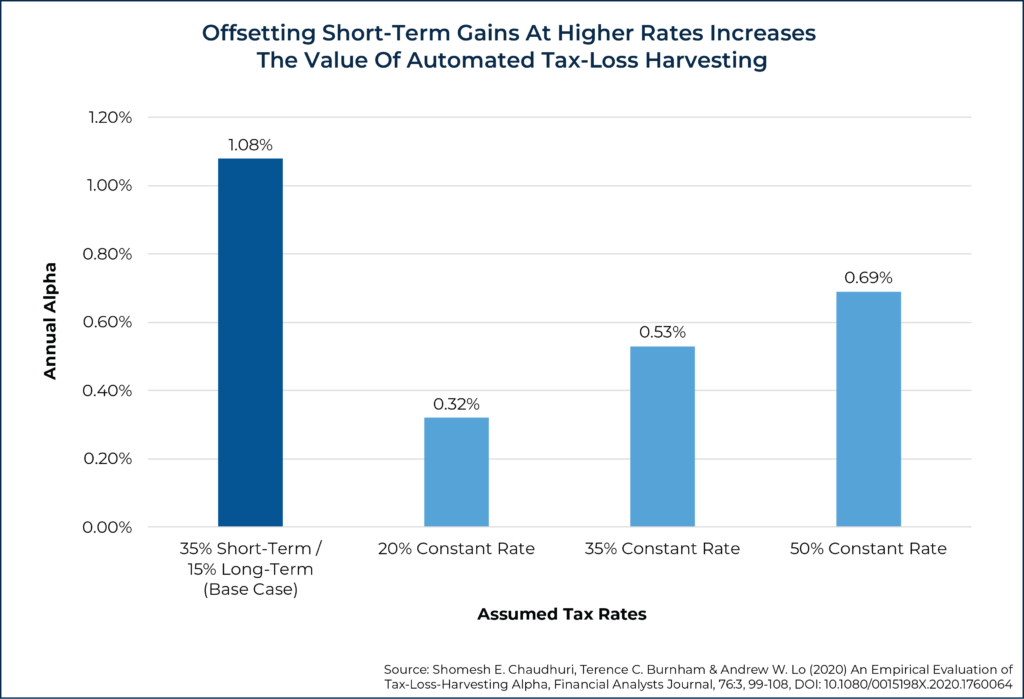

Another area that matters greatly to the real-life value of tax-loss harvesting is the potential for achieving tax-bracket arbitrage by offsetting short-term capital gains (which are taxed at higher ordinary income rates), ultimately creating tax savings if the gain on the recovered investment is taxed at (lower) long-term capital gains rates. Wealthfront’s tax-loss-harvesting white paper itself notes that “Tax-Loss Harvesting is especially valuable for investors who regularly recognize short-term capital gains”. Which may be true, but the average investor – unless they are trading heavily throughout the year – simply doesn’t recognize short-term capital gains all that often. So while an active day trader might see a benefit from tax-loss harvesting that is closer to the 1%+ that platforms like Wealthfront claim, steadier buy-and-hold (or even buy-and-annually-rebalance) investors won’t realize the same benefits.

Subtracting the effects of short-term capital gains (which might not exist, or be very limited, in many investors’ cases) could significantly reduce the advertised value of automated tax-loss harvesting. The FAJ paper examines this possibility by comparing the annual alpha of 4 different tax-loss-harvesting scenarios: the base case scenario, which allows for tax bracket arbitrage by deducting short-term losses at a higher rate (35%) than long-term gains are taxed (15%); and 3 additional scenarios in which all gains and losses, short- and long-term alike, are taxed at the same marginal tax rate (20%, 35%, and 50%, respectively), eliminating the potential for arbitrage.

In the base case scenario with higher short-term rates, the alpha of tax-loss harvesting was 1.08% (as illustrated above, with contributions of 1% per month). In the constant-rate scenarios, the alpha values were considerably lower – only 0.32%, 0.53%, and 0.69% for the 20%, 35%, and 50% tax rates, respectively.

