Executive Summary

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) feature useful tax advantages that make them a popular savings vehicle. In addition to allowing for tax-deductible contributions, tax-free growth, and tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses (the so-called ‘triple tax benefit’), HSA funds can be invested and allowed to grow for the long term – which has led many people to treat their HSA as a de facto retirement account by saving and investing the funds to be used for healthcare costs in retirement.

One possible outcome of ‘superfunding’ an HSA, however, is that the account owner may not actually use up all of their HSA funds over their lifetime, which can have significant tax consequences. Namely, if the HSA's beneficiary is anyone other than the owner’s spouse, the account loses its HSA status and the entire account value becomes taxable income to the beneficiary in the year of the original owner’s death.

For advisors who recommend HSA-maximizing strategies, then, it’s important to consider the risks of the account owner being unable to use up their funds and to plan for potential ways to quickly draw down the account in the event the HSA owner will not outlive their HSA funds.

One such strategy is to advise clients to keep track of any qualified medical expenses they incur after establishing the HSA – even those that are paid for from funds outside the HSA. Because if the owner ever needs to quickly withdraw funds from the HSA, they will be able to do so tax-free to the extent that they have any previously unreimbursed medical expenses from any point after the HSA was established – which could allow the HSA owner to make a tax-free ‘deathbed drawdown’ of a large amount (or even all) of their account, which would otherwise become taxable income if inherited by the account beneficiary. It’s also important for other parties involved in the owner’s estate plan to be aware of their roles, and to ensure that any funds withdrawn from the HSA are still distributed according to the HSA owner’s wishes.

The key point is that the more that advisors (and their clients) can plan in advance for the contingency of needing to quickly withdraw HSA funds, the more likely they will actually be able to do so. Because although it (hopefully) isn’t likely that any one person will need to do a deathbed HSA drawdown, as more people establish HSAs and accumulate large balances, the odds are that the need to quickly withdraw those funds will become increasingly common – making it all the more valuable for advisors (particularly those recommending HSA maximization strategies) to have tools for doing so while still maximizing the tax advantage of the HSA!

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) hold a special place among the different types of financial planning tools in that they are almost universally beloved by financial advisors. This is because of the so-called ‘triple tax benefit’ that they offer: Tax-deductible contributions (for individuals with eligible high-deductible health plans); tax-free investment growth and income; and tax-free withdrawals at any time to pay for qualified medical expenses.

Furthermore, there’s a lot of flexibility as to when HSA funds can be used. Unlike other tax-advantaged accounts like IRAs, there is no minimum age requirement for withdrawing tax-free HSA funds as long as they are used to pay for or reimburse qualified medical expenses. There are no Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) on HSAs either, meaning the funds can be invested and left in the account to grow tax-free for as long as the owner chooses during their lifetime.

The caveat, however, is that distributions that aren’t used for qualified medical expenses are taxable (with an additional 20% penalty if the owner is under age 65). So in order to receive the full triple-tax benefit of an HSA, there must first be qualified medical expenses for the account owner (or their spouse or dependents) to use the funds on.

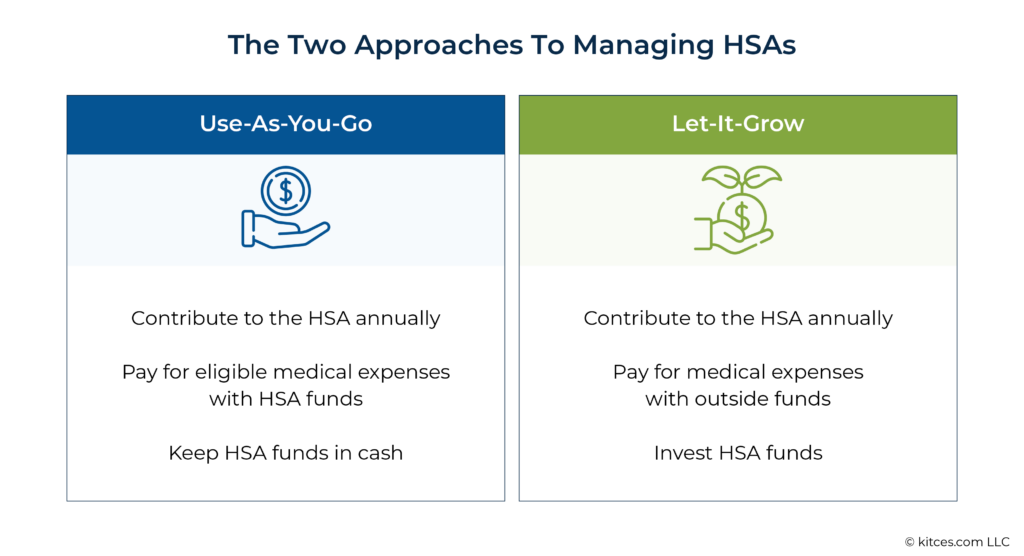

Given these rules, there are two standard ways of using HSAs that have arisen over the years:

- ‘Use-as-you-go’ approach. An individual contributes to their HSA in each year they are eligible, then withdraws funds every time a qualified medical expense comes up. If the medical expenses add up to be less than the contributions, the account balance grows over time; however, if the individual incurs as much or more medical expenses than they contribute to their HSA, the account is emptied out each year.

