Executive Summary

When we launched, we knew we would be at the cutting edge – or even the bleeding edge – of how financial advisors will get paid for financial planning in the future. What we didn’t know, however, is that we’d also find ourselves at the bleeding edge of regulation over how financial advisors are compensated for fee-for-service advice as well.

Because what we’ve learned in the 3 years since is that the word “retainer”, while relatively straightforward as an explanation to consumers of how services will be paid for – raises significant regulatory concerns. In some cases, we think the concerns are justified; while we’re confident on the value proposition of an XY Planning Network advisor to validate their ongoing cost, there will someday come a day where financial advisors begin to charge monthly retainers but don’t actually do any real work for clients. At that point, consumers become exposed to a new form of “reverse churning”, where similar to abusive AUM fees, the advisor might charge on ongoing fee (or even try to lock clients into an ongoing fee) but not actually provide any ongoing value.

Fortunately, the reality is that with a model like monthly retainers in particular, consumer risk is largely ameliorated by the fact that substantial fees aren’t actually being prepaid in advance (unlike a traditional long-term retainer arrangement); instead, consumers generally have the ability to terminate the advisor at any time, and immediately end what is effectively an ongoing monthly subscription fee they were paying to the advisor. Which is far better than paying an annual retainer fee, and then discovering one month later that the advisor is shutting his/her doors, and that the other 11 months of fees have been forfeited.

Nonetheless, even when paying on a monthly basis, there are still valid regulatory concerns about whether consumers will be protected. Should advisors be allowed to create longer-term retainer fee agreements as well? What kinds of notifications are necessary to ensure consumers are aware of and remember what they’re paying, which in turn helps to ensure the advisor remains held accountable for service and value? What needs to be done to ensure fee billing and the potential access to bank account or credit card numbers that may entail, doesn’t trigger custody of client assets? And how should regulators (and consumers) evaluate whether a fee is “reasonable”, particularly if it is primarily for non-investment purposes and bears no relationship to the size of investment portfolios?

The added complication is that because financial-planning-centric advisors may not manage portfolios at all, they will in practice be regulated predominantly by state securities regulators, which we’ve found over the past several years have quite varying views about the safety (or not) of charging consumers non-AUM fees (and in some cases, different opinions from different regulators in the same state!). In other words, there is little uniformity regarding the above regulatory issues about fee-for-service financial planning from one state regulator to the next. Accordingly, to the extent that the monthly retainer and other fee-for-service financial planning models are gaining momentum, perhaps it’s time for NASAA to consider a Model Rule that sets forth best practices in reasonable regulation and oversight of these new financial advisor business models?

Prepaying Retainer Fees, Audited Financials, and RIA Custody

When a client pays a retainer fee or more generally makes any prepayment of an advisory fee, there’s always some risk that the advisory firm could actually go out of business before it fully renders its services, creating a risk of loss for the client (of the unearned fee).

As a result, the SEC requires that a registered investment adviser who receives a prepayment of more than $1,200 in fees more than 6 months in advance, must provide an audited balance sheet of the business along with Part 2 of Form ADV, in addition to making further disclosures under Item 18 of the ADV regarding any financial condition that “is reasonably likely to impair your ability to meet contractual commitments to clients”. (The requirement was previously a prepayment of $500 in fees more than 6 months in advance, but was increased to a $1,200 threshold in 2010 as a part of the updated Form ADV Part 2 brochure rules issued under Release No. IA-3060.) Notably, in order to trigger the requirement, the fee must be both greater than $1,200 and for a time period more than 6 months in advance; in other words, even a $10,000 fee doesn’t trigger the rule, if the services are expected to be timely performed within 6 months (as then it’s not a “prepayment” of a fee, it’s just a fee for a service that takes time to deliver).

The purpose of these rules is to help protect consumers by at least ensuring they will be aware if there’s a risk that an advisory fee might be prepaid and the advisory firm could go out of business before delivering the services. At least – or especially – if the size of the advisory fee is substantial. Thus why smaller advisory fees (less than $1,200 for more than 6 months) are presumed to be small enough that the client’s financial risk is already limited.

These requirements to obtain audited financials for an advisory firm may seem familiar to some investment advisers, because they’re similar to the so-called Custody Rule of Section 206(4)-2 of the Investment Advisers Act, which similarly requires an audited balance sheet (and an annual random audit) to affirm the integrity of client assets under the adviser’s purview. However, the mere prepayment of advisory fees itself does not actually meet the definition of custody under Release No. IA-2176 (although the ability of an adviser to deduct advisory fees, or other expenses directly from a client’s account does trigger custody with respect to the assets in that account). Instead, the reason the rules are similar is that in both scenarios – where an advisor has custody, or where the client has made a substantial prepayment of fees to the advisory firm – there is an important regulatory protection to making consumers aware of the financial stability of the advisory firm itself.

Retainer Fees – Prepaid Services Or Paying For Availability?

The idea that consumers must be “protected” from those who charge upfront retainer fees – and then might fail to actually deliver the services – is not new. Since the SEC first adopted the “brochure rule” requirements to deliver Form ADV disclosures in 1979 under Rule 204-3, there has been some requirement to disclose to clients any financial risks of the advisory firm itself that they may be exposed to by making a sizable prepayment of advisory fees.

For other professionals like lawyers, the rules often go even further, with most states requiring that lawyers place any prepaid retainer fee into escrow (rather than just holding them in a general business account), and only drawing the fees out of escrow as they are actually earned by the attorney for (hourly) services rendered. To the extent that any retainer fee is not actually “earned” with services rendered – because in essence, it’s simply a prepayment of future hourly fees to ensure the client actually does pay – the unused (or “unearned”) remainder goes back to the client, along with any interest that may have been generated in the escrow account along the way.

Similarly, some state securities regulators in recent years have also issued guidance regarding retainer fees, though in the case of advisors it is sometimes even more stringent. For instance, the Utah Division of Securities has actually taken the position that most retainer fees would be considered “unreasonable advisory fees” and prohibited, at least if they’re nonrefundable or are paying solely for the advisor’s “availability” (without any assurance that advisory services will actually be rendered); notably, a “specific” retainer fee that constitutes a prepayment upfront for a specific advisory service to be delivered over time (where the fee is released to the advisor as services are rendered) is permitted, but only if the prepaid monies are held in escrow (or deposited in a trust account in the client’s name), are used exclusively for advisory services, and the advisor follows certain disclosure requirements (including an annual independently-audited financial statement).

Fortunately, in the case of Utah’s regulatory guidance, there is an important distinction between true “retainer” fees, and simply charging a fixed fee for a given service that may happen to be charged in advance (but can be directly tied to a particular service). Thus, for instance, charging a fixed $3,000 fee upfront for specific advisory services that will be rendered over the coming year is not prohibited (as long as the fee is otherwise “reasonable” relative to services actually being rendered), because it’s not actually a true retainer fee in the first place. It’s simply a fixed fee for fixed services that happens to be payable/paid in advance.

In other words, the key regulatory distinction between a retainer fee and a fixed (e.g., flat, hourly, or projected-based) fee for financial advisors is whether the advisor’s service commitment is open-ended, or details out a specific list of services that will be rendered over time to earn the fee.

Reverse Churning With Retainer Fees Vs AUM Fees

From the (state) regulator perspective, the risk of retainer fees that are not tied to any particular advisory service is that it potentially constitutes a form of “reverse churning” – where the advisor receives an ongoing advisory fee but doesn’t actually do anything to earn the advisory fee. In other words, if churning is where too many transactions (i.e., too much activity) occurs in a client’s account (to maximize the commissions), reverse churning is where too little activity occurs (i.e., not enough actual services rendered or work done to justify the fee that was charged).

Reverse churning has already been on the SEC’s radar screen for several years now, as the industry shifts increasingly towards fee-based advisory accounts while it’s unclear what some advisors are actually doing for those ongoing fees. And arguably, the prospective risk of reverse churning will only get worse in the future under the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, which will likely shift even more commission-based accounts to fee-based advisory accounts, further raising the question of what those advisors actually doing to earn those newfound recurring advisory fees.

In essence, the question is whether the advisory fee, divided by the hours committed for service, constitute a “reasonable” payment for services to be rendered in the first place; an open-ended retainer (e.g., primarily for “availability” of the advisor but no actual assurance of use) is a concern to regulators, because it’s not clear how much time the advisor will actually spend servicing the client (and implicitly assumes that the advisor’s availability alone has no value), which runs the risk that the fee-per-hour is “unreasonable” for the consumer. Which can be relevant regardless of whether the client pays a monthly retainer, annual retainer, or AUM fee; in any of those cases, dollars paid for services not rendered remains a risk.

Nonetheless, a striking dissimilarity is emerging in how regulators handle prospective reverse churning of retainer-style or flat advisory fees, versus reverse churning in fee-based accounts charging an AUM fee.

For instance, imagine an advisory firm that is servicing a $1,000,000 investment account. The client’s portfolio is invested and managed (on a discretionary basis) in a diversified range of passive index funds, which are periodically rebalanced once per year, but generally not otherwise traded (given the passive strategic investment approach). In addition, the advisor meets with clients twice per year to review the portfolio, addresses any other financial planning questions as they arise (with a full financial plan update every 3 years), and is generally available to clients as any other problems arise (e.g., to be a soothing voice in times of market volatility).

We know from industry benchmarking data that a typical AUM fee for this $1M client household would be 1%, which amounts to a $10,000/year fee, and has long since been accepted in the marketplace as being “reasonable compensation” and not excessive.

However, if the financial advisor “merely” charged a $5,000/year retainer fee for the same service – half the price of the AUM fee – the typical regulatory approach would be to scrutinize the exact services rendered to a far greater degree. For instance, an itemized list of services (and associated time spent) might be as follows:

- 2 meetings/year @ 2 hours each = 4 hours

- Meeting prep @ 1 hour each = 2 hours

- Annual portfolio rebalancing = 1 hour

- Due diligence on investment holdings = 2 hours

- Answering financial planning questions throughout the year = 6 hours (if this is not a “plan update” year)

- Availability to provide support in times of market volatility = 2 hours

In the end, the advisor is charging $5,000/year for an estimate of 17 hours of work, or the equivalent of just under $300/hour for financial planning services. Yet while this is not outside the realm of what experienced professionals charge in other professions, in our consulting support with members going through the registration process for state RIAs through XY Planning Network, we’ve been informed by more than one state regulator that “any advisor’s hourly fee in excess of $150/hour will likely be deemed excessive” by their department. In addition, because there’s no actual assurance that the client will receive any financial planning support (since they might not have any questions) and some regulators don’t allow advisors to charge retainer fees for mere “availability”, from the regulator’s perspective, the advisor is only “committed” for 9 hours (for meetings and meeting prep, rebalancing, and investment due diligence) resulting in an even more egregious (at least to regulators) hourly fee equivalent of $556/hour!

Yet, the problem is that this retainer fee advisor may be providing the exact same service commitment as the AUM fee advisor. And the AUM fee advisor is actually charging twice as much for the same service! Yet in practice, the retainer fee advisor’s registration is at risk for being declined for charging “unreasonable” fees given the expected time allotted, while the registration for an advisor simply charging a 1% AUM fee sails through. Even though the advisor charging the retainer fee was actually charging consumers half the price!

Ironically, as I’ve written in the past, charging fixed hourly or retainer fees can make them more “salient”, where the client is more overtly aware of the payments, potentially to the point of causing fee sensitivity. In point of fact, it appears that highly salient fixed and retainer fees don’t impact only clients, but regulators, too!

How Do Financial Advisors Really Spend Their (Billable) Time?

In part, the regulatory disconnect over what is “reasonable” compensation for a fixed fee (hourly or retainer) versus an AUM fee advisor may stem from a general lack of awareness amongst at least some regulators regarding the shifting value proposition (and actual time spent) of the typical financial-planning-centric advisor themselves.