In other words, simply assuming that every short-term loss harvested will be able to offset an equivalent short-term capital gain inflates the estimated alpha of tax-loss harvesting by over 3 times its value, compared to a situation where such tax arbitrage opportunities don’t exist! And in the real world, although everyday investors might occasionally face circumstances where they realize short-term gains (and where harvesting a loss to offset those gains might be exceptionally valuable), those circumstances are often few and far between, since most buy-and-hold investors simply don’t need to trade frequently enough to harvest short-term losses.

So while there may be a certain category of investor who could benefit more from automated tax-loss harvesting – for example, one who makes ongoing contributions to their taxable portfolio (providing a constant source of new opportunities to harvest losses), who is in a high-income tax bracket, and who generates high amounts of short-term gains (thus creating higher tax savings when those gains are offset by harvested losses) – those who don’t match that archetype aren’t likely to see anything near the benefits of automated tax-loss harvesting that are advertised by the providers of those services.

Unfortunately, the FAJ paper didn't estimate the value of tax-loss harvesting assuming neither ongoing contributions nor the ability to offset short-term gains (which is curious, because stripping out those factors would seem to be a more appropriate 'base case' since they have more to do with the investor's actions outside the portfolio rather than the sole effects of tax-loss harvesting). But the alpha would presumably be an amount less than the 0.32% amount illustrated above when assuming a constant tax rate of 20%, since that value also assumes ongoing contributions which themselves add to the value of regularly harvesting losses.

If we roughly assume that, as above, removing the effects of ongoing contributions reduces the tax-loss harvesting alpha by one-third, then the resulting alpha for an investor (who makes no ongoing contributions and realizes no tax-bracket arbitrage) would be 0.32% × 2/3 = 0.213%. And given that the platform fees for robo-advisors and other automated tax-loss harvesting technology start at 0.25% and go up from there, the claim that those fees will be made up for (never mind exceeded) by the added alpha from tax-loss harvesting alone doesn't hold up to the math in the case of many investors whose circumstances aren't already beneficial for harvesting losses.

The Tax Planning Considerations Missed By Automated Tax-Loss Harvesting

One of the main takeaways of the FAJ tax-loss-harvesting paper is that a single automated tax-loss-harvesting strategy can result in a wide range of outcomes depending on the investor’s own financial and tax circumstances. Stated another way, while automated tax-loss harvesting may have its own intrinsic value that comes from more frequent recognition of taxable losses, that value can easily be exceeded by the value of tax-loss harvesting just at certain times, under the right circumstances, where the investor could benefit the most from deferring and/or reducing taxes.

This is because tax-loss harvesting is, at its core, a tax planning strategy, in which the strategy’s value depends highly on the individual investor’s current situation and future plans. In general, the higher the investor’s tax bracket at the time they harvest the losses – and therefore the higher their upfront tax savings from doing so – the more benefit they will get from tax-loss harvesting (though many other factors, like whether the investor plans to ultimately donate the security or hold onto it until death, can also affect the outcome). And as noted above, other factors, such as whether the investor is actively contributing or withdrawing from their portfolio, and whether they have significant amounts of short-term capital gains to offset, can also greatly affect the value of harvesting losses.

Automated tax-loss harvesting providers, however, tend to view tax-loss harvesting as a portfolio management strategy, whose value comes primarily from the type and timing of trades executed by the portfolio manager, with little attention paid to factors outside the investment portfolio. As such, their solutions are not geared toward maximizing the value of tax-loss harvesting by incorporating the investor’s current and future tax circumstances, but instead toward simply capturing taxable losses in the most efficient way. This can be valuable for advisors and their clients when it’s certain that tax-loss harvesting is a good idea – but it doesn’t help with deciding whether or not tax-loss harvesting is even a good idea to begin with.

In essence, the areas in which many providers of tax-loss harvesting software fail to capture all the considerations that make up most of the value of tax-loss harvesting can be summarized as 3 key ‘gaps’:

- The ‘Information Gap’: The facts of investor’s individual tax situation that largely determine how much value they will (or will not) realize from tax-loss harvesting;

- The ‘Review Gap’: The steps needed to properly review client accounts for wash sales to prevent losses from being allowed; and

- The ‘Action Gap’: The additional actions beyond trading that are needed to benefit from the loss.

