Executive Summary

Last year, the Biden Administration announced a sweeping package of student loan relief programs intended to ease the pressure on borrowers affected by the skyrocketing student debt of recent years. The two key pillars of the administration's package were a proposed one-time cancellation of up to $10,000 of Federal student debt per borrower, and a new Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan featuring much more borrower-friendly terms than previously existing IDR plans. Fast forward to this summer, and the U.S. Supreme Court has struck down the loan forgiveness portion of the administration's plan. However, the new IDR plan (named the Saving on A Valuable Education, or SAVE Plan) is still moving forward, and in response to the Supreme Court's decision, the Biden administration has released its final regulations regarding the new repayment plan.

In this post, Kitces Senior Financial Planning Nerd Ben Henry-Moreland explains the new SAVE Plan's features, how it changes the student loan planning landscape for new and existing borrowers, and what financial advisors can do to help clients with student loans prepare in light of the upcoming end of the current student loan payment pause – which has been in effect since March of 2020 – on August 31, 2023.

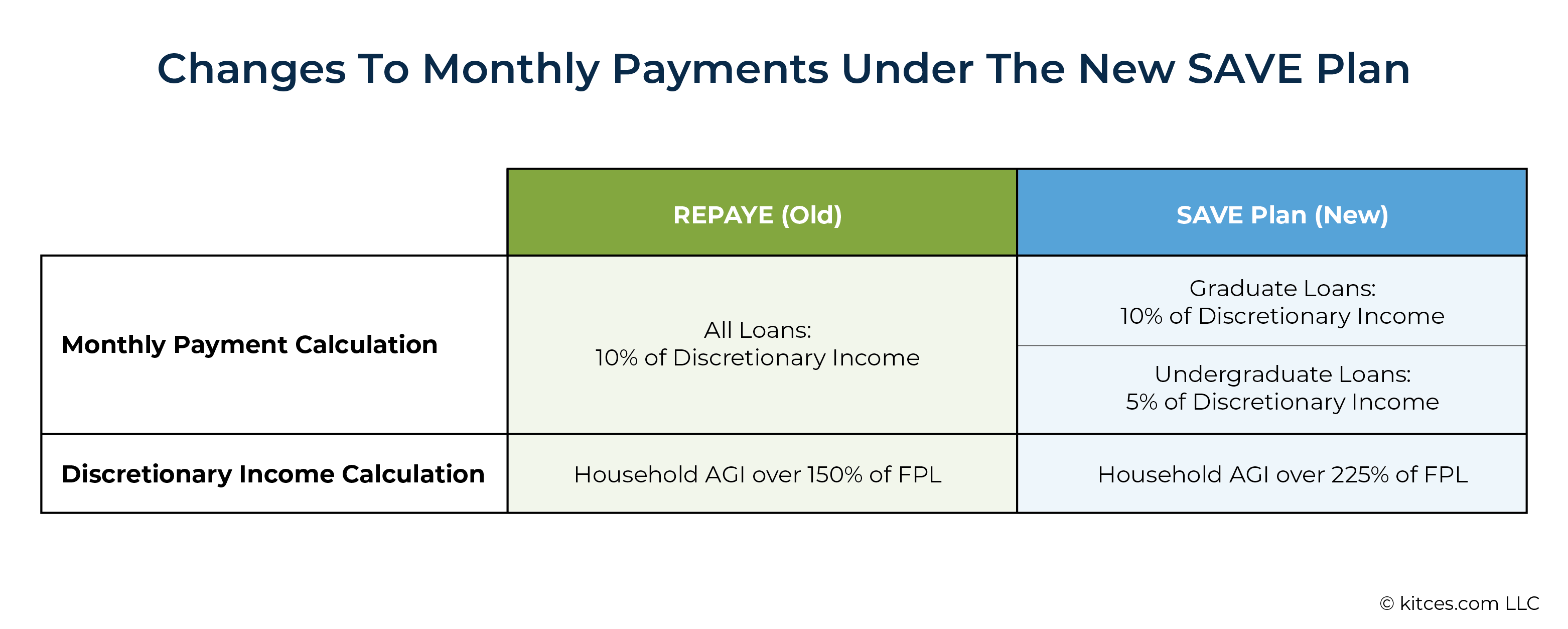

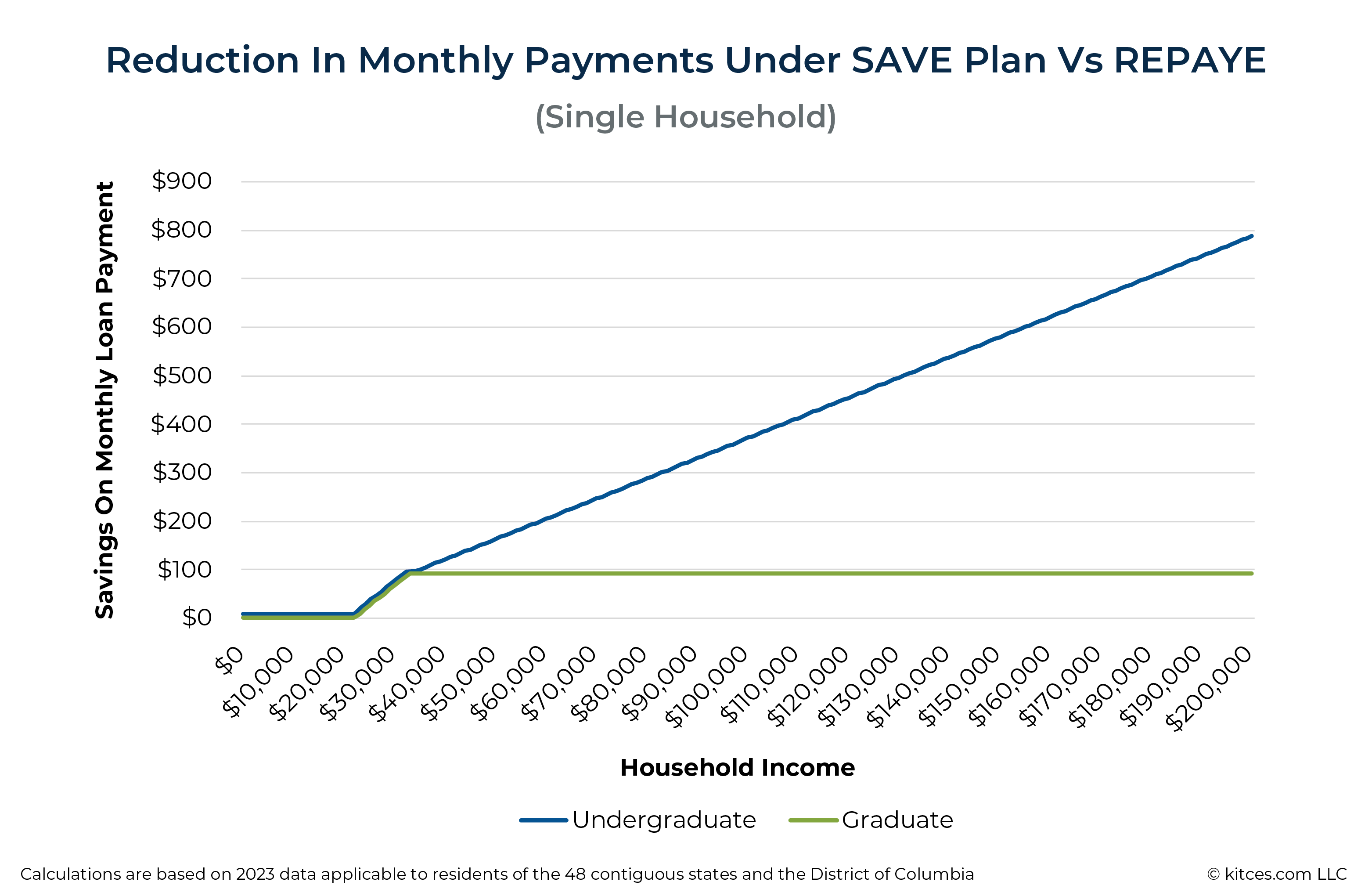

The main feature of the new SAVE Plan (which will replace the existing REPAYE plan in the IDR plan lineup) is that it will reduce the monthly student loan payments for many borrowers by decreasing the required payment for loans taken out for undergraduate education from 10% of a borrower's discretionary income (for those on IBR, PAYE, or REPAYE repayment plans) to 5%, while also adjusting the calculation for discretionary income to lower it for most borrowers. As a result, undergraduate loan borrowers will see their payments slashed by more than half of what they would have been under other plans, while graduate loan borrowers will also have a smaller but still significant reduction in their payments.

Additionally, the SAVE Plan fixes several issues that existed in other repayment plan options by allowing married couples who file as Married Filing Separately to exclude their spouse's income from their monthly loan payment calculation (which can significantly reduce the payment amount for borrowers whose spouses earn higher incomes) and fully subsidizing any loan interest that isn't covered by a borrower's monthly payment (ensuring that loans won't negatively amortize for borrowers on the SAVE Plan).

