Executive Summary

From its start in 1980, the 12b-1 fee was controversial – a distribution charge assessed against current mutual fund investors, that the fund company can use to market the fund to new investors. In other words, the mutual fund got to use investor dollars (rather than its own money) to grow the fund’s assets under management (AUM).

In theory, this use of the mutual fund investor’s own money to market the fund company’s products was supposed to be good for the investor, because it would help grow and scale the fund and bring down its operating expense ratio. However, several decades later, subsequent analysis is finding that while mutual funds that charge 12b-1 fees are successful at incentivizing salespeople to bring in more assets under management, the 12b-1 fee isn’t living up to its promise of helping to scale up and bringing down the expense ratio as the mutual fund grows.

At the same time, the reality is that investor behaviors are shifting as well. A growing number of consumers are purchasing their investments directly, avoiding the 12b-1 fee altogether by eliminating the mutual fund salesperson middleman. And as more and more financial advisors become affiliated with an RIA firm and get paid an AUM fee on an advisory account, the 12b-1 fee is less and less of a driver to incentivize financial advisors anyway.

In fact, the entire shift of financial advisors from being mutual fund salespeople (compensated by upfront commissions and ongoing 12b-1 fees) to operating as actual financial advisors instead (compensated by fees directly from their clients) raises the question of whether the 12b-1 fee is still relevant at all. Especially given the 12b-1 fee’s controversial roots, and the misalignment it creates between who pays the marketing and distribution costs, and who actually benefits from it.

Of course, the reality is that financial advisors, custodians, broker-dealers, and product providers still need to get paid for what they do, which means eliminating the 12b-1 fee still won’t necessarily bring down costs for the end client. Instead, it would likely just shift where and how financial advisors and their platforms get paid. Nonetheless, given the 12b-1 fee’s implicit conflicts, and their declining relevance, arguably it’s time to create a more appropriate pricing structure for the realities of today’s investment marketplace!

The Origin Of The 12b-1 Fee

Rule 12b-1 of the Investment Company Act of 1940 authorizes mutual funds to pay for marketing and distribution expenses directly from the investment assets of shareholders, effectively treating those sales expenses as akin to other operating expenses of the mutual fund.

Because the 12b-1 fee is paid directly by fund investors, the fund’s board of directors must approve a 12b-1 plan before such fees can be assessed (and the board also has a responsibility to monitor the use of the 12b-1 fee over time).

Technically, the 12b-1 fee is comprised of two pieces – a distribution and marketing fee that can be up to 0.75%/year, and a service fee of up to 0.25%/year (for a combined maximum total of 1.0%/year). Accordingly, “A share” mutual funds, which pay a separate upfront sales commission for distribution and marketing, typically have only a 0.25%/year 12b-1 service fee, while “C share” mutual funds that don’t otherwise pay an upfront commission rely on the 0.75% distribution fee + 0.25% service fee = 1% total 12b-1 fee to compensate their salespeople.

Notably, from its start, the 12b-1 fee was controversial. At its core, it imposes an obligation on current investors to pay for the cost for the fund company to market to other people who are not yet investors; in other words, current fund investors pay for the fund company’s salespeople and marketing efforts to get new investors, rather than having the fund company itself pay to grow its business. This is an important contrast to traditional upfront commissions, because those payments do come directly from the fund company (and/or the investor's own dollars directly), not the aggregate of other mutual fund investors. (Notably, “B share” mutual funds allowed broker-dealers to pay brokers an upfront commission, and then recover it over time through the 12b-1 fee, though use of B shares has been in decline.)

In fact, the Investment Company Act of 1940 itself originally banned the use of investor assets to pay for a mutual fund’s marketing and distribution. However, when Rule 12b-1 was first adopted in 1980 under Investment Company Act Release No. 11414, the justification for taking the mutual fund’s marketing expenses directly from shareholders themselves – even though those marketing expenses to grow the fund would enrich the fund company – was that given the underlying fixed costs to run a mutual fund in the first place, adding more investors would allow the fixed costs to be amortized over more investors, bringing the average cost down for everyone, and thus actually benefiting the investors in the long run.

