Executive Summary

Even in a low interest rate environment, the reality is that prepaying a mortgage is the equivalent of a ‘guaranteed’ bond return, at a yield that is better than cash and arguably even appealing on a risk-adjusted basis in a world of potentially low equity returns. However, the caveat is that while making mortgage prepayments can have long-term benefits, they’re only very long term benefits – as prepaying a mortgage to reduce the cumulative loan interest and term of the loan may not be felt for a decade or two thereafter.

One alternative to more immediately enjoy the “benefits” of prepaying a mortgage, though, is to request a mortgage recast. By recasting the mortgage – re-amortizing the loan balance over the original term – the borrower enjoys immediate relief in the form of lower future mortgage obligations. Of course, the original mortgage payment can still be made. But at least the borrower has the option to pay less if desired… which can be especially helpful if the household has a financial shock, from unemployment to a medical event or short-term disability.

Unfortunately, though, in today’s mortgage environment, recasting is not easy. Most lenders assess a small but not trivial processing fee every time a recast is requested. And it must actually be manually requested, and then manually approved by the loan servicer, and by the investor if the mortgage has been resold since its origination. In addition, not all types of mortgage loans are even eligible in the first place.

Yet the question arises: what if mortgage recasting were not only easier, but automatic, such that a borrower who makes a prepayment automatically and immediately receives the benefit of a reduced future mortgage obligation? With automatic recasting, mortgage prepayments no longer just produce a long-term (but highly intangible) benefit; it also produces immediately tangible relief, in the form of a reduced mortgage obligation. Which in turn improves the household’s financial flexibility, and can even improve the stability of the overall mortgage market by both reducing default risk (since the mortgage payment obligation is smaller and easier to maintain) and also reducing loss exposure for lenders (as ongoing prepayments build more equity for the borrower, reducing the risk of a lender that is compelled to foreclose on a default).

In fact, ironically the potential positive incentives for automatic recasting may be so significant, that the biggest problem could become the tendency for households to become “house rich and cash poor” by systematically paying off their mortgages in advance. Still, given the difficulty that many consumers have in saving by any means except home equity, and the availability of reverse mortgages, perhaps this would not be such a bad outcome after all?

The Bad Psychology Of Mortgage Prepayments

Most mortgages today allow borrowers to make principal prepayments without any penalty. In many cases, this is valuable simply because it leaves the borrower with the flexibility to refinance the mortgage – which is technically taking out a new mortgage against the house, and using the proceeds to fully prepay the “old” mortgage. In other cases, though, the goal is simply to take some available extra cash – whether from a bonus at work, a lump sum inheritance, or simply by making an extra “13th mortgage payment” each year – and prepay a portion of the loan balance in order to reduce the amount of future loan interest.

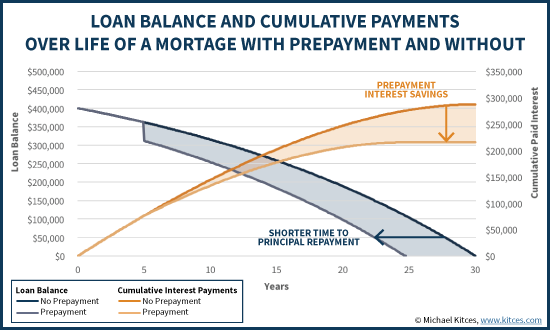

Notably, though, virtually all mortgages still have fixed payment obligations. Which means that even if you prepay to reduce your account balance, your mortgage payment doesn’t change. Instead, by making the additional principal payment, the remaining balance is simply paid off faster… in part because the borrower whittled down the principal itself with the prepayment, and also because the borrower won’t incur as much in cumulative interest payments given the reduction in loan principal.

Example 1. Jeremy is 5 years into a 30-year mortgage taken out for $400,000 at 4%, the (original and ongoing) monthly mortgage payment is $1,910 (principal and interest), and by the end of year 5 the loan balance is down to $361,790.

If at this point Jeremy receives a big $50,000 bonus, and wants to prepay the mortgage, the payment will remain at $1,910. However, making the prepayment means that instead of taking another 25 years to repay the mortgage, it will be paid off in just 20 years (year 25) instead. And by doing so, the cumulative amount of loan interest that Jeremy will pay is reduced by $71,980 as well.

A significant challenge of this scenario is that while there is a substantial reduction in cumulative loan interest paid, and the borrower does ultimately avoid 5 years of mortgage payments… none of those benefits are experienced until nearly two decades later. Yet the loss of liquidity – the cash that is taken to prepay the mortgage – is tangible and felt immediately!