- ‘Let-it-grow’ approach. The individual contributes to the HSA each year they are eligible as in the first strategy, but when they incur medical costs, they pay for them with funds from outside the HSA, while simultaneously investing the funds inside the HSA to grow in value over time.

Many financial advisors are proponents of the second strategy, i.e., the ‘let-it-grow’ approach. As the thinking goes, leaving HSA funds alone – and crucially, investing them for the long term – is a way to maximize the account’s tax benefits. Because even though the annual contribution limits for HSAs aren’t particularly high ($3,850 for individuals in self-only plans and $7,750 for family coverage in 2023), if an individual starts saving early enough, they can accumulate enough funds via annual contributions and compounding growth to add up to a significant balance at retirement – all of which can be distributed tax-free to pay for qualified medical expenses.

This strategy can make sense given the significance of healthcare costs in retirement. According to the most recent Fidelity Retiree Health Care Cost Estimate, the average retired couple would need to have $315,000 saved at age 65 just to pay for health care expenses. If those ‘average’ retirees were able to pay for the cost of health care with tax-free funds from an HSA, that would help their non-HSA retirement savings go that much farther.

The Downside Of ‘Superfunded’ HSA Balances In Retirement

Given the possibility of paying for some or all of a household’s retirement medical costs with tax-free income, advisors often look for ways to help their clients maximize their HSA funds. By encouraging younger or mid-career clients to enroll in High-Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs), max out their annual HSA contribution limits, and pay any medical expenses from outside funds while investing the HSA funds to grow over time, advisors can help clients accumulate huge HSA balances by retirement.

However, there is a risk in such ‘superfunded’ HSA balances that is often overlooked by those seeking to maximize HSA funds at all costs: What happens when there are more funds in the HSA than the account owner needs to pay for medical expenses in their lifetime? Because as tax-friendly as the rules are for HSA funds during an individual’s lifetime, they can become much more punitive for funds left over after the original account owner dies.

HSA Rules After The Death Of The Account Owner

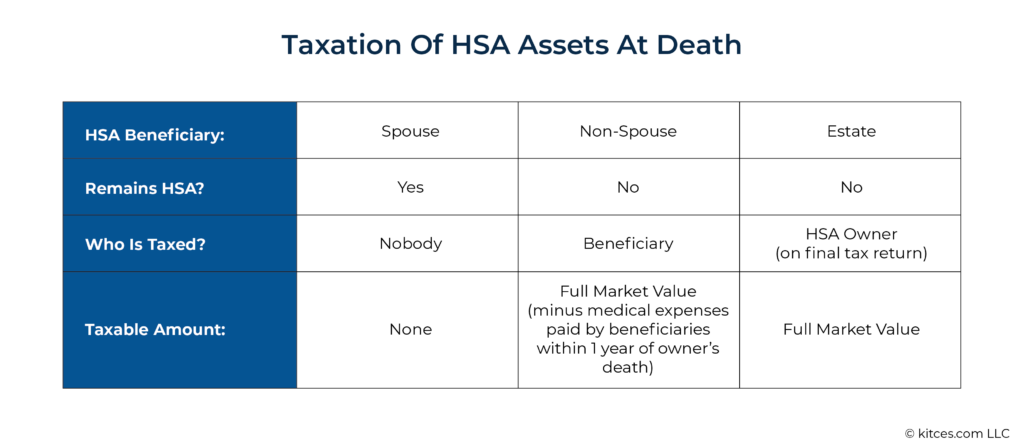

Compared with qualified retirement accounts – for which the SECURE Act introduced a byzantine set of rules for RMDs and drawdown schedules based on the identity and age of different types of account beneficiaries – the tax treatment of inherited HSAs is fairly straightforward. The key factor is whether the HSA’s beneficiary is the account owner’s spouse, anyone besides the spouse, or the owner’s estate.

If the HSA’s designated beneficiary is the account holder’s spouse, the HSA will simply be treated as property of the spouse who inherits it.

Example 1: Henry and Katherine are a married couple. Henry has an HSA with a balance of $50,000 and has named Katherine as the designated beneficiary.

Unfortunately, Henry passes away this year, leaving the entire HSA balance to Katherine. Katherine can now treat the HSA as her own and use the funds to pay for her own qualified medical expenses.

However, if the beneficiary is anyone other than the spouse, the account stops being an HSA, and the entire fair market value as of the original owner’s date of death becomes taxable income to the beneficiary.

The amount taxable to the beneficiary is reduced by any qualified medical expenses for the decedent that are paid by the beneficiary within 1 year after the date of death.

