Executive Summary

One of the virtues of cash value life insurance is that insurance companies are willing to make loans against the policy at relatively favorable interest rates, because the insurance company knows that it can always foreclose on the policy (i.e., force its surrender) as collateral to repay the loan.

Unfortunately, though, while the availability of a life insurance policy’s cash value ensures that the loan will never be “underwater” with recourse to the borrower, the bad news is that the surrender of the life insurance policy itself can still be fully taxable for a substantial gain. Even if the policyowner doesn’t get any of the proceeds, because they’re used to repay the loan. Ultimately, the only way the upside of a life insurance policy becomes fully tax-free is if it matures as a death benefit.

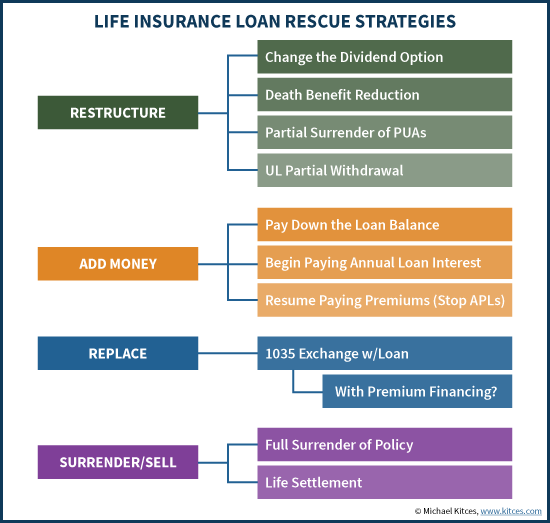

In fact, the reality that the only way to use a life insurance policy’s cash value to repay a loan tax-free is via the death benefit leads to a number of “rescue” strategies for life insurance policies with substantial loans, specifically to help ensure that the policy remains in place until the death of the insured.

In some cases, the accrued loan interest on a life insurance policy is so severe that there’s no way to save the situation – necessitating either a surrender of the policy, or perhaps a life settlement sale transaction for an older insured.

But fortunately, it’s often feasible to sustain the policy with some combination of restructuring the policy’s dividends and death benefit, engaging in partial surrenders or withdrawals, contributing some additional dollars into the policy (either as premiums, or to pay loan interest or repay principal), or even exchanging to a new “life insurance rescue policy” that transfers the policy’s cash value – along with the loan itself – in a tax-free 1035 exchange.

Of course, ideally the insurance policy will be monitored all along, to avoid ever reaching a “surprise” situation where a life insurance policy loan has compounded to the point that it needs to be rescued. But whether it’s a proactive “Bank on Yourself” borrowing strategy, or just accidentally accruing a loan through the Automatic Premium Loan provision on a whole life policy, sometimes a substantial loan does accrue, and it’s necessary to take steps to rescue the policy before an adverse tax consequence results!

The Problem With Life Insurance Loan Strategies

Life insurance strategies that rely on loans are often characterized as a technique to “borrow money from yourself” or “Bank On Yourself”. Yet the reality is that in truth, a “life insurance loan” is really just a personal loan made to an individual from a life insurance company, which uses the cash value of the life insurance as collateral for the loan.

Fortunately, life insurance companies will make personal loans at rather favorable interest rates, primarily because the insurance company directly controls the life insurance cash value serving as collateral for the loan. As a result, the insurance-company-as-lender can be confident that the collateral is there, available, unencumbered, and able to be easily foreclosed upon and liquidated if necessary.

Accordingly, this is also why insurance companies won’t allow life insurance “policy loans” to ever exceed the cash value of the life insurance policy – because the insurer doesn’t want to be on the hook for an unsecured loan. Instead, if/when the outstanding loan balance reaches (or gets “too close”) to the remaining cash value, the insurance company forces a liquidation of the insurance policy, and uses the cash value proceeds to repay the loan.

