Executive Summary

The origin of the "safe withdrawal rate" approach was simply to set retirement spending low enough to survive the worst historical sequence of returns we've ever seen; if a future scenario was comparably bad, the retirement portfolio would make it to the end, and if market returns turn out better, the retiree simply has to decide what to do with their "extra" money.

The caveat, however, is that for at least some retirees, the approach of "be conservative upfront, and increase your spending later if returns permit" is not very appealing. Instead, it's more desirable to spend more in the early years, and simply engage in spending cuts if returns end out being less favorable. Except remarkably little research has ever delved into what the best approach is to cutting spending, if it actually does become necessary to make adjustments in order to stay on track!

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our new Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – analyzes safe withdrawal rates based on various dynamic spending adjustments retirees could choose to adopt, finding that small-but-permanent strategies are generally both more effective, and realistically implementable, than large-but-temporary spending adjustments.

Notably, this is different than how many retirees often react when a substantial market decline occurs, where the instinctive response is often to engage in substantial spending cuts for a "temporary" period of time, until the market recovers. For instance, if there's a precipitous market crash of at least 20%, the retiree might trim spending by 20% as well for the next 3 years, until the portfolio recovers. Even if engaging in such spending cuts present serious strains to the retiree's current lifestyle.

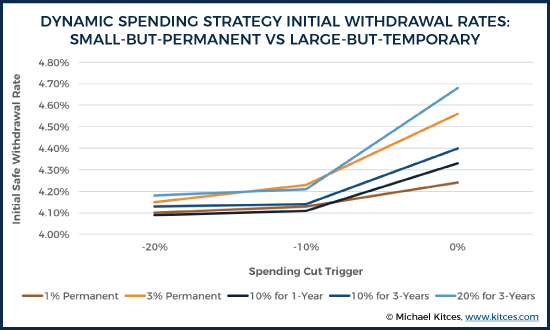

Except as it turns out, engaging in a more rapid series of smaller - but permanent - spending cuts can be even more effective. For example, rather than cutting spending by 20% for 3 years after a market decline of more than 20%, if the retiree simply commits to trimming real spending by 3% (permanently) in any year that market returns are negative - approximately the equivalent of forgoing an inflation adjustment during the down year, and a fairly trivial spending adjustment for most retirees - the safe withdrawal rate rises by almost 0.5% (to more than 4.5%). With the large-but-temporary cut, the safe withdrawal rate only rises by 0.1%, instead.

Ironically, it may feel to retirees that engaging in "small" cuts aren't enough to ameliorate the consequences of a significant market decline early in retirement. Yet the reality is that the cumulative effect of small cuts really does add up - more than engaging in large-but-temporary cuts - in a manner that not only helps keep retirement on track if there's an unfavorable sequence of return, but arguably better aligns to how most retirees spend as well, where real inflation-adjusted spending typically declines in the later years anyway. And of course, if market returns are actually favorable, the retiree not only avoids substantial spending cuts, but enjoys the benefit of starting their retirement spending from a higher level in the first place!

Dynamic Retirement Spending And Safe Withdrawal Rates

Traditional safe withdrawal rate analyses assume a retiree will take steady, ongoing withdrawals from their retirement accounts without deviating from their original level of spending. While there is nothing wrong with this assumption so long as it reflects a particular retiree’s goals, the reality is, retirees can choose to be flexible in their spending as well – and a willingness to cut spending when times are tough means there may be potential to start spending at a higher rate in the first place. For instance, in the event of a recession and a severe market decline, retirees can choose to trim their spending in response, leaving more of the portfolio invested for a future recovery.

At one extreme, a retiree could simply take a certain percentage of a retirement portfolio every year, which would naturally adapt to market volatility (as the same percentage of a smaller account balance after a bear market will produce a smaller withdrawal, and vice versa in a bull market). In fact, mathematically, such a strategy would ensure that the portfolio never actually depletes, as the worse the portfolio performs (and the smaller the account balance gets), the smaller the withdrawals become. The caveat, though, is that translating 100% of market volatility directly into spending volatility may not be tenable for the average retiree, forcing too much change in spending from one year to the next. Most people can only tolerate so much change in their lifestyle in a short period of time.