The Information Gap

The difference between what the client’s own tax circumstances are and what automated tax-loss-harvesting tools are created to do results in an ‘information gap’ between the investor and the software. That is, the software is blind to the investor’s broader tax circumstances, which go a long way toward determining what the investor’s outcome from tax-loss harvesting will be.

By itself, this information gap isn’t necessarily a bad thing; it’s common for many software tools to be valuable only insofar as they can automate low-stakes manual tasks to save time for the human at the helm. However, when tax-loss-harvesting providers (or the advisors who use them) begin to make claims about the value of systematic tax-loss harvesting without any mention of the importance of individual circumstances (or with those caveats buried in fine print, as they often are), it could create a false sense of certainty in the mind of the investor that tax-loss harvesting is a sure bet for them in need of only a system to implement it efficiently – regardless of whether or not their tax circumstances actually make them a good candidate for the strategy.

For example, an investor in the 0% capital gains bracket might be swayed to use a portfolio management tool with an automated tax-loss-harvesting feature based on the service’s claims of added tax alpha. In reality, however, because the investor is in the 0% capital gains bracket, they would realize no tax savings from harvesting losses, and in fact would be more likely to lose value from tax-loss harvesting, since the future capital gains created by the harvested losses could bump them into the 15% tax bracket and result in a higher tax liability than if they hadn’t tax-loss harvested in the first place. Such an investor could be better off harvesting gains instead of losses, in order to raise the tax basis of their portfolio while paying zero tax – but since the software is built only to capture tax losses, it might instead do the opposite, harvesting losses and lowering the basis of the portfolio.

Furthermore, the “automated” part of automated tax-loss harvesting means that not only would the software harvest losses when it makes no sense to do so, but it would keep harvesting losses that would only compound the negative value – a sort of Sorcerer’s Apprentice-like situation, where what seems like a magical tool to add value ends up blindly (and repeatedly) capturing losses that ultimately create zero (or even negative) value for the investor.

The Review Gap

Part of the reason that tax-loss harvesting has traditionally been such a manual process is that there are many steps to navigate to ensure that the loss is properly recognized. The IRS’s Wash Sale Rule disallows any loss when the investor buys a “substantially identical” security within 30 days before or after the date of the sale. The rule applies not just to the account in which the tax-loss harvesting occurred, but to all of the investor’s accounts (including retirement accounts), plus all of their spouse’s accounts as well.

Some of these accounts, like 401(k) plans, for example, might not be directly managed by the advisor. So it is a common practice – even when using a software-supported rebalancing tool like iRebal – to manually review tax-loss harvesting trades to ensure that no potential wash sales slip through the cracks (and just as importantly, to flag any securities that are subject to wash sales to ensure that they aren’t inadvertently purchased during the 61-day wash sale window).

The issue with automated tax-loss-harvesting solutions is that there is no such manual review process; the trades are automatically placed according to the software’s algorithms. And while many providers tout the ability of their platforms to spot and avoid potential wash sales, that doesn’t make it a certainty that wash sales won’t happen. The software might not ‘see’ all of the investor’s accounts, meaning that if the investor holds a security subject to the wash sale rules in an outside account (such as in a 401[k] plan or in a spouse’s account), a wash sale could inadvertently occur even if the rebalancing software works the way it is supposed to.

For investors who use automated tax-loss harvesting software, then, there’s the risk that the ‘review gap’ between the securities the software can ‘see’ and the rest of the securities owned by the client can lead to inadvertent wash sales that cause losses to be disallowed, which can have a significant effect on the investor’s tax bill (along with any applicable penalties and interest) – especially when those disallowed losses are substantial.

Importantly, an advisor who recommends automated tax-loss harvesting or employs it in their clients’ accounts could be liable for any harm done to the client as the result of an error or oversight (as well as subject to other disciplinary action: In one notable example, the robo-advisor Wealthfront was fined $250,000 by the SEC in 2018 for advertising that its tax-loss harvesting program would monitor clients’ accounts to avoid wash sales, when in fact the SEC found that wash sales occurred in at least 31% of client accounts over a three-year period).

The Action Gap

An important but frequently forgotten consideration with tax-loss harvesting is that attaining the long-term benefits of harvesting losses requires additional actions beyond just harvesting the loss.