Unfortunately, though, while life insurance companies structure policy loans in a manner that protects their exposure as a lender, it doesn’t always turn out favorably for the borrower. The good news is that by virtue of the structure, the policyowner can never be on the hook for a loan that’s greater than the available cash value. The bad news, however, is that if the policy has to be liquidated to repay the loan, the policyowner may still receive a Form 1099-R for the underlying gains in the policy. This can be especially problematic, since there won’t actually be any remaining cash value to pay the tax bill that comes from this “phantom income”.

Example. Charlie has a universal life policy into which he’s paid $125,000 of premiums, and the policy has a current cash value of $200,000. Many years ago, Charlie borrowed $100,000 against the policy, and after more than a decade of compounding loan interest, the policy loan balance has now reached the $200,000 cash value. As a result, the insurance policy lapses, and the insurance company keeps the $200,000 cash value proceeds to pay off the $200,000 loan. However, since the policy was worth $200,000 at liquidation, and the cost basis was only $125,000, then Charlie will receive a Form 1099-R for $75,000, and have to pay taxes on the gain, even though he doesn’t receive any cash upon liquidation.

From the tax code’s perspective, this result occurs because Charlie still had a $200,000 cash value and $125,000 of cost basis, which meant there was a $75,000 gain. The fact that Charlie had to use the $200,000 of proceeds to repay the loan doesn’t change the fact that he got $200,000 out of the policy, even if it didn’t come to him personally. The tax bill is still due.

In addition, there’s the secondary challenge that once a life insurance loan causes the policy to lapse, the death benefit vanishes as well, as the policyowner has lost the insurance coverage itself!

As a result of these dynamics, in some cases it makes sense to try to “rescue” a life insurance policy that is in distress due to a substantial loan, either to avoid the adverse tax consequences (which vanish if the policy can remain in force until the insured passes away), or simply to retain the value of the death benefit itself (which is otherwise lost when the policy lapses).

What Is A Life Insurance Loan Rescue?

A life insurance loan rescue plan (or “life insurance rescue” for short) is a way to describe various strategies that aim to avoid the tax consequences of lapsing life insurance due to a policy loan, ideally while maintaining at least some of the life insurance death benefit as well.

The starting point in trying to avoid a loan-driven policy lapse and rescue the policy, is to do a thorough evaluation of the current policy as it stands today.

Key information that must be gathered when reviewing a life insurance policy includes:

- In-Force Ledger (IFL). An in-force ledger is a projection from the life insurance company of how the policy is expected to perform from here, based on current crediting rates, current loan rates, current premium payments, etc. The IFL will help to clarify just how serious the loan situation really is, which in turn will guide the cost and consequences of the various rescue alternatives.

- Type of Policy. Be certain to figure out what kind of policy you’re actually dealing with in the first place. Is it a whole life policy that has ongoing premium requirements, or a universal life policy that is flexible with respect to its premium payments?

- Premium Commitments. Are premiums currently being paid into the policy? Do they have to be paid (whole life policy) or are they flexible (universal life policy)? Is the policy already paid up?

- Ownership. How is the policy owned? Is it in the name of the insured? Or is there a third-party involved, where making premium payments (or loan repayments) could have gift tax implications? Or is the policy owned inside of a trust, where the trustee must be involved?

- Underwriting Classification and Health of the Insured. What was the original underwriting classification on the policy? Preferred? Standard? Table-rated? What is the current health of the insured? Is he/she in worse health than when the policy was originally issued? Or is he/she actually in better health now (e.g., lost weight, got healthier, further recovered from prior health event, etc.)?

- Who are the Beneficiaries. In considering the ramifications of whether to rescue the life insurance policy and which approach is best, be cognizant of who the beneficiaries are. Some may benefit more from certain rescue strategies than others.

- Purpose of the Loan. What was the context of the life insurance loan in the first place? Was it for a temporary purpose that has ended, and the loan could simply be repaid? Was the loan even intentional in the first place, or was it triggered accidentally (e.g., as an Automatic Premium Loan [APL] from a whole life policy)?

