Executive Summary

Welcome to the January 2024 issue of the Latest News in Financial #AdvisorTech – where we look at the big news, announcements, and underlying trends and developments that are emerging in the world of technology solutions for financial advisors!

This month's edition kicks off with the news that held-away asset management platform Pontera has raised $60 million in venture capital funding as advisors increasingly seek to directly manage clients' 401(k) and other outside assets – although claims by Washington state regulators that advisors' use of Pontera may violate state regulations on accessing data with client passwords, and/or employer retirement plans' terms of service, raises questions over whether Pontera (and the advisors who use it) can convince regulators that its underlying model doesn't violate client privacy.

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

- JPMorgan has announced plans to shut down its robo-advisor offering after just four years, highlighting broadly the challenges of robo-advisors to overcome the challenging economics of acquiring and serving small clients, and in particular showing that even a company like JPMorgan with a large customer base can struggle to distribute its offerings when those offerings don't match the needs or wants of its (largely banking-focused) customers

- Envestnet is rumored to be exploring a sale of account aggregation provider Yodlee, which highlights the struggles that account aggregation has had in living up to its original promise to provide holistic insights into client data – in large part because it has been such a challenge to maintain the integrity of the data itself, leaving little capacity to figure out how to convert that data into meaningful insights for advisors

- Income Lab has announced that it has chosen BridgeFT to provide it with API access to multi-custodian data for its retirement planning software, signaling more broadly the need for API hubs that can allow technology startups to access custodial data without the cumbersome process of building and maintaining connections with individual custodians – a need that BridgeFT has risen to fill with its WealthTech API solution.

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

- Arch, a technology provider aiming to streamline the significant administrative and paperwork burden of managing multiple alternative investments, has completed a $20 million Series A funding round as advisors' interest in alternatives continues to grow (though it remains to be seen if investor interest in alternatives will stay as high in a higher interest rate environment)

- The SEC has been soliciting feedback from RIAs on their use of AI technology as it seeks to finalize its proposed "Predictive Data Analytics" rule, which has been widely criticized as imposing an onerous compliance burden on firms surrounding the technology they use (even if that technology has little to do with AI to begin with)