First, the investor must have some capital gains for the loss to offset. Although capital losses can be used to offset up to $3,000 of ordinary income per year, any losses beyond that are carried over into future years when there are gains to offset – but until that happens, there is zero tax benefit from harvesting losses.

Second, in order to benefit from the tax deferral aspect of tax-loss harvesting, the investor needs to reinvest the upfront tax savings created by the loss (either by contributing more funds to the portfolio, or by reducing withdrawals by the amount of the tax savings). Much of the tax-deferral value of tax-loss harvesting is built around the time value of money, and so that value is lost if the upfront tax savings is spent (or simply sits idly as cash in the investor’s bank account) rather than being reinvested.

Automated tax-loss harvesting software tends to focus solely on realizing losses and leaves the other actions for the investor to perform themselves. The ‘action gap’, then, is the difference between the actions the software performs, and all of the actions that need to be done to fully realize the value of tax-loss harvesting.

Even though robo-advisors like Wealthfront assume that there are gains to offset and that the upfront tax savings are reinvested when calculating the benefits of tax-loss harvesting provided by their service, they elide over the fact that these things don’t happen automatically – instead, they frame it as a ‘set-it-and-forget-it’ process running in the background and requiring no action from the investor. So even when investors could see a benefit from automatic tax-loss harvesting, there’s no guarantee that they’ll ultimately receive that benefit unless they can actually realize the tax savings of the loss and reinvest those savings for future growth.

Why Opportunistic Tax-Loss Harvesting Is (Usually) Better

The presupposition of automating tax-loss harvesting is that there is never any real downside to harvesting losses, and that even though the potential value might not be quite as high as advertised, it at least provides some benefit. And since software can automatically check for and capture losses, there is no time cost in implementing automated tax-loss harvesting, at least in theory.

But in reality, harvesting losses can destroy value – if the client’s overall tax situation means the future tax liability will exceed the upfront savings, if the loss is disallowed by a wash sale and results in tax penalties or interest, or if a failure to realize offsetting capital gains or to reinvest the upfront tax savings forgoes the opportunity to benefit from the tax deferral of harvesting losses. All of these issues can fall through the cracks of tax-loss-harvesting software, so there is a real potential downside for automating tax-loss harvesting if the investor doesn’t benefit from harvesting losses to begin with.

Unless it always makes sense for an investor to harvest losses whenever they are available – and it’s questionable as to whether that would ever be the case for any investor – automatic tax-loss harvesting could backfire any time it doesn’t get the trade ‘right’ based on the client’s broader tax picture (which the tax-loss-harvesting software has no knowledge of).

And while an advisor can combine automated tax-loss harvesting with a process of regularly checking in on those areas of the client’s tax situation to ensure it’s still appropriate to harvest losses, doing so seriously undermines the ‘automated’ part of automated tax-loss harvesting – making it questionable as to whether the software is creating any value at all in terms of either dollar or time savings.

An alternative approach would be to focus on harvesting losses only when it makes sense within the context of the client’s tax situation. Though this approach might not maximize the total amount of losses realized for tax purposes (as automated tax-loss harvesting is often designed to do), it can help to ensure that the impact of those losses is as positive for the investor as possible.

As the FAJ research highlighted above showed, the value of automatic monthly tax-loss harvesting was greatly reduced when removing the effects of certain client circumstances, such as making recurring portfolio contributions or having the ability to offset short-term capital gains. It follows, then, that much of the value from automated tax-loss harvesting comes not from maximizing the losses harvested, but from the timing of those losses: Losses harvested when the circumstances are ideal will be much more valuable than those in less-ideal circumstances, regardless of whether they are generated by an automated or a manual process.

Which means that it isn’t really necessary to automate tax-loss harvesting to achieve most of the benefits (and, given the risks to automation outlined above, many advisors might not wish to hand over the responsibility of doing so to automated software) – what’s necessary is to recognize the circumstances in a client’s tax situation that would make tax-loss harvesting valuable to them.

In essence, this represents a more tactical approach to tax-loss harvesting rather than an automated one. Instead of maximizing the number of losses realized by identifying and capturing losses every time they are available (which could result in a large number of harvested losses that ultimately have very little, or even a negative, real value to the investor), the tactical approach focuses on capturing losses only when the investor’s tax circumstances make it likely that they will realize significant value from doing so – while the losses that don’t matter are left alone.