Borrowers on the SAVE Plan will also have expanded options for loan forgiveness under the new rules, where those whose loans originally totaled no more than $12,000 will now be eligible for forgiveness after 10 years of monthly payments (compared to 20–25 years under other IDR options). Additionally, they will be able to get credit for forgiveness during months where they didn't make payments due to a range of deferment or forbearance periods, as well as for payments made on loans that were consolidated (which previously reset the clock on forgiveness and required the borrower to make another 20 –25 years of payments to be eligible for forgiveness).

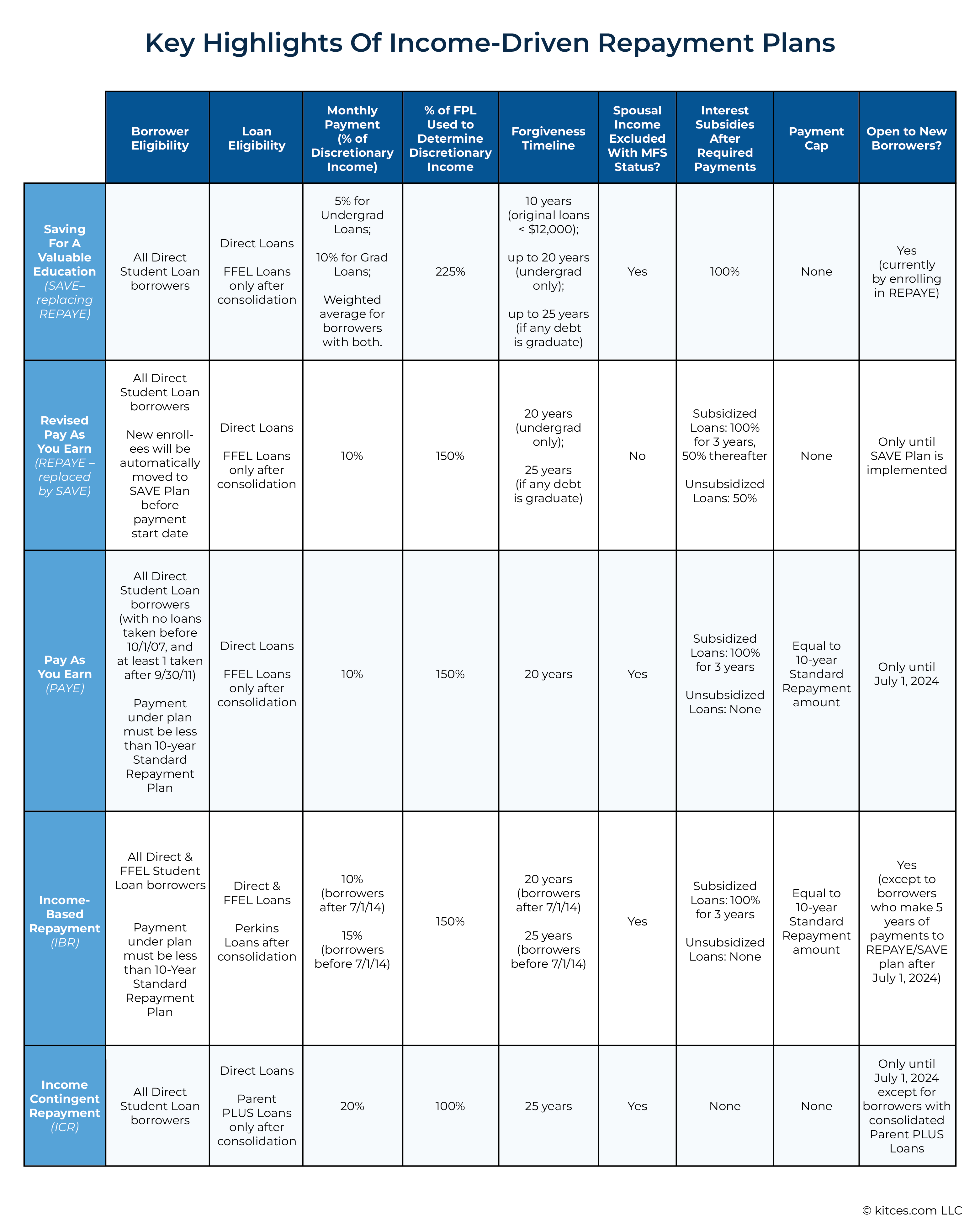

One other effect of the SAVE Plan and other new repayment plan regulations announced by the Department of Education will be to reduce the number of IDR plans that a borrower can choose from since, after the new rules' implementation on July 1, 2024, several of the other plans will be either limited or closed off entirely to new enrollees. However, there are still plenty of planning opportunities around student loans – including which of the remaining IDR options to choose from, when to recertify income, and whether to file as Married Filing Separately in order to exclude spousal income.

Ultimately, with student loan planning being effectively a new part of many clients' financial planning situations (since the 3 1/2-year pause in required payments made it easy to forget what life with student loan payments was like), now is an opportunity for advisors to help clients re-navigate the thicket of potential IDR options and provide some clarity on a path forward. Because while it was always certain that payments would resume again someday, it was never certain until now just when and how that would take shape – but with the resumption of payments coming in October, now is the time to make sure the transition goes as smoothly as possible!

In August of 2022, the Biden administration unveiled a wide-ranging package of student loan reform programs as (what was supposed to be) a long-awaited fulfillment of a campaign promise to bring relief to student loan borrowers.

The headline piece of the package was the cancellation of up to $10,000 (and in some cases, up to $20,000) of student loan debt for individuals within certain income thresholds, but that provision was nearly immediately challenged in court by opponents of broad-stroke student loan forgiveness. In November 2022, a Texas district court judge blocked the student loan forgiveness plan from taking effect, and it remained in legal limbo for several more months until June 30, 2023, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued a final ruling rejecting the forgiveness plan.

For now, then, it appears that the prospect of forgiveness of thousands of dollars of student loan debt in one stroke is dead. But while loan forgiveness got the most headlines – and would have certainly been impactful for millions of people struggling with student loan debt – it wasn't the only part of the Biden administration's student debt relief package.

Most notably, the other key piece of the relief package was a proposed new Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan, which would, among other things, lower the monthly student loan payments of eligible borrowers, allow some loans with an original balance of under $12,000 to be forgiven after 10 years instead of the usual 20, and subsidize unpaid interest in order to prevent negative amortization (i.e., growth via accrued interest) of loan balances (discussed in more detail later). And unlike the one-time forgiveness plan, the new IDR plan was not affected by the Supreme Court's decision, still standing to go into effect over the next year.

The original debt relief plan from last August contained enough details about the new IDR plan to make it clear that it would be attractive for many borrowers but left open many questions about (among other things) who would be eligible for the new plan along with details about how it would be implemented. Proposed regulations released in January 2023 filled in more of the gaps, but it wasn't until June 30 – immediately after the Supreme Court struck down the debt forgiveness plan – that the U.S. Department of Education released its final regulations for the new IDR plan, newly christened the Saving on A Valuable Education (SAVE) Plan.

With Federal student loan payments set to resume after August 31 (or more specifically, with interest accruing starting in September and the first monthly payments due in October), financial advisors who have clients with student loan debt will likely be fielding many questions in the months ahead as borrowers prepare to fit student loans back into their financial picture after what for many of them will have been more than 3 ½ years – a full 44 months (from February 2020 to October 2023) – in between payments. Because although the immediate forgiveness of $10,000 to $20,000 of student loan debt may be off of the table for the time being, proper planning around a borrower's remaining student loan repayments (including knowing the ins and outs of the new SAVE Plan) has the potential to save at least that much in the long term.

The New SAVE Plan Modifies And Replaces The Existing REPAYE Income-Driven Repayment Plan

