Executive Summary

As the U.S. stock market has, on average, outperformed international equities over the last 15 years since emerging from the Great Recession of 2008, many investors argue that international diversification is a poor allocation of dollars that would otherwise be earning more in the U.S. market. The outperformance of U.S. stocks has led to the favoritism of ‘local’ investments over international ones through behavioral biases (e.g., recency bias and the tendency to confuse the familiar with the safe) that have swayed investors (and some advisors) away from international diversification entirely. However, despite recent market trends, there is a legitimate case to be made for international diversification – starting with the basic tenet of investing that past performance does not promise future returns.

In this guest post, Larry Swedroe, head of financial and economic research at Buckingham Strategic Wealth, discusses why many investors tend to fall prey to recency bias, and explains why global diversification – and keeping short- and long-term results in the right perspective – remains a prudent strategy.

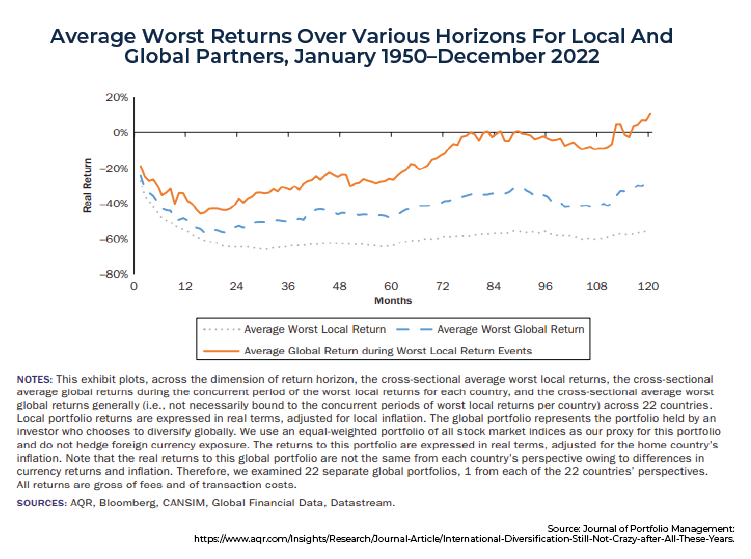

One common argument made by investors who refrain from global diversification is that, during systemic financial crises, everything does poorly, leading them to question the protection that international diversification offers during large market declines. While research may support this argument – that worst-case real returns for individual countries do tend to correspond with severe declines across all countries globally – the trend generally holds true only for the short term and the similarities in market behavior for countries around the globe tend to deteriorate over the long-term, as different countries naturally recover at different rates. But because no one can be sure of when and where these recoveries will happen, investors who are willing to spread the risk of slightly lower returns from globally diversified portfolios stand to yield the rewards of having an edge in the natural cycle of global markets in the aggregate.

Contrary to the view that global diversification may offer little protection from market declines, it is especially salient in cases of a worldwide recession – while the average individual country’s returns after such an event tend to stay depressed, global portfolios go on to eventually recover. In other words, while global diversification may not necessarily provide protection from the initial crash, it does create the potential for a significantly faster recovery. And this behavior tends to be more pronounced with longer time horizons – which are ultimately more relevant for investors with long-term wealth goals.

In addition to overlooking global long-term recovery patterns, investors often fail to consider the important role that valuation changes play in investment returns. Despite the caveat that “past performance is no guarantee of future results”, the patterns of historic past earnings data can offer insight into how a company is valued, which can influence the performance of its shareholders’ equity. For example, a strong case has been made for the predictive value of the CAPE 10, a price-to-earnings metric designed to assess relative market valuation, which is especially insightful when it comes to long-term returns. As while investment returns can be driven by underlying economic performance, such as through growth in earnings, they can also be driven by changes in valuations. And even though timing markets based on valuations in the short-term has not proven to be a successful strategy, the CAPE 10 has been positioned as a useful predictor of long-term future returns. Given the current (as of March 2023) economic positions for the U.S. CAPE (at 3.4%) and the EAFE CAPE 10 (5.6%), unless these values change, investors can reasonably estimate EAFE markets to outperform the S&P 500 by 2.2% annually.