Example 2: Katherine from Example 1 has taken on her late husband’s HSA as her own. The HSA has a balance of $50,000, and she has named her daughter Mary as the new designated beneficiary.

Unfortunately, Katherine passes away this year and leaves the entire HSA balance to Mary. 2 months after Katherine’s death, Mary pays a $10,000 bill for Katherine’s hospice care. The amount that will be included in Mary’s taxable income this year will be $50,000 (the HSA value) – $10,000 (eligible expenses paid within 1 year after the date of death) = $40,000.

Finally, if there is no beneficiary, or if the original owner’s estate is designated as the beneficiary, then the account value is included as taxable income on the original owner’s final tax return (without any reduction for medical expenses paid after the date of death).

Consequently, while HSAs can be a wonderful asset to own during one’s lifetime, they can be a terrible asset to inherit if the beneficiary is anyone other than the owner’s spouse. Being a non-spouse designated beneficiary could mean unexpectedly incurring tens of thousands of dollars (or more) of taxable income – and if the beneficiary already has a lot of taxable income, the taxes paid on the inherited HSA could take up a significant chunk of its value (particularly if it is enough to bump the beneficiary into a higher tax bracket).

Obviously, this doesn’t affect the value of the HSA to the account owner themselves (since by definition they won’t be around to experience the tax consequences of their own demise). However, for HSA owners who care about maximizing the value of what they leave to their heirs – especially when those heirs are someone other than the owner’s spouse - it’s worth considering ways to ensure that their HSA funds are used up during their own lifetimes (or failing that, to distribute the funds in the most tax-efficient way possible before or after the owner’s death).

In the ideal scenario, drawing down HSA funds during retirement would be a slow and steady process over many happy and healthy years (with strategies for doing so likely meriting an article of their own). However, life often has its own plans, and sometimes people may anticipate a long retirement only to find that window compressed into just a few years.

The risk with a superfunded HSA, then, is that a person will build up a large account balance over their working years expecting it to fund many years of medical expenses in retirement – only to have a terminal illness or other unfortunate circumstances cut their life short before they can use those funds up.

Consider this extreme but plausible scenario:

Example 3: Anne is single and started contributing to her HSA in 2004 (the first year HSAs were available) at age 46.

She has maximized her contributions every year since then (including $1,000 annual catch-up contributions starting at age 55) but pays for her medical expenses with outside funds so that she can keep her HSA funds invested at a 6% compound growth rate.

In 2023, at age 65 – after 20 years of contributions – Anne retires and now has over $136,000 in her HSA:

Shortly after her retirement, Anne begins to experience recurring headaches. She goes to her doctor, and after several tests she is diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor. Unfortunately, the doctor estimates that she has only 6 months to live.

The sole beneficiary of Anne’s HSA is Elizabeth, her 30-year-old daughter who is a lawyer. Because she is a non-spouse beneficiary, she will pay taxes on any HSA funds that she inherits at her own marginal tax rate.

If we assume Elizabeth’s marginal Federal tax rate is 32%, then inheriting the entire account would result in $136,000 × 32% = $43,520 in Federal taxes, plus any state taxes she might owe.

In the example above, unless Anne has qualified medical expenses that can be used to withdraw her HSA funds tax-free (which she may or may not depending on the severity and treatment options for her illness, as well as the quality of her health insurance), she essentially has two options: Either withdraw the HSA funds as nonqualified distributions (which would make the withdrawals taxable to her, though not subject to the 20% penalty tax for nonqualified early distributions because she is over age 65), or leave the account to pass to her daughter Elizabeth after her death (which would make the funds taxable to Elizabeth at her own marginal rate).

In this case, the decision would generally come down to who has the lower marginal tax rate: For example, if Anne’s marginal rate is 22% and Elizabeth’s is 32%, it would make more sense for Anne to withdraw the funds while she is still alive and pay tax on them at her own (lower) marginal rate. However, this would still result in losing nearly a quarter of the account’s value to taxes!

When ‘Deathbed Drawdowns’ From HSAs Can Be Tax-Free

As the above example shows, the tax consequences of inheriting an HSA can be significant for a non-spouse beneficiary, especially when the original HSA owner has accumulated a lot of savings but doesn’t live long enough to use them.

One alternative would be for the HSA owner to take a full distribution of the account balance while still living – but that won’t necessarily help much, because if there are no qualified medical expenses to go along with it, the distribution would be fully taxable to the owner (plus a 20% penalty tax if the owner is under age 65).