How To Implement A System Of Tactical Tax-Loss Harvesting

For advisors who serve dozens or even hundreds of clients, it’s easy to talk about maximizing the value of tax-loss harvesting but more difficult to implement at scale. Given the limits of each advisor’s time and resources, there will be necessary trade-offs between how often tax-loss-harvesting opportunities can be reviewed, how thoroughly each client’s tax situation can be analyzed each time, and how many clients can be served effectively. Creating a system that strikes a balance between these three factors requires an efficient way to identify good candidates for tax-loss harvesting, review all of the necessary considerations before making a trade, and then execute the trades themselves.

To identify clients who are potential candidates for tax-loss harvesting, advisors could implement a ‘scoring’ system composed of factors used to rate the potential value of tax-loss harvesting.

For example, the advisor could add together the number of the following factors that a client matches:

- The client is expected to have realized capital gains this year

- The client is expected to have short-term capital gains this year

- The client is in a higher income tax bracket today than they expect to be when they liquidate their portfolio

- The client has a long time horizon before they expect to liquidate their portfolio

- The client expects to die with and/or donate the securities being harvested

- The client has no unused carryover losses from previous years

The higher the number of factors that apply to a client, the more benefit they are likely to realize from tax-loss harvesting.

Conversely, advisors could also use factors to flag clients who would not be good candidates for tax-loss harvesting, such as:

- The client is in the 0% capital gains tax bracket

- The client expects to be in a higher tax bracket when they liquidate their portfolio than they are in today

- The client plans to liquidate their portfolio in the next year

Though it may be imprecise in terms of quantifying the exact value of each loss, such a system can help advisors quickly identify and prioritize clients who are likely to benefit the most from harvesting losses. While client situations do change over time, this type of review may only need to be done once per year for many clients, making it possible for advisors to easily refer back to a client’s ‘score’ if and when tax-loss harvesting opportunities arise during the year.

After the advisor has identified those clients who stand to benefit the most from harvesting losses, they can then incorporate the tax planning elements of tax-loss harvesting with the portfolio management side. For example, if the advisor rebalances client accounts on a quarterly schedule, then that quarterly rebalancing process can be used to identify tax-loss harvesting opportunities – but only for those clients for whom it makes sense to harvest losses.

Even if rebalancing is done more frequently, such as on a monthly schedule, having each client’s tax-loss-harvesting score on hand makes it simple to decide which clients are good candidates for tax-loss harvesting (or who might warrant further review before going ahead with harvesting losses).

Once the candidates for tax-loss harvesting are identified, using a checklist can be a best practice to ensure that other considerations that might slip past automated software (like checking the client’s held-away accounts for potential wash sales) are accounted for, and to ensure that the appropriate follow-up actions after the loss is harvested – such as switching back from the ‘secondary’ to the original security after the 30-day wash sale period, and reminding the client to reinvest their upfront tax savings – are taken care of.

Technology can often be a valuable solution for automating time-consuming manual tasks. But although the process of tax-loss harvesting does contain a fair amount of manual work, using automated tax-loss-harvesting software does not replace all of the actions needed to ensure that clients fully realize the potential benefits of tax-loss harvesting. Because these automated programs tend to view the process of harvesting losses solely from a portfolio management standpoint, they often miss the broader tax planning circumstances that can be the difference between a positive, neutral, or negative result. Which suggests that for fiduciary advisors who are obligated to act in our clients’ best interests, using automated software to harvest tax losses – especially when the program doesn’t account for a client’s individual circumstances that dictate the ultimate outcome – is a risky proposition.

Harvesting losses in a more tactical way – led by tax planning, and at best only supplemented by automated software – might not maximize the number of possible losses realized for every investor; however, that isn’t the point. What ultimately matters is that the system ensures that the losses that are realized are those that will benefit the client most in the long run!

There is some great content in this article. Would have been good to mention Morningstar’s Total Rebalance Expert – that has all of the tax savings strategies built-in. This includes TLH (with minimum settings & automatic wash sale avoidance), short-term gain avoidance, and capital distribution avoidance.