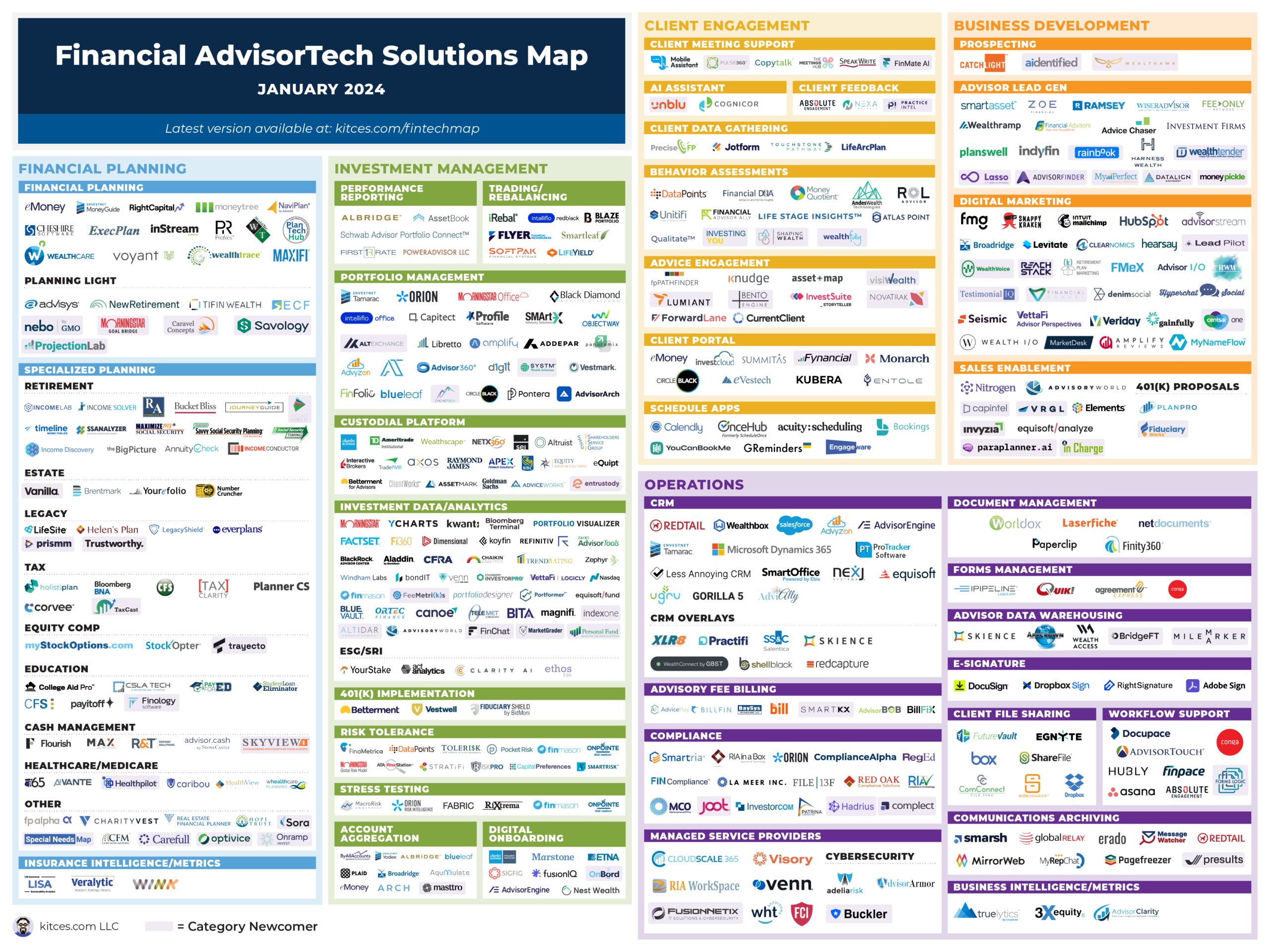

And be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular "Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map" (and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory) as well!

*And for #AdvisorTech companies who want to submit their tech announcements for consideration in future issues, please submit to [email protected]!

Pontera Raises $60M Amid Growing Demand For Managing Clients' Held-Away Assets (While Washington State Regulators Crack Down On Its Use)

Traditionally, doing business under the Assets Under Management (AUM) model was predicated on the advisor directly managing the client's assets. For regulatory purposes, advisors can't claim a client's assets within their AUM unless they provide "continuous and regular" services within the client's accounts, which in practice involves actually implementing trading recommendations on behalf of the client – if the advisor simply advises the client to make a trade, and the client places the order on their own, it doesn't meet the management part of assets under management.

Of course, advisors can still provide investment advice to their clients for accounts where the advisor doesn't place the trades themselves, and even bill on an Assets Under Advisement (AUA) basis for those accounts, but practically speaking there has always been a difference in the way advisors priced AUM fees on directly managed accounts and AUA fees on "advised" accounts, reflecting the different levels of service involved for actually managing assets in an account versus 'just' providing advice for the client to implement on their own. And so even as the AUA model has grown in popularity over the past decade – as account aggregation tools have made it easier to monitor and bill on household accounts, while the predominant investing strategy has migrated towards a "Buy and Hold and Monitor" model where trades are made mostly for rebalancing purposes only, necessitating fewer trade recommendations for the client to implement – there have remained hurdles for advisors in adopting the model due to its two-tier fee structure as well as the challenge of effectively communicating trading instructions (and follow-up reminders) to clients. But despite the challenges, the AUA model can be appealing to advisors as an opportunity to advise on a greater share of assets for existing clients, as well as to be able to serve new clients who may not have been able to work with the advisor under an AUM-only model (e.g., clients whose investable assets were mainly sequestered in their 401(k) plans).

In 2018, Pontera (then known as FeeX) emerged with a solution for advisors to overcome the operational hurdles of managing held-away accounts. Having originated as a retail-focused solution to help 401(k) plan participants understand the fees layered into their retirement accounts, FeeX had pivoted to offering its technology to advisors to help them implement trades within clients' 401(k) plans. Which effectively made it a tool for converting a client's advised assets into assets that were actually managed directly by the advisor, allowing the advisor to provide the same level of "continuous and regular" service over a client's held-away accounts as those held on the advisor's custodial platform and justify charging the same level of fees across all of the client's assets, while also eliminating the hassle that comes with recommending trades to clients and the subsequent need to follow up and ensure that they were actually implemented.

Against this background, Pontera is in the news after raising $60 million in venture capital funding, the latest in a successive series of funding rounds since it made its pivot into facilitating the management of held-away assets. Notably, of the nearly $160 million of total funding Pontera/FeeX has received since its founding in 2012, over $130 million has come since 2021, signifying a high pace of adoption among advisors and, more broadly, a reflection of the growing desire of advisors to expand their AUM to include clients' held-away assets.

Ironically, at the same time Pontera has raised funds to expand and scale its offering, it is also facing a challenge from regulators in the state of Washington, who have recently made a surprising claim that an advisor's use of Pontera may constitute a breach of Washington's administrative code by directing clients to provide their 401(k) plan login information to the platform (even though that information isn't shared with the advisors themselves), as well as whether the client's providing login information to a third-party is a violation of their 401(k) plans' terms of service. And although no other states have raised similar concerns about Pontera as of yet, Washington's administrative code aligns with NASAA's Model Rule on Unethical Business Practices of Investment Advisers, raising questions about whether other states that also use the Model Rule will take notice and launch their own inquiries, which could put a significant damper on Pontera's growth plans unless it is able to address regulators' issues and/or convince them that their concerns are unfounded.

Still, in spite of the regulatory questions hanging over it, Pontera's fundraising success in what has been a challenging year for venture capital funding in the AdvisorTech landscape highlights the ongoing demand for access to clients' held-away assets. Going forward, however, the biggest questions will be: (1) whether regulators will continue to raise flags over advisors trading directly in clients' 401(k) accounts via third-party platforms like Pontera, despite both advisors and clients seeming to be happy with the arrangement; and (2) whether Pontera's run of success in both client growth and fundraising will spawn new competitors (which have so far been few and far between in the held-away asset management niche), creating headwinds for solutions like Pontera for increasing management over more and more of clients' balance sheets.

JPMorgan Shuts Down Its Robo-Advisor As Asset Management Distribution Remains A Distribution (Not "Robo" Automation) Challenge

Robo-advisors launched in the early 2010s on the presumption that investment management could be done so cheaply through the use of digital onboarding and automated trading and rebalancing technology that robo-advisors could charge just 25bps to manage customers' investments, which would in turn cause consumers to flock to robo-advisor solutions for the cost savings over paying 100bps to a “traditional” human financial advisor. Put more simply, the early robo-advisors' business model was "If you build it, they will come", and with this story in hand robo-advisors raised hundreds of millions of dollars in funding to unlock the market potential they expected their technology to bring.

The caveat – as independent advisors have long known – is that the main cost driver in providing financial advice isn't the actual time it takes to construct a diversified portfolio and implement it, but rather how challenging it is to acquire a large volume of new clients, in terms of both hard-dollar marketing costs as well as in the advisor's time to market and grow their business. And compared with investment management, client acquisition costs are much more difficult to scale using technology – hence why so many advisors have been so willing to pay fully 25% of revenue for clients referred by various lead generation services, which themselves have had struggles with their own acquisition costs for supplying a steadily growing flow of quality prospects to refer to advisors. And with the costs of acquisition so high, clients need to generate sufficient revenue over a long enough period of time in order to be profitable for the advisor in the long run, making "small" clients an exceptional challenge due to the simple economics of the cost of bringing them on as a client versus the amount of revenue they provide.

The result of these economics was that many direct-to-consumer robo-advisors burned through cash and ultimately failed as it proved impossible for them to achieve the growth rates needed stay afloat with negative economics on each client. The survivors of this initial fallout generally fell into two categories: Firms like Betterment or Wealthfront that had initially raised the most capital for client acquisition and were able to achieve at least a critical mass of assets for sustainability (if not fulfilling the ambitious initial growth plans of their founders); and established asset management firms that could cross-sell digital advice solutions (such as Vanguard's Digital Advisor and Charles Schwab's Intelligent Portfolios) to their existing mutual fund and ETF investors without the need to accumulate an entire user base from scratch. Notably, these firms could also populate the investment models of their robo-advisor solutions with their own funds – and in fact already had a base of clientele to cross-sell to because they were already in the business of building and selling their own investment products – allowing them to earn fees on both the robo-advisors themselves, and their underlying funds, to squeeze more profitability out of the otherwise-marginal robo-advisor model (or in Schwab's case, to also earn a spread on the interest paid on their cash sweep account with their mandatory-cash client allocations).

The success of large institutional firms like Vanguard and Schwab experienced with offering robo-advisors attracted other large companies to enter the fray. In the late 2010s, new robo-advisors appeared from Morgan Stanley (2017), Merrill Lynch (2017), Wells Fargo (2017), and JPMorgan (2019). This new group differed from its predecessors, however, in that they charged higher fees of 35 – 50 bps instead of 25 bps (as the challenging economics of earlier, lower-cost robo-advisors were already becoming apparent at the time), as well as being more overt about their intent to not just offer investment services to smaller clients, per se, but to use their robo-advisor services as a distribution channel for their proprietary investment products in order to expand their "wallet share" of their existing customers.

But in a signal that the "robo-advisor-as-fund-distribution-channel" model isn’t any less challenging and cutthroat than any asset management distribution channel, JPMorgan recently announced that it is shutting down its robo-advisor after just four years, citing the lack of profitability of charging "just" 35bps to grow the user base for its digitally-managed portfolio of proprietary ETFs. Which serves as a tacit acknowledgement that even with an existing customer base, the economics of client acquisition remain a challenge, particularly when seeking to reach small investors (which JPMorgan did with an investment minimum of only $2,500 for its robo-advisor). Although what also likely contributed to JPMorgan's struggles was that it is primarily a bank, with its customers holding checking and savings accounts, mortgages, and other banking products… such that part of the challenge may have been that it was harder than imagined to cross-sell investment solutions to banking clients (as opposed to customers of Vanguard and Schwab, who by definition already owned investments with those firms, and could therefore be assumed to be at least reasonably likely to be in the market for another investment solution from what was already their investment provider of choice).

From an industry perspective, the rise and fall of JPMorgan’s robo-advisor highlights the reality that asset management – whether for investment vehicles like ETFs or mutual funds, or for advisors who allocate them in portfolios – remains first and foremost a distribution challenge. Just as offering a robo-advice solution as an advisor won’t automatically cause consumers to flock to sign up, wrapping a robo-advisor label around a proprietary fund offering doesn’t change the challenge that at the end of the day, it’s the customer who gets to decide who to delegate authority to manage their assets: They need first to know that it exists, and then to like what they see enough to sign up, which simply isn’t going to be accomplished by putting a “Sign Up Here” button on the corner of the website and waiting for the assets to roll in. And for all the advantages of having an existing customer base, if the product being cross-sold to them isn’t something they want or expect from the firm, it may be no more efficient to attract users from the existing customer base than it is to draw in a whole new customer base from scratch.

In the end, then, while robo-advisor tools can serve to automate internal efficiencies and reduce the overhead required to provide asset management, the last decade has shown that they're really only profitable for those with the strongest distribution channels for their asset management to begin with – which was true before robo-advisors came along, and will remain true as the current generation muddles along or fades away over time.

Envestnet Exploring A Sale Of Yodlee After Struggling To Turn Data Aggregation Into Meaningful Advisor Insights

Nearly 15 years ago, Mint.com first showed the promise that the Internet held for personal financial management, by allowing users to connect all of their bank, investment, credit card, and other financial accounts to a single portal, which was updated in real time to provide balance sheets and spending summaries (in a fraction of the time it took to manually track on paper, or by updating a static spreadsheet). Mint's revelation led to a frenzy of companies seeking to leverage account aggregation for their own purposes, which required them to figure out (1) how to best access the data; (2) how to arrange and display it; and most importantly, (3) what to actually do with the data that led to meaningful insights (and actionable outcomes that consumers or businesses would actually pay for). Because after all, the value of software like Mint wasn't (just) in the fun of seeing all of one's financial life onscreen; it was about using that information to make better decisions on spending, saving, and investing.

Eventually, the main use cases for data aggregation diverged into two channels. First there were the direct-to-consumer tools, typified by Mint and later competitors like YNAB and Monarch Money, which were used by consumers themselves to manage their own financial household, and which were monetized by their providers either by using affiliate offer arrangements that took advantage of customer data to recommend products such as savings accounts and credit cards (which was Mint's business model), or by simply charging fees directly to users (as YNAB and Monarch do). In this channel, the direct-fee model appears to be winning out, as Mint struggled to generate enough uptake for its affiliate offers to remain profitable on its own and now is being merged away into (larger affiliate platform) Credit Karma.

The other data aggregation channel was more institutional, and provided account data to businesses to be used for business purposes. On a micro level, financial advisors could use data aggregation on behalf of their clients for similar purposes as Mint and its ilk, to gather client information in order to provide a client financial dashboard (as first eMoney and then other planning software adopted), to facilitate financial plan updates using automatically-updated account balances (as MoneyGuide Pro did in some of its early integrations with custodians and investment management platforms), or for use in advising clients on their held-away assets under an Assets Under Advisement model (as aggregation providers like ByAllAccounts integrated with portfolio management platforms like Orion). But more tantalizing was the promise of account aggregation on a bigger scale, to provide big-data analysis across many households that could generate insights on how advisors could best offer, market, and price their services (and how product manufacturers could best get in front of the right advisors and their best-fit clientele).

The data aggregation era seemed to reach a watershed moment in 2015 when Envestnet bought account aggregation provider Yodlee (which handled account aggregation for Mint, eMoney, RightCapital, and many other platforms) for a whopping $590 million. The vision at the time was of creating a unified view of the client's entire household, with all of the insights that a holistic view can provide in giving advice to individual clients – as well as insights on the advisor's client base in the aggregate.

In the news recently, however, are reports that Envestnet is exploring the sale of Yodlee, and has hired an investment banker to help advise them on their options. The news comes as Envestnet remains beleaguered by activist shareholders concerned with slow growth and difficulty in monetizing its acquisition of the data aggregation platform. Notably, there were also rumors of a pending Yodlee sale back in early 2020, which ultimately faded amid the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, the situation for Yodlee hasn't improved in the intervening years. Although there is no reported asking price yet, analysts have suggested that Envestnet could receive as little as half of the original $590 million purchase price, owing both to planned regulatory crackdowns on its use of "screen-scraping" technology to gather client data (which was also recently banned by Fidelity), and to the erosion of its market share by competitors like Plaid (as well as direct API access to custodial accounts that can eliminate the need for a standalone aggregation platform altogether).

From an advisor perspective, Envestnet's sale of Yodlee isn't likely to change much in terms of day-to-day functionality of their data aggregation tools for those who do use Yodlee to power underlying data flows. Yodlee will, in all likelihood, stick around in some form or another, and even if Envestnet sells Yodlee, it could continue to license its data for tools like MoneyGuide (which Envestnet also owns). And between Plaid and other direct data feed technology, AdvisorTech providers have multiple other options for facilitating data aggregation capabilities to ensure continuity of data for advisors and their clients.

From an industry perspective, however, the story of Envestnet's ownership of Yodlee is a sad encapsulation of the ways in which the reality of account aggregation has struggled to live up to its initial promise and potential. While in theory the appeal of account aggregation is in the insights that come from observing data trends – both big and small – over time, actually turning big data into relevant insights that advisors can use for advice has proven to be much harder in practice. Which may be at least partially a function of the instability that has always been endemic to data aggregation platforms in the first place, with breakages of data links proving a frequent occurrence as client passwords change and financial institutions update their security measures, meaning that much of the software development and engineering efforts that could have gone to providing better answers to the question of what to do with the data instead went to maintaining and improving the stability of the data itself.

In the end, what's happened with Yodlee doesn't necessarily mean that there isn't a future for data aggregation among advisors. However, despite the promise of the opportunities of "big data" that have been proclaimed since the aughts, in the end it comes down to who has an actual plan for what to do with the data, that meaningfully improves advisor value and advice outcomes for clients, instead of focusing on the data first and figuring out what to do with it later on.

Income Lab Selects BridgeFT's Wealthtech API To Aggregate Multi-Custodial Data

Most technology used by advisors today is connected in some way or another to the portfolio that the advisor is managing on the client's behalf: Alongside the actual portfolio management software itself that handles trading and rebalancing, there are platforms like performance reporting software that calculate performance based on daily balances and cash flows; billing software that calculates the advisor's ongoing fees and generates billing files to send to custodians; and financial planning software that turns today's portfolio balance and asset allocation into projections of future scenarios. But in order for any of this software to run efficiently, it needs to have access to automatically-updating data on the client's portfolio.

At this point, all of the major RIA custodial platforms have built some version of an API that software providers can integrate with for access to the data that they need. But there's a catch: There's no single set of standards used across all custodians for providing access to client data; rather, each one has its own formats and data standards, and perhaps most challengingly, each custodian has what can often be a lengthy due diligence process that a software provider must complete before being granted access to the custodian's API. Multiplied across dozens of custodial platforms, the result is that trying to connect to each custodian individually would cause new technology vendors to endure a long wait in due diligence purgatory before they can start to integrate the client data that makes their products work – a time during which they essentially can't sell their product and start generating revenue, requiring cash infusions from the company's founders and/or outside investors to keep paying its employees until the product can actually be sold.

To streamline the process of integrating with custodial data, software startups have tended to migrate towards data "hubs", which can provide access to data from multiple sources, and which save valuable time for the software provider by only requiring a single point of connection (and thus a single due diligence process) while giving access to multiple data sources at once. In practice, these hubs tended to be platforms from which advisors ran much of their practices: Portfolio management system platforms (e.g., Orion, Black Diamond, or Tamarac) which already pulled in custodial data themselves and could thus serve as a useful connection point for a third-party vendor to tie into like running a new electrical line from an existing outlet on the wall; as well as some of the most-used custodians themselves, e.g., TDAmeritrade and its Veo platform, which long had a reputation of being a hub that was easy to integrate with as a software provider.

In more recent years, however, some of the most popular data connection hubs have lost their utility to software providers. As large portfolio management platforms have become increasingly "all-in-one" with their own self-integrating software suites, many of those platforms now have their own solutions that compete directly with outside software, making it less appealing for those vendors to build and promote integrations with an all-in-one platform that aims to ultimately make them redundant. And following TDAmeritrade's acquisition by Charles Schwab, the Veo platform ceased to exist and data vendors were migrated into Schwab's Advisor Center, which has a lengthier process (and therefore a longer waiting list) for new integration partners than its predecessor at TDAmeritrade. And so for technology providers, there has been an increasing need for new sources of custodial data, as the old channels have become less reliable and the cumbersome process of building and maintaining point-to-point connections with each individual custodian remains as daunting as ever.

In that vein, it's notable that retirement planning software startup Income Lab recently announced an integration with BridgeFT that will facilitate access to major custodian and broker-dealer platforms through BridgeFT's WealthTech API hub. BridgeFT's roots were as a portfolio accounting and performance reporting solution in competition with the higher-priced Orion, Black Diamand, and Tamarac all-in-one platforms, for which it needed to build its own data feeds with custodians and convert the multiple streams of data into a single standardized format. Which as BridgeFT eventually discovered was, when provided to other software tools, a value proposition in and of itself – and perhaps represented a greater opportunity than being one of 50 different competing portfolio management solutions on the market.

And so in providing multi-custodian data access to other software providers, BridgeFT is stepping in to fill the void left by the loss of Veo as well as by the increasingly "walled-garden" approach of the biggest portfolio management platforms. Which perhaps has its biggest impact for newer technology firms in their startup phase: Rather than building their own integrations to all of the individual custodial platforms, a new technology company can simply buy access to BridgeFT's feed, with BridgeFT handling the work of maintaining the connections and standardizing different data formats. Which ultimately can serve to greatly expedite how quickly the new software provider can get access to custodial data (since it no longer needs to go through a separate due diligence process for each custodial platform before accessing its data), while also drastically reducing the work needed to maintain those connections (and allowing developers and engineers to focus on building and refining the software itself, rather than sinking time and energy into simply ensuring a reliable data feed).

From BridgeFT's perspective, then, the announcement seems to show that the company is positioned well for growth from its data integration business: as more and more technology vendors come into the market to serve advisors, the demand for access custodial data doesn't seem likely to slow down anytime soon.

From the industry perspective, the question is whether BridgeFT can effectively fill the void as the go-to API "hub" for new technology startups looking to quickly get access to custodial data. Which would obviously be good for its own business model, but more broadly, could also increase the pace of innovation in the AdvisorTech space at large, by eliminating many of the roadblocks that new technology firms face in connecting to multi-custodian data and consequently reducing the time and startup capital needed to get new software products to market.

Arch Raises $20M To Simplify The Administration Of Alternative Investments

The roots of today's financial advisors were in helping clients to invest in traditional stocks and bonds. Originally, most financial advisors worked for broker-dealers who dealt primarily or exclusively in publicly traded securities, and although the types of vehicles that advisors have used to implement their recommendations have evolved and expanded over time – from directly held securities to mutual funds and ETFs to SMAs and UMAs – the underlying assets that advisors recommended for investment were almost always stocks and bonds that traded on public exchanges.

In the years since the 2008 financial crisis, however, several broad market trends have led more advisors to consider alternatives to the traditional stocks-and-bonds allocation models. First, an increase in the number of startups deciding to remain private rather than go public, combined with a steady pace of mergers and private takeovers of companies on the public market, has resulted in a drop in the number of publicly traded companies, with public markets representing a smaller slice of the overall economy than it once did, and has increased the appeal of private markets simply to stay exposed to leading companies that may have been public in an earlier era. Second, the rise of private equity – which itself fueled much of the economy's shift into private markets – has attracted attention from a broader swath of investors than its traditional institutional clientele, as individual investors are drawn to the to the outsized returns reported by private funds. And third, as interest rates dropped to near zero after the crisis and stayed there for much of the decade of the 2010s, publicly traded bonds – which were traditionally held by investors both for their role in dampening portfolio volatility as well as the interest income they produced – gained a reputation as more of a drag on portfolios than a diversifying element, leading investors to consider other options that could continue to diversify while also contributing something – at least more than the paltry bond yields at the time – to the portfolio's return.

And so with the increasing interest in private and alternative investments, there has been a concurrent rise in financial advisors looking to connect clients with assets like private equity, private debt, and real estate investments. And although advisors have traditionally had a direct role in connecting clients with private funds, in recent years there has also been an emergence of technology platforms, such as iCapital and CAIS, which aim to provide a marketplace for various categories of alternative investments for advisors to allocate their clients' funds into, which can serve to significantly reduce the time needed to research, connect with, and perform due diligence on prospective private fund managers.

But while it has become easier for advisors to help their clients invest in private markets, from an administrative standpoint holding private investments is much different from holding traditional stocks, bonds, and funds. Each private investment has its own structure in terms of its capital commitments, the timing of its capital calls, and the corporate actions of either the fund itself or its underlying companies, each of which requires communication with (and often timely action by) the investor. Additionally, owing to their typical limited partnership structure, private investments have their own unique tax reporting obligations that require keeping track of additional forms like K-1s. And there's no standard way of doing any of this: Funds still often send paper communications via snail mail, or at best as a PDF attachment to an email, which in both instances lends itself to being lost track of without a dedicated organization system. For an investor with a single private investment, this may all amount to "just" an inconvenience requiring a little extra administrative effort; however, for someone with 10 or more private investments – or even worse, for an advisory firm with an entire client base holding multiple private investments – the sheer amount of paperwork could quickly become an unmanageable administrative burden.

In this vein, it's notable that Arch, a technology company aiming to help streamline the administrative burden of handling alternative investments, has raised $20 million of venture capital funding in a recent Series A round. Investors in this round notably include Jason Wenk (founder of next-generation custodial platform Altruist), Steve Lockshin (founder of estate planning software platform Vanilla), and Marc Spilker and Scott Prince (co-founders of Merchant Investment Management, a private equity investor in financial services firms as well as a provider of its own alternative investment solutions).

The value proposition in Arch's technology seems to be in combining performance reporting on alternative investments – a challenge that other reporting tools like Addepar have also worked to solve for – with centralizing and streamlining the flow of paperwork, in the form of capital calls, distributions, communications on corporate actions, and tax forms, that comes along with alternative investments. The goal is to provide a single portal for all of an investor's private investments, automatically flagging capital calls and other action items, providing tax information for accountants, and maintaining a searchable archive of communications for each investment, ultimately eliminating the need to organize a mix of paper and PDF statements and juggle separate logins for different fund providers' portals.

To this end, Arch is clearly targeted at advisors for whom private investments present a real scalability challenge. For advisors whose clients might get one or two K-1 forms each year for private investments, there's limited value in consolidating everything in a single portal; but for advisors who use alternatives across their entire client base, a centralized platform could do much to solve the administrative hurdles of investing in alternatives.

From an industry perspective, the opportunities for Arch, along with its competitors such as Canoe and Masttro, have grown in tandem with the rise in interest in alternative assets. As market trends have driven investors to question whether the risk-adjusted returns of public markets alone are "good enough", the pressure has grown on advisors to explore alternatives, particularly in the fixed income side of the portfolio which has been both poor performing and more volatile than expected. Which ultimately raises the question of whether the return of higher interest rates – and subsequently higher yields on bonds – will affect advisors' appetites for alternative investments on the expectation that public markets will eventually revert to a more "normal" state. But at the same time, if tools like Arch can really make it materially easier to hold, track, report on, and manage private investments, to the extent that they aren't quite so much more burdensome to administer than traditional publicly traded securities, then maybe they can help alternatives increase their staying power even as investment trends shift further over time.

The SEC Is Questioning RIAs On Their Use Of AI In The Midst Of Advisor Pushback On Its Overly-Broad 'Predictive Data Analytics' (PDA) Rule

There are generally two use cases for financial advisors when it comes to Artificial Intelligence (AI). One is as a back- and middle-office support tool, which could support advisors through transcribing and summarizing meeting notes, reading and pulling key data from client documents, creating drafts of client emails for the advisor to touch up and send, etc. The second potential use case is more directly client-facing, and could involve analyzing everything from clients' balance sheets to their spending behaviors to market movements in order to recommend some kind of action (and then nudge or outright prompt clients to take action to implement it).

The first (back-office) case has gained popularity among many independent advisors because it can significantly streamline manual administrative tasks such as writing emails and reading through client documents, freeing up the advisor's and their staff's time for more valuable tasks. However, most independent advisors haven't dabbled as much in the second (client-facing) case, in part because fewer technology options for this case actually exist on the market today, but also because it feels significantly riskier. Advisors have a fiduciary duty to make recommendations in their clients' best interests, and that duty extends to any recommendations they give via technology – but if the technology making the recommendation is too inscrutable to understand what kind of analysis is going on underneath the hood, then there's no way for the advisor to even know whether the recommendation is in fact in the client's best interest (despite being legally accountable for that outcome). And with the black box nature of most AI technology, it's difficult to envision using it as way to actually formulate and give recommendations (setting aside the reliability of AI technology itself, which has also been shown to be prone to bias and even making up facts out of thin air).

Where the client-facing use case of AI has taken off, however, is among larger retail-oriented firms such as robo-advisors like Betterment and broker-dealers like Robinhood, which have access to reams of data from their huge customer bases and can develop models on which to train their own AI tools – allowing them to analyze customer data such as smartphone usage behavior to deliver recommendations that are optimized to result in a specific action (e.g., opening an account or trading in a certain stock). Which presents the potential for a conflict of interest: If an AI tool pushes out a recommendation to a customer, that recommendation might have a sheen of objectivity since it came from technology; however, if the AI itself is trained to prioritize products that are proprietary or otherwise trigger activity that generates the most revenue for the firm, it would clearly be misleading to pretend that it's simply making a neutral recommendation.

Recognizing the potential for misleading or manipulative practices via the use of client-facing AI technology, the SEC released a Proposed Rule in July that would require investment advisers and broker-dealers using any type of "Predictive Data Analytics" (PDA) or PDA-like technology in interactions with investors to eliminate or neutralize any conflicts of interest associated with their use of those technologies. The proposed rule continues a common thread of the SEC under its current chair Gary Gensler of scrutinizing what it sees as manipulative "Digital Engagement Practices" by financial institutions (e.g., its earlier probe into "gamification" tactics by Robinhood and others to encourage trading on their platforms), but adds a twist by including whole categories of technology that would be covered by the rule, rather than simply focusing on the practices of financial firms themselves. Additionally, the proposed requirement to actually eliminate or neutralize conflicts of interest, rather than "just" disclose them to clients, signifies how serious the SEC believes the issue of AI-related conflicts to be.

The issue with the SEC's proposed rule, however, is that it is so broad in its definition of what constitutes a "covered technology" that it would include nearly every type of technology used by an advisor to make recommendations, including many that would stretch the definition of what is considered AI. The proposed rules define covered technology as an "analytical, technological, or computational function, algorithm, model, correlation matrix, or similar method or process that optimizes for, predicts, guides, forecasts, or directs investment-related behaviors or outcomes". Which could theoretically include anything from rebalancing software (which calculates optimal trades) to risk tolerance tools (which guides investment-related decisions) to financial planning software (which advisors use to forecast and make investment-related recommendations to achieve desired outcomes). In other words, if anything that uses a "computational function" to "predict" or "guide" investment-related behaviors, then anything related to financial planning – which by its nature is literally all about predicting and guiding future financial behaviors – could be covered by the rule, and thus require advisors to scrutinize for and eliminate any conflicts of interest. For which it’s not enough to simply be without a conflict of interest as a fiduciary advisor; the burden of proof would be on the advisor to show that they had established and followed policies and procedures to comply with the rule, which at best adds to an advisory firm’s administrative compliance burdens (even if just to prove what it is already doing well).

And so there has naturally been pushback from industry groups such as the Investment Adviser Association, as well as from individual advisors and CCOs, who fear that the hurdles of vetting all of a firm's technology under the SEC’s new framework will make compliance all but impossible (especially given that so much of an advisor's technology comes from third party vendors, meaning the advisor may have little ability to fully scrutinize, let alone make changes to, the technology to comply with the rule).

It's notable, then, that the SEC has been taking steps to solicit information that could lead to a modification of the proposed rule. As reported this month, the SEC has sent letters to a number of RIAs requesting details on their use of AI technology, including algorithmic portfolio management, the use of third-party software providers, as well as firms' marketing materials that mention their use of AI. Additionally, the SEC's own Investor Advisory Committee has raised concerns about the scope of the proposed rule, sending a letter to the SEC expressing its concern about the rule imposing "many rigorous prescriptive requirements on an overly broad swath of technologies" and asking the commission to narrow the rule's scope to use more narrowly targeted definitions of PDA and AI technology.

From an advisor perspective, while there are a lot of questions about what shape the SEC's final rule around PDA technology will take, it seems at least possible that it won't be as wide-ranging as the proposed version, and could perhaps include some carveouts for third-party technology that could reduce the compliance burden for smaller firms. While from a broader industry perspective, it's clear that the current leadership of the SEC is very interested in scrutinizing how financial firms use client data to generate recommendations, and in particular those that use predictive data to influence customer decisions that can ultimately generate revenue for the firm. Although notably, given that the SEC's leaders are appointed (and their regulatory agendas are largely set) by the sitting president, the results of next fall's election is likely to have a sizeable impact on what version (if any) of the proposed AI rule the SEC will ultimately go forward with. In the meantime, however, it appears that while AI tools may be generally fair game for advisors to use for back-office purposes, advisors may need to prepare to more fully scrutinize all of their technology that goes into making client recommendations – even those that wouldn't normally be considered "AI" in the first place.

In the meantime, we've rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map (produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group)!

So what do you think? Does advising on clients' held-away assets make more sense with a technology like Pontera to manage them directly? Do alternative investments represent enough of a paperwork burden that using a solution like Arch to centralize it all would create meaningful time savings? How would your firm be impacted if you were required to scrutinize and eliminate any conflicts of interest in software covered by the SEC's proposed AI rule? Let us know your thoughts by sharing in the comments below!