The opportunity to assess a 12b-1 fee to help grow the fund was viewed as an especially important opportunity for smaller/newer mutual funds, that might not have the capital to invest in marketing and distribution themselves, but could use 12b-1 fees assessed on investor assets to grow the fund and ultimately benefit both the fund company (by making the fund larger) and the investors themselves (by scaling the operating costs of the fund and bringing down the expense ratio over time).

The Problem With The Modern 12b-1 Fee

Unfortunately, while in the decades since the 12b-1 fee was first adopted the mutual fund complex overall has grown larger and mutual fund expenses on average have declined, researchers haven’t been able to find much of a link between the existence and use of 12b-1 fees and a subsequent decline in the operating expense ratios of those particular mutual funds.

In other words, if 12b-1 fees “worked”, funds that use a 0.25% 12b-1 fee to grow should eventually see their expense ratios fall by 25bps or more, and overall mutual funds that use 12b-1 fees should end up either being cheaper (as the expense ratio drops by even more than the 0.25% fee as the fund scales its operating expenses), or at least finding other cost efficiencies (e.g., amortizing trading costs over more investor dollars)… both of which would help to improve their returns.

Yet instead, even an SEC study found that mutual funds with 12b-1 fees are becoming much larger, but not cheaper; in the end, they’re just larger funds that are more expensive, by almost the entire cost of the 12b-1, as existing investors continue to pay the marketing costs to reach new investors, which enriches the mutual fund company but not the current fund investors who are paying for it. In other words, the 12b-1 fees investors pay are effective at incentivizing salespeople to distribute mutual funds and grow their assets under management, but there are no operational economies of scale coming back to benefit the investor themselves. Despite the fact that the investor is paying for it.

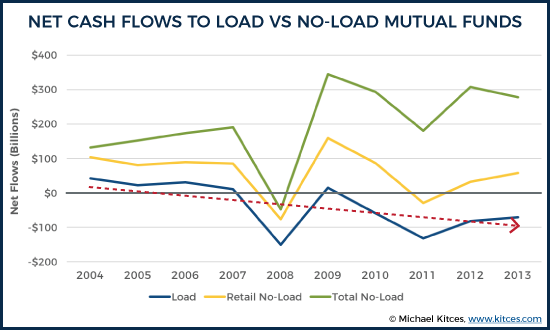

Furthermore, the irony is that even though 12b-1 fees were supposed to help mutual funds grow, in recent years the greatest growth is actually flowing specifically for no-load mutual funds that do not have a 12b-1 fee anyway (e.g., Vanguard). This seems to be driven in part by the growing recognition that since investment costs have such an impact on long-term performance, the best funds to choose are the ones with the lowest expenses (which disproportionately are funds with no 12b-1 fees). But it’s also simply driven by the fact that as investors get more tools to implement their own portfolios, they are effectively cutting out the middleman, pursuing fund share classes that don’t pay sales commissions and assess distribution expenses. At the same time, there’s a shift amongst financial advisors towards independent RIAs, who charge AUM fees but can’t accept 12b-1 fees and instead pursue cheaper institutional share classes on behalf of their clients. Which may only be further accelerated if/when the DoL fiduciary rule come to pass, further winnowing down the number of higher-cost share classes with 12b-1 fees anyway.

Thus, as the chart below from Investment Company Institute (ICI) data shows for the last decade that fund data was available, retail no-load funds (with either no 12b-1 fee, or only a 0.25% 12b-1 servicing fee) have dramatically outgrown the net flows to all loaded funds combined (and it’s even more dramatic when you include all no-load funds, both retail and institutional!). And notably, the data would be even more dramatic if the rapid growth of ETFs, which also have no 12b-1 fees, were included as well!