This is especially concerning, given that research in behavioral finance has shown that people disproportionately discount the value of dollars (including savings) that only occur in the distant future. Dubbed “hyperbolic discounting”, the recognition that we prefer near-term liquidity and immediate cash over alternatives that would have a longer-term benefit means we can make very “irrational” decisions sometimes. Especially if the only benefits occur in the distant future, when we’re most likely to underweight them.

Accordingly, it is perhaps not surprising that few consumers ever choose to prepay a mortgage. Since the benefits are only ever felt a decade or two later, it’s hard to get very excited about the strategy, even if it can have a very favorable long-term financial impact!

Recasting A Mortgage After Principal Prepayment

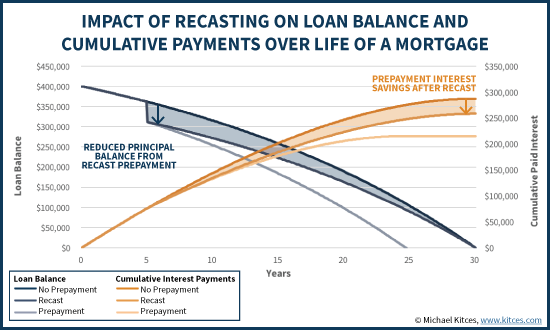

Fortunately, there actually is an alternative treatment for mortgage prepayments, besides “just” shortening the remaining term of the mortgage and saving on the interest. Instead, the lender can also “re-amortize” the new mortgage balance over the remaining time period.

Also known as “recasting” a mortgage, the benefit of the strategy is that by stretching the new account balance out over the original time period, the monthly mortgage payment obligation is decreased.

Example 2. Continuing the prior example, if Jeremy chose to recast the mortgage after his $50,000 prepayment, the remaining loan balance of $361,790 over the remaining 25-year term at the original 4% interest rate would result in a monthly principal and interest payment of $1,646, instead of the original $1,910.

Notably, Jeremy’s decision to recast the mortgage to be permitted to make the lower monthly payment of $1,646 means the loan will still extend for the original 30-year time period. In the end, Jeremy will still benefit from some savings on loan interest – thanks to the $50,000 prepayment itself, and the loan interest it won’t incur – but not as much interest savings as he would have had by continuing the original mortgage payment, since the lower mortgage payments do allow the remaining principainsteadl to incur loan interest for a longer period of time.

Of course, the reality is that even after recasting the mortgage, the original borrower could still keep making the original mortgage payments. Reamortizing only reduces the mortgage payment obligation (in the example above, by $264/month); choosing to make a higher payment, which at that point would simply be additional prepayments, is still permitted. And given that the loan still has the same principal balance (after the lump sum prepayment) and the original interest rate, if the borrowers continues the original payments, the loan will still be repaid just as early as if the recasting never occurred, with the associated full savings on loan interest.

Nonetheless, the virtue of the mortgage recast if that if life or financial circumstances change, and the borrower needs to make lower loan payments for a period of time, he/she has the option of doing so! In other words, recasting a loan after making a prepayment towards it allows the borrower to enjoy all the interest savings of prepayment, and provides greater household cash flow flexibility if it’s needed (as the required mortgage payment is lower).

The Cost And Hassles Of A Manual Mortgage Recast

Unfortunately, one of the biggest caveats of recasting a mortgage is that it’s a manual process. In other words, it doesn’t happen automatically when a prepayment occurs; instead, a specific request must be made for it to happen.

In addition, once a request to reamortize the mortgage is made, there is a hard dollar cost, with banks often charging fees of $150 - $250, or more, just to process the recast.

Furthermore, there are many practical limitations in today’s marketplace. For instance, not all mortgage loan types are even eligible for a recast; conforming Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae loans are generally able to be recast, but FHA or VA loans are not, and whether a jumbo loan can be recast is up to the lender. And even where permitted, the recasting process itself requires that the loan servicer must sign off to allow the recast. If the mortgage has been re-sold to investors, the loan servicer also must obtain the investor’s approval as well.

Given these administrative hassles, many lenders require a certain minimum amount of prepayment in order to request a recast; for instance, a lender might stipulate that no recasting is permitted unless the prepayment is at least 10% of the outstanding loan balance.

In light of these constraints, it is perhaps not surprising that in practice, requests to recast a mortgage are very rare. The WSJ reports that between the nearly 25 million mortgages held at Chase and Bank of America, barely 0.02% of them are recast each year. Though again, that’s not entirely surprising in the current marketplace, given that there’s a hard dollar cost for additional flexibility that may or may not be needed, not all loans are even eligible, and the mere fact that it’s a manual process with additional paperwork to sign is enough to slow many borrowers down.

Automatic Loan Recasting To Incentivize Savings Behavior?