Ultimately, the key point is that when evaluating for diversification, many investors can be prone to behavioral biases that preclude them from maintaining a well-diversified risk-appropriate portfolio that relies on a mix of U.S. and global investments. But by helping clients develop a clear understanding of the actual risks of diversification and a healthy perspective of historical market performance, advisors can prepare their clients to stay disciplined and focused on long-term results, ending out as both more informed and more insulated against inevitable market dips!

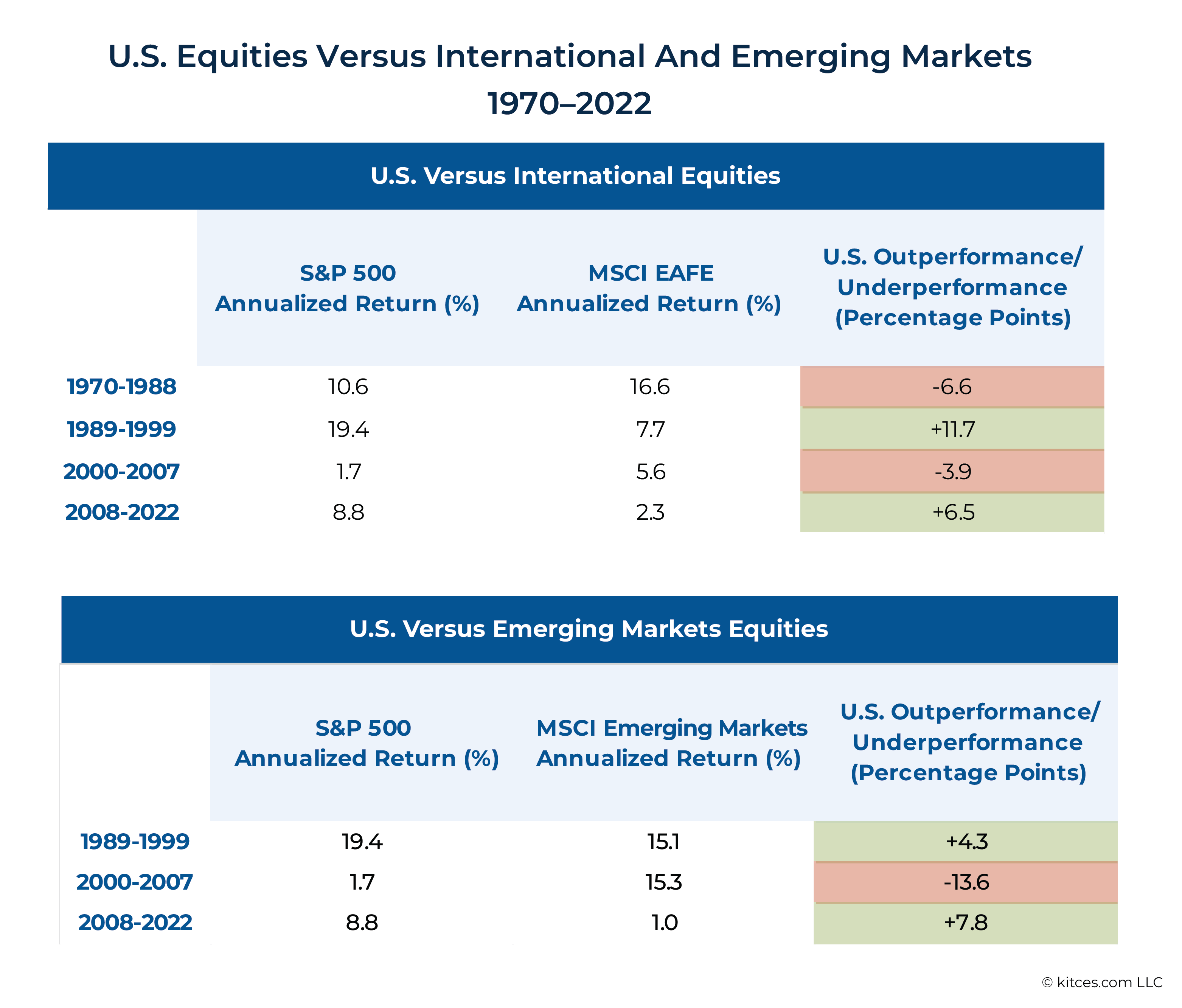

As head of financial and economic research at Buckingham Strategic Wealth, I’ve been getting lots of questions from individual investors and advisors alike about owning international equities. It’s easy to understand why: Over the past 15 years, international diversification has hurt U.S. investors compared with investing only in the U.S. market. From January 2008 through May 2023, for example, the S&P 500 Index returned 9.2%, outperforming the MSCI EAFE Index return of 2.7% by 6.5 percentage points and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index return of 1.0% by 8.2 percentage points.

For many financial advisors, the current run of outperformance for U.S. over international equities has made it increasingly challenging to communicate with clients about the wisdom of diversifying globally. And while the numbers from the last 15 years look bad enough on their own, certain behavioral biases such as recency bias (which can cause people to overweight the importance of recent events over those that occurred farther in the past) and confusing the familiar with the safe (which can lead to U.S. investors downplaying how risky U.S. equities really are) have made international diversification look even worse in the eyes of the investing public.

The underperformance of international stocks has led some to argue that the global market climate really has changed to the extent that international diversification is no longer an effective strategy to reduce country-specific risk – either because, in times of crisis, the correlations of equities around the globe now tend to rise toward 1 (or in other words, everything crashes at the same time), which means that there’s no point in diversifying; or going even further, because global equities are now highly correlated in any environment, and that with the increasing integration of global markets the world has truly become ‘flat’, eroding away any benefits that diversification once had.

