Executive Summary

The need for financial professionals to ask prospects and clients questions has a long history in the industry. In earlier days, questions simply facilitated the process of gathering information in order to open accounts and recommend the appropriate products to be sold. However, as the industry evolved from being primarily transaction-based to relationship-based, it has become increasingly important for advicers to become less sales-oriented and more focused on how they can better develop deep, long-term connections with their clients. One of the best ways to accomplish that goal is not to ask better questions, but to also ask engaging follow-up questions that build trust and rapport with clients. The key, then, is in learning a conversational skillset that is natural and keeps the focus on the client.

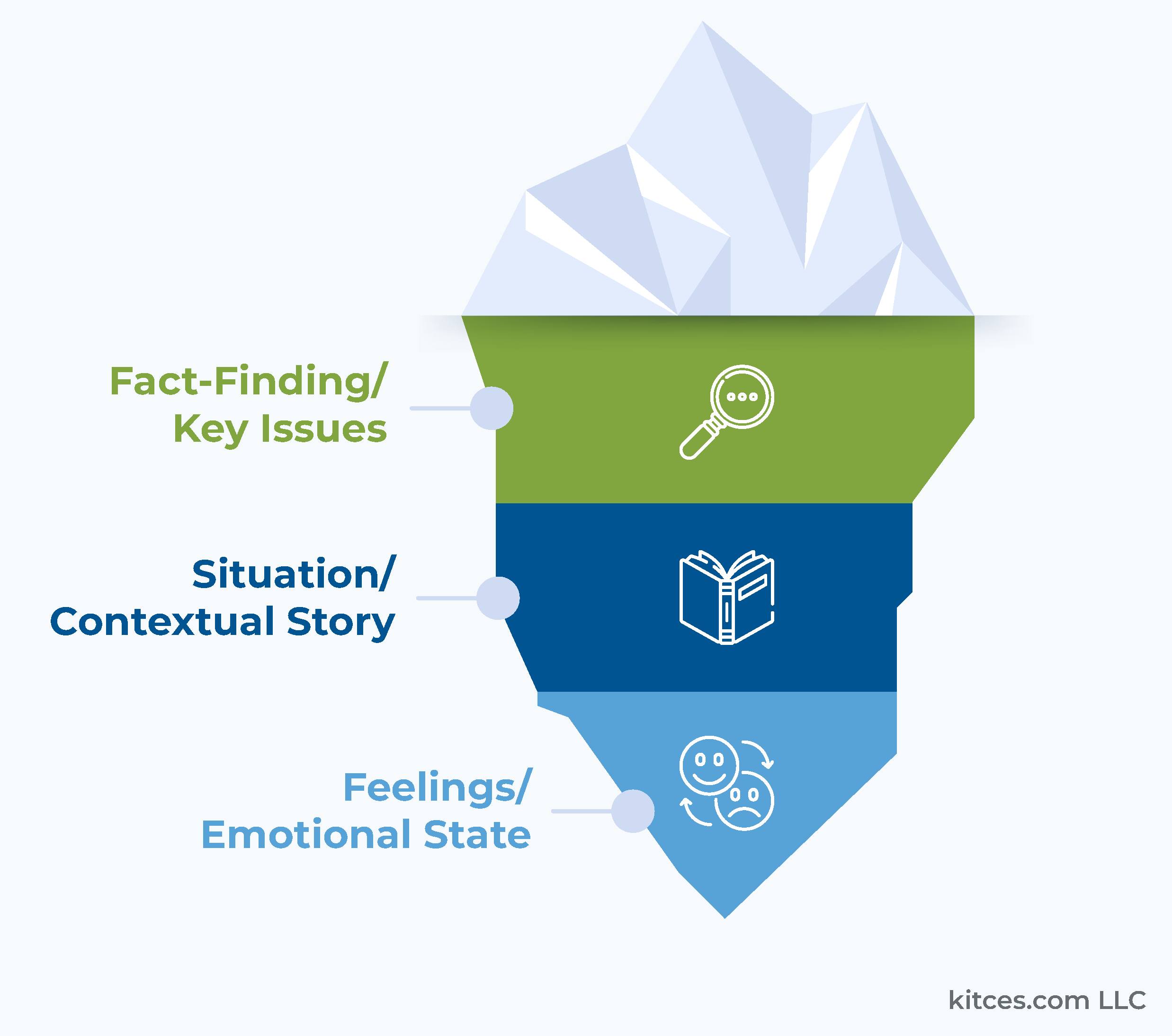

Fortunately, there is framework that advicers can use to ask authentic and impactful follow-up questions called the Iceberg Method. This technique utilizes a 3-question format that uncovers what matters most to a client and helps develop (and deepen) the client/advicer relationship. It features a succession of questions that first seeks to uncover key facts, then explores the meaning and situational context around those facts, and, finally, offers insight into the client's feelings and values around their particular situation.

Accordingly, the process starts with fact-finding questions, which ideally should be open-ended questions framed as statements (e.g., telling the client or prospect to share what prompted them to reach out), since people can sometimes perceive fact-finding questions such as "What have you done so far to save for retirement?" as judgmental. From there, advicers can dig deeper into the iceberg by asking follow-up questions that are designed to discover the context around information gleaned from the fact-finding stage. These 'situation' questions (which, again, are also more effective when presented in the command/statement form) help the client tell the story around their facts and share why something is important to them.

After understanding the facts and gaining additional situational context, advicers can finally explore the feelings that the client has around the subject that's under discussion by asking follow-up questions about their emotions. Framing these questions properly is essential. Introducing these questions with phrases such as, "It seems that," or, "I've noticed that" or "I'm interested in hearing more about" and then asking how they feel about the accompanying observations is an effective way to invite clients to reveal their honest feelings that drive and inspire them to commit to their financial goals (and implement their advicer's recommendations!).