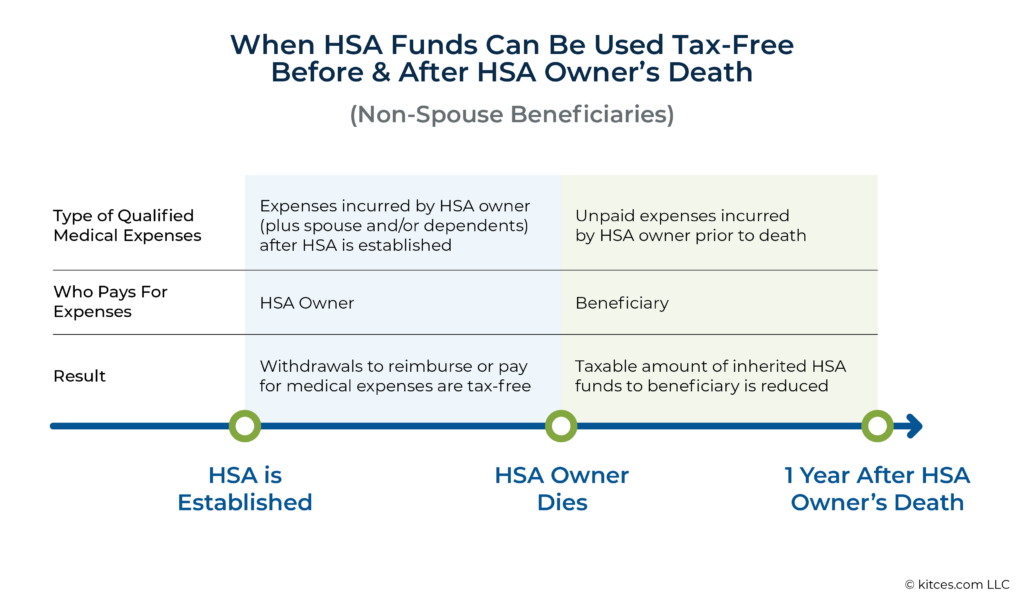

The only way to distribute HSA funds tax-free is by using them to pay or reimburse the owner for qualified medical expenses; the law (specifically IRC Section 223) doesn’t budge on that. However, the HSA rules do allow for much more flexibility in the timing of when expenses are incurred. Specifically, any expenses incurred between the establishment of the HSA and the date the owner dies – and which were not previously reimbursed or deducted on the taxpayer’s Schedule A – are eligible for reimbursement at any time between the date the expense was incurred and the death of the HSA owner.

Example 4: Edward established and started contributing to an HSA in 2008. In 2010, he had dental work done that cost $10,000, which he paid for out-of-pocket from funds outside the HSA.

Now, in 2023, Edward takes a $10,000 distribution from his HSA to reimburse himself for his medical expense from 2010.

Even though 13 years has elapsed between the dental work in 2010 and the reimbursement in 2023, the distribution can be excluded from Edward’s taxable income because it is a qualified medical expense that (1) occurred after the HSA was established, and (2) was not previously reimbursed or deducted.

The upshot of these rules is that anyone with accumulated HSA funds can make withdrawals for whatever reason to the extent of all of their unreimbursed, undeducted, qualified medical expenses that were incurred after establishing their HSA.

In other words, those who have spent years paying medical expenses with funds from outside their HSA while leaving the HSA to grow in value may have effectively built up a large balance of unreimbursed expenses which they can use to justify tax-free withdrawals from their HSA at any time.

If the HSA owner experiences a rapid decline in health, then, they may be able to immediately withdraw a large chunk (if not all) of the HSA’s value tax-free – i.e., a ‘deathbed distribution’ – from the HSA to reimburse themselves for past medical expenses, thus eliminating a great deal of the potential tax burden that would otherwise be passed to their beneficiary.

Example 5: Charles is 60 years old and has spent 20 years saving funds to his HSA, whose balance has grown to $150,000.

Over those 20 years, Charles has also spent an average of $4,000 per year on medical expenses, adding up to $80,000 total. He has paid for all of these expenses out-of-pocket and has neither reimbursed himself through HSA withdrawals nor included the expenses as itemized deductions.

After a brief illness, Charles is in failing health and is not expected to live much longer. His brother James is the sole beneficiary of his HSA.

Because Charles has $80,000 of qualified medical expenses that were previously incurred and paid for (but not reimbursed), he can distribute $80,000 tax-free from the HSA while he is still alive. The remaining $70,000 passes to James after he dies, and that value becomes taxable to him.

Assuming James has a marginal tax rate of 24%, the tax on the $70,000 that passes to him is $70,000 × 24% = $16,800. Whereas if Charles hadn’t distributed the $80,000 tax-free before his death, making the entire $150,000 taxable to James, the tax would have been $150,000 × 24% = $36,000.

In other words, by withdrawing from his HSA to the extent of his prior unreimbursed medical expenses, Charles has saved $36,000 − $16,800 = $19,200 in tax – or more accurately, he has saved his brother James that amount, who is ultimately the recipient of those funds.

HSA balances are set to balloon in the coming years with the increased popularity of the ‘let-it-grow’ method of saving. According to HSA investment solutions provider Devenir, invested assets in HSAs grew over 6X, from $5.5 billion to $34.4 billion, between 2016 and 2021. And as HSA owners invest more assets in their HSAs, the value of using prior unreimbursed medical expenses to make tax-free withdrawals will also increase. For an inherited HSA big enough to bump a beneficiary into a higher tax bracket, the value can increase even further.