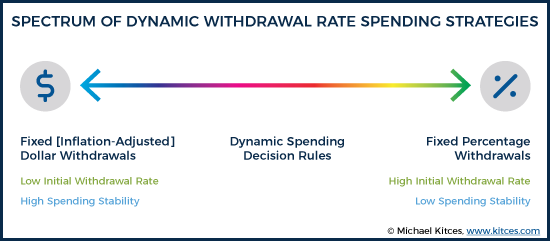

Thus, retirement spending strategies can be considered as part of a continuum, from spending a fixed dollar amount (e.g., 4% of the initial portfolio value, adjusted each subsequent year for inflation regardless of market performance) to spending a fixed percentage of the portfolio each year (e.g., 4% of the then-current portfolio value, recalculated annually). And in between lie any number of strategies that apply at least partial spending adjustments in bad (or good) times, with less rigidity than fixed lifetime real-dollar spending, but more stability than simply recalculating annual spending as a fixed percentage of a volatile portfolio.

In fact, it is this kind of spending flexibility that underlies approaches like the Guyton-Klinger “decision rules” for taking retirement withdrawals. Jonathan Guyton and William Klinger found that initial withdrawal rates could be increased from roughly 4.1% to 5.2-5.6% by utilizing a series of decision rules which determine whether a retiree will make adjustments to their portfolio – such as not taking an inflation adjustment in a given year when the market is down, or cutting retirement income more significantly in bad times (and then making it up later once markets more-than-recovered).

Wade Pfau has published a broad overview of different variable spending strategies and their impact on retirement income and initial withdrawal rates. However, as Pfau notes, in a world of dynamic or variable spending strategies, initial withdrawal rates aren’t entirely meaningful for comparison purposes, since what started out as higher income under one strategy may quickly diminish and be lower under another.

Nonetheless, the point remains that if retirees are willing to be at least somewhat flexible in their retirement spending, a somewhat higher initial withdrawal rate may be feasible. Which is important, as the nature of dynamic spending strategies is only to trim spending when necessary – which means a willingness to be flexible may allow a retiree to start out at a higher spending level and spend more throughout their lifetime (if an adverse sequence of returns never actually occurs).

The Benefits Of Cutting Spending When The Market Declines

One way to assess the relative benefits of dynamic spending is to evaluate the impact that even a relatively simple spending adjustment rule can have on the sustainability of (higher initial) retirement spending.

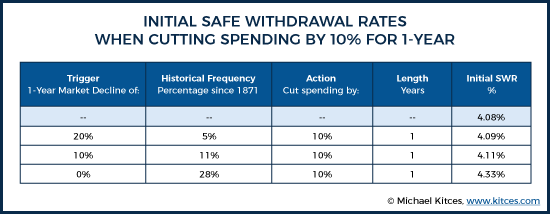

A straightforward starting point is simply to assume that any time a market decline occurs, a retiree will make a temporary but meaningful cut in spending. For instance, what is the impact on the initial safe withdrawal rate if a retiree commits to cutting spending by 10% for 1-year after a market decline of 20%?

The answer, unfortunately, is “not much”. Based on Robert Shiller’s annual data and utilizing a 60/40 two asset class portfolio (S&P 500 and short-term bonds), the initial safe withdrawal rates for 30-year retirement periods based on this adjustment is only an increase in the initial SWR from 4.08% to 4.09%. Clearly, this strategy isn’t buying much more in terms of additional initial spending.

Part of the reason for this is that annual declines of 20% are relatively uncommon – only occurring in about 5% of years since 1871. (Note: because annual Shiller data is being used here, these are only year-to-year 20% declines, and 20% intra-year declines would be more common.) Perhaps this frequency simply isn’t high enough, as retirees would, on average, only experience 1.5 spending cuts throughout retirement.

Consider the same decision rule (cut spending by 10%), but this time the spending cut triggers whenever the decline is greater than 10% or 0%, which would have been experienced in roughly 11% and 28% of years, respectively.

As you can see, this dynamic spending strategy is starting to have more of an impact. Though a 10% decline trigger still didn’t accomplish much (it only lifted the SWR from a baseline of 4.08% to 4.11%), willingness to cut spending by 10% anytime the calendar year return of the S&P 500 was negative lifted the SWR to 4.33%.

Notably, though these thresholds are entirely arbitrary, there is some intuitive appeal to a dynamic spending strategy with a trigger of 0%. If an advisor has an annual review with their client, they simply check to see whether the return was positive or negative for the past year. If the market was up, just continue as planned. If the market was down, then the client takes a 10% (real dollar) spending cut for the next year.