Ultimately, the key point is that advicers who can learn how to communicate more effectively will not only differentiate themselves in the marketplace, but (importantly) will also do a better job of helping their clients achieve their goals by fostering emotional buy-in to their financial plan. Implementing the 3-stage Iceberg Method for follow-up questions can help clients feel heard and connected, which can deepen and enrich the client/advicer bond, helping engender a trusting and long relationship!

The Power Of Inquiry: Why Follow-Up Questions Are Crucial In Financial Planning

The ability to ask good questions is a crucial skill for financial advisors – understanding a client's financial situation and building a relationship with them often depends on it. Furthermore, asking the right follow-up questions can set great advisors apart from good advisors. While an initial question is needed to get the conversation going, the right follow-up questions can enrich the dialogue and the relationship.

A Harvard Business School study examining the role of question-asking in conversational behavior suggests that asking questions increases likeability and even found that asking follow-up questions during face-to-face speed-dating conversations led to more second dates and deeper relationships! Importantly, though, not all follow-up questions are created equally: For advisors having discussions with clients, the follow-up questions that tend to offer the best results are those that focus the advisor's attention on the client.

Consider the following example in which an advisor asks a follow-up question during a prospect meeting:

Advisor: Can you share with me what brought you in today?

Prospect: Sure, I've been thinking a lot about my ability to retire.

Advisor: Retirement – great! You're in the right place. We help a lot of clients with their retirement planning. May I tell you a little bit about our retirement services?

Note how the advisor quickly shifts the focus of the conversation away from the prospect and compare the flow of the questioning with this example, where the advisor keeps the attention on the client:

Advisor: Can you share with me what brought you in today?

Prospect: Sure, I've been thinking a lot about my ability to retire.

Advisor: Retirement – great! Tell me what you've done so far when considering your retirement; I'd like to hear more about what you've been thinking about…

Both advisors are kind people, and both are interested in helping the prospect. However, in the second example, the advisor has likely increased the probability of winning the prospect as a client with the use of a follow-up question that maintains focus on the prospect.