Investors with a knowledge of economic theory and financial history, however, can still make a strong argument for international diversification. It’s helpful to begin with a trip down memory lane, so we can examine how the world looked to investors before the U.S. began its current stretch of outperformance.

Imagine that it’s January 1, 2008. Over the prior 8 years (2000-07), the S&P 500 Index has returned just 1.7% annually, while the MSCI EAFE Index of developed market equities has returned 5.6% (3.9 percentage points) and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index has returned 15.3%. And looking much farther back to the longest period for which there was data at that point (1970-2007), the S&P 500 has underperformed the MSCI EAFE by 0.5 percentage points per year on average (11.1% versus 11.6%) over a 38-year time horizon. In the face of the U.S. underperforming international equities over the short- and the long-term, what investor – at that point in time – would have argued against global diversification?

Looking back over the last 50+ years shows the pendulum swinging back and forth continuously between U.S. and international equities. As shown in the charts below, during the 1970s and 1980s, U.S. equities largely lagged their international and emerging market counterparts (as the U.S. economy stagnated while previously less-developed countries experienced a surge of growth and industrialization), as they also did in the early 2000s (when the end of the dotcom bubble and the aftermath of 9/11 tipped the U.S. economy into a recession). But U.S. equities outperformed both during the booming economic years of the 1990s and throughout the slow but steady recovery following the 2008 financial crisis.

*MSCI Emerging Markets Index data is only available back to its inception date of 12/31/1987

While it’s easy to see in hindsight which regions have outperformed in the past, unfortunately no one can predict in advance which one will outperform the others over any particular time period. As the above tables demonstrate, outperformance over one period tends to be followed by underperformance over the next. One of the main reasons why this occurs is that much of the outperformance of one region during a certain time period tends to be a result of rising valuations in that region relative to the others – and while rising valuations lead to higher realized returns, they also result in lower future expected returns (since that region’s valuations will likely regress back towards the mean at some point), at the same time when other regions with comparatively lower valuations can expect to achieve higher future returns, causing the pendulum to swing back again.