Notwithstanding these practical challenges and costs to recasting in today’s environment, though, the question arises: could consumer behavior be changed for the better if it were easier to reamortize a mortgage? For instance, if recasting was automatic instead, every time a prepayment occurs?

Of course, as noted earlier, making recasting automatic is a moot point financially for any borrower who is able to and chooses to simply continue the original mortgage payment, as the total cost is the same (because the loan is still repaid early). And ostensibly, continuing to make the original mortgage payment will be manageable for most, since the borrower was already paying on the mortgage and had enough extra money to make a prepayment!

However, from the perspective of financial planning flexibility, and behavioral incentives, automatic recasting could be very powerful. After all, with automatic recasting, there’s now an immediate household benefit in making a prepayment: your monthly mortgage obligation gets smaller for every month thereafter. For instance, with the earlier example of the mortgage at 4% with a remaining account balance of $311,790 over 25 years, every $1,000 prepayment results in a reduced monthly mortgage obligation of $5.28. (Notably, the payment-savings-per-$1,000-prepayment will vary by mortgage scenario, depending on the interest rate and remaining term of the loan.)

In other words, even though you still can make the original mortgage payment, automatic recasting gives households an instant improvement in financial flexibility by reducing the required payment. Of course, the caveat is that freeing up a household’s cash flow makes it easier for them to slow their mortgage payments in the future (since by definition recasting reduces the mortgage obligation). Yet on the other hand, recasting only occurs when the borrowers are making their current loan payments and additional prepayments in the first place, so by definition the household is already spending even less, just to have the prepayment and recasting available. In fact, that’s the whole point – households that can further reduce their consumption, over and above their existing mortgage obligation, are rewarded with greater mortgage flexibility going forward (which is nice to have, even if they don’t need it).

In addition, for households that value liquidity – which seems to be most of them, given the research on hyperbolic discounting – reducing the monthly mortgage obligation reduces the need for cash reserves and the required size of emergency savings as well. Which provides yet another indirect financial benefit – because keeping emergency reserves cash earning 0%, while you have a mortgage at 4%, is technically a form if negative arbitrage that has a double cost (paying the 4% on the mortgage, and the foregone opportunity cost of the emergency reserves in cash).

Furthermore, the greater cash flow flexibility after a recast mortgage payment can potentially improve future job mobility and improve the household’s overall financial stability. For instance, lower future mortgage payments give the borrower more flexibility to change jobs or careers (which may require one income step back to take two steps forward), and in a world where medical events that cause short-term (or long-term) disability are a leading cause of bankruptcy, making it easier to reduce monthly mortgage obligations has the potential to reduce mortgage default risk in the first place.

From the lender’s perspective, allowing automatic recasting is also appealing, because the recasting incentive for mortgage prepayments (to reduce future mortgage payment obligations) would result in lower loan balances, and greater home equity for the borrower, which reduces the exposure of the lender to a financial loss in the event of a default.

Of course, the one clear caveat from the financial planning perspective is that consumers who put “too much” into their home can become house-rich and cash-poor. Nonetheless, prepaying a mortgage is still the equivalent of a “guaranteed” bond return at a relatively appealing yield (compared to other bonds), and is even appealing relative to equities in a potentially low return (high valuation) environment for stocks. In addition, the reality is that having a concentration of wealth in home equity is ultimately not really a problem of prepaying the mortgage (and recasting it), per se, but of buying too much house relative to the individual’s net worth in the first place. In other words, if you don’t want “too much equity” tied up in the home, the solution isn’t to avoid prepaying the mortgage, it’s to not buy as much home to begin with! And fortunately, reverse mortgages are at least a potential contingency vehicle to extract the equity back out in the later years, if it’s needed.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that the current structure of mortgage prepayments is a terrible incentive for people to actually build equity above and beyond their minimum mortgage obligation, because the only ‘benefit’ is in the very distant future. Making it easier to recast – or making the mortgage recasting process automatic – is a far better incentive, because it provides an immediate reward in the form of immediately reduced mortgage payment obligations, which is a powerful feedback mechanism to encourage prudent saving behavior. And automatic recasting has the added benefit of reducing loss exposure for mortgage lenders, reducing household cash flow obligations, reducing the need for idle emergency savings, and giving consumers more flexibility to make human capital changes (i.e., job or career changes that necessitate a temporary income setback), while also making households more robust against unexpected disasters (e.g., medical events or unemployment or disability).

So what do you think? Have you ever counseled a client to recast a mortgage? Do you think automatic recasting would be a valuable incentive for consumers to spend less and save more? Or are you concerned it might work “too well”, leading people to save effectively, but become too “house rich and cash poor” in the process? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!