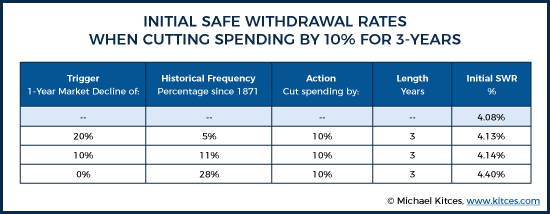

But perhaps we should consider adjusting factors other than the market decline that triggers the spending cut. Perhaps one year simply isn’t sufficient for the market to recover, and a more prolonged spending cut would have a larger impact?

The Impact Of Larger And More Extended Spending Cuts After Market Declines

To analyze the impact of taking more extended spending cuts after a market decline, consider the same trigger points as before, but with the client agreeing to take a 3-year cut in spending anytime a cut in spending is triggered.

Interestingly, this strategy may not buy the retiree as much of an increase in initial spending as expected. There is some benefit to taking a longer cut in spending, but the bulk of the gains in initial SWR come from taking the cut in the year immediately after a decline, as the fact that an extra two years of spending cuts only increases the initial SWR under the 0% trigger strategy from 4.33% to 4.40%.

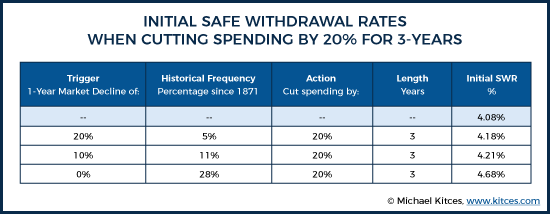

Of course, there’s one more variable we can adjust here, which is the total spending cut. So what happens if the retiree is willing to commit to a 20% spending cut anytime a cut in spending is triggered?

Notably, the larger spending cut does provide a significant boost. A retiree willing to commit to a 20% cut for 3-years anytime the market is down over the past year can actually boost their initial SWR from a baseline of 4.08% to 4.68%. However, the caveat here is given that more than 1-in-4 years since 1871 were negative years, making cuts that last 3-years means that, on average, the client would only not be making a cut roughly 1 out of every 4 years. Therefore, it may arguably be better to frame such a strategy as receiving “bonuses” that occur in times of prolonged market growth (with a lower baseline spending level), rather than subjecting clients to so many “cuts” throughout retirement. For instance, instead of framing these as cuts during bad times, a retiree may effectively start out with a safe withdrawal rate of 3.74% and boost it up to 4.68% whenever the market’s returns were positive for 3 consecutive years.

The Benefit Of Small Permanent Spending Cuts Vs Large Temporary Adjustments

However, there is another way we can adjust these dynamic spending strategies. So far we’ve assumed a retiree makes a spending cut and then returns to the inflation-adjusted path they were previously on, but retirees could instead decide to make smaller but permanent cuts in their spending, which would smooth out consumption and provide less dramatic swings in annual spending.

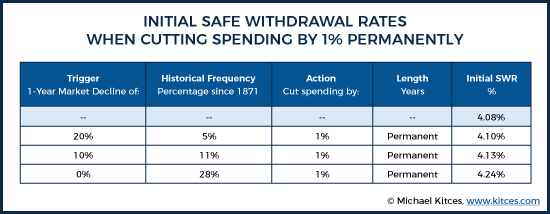

To examine this, we first consider the same trigger thresholds as before (0%, -10%, and -20%), but now, instead of one time cuts, a retiree takes a 1% (real) cut that is permanent over their entire 30-year retirement horizon. In other words, if inflation was 3% for a given year, then if the market was down the prior year, the retiree would only take roughly a 2% increase in spending the next year.

Again, we see effectively no difference at the more extreme trigger thresholds (e.g., 20% market declines), but for a retiree using a trigger threshold of 0%, there is a small but material boost in the initial SWR up to 4.24%. In other words, if a retiree is willing to take a 1% real spending cut any time the market was negative over the prior year, the historical initial SWR is lifted from 4.08% to 4.24%. And while this boost is very modest, the cut in any given year is modest as well, giving a retiree ample time to adjust to a new, lower level of spending.