- Purpose of the Policy. What was the original purpose of the life insurance policy? Is that need still relevant? What is the need/value to keep the policy going forward – either for its cash value, its death benefit, or both?

Once this key background information about the policy has been gathered, it’s feasible to start evaluating potential life insurance loan rescue strategies – with an eye towards the ultimate purpose of the policy itself, which will help to guide whether it’s most important to delay or permanently avoid a potentially large tax liability by keeping the policy going until the death of the insured, to actually maximize or at least maintain the remaining death benefit because it’s still more appealing to hold the policy until death (for its implied rate of return) rather than surrendering it to eliminate the loan, or simply to try to get as much of the remaining value as possible out of the policy before it lapses.

Restructure The Life Insurance Policy With A Loan

The first approach for a life insurance policy loan rescue is to restructure the policy and its key components, in an effort to help the policy survive longer (i.e., until the insured dies and the policy loan can be repaid tax-free from the death benefit).

Changing The Dividend Option On A Participating Life Insurance Policy

The first structuring option is to change the dividend option. For any permanent policies that are “participating” policies (i.e., paying a dividend), there are several options available for how dividends will be used. The most common (and often default) option is to purchase “Paid-Up Additions” (PUAs), which as the name implies are small amounts of additional coverage that are fully paid up when purchased. The good news about PUAs is that they’re typically quite favorable priced for additional insurance (in part because they include no acquisition costs in the pricing); the bad news is that if there’s a loan that is compounding, buying more insurance while the main policy flounders is not a good strategy!

Fortunately, the dividend option can be changed at will. It simply requires a request to the insurance company to make the change. For a policy with a problematic loan, the best option will typically be to redirect the dividend to pay the loan interest, and if the dividend is larger than the required loan interest, the remainder can be used to pay down loan principal as well. If the dividends are large enough, they may eventually fully extinguish the loan, allowing the policy to sustain! (And after that point, the dividends can be directed back to purchase PUAs again, or simply be used to pay the premium on the policy itself, if applicable.)

Death Benefit Reduction Or Partial Surrender

The next option to improve the sustainability of a life insurance policy with a hefty loan is to restructure the cash value or death benefit to reduce the ongoing cost to sustain the policy.

If it’s a universal life policy, the most straightforward path is to reduce the death benefit. Unlike changing the dividend option, this will require completing paperwork to substantiate the request – since reducing a death benefit is no small change, as once done it is typically permanent (or at least, increasing the coverage again would likely require additional underwriting). The obvious downside to reducing the death benefit is that it literally reduces the death benefit – which means if the goal was to maximize the death benefit in the long run, this isn’t appealing. However, for those who are just trying to ensure the policy remains in force without lapsing and causing a tax bill, a death benefit reduction is an appealing option, as it reduces the ongoing Cost Of Insurance (COI) charges in the policy, which allows the cash value to grow faster (or at least decline more slowly), extending the crossover point where the policy loan potentially exceeds the available cash value (which would otherwise cause a lapse).

Another option for a universal life policy is to take a withdrawal from the cash value itself, and use the funds to pay down the loan balance. As long as the policy is not a Modified Endowment Contract (MEC), or subject to a “force-out” for overfunding under IRC Section 7702B – which can be confirmed with the insurance company – withdrawals from a universal life policy are treated as a basis-first return of principal and are not taxable (until all basis has been recovered). This provides a means to take a tax-free withdrawal from the policy (up to basis), and use it to immediately repay a portion of the loan. Notably, depleting the cash value with a withdrawal may mean the policy will still ultimately need another contribution (i.e., more premiums) to sustain in the long run; nonetheless, if the cash value is in a downward spiral towards lapse anyway, a withdrawal to repay the loan will help extend the life of the policy, given that the crediting rate of the cash value is always lower than the interest rate of the loan compounding against it (which for newer policies might be a 0.5% to 1% spread, but on older policies can be a 2% spread or more).