In addition, the situation is further complicated by the fact that paying “distribution” costs is more complex in the modern investment world. For instance, while 12b-1 fees are paid to brokers who sell a mutual fund, they are also paid to many online investment platforms to offer “No Transaction Fee” (NTF) mutual fund offerings. In other words, rather than having new investors pay the transaction fee to buy the fund (i.e., the mutual fund ticket charge), current investors subsidize the new investor’s cost to purchase by paying the 12b-1 fee to the brokerage firm to make the fund available as an NTF fund. Ultimately, this is a form of distribution cost to incentivize new investors to invest into the mutual fund… but, again, it appears to be more effective at bringing in new investors, than actually scaling up the mutual fund to bring down operating expense ratios for existing investors.

On the other hand, in today’s modern world, some mutual funds use 12b-1 fees to cover more “nondistribution” administrative services that third-party investment platforms help facilitate, including record-keeping and tracking shareholders’ purchases and redemptions (since those transactions are happening on the third-party platform instead of directly with the mutual fund). Arguably, this form of 12b-1 fee is at least less of a distortion, as it’s paid by existing investors to fulfill the record-keeping needs for those existing investors. Still, the fact that some investment companies cover these costs from 12b-1 fees, while others pay the costs directly from the fund company, or simply let the investor pay their platform directly (in the form of transactional or custodial or wrap fees), means that the uneven use of 12b-1 fees can potentially distort the cost of mutual funds in the marketplace.

Are Financial Advisors Really (Still) In The Distribution Business?

From the perspective of financial advisors, the reality is that a huge number of us work in a broker-dealer environment, where our advice is compensated partially or entirely by 12b-1 fees paid out from the investments we recommend for our clients. As a result, the ability to get paid for what we do, through the mechanism of the 12b-1 fee, is a major pillar of how many financial advisors are compensated today. Particularly for those who rely on C share mutual fund trails to generate the “typical” 1% AUM fee as a financial advisor.

Of course, the reality is that there are also a huge swath of financial advisors who work as registered investment advisers, where the RIA generates the exact same net 1% AUM fee from clients. It’s simply paid as a fee from the client directly, rather than a 12b-1 “distribution charge” paid from the fund investor assets. In fact, many in the financial advisor community have suggested there’s little reason to adjust the 12b-1 fee at all, given that it’s simply a means of maintaining advisor compensation parity across the channels (i.e., brokers get a 1% "AUM fee" from 12b-1 fees, and RIAs get a 1% AUM fee from advisory accounts, so it's "about the same").

However, the caveat is that a 1% AUM fee paid to an RIA and a 1% 12b-1 fee paid to a broker are substantively different from a legal and regulatory perspective. A 1% AUM fee is paid by the client, for services to that client. A 1% 12b-1 fee is paid by all the investors to compensate the broker to get new investors.

More generally, the reality is that a 1% AUM fee paid to an RIA is a payment for investment advice; a 1% 12b-1 fee is technically still “just” a distribution charge paid by the mutual fund (or rather, its current investors) to incentivize the broker to sell the product. In other words: a 1% (or any) 12b-1 fee is not (and was not ever) intended to pay for advice. In fact, it’s a requirement under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 that any advice a broker provides to earn a 12b-1 fee must be “solely incidental” to what is primarily just the sale of a product (otherwise, the broker actually would have to register as an investment adviser, and be paid an actual AUM fee for investment advice instead!).

Which means ultimately, if financial advisors really are increasingly moving away from being “salespeople” who get 1%/year commissions, into actual advisors who get 1% AUM fees for investment advice, the shift from 12b-1 fees to AUM fees paid to an RIA may be inevitable anyway. The fact that the DoL fiduciary rule only permits advisors to be “level fee fiduciaries” if they receive level AUM fees (but not level 12b-1 commissions) further emphasizes the advisor and regulatory shift away from 12b-1 fees towards direct client-paid AUM fees instead (and therefore makes the 12b-1 fee less relevant).