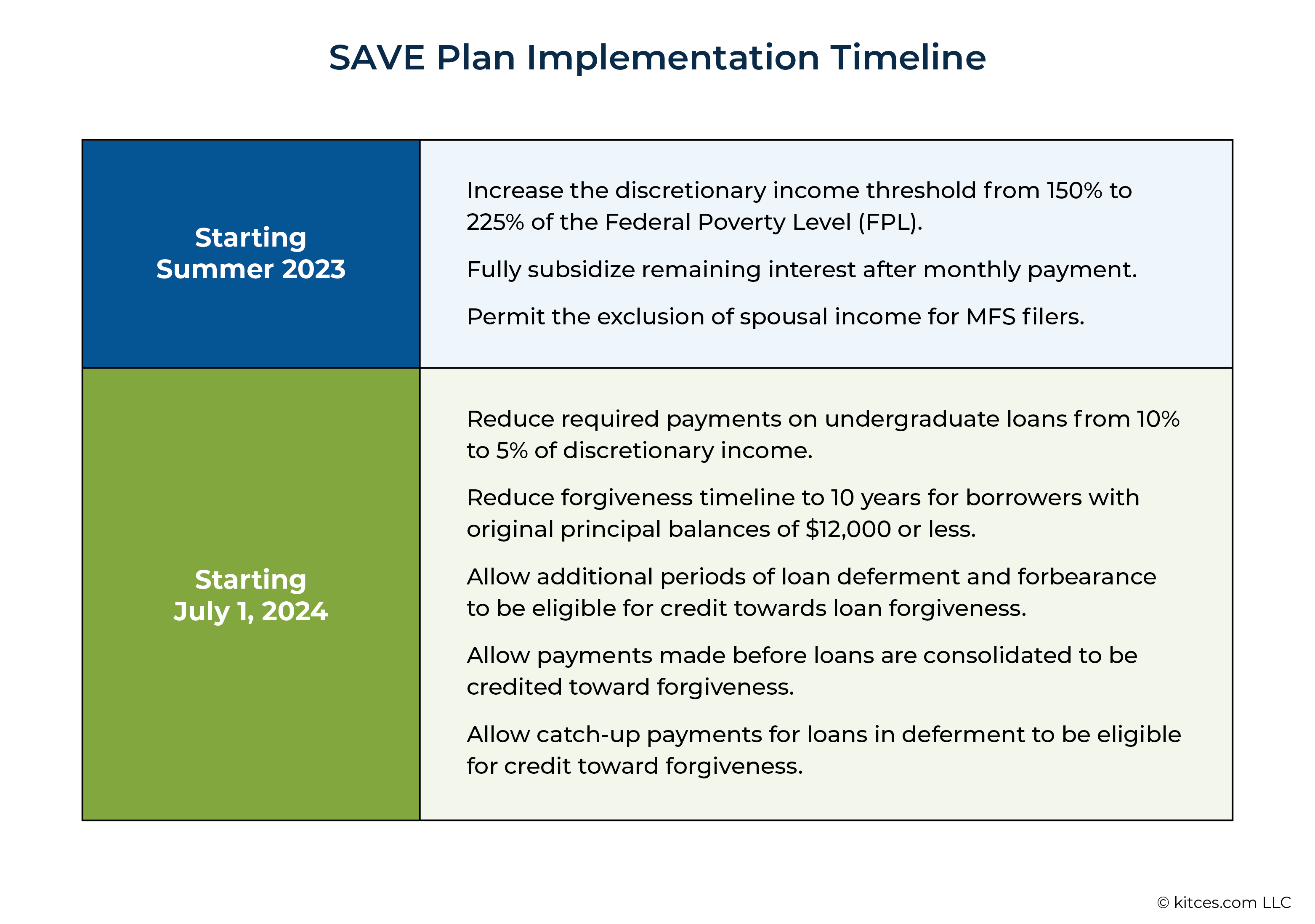

Although the SAVE Plan was originally announced as a "new" Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan – meaning it would have slotted in alongside the existing IDR plan options of Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR), Income-Based Repayment (IBR), Pay As You Earn (PAYE), and Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE) – the Department of Education has announced that the new plan will actually be replacing the existing REPAYE plan. Anyone currently enrolled in the REPAYE plan will automatically be moved into the SAVE Plan before payments resume in October, and anyone who applies to sign up for the REPAYE plan before the SAVE Plan is live will also be moved over automatically later this summer. Additionally, as part of the new regulations, the PAYE option will be closed off to new enrollees, while the ICR and IBR options will be restricted only to certain borrowers (more on this later).

In practice, however, the new SAVE Plan is really more of a modification of the existing REPAYE Plan, keeping some of its elements intact while revising others. What's significant about this is that it means that all borrowers with Federal Direct student loans are eligible for the SAVE Plan: While some other IDR plan options have restrictions on who can enroll based on the date of the loan (like the Pay As You Earn [PAYE] Plan that's only open to borrowers who took out loans after 10/1/2007, and the newer, more generous version of the Income-Based Repayment [IBR] that's only available for loans after 7/1/2014), the SAVE Plan, like the REPAYE plan before it, is open to all borrowers for all types of Federal student loans (except Parent PLUS loans) regardless of the date the loans were taken out.

Somewhat confusingly, the Department of Education even refers to the SAVE and REPAYE Plans interchangeably in their final regulations, and notes in their fact sheet on the change that borrowers might see both names used; for the purposes of this article, however, "SAVE Plan" will generally refer to the new plan and "REPAYE" will refer only to the 'old' REPAYE Plan.

Reduced Monthly Payments Under The SAVE Plan

The most straightforward change that comes along with the new SAVE Plan is a reduction in the monthly payment amount for borrowers on the plan. Like REPAYE (as well as the other IDR plans), monthly payments under the SAVE Plan are calculated as a percentage of the borrower's "discretionary income", defined as the household Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) above a threshold calculated as a multiple of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) for that household size, divided into 12 equal monthly installments.

Under the existing REPAYE plan, the annual payment was calculated as 10% of discretionary income, which was defined as household AGI above 150% of the FPL. With the new SAVE Plan, borrowers will pay only 5% of their discretionary income on loans used to pay for undergraduate education (with the percentage remaining at 10% for graduate school loans), while the threshold used to define discretionary income has been increased from 150% to 225% of the FPL.

With a higher income threshold that effectively lowers discretionary income for most borrowers and (at least for undergraduate loans) a lower percentage of discretionary income used to calculate monthly payments, the new SAVE Plan will result in lower monthly payments for pretty much everyone compared to the previous REPAYE Plan (except for those whose monthly payments were already $0 under REPAYE, i.e., their income was under 150% of the FPL).

Nerd Note:

The Federal Poverty Guidelines set the Federal Poverty Levels annually. Alaska and Hawai'i both have their own individual FPL numbers, while the other 48 states and the District of Columbia use the same number throughout. Therefore, loan borrowers in Alaska and Hawai'i will have slightly different discretionary incomes (and therefore different monthly loan payments) than borrowers in other states with the same income and household sizes.

Example 1: Max is a single tax filer living in Arizona whose AGI last year was $150,000. He is on the REPAYE Plan for his Federal undergraduate loans, which means he'll have automatically switched over to the SAVE Plan by the time his payments resume in October 2023.

Because Max lives in Arizona by himself, his discretionary income will be determined based on the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) for the 48 contiguous states for a 1-person household ($14,580 for 2023). Under the new SAVE Plan, Max's discretionary income is calculated as his AGI minus 225% of the FPL, and his monthly payments will be based on 5% of his discretionary income (since he has undergraduate student loans only).

Thus, his monthly payments under the SAVE Plan are calculated as follows:

Discretionary Income (SAVE Plan): $150,000 – (225% × $14,580) = $117,195

Monthly Payment (SAVE Plan): (5% × $117,195) ÷ 12 = $488.31

If Max were to remain under REPAYE (e.g., had the SAVE Plan not been created), his monthly loan payment would have been determined as follows:

Discretionary Income (REPAYE): $150,000 – (150% × $14,580) = $128,130

Monthly Payment (REPAYE): (10% × $128,130) ÷ 12 = $1,067.75

Which means that with the SAVE Plan, Max's monthly student loans will be reduced by $1,067.75 − $488.31 = $579.44 – more than half his payment amount under his original REPAYE plan!

For borrowers with only undergraduate loans, the SAVE Plan will reduce monthly payments to 5% of discretionary income – less than half of what they would have been under REPAYE. For those with graduate loans, the reduction won't be nearly as dramatic since they'll pay the same 10% of their discretionary income as they would have under REPAYE; however, because the FPL threshold used to determine discretionary income is 50% higher (225% under the SAVE Plan versus 150% for REPAYE) – meaning that borrowers will have less 'discretionary' income calculated under SAVE than they would have under REPAYE – graduate loan borrowers will see at least a modest decrease in their monthly payment under the new plan.

Borrowers on the SAVE Plan with both undergraduate and graduate loans (or with Federal consolidation loans combining both undergraduate and graduate debt) will have their loan payment calculated using a weighted average based on the loans' original balances, using 5% of the borrower's discretionary income for undergraduate loans and 10% of discretionary income for graduate loans.

Example 2: Josie took out $60,000 in Federal student loans to help pay for her undergraduate degree. 5 years later, she went to law school and took out an additional $40,000 in Federal student loans. After another 5 years, she consolidated the 2 loans into a single Federal Direct consolidation loan and enrolled in the REPAYE Plan.

When Josie switches to the SAVE Plan, the percentage of her discretionary income that will be used to determine her monthly payments will be based on the weighted average of 5% of the original undergraduate loan balance ($60,000) and 10% of the original graduate loan balance ($40,000).

Which means that her monthly payments will be (5% × ($60,000 ÷ $100,000)) + (10% × ($40,000 ÷ $100,000)) = 7% of her annual discretionary income, divided into 12 payments.

Married-Filing-Separate Borrowers Can Exclude Spouses' Incomes

When the new Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan was first announced last August, one of the biggest questions left unanswered was whether married borrowers filing their taxes as Married Filing Separately (MFS) could exclude their spouse's income when calculating their monthly student loan payment. One of the major drawbacks of the existing REPAYE Plan was that borrowers were required to include their spouse's income in their monthly payment calculation regardless of whether they filed separately or jointly. This meant borrowers with higher-earning spouses were required to pay significantly more in student loan payments than they would pay as a single filer.

As the Department of Education's final regulations confirm, the new SAVE Plan does allow MFS filers to exclude their spouse's income when calculating their monthly loan payments. Although MFS status does come with some drawbacks and usually results in paying higher overall taxes than Married Filing Jointly (MFJ) status, in the right circumstances, the amount saved on student loan payments can easily make the tradeoff worthwhile.

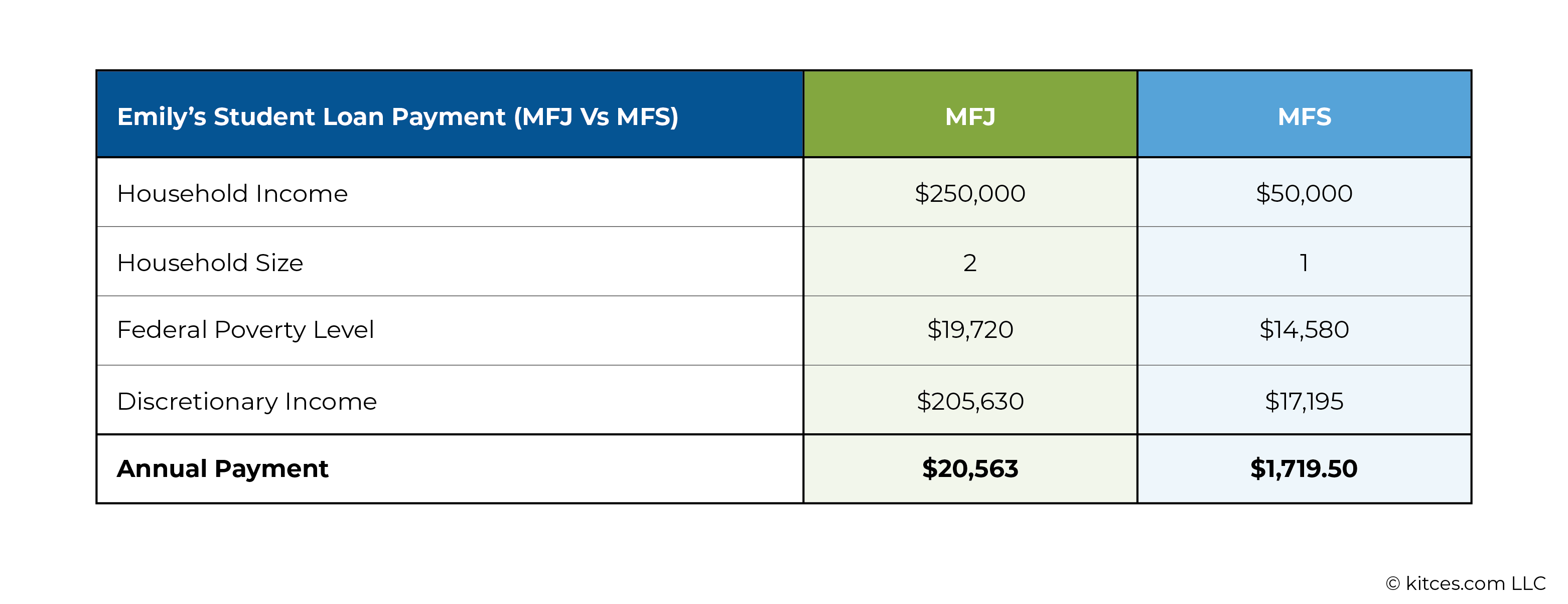

Example 3: Emily and Amy are a married couple who live in New Hampshire. Emily works at a nonprofit and earns $50,000 per year, while Amy is a consultant earning $200,000.

Emily has $80,000 in outstanding student loans from graduate school and is currently enrolled in the REPAYE plan. She will be moved to the new SAVE Plan once her payments restart this year.

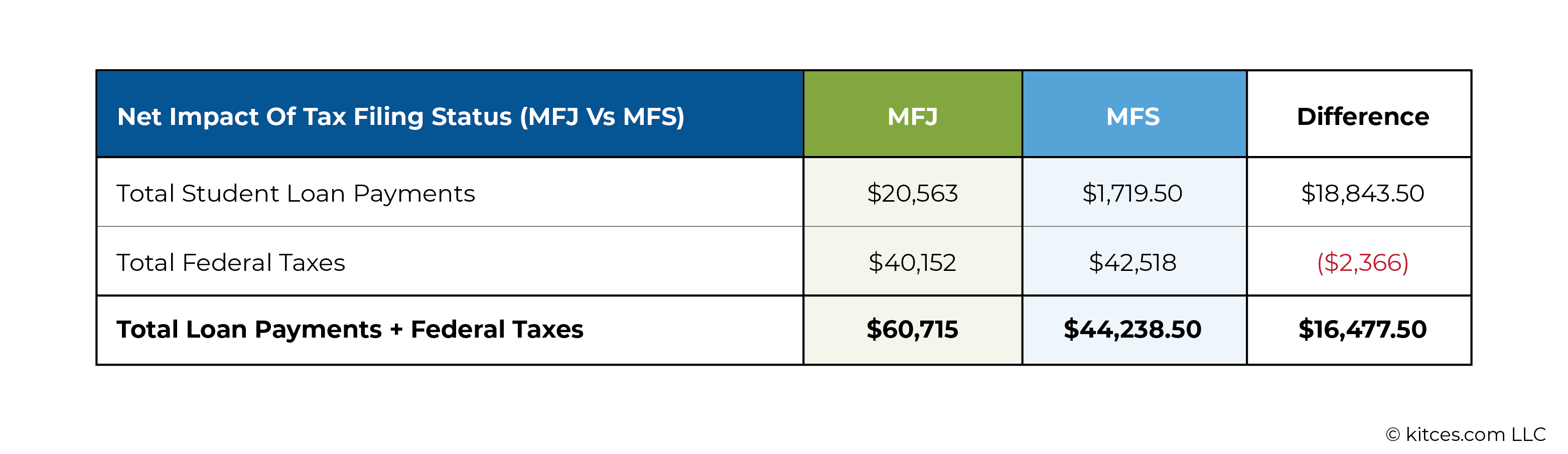

If Emily and Amy file their taxes jointly for 2023, then, for the purposes of calculating Emily's student loan payments in 2024, they would have a household size of 2 and a household income of $250,000. The 2023 Federal Poverty Level (FPL) for a 2-person household in New Hampshire is $19,720, so Emily's discretionary income would be $250,000 – (225% × $19,720) = $205,630, and her total student loan payments for 2024 would be 10% × $205,630 = $20,563.

On the other hand, if they were to file MFS for 2023, then Emily would have a household size of 1 with an income of $50,000. The FPL for a 1-person household is $14,580, so Emily's total student loan payments with MFS status would be 10% × ($50,000 – (225% × $14,580)) = $1,719.50.

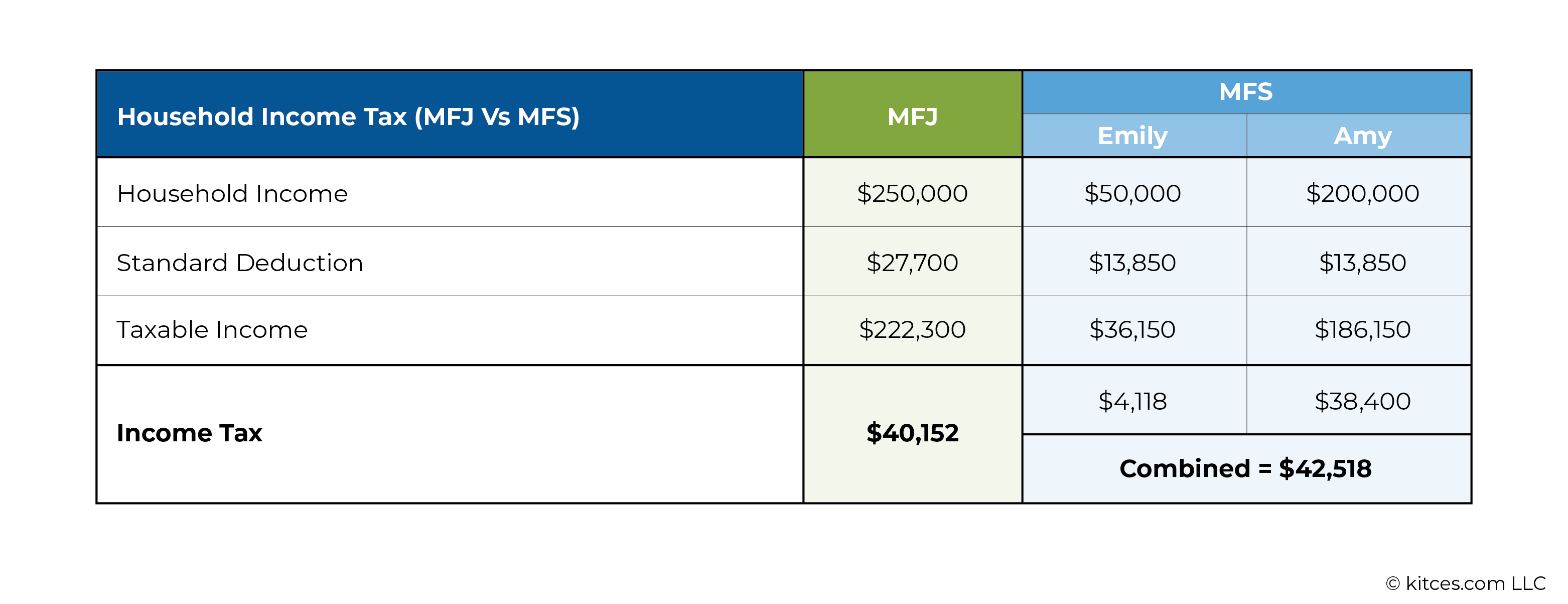

The comparison isn't finished until factoring in the tax impact of choosing MFS status. Assuming that Emily and Amy have no other income or deductions and take the standard deduction in both scenarios (and looking at only Federal taxes since New Hampshire has no state income tax), here is how their taxes would break down:

Finally, putting together the effects of filing separately on student loan payments with taxes:

In this scenario, even after factoring in the higher taxes that come along with MFS status, the decision to file separately would save the couple a total of $16,477.50!

Notably, the tax impact of MFS status can get complex: Certain tax credits, including the Child and Dependent Care Credit, American Opportunity Credit, and Lifetime Learning Credit (among others), are disallowed; the deductions and exclusions for student loan interest and qualified U.S. Savings bond interest income are also disallowed; both spouses must either take the standard deduction or itemize deductions (i.e., one spouse can't itemize while the other takes the standard deduction); and if there are children or other dependents, there needs to be care taken in deciding which spouse will claim them on their return. Different states also have different rules around filing status that would need to be accounted for as well.

Running the numbers in each scenario is important to understand the full impact of filing jointly versus separately. However, the key thing is that there is a comparison that can be made in the first place, now that filing separately can make a difference for borrowers on the REPAYE/SAVE Plan, and many borrowers who may have previously chosen other repayment plans like IBR and PAYE instead of REPAYE because doing so wouldn't have allowed them to exclude their spouse's income might want to reconsider now whether it would be better to switch to REPAYE (and eventually, to the SAVE Plan).

Elimination Of Negative Amortization

As promised in the original announcement of the new IDR plan, the SAVE Plan subsidizes borrowers' student loan interest so that if their required monthly payment doesn't fully cover the interest charged for that month, the remaining interest isn't added to the principal of the loan. Previously, under REPAYE, borrowers' interest was only 100% subsidized during the first 3 years of the loan, with the amount reducing to 50% thereafter, while other repayment plans don't subsidize interest at all after the first 3 years.

This matters because, although many borrowers will have their loans forgiven after they complete their full repayment period of 10–25 years, regardless of whether their interest is subsidized or not (more on loan forgiveness below), the amount of the loan that is forgiven is usually included as taxable income in the year of forgiveness. If the loan balance is steadily growing even as the borrower is making all of their payments (known as 'negative amortization'), it's possible for someone to be taxed on more than the original amount of their loan, even after making a decade or more of on-time payments.

With interest rates today much higher than they were in early 2020 when most people last made student loan payments (and higher than they've been since the early 2000s), the interest subsidization feature of the SAVE Plan is that much more important for borrowers who are likely to see their loans forgiven. Although notably, for borrowers working towards Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), which involves having loans forgiven tax-free after 10 years of making required loan payments while working in an eligible public service job, it doesn't matter as much whether their loan balance is growing or not – but the interest subsidization feature is still nice to have in case the borrower moves to a different job that isn't eligible for PSLF (and other aspects of a borrower's financial life, like their credit score, might also be affected by the overall balance of their loan).

Expanded Forgiveness Options With The SAVE Plan

Under the existing IDR plans, borrowers can have their loans forgiven after making payments for either 240 months (20 years) or 300 months (25 years), depending on their repayment plan.

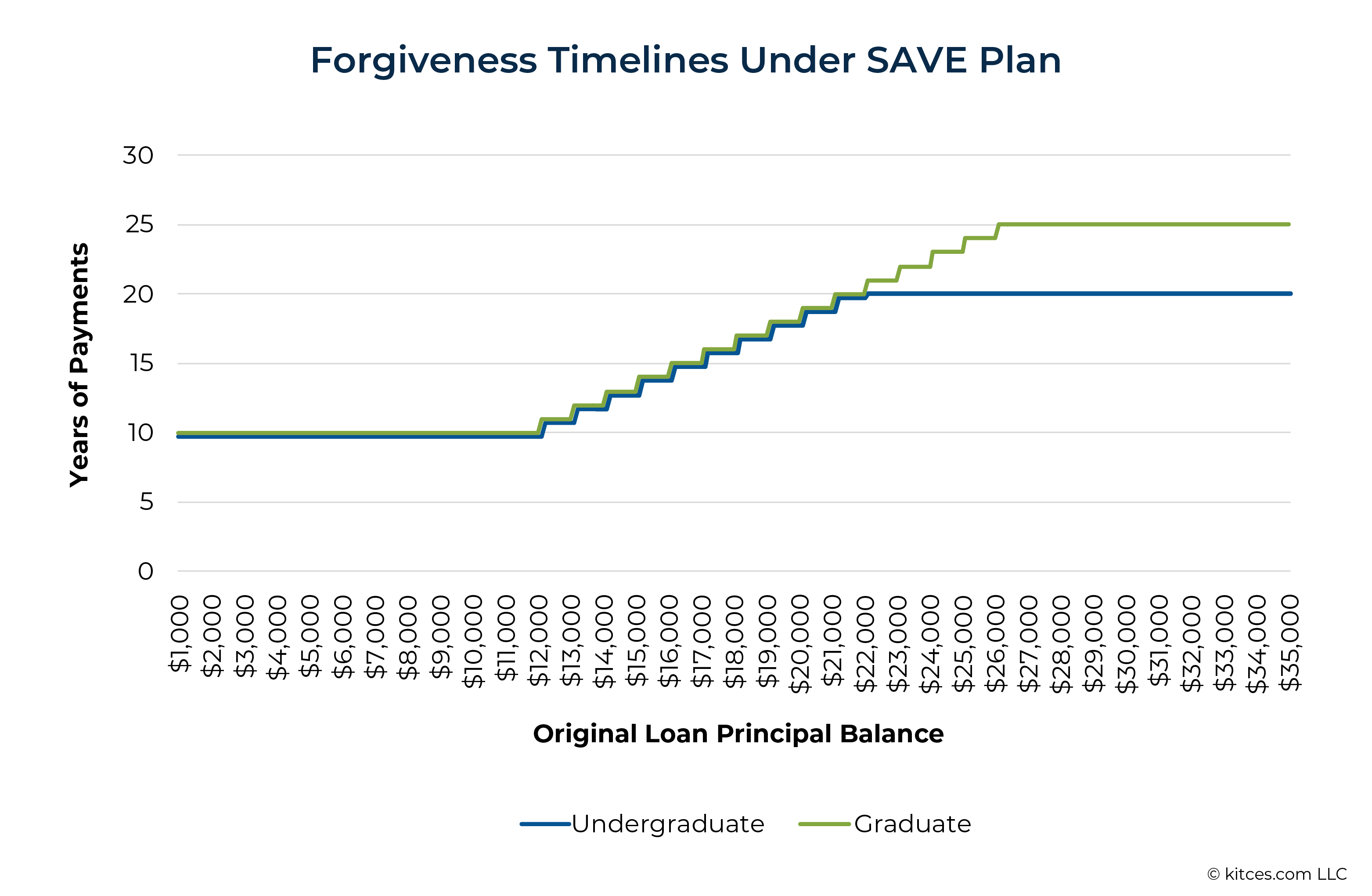

The SAVE plan retains REPAYE's forgiveness schedule of 20 years for borrowers with only undergraduate loans and 25 years for those with any graduate loans, but adds one additional tier: If the combined original balance of all loans – undergraduate and graduate – being paid under the plan was $12,000 or less, the loans are forgiven after making payments for only 120 months (10 years).

For loan balances that exceed $12,000, 12 monthly payments are added for each additional $1,000, meaning that, as shown in the graph below, loan balances between $12,000 and $21,000 (for undergraduate loans) and $26,000 (for graduate loans) will be forgiven sometime between 10 and 25 years.

Forgiveness Granted After 20 Years Of Monthly Repayment:

- IBR (new borrowers after 7/1/2014)

- PAYE

- REPAYE (when only repaying undergraduate loans)

- SAVE Plan (for original undergraduate loans greater than $21,000; sooner for lower balances)

Forgiveness Granted After 25 Years Of Monthly Repayment:

- ICR

- IBR (borrowers before 7/1/2014)

- REPAYE (when repaying at least 1 loan for graduate or professional studies)

- SAVE Plan (for original graduate loans greater than $26,000; sooner for lower balances)

In addition to the new 10-year forgiveness timeline for smaller loan balances, the Department of Education's new regulations expanded the criteria for months that get credit towards loan forgiveness (which notably apply to all IDR plans, not just REPAYE and/or the new SAVE Plan).

Previously, the only months that counted towards forgiveness were those in which the borrower either:

- Made a required payment under their current repayment plan (including months when the required monthly payment was $0);

- Made a payment under a different repayment plan (either an IDR or the standard 10-year repayment schedule);

- Had received an economic hardship deferment and weren't required to make payments (including time spent serving with the Peace Corps).