In the “early” days of investment advisers, their primary role was to literally manage investments, and involved a full-time focus on analyzing securities or entire portfolios, and trading them accordingly. There might be some occasional client meetings, a little administrative support work, and some effort required to obtain new clients, but the bulk of the investment adviser’s time was spent directly on portfolio-related activities.

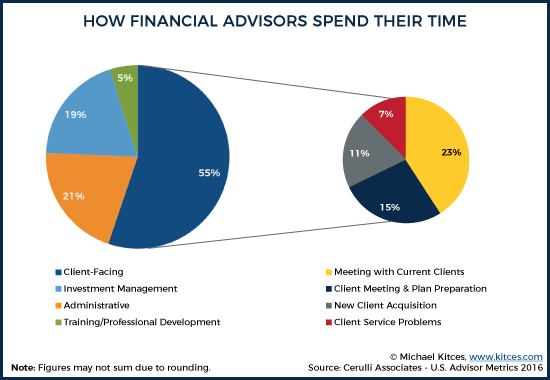

However, a study by Cerulli from 2011 found that the typical state-registered investment advisor (with under $100M of AUM) spends barely 20% of their time actually managing investments; instead, almost 30% of their time is administrative, and another 50% is in client-facing activities. And a 2016 study by Cerulli Associates, The Cerulli Report – U.S. Advisor Metrics 2016: Combatting Fee and Margin Pressure, affirmed that those allocations haven’t changed substantially, with the typical advisor still spending less than 20% of their time on investment management, plus 25% of time on administrative and professional development tasks, and 55% of their time on client-facing activity (and 11% of that time is actually doing business development for new clients, not servicing the existing ones!).

In other words, if the prevailing view of regulators is that clients pay for an investment adviser’s actual time spent on investment management services, then the typical advisor is spending no more than about 400 hours per year on a client’s investment portfolio (assuming a 2,000 hour year). If the advisor has 100 clients, that’s 4 hours per client. If the average client is a millionaire, that’s $2,500 per hour for investment implementation services.

Conversely, if the view is that “client-facing” time is all that really matters in today’s day and age, then a solo advisor who spends 50% of his/her time in client-facing activities is still only spending 1,000 hours of “billable” time, which at 100 clients is 10 hours per client, or $1,000/hour for a millionaire. Yet because so much client-facing activity is responsive and reactive to client requests and demands – and regulators don’t want pricing to be based on availability alone – it potential cost-per-hour to clients could be even higher (and more “unreasonable” from the regulator’s perspective).

Nonetheless, these numbers appear to be an accurate reflection of the marketplace as it exists today, at least or especially for AUM advisors. Recent advisor benchmarking studies have shown that the top 25% most successful solo advisory firms (typically state-registered investment advisers) are enjoying take-home pay over $600,000 per year. Assuming a 2,000 hour work year, that’s $300/hour for every hour of the year. In a more realistic world, where only 60% to 70% of a professional’s time is likely billable (the rest being consumed by internal meetings, business management, conferences/training/education, vacation, etc.), the top solo advisors really are generating a return on advisor time of about $400 to $500/hour.

Yet, as noted earlier, we’ve heard from multiple state regulators raising the question of whether anything above $150/hour is “reasonable” compensation for a fee-for-service advisor. Even as top AUM-based advisors generate as much as 2X or 3X the revenue per hour, albeit with a less salient billing mechanism. Or viewed another way, if regulators fear (and believe they must enforce against) anything more than $150/hour, or a retainer fee in general, may constitute “reverse churning”, is there an even more severe under-enforcement issue currently occurring with the typical AUM-based advisor?

Or alternatively, is the reality that the marketplace actually does find value in a financial advisor’s services – even at these fee levels – and the regulators are simply unaware of what at least a subset of (high-net-worth) clients are willing to pay for the value they perceive and believe they are receiving? Or at least, what consumers are willing to pay to have access to the advisor (as a part of the AUM fee), even if it turns out no advice/meetings were actually necessary at the end of the year? After all, even in the Garrett Planning Network, known for serving middle-class consumers with an hourly fee-for-service model, hourly rates of $150/hour to $200/hour are common – a rate that middle-class consumers are actually already willingly paying, even as state regulators question the cost?