While these cycles of out- and underperformance are predictable at a high level, there are no crystal balls allowing us to foresee exactly when each shift will occur. The logical conclusion, then, is that investors should be diversified internationally – i.e., holding a mix of both U.S. and international asset classes rather than betting on one to outperform the other – in order to capture the swings in valuation whenever they occur. In reality, however, many investors instead tend to simply buy what has performed best in the most recent period (at higher valuations and thus lower expected returns) and sell what has underperformed (at lower valuations and thus higher expected returns) – the exact opposite of the Investing 101 motto of ‘buy low, sell high’. For investors, weighing recent results over historical evidence would have resulted in overweighting international stocks in 1990, U.S. stocks in 2000, international stocks again in 2008 (all at the wrong time, when each asset class was about to enter a period of underperformance)… and once again, U.S. stocks today.

Beyond the faulty logic of buying after outperformance and selling after underperformance, investing only in a single country or region goes against the basic economic principle that diversification is the only ‘free lunch’ in investing – in other words, that a globally diversified portfolio can be expected to produce better risk-adjusted returns than any one country. Yet many investors behave as if the opposite is true, specifically as pertains to their home country: Investors in developed markets (including in the U.S.) often believe that their own country not only has higher expected returns than other countries, but is also a safer place to invest.

This home-country bias goes against the most basic investment principle that risk and expected return in a non-diversified portfolio are positively correlated (that is, assets with higher expected long-term returns will also have higher expected short-term volatility). Thus, if you believe the U.S. is a safer place to invest, logically you should expect that U.S. returns will be lower, not higher, than the returns of riskier international stocks. Instead, investors who want to reduce risk without correspondingly lowering the expected return can do so by adding less-correlated assets with the same expected return (e.g., by adding additional countries to a single-country portfolio).

The Case For International Diversification

Cliff Asness, Antti Ilmanen, and Dan Villalon examined the arguments for and against international diversification in their paper “International Diversification—Still Not Crazy after All These Years”, published in the April 2023 issue of The Journal of Portfolio Management. In terms of economic theory, they note the following:

Diversification is one of the most fundamental and important ideas in modern finance. It’s also a practical result of how markets work.

This is because the only “market-clearing” or “macro-consistent” portfolio is one that’s market-cap weighted—one investor’s overweight is another investor’s underweight [author’s note: not everyone can overweight U.S. stocks]. So, if anyone decides they’re best off holding mostly their own country’s equity market, then it means other investors in other countries must also be more home biased. The trouble with this proposition is that it’s simply not logical for investors in every country to believe their home market is going to outperform. It may be patriotic, but it sure isn’t rational.

Everything Crashes At The Same Time, So Why Bother?

The bear markets of 1973–1974 (when the S&P 500 lost 37.2% and the MSCI EAFE lost 33.2%), 2000–2002 (when the S&P 500 lost 37.6% and the MSCI EAFE lost 42.8%), and 2008 (when the S&P 500 lost 37.0% and the MSCI EAFE lost 43.0%) demonstrated that during systemic financial crises, markets tend to crash together. Because the point of diversification, as noted previously, is to add assets to the portfolio that don’t all move together at the same time, it’s reasonable to wonder whether international diversification really provides any protection when large market declines seem to affect all markets simultaneously.

Addressing this question, Asness et al. concede the point that diversification won’t necessarily add protection to a portfolio during any one market crisis: As the authors put it, “worst cases for individual countries are similar to worst cases for globally diversified portfolios.” But while global diversification may not do much to reduce risk in the short term, they go on to add, “there’s an even bigger risk for investors: long-term pain. Extended bear markets are more likely to prevent investors from meeting their long-term wealth goals than short crashes.” To better evaluate the true value of diversification, then, consideration must be given to how it performs over longer horizons, as long-drawn-out bear markets can be significantly more damaging to wealth than short-term volatility (particularly for investors in the distribution stage of their investing lifecycle).