The key point is not that advisors shouldn't talk about themselves; instead, shifting the conversation away from the prospect or client is best done only after spending some time asking several follow-up questions that focus on the prospect or client. These types of follow-up questions build relationships, increase the information gathered, and create a situation for deeper conversations and better advice.

Imagine visiting the car dealership. The salesperson asks what has brought you in and what you are looking for today, and you tell them that you're thinking about a new car, maybe an SUV or a sedan. The salesperson lights up and replies, "You are in the right place because we have SUVs on the lot right now! You definitely want an SUV – I just bought one and I can't get enough of it. I have so much fun driving it everywhere around town! We have a few different colors in stock, but the red one is definitely for you! I'll have someone drive one out front and we can go on a test drive right now! If you're lucky, we can have you driving out of this lot in your new SUV this afternoon!"

Weird right? It's not necessarily the most confidence-instilling interaction when the salesperson doesn't take the time to ask questions about what you're specifically looking for. How do they know that you want an SUV and not a sedan? How do they know how much you have to spend? How do they know what questions you have about the options you're still considering? The whole interaction has moved too quickly, focusing mostly on their experience with SUVs and not spending any time focusing on your concerns.

Talking about services or attempting to offer professional advice without asking numerous follow-up questions can feel inauthentic to the client or customer and often results in a depersonalized experience. Not only do good follow-up questions lead to better rapport with a client, but they also build trust and encourage better conversations. This helps advisors elicit nuanced details about what really matters to the client. Thus, clarity is often created through good follow-up questions. And motivation to follow through on a financial plan based on what's most meaningful for the client is created through this level of clarity.

Not only does the power of good follow-up questions help advisors by building client relationships and understanding their clients' needs, but asking the right follow-up questions also benefits the prospect or client. Follow-up questions that focus on the client feel good to them; the brain's pleasure center tends to light up when a person has the opportunity to talk about themselves. It is often easy for people to talk about themselves as they know more about themselves than anyone else. It also feels good to feel interesting and important to someone else. And feeling interesting is vital to the longevity of the relationship. Clients are more likely to stay with their advisor when their advisor makes them feel valued and understood.

Fundamentally, follow-up questions can have a significant impact on an advisor's job, playing a key role in gathering critical and nuanced data, creating clarity, and motivating clients. Follow-up questions also strengthen relationships and make the client feel good. Yet, it can be hard to come up with a good stream of follow-up questions that naturally progress the conversation. Many advisors may also wonder how many follow-up questions they should ask to get these benefits. Fortunately, the iceberg follow-up model is a straightforward approach that can help make this easier.

Fact, Situation, Feeling – The Iceberg Follow-Up Structure To Connect With And Motivate Clients

While "Tell me more" can be an excellent follow-up question, asking a client to "Tell me more" 15 times in an hour gets old and can feel awkward. Asking follow-up questions is critical, but how does an advisor spontaneously come up with a variety of good follow-up questions to ask? How many follow-up questions need to be asked? Is there any structure or advice on asking follow-up questions beyond the importance of asking them in the first place? Yes.

Qualitative researchers and professional question-askers have figured out a few good tricks. One of the most straightforward and potent tricks is called the iceberg. The iceberg method involves a 3-question format. 3 questions in succession won't feel like an interrogation (especially when it ends in a summary). Yet, 3 questions can get into the important depth that builds relationships and increases the data collection needed for better advice. The iceberg format has 3 parts that include 1) revealing the client's key facts, 2) understanding the meaning and situational context around the key facts, and 3) exploring the client's feelings and values about their situation.

Nerd Note:

For more good communication techniques, check out the book Listen Like You Mean It: Reclaiming The Lost Art Of True Connection by Ximena Vengoechea. In this book, the author offers advice on conversation and listening skills from professional interviewers, podcast hosts, life coaches, filmmakers, and marriage counselors. There are several useful scripts and exercises that readers can use to practice the ideas and teachings.

Facts: Revealing The Client's Key Issues

Many conversations, especially the ones advisors have in financial planning meetings, begin with a fact-finding question. These fact-finding questions are best structured as open-ended questions, which are questions that encourage the client to share more nuances about their feelings and experiences; they aren't limited to a specific set of options.

For example, compare the 2 sets of questions below; each of the closed-ended questions can be answered very briefly (e.g., retirement, taxes; fine, okay; yes, no), whereas the open-ended questions invite the client to share more details about their circumstances and priorities.

Closed-Ended Questions:

- What is top of mind for you today?

- How are you doing today?

- Have you started saving for your children's college savings?

Open-Ended Questions:

- Share with me what brought you in today.

- Tell me what you have done so far related to college education funding.

- Tell me more about your desire to purchase a new home.

The open-ended questions above are also framed as a command or statement, unlike the close-ended questions that are actual questions. This can be an effective strategy for clients who may consider a statement as less judgmental than a question, and it can also prevent setting an alarm off in the brain that there is any 'right' answer to the question. College funding might not feel emotionally charged to the advisor, but the advisor has no way of knowing if a prospect or new client has big feelings (shame, stress, regret, frustration, guilt) around the issue, and may feel defensive if they perceive that they are being interrogated and judged on what they've done so far.

Open, command-style questions are often the safer way to start a conversation and solicit truthful answers that help the advisor reach the next stage of the conversation, where they mine deeper into the iceberg to learn more about the context surrounding the information just gleaned from the fact-finding stage. Advisors can go much deeper into the next level of the iceberg when they set the stage from the start with open questions that establish positive feelings and provide emotional safety for the client.

Situation: Understanding The Contextual Story

The situation is the next level deeper after fact-finding in the iceberg. Situation questions follow up on the client's answer to reveal more context around the initial fact-finding question: What happened before, what happens next, what makes this necessary, and what makes this urgent? Situation questions are often diagnostic and go beyond the rudimentary level of fact-finding exploration. They function to get to the story around the facts. The following are examples of situation questions:

Tell me, how long has this been going on?

I'm curious: what have you tried up to this point?

Share with me what makes this more urgent or essential than…

Interesting. What would it look like if X were handled/done/fixed…

Notably, like fact-finding questions, situation questions can also be more effective when asked in command/statement form. It cannot be understated how difficult it is to talk about finances, so anything an advisor can do to lessen a client's potential stress or anxiety, especially a simple thing like using a command over a question, can be very meaningful for the client and can lead to valuable conversations that engender trust and connection.

Feelings: Exploring The Client's Emotional State

At the bottom of the iceberg method, beyond fact-finding and situational context, is the process of exploring the client's feelings. Questions that examine feelings ask about emotions. And like the 2 previous steps, the structure of the feeling question is important. Framing these questions as "I" statements or different versions of the "it seems" structure is a crucial detail because people generally don't appreciate being told what they are feeling, such as when an advisor says, "You must be feeling overwhelmed and very stressed by your tax bill." While an advisor may have no negative intentions and may merely be trying to express empathy, such remarks can feel demeaning or patronizing, coming across as dismissive or flippant to the client.

Instead, using an "I" statement or an "it seems" is a safer approach:

- It appears that your tax bill is larger than last year's. Can you tell me how you're feeling about that?

- I've noticed that you've mentioned your daughter's student loans a few times. Can you tell me how the refinancing process is going for you?

- I'm interested to hear about how you're feeling about that…

- It seems like there could be concern about market volatility. Can you share how you're feeling about this risk?

Feeling questions are important because motivation is ultimately driven by feelings. Which means that tapping into a client's feelings can be an effective way to build motivation. Advisors strive to ensure that their advice is valued (and followed!) by clients and discussing how a client feels about their plan can be a powerful way of connecting and revealing the deeper feelings that drive and inspire clients to commit to their financial goals and the necessary steps to achieve them.

The iceberg follow-up model is a powerful and simple approach for building rapport and motivation simultaneously during prospect and discovery meetings. While fact-finding questions identify the client's key concerns, situation questions help the advisor gain context and build rapport to make their advice more personal and relevant. And questions that explore the client's feelings build up motivation for the client to take and follow the advice in their financial plans.