In the case of whole life policies, where the death benefit and cash value structure is less flexible, there’s no way to take a non-taxable withdrawal from the policy, nor to just reduce the death benefit; however, it is possible to engage in a “partial surrender” of the policy, which liquidates a portion of the policy, returns a portion of the cash value, and reduces the death benefit accordingly. A partial surrender is a taxable event, but a partially taxable event that frees up cash to repay a life insurance loan may still be better than allowing the loan to outcompound the cash value, leading to a total surrender and a fully taxable event for the whole policy!

In addition to the potential of a partial surrender, it’s notable that a participating life insurance policy that has previously been purchasing PUAs can do a partial surrender of just the PUAs to free up cash to repay the loan. The “good” news of surrendering PUAs is that because that portion of the coverage is already paid up, its cash value tends to be high relative to the death benefit, which means the policyowner can give up less death benefit to get much more cash value out (at least compared to a partial surrender of the underlying policy itself). The “bad” news, though, is that a partial surrender of PUAs is still a taxable event; nonetheless, if the PUAs are available to liquidate, it’s a far more tax-efficient and cash-value-efficient path. For a policyowner who probably “should” have been using dividends to pay down the loan already, and was buying PUAs instead, this also provides a relatively efficient means to unwind the PUAs and redirect them back towards reducing or eliminating the policy loan.

Put More Cash Into The Life Insurance Policy

Beyond restructuring the policy to improve its longevity, the second option is simply to outright put more money into the policy.

The first approach is simply to use outside dollars to pay down the loan on the policy, either in part or in full. To the extent the loan balance is reduced, it will slow the rate of compounding and increase the likelihood that the policy will last until it “matures” as a death benefit (i.e., the insured passes away and the loan balance is repaid from the death benefit proceeds). If the loan can simply be repaid altogether, then the entire issue is absolved. This strategy is especially appealing if the policyowner carries a substantial amount of money in a bank or savings account, or even has a large bond allocation – as it makes little sense to have dollars in a money market or bond paying 1% to 3% while simultaneously accruing a life insurance policy loan at 4% to 6% or more (depending on the policy loan terms).

If there isn’t enough money available to fully (or materially) repay the loan, the next way to ‘rescue’ the policy is to at least begin paying the annual loan interest, to prevent the loan from compounding further. To the extent that the policy cash value continues to grow, but the loan interest is paid annually, the policy is either assured of lasting with ongoing premium payments (if it’s a whole life policy), or at least is much more likely to be able to sustain (if it’s a universal life policy, depending on subsequent performance). For someone who’s already paying ongoing premiums into the policy, consider the loan interest a form of higher premiums to ensure that the policy lasts (preserving the death benefit, and avoiding the adverse tax consequences of lapsing).

Of course, this presumes that the policyowner is otherwise making the necessary premium payments in the first place. Which isn’t always the case. In point of fact, a common reason to have a sizable and problematic life insurance loan in the first place is when a policyowner stops making premium payments on a whole life policy – because a whole life policy must receive annual premium payments (unless it is fully paid up), and failing to pay premiums will usually trigger an Automatic Premium Loan (APL) provision where the insurance company provides a loan to the policyowner and immediately uses it to pay the premium. The end result is that the policyowner has no cash out of pocket for the premium, but a loan starts to compound! Beginning to pay premiums again will stop the APLs from continuing to add to the loan balance… though it still doesn’t resolve the existing policy loan at that point, which still must be contended with.

In the case of a universal life policy, there is no direct requirement for ongoing premiums to be made. The whole point of a universal life policy is that premiums are flexible. However, if insufficient dollars go into the policy to sustain the cash value, the policy can lapse… and if there’s an outstanding loan on the policy, it will just lapse even faster (when the cash value dips down to the loan balance, as opposed to needing to go all the way to $0 to lapse). Thus, putting additional premiums into a universal life policy can help shore up its sustainability – though notably, given that the crediting rate on universal life policies will still be lower than the interest rate on policy loans, extra dollars going into a UL policy should generally be used to pay down the loan first, and only then to add additional premiums to the cash value (if necessary).