The following chart from their paper shows how a globally diversified portfolio has historically provided downside protection. It shows how the ‘worst-case’ real return for an individual country (represented by the grey dotted line) tends to initially correspond with a severe decline across all countries (represented by the orange line) – but while the average individual country’s returns after such an event tend to stay depressed, the global portfolio goes on to eventually recover. In other words, while global diversification doesn’t necessarily provide protection from the initial crash, it does create the potential for a significantly faster recovery.

Historical evidence further supports the idea that while international diversification doesn’t necessarily work in the short term, with markets moving (mostly down) in tandem during systemic crises, it does often prove to work in the long run. In a 2011 paper published in Financial Analysts Journal, “International Diversification Works (Eventually)”, Asness, along with co-authors Roni Israelov and John M. Liew, found that over the long run, markets don’t exhibit the same tendency to suffer or crash together as they do during short spikes of volatility (when selling is largely driven by fear and panic); rather, they diverge over time based on actual economic factors, meaning that investing in any single country means betting on that country’s economic performance over the long run. To put it another way, global diversification protects not against the risk of a single worldwide meltdown, but instead against the risk of any single country’s stocks underperforming the global market over a period of decades.

In the 2023 Journal of Portfolio Management paper, Asness et al. update the data from the previous paper through 2022 and conclude that “international diversification does a pretty great job of protecting investors over the long term”. Their findings are consistent with those of Mehmet Umutlu and Seher Gören Yargi, authors of the May 2021 study, “To Diversify or Not to Diversify Internationally?”, who concluded that international diversification is still important and has the potential to reduce portfolio risk because of how “correlations jump during recessions with a tendency to revert in stable periods”, even in more recent years when increasing globalization might lead one to expect correlations to be higher in all economic environments.

For a specific example of the long-term benefits of diversification, look to Japan. At the dawn of the 1990s, Japan was coming off of a decade in which it had outperformed both U.S. and global equities as a whole. Focusing just on recent performance would have led investors to believe that Japan would continue to be a good bet going forward, but what has actually happened since then has been a completely different story: From January 1990 through May 2023, the MSCI Japan Index returned just 0.9% per year.

The poor returns Japan has experienced over the last 30+ years weren’t a result of systemic global risks. They happened because of Japan’s idiosyncratic problems during that time period, such as a high and rising debt-to-GDP ratio and an aging population (both of which the U.S. economy may be facing in the years ahead). An investor in 1990, however, would have had no way of predicting the economic factors that would drive Japan’s long-term underperformance (or those of any other country, for that matter); in the same way, today’s investors have no way of knowing how economic performance will shake out in the decades ahead, nor which countries – the U.S. or otherwise – will take the lead. And just as Japanese investors would have benefited from diversifying away from their home country, U.S. investors today face the risk that investing in their own country based on recent history will lead to a long-term underperformance of the global market.

Changes In Valuations Can Lead Investors To Make The Wrong Conclusions

When forming expectations about future returns, investors’ biases towards recent and/or desired outcomes can lead them to fail to consider how past returns were earned. As we saw in the previous section, investment returns can be driven by underlying economic performance – such as through growth in earnings – or by changes in valuations (price-to-earnings multiples), and it makes a big difference for projecting future returns if the past returns were earned through growth in earnings or changes in valuations. In other words, just as trees don’t grow up and up to the sky forever, neither do price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios.