Nerd Note:

People occasionally move funds from one HSA to another, or stop contributing and empty their HSA of funds before restarting contributions later on. How does this affect the ‘establishment’ date that dictates the start date for qualified medical expenses?

IRS Notice 2008-59 states that, “If an account beneficiary establishes an HSA, and later establishes another HSA, any later HSA is deemed to be established when the first HSA was established if the account beneficiary has an HSA with a balance greater than zero at any time during the 18-month period ending on the date the later HSA is established.”

In other words, as long as there are funds in the first HSA within 18 months of the date the second HSA is opened, then the second HSA is considered to be ‘established’ on the date the first HSA was opened. Which makes a decent argument for never entirely draining an HSA of funds, because if the owner ever becomes eligible to contribute to another HSA in the future, they will get to keep the earlier HSA’s establishment date as long as it has at least some money in it – even just $1.

Special Rule For Expenses Paid By HSA Beneficiary After Original Owner’s Death

There is one other way that a non-spouse beneficiary can avoid being taxed on the full value of an inherited HSA. IRC Section 223(f)(8)(B)(ii) allows for non-spousal beneficiaries of HSAs to reduce the taxable value of the HSA by the amount of any qualified medical expenses that were:

- Incurred before the date of the decedent’s death; and

- Paid by the beneficiary within 1 year after the decedent’s death.

In other words, expenses like hospice care or emergency room bills which were unpaid as of the HSA owner’s death may be used to reduce the amount of the HSA that becomes taxable income to the beneficiary, but only if the beneficiary pays such expenses within 1 year.

Example 6: William was the designated beneficiary of his father’s HSA. When his father passed away in January, the HSA had a total of $100,000.

In February, one month later, William received a bill for $20,000 from the hospice facility that cared for his father before he died.

If William pays the bill within 1 year of his father’s death, the amount of the HSA that is taxable to him this year is $100,000 – $20,000 = $80,000. If anyone else pays the bill, or if William waits until next February to pay it (i.e., more than 1 year after his father died), the full $100,000 account value will be included in his taxable income for this year.

Three points are worth emphasizing here.

First, only non-spouse beneficiaries receive this treatment. When a spouse is the designated beneficiary, they take over the HSA as their own in a non-taxable transaction, so there is no income to exclude. Additionally, this option is not available when the decedent’s estate is the beneficiary of the HSA (or when the decedent never designated a beneficiary to begin with).

Second, only expenses that are paid by the (non-spouse) beneficiary may be excluded. If an HSA owner does have a non-spouse designated beneficiary, it’s critical that the beneficiary is aware of this rule so that they know to pay any of the decedent’s unpaid medical bills themselves to reduce the amount of the HSA that will be taxable to them, rather than having someone else make the payment and negate the tax benefit to the beneficiary.

Third and finally, this provision only applies to expenses that were incurred but not paid before the decedent’s death. Any amounts that the HSA owner incurred and paid themselves before death – and thus had ‘available’ to reimburse themselves for while they were still alive – are not excludible by the beneficiary. Once the owner passes away, the opportunity to use any expenses that they could have used to reimburse themselves from their HSA – but didn’t – are gone forever.