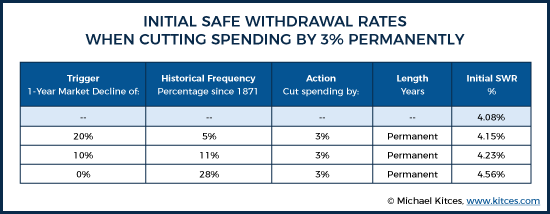

So what happens if we look at a larger permanent cut? Consider the same scenarios but this time with a cut of 3% whenever a threshold is triggered.

Like the other scenarios, there isn't much gain in initial SWR from the more extreme thresholds, but a retiree willing to take a permanent 3% spending cut whenever the market is negative over the past year (roughly akin to forgoing a cost-of-living adjustment after a down year), can boost their historical initial SWR from 4.08% to 4.56%. To put that in context, forgoing a 1-year inflation adjustment has more benefit than engaging in a 10% spending cut for 1-3 years, while arguably being far less disruptive for most retirees. And an initial safe withdrawal rate of 4.56% instead of 4.08% is the equivalent of a 10% increase in real spending on day 1 of retirement.

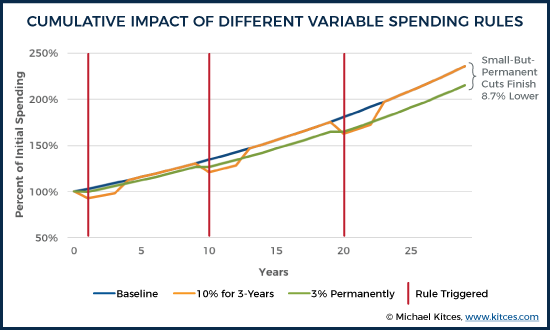

However, it is important to note the difference between short-term cuts in spending (e.g., revert back to the inflation-adjusted path an individual was on prior to the trigger) and cumulative cuts in spending (e.g., cut is permanently made to one’s spending) can be significant:

As you can see in the graphic above, just making one-time cuts of 3% each time a rule was triggered (3 times in this example), results in significantly more long-term spending reductions than a variable spending rule of cutting spending 10% for 3-years after a triggering event (and then returning to “normal” spending). The longer short-term cut may sound more dramatic, and from the perspective of year-to-year spending volatility, it is, but rules that make permanent cuts to spending actually tend to be more substantial when viewed over a long time horizon (which is why they have a greater long-term impact). Of course, the graphic above shows the percentage of initial spending, which is actually beginning at different levels for different strategies, but the point to illustrate is that the retiree experiencing permanent cuts is actually experiencing declining real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) spending in the long run, whereas the baseline retiree is not. Adjusting for the fact that each strategy is beginning at different points, the scenarios associated with a trigger rule that might be expected to generate a reduction about 1-in-10 years (-10% trigger) would suggest that the 3% permanent cut strategy would actually start about 3.7% higher than the baseline strategy but end about 5.4% lower than the baseline.

Nonetheless, the fundamental point remains: engaging in a series of small-but-permanent cuts is actually more effective than large-but-temporary cuts. Such a strategy may feel counter-intuitive to retirees, who, in times of substantial market declines, may actually be inclined to try to cut their spending even more to defend against the risk of depletion. Nonetheless, the fact that markets generally recover within a few years, and that most retirees are still “only” spending around 4% to 5% per year, means small-but-permanent cuts do more to keep retirees on track. Although, at the same time, if the small-but-permanent-cuts approach is to be used, the data suggests that more modest triggers – e.g., taking a 3% cut every time the market’s returns are negative – are necessary, as small cuts that are too infrequent simply don’t do enough to have an impact.

Notably, the higher the initial withdrawal rate due to taking small-but-permanent cuts, the more cuts that would need to be experienced in order to decrease spending back to the "baseline" level, but the lower we would ultimately expect spending to decline below the baseline as well. Though arguably, subsequent small spending cuts are consistent with the research that shows retirees tend to decrease their spending (in real dollars) in later years, anyway. And using a dynamic spending strategy also means the retiree can continue to enjoy greater spending, if/when markets actually do provide a more favorable sequence of returns!

Other Considerations With Flexible Spending Strategies

Portfolio Allocation

One factor influenced by the decision to adopt a flexible approach to retirement spending which is not examined above is the way in which a more flexible spending policy allows for higher equity allocations in a portfolio. In fact, as Irlam and Tomlinson (2014) found in their analysis of recommendations generated by dynamic programming relative to rules of thumb used by advisors, variable spending policies make it more realistic to adopt higher equity allocations, and both variable spending policies and higher equity allocations tend to increase withdrawal rates. However, individuals adopting a higher equity allocation and a cumulative variable spending policy (i.e., small cumulative cuts) would need to pay increased attention to sequence of return risk at the front-end of retirement, as higher initial withdrawal rates that don’t respond quickly to a particularly poor sequence of returns could only exacerbate the effects of sequence of return risk.