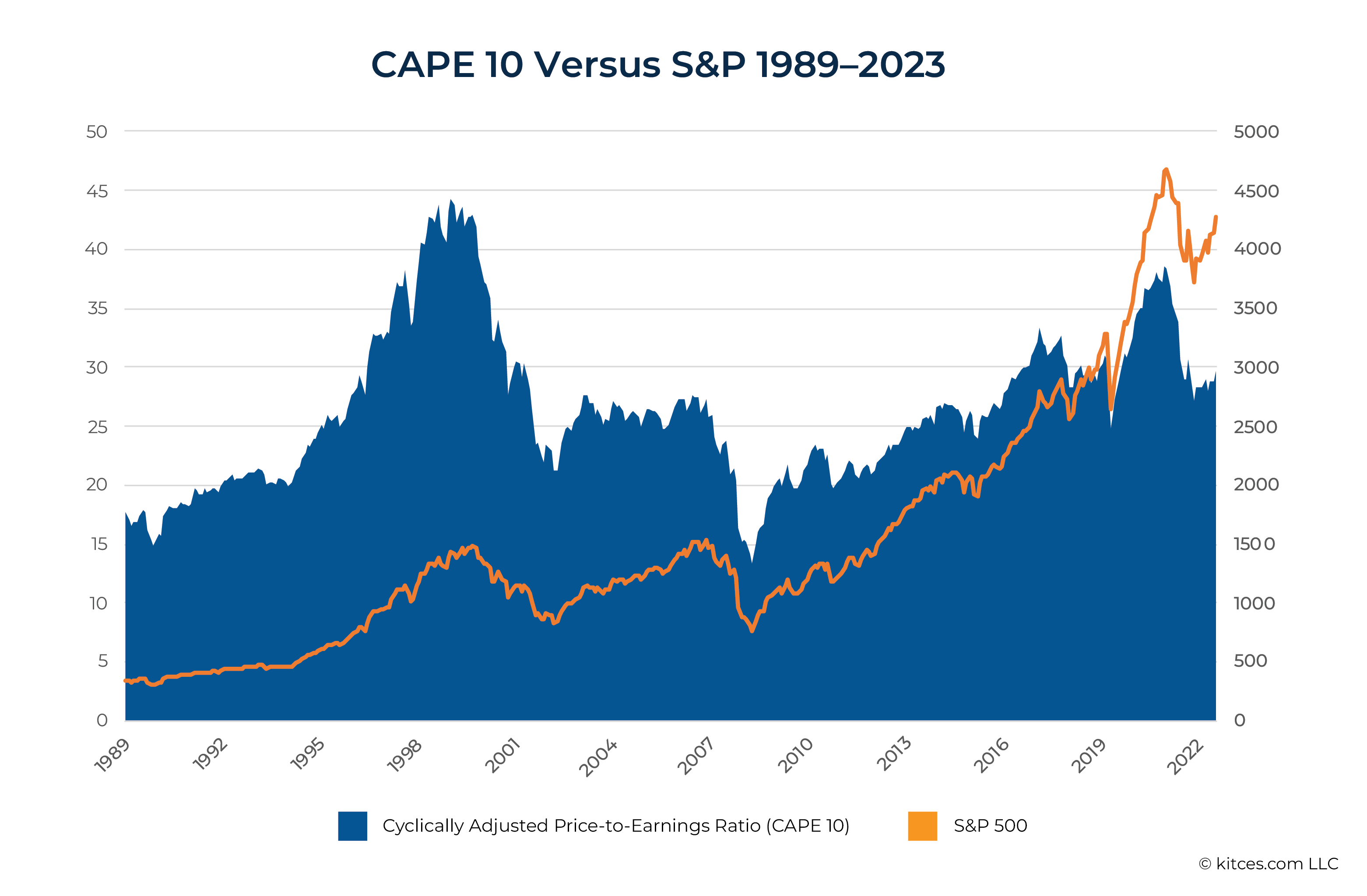

Consider the following pattern for the Shiller Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings Ratio, or CAPE 10. (Note that its inverse Earnings-to-Price ratio or ‘earnings yield’ is as good a predictor as we have of future real returns). The data goes back to 1871, with the historical CAPE 10 mean being 17.0, or an earnings yield of 5.9%.

- At the end of 1989 the CAPE 10 stood at 17.7.

- By the end of 1999, it had risen to 44.2, explaining much of the superior performance of the S&P 500 over that period. Of course, rising valuations predict lower future returns.

- By the end of 2002 the CAPE 10 had fallen to just 23, explaining much of the poor performance of the S&P 500 from 2000 through 2002.

- By October 2007 (just prior to the Global Financial Crisis) the CAPE 10 had risen to 27.3

- By March 2009, the CAPE 10 had fallen all the way to 13.3.

- By the end of 2021, the CAPE 10 had almost tripled, rising to 38.3, explaining the strong performance of the S&P 500 over that period.

- The bear market of 2022 saw the CAPE 10 fall to 28.3.

- As of June 9, 2023 the CAPE 10 had risen back to 30.1, helping to explain the strong performance year-to-date of the S&P 500.

As is clear from the chart below comparing the CAPE 10 from 1989 to the present with the S&P 500 index price over the same time period, the bull markets of the late 1990s, 2003–2007, and 2009–2021 occurred as companies became higher-priced relative to their earnings, while the bear markets of 2000–2002, 2008, and 2022 were marked by steep reversions of those valuations towards the mean level.

Additionally, the chart above shows a clear pattern where high valuations forecast lower future returns and low valuations forecast higher returns (though unfortunately, while the CAPE 10 is as good of a predictor of long-term future returns as we have, timing markets based on its valuations in the short-term has not proven to be a successful strategy).

What does this have to do with international diversification? As Asness, Ilmanen, and Villalon showed in their paper, since 1990 the vast majority of the outperformance of U.S. equities versus the MSCI EAFE Index was due to changes in valuations: “In 1990, US equity valuations (using Shiller CAPE) were about half that of EAFE; at the end of 2022, they were 1.5 times EAFE.” And although the U.S. outperformed international equities by 4.6 percentage points per year from 1990 to 2022, Asness et al. conclude that if valuations had remained unchanged over that time, the U.S. outperformance would have been just 1.2 percentage points per year. Understanding that U.S. valuations had risen over 3 times as much as their peers over the last 30 years, driving most of the outperformance of U.S. stocks over that time, the U.S. seems to be a much likelier candidate for a reversion going forward, which would lead to underperformance for investors with a U.S. bias.

It’s worth noting that there have certainly been logical reasons for U.S. outperformance in recent years. As Asness et al. noted: “The positive story is that the US is rich for a reason – it is indeed hard to love European or Japanese equities except for valuation reasons.” However, valuations matter – as shown above, they are our best predictor of future returns. The rising relative valuation of U.S. equities over EAFE equities to historically rich levels means that, without even considering a potential mean reversion in relative valuations, international equities now offer significantly higher expected returns. As of the end of March 2023, while the U.S. CAPE 10 earnings yield (the inverse of the CAPE 10) stood at 3.4%, the EAFE CAPE 10 earnings yield stood at 5.6%. Thus, if valuations do not change, investors should expect EAFE to outperform the S&P 500 by 2.2% per annum. If valuations reverted toward their historical means, the outperformance gap would be even wider.

International Diversification Is Especially Effective For Factor-Based Investors

Asness, Ilmanen, and Villalon note the following in their 2023 research paper:

Country equity markets have offered some degree of diversification even over the short run (0.75 median correlation across markets), and we’ve already argued how valuable that diversification can be, particularly over the long run. But correlations among long–short factors (e.g., the stock selection value factor in one country compared with the same implementation of value in another country) are substantially lower—0.26 median correlation across countries for the value factor up to 0.42 for the cross-country momentum factor.

They go on to add:

In addition to how diversifying these factors are across countries, they also tend to be fairly lowly correlated to equity markets themselves—that is, not only do these factors tend to be strongly diversifying to each other, they also tend to be strongly diversifying to the main risk in most investor portfolios and to macro risks.

They make the case that the low cross-country correlations of factors provide diversification benefits reducing the tail risk to investors, as do the low to negative correlations of the size, value, momentum and profitability/quality factors not only with the market, but with each other.

Advisor Takeaways

While economic theory and the empirical evidence suggest that the most prudent strategy is to diversify globally, it must be acknowledged that for many investors, diversification can be hard. The reason for this is that even a well-thought-out, diversified portfolio will inevitably go through periods of poor performance. And sadly, when it comes to judging performance, it is my experience that most investors believe that 3 years is a long time, 5 years is a very long time, and 10 years is an eternity.

Yet, as financial economists know, and the evidence in research papers such as Asness et al. bears out, events that take place over 10 years are very likely to be nothing more than noise that should be ignored. Otherwise, instead of following a disciplined rebalancing strategy of buying low (i.e., the recent underperformers) and selling high (the recent outperformers), investors chasing recent trends tend to do the opposite, buying high and selling low. Smart investors know that if they are well diversified, they will almost always have positions that have underperformed. To obtain the benefits of diversification you have to be willing to accept that reality and have the discipline to stay the course.

Thus, it is critical for advisors to educate investors about the logic and benefits of global diversification and also explain the “risks of diversification”, what is called “tracking error” risk. Being forewarned about such risk, the investor will be better prepared to stay disciplined. Remember, investors cannot run away from risks, they only get to choose which risks they take. Failing to diversify globally creates the risk that the U.S. might follow in Japan’s footsteps and be the next country to underperform for the next 30 years. Putting all your eggs in one basket is not a prudent strategy, no matter how familiar you are with, or how closely you watch, that basket.

The evidence has demonstrated that although the benefits of a global equity allocation may have been reduced by market integration, they have not disappeared. While global diversification can disappoint over the short term (as has been the case for those who have diversified away from U.S. stocks in the last 15 years), over longer time periods it is still the free lunch that economic theory and common sense imply.

Before making the mistake of confusing the familiar with the safe, no one knows which country or countries will experience a prolonged period of underperformance. That uncertainty is what international diversification protects against and is why broad global diversification is still the prudent strategy.

A good starting point for deciding how much to allocate to international markets is global market capitalization, i.e., investing in each country or region in proportion to its weight within global capital markets. This can be easily accomplished by owning 2 total market funds such as Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX) and their Total International Stock Index Fund (VTIAX). And as Asness and his co-authors pointed out, adding exposure to other factors (such as size, value, momentum, and profitability/quality) provides further diversification benefits.

That said, however, there are some valid reasons for a U.S. investor to have a small home country bias. Namely, the implementation costs of investing internationally can be higher in terms of expense ratios of funds, trading costs, and taxes, which can offset some of the benefits of diversification. On the other hand, if one is still employed, labor capital is likely to be more exposed to the idiosyncratic risks of the U.S. economy. Thus, if labor capital is highly correlated to the U.S. economy, an even higher allocation to international stocks might be considered.

The bottom line is that while the prudent strategy is to globally diversify, unless the mistake of resulting (judging the quality of a decision by the outcome instead of the decision-making process) can be avoided, investors will likely fall prey to recency bias and abandon even a well-thought-out plan, likely at the wrong time. Helping to keep investors disciplined is one of the most important roles of a financial advisor.

Larry Swedroe is head of financial and economic research for Buckingham Wealth Partners. For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency have approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed adequacy of this article. Information may be based on third-party data which may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Third-party information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. Mentions of specific securities are for informational purposes only and there are options available to achieve the objectives mentioned above. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio nor do indices represent results of actual trading. Information from sources deemed reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Performance is historical and does not guarantee future results. All investments involve risk, including loss of principal. LSR-23-498