Implications Of Eliminating The 12b-1 Fee

So given the declining relevance of the 12b-1 fee in the first place, and the fact that it was never intended to pay for advice, and potentially distorts payments between existing and new fund investors… what are the implications if the fee is eliminated altogether?

From the perspective of financial advisors themselves, the impact could actually be ‘neutral’ for most. Those who rely upon 12b-1 trails for their business model can simply charge an equivalent AUM fee to clients, while doing an internal exchange to convert from a share class of the mutual fund with a 12b-1 fee to an institutional share class instead. Of course, it’s important to recognize that such a conversion would also shift the advisor from being a commission-based broker to an investment adviser representative (IAR) of an RIA (either their own RIA, or a corporate RIA affiliated with their broker-dealer). Nonetheless, given the overwhelming number of financial advisors who are already at least hybrids with both a B/D and RIA affiliation, the transition should be manageable for most.

Ironically, the potential elimination of a 12b-1 fee would likely be more disruptive for the platforms that support financial advisors, than for financial advisors themselves. Most broker-dealers share in the 12b-1 compensation (for both administrative costs, and through their share of GDC grid payouts to brokers), many annuity providers rely on 12b-1 fees from their subaccounts to help supplement the revenue they get from their Mortality and Expense (M&E) costs, and a number of RIA custodians rely on 12b-1 fees to generate a material portion of their revenue (again through either revenue-sharing for administrative costs with the fund provider directly, or by offering NTF platforms that use the 12b-1 share classes to get paid).

Of course, the reality is that as long as broker-dealers, RIA custodians, and annuity products exist and must generate revenue, ultimately the cost must be borne somehow by the end investor. Eliminating 12b-1 fees from annuities will just increase their M&E charges, limiting their payments to broker-dealers will just drive those firms to have advisors charge AUM fees and share in the take from their corporate RIA instead, and if RIA custodians (and direct-to-consumer investing websites) can’t get 12b-1 fees for NTF funds, they may simply end out charging an equivalent wrap fee or custodial fee to the end consumer instead.

Ultimately, though, such a shift would arguably still help better align costs for consumers – as now investors will pay their own expenses, rather than the expenses of fund companies to grow their own profits, and the fund companies can make their own decisions about the benefits of paying for marketing and distribution. And increasing the “saliency” of the costs – making consumers more aware of what they’re paying by charging outright AUM or platform fees – helps consumers better assess whether they’re really getting their money’s worth in what they’re paying for (as research has shown that 12b-1 fees are less salient and may be distorting mutual fund buying decisions). Arguably, that does put more pressure on everyone – from financial advisors to the platforms who serve them – to better justify that their cost is worth the value that it provides. But that’s already true for most independent RIAs and other fiduciaries, who have been growing rapidly in the past decade despite being unable to earn back-end 12b-1 fees!

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that as investors increasingly buy their investments direct, and financial advisors shift from being salespeople who distribute mutual funds to actual advisors who get paid for advice (which might happen to include recommendations on how to implement a portfolio), the relevance of the 12b-1 fee itself is declining, even as 30+ years of its existence has failed to prove it can accomplish its original purpose (to help grow mutual funds in a manner that brings their operating expense ratios down by more than their 12b-1 fees). Ultimately, eliminating the 12b-1 fee won’t necessarily make investing cheaper in the aggregate, as companies and advisors must still be paid for what they do. But it’s time to at least consider a payment mechanism that is more salient, more transparent, and better aligned between who pays the cost and who enjoys the benefits.

So what do you think? Is it time to get rid of 12b-1 fees? Would advisors just charge and equivalent AUM fee if 12b-1 fees were eliminated? Would the impact be larger on custodians and other platforms that support advisors, rather than on advisors themselves? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply