Executive Summary

There are many tax planning strategies that allow financial advisors to demonstrate the ongoing value they provide to clients in exchange for the fees they charge. Part of this value is understanding the detailed nuances that make a strategy effective and implementing it correctly, avoiding issues with the IRS down the line. For instance, while backdoor Roth conversions are a well-known strategy, many individuals have either missed the opportunity to use it and/or implemented it incorrectly – which, left uncorrected, can result in unnecessary headaches, taxes, and even penalties – presenting an opportunity for advisors to add significant value for their clients.

The backdoor Roth strategy can be valuable for clients whose high income levels preclude them from making regular contributions to a Roth IRA. As while income phaseouts apply to contributions made to a Roth IRA, there are no such limitations on contributions made to a traditional IRA, nor on conversions from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA (since 2010). Thus, the strategy itself consists of a 2-step process involving 1) a contribution (either deductible or non-deductible) made to a traditional IRA, followed by 2) conversion into a Roth IRA.

While this process might seem relatively straightforward, there are many reporting requirements for non-deductible IRAs (through IRS Form 8606) and numerous IRS rules around timing and accounting that can quickly turn this seemingly simple strategy into a literal lifetime of extra paperwork filing required of the taxpayer if completed incorrectly. For instance, if the client has existing IRA dollars and/or if they plan to rollover funds from a qualified account at any point during the year, backdoor Roth conversions can be complicated significantly. This is mainly because of the IRA Aggregation Rule, stipulating that when determining the tax consequences of an IRA distribution (which includes a conversion), the value of all IRA accounts will be aggregated together for the purpose of any tax calculations (turning a 'clean' backdoor Roth into a messy partial Roth conversion!).

To avoid this situation, before recommending a backdoor Roth, advisors need to make sure they know about every IRA dollar (everywhere in all accounts), review prior tax returns for Form 8606, and confirm that there will not be any rollovers during the remainder of the current year. For clients with a tax-free basis in an IRA, options to remove the taxable gain portion (and become eligible for a 'clean' backdoor Roth) include converting the balance to a Roth (which could be done over multiple years) or rolling the pre-tax funds into a company retirement plan or Solo 401(k) (though not a SIMPLE or SEP as they are lumped in with traditional IRAs for the pro-rata rule).

Advisors also can support the backdoor Roth process by communicating with clients' tax preparers about the strategy and why they are recommending it for their mutual client. Because while advisors might recognize the long-term benefits of having money in Roth accounts, the process does not come with a current-year benefit that may be immediately apparent to the tax preparer; furthermore, it requires tax preparers to complete additional forms (which they may not appreciate if they’ve not bought into the long-term 'why' themselves).

Ultimately, the key point is that while backdoor Roth conversions can be a valuable strategy, it comes with significant rules and nuances that, if not fully understood, have the potential to cause onerous tax complications for clients in the future. Which means that advisors can add significant value by working together with clients and their tax preparers to ensure that the backdoor RIA process is completed correctly!

Financial advicers – those advisors who are in the business of providing financial advice and who create value through the advice they give (and not through the sale of particular products) – are always on the lookout for planning opportunities and strategies that will help clients achieve their financial goals. As an added benefit, these strategies help demonstrate the ongoing value that advicers provide to clients in exchange for the fees they charge. However, regular consumers of technical content can sometimes become desensitized to the strategies that 'everybody already knows', sometimes to the point of taking them for granted, or worse yet, overlooking the detailed nuances that make the strategies effective and implementing them incorrectly.

One such strategy includes the seemingly universally known backdoor Roth strategy, which involves the conversion of funds in a traditional IRA into a Roth IRA, benefitting taxpayers who may be ineligible to make direct contributions to a Roth IRA (e.g., individuals whose income levels exceed the Roth IRA threshold limits). After all, this strategy has been around for years and it seems that every financial planning author, journalist, blogger, podcaster, and social media influencer has produced content on the topic.

However, despite this being a universally 'known' strategy, in my role as a CPA and tax preparer, I review hundreds of returns each year, many from clients with Advicers, who have missed this opportunity and/or who have implemented it incorrectly, which if left uncorrected, will result in unnecessary headaches, taxes and even penalties (all of which have the compounding effect of diminishing the Advicers value to their client).

When Is The Backdoor Roth Even Worth Doing?

Before reviewing the rules and strategies for efficiently and effectively using the backdoor Roth strategy, let us first address the concern raised by many advisors, clients, and tax preparers, which is some variation of, "This sounds like a lot of work for $6,500!" Actually, many tax preparers will likely say something like this to their client: "Your advisor made this big mess of your taxes and you don't even get to deduct it! If you had just made an IRA contribution, you would have saved thousands in taxes." (This is an actual quote from a tax professional!)

Going around to the back door makes sense when you can’t get in through the front. Making backdoor Roth contributions is an extension of the broader decision that going with a Roth makes sense for a particular taxpayer. For taxpayers who are concerned they will be in a higher tax bracket in the future, either because their income increases or because tax laws change, backdoor Roth contributions can be a great tool for filling up their tax-free bucket. Advisors should first explore contributory Roth options through employer sponsored retirement plans (which don’t have the income limits that Roth IRAs do) and verify the taxpayer can’t make direct Roth IRA contributions before beginning backdoor Roth contributions.

To help both clients and tax preparers understand the backdoor Roth strategy value of 'just' $6,500 annually, financial advisor Michael Henley illustrates how advisors could open the conversation as follows:

Ms. Client, whereas your tax preparer is focused almost exclusively on last year, one of my jobs is to keep you ahead of the IRS for decades.

If my team coordinates backdoor Roth contributions of $6,500 for you in each of the next 20 years, and let's say (for easy math) that it grows at 10% annually, we could have a tax-free bucket of some $370,000. Which, in round numbers, would save you some $50,000 in taxes.

Would it be OK with you if my team takes care of this for you, even if it requires you to sign a couple of forms?

Whereas a client or tax preparer may understandably feel that $6,500 is hardly worth the effort, knowing it can cumulatively add up to a tax-free bucket of $370,000 (double, if married) suddenly feels very inspiring. However, even the most beneficial tax strategy only counts if the Advicer can get the client to take the action required to implement the strategy.

The Backdoor Roth Strategy Sounds Great, But What Exactly Is It?

It's important to first acknowledge that the backdoor Roth IRA contribution is not officially a 'thing', at least not to the IRS, but rather a tax loophole that the IRS and Congress know about but have chosen not to close (thankfully, the IRS has acknowledged that taxpayers are using this strategy and has not made any focused effort to prevent or crack down on it).

More specifically, the backdoor Roth IRA strategy consists of a 2-step process involving 1) a contribution made to a traditional IRA, followed by 2) conversion into a Roth IRA. This process is designed to get annual contributions into a Roth IRA for taxpayers whose income levels surpass the Roth IRA contribution phaseout range, precluding them from making these contributions. For 2023, the income phaseout for a taxpayer (Married Filing Jointly) making contributions to a Roth IRA ranges from $218k to $228k of Modified AGI (reported on Form 1040 Line 11, with some adjustments).

Nerd Note:

Individuals who are covered by an employer's retirement plan and whose income exceed certain levels (limiting the amount they are able to deduct for their contribution to a Traditional IRA) use the backdoor Roth IRA strategy by making non-deductible contributions to an IRA, which add a level of complexity to the process as addressed in the following sections. However, Backdoor Roths can also involve deductible contributions made to a Traditional IRA (e.g., for those who make too much to contribute directly to a Roth IRA, but who are not an active participant in an employer retirement plan). The net result would be the same (the taxpayer gets a pre-tax deduction on their contribution, and then the conversion is counted as taxable income, the income is offset by the deduction, and the net tax result is the same after-tax Roth contribution equivalent), but the scenario is simpler (no after-tax dollars to report, track, etc.).

As while these income limitations apply to contributions made to a Roth IRA, there are no such limitations on contributions made to a traditional IRA. Furthermore, what makes the backdoor Roth strategy work is that while Roth IRA contributions have income limitations, Roth IRA conversions do not (since the conversion income limits were repealed effective in 2010).

Example 1: Bob & Sue are clients whose Modified AGI of $250,000 puts them well over the top of the Roth contribution phaseout for Married Filing Jointly taxpayers.

Advisor: Bob and Sue, for reasons unknown to me, Congress has decided that you make too much money to take advantage of the tax-free benefits provided to everyone else by a Roth IRA.

However, there is still great news: Congress has left open a 'backdoor', which still allows us to contribute to a Roth account each year, albeit with an extra step, sometimes known as a 'backdoor Roth contribution'.

While there are several critical variables (which will be discussed later) for advisors to consider when determining whether the backdoor Roth strategy will make sense for a client whose ability to make deductible IRA contributions is limited, the first step of the strategy is basically accomplished by the taxpayer contributing up to the annual limit ($6,500 in 2023, plus a $1k catch-up over age 50) into a Traditional IRA and designating the contribution as non-deductible.

By virtue of being non-deductible, these funds are now viewed by the IRS as after-tax dollars. The contribution amount, or basis, can be withdrawn tax free (restrictions and penalties on IRA distributions still apply). Again ignoring critical variables, the second step is for this tax-free money to be converted, tax free, into a respective Roth IRA.

Example 2: Bob & Sue, introduced in Example 1, agree to proceed with the backdoor Roth strategy suggested by their advisor.

Their advisor instructs Bob & Sue each to contribute $6,500 into non-deductible Traditional IRAs and then convert those funds into their Roth IRAs.

The end result is that Bob & Sue each now have $6,500 in their respective Roth Accounts despite being ineligible to make direct contributions to those accounts because their income is too high!

Sounds Easy-Ish, But What Are The Critical Variables Involved?

While a backdoor Roth contribution may sound straightforward in principle, there are many reporting requirements for non-deductible IRAs (through IRS Form 8606) and numerous IRS rules around timing and accounting that can quickly turn this seemingly simple strategy into a literal lifetime of headaches and painful reminders if screwed up.

These issues are compounded by the major custodians being unable to track the nontaxable basis portion in the account (which is why most 1099-R Forms – which report distributions made from IRAs and other accounts – have box 2b checked to signify "Taxable amount not determined"), which makes it even easier to mess up the whole process!

The following sections discuss many of the common roadblocks that can complicate the backdoor Roth strategy.

IRS Form 8606 – And The Fun Begins!

Continuing with the earlier example with Bob & Sue, let's assume they started and ended the year with no other IRA dollars (including funds in any SIMPLE or SEP IRAs). Their only activity was contributing $6,500 to their respective Traditional IRAs and then converting those funds into Roth accounts.

Nerd Note:

While the IRS has no specific rules on how much time must elapse between the non-deductible IRA contribution and the Roth conversion, the authors recommend having these transactions at least appear on 2 different statements (e.g., separate months) whenever possible so that in the event of an audit, auditors can more clearly see the steps that were taken. Prior articles on Nerd’s Eye View have suggested time periods as long as 12 months. Again, neither 1 month nor 1 year is an explicit requirement, but the authors' team has sat through IRS audits of backdoor Roths… and the cleaner, the better! It is important to remember on the other side of this that waiting too long can create issues as well. Any earnings that happen before the conversion takes place are taxable.

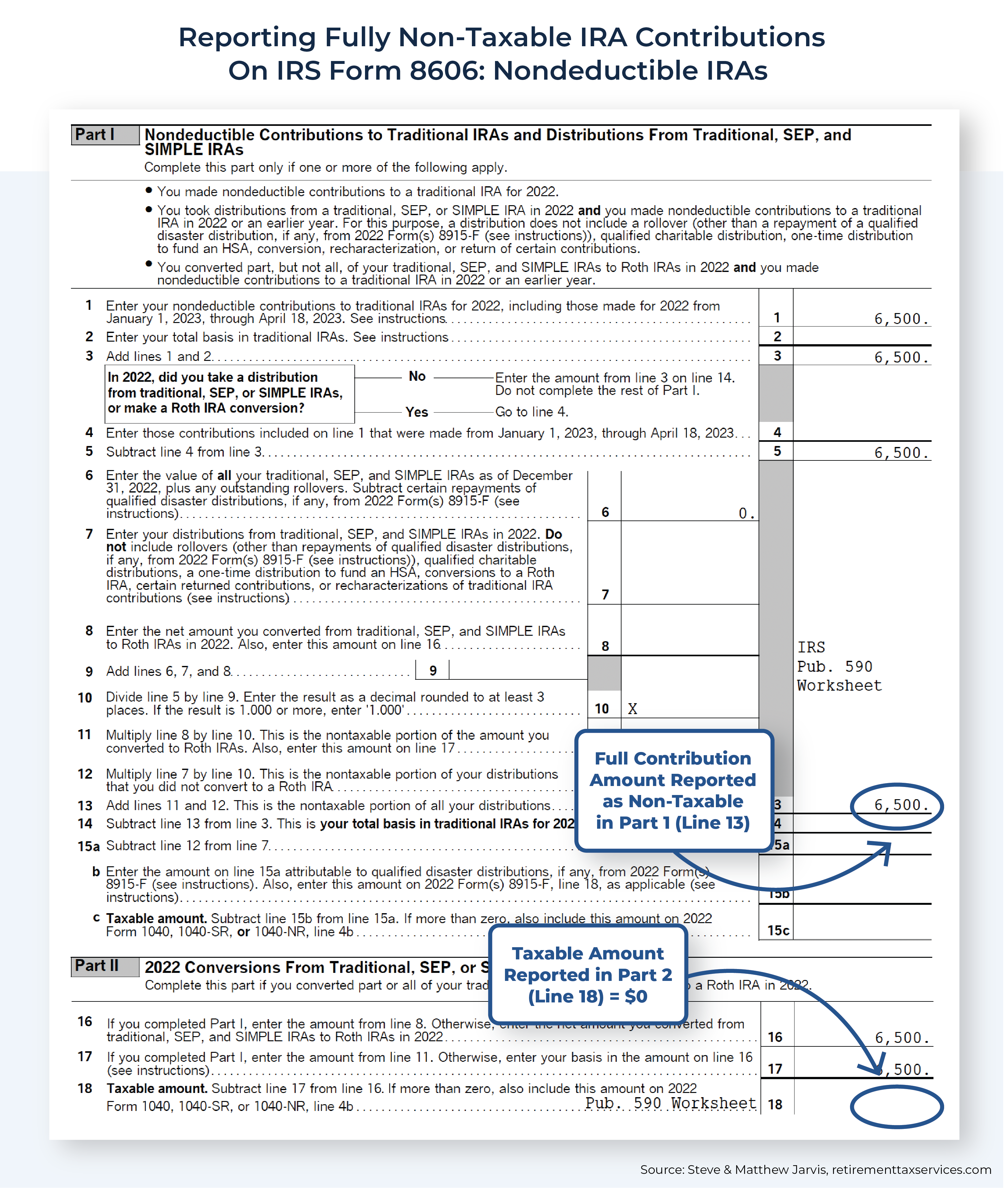

In the case described above, Bob and Sue would each complete their own Form 8606 to be filed with their 1040. Parts 1 and 2 of the form need to be completed; the amount of the contribution will appear on multiple lines throughout the form but, in this situation, will ultimately end with the full contribution and conversion being reported as non-taxable in Part 1 on line 13, and with line 18 in Part 2, which asks for the taxable amount, being blank.

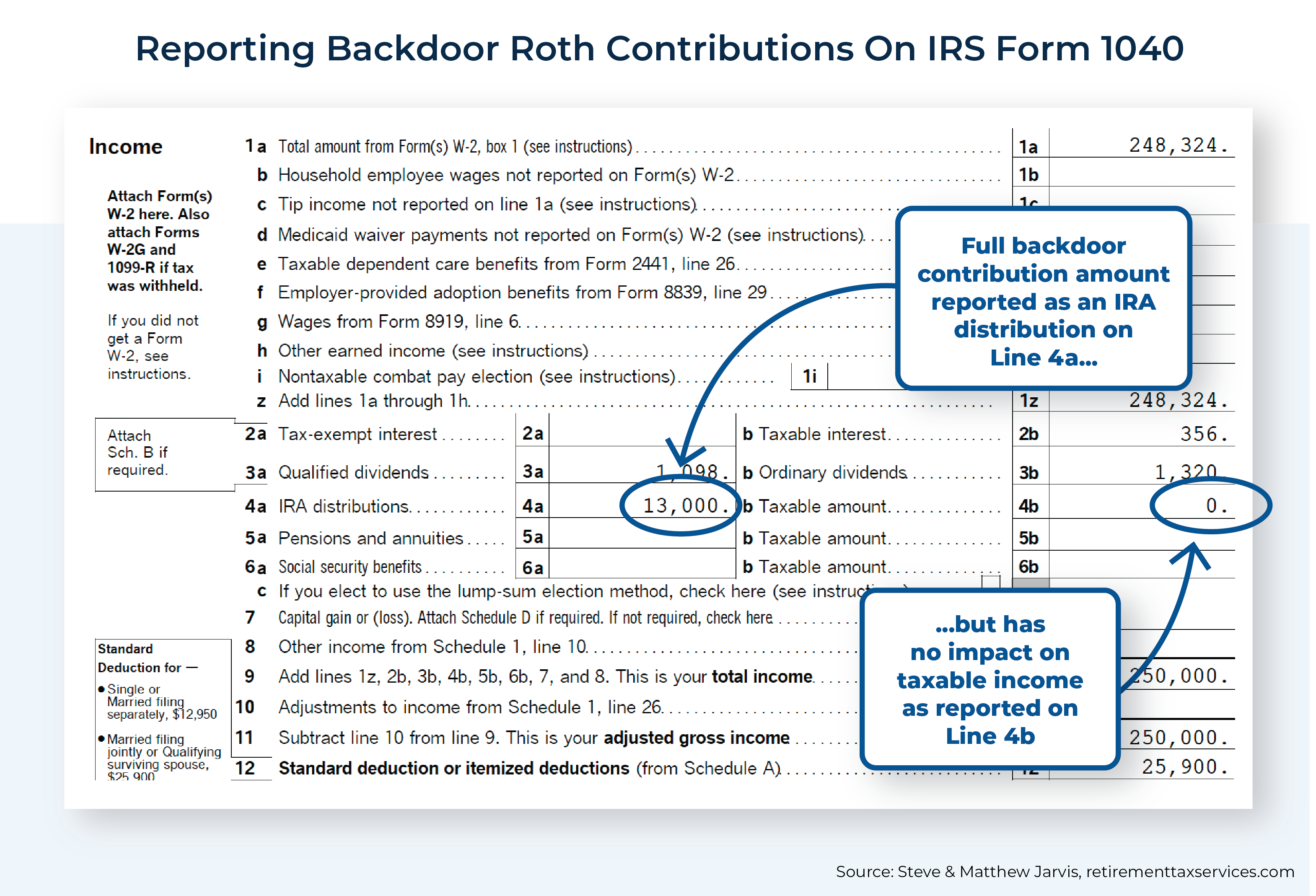

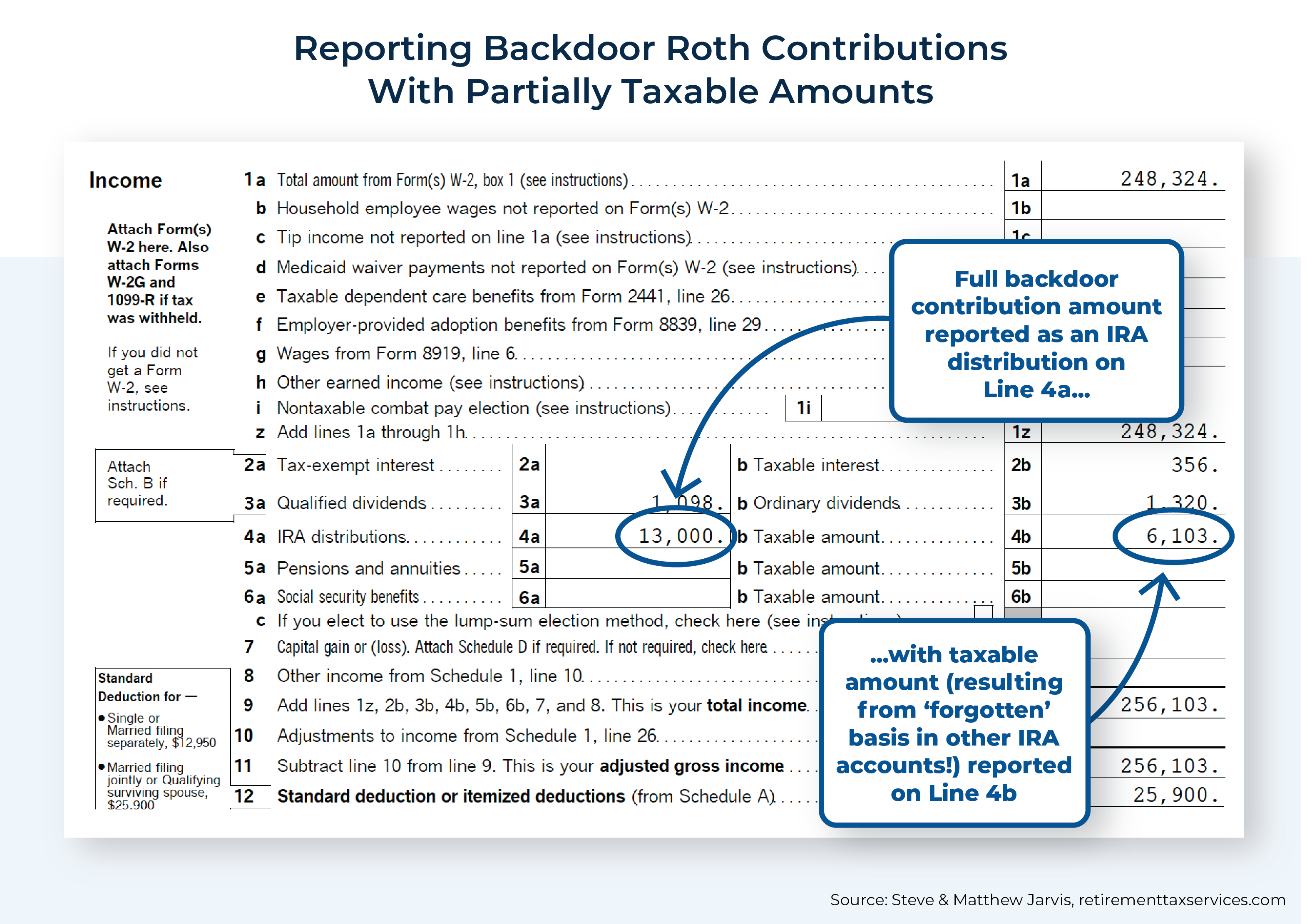

When a backdoor Roth contribution like the one described above for Bob & Sue is executed and reported correctly, there is no impact on taxable income. However, the conversion amounts will be reported as a "distribution" on line 4a of Form 1040 (while being left out of line 4b because it’s a non-taxable conversion of after-tax dollars).

It isn't terribly uncommon to have a scenario as clean as Bob & Sue's. For example, many advisors will have mass-affluent clients with all their qualified funds inside of company retirement plans, which are ignored for the purposes of calculating backdoor Roths (assuming the funds aren't rolled over into an IRA during the year).

Co-Mingling And Cream In The Coffee

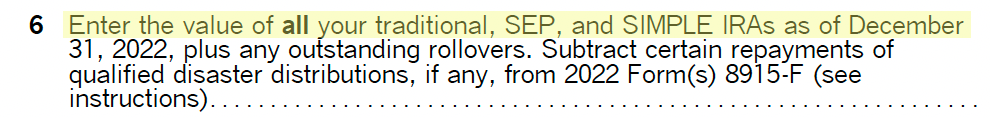

Unfortunately, things get complicated quickly if taxpayers have existing IRA dollars (in any account) and/or if they plan to rollover funds from a qualified account at any point during the year. This is because of the IRA Aggregation Rule under IRC Section 408(d)(2), which stipulates that when determining the tax consequences of an IRA distribution including a Roth conversion – particularly the "pro rata" rule under IRC Section 72(e)(8) and also the early withdrawal penalty under IRC Section 72(t)(1) – the value of all IRA accounts will be aggregated together for the purpose of any tax calculations.

As IRS Form 8606 indicates on line 6: "Enter the value of all your traditional, SEP, and SIMPLE IRAS as of December 31…".

A common mistake made by taxpayers is to open a separate IRA account with the intention of 'holding' the tax-free basis apart from other taxable IRA funds, or assuming that a backdoor Roth can be completed mid-year before they retire in the Fall and then rolling over tax-deferred funds in their 401(k) plan into an IRA well after the mid-year backdoor Roth conversion has been completed.

In either case, the IRS will consider these distributions as pro rata combinations of taxable funds and tax-free basis across all of the client’s IRAs, which will turn a 'clean' backdoor Roth into a messy partial Roth conversion. If the full amount of basis is not converted in a single year, it will have to be tracked and reported until the basis is fully converted or distributed. This creates a reporting requirement that could last for years or decades. In reality, the basis is often forgotten about, resulting in the taxpayer eventually paying taxes on a distribution of the basis that should have been tax free.

Example 3: Bob, from Examples 1 and 2, did a $6,500 backdoor Roth, which his advisor told him would be tax free.

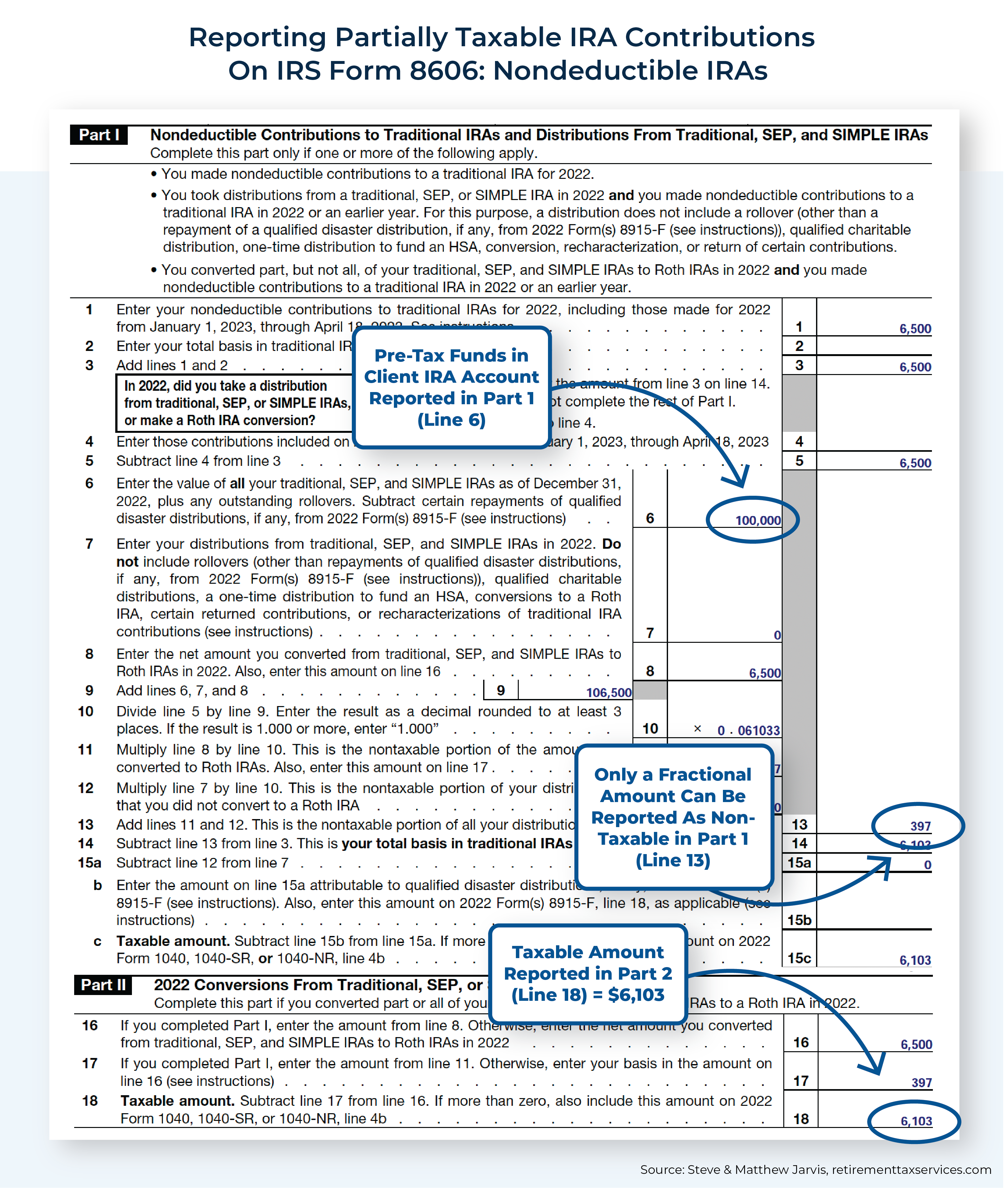

However, upon reviewing Bob & Sue's tax return and accompanying Form 8606, their advisor discovered that the client had $100,000 of pre-tax money in another IRA (this becomes even more complicated if this isn’t discovered until years later).

Because of the $100,000 pre-tax and $6,500 after-tax balances, the combined total account value reported on Line 6 of Form 8606 would be $100,000 + $6,500 = $106,500, which means that every future distribution would be approximately $100,000 ¸ $106,500 = 93.9% taxable and $6,500 ¸ $106,500 = 6.1% tax-free.

So instead of Bob's $6,500 being converted wholly tax free as his advisor originally thought would be the case, what actually ended out happening was that only $6,500 ´ 6.1% = $397 was tax free, and the remaining $6,500 – $397 = $6,103 was taxable!

Instead of reporting $0 as the taxable amount for IRA distributions as originally intended, Bob & Sue now need to report $6,103 as taxable income on their 1040, as follows:

After Bob & Sue's tax preparer corrects their tax return, the tax preparer tells them, "I'm not sure what your financial advisor was thinking, but they really messed this up!"*

An awkward situation for Bob & Sue's advisor.

Notably, this example only covers Bob's situation because the pro-rata rule is applied to taxpayers individually. Only Bob’s IRAs (including SIMPLE and SEP IRAs) would be used to calculate how much of the conversion was, in fact, tax-free. If Sue had a $200,000 IRA as well, Bob’s calculation would not change, but Sue’s form 8606 would have to be updated to include her pro rata calculation.

*An actual quote!

This pro rata distribution rule is often referred to as the "Cream in the Coffee" rule, as once a person pours cream into their coffee, every sip is some portion of cream and coffee, and similarly once non-deductible contributions are mixed into an aggregation of IRAs, every distribution (or conversion) is some portion of non-deductible and taxable. However, unlike a cup of coffee left to sit on the table all day, the 'cream' of an IRA will never separate itself, and the taxpayer will be left with taking and reporting pro rata distributions forevermore, at least until such point they have effectively zeroed out all IRA accounts. Ouch.

To avoid this situation, before recommending a backdoor Roth, prior tax returns must be reviewed for Form 8606 to see if there is already some after-tax 'cream' in the IRA 'coffee' (which, sadly, is not always reliably filed; so even if Form 8606 wasn't filed to indicate the presence of other IRA funds, the taxpayer may still not be in the clear to do a backdoor Roth). More importantly, advisors need to make sure they know about every IRA dollar, everywhere in all accounts, and they need to confirm that there will not be any rollovers during the remainder of the current year.

Accidental & Lost IRA Basis

Another common situation when taxpayers unknowingly end up with tax-free basis in their IRAs is when they were only partially eligible for a deductible Traditional IRA contribution because their income was in the middle of the phase-out range and, instead of reversing the excess contribution, the box was clicked in the tax software to simply leave the extra in as a non-deductible contribution. When this happens, the taxpayer technically has to file form 8606 continually for any year there is a distribution from their IRA to properly calculate and report the pro rata portion of the distribution that is tax-free.

More commonly the basis is 'lost', meaning that it goes unreported and tax will be paid on the same income twice (once when it was contributed because the taxpayer did not receive a tax deduction, and a second time when it is distributed and reported as a taxable because no one told the IRS otherwise).

Not to pile on more complications here, but technically, filing Form 8606 is only required when there is activity to report. As such, if the taxpayer has basis in their IRA account(s) but hasn't taken a distribution, made a contribution, and/or done a conversion in years, it could be years – or even decades! – since Form 8606 was included with their tax return. As such, advisors could easily review the tax returns from the last 2 years, not see a Form 8606 included, and incorrectly assume there was no basis to report!

To prevent this, getting even an oral history from the client describing their IRAs and reconciling that with their Social Security earnings statements to identify potential years over the limits can help advisors identify lost basis. The client’s oral history will at least provide context for whether they have ever contributed to an IRA, and reviewing Social Security statements allows advicers to see how much taxpayers reported as earnings by tax year, which can be compared to the income limits for making deductible IRA contributions to identify tax years that might be worth investigating. This may not be a perfect solution, but it is one that is more likely to be executed than trying to get tax returns for every single year a client has paid taxes. Admittedly, at some point, the light isn't worth the candle of tracking this stuff down… until it is.

Given these complexities, it becomes easier to see why 'everybody knows' about backdoor Roth conversions, yet few people actually understand all of the complex nuances involved in doing them efficiently.

Is It Necessary To Completely Zero Out All IRA Accounts Before Doing A Backdoor Roth Conversion?

Once tax-free basis is introduced to any of a taxpayer's IRA accounts, all distributions will be characterized on a pro rata basis until such time that the 12/31 balance has zero taxable dollars. One method to accomplish a $0 balance would be for the taxpayer to withdraw and/or convert 100% of their IRA balances. Depending on the taxpayer's situation, this could make sense.

For example, when Bob (from earlier examples) retires, his advisor may decide to convert all $106,500 of IRAs (consisting of $100,000 taxable and $6,500 tax-free basis) into a Roth and eliminate the pro rata issue altogether (to mitigate a higher tax hit all in one year, this might be done over a few years instead of all at once).

Alternatively, if instead of $100,000, Bob had $2 million of pre-tax dollars in his IRA, converting everything to Roth accounts might be foolish because of the tax bill that would be immediately due on that large of a conversion. Whatever the dollar amount, the only other option for the taxpayer to remove all taxable dollars from the IRA would be to become a participant in a company retirement plan, Solo 401(k) plan, or SIMPLE 401(k) plan (but not a SIMPLE or SEP IRA, as they are lumped in with traditional IRAs for the pro-rata rule) that accepts IRA rollovers of pre-tax dollars. The taxpayer could then roll the pre-tax funds into their company plan, leaving behind only the after-tax funds, which could then be converted into a Roth account and giving them an IRA balance of $0.

Assuming the advisor ensured their client met all the other rules (including the SEC’s suitability requirements for registered broker-dealers and its fiduciary requirements for RIAs) of moving money in and out of a company retirement plan, and the timing of transfers was right, and their accounting was right, and they didn't get caught by the market moving in the wrong direction mid-transfer, this can and does totally work! But tread carefully.

Why Don't The Custodians Help With This?

When faced with all the complexities around reporting IRA basis, advisors often ask why the custodians (e.g., Schwab, LPL, Altruist, etc.) don't track IRA basis like they do investment basis, and instead, simply check the box on Form 1099R to indicate "taxable amount not determined".

As often as I curse the custodians for issuing yet another amended 1099 (if I were czar of the world, every amended 1099 would have to include a $20 Starbucks card as an apology), there is really no way they could effectively track IRA basis, as when a taxpayer makes an IRA contribution, there is no mechanism in place for them to communicate the tax deductibility status of that contribution to the account custodian. Which means that the custodian would be required to collect and analyze every account holder's tax return if the onus were on them to determine whether contributions were deductible or not. Thus, it is on the taxpayer, usually with the assistance of a financial advisor and tax preparer, to coordinate tracking of IRA basis.

This often leaves the advisor earning their fees by making sure this is all tracked and reported correctly.

OK, I Get Why Custodians Can't Help, But Why Don't Tax Preparers Like Roth Accounts, Let Alone Backdoor Roth Contributions?

As noted earlier, many tax preparers often view backdoor Roth conversions as having zero current-year tax benefit that also comes with the burden of an extra form (i.e., Form 8606) they have to complete (and sometimes even 2 if their clients are married). On top of that, they know that they will have to complete these forms every year for eternity.

As retired U.S. Navy SEAL Jocko Willink might say, "Tax preparer doesn't like your strategy? GOOD! Now you can get more practice getting people to take action on your recommendations!"

For financial advisors who are considering this strategy for their clients, I would recommend they start by contacting their clients' tax preparer, sending them a copy of this article and the simple request: "I read this article and it looked like it might make sense for our mutual client, Bob & Sue. Could I pay for an hour of your time to get your thoughts on this strategy in general and on our process for implementing it with clients?"

Please note this is not an attempt to generate billable hours for my fellow tax professionals. Rather, it is my attempt to help advisors understand that these strategies do cost tax preparers time, as backdoor Roth conversions don't just involve an extra form (or 2 for a married couple) that needs to be completed, they also require the tax preparer to answer additional questions from the taxpayer and to track down their 12/31 IRA balances for the pro rata calculation using the IRA aggregation rule to determine exactly how much of the conversion was or wasn’t taxable, which often involves sifting through past account statements, as these balances are not reported anywhere else on the tax return.

And by respecting the CPA’s time, advisors can catapult themselves to the top of the industry in the minds of the tax professionals they reach out to (and it could even open the door for a lucrative stream of referrals)!

Anything Else I Should Know About Backdoor Roth Conversions?

Anytime we are talking about IRAs, Roths, contributions, and/or conversions, we need to revisit both the 5-year rule that applies to Roth conversions (which serves to determine whether the principal of amounts converted to Roth can be considered penalty-free), and the 5-year rule that applies to Roth contributions (which serves to determine whether a withdrawal of growth from a Roth IRA would be considered a tax-free 'qualified' distribution, and for which separate rules exist for Roth accounts under employer retirement plans).

Our go-to reference is this past blog article about Understanding the Two 5-Year Rules For Roth IRA Contributions And Conversions, but here is a quick refresher, courtesy of Micah Shilanski:

Any distributions taken from a qualified account are characterized in the following order: first from Contributions, then from Conversions, and lastly from Growth.

The 1st 5-year Rule (for Roth conversion principal) says that account owners under age 59.5 must wait 5 years before they can withdraw the principal of a prior Roth conversion without penalty (ignoring any other qualifying event). Once the client reaches age 59.5, this 5-year rule is no longer an issue.

The 2nd 5-year rule (for Roth growth of any type) says that any Growth on a Roth (from contributions or converted amounts) cannot be withdrawn without penalty until they have had any Roth account open for at least 5 years (and they must be over age 59 ½, or deceased or disabled, or using the money under the first-time homebuyer exception).

Example 4: Jane and Jim's financial advisor has determined that they are good candidates for using the backdoor Roth strategy.

Jane is 50 years old and never before has she opened an IRA account. Jim is 57 years old and has had a Roth IRA open for 15 years.

Their advisor establishes new Traditional IRA accounts for each of them, and a new Roth IRA account for Jane (as Jim already has one). After having each of them deposit $6,500 into their new Traditional IRA accounts, he successfully facilitates backdoor Roth conversions of $6,500 for each of them.

The prior contributions that Jim has put into his Roth IRA can be withdrawn at any time free of taxes or penalties, but the new Roth conversions they put into their respective Roth accounts this year cannot be withdrawn for 5 years (in the case of Jane) or for 2.5 years in the case of Jim (as once he reaches 59 ½, there is no early withdrawal penalty and the rest of that 5-year rule is moot).

When it comes to the growth of the accounts, Jane will be obligated to wait until she reaches age 59 ½ to access those amounts tax-free (as that is the later of 5 years and age 59 ½). In Jim’s case, because he has already had a Roth IRA in place for more than 5 years (already satisfying that rule), he will be able to access the growth tax-free in 2.5 years when he reaches age 59 ½.

In the event that Jane or Jim becomes disabled or passes away, the growth in Jim’s Roth would immediately be tax-free (since his 5-year rule was already satisfied) but Jane (or her beneficiaries) would have to wait out the remainder of the 5-year rule to access the growth tax-free.

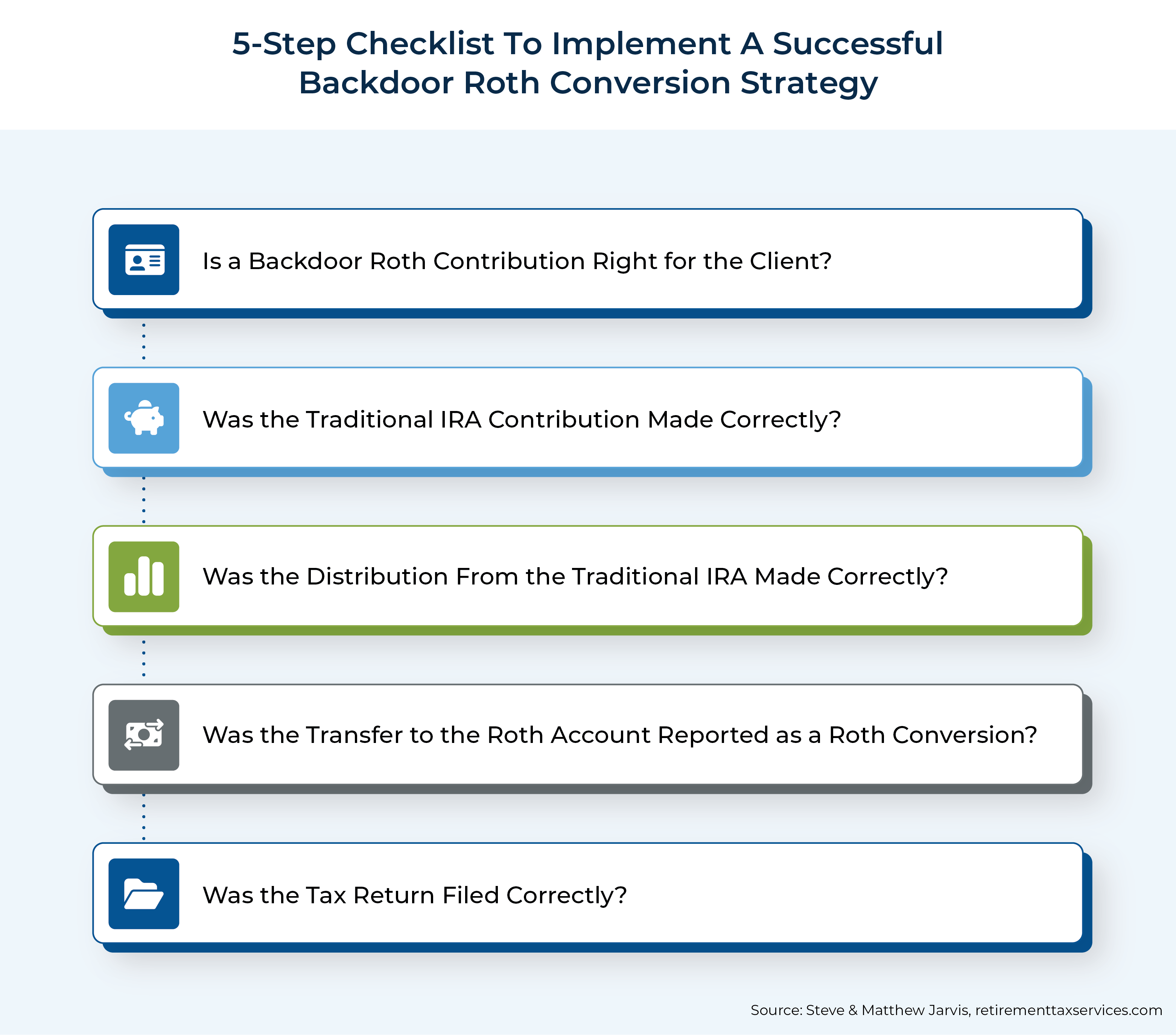

So Now What? A 5-Step Checklist

While there are many potential pitfalls, this 5-step checklist, which ideally would be built into an advisor's CRM system, will greatly enhance the advisor's ability to implement this strategy successfully and efficiently.

#1 – Is A Backdoor Roth Contribution Right For The Client?

Does the client have sufficient earned income to cover the IRA contribution (and too much to disqualify them from making a Roth IRA contribution directly)? Have all IRA balances (including those in SIMPLE and SEP accounts) been accounted for? Has the timing of any potential rollovers and prior IRA basis been considered? If the client does not have a 'clean' situation, is there a strategy in place for separating the proverbial tax-free cream from the tax-deferred coffee in the future?

If yes to all of these, a backdoor Roth conversion can be a practical and beneficial strategy to recommend to the client.

Mr. Client, one of our jobs as your Advicer is to make sure you are only paying the IRS what you legally owe but never leaving them a tip.

As part of this responsibility, our team is going to implement a backdoor Roth contribution, which, if done long enough, will potentially create a 6-figure bucket of tax-free money.

#2 – Was The Traditional IRA Contribution(s) Done Correctly?

Was a Traditional IRA contribution made in the current or prior year? Can the client make a catch-up contribution? Where are the funds coming from? Was the tax preparer consulted/advised, and do they know to report this as non-deductible?

For a conventional backdoor Roth contribution, this step includes verifying the funds were contributed to a qualified account and that no deduction was reported on the client’s 1040 for the year (if a deduction was taken it would appear on line 10 of the 1040 and schedule 1).

#3 – Was The Conversion Distribution From The Traditional IRA Reported Correctly?

While custodians typically do the distribution and conversion on a single form, it is reported to the IRS as a distribution from the IRA and a Conversion/Contribution into the Roth. The form 1099-R that is issued for the distribution will inevitably be marked as “taxable amount not determined” and will likely include the full amount as a “taxable distribution” on the form. Communication is key to ensure this is correctly reported on Form 1040 in spite of the 1099-R being potentially misleading.

While frustrating that the reporting is not more clear, this is the reality of how the system currently works. There is no need to contact the custodian or try to amend or adjust the 1099-R. The “taxable amount not determined” box tells the IRS that there is more to consider, so as long as Form 1040 is correct, the seeming contradiction between the tax return and 1099-R will not create an issue.

#4 – Was The Transfer To The Roth Account Reported As A Roth Conversion?

This move will need to be reflected on both IRS Form 1040 and Form 8606 (see examples included in this article). The tax-free benefits are not fully recognized until the conversion is completed and the funds are moved into a Roth account.

While contributions are reported in Part 1 of Form 8606, conversions are reported in Part 2 and are commonly left out by tax preparers. While not completing Part 2 of Form 8606 likely will not affect how much tax is paid in the year of the conversion, the form serves as a useful paper trail if questions come up in the future about conversions and contributions made into a taxpayer's Roth account (especially if the client needs to take out Roth conversion principal before age 59 ½ and then has to document that the 5-year rule on Roth conversion principal has been satisfied).

#5 – Was The Tax Return Filed Correctly?

This often requires reminding the client and tax preparer in January and then personally reviewing the return, including Form 8606, for accuracy once filed. Every planning recommendation that involves money has a tax impact of some kind. One of the best ways an advisor can impact a client having a successful tax return filed is to prepare an annual letter summarizing the tax impacts of the work they helped their client with during the year.

For this to be effective, there needs to be a system for accurately preparing the letter and communicating the results of the year to the client in a way they can easily share it with their tax professional. Until a tax planning strategy has been reported to the IRS correctly, it is not complete.

If this all sounds complicated and labor-intensive, take a step back to remind yourself that strategies like these can be beneficial and well worth the effort they require to implement; taking the time to understand them and making the effort to explain how and why things work to clients (and their tax preparers) is exactly what differentiates a Financial Advicer from a financial advisor.

It's also what sets advicers apart from all of the firms who won't touch anything tax-related and gives them an advantage when attempting to demonstrate to prospective clients why their firm is the best fit for their needs.