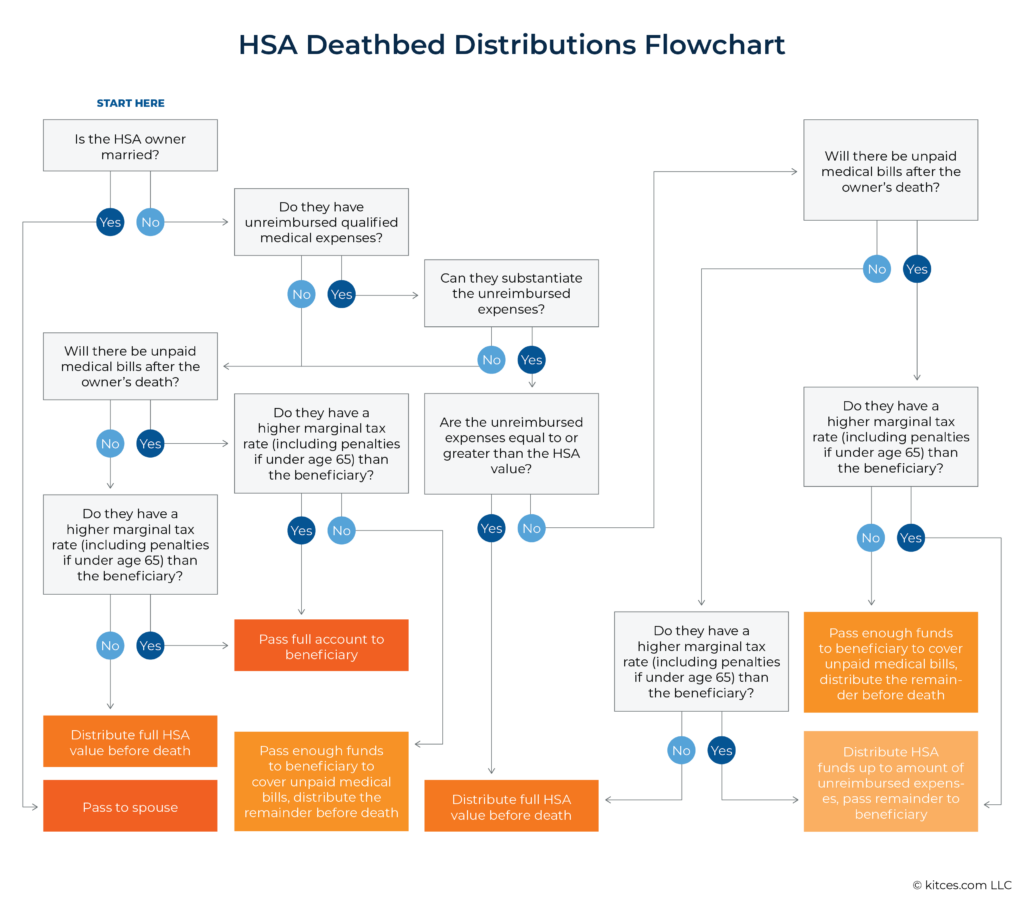

The graphic below visualizes how these rules work for non-spouse HSA beneficiaries:

Recordkeeping Rules

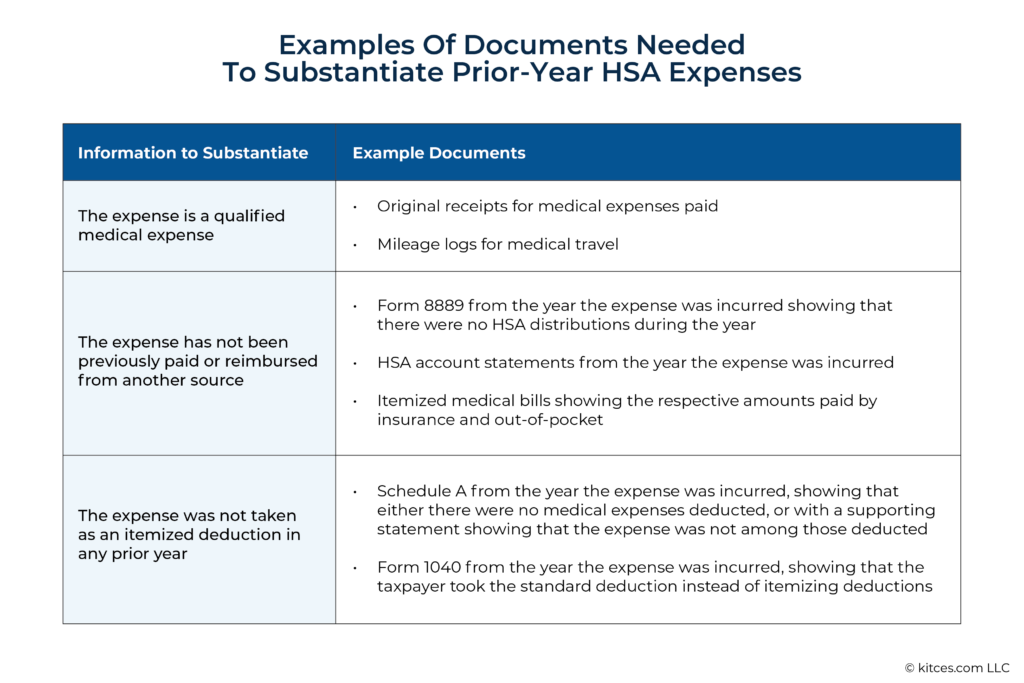

As noted earlier, there are two caveats to the rules allowing HSA owners to reimburse themselves for qualified medical expenses any time after the establishment of their HSA:

- The expense cannot have already been reimbursed by another source (such as insurance, an FSA, or previous HSA distributions); and

- The expense cannot have been taken as an itemized deduction in any prior tax year.

IRS rules require taxpayers to be able to substantiate that any reimbursements from their HSA for qualified medical expenses in past years fulfilled those two requirements (as well as the fact that they were qualified medical expenses to begin with).

Specifically, IRS Notice 2004-50 states that:

…[T]o be excludable from the account beneficiary’s [i.e., the owner’s] gross income, he or she must keep records sufficient to later show that the distributions were exclusively to pay or reimburse qualified medical expenses, that the qualified medical expenses have not been previously paid or reimbursed from another source and that the medical expenses have not been taken as an itemized deduction in any prior taxable year. [emphasis added]

In other words, taking HSA reimbursements for a prior-year expense requires holding on to the documents necessary to substantiate the expense from the year the expense was incurred until the year the reimbursement is made, plus the statute of limitations for the assessment of additional tax (generally the later of 3 years after the due date of the return [or the date the return was filed, if later] or 2 years from the date the tax was paid).