The new regulations significantly expand the list of deferment and forbearance periods that can be counted towards forgiveness. In addition to the items above, the list now includes:

- Deferments for cancer treatments;

- Deferments for rehabilitation training programs;

- Unemployment deferments;

- Military service and post active-duty student deferments;

- National service, national guard duty, and Department of Defense Student Loan Repayment forbearance; and

- Administrative and bankruptcy forbearance.

For other deferment or forbearance periods not on the above list – but notably excluding deferments for borrowers who are still in school or who go back to school at least half-time – borrowers can make catch-up payments within 3 years of the original due date of the payment (beginning after July 1, 2024) and still receive credit for those months.

Additionally, under the old rules, any time a borrower consolidated their loans into a Federal consolidation loan, doing so reset the clock for forgiveness. For instance, if a borrower consolidated their loans from FFEL loans to a Direct Consolidation loan in order to qualify for an IDR plan other than IBR (which is the only plan for which unconsolidated FFEL loans are eligible), they would have now been stuck with a brand-new 20- or 25-year timeline for their loans to be forgiven.

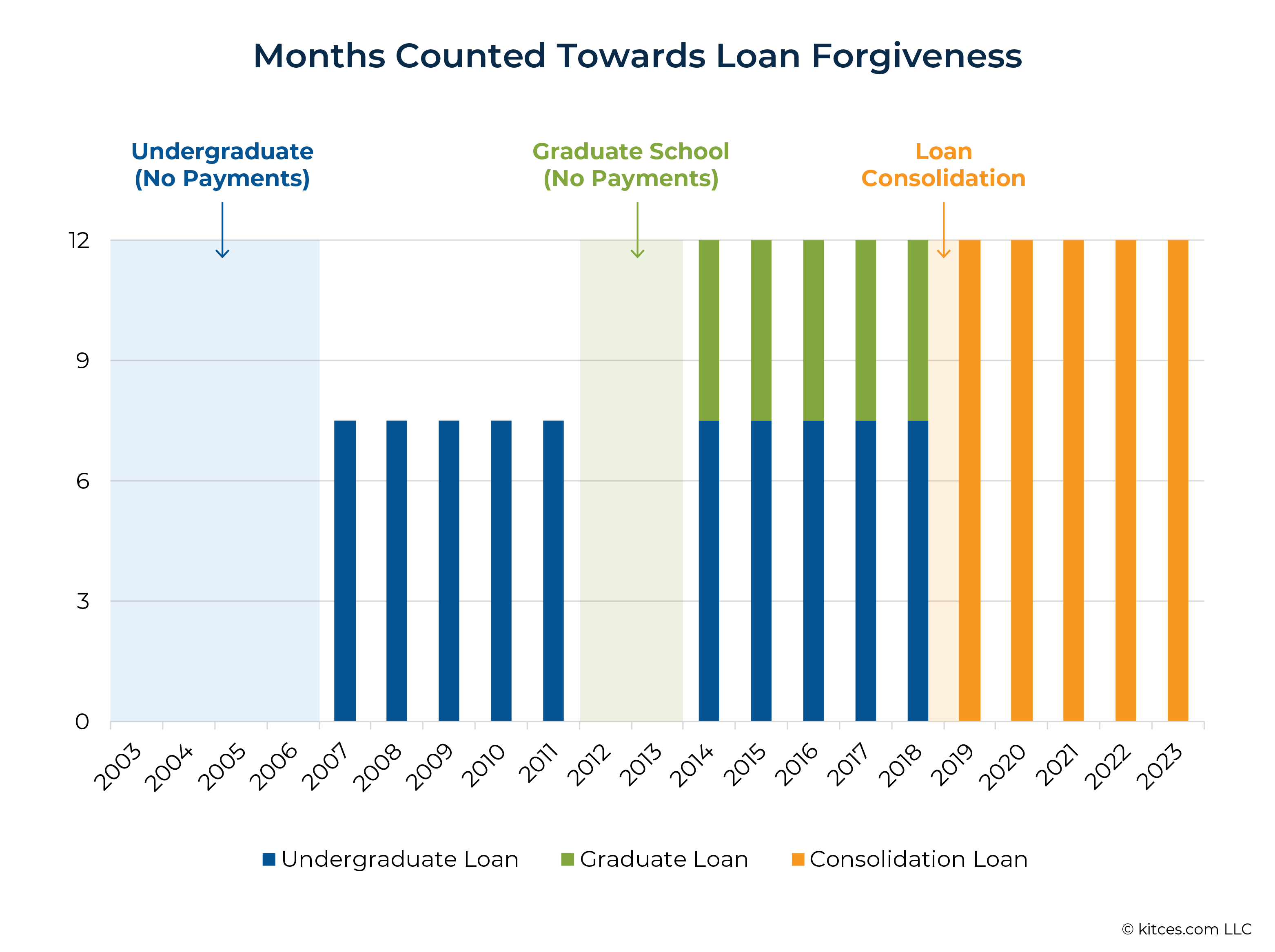

With the new rules, however, payments made on Federal loans prior to consolidation do qualify towards forgiveness for the consolidation loan. The number of months credited prior to consolidation is equal to a weighted average of each of the original loans' initial principal amounts times the number of payments (or other qualifying months as shown in the list above) made on that loan prior to consolidation, rounded up to the nearest month.

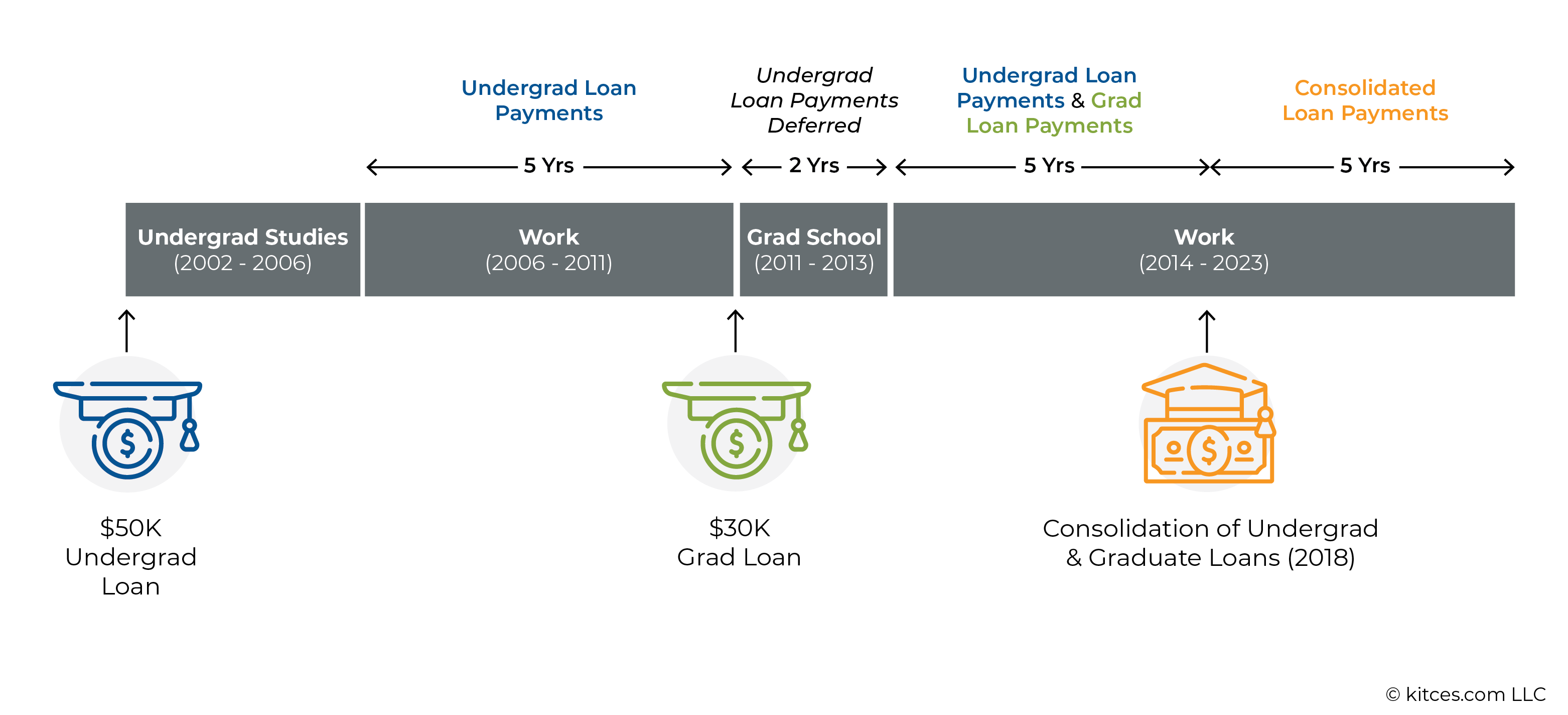

Example 4: Jerrod took out $50,000 of Federal FFEL student loans in 2002 when he began studying for his undergraduate degree. After graduating in 2006, he worked and made his monthly undergraduate loan payments for 5 years.