Using The Iceberg Follow-Up Model In Prospect And Discovery Meetings

When used in prospect and discovery meetings, the iceberg follow-up model can be an excellent tool that can cultivate connection and motivation – both important elements that are essential to establish successful client relationships.

Advisors can start by asking open-ended fact-finding questions. For example, what has driven a prospect to call the financial planner? What needs does the prospect have that a financial planner might be able to help with and figure out?

Some common examples of command/statement questions are as follows:

- Tell me a bit about what brought you in.

- Tell me about your financial ecosystem.

- Share with me a financial goal that you would like to accomplish in the next year.

Next, move to situation questions that ask the client to provide background information around their main concerns revealed through the fact-finding question. In addition to better understanding the client's situation and establishing rapport, these questions help the advisor to offer advice that is more personal and relevant to the client.

Some examples of situation questions are as follows:

- Tell me how long this has been going on.

- Great! Share a bit about what has happened up to this point.

- I'm curious; what have you tried up to this point?

Finally, close with feelings questions that help advisors understand what motivates the client. Change is hard, and by tapping into emotions, advisors can help prospects and clients move forward more effectively.

Some feelings questions that advisors can use are as follows:

- Thank you for indulging me. Tell me how that makes you feel.

- I appreciate all of this information. It seems that this is a major concern for you. Can you share with me what you're feeling about that?

- This additional information is so helpful; I'm interested to know how that makes you feel.

Below is an example dialogue between Lara, a prospect, and her future advisor, Tom. Tom uses the iceberg model to help Lara feel more comfortable and build a connection with her. Lara contacted Tom because Tom is also her friend Tina's advisor.

Tom: Welcome, Lara. It's so great to meet you!

Lara: Thanks, Tom. I'm glad to be here. Tina has said a lot of great things about you.

Tom (smiling kindly): Tell me, Lara, what is top of mind for you today?

[fact-finding question]

Lara: Well, I have a lot going on at work, and I recently came into some money. I think I just need to talk to someone.

Tom: You're in the right place – I enjoy talking with my clients about money, and I'm also inquisitive. Tell me what you mean by "came into some money".

[situation question]

Lara: Yes. Okay. I've been working for this tech company and we're going to go public. I was just granted a bunch of stock options, and I have to make some decisions. I think I'm going to have a tax bill from all this and I'm just not sure where to start.

Tom: Wow, it sounds like a lot is going on. There are so many changes all at once. It seems like figuring out a way to organize all this new information could be helpful. Tell me how you're feeling about the situation.

[feelings question]

Lara: Feeling organized would definitely be helpful because right now, I'm just feeling overwhelmed and confused by the process.

Tom: I appreciate you sharing that with me. Let's talk a little bit about…

In the dialog above, Tom uses the iceberg approach to learn what is going on with Lara. While Lara reveals that she is coming into money in response to Tom's fact-finding question, her response to Tom's situation question further clarifies that the source of the money is her company's new stock option plan. This helps Tom further refine his follow-up.

Because Lara notes that she's not sure where to start, Tom understands that Lara is feeling confused and probably wants to better understand the process. When Tom begins to explore Lara's feelings, he uses an "it seems" statement by noting, "It seems like figuring out a way to organize all this new information could be helpful." Notably, he doesn't tell Lara that he knows how she feels or that getting organized will make her feel better. Instead, he asks her to tell him how she feels before he goes on to discuss what they can do together to proceed. By asking Lara to confirm that getting organized will be helpful, Tom better understands something that will motivate Lara while helping her feel heard at the same time. Their advisor-client relationship is off to a good start.

Advisors dedicate themselves to mastering the art of communication with clients, and follow-up questions are key tools in this skill set. By employing the Iceberg Method for follow-up questions, advisors can engage clients in relevant and meaningful conversations that ensure clients feel heard and connected. Furthermore, using the fact, situation, and feeling approach of the Iceberg method can help advisors foster a deeper sense of motivation and trust in clients, laying the foundation for lasting client relationships!

Leave a Reply