Which documents should taxpayers retain to reimburse prior-year HSA expenses? Since there are 3 pieces of information to substantiate (that the expense was a qualified medical expense, that it wasn’t previously reimbursed, and that it wasn’t taken as an itemized deduction), there may be several documents needed for any given expense, including:

- Receipts and medical travel records to substantiate qualified medical expenses;

- Tax records (e.g., Form 8889), HSA account statements, and itemized medical bills to prove no prior payments or reimbursements were made; and

- Other tax forms (e.g., Schedule A, Form 1040) to prove that expenses were not previously deducted.

Below are some examples of documents that could be used to substantiate HSA distributions for prior year medical expenses:

Executing the Deathbed Drawdown of an HSA

Putting these rules together, it’s possible to outline a strategy for how an HSA owner can draw down their account in a very short amount of time to avoid the entire account becoming taxable income to their beneficiary upon the owner’s death.

The first step is simply to ask: Is this a priority? There could be many other things competing for attention in a situation with a client close to death: other assets to be moved, estate documents to review and update, family members to bring up to speed, etc. If the HSA makes up only a small portion of the client’s overall assets, deciding how much to draw down (and tracking down all the supporting documents for doing so) could easily become a time sink at the expense of other, more valuable tasks. However, it’s just as important not to overlook the client’s HSA entirely, since doing so might prove costly if the HSA generates a huge unexpected tax bill for the beneficiary.

For advisors, it’s important to view the client’s HSA in the context of the client’s entire financial picture to decide if the HSA’s total impact on how their assets are distributed makes it worth taking action. If the individual has $50,000 in their HSA and a total estate of $100,000, it may be well worth taking the time to distribute the HSA; conversely, if they have $100,000 in the HSA and a total estate of $10 million, there may simply be too much to do – with many more dollars at stake – in the time available to worry about the HSA.

The second step is fact-finding, and answering some key questions that will help guide the drawdown strategy:

- Does the client have previous medical expenses that are eligible to be reimbursed (and do they have the supporting documentation required to do so)?

- Who is the HSA beneficiary, and would they pay higher taxes from inheriting the HSA than if the owner were to withdraw the entire account themselves?

- Is the HSA owner incurring medical bills (such as for treatments or palliative care) that the beneficiary would be able to pay after the owner’s death to reduce the amount of the HSA that will become taxable income?

The third step is going through the possible scenarios. If the client has enough unreimbursed medical expenses to empty their entire HSA tax-free, then it would probably make sense to distribute the full account value. But if they don’t, they may have multiple options (e.g., distributing the remaining [unqualified] funds versus leaving them to pass to the beneficiary) depending on various factors.

The flowchart below can help with making the decision of what actions to take based on the client’s circumstances:

Given the potential time constraints involved with rapidly drawing down an HSA, there may be scenarios where it makes the most sense to withdraw the entire account first, and sort out how much could be treated as a tax-free reimbursement for prior medical expenses after the fact. This is because the funds need to be withdrawn while the owner is still alive in order to be treated as a reimbursement at all, while figuring out how much of the withdrawal can receive tax-free treatment doesn’t need to be done until filing the owner’s final tax return. For instance, if an HSA owner knows they have unreimbursed medical expenses but can’t immediately find the supporting documentation for them, it might make sense to distribute the HSA anyway, since those documents aren’t actually needed until the tax return is filed.![]()

![]()

![]()

Nerd Note:

Practical Considerations

A person facing imminent mortality will likely have more pressing things on their mind than properly executing a withdrawal from their HSA. Depending on the situation, they may not even have the capacity to pull together the necessary information to coordinate any HSA transactions. But for many people, it’s still of great importance that their assets are distributed in the way they intend after they are gone – that’s why people create estate plans and often go to great lengths to ensure that taxes won’t eat up a large chunk of those assets (even though they won’t be around to use them themselves).

The same principle holds here: The difference between drawing down a large HSA balance in a tax-efficient way versus leaving it to a non-spouse beneficiary or an estate could equate to tens of thousands of dollars in taxes – easily more than the advisory fees that many clients pay each year – which ultimately can make a material difference in how much of the clients’ assets go to the people they want them to go to.

Financial advisors can play a key role in helping to ensure that their clients’ wishes are carried out, even when that isn’t what may be at the top of the client’s mind at the moment. But doing so requires keeping some practical considerations in mind.

Advance Planning

When a person starts building up their HSA funds, the chances aren’t high that they will one day need to rapidly distribute the account before death. But it is still a risk, and one that those who intend to accumulate large HSA balances should be aware of.

Advisors are increasingly recommending strategies for their clients to superfund their HSA as a supplemental retirement account, even starting as early as young adulthood, which could result in HSA balances in the hundreds of thousands or even millions by retirement. Basic probability dictates that at least some of these people won’t live long enough to fully use their HSA funds. So advisors who recommend strategies to maximize HSA funds would also do their clients a service by helping them plan for the contingency that they will need to make a large distribution all at once lest they leave the account to a non-spouse beneficiary (and effectively, a large chunk of it to the IRS).

To start, this means ensuring the person keeps all information related to their medical expenses, including the documents needed to substantiate HSA expenses as highlighted earlier. This could be as simple as setting aside a folder in a filing cabinet for receipts and supporting documents, though people like me who are averse to accumulating stacks of paper receipts might prefer to scan the documents and upload them to a cloud storage program (e.g., Google Drive, Dropbox, or OneDrive). Advisors who use a digital file-sharing solution with their clients like RightCapital Vault can help clients set up a folder and make organizing medical expense information a part of the annual planning process (e.g., when reviewing the client’s tax returns) – which has the advantage of keeping the information where the advisor can access it in the event they do need to assist with a later deathbed distribution from the HSA.

Practically, many people aren’t willing to log every single qualified medical expense, along with supporting documentation, for the relatively minor probability that they will need to reimburse themselves for those expenses sometime down the line. That’s OK, and with qualified expenses encompassing everything from doctor visits to bottles of aspirin to tampons, at some point the work of tracking minor expenses makes it a poor return on the hassle involved. Such little expenses might add up over time, but it’s the medical bills of hundreds or thousands of dollars that can make a much bigger difference in the end.

Each individual can decide where the line is for them, but at a minimum, they should keep documents for major medical work with high out-of-pocket costs (including eye and dental work, which often isn’t covered by insurance, and transportation and lodging costs for medical-related travel).

Estate Plan Coordination

As noted earlier, an important practical consideration for a person experiencing a rapid decline in health is that they may not have the capacity to execute a deathbed drawdown of their HSA by themselves. And because the strategy most likely applies to those who don’t have a spouse to designate as their HSA beneficiary (since presumably in that case the HSA would be left to the spouse to take over tax-free as their own), it’s important to ensure that someone else other than the HSA owner – perhaps the HSA’s designated beneficiary or another trusted person – understands how to carry it out according to the owner’s wishes.

Ideally, the way to do this would be to coordinate the strategy alongside the other elements of the HSA owner’s estate plan. For example, the person could include a statement along with their living will or advance medical directive, such as the following:

In the event that I am likely near death and the balance of my Health Savings Account exceeds $XX,XXX (after subtracting the costs of my end-of-life medical care), I authorize [authorized person] to fully distribute the account and deposit the proceeds into [desired account].

There are two key points to emphasize here.

First, family members or other individuals who are involved (e.g., the designated beneficiary of the account and/or the person authorized to distribute the account) should be made aware of their roles. They don’t need to have every step of the process memorized, but at a minimum, the financial advisor or estate planning attorney should have a means to contact them to give them guidance in the event they need to fulfill their role.

Second, distributing the HSA into a different type of account will have other estate planning implications. For example, if the HSA were distributed into an account with a different beneficiary from the HSA, those assets might not ultimately go to whom the original HSA owner wished. Advisors, estate planning attorneys, and other representatives of the HSA owner can work together to ensure that the owner’s wishes are still being fulfilled regarding how their assets are distributed.

Finally, if there is no preexisting estate plan, it becomes much more difficult to execute a deathbed drawdown of an HSA. Even if there is someone other than the HSA owner available to execute the withdrawals, a lack of any statement making the owner’s wishes clear leaves it pretty much up to guesswork by those doing the drawdown as to whether it is really in accordance with those wishes. This underscores the importance of planning in advance to ensure the HSA owner’s intentions, and the roles and expectations of others involved, are clear to all beforehand.

HSAs can be a wonderful tool to save for retirement medical expenses in a tax-efficient way. But going all-in on maximizing the value of an HSA – while ignoring the potential consequences of those funds going unused during the owner’s lifetime – risks saddling a non-spouse beneficiary with a surprise tax bill that can eat up a significant chunk of the asset they inherited.

For financial advisors, the key point is to ensure that clients are aware of these risks when planning to superfund their HSAs. By keeping track of any medical expenses incurred by the HSA owner, their spouse, and their beneficiaries – and keeping the records supporting those expenses in an easy-to-locate place – it’s possible to have an insurance plan at the ready to make immediate tax-free withdrawals whenever the (hopefully rare) need arises.

Good article with good cautions for estate planning.

I am 62 and have > $100k in an HSA. My assumption is that I should think of my HSA for which I have historical medical expenses in a similar manner to a Roth IRA. Thus, when I am considering withdrawing from my Roth IRA, I should withdraw from the HSA funds for which I have documented historical medical expenses first. This would reduce the funds in my HSA which would potentially be taxable to my beneficiary.