In 2011, Jerrod went to graduate school and added another $30,000 in Federal Direct loans. After 2 years of graduate school (during which he deferred his payments on his original undergraduate loans), Jerrod worked and made monthly payments on both loans for another 5 years.

In 2018, 5 years after earning his graduate degree, he consolidated both loans into a single Federal consolidation loan. He has since made another 5 years of payments on the consolidation loan, bringing us to today.

To find out how much credit Jerrod should get for his loan payments prior to consolidation, first we calculate how much weight the payments for each respective loan should get based on their original principal balance. For his $50,000 undergraduate loan, each payment gets $50,000 ÷ $80,000 = 0.625 months of credit, and for his $30,000 graduate loan, each payment gets $30,000 ÷ $80,000 = 0.375 months of credit.

Prior to consolidation, Jerrod made a total of 10 years (120 months) of payments on his undergraduate loans (the 5 years when he worked between undergraduate and graduate school from 2006–2011, plus the 5 years when he worked from 2014–2018 after finishing graduate school. The years during graduate school during which payments on his undergraduate loan were deferred don't get any credit).

Additionally, Jerrod made 5 years (60 months) of payments on his graduate loans while he worked from 2014–2018 (at the same time he was making undergrad loan payments).

Thus, he gets 0.625 × 120 = 75 months of credit towards forgiveness for making payments on his undergraduate loan, and 0.375 × 60 = 22.5 months of credit towards forgiveness for making payments on his graduate loan.

In total, then, Jerrod gets 75 + 22.5 = 97.5 months, or 98 when rounded up to the nearest month, of credit toward forgiveness for the period before he consolidated his loans.

Added to the 5 years (60 months) of payments he has made since consolidation, he has a total of 98 + 60 = 158 months of credit out of the total of 300 that he needs to be eligible for forgiveness. Assuming he makes all required payments going forward (or qualifies for one of the deferments above), he would be eligible for forgiveness in May of 2034.

Notably, under the old rules, the forgiveness clock would have been reset in 2018 when he consolidated his loans, and he would only have credit for the 60 months of payments he's made since then – meaning he wouldn't be eligible for forgiveness until 2043!

In other words, getting credit for his pre-consolidation payments saved Jerrod 9 years of additional payments.

Other IDR Plans Are Being Phased Out For New Borrowers

Given how generous many of the features of the new SAVE Plan are compared with other IDR plans, it was speculated early on that it might be relatively restrictive in its eligibility requirements and that only the neediest student loan borrowers (or, as in other IDR plans, only new borrowers as of a certain date) would be allowed to take advantage of its features.

Instead, nearly the opposite is true. Not only is the SAVE Plan open to any borrower with Federal Direct loans, regardless of the date the loans were disbursed – but the new regulations are also making it more restrictive to opt into other IDR plans, to the extent that after 2024 the SAVE Plan will be virtually the only IDR plan used by new student loan borrowers.

Of the other IDR plans, REPAYE as it currently exists is going away entirely sometime in 2023 (to be replaced by the SAVE Plan); and starting July 1, 2024, PAYE will be closed to all new borrowers (including borrowers switching from another plan), ICR will be closed to all new borrowers (except those with Direct Consolidation loans used to repay Parent PLUS Loans), and while IBR will still be open to new enrollees, borrowers will be prohibited from switching into that plan if they have made at least 60 monthly payments on the REPAYE/SAVE plan after July 1, 2024.

Starting next summer, then, only the SAVE and IBR plans will be open to new enrollees, while new and existing borrowers will have until July 1, 2024, to decide whether they want to opt into the PAYE or ICR plans while they still can.

Choosing Between SAVE And IBR

The Department of Education's new regulations significantly narrow the number of IDR plans available to new borrowers after they fully take effect on July 1, 2024, but there will still be a choice for borrowers to make between the new SAVE Plan and the existing IBR plan. While the SAVE Plan's terms are pretty generous, as described above, and would likely be the top choice for many borrowers, there are still some reasons that a borrower would want to opt into the IBR plan as well.

The 1st reason might come down to eligibility. The IBR plan, unlike SAVE, can be used for non-consolidated FFEL loans. And while borrowers can always consolidate their loans to become eligible for the SAVE Plan, there are reasons they may want to avoid doing so (for instance, any unpaid accrued interest on an IBR loan will be added to the loan principal when it is consolidated).

The next reason is that, in some cases, borrowers could actually have a lower loan payment with the IBR plan than with the SAVE plan. That's because loan payments under IBR are capped at the amount they would be under the standard 10-year payment plan, while the SAVE Plan has no such payment cap. So for borrowers with especially high incomes (or conversely, with lower loan balances), the IBR could result in a lower payment.

Example 5: Winnie is a single tax filer in Ohio who earns $500,000 per year. 10 years ago, she took out $100,000 in loans for her undergraduate degree at a 6% interest rate and enrolled in the IBR plan to pay them off.

Under the IBR plan, Winnie's required payment is the lesser of 10% of her discretionary income or the monthly payment under the 10-year standard repayment plan. Given that her current discretionary income equals is $500,000 – (150% × $14,580) = $478,130, her monthly payment based on discretionary income would be calculated as (10% × 478,130) ÷ 12 = $3,984.42. The 10-year standard loan payment would be calculated as $1,110.21 (by solving for the time-value-of-money payment variable with terms n = 120, i = 6% ÷ 12, and PV = –$100,000). And because Winnie's required payment is the lesser of these 2 results, her monthly payment is $1,110.21.

Under the SAVE Plan, Winnie's required monthly payment would be 5% of her discretionary income, or (5% × ($500,000 – (225% × $14,580))) ÷ 12 = $1,946.65.

In other words, Winnie's minimum payment would be $1,110.21 on the IBR plan versus $1,946.65 if she were to switch to the SAVE Plan. So by staying in the IBR plan, Winnie would save $1,946.65 – $1,110.21 = $836.44 per month, or $10,037.28 per year!

The 3rd reason is that, starting July 1, 2024, the IBR plan will be the only IDR option available to borrowers who are currently in default on their loans. Borrowers on IBR who become current on their loans and who make payments for at least 3 months can then enroll in the SAVE Plan.

Below are some key highlights of each plan as borrowers compare their current options.

Timeline Of The SAVE Plan Rollout

The new SAVE Plan is effectively being implemented in 2 phases, the first being this summer in advance of the restarting of student loan payments, and the second beginning on the plan's 'official' start date of July 1, 2024.

The upshot is that only some of the changes will be in effect when student loan payments resume in October 2023, while others won't kick in until July 2024. For example, borrowers whose loans would be eligible for forgiveness under the SAVE-plan's new 10-year forgiveness timeline will need to wait until after July 1, 2024 to actually receive forgiveness.

Other Notable Student Loan Announcements

Aside from the rollout of the new SAVE Plan, there were 2 additional important announcements that will potentially affect student loan borrowers preparing to restart their payments this Fall:

- The implementation of a new integration with the IRS to automate the annual income and family recertification process for borrowers on IDR plans; and

- The announcement of a yearlong "on-ramp" period for borrowers having trouble making their payments.

Automation Of Recertification Process Via IRS Authorization

Borrowers on Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans are required to recertify their income and household size each year in order to confirm and/or recalculate their required payment amount. Traditionally, this was a manual process for each borrower that involved filling out the IDR application and providing tax information each year, which made it easy to forget – and failure to recertify generally means being booted off the IDR plan (and generally onto the standard 10-year repayment plan) until recertification is completed.

This year, however, the Department of Education has collaborated with their fellow bureaucrats at the IRS to give borrowers the option for the first time to automate the recertification process. When filling out this year's recertification application, borrowers can check a box to provide approval for the Department of Education to access the borrower's tax return information directly from the IRS, and each year henceforth, the recertification will be done automatically without the borrower needing to remember to do it themselves. The Department of Education and/or the borrower's loan servicer will send a reminder each year, giving borrowers the option to manually recertify, but if they forget to do so, they won't face the prior consequences of missing the recertification deadline.

"On-Ramp" Period For Restarting Loan Payments

One of the biggest potential issues of the 3 ½-year-long pause in student loan payments is that those payments have been 'absorbed' into borrowers' budgets. It's been so long since most borrowers have needed to think about that fixed expense in their lives that when loan payments do resume, many will likely have trouble adjusting – especially given how high inflation over the last 2 years, particularly in housing and fuel costs, has likely filled the space that student loans once occupied with other essential expenses.

Recognizing the reality of the shock to the system that the resumption of student loan payments could represent, the Biden administration announced a 12-month "on-ramp" period running from October 1, 2023, to September 30, 2024. During this period, loan payments will be due and interest will accrue, but if borrowers miss payments, they won't be considered delinquent, placed in default, referred to debt collection agencies, or reported to credit bureaus.

While not the same as further extending the student loan payment pause – an option that is no longer available now that the current August 31 end date has been codified into law – this does give some leeway for borrowers who will have difficulty re-integrating the payments into their budget (particularly if they had been banking on the planned loan forgiveness program actually going through). However, the longer a borrower goes during this period without making their full loan payments, the more they'll need to pay later on in order to catch up – so it's best to only use this option as a last resort, and only if there's a plan to make up the missed payments later on.

