Executive Summary

Throughout most of its existence, the survival of a financial planner has been built around an "eat what you can kill" mentality; those who could find and bind clients were successful, and those who couldn't hunt for clients successfully didn't survive. Accordingly, most financial planning firms were relatively small businesses, essentially little more than a sole practitioner "hunter" with a handful of support staff.

However, as advisory firms have increasingly shifted over the past decade from a commission-based transactional model to an AUM-based recurring revenue relationship model, the separation of business development of new clients from the servicing of existing clients has created a new role: the employee advisor. And as the number, size, and scale of AUM-based firms has exploded, so too has the number of employee advisors - to the point that, accordingly to the latest industry study, they actually outnumber the owner/partner advisors!

The implications of this shift from hunter advisor to employee advisor is significant. On the one hand, the emergence of multiple tiers of employee advisors is creating the "missing career track" of financial planning, and providing a safe home for advisors who may be wonderful financial planners but terrible at business development. Ultimately, the existence of such career tracks may help to attract far more young talent into the industry. On the other hand, the dearth of young talent available today, coupled with the pace of advisory firm growth, suggests that the talent squeeze will get much worse before it gets better. From the firm's perspective, this may make it increasingly difficult for smaller firms to hire and retain the talent they need to grow and compete. From the perspective of younger advisors, on the other hand, the career opportunities in the coming decade may be nothing short of astounding.

The inspiration for today's blog post is the latest release of the 2013 InvestmentNews/Moss Adams Adviser Compensation & Staffing Study. The Moss Adams study is one of the longest lasting continuous studies of advisory firm compensation and staffing, running continuously since 2002, and provides a fascinating look at not only the best practices of the industry today, but how it has changed over time. And one of the most surprising results of this year's study: for the first time, the survey reported more non-owner professionals than owners, and "employee adviser" is now the most common job description for a staff member of an advisory firm.

The Role Of The Employee Advisor

So what exactly is an "employee" advisor role? Broadly speaking, an employee advisor is one that has varying responsibilities in servicing existing clients for the firm, and may have limited responsibilities in developing new clients of the business, but the advisor is not a partner/owner of the firm.

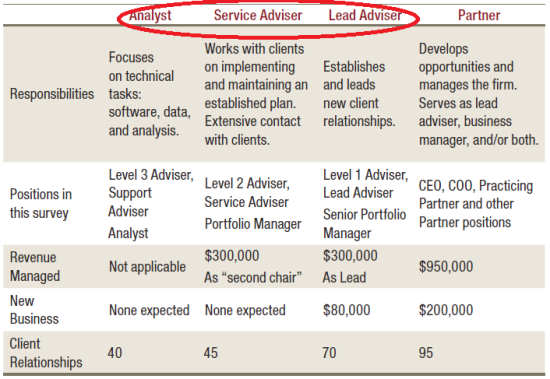

The label captures what has emerged over time as three different tiers of advisors, representing different stages along a long-term career track for the firm: the "support advisor" (also known as an analyst, paraplanner, junior advisor, etc.) who primarily focuses on technical tasks like data analysis and utilizing key software; the "service advisor" who sits as a "second chair" to support client needs until the guidance of a lead advisor; and the "lead advisor" who has primary responsibility for leading existing client relationships, and possibly developing some amount of new business. By contrast, the "partner" advisor, who has an ownership stake, typically has greater business development responsibilities, oversees more revenue, and may have other management-related responsibilities for the firm, in addition to what essentially are "lead advisor" responsibilities of their own. The chart below, from the results of the study itself, shows an example of these advisory tiers, with the "employee advisor" roles circled in red:

Notably, the compensation for these roles is not trivial, either. The median total cash compensation for a lead advisor was $134,000 (with a 3rd quartile as high as $197,500!) after 15 years of experience. Service advisors had a median of about $81,000 of cash compensation with 10 years of experience, and median cash compensation for analyst/support advisors was about $58,000 at 6 years of experience. In addition, the study finds that compensation is rising fastest for those in the lead advisor position - what may still be the early stages of the industry's younger talent shortage playing out with a dearth of supply for lead advisors - and also notably finds that the largest firms, dubbed "super ensembles" (typically $5M+ of revenue) tend to offer the highest compensation levels (in part because they tend to serve the "largest" {highest revenue/professional} clientele).

The Rise Of AUM Firms

Of course, it shouldn't be entirely surprising that larger firms pay greater compensation to employee advisors, for the simple reason that until a firm grows to a fairly substantial size, there simply isn't enough revenue available to fully staff and compensate so many employee advisor tiers.

In fact, the rise of the employee advisor appears to trend directly with the rise of AUM firms themselves. As the Moss Adams study notes, in its first year (2002), the average participating firm had $25 million of AUM and generated $350,000 of revenue to sustain a total of three employees (typically the sole practitioner advisor and some administrative support staff). By contrast, in the latest study, the median revenue of participating firms was almost $2,000,000 and had $200 million of AUM, supported by a staff of 7. While just a few years ago, it was rare to see "ensemble" multi-professional firms, now the study finds nearly 80% of participants operating as ensembles and an emerging new class of "super ensemble" firms with more than $5 million in revenue and/or $1 billion of AUM.

This explosion in the size of firms has in turn allowed for a differentiation of advisor roles that was never possible in the past. When an advisory business is transactional and commission-based, the bulk of the revenue goes to the individual who brought in the business, and as the business starts out every year with no income (until the transactions begin), there was never much opportunity for the business to gain in size and staff. At best, the firm could simply conduct bigger transactions with wealthier clientele, increasing the revenue of the firm.