Life Insurance Loan Rescue With A 1035 Exchange (If You Can)

If just restructuring the life insurance policy with a loan isn’t enough, and the policyowner is unwilling or unable to put additional cash into the policy to support it, the next alternative is to explore a policy replacement – exchanging the original life insurance policy with a loan to a new policy that may be more sustainable.

Notably, amongst life insurance agents, the strategy of replacing a life insurance policy with a loan for another one is the primary approach to execute a life insurance loan rescue… in part because the life insurance agent often has an opportunity for a substantial commission on the replacement policy. Of course, the fact that a life insurance agent will be paid for their role in helping to execute a good policy replacement isn’t necessarily a bad thing; unfortunately, though, in many cases it causes the insurance agent to lead with the approach of replacing the policy, instead of looking at the aforementioned options of restructuring or adding more cash first.

Nonetheless, in some cases a replacement may be the only option. A replacement can be especially appealing if the insured has actually had an improvement in health (such that even though he/she is now older, the premiums could be similar or lower), and sometimes it’s possible to replace with a more favorable policy simply because the original one wasn’t shopped aggressively in the first place (i.e., there were already other, cheaper policies available), especially given that mortality tables have improved as medical science has advanced. In some cases, the replacement policy is one that has more flexibility (e.g., going from a whole life policy to a universal life policy), or just costs less to maintain (e.g., a death-benefit-only universal life policy that doesn’t accumulate cash value, to replace an existing cash value accumulation policy, so the new policy can simply be held until death to obtain the tax-free death benefit).

In addition, in today’s “modern” life insurance policies, often it’s possible to get life insurance loan provisions at more favorable rates than “old” policies. For instance, many policies today provide that the policy loan interest rate is simply the current crediting rate plus a “spread” of 0.5% to 1% - which on top of low crediting rates like 3%, means the loan interest rate might be as little as 4%. By contrast, loan interest rates of 6% or even 8% were not uncommon for policies in the 1980s and 1990s. Which means the new replacement policy could be far more sustainable than the original – and help rescue the situation – simply because the loan interest rate will compound more slowly going forward.

Notably, an important caveat of doing a 1035 tax-free exchange to rescue the old life insurance policy with a loan is that it’s essential that the new policy still take on an identical loan. In other words, the exchange should still be for the gross cash value of the life insurance policy with a loan, for a new replacement policy that receives all that cash value and the loan commitment. The reason is that if a policy with a loan is exchanged for a policy without a loan, the elimination of the loan is treated as having received a partial liquidation of the policy, which triggers income tax consequences.

Example. Charlie has a $750,000 universal life policy with a $200,000 cash value and a $150,000 outstanding loan balance (and thus has a net surrender value of $50,000). If Charlie does a 1035 like-kind exchange from his current life insurance policy to a new, smaller policy for “just” the $50,000 of net cash value, he’s actually treated as having exchanged $50,000 of cash value plus receiving another $150,000 of cash to boot, which was used to repay the loan… and that $150,000 of “boot” is taxable as a partial surrender of the policy. To avoid this so-called “boot” treatment, it’s essential that the new policy be a $200,000 cash value with a $150,000 outstanding loan balance, precisely matching the original policy. (The death benefit, however, can be different.)

Fortunately, it is possible to get a replacement life insurance policy with a loan, but such transactions are not standard. Instead, it is necessary to specifically request a version of the life insurance policy that can accept an incoming loan – which at many companies, are dubbed “life insurance loan rescue policies” because they are used for this exact purpose. Companies ranging from Genworth to Zurich, and Voya to Lincoln, all have life insurance loan rescue policies available.