What Advisors Can Do To Help Clients Prepare

The first thing that advisors can do is to help ground clients psychologically in the reality that, yes – after many false starts over several years – student loan payments are really going to be a part of their lives again.

Next, it's helpful to take stock of the client's current situation and what will happen if they do nothing between now and the first payment due date in October. Are they currently on an Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan? What were their pre-COVID interest rates and payment amounts? How much time do they currently have left until their loans are paid off or forgiven (either under Public Service Loan Forgiveness or the terms of their IDR plan) – accounting for the fact that the 3 ½-year-long payment freeze counts as time towards forgiveness? Who is even servicing their loan anymore, and do they know how to make payments when they need to?

Now, advisors can start to discuss potential actions with the client to optimize their situation going forward.

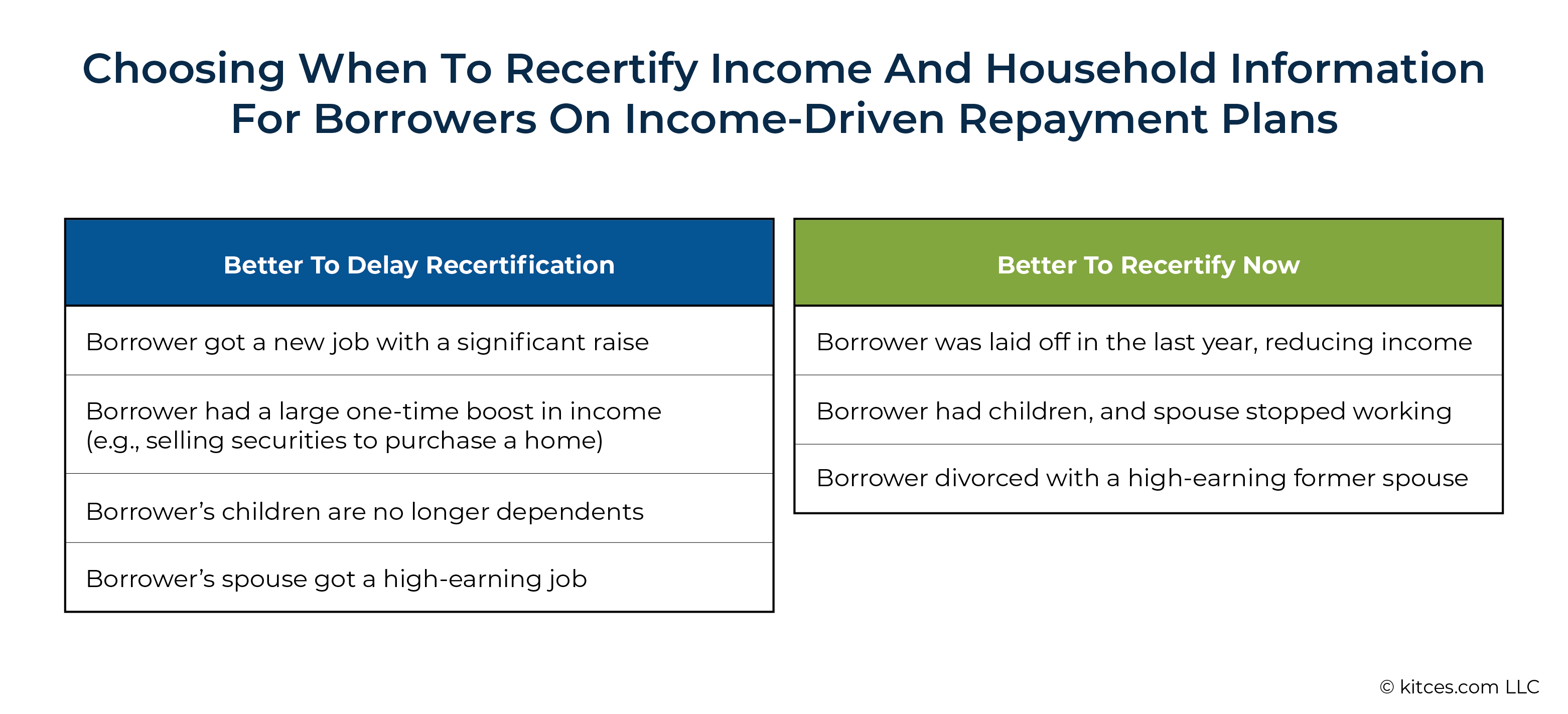

Whether – And When – To Recertify Income

Unless a borrower decides to recertify their income and household information sometime during the repayment pause, their income and household information used to calculate their loan payments likely dates from 2018 or, at the latest, 2019. Needless to say, a lot could have happened during that time: marriages, divorces, children, deaths, new jobs, layoffs, and everything in between.

Just because a borrower's situation has changed, however, doesn't mean they necessarily need to recertify right away. Per the most recent guidance from the Department of Education, the earliest date that borrowers are required to recertify is 6 months after the end of the loan pause, which in this case would be March 1, 2024. Depending on the borrower's recertification date (which is usually based on the date they entered into the IDR plan), some borrowers won't need to recertify until early 2025 (although if they want to enroll in a different IDR plan, other than borrowers currently on REPAYE who will be automatically enrolled into the SAVE Plan, they'll need to recertify their income when they fill out the application for the new plan).

A lot can go into the decision of whether to recertify income. In general, events that have caused income to decrease and/or household size to go up will likely decrease a borrower's monthly payments under an IDR plan, while events that increase income and/or decrease household size will increase their payments. If payments would be set to increase after recertification, it might make sense to delay it as long as possible; while if recertifying would lower the monthly payment from what it was prior to the pause, it could be better to do so sooner than later.

Some examples include:

If a borrower has experienced a major change in their income or household number that isn't reflected in their most recent tax return (e.g., they were laid off from their job this year, which wouldn't be reflected on last year's tax return), the Department of Education has provided a temporary option for borrowers to self-report their income without providing tax documentation, which will last until 6 months after the end of the payment pause (March 1).

Which Repayment Plan To Use

As discussed earlier, although the new SAVE Plan is often generous in its terms, it still isn't always the right plan for everyone. Earners on the IBR or PAYE plans whose incomes have increased significantly may be better off staying with those plans, given that their payments are capped at the standard 10-year payment amount while the SAVE Plan isn't. Those who expect a significant increase in income in future years may also want to consider switching to either IBR or PAYE (since PAYE will be closed to new borrowers on July 1, 2024, while IBR will be closed to those who make more than 60 payments to the REPAYE/SAVE plan after July 1, 2024).

Conversely, however, borrowers who had previously been on other IDR plans – for instance, couples who enrolled in IBR in order to take advantage of the ability to exclude spouses' income by filing MFS – might find it worth reevaluating the REPAYE plan since it (and its successor the SAVE Plan) will now allow borrowers filing separately to leave off their spouse's income.

Whether To File Separately

In the years before 2020, student loan planning was a major reason for couples to use the Married Filing Separately (MFS) filing status, given that it allowed borrowers on the IBR and PAYE repayment plans to exclude their spouse's income for the purposes of calculating their payment. But during the pandemic years and associated student-loan-payment pause, there was little reason to file separate returns, especially when doing so would have likely resulted in higher taxes compared to Married Filing Jointly (MFJ) without the offsetting benefits of lower student loan payments. So, many couples who had previously filed separate returns may have eventually switched to MFJ, and newly married couples simply started filing MFJ without giving much thought to potential student loan planning considerations.

However, now may be a good time to reevaluate those filing status decisions and begin to plan around what to do for the 2023 tax year. Doing so might require running the numbers for both MFJ and MFS scenarios, comparing potential student loan payments with tax liabilities, and setting the table for decisions like which spouse would claim any dependents and whether it makes more sense for both spouses to itemize or take the standard deduction. Filing separately isn't a decision to take lightly, given the different treatment of many tax credits, deductions, and tax brackets, and it's never too early to start planning to ensure it's really the best decision when putting both the student loan and tax situations together.

While it's too late to file separately for 2022 (MFJ returns can only be amended to MFS before the original due date of the return, with no extensions), borrowers who may benefit from filing MFS whose most recent returns are MFJ may want to avoid recertification until after filing a 2023 return (as MFS) if possible.

After years of speculation about when student loan payments would really resume and, more recently, which parts of the Biden Administration's student loan relief plan would make it past legal challenges, there's finally some clarity into what life with student loan payments back in force will look like. Many borrowers are likely disappointed with the Supreme Court's decision to reject one-time debt forgiveness, but there's still occasion for optimism in the fact that, with good planning around the new SAVE Plan, borrowers can potentially save more (and perhaps much more) than the $10,000 that was originally slated to be forgiven.

Ultimately, though, while student loans are an unpleasant reality for many borrowers – with the complexity of the many different plans and the choices involved causing no small amount of overwhelm – advisors can provide tremendous value in creating a clear path forward that minimizes the pain of resuming loan payments. And with the resumption of payments now just a few months away in October, now is the time to act to make sure the clients can make the transition back into student loan payments as smoothly as possible!

Leave a Reply