On the other hand, when an advisory firm is built around recurring revenue - e.g., using AUM fees - there is for the first time a separation of the revenue associated with finding a client from the revenue associated with retaining, servicing, and keeping the client. And simply put, the cost of even a great financial planner to service a client is less than the cost of business development... which means ultimately, the firm can become more profitable by shifting existing clients to service advisors and leaving capacity for the partners/owners to continue to develop new business and add more clients.

And as the Moss Adams studies show, that is exactly what has happened over the past decade. Advisory firms have become increasingly skilled at transitioning new clients to lead, service, and support advisors, separating all but perhaps the largest clients from the senior partners who develop the business in the first place. And as AUM firms continue to grow larger, more and more continue the separation of business development from client service, requiring a growing volume of employee advisors to retain the firm's clients... such that, as noted earlier, there are now more non-owner employee advisors servicing clients than there are owner advisors bringing them in!

Implications For The Future

Ultimately, the ongoing trend towards growing firms with a large cadre of employee advisors seems to be a tremendous positive for the financial planning profession.

First and foremost, the evolution of employee advisors at multiple tiers over the past decade essentially represents the creation of an advisor career track in the profession. While such a track is not always applied consistently at every firm, it is seen more and more commonly as firms grow and begin to standardize their structures. While many have lamented the lack of a career track for financial planners - and to be fair, the number of firms that have such a fully developed career track is still fairly small relative to the total size of the industry - the reality nonetheless is that a professional career track really is emerging.

In turn, the emergence of a career track gives at least some hope for financial planning to finally be able to better attract and retain talent, in a world where there are simply far too few younger advisors coming in to replace those who are retiring out (as Cerulli estimates the headcount for advisors will drop by nearly 10% in the next 5 years). In fact, the InvestmentNews study itself notes very specifically that larger ensemble firms are already beginning to use their fully fleshed out career track as a tool to attract and retain younger advisor talent.

On the other hand, given how far behind the industry already is for attracting young talent and replenishing the pipeline, the question arises of whether this emergence of career tracks will be a way to shepherd young talent into the industry, or a squeeze that emerges for a shortage of it. Notably, the InvestmentNews study finds that median compensation for service advisors actually rose by 8% in the past 2 years, but compensation for lead advisors is up almost 12%, and overall there is still a very significant jump from the average service advisor ($81,000 after 10 years) to the lead advisor ($134,000 after 15 years), suggesting that the real squeeze is for talented advisors who can be fully responsible and unsupervised in managing client relationships. The challenge is that being capable of such responsibilities takes a significant amount of time to train and develop, and is not simply something to be resolved with an influx of new financial planners today. As a result, the danger is actually that firms behind on their hiring and training today will find it increasingly expensive to hire outside lead advisors to come in and hit the ground running, implying that the pressure is on now to begin building their internal pipelines (if they can).

Conversely, the looming talent squeeze for the employee advisor paints a remarkably rosy picture for those "younger" planners today in their 20s, 30s, and even early 40s, who may be working towards or reaching the 10-15 year mark on their careers. If those advisors can develop effective skillsets to not just deliver financial planning to their clients but be responsible for fully managing and retaining the relationship, the career outlook is bright, even if they have no interest in sales and business development. Conversely, for those who do have a business development skillset, the outlook is even better; the median number of years for partner-track advisors to have the opportunity for partnership is a remarkably low 6 years (by contrast, it's typically 8-12 years in the legal and accounting professions), which speaks again to the dearth of available talent and the drive of firms to attract and retain capable advisors when they're found.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: while the roots of financial planning may be in the insurance and investment sales industries, where you "ate what you killed" and every advisor was responsible for business development to survive, the growing size and scale of firms is beginning to separate the skillsets of those who grow the business from those who retain and service it. While it may be true that the greatest rewards will continue to accrue for those who can attract clients and develop business, this separation of duties in an otherwise lucrative industry means a growing number of opportunities for advisors that have nothing to do with sales and new clients and everything to do with servicing and retaining existing clients, and especially for those who can handle the responsibility of managing those relationships. On the other hand, the emergence of such career tracks are far more difficult to flesh out in smaller firms, while the largest are using their career tracks as a tool to attract and retain talent, which means - similar to how marketing scales at larger firms, such that the big firms grow bigger while the small are "stuck" small - there is an emerging risk (or opportunity, depending on your perspective) that the larger firms will win the bulk of the industry's future talent and that small firms may be "stuck" small and struggling to find the talent they need to grow.

Good article. I’d add that employees advisors are more prevalent these days because the dynamics of one doing it on one’s own has changed substantially, so advisors join existing practices. At the wirehouses, for example, the 80s and 90s were offices full of young professionals, sitting in bullpens and cranking out cold calls for much higher sales commission than even any A-share today would provide (read: easier to hit sales numbers). Not to mention, cold calling was actually a worthwhile task. Now, there’s not only the do-not-call registry, but caller ID, and a general leeriness toward sales of any kind. Heck, I am hesitant to answer a call if I don’t recognize the number. And the last point I’d like to add to this fine article is that in those previously mentioned decades, majority of folks who needed financial advice didn’t have an advisor, whereas, today, I’d argue that the opposite is true. In my case, 99% of new clients I get are someone who already has a financial advisor, making it harder today to start out alone like before. I’m aware that the demographics of my town may skew my 99% figure (lots of retirees here), but I imagine it’s similar elsewhere.

Great article, what would be a good resource Or key things to look for to find such a firm that follow this career track?