If a replacement policy loan rescue is being contemplated, though, it’s crucial to still thoroughly vet the replacement policy itself – most notably, regarding how the life insurance cash value will be invested, and whether it’s being illustrated at an appropriate rate or not. For instance, the “appropriate” rate to projected an indexed universal life policy is highly controversial in today’s environment, and “over-projecting” the growth rate (i.e., assuming a higher-than-realistic growth rate) could cause the replacement policy to get into trouble in the future, re-creating the exact problem that the replacement policy was intended to avoid! The same caution goes for replacement policy loan rescues that refinance the loan using a premium financing strategy – which can potentially lower the loan interest rate, but can again create ‘unexpected’ problems if interest rates rise (as premium financing loans are typically floating rate) but the life insurance policy’s crediting rate doesn’t keep up (causing the cash value to lag the loan which again can trigger a lapse of the new replacement policy!).

Surrender The Policy Or Sell It In A Life Settlement Transaction

For the life insurance policy that really “can’t” be effectively rescued – at least, not without a substantial cash infusion that the policyowner may not want to make – the last option is to just let the policy go.

The most straightforward way to do this is to simply contact the insurance company and request a surrender of the policy. To the extent there is any positive cash value remaining, the proceeds will be sent to the policyowner. Notably, as with any policy that has a substantial loan, the taxable gain will still be based on the gross cash value (before repayment of the loan), which means it’s possible that most/all of the cash value proceeds will be consumed by the tax liability for any gain. Still, getting at least some cash value out of the policy – to help cover the tax gain – is better than getting no cash value out of the policy at all, by allowing it to continue until the compounding loan drives the cash value all the way to zero. Of course, this strategy is not a good idea if the insured is in very poor health, and there’s a possibility that an actual death benefit payout could occur soon (in which case it’s really worthwhile to try to hold onto the policy, and even put money into it to keep it going until death).

For insurance policies on those who are at least in their 60s (or older), another alternative to consider is a life settlement transaction. A life settlement is the sale of a life insurance policy to a third-party buyer/investor. The virtue of engaging in a life settlement is that in some cases, the buyer will pay more than “just” the remaining net cash value surrender after repaying the loan, which means the person who was going to let the policy go anyway simply gets more cash in his/her pocket. Notably, the transaction is still taxable; nonetheless, a life settlement for an amount greater than the cash value at least gives more dollars to help pay the taxes. And once the buyer takes over the policy, he/she is responsible for the sustaining the loan as well.

A life settlement transaction will be most favorable for an insured who has had a significant adverse change in health, such that the policy is likely to pay out as a death benefit sooner rather than later (and thus why the buyer will pay more); the caveat, however, is that in such situations, it’s especially appealing to keep the policy for that very reason (as if it’s good for the investor, it’s good for the original policyowner, too!).

Nonetheless, for those who just don’t want the cash flow obligation of maintaining the policy given a substantial loan, and are at least in their 60s with some health conditions (which improves the price of the transaction), getting full value from a third-party buyer in a life settlement transaction is a better way to “rescue” the policy’s remaining value than simply surrendering it to the insurance company for its cash surrender value.

Executing A Life Insurance Policy Loan Rescue Still Requires Ongoing Monitoring

Because the reality is that most life insurance policies today have several “moving parts” – from crediting rates and loan interest rates, to dividends on participating policies and more – it’s important to recognize that even after engaging in a life insurance policy loan rescue, it’s still necessary to have a proactive ongoing monitoring process. Otherwise, there’s a risk that a “rescued” policy could take a downward turn, which if not caught and corrected quickly, could just necessitate another rescue in the future if the loan compounds out of control again.

Nonetheless, the “good” news is that a life insurance policy with a loan – even a substantial loan that has been neglected and allowed to compound for years – often can be “saved”, at least partially. Unfortunately, the loan interest itself that has accrued must ultimately be paid, and cannot be avoided. But taking steps to engage in a life insurance policy loan rescue can at least potentially ensure that a depleting cash value doesn’t turn into a forced policy lapse, and a big income tax liability as well!

So what do you think? Have you had to help a client rescue a life insurance policy with a sizable loan? What life insurance loan rescue strategies have you found most useful? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!