Calling For A NASAA Model Rule – Reasonable Consumer Protections For Retainers And Fee-For-Service Advice?

To be fair, the question of whether more than $150/hour is a “reasonable” hourly rate for financial advice has only been raised in a limited number of states, and certainly not all of them. Nonetheless, as we’re witnessing first-hand in going through state registrations of advisory firms engaged in a “monthly retainer”, or more accurately a financial planning subscription fee model to access a combination of as-promised and as-needed-on-demand advice, there is clearly substantial variability in the treatment of fee-for-service advice from one state regulator to the next.

To that end, perhaps it is time for NASAA to consider a Model Rule, specifically to create more uniformity in how hourly, retainer, and other fee-for-service financial planning advice is regulated, especially with a growing number of industry commentators suggesting that “the AUM fee is toast” and that some form of fixed or retainer fee may be the ‘inevitable’ financial advice business model of the future.

Certainly, as is evidenced by the history of regulation over retainer fees – both in the world of financial/investment advice, and in other professions – some consumer protections are vital. On the other hand, when regulation begins to unwittingly favor old business models over newer ones – especially when the new business model is cheaper than its predecessor – there is a risk of inadvertent consumer harm if regulations fail to adapt, including cutting off consumer access to advice if they don’t have assets to manage, or forcing what is in at least some cases a more expensive AUM model (even if harder to calculate the hourly rate).

Potential areas that a Model Rule for regulation of fee-for-service financial planning advice might address include:

- Risk Of Non-Service. Clearly, one of the most material risks with any form of retainer fee or other prepayment-of-advice fee is the danger than the consumer pays for the service, and the service is never delivered, either because the advisor simply fails to deliver as promised after taking the money, or because the advisory firm itself goes out of business.

Prior SEC guidance has stipulated that consumers are reasonably protected in this regard when the prepayment for services does not extend for more than 6 months in advance, or where it extends further but the dollar amount does not exceed $1,200.

This seems a reasonable rule at the state level as well. Notably, adopting such a rule would grant a clear safe harbor for any financial advisors assessing such fees on a monthly or quarterly basis, as by definition services will never be paid more than 6 months in advance. In other words, the virtue of monthly or quarterly fee-for-service models, over annual fees, is precisely the fact that the consumer has only extended 1 or 3 months of payment, and not 12 months, which inherently limits their exposure (as long as they have the control to terminate their payments and the engagement with the advisor).

Simply put, encouraging shorter recurring billing periods reduces consumer risk over longer prepayment periods (e.g., annual fees for financial/investment advice). And from there, consumers can simply exercise their power to fire an advisor who isn’t delivering – which they are clearly capable of, given that failure to proactively communicate and engage with clients is already the leading cause of why consumers fire their advisors.

- Differentiating Retainers From Fixed Fee-For-Service. As the Utah Division of Securities notes, most advisors who claim to charge a “retainer” fee are actually charging a fixed fee for services that is simply prepaid in advance, and using the term “retainer” differently than the legal profession does.

Nonetheless, some advisors experimenting with new business models for consumers are genuinely seeking to offer more classic open-ended retainer-style models, where “availability” truly is a part of what clients are paying for, akin to a subscription-fee-for-access type of business model. And notably, as discussed earlier, many advisors charging an AUM fee are already operating a form of fee-for-availability business model, with substantial hourly-fee equivalents, but simply charged as an AUM fee on the portfolio (even/especially when the portfolio is passive and no active investment management services are anticipated anyway).

Here, again, a state-level rule akin to the SEC’s guidance regarding a prepayment of fees in excess of $1,200 for more than 6 months in advance seems reasonable. For advisory firms that do charge in excess of these limits, requirements could be put in place that prepaid advisory fees be escrowed and only released as earned. Alternatively, advisory firms could be required to meet certain annual audit and capital requirements – reducing the risk that prepaid consumer fees are lost due to mismanagement and bankruptcy/failure of the advisory firm itself – again akin to the SEC’s existing guidance.

In these scenarios, it is again notable that a shorter and more frequently billing period – e.g., quarterly or monthly fees – could reasonably be exempted from such oversight requirements, since consumers are inherently protected by the fact that the service can be terminated at any time, and consumers haven’t actually paid a substantial upfront fee that is put at risk in the first place. In other words, if a firm charges a $3,000 retainer fee and goes out of business in 2 months, the consumer is at risk to recover the other $2,500; if the firm simply charges $250/month on an ongoing basis, the consumer will have only paid for the actual time period of the engagement (and at worst is only “at risk” for one month’s payments over the next 30 days, not a full years’ worth of payments).

With such protections in place – when unhappy consumers do not face the risk of forfeiting a substantial prepayment of fees in the first place, and can terminate at any time – it is arguably less necessary for regulators to intervene in the determination of whether the services being rendered for the fee are “reasonable” or not in the first place. Just as regulators typically don’t intervene to determine how much “work” the advisor actually is or isn’t doing for their AUM fee, and instead simply force advisors to be clear about what they will provide, and the costs, and allow consumers to choose for themselves.

- Ability To Terminate. Clearly, a key aspect of managing consumer risks/exposure to retainer and other fee-for-service models in the first place, especially when the fees are (automatically) recurring, is the ability of the consumer to terminate the service in the first place.

In the context of a classic (AUM-based) investment advisory relationship, consumers generally have the ability to liquidate and/or transfer funds, and to terminate an advisor at any time. Advisors who do not permit such terminations quickly and easily are subjected to additional disclosure requirements, and in the case of having actual custody of client funds, substantial additional oversight and audit requirements.

In the context of retainer or other fee-for-service engagements, consumers should have a clear ability to terminate the advisor. This would ostensibly include the requirement that consumers remain in control of any recurring fees they are paying to the advisor, either requiring that the fees originate directly under the consumer’s control (e.g., via their own bank account’s “Bill Pay” feature), or that any third-party retainer fee payment system allow consumers to terminate directly without contacting the advisor.

Notably, though, to the extent that some advisors structure their recurring fees as a monthly payment plan for an annual service (e.g., an annual financial advice fee, payable monthly or quarterly with an annual commitment), advisors may need some means to set a reasonable contract period for payment (e.g., an annual contract). In other words, to the extent that an annual service model is payable monthly – but only commits an annual series of services that won’t necessarily be delivered monthly – advisors should not be punished for offering a monthly payment plan to facilitate access to advice. Though where advisors in turn require an annual agreement, clear disclosure requirements should be prescribed for any potential “early termination” fees, and the conditions under which they may apply or be waived.

- Custody. The introduction of substantial annual retainer or fixed fees for services, or even “just” automatically recurring monthly or quarterly advice fees, introduces several custody risks to consider.

The first is simply that if the advisor receives a substantial payment of fees in advance for services not yet rendered, then at a minimum, the advisor should be required – as the SEC already does require – to substantiate that the client is not at significant risk in the event the advisory firm fails as a business, and/or that fees be placed into escrow (which, admittedly, is not currently an industry standard, and for which there is currently limited infrastructure and capabilities for advisory firms).

The second is that the process of establishing a fixed or retainer fee relationship, especially if it is a recurring payment, also may involve the handling of bank or credit card information, and the potential to set (or change) fees without the consumer’s awareness. Reasonable consumer protections might include a requirement that advisors not directly handle any credit card numbers or bank/routing numbers (and that instead the payment information be entered directly into a third-party payment processor), and that clients be required to (pre-)approve both the initial setting, and any subsequent change, to advisory fees over time.

- Transparency & Notifications. The introduction of retainer or other fixed fee models, and especially of recurring fees, brings to the table new forms of “reverse churning” that require at least some consumer protections.

Of course, as noted earlier, reverse churning is already a challenge amongst fee-based advisory accounts, which means regulation really needs to address the issue uniformly across all types of advisory firms.

Key initiatives that may help protect consumers, especially in the context of recurring fee-for-service models, include:

- A requirement that any third-party payment processor or billing include a clear payment confirmation to the client after each payment.

- An annual notification to clients of the ongoing fee they’re paying, cumulative fees paid in the past year, the annualized fee in the upcoming year, and a reminder prompt that they have the right opt-out and terminate the service at any time (or be subject to any annual contract the advisor may apply upon renewal).

- A requirement for the client to be notified of and approve of any change (i.e., increase) in the advisory fee (along with an updated advisory agreement).

- The ability to obtain payment history, and terminate the engagement, without the need to contact the advisor directly.

Notably, clear communication to clients about what they’re paying, and when, will also naturally encourage advisors to communicate what they’re actually doing for their clients, and the value provided. Just as regular client invoices and AUM fee notifications encourage AUM clients to demand portfolio reviews and affirm whether the advisor is adding any value for the portfolio.

- Determining “Reasonable” Fees. The shorter the payment period of an advisory fee, the less at risk consumers are for an advisor who charges “unreasonable” fees, as the consumer always has the option to simply terminate the service.

Nonetheless, advisory firms should clearly be required – as they arguably already are – to specify the exact services to be provided, or at least made available to the consumer upon need. On the other hand, as long as fees are clearly described and are terminable, and services are clearly described, consumers should be able to decide for themselves whether the services are reasonable for the cost, rather than setting an arbitrary benchmark like $150/hour (especially when other advisory firm models already facilitate far higher hourly fee equivalents). Otherwise, direct regulator interventions to set an “appropriate advisory fee” risk unwittingly biasing regulation in favor of more scalable (but potentially more expensive?) AUM fees over an arguably more transparent fee-for-service model.

Similarly, it’s important for regulation to treat different billing and business models reasonably consistently. For instance, some advisory firms are experimenting with retainer fees priced based on income or net worth, which at least one regulator has informed an XYPN advisor is an “unreasonable” fee structure given that it compensates the advisor more for higher net worth clientele than lower net worth clientele. Yet ironically, the advisor could have simply charged an AUM fee, which would have an substantively identical effect, charging the larger portfolio a higher dollar amount of fees than the smaller portfolio for substantively identical investment-and-financial-planning services. And arguably, the AUM fee actually presents more potential conflicts of interest around advice (compared to a pure net worth fee); for instance, the AUM fee discourages advisors from recommending clients pay down debts, compared to a net worth fee.

Similarly, some state regulators have raised concerns about whether a 1%-of-income advisory fee is “unreasonable” because high-income clients will be charged more than low-income clients, despite the fact that a similarly-calculated 1%-of-assets advisory fee is an industry standard (and subject to the same fee-per-client disparities). But again, a percentage-of-income fee doesn’t have the bias of an AUM fee towards saving the dollars versus repaying debts (since the fee based on gross income is the same regardless of how the client actually uses the money).

Notably, in terms of disparities of fees across clients with varying financial capabilities, many industry advocates have already suggested for years that it’s inappropriate that AUM fees are similar percentages for large portfolios and small (resulting in substantially different payments for similar investment services). And in practice, this is already addressed by advisory firms using fee breakpoints and graduated fee schedules, which might easily be adopted in other net-worth or income-based retainer models as well.

In point of fact, this dynamic is also why new advisory firms are attempting to innovate with more flat-fee models built around fee-for-service in the first place – to charge clients more consistently. But again, applying greater regulatory constraints to the business models of fee-for-service advisors while intervening less with AUM models, creates inappropriate regulatory favor for one business model over another (despite the fact that newer business models may actually have inherently better consumer alignment around key issues like debt repayment and serving households that don’t already have substantial assets).

The bottom line: instead of trying to regulate what is or isn’t “reasonable” for consumers to pay across a wide spectrum of needs, incomes, portfolios, and net worths… mandate clear transparency of costs and services to be delivered, and provide for easily terminable services, and let consumers decide (and let advisors innovate and compete, for the benefit of consumers!).