Of course, this analysis doesn’t account for the risk tolerance of a retiree and their potential willingness (or not) to accept a higher level of equity allocation or shortfall probability, either of which could suggest a lower or higher initial withdrawal rate. A study by Finke, Pfau, and Williams (2011) found that more risk tolerant individuals may prefer withdrawal rates between 5 and 7 percent once accounting for a guaranteed income of $20,000.

More generally, it’s important to recognize that, for retirees, “risk tolerance” is not only about portfolio volatility, but also about spending volatility, which means those with greater risk tolerance may truly be willing to adopt both more aggressive portfolios and more dynamic spending strategies, while those who are more risk averse may well prefer to both avoid portfolio volatility and seek out more spending-stable strategies.

Of course, coordination with other (non-portfolio) assets could be considered as well. For instance, the use of a HECM reverse mortgage or the use of annuities, such as a QLAC, may influence how flexible a retiree can be in their spending policy.

Retiree Buy-In To Dynamic Spending Strategies

An individual’s goals and preferences will partially drive what types of flexible spending policies they are willing to entertain. As noted above, retirees with more risk tolerance may also tolerate more spending variability (and vice versa for the risk-averse retiree). Similarly, a retiree with a considerable amount of discretionary spending may be more open to making periodic large cuts, given that their spending budget can “handle” it without impairing essential expenses, whereas someone who is just scraping by on essentials won’t realistically be able to make the cuts needed to make the strategy work.

Overall, though, given that most people are assumed to want to “smooth” their consumption over time, needing to make large cuts 25-30% of the time (or more, in some particularly bad sequences of returns) probably won’t be attractive to most retirees. From this perspective, strategies that lend themselves to small-but-permanent (i.e., gradual and cumulative) cuts are likely more realistic to implement. Additionally, given that most retirees appear to experience decreasing spending in retirement, variable spending policies tied to periodic reductions in spending may be an effective strategy to control discretionary spending creep if essential expenses are declining but retirees are just finding ways to spend any extra cash flow. All things considered, the natural urge retirees feel to tighten their belts during a down market may make it an ideal time for an automatic spending cut.

Of course, the flip side to this is that it may be equally appropriate to make upward adjustments in retirement spending once a retiree has the benefit of hindsight to inform their sustainable withdrawal rates in retirement. Particularly given the conservativeness of safe withdrawal rate methodologies (i.e., they are testing against the worst case scenarios experienced to date), there’s reason to believe that many retirees will get further into retirement and have an option to increase their spending, which can be implemented through spending policies such as the Guyton-Klinger withdrawal rate rules and a ratcheting safe withdrawal rate.

Either way, though, a key point of getting retiree buy-in is that retirees themselves must agree to the strategy, and commit to it in advance. This could involve the use of a “Spending Withdrawal Policy” statement that explicitly documents what the spending adjustment triggers would be (any negative return, or only a -10% or -20% drawdown), the magnitude of the spending adjustments (e.g., 1%, 3%, 10%, or 20%), and how long the spending cut will remain in place (permanent or temporary). Ideally, the emerging crop of safe withdrawal rate calculator tools for advisors will also be adapted to illustrate the impact of these strategies, and the relative benefits of small-but-permanent versus large-but-temporary dynamic spending adjustments.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that the ability to make mid-course adjustments to a retirement plan helps – and enough so, that it actually allows for a higher initial withdrawal rate in the first place (possibly starting spending more than 10% higher than a traditional safe withdrawal rate approach!). Yet, even with a plan to engage in dynamic spending, it’s still necessary to adopt a strategy that both has a materially positive impact on the plan and that entails spending adjustments that retirees can actually handle. To that end, it is notable that the approach of “small-but-permanent” spending cuts is actually both more effective at sustaining a retirement portfolio than large-but-temporary cuts, and arguably is more palatable for most retirees to actually implement, too!

So what do you think? Are small-but-permanent spending cuts more effective than large-but-temporary adjustments? Is either more realistic for retirees to adopt? How do you talk to your clients about dynamic spending strategies? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!