- Recognition Of The Difference Between Investment Advice And Financial Planning. Perhaps the thorniest issue in setting reasonable regulation for fee-for-service advice is the growing breadth of (non-investment financial planning) services that financial advisors provide.

Such services include an ever-growing range of financial planning advice, both in the “generalist” realms (e.g., retirement planning, insurance, tax planning, and estate planning, in addition to the investments themselves as embodied by the CFP Board’s list of Principal Topics), and also a growing range of “niche” services, which may provide even deeper advice offerings (e.g., counseling and financial therapy services, niche expertise for business owners, retirees, professionals in a particular industry, etc.). Arguably, to the extent that these topics don’t actually pertain to investment recommendations, it’s not even clear whether many/most of these services may fall outside the purview of traditional regulation of investment advisers altogether.

But the reason the expansion of advice beyond investments matters isn’t just about determining the appropriate scope of regulatory oversight; more directly, the problem is that consumers are increasingly likely to pay for such services from their income or other non-investment assets, and not necessarily their investment portfolios. Which can make fees look “excessive” relative to the portfolio, even if they’re modest and reasonable relative to the client’s actual capacity to pay, and be difficult for investment-centric regulators to evaluate and benchmark appropriately (if they’re focused too much on portfolios in the first place).

For instance, what is a “reasonable” comprehensive financial advice fee for a young doctor, who has a $7,000 IRA, $150,000 of student loan debt, and an income of $300,000/year, who is about to get married and start a family and has a wide range of questions about budgeting and cash flow, merging household finances, savings strategies for a new house, and career advice about whether to work in an HMO or go into private practice? If the client was willing to pay $250/month for such advice, the total annual fee of $3,000/year would be a modest 1% of his/her income, but a whopping 42% of the investment account. While an investment fee of 42% is clearly beyond excessive (as a standalone investment management fee), what is a reasonable allocation of the fee between pure “investment” and other financial advice services? And is there a point where the advisor’s advice is so beyond the scope of the investment portfolio itself, that the investment advice is negligible and should fall outside of state (or Federal) securities regulation altogether?

- Competency Standards. The last issue that the growth of fee-for-service advice indirectly highlights is whether there needs to be a new competency standard for giving such advice. After all, some have already made the case that the Series 65 actually teaches advisors very little about the competency skills they would actually need to provide ongoing investment advice about a client’s life savings, and the reality is that a Series 65 has virtually nothing to do with comprehensive financial planning advice outside of an investment portfolio.

Thus, is there a point where “advisors” should be limited from holding out as such and offering non-investment comprehensive financial planning services, for fear of making it “too easy” to charge for fee-for-service advice without any actual training or education in providing valuable or relevant advice in the first place?

In other words, if regulators desire to ensure that a consumer will actually receive ongoing advice services to justify ongoing fee-for-service payments for that advice, shouldn’t there be a concern about whether the advisors offering such services even have enough financial knowledge and training to provide such value? Do we ultimately need to get to the point where offering non-investment financial planning advice should have its own testing and competency standards, such as requiring CFP certification?

Ultimately, the bottom line is simply to recognize that the ongoing shift away from product sales and commissions, and towards fee-based advisory accounts, is creating an impetus for some financial advisors to innovate towards new and different business models (both to compete with the surge of adoption in the AUM model, and to reach new segments of consumers the AUM model cannot).

As is the case anytime innovation arrives, it is both an opportunity for consumers to be bettered, and a risk that unscrupulous players will seek to take advantage of consumers. With a prospective surge in retainer, fee-for-service, and other non-AUM advice models, it behooves us as an industry and emerging profession to protect consumers by proactively advocating for reasonable regulation. Hopefully done in a manner that is supportive of positive innovation, rather than stifling it.

So what do you think? Do we need NASAA to consider a Model Rule to address uniformity in how hourly, retainer, and other fee-for-service financial planning is regulated? Should regulators be intervening to determine what "reasonable" fees are? How should we protect consumers without stifling innovation? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!