Executive Summary

Most of the time, people are subject to state taxes in the states where they live and/or earn their income. So when moving to a lower-tax state or another, their income tax burden likewise shifts to the new state along with them. Which is, for example, why so many people opt to move to lower-tax or no-tax states like Florida or Texas in retirement, where they can enjoy lower state income taxes and preserve more of their retirement savings for use by themselves or their heirs.

But like many rules, there's an exception: When a person working in one state defers some of their income, then moves to a different state (where they ultimately receive the income), that income can in certain cases be taxed by the first state (where they worked when they earned the income) even when the person now lives in a different state. In other words, moving to a lower-tax state won't always result in paying lower state taxes with particular types of income.

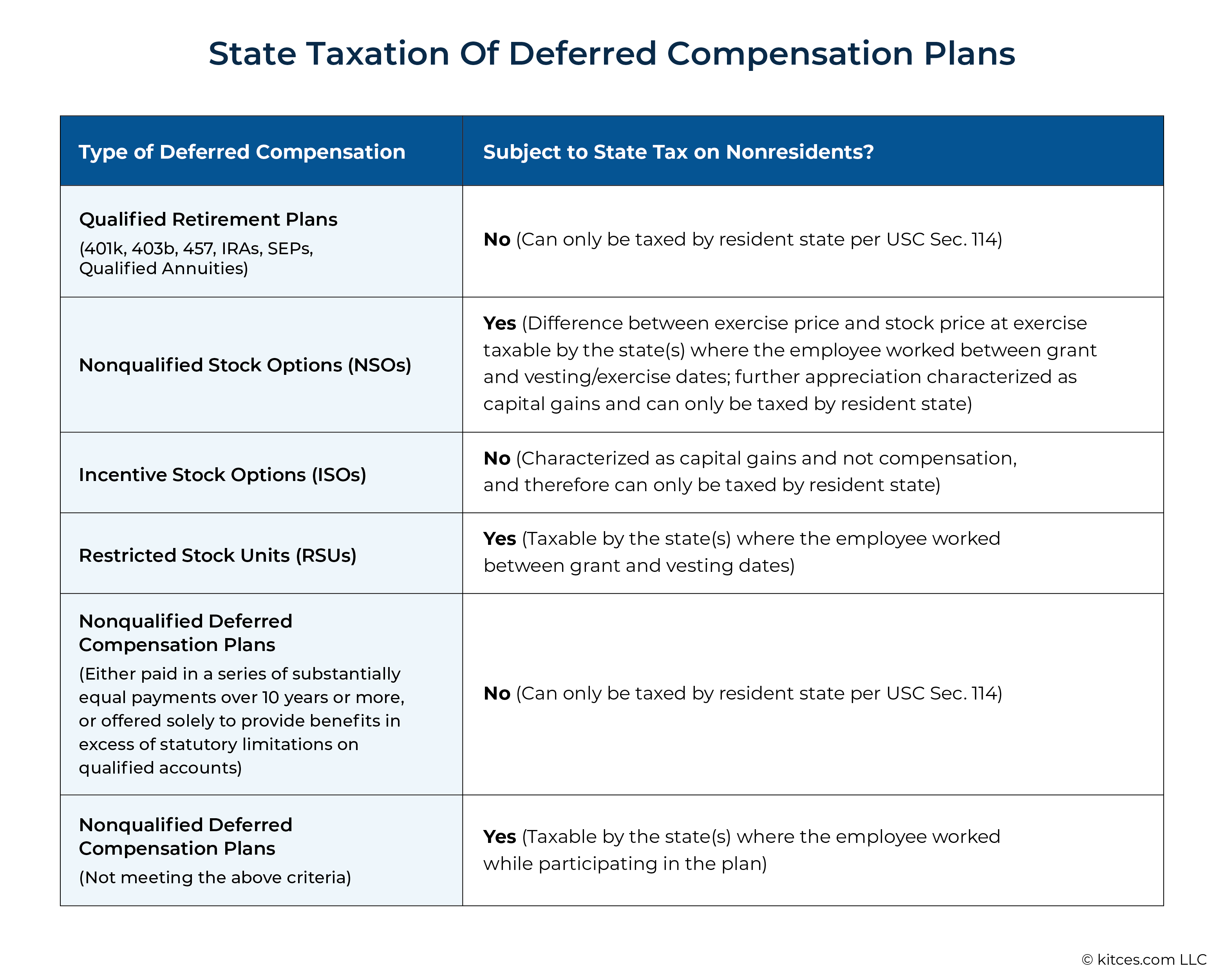

Specifically, USC Section 114 defines certain types of "retirement income" that can only be taxed by the states in which a person resides, which include qualified employer retirement plans and IRAs as well as nonqualified deferred compensation plans that are either paid out over a period of at least 10 years or structured as an excess benefit plan. However, other types of deferred income, including equity compensation plans like stock options and RSUs (which generally aren't taxed until after a multiyear vesting period) and nonqualified deferred compensation plans that don't meet the specific criteria above, can still be taxed by the state in which that income was initially earned, even after the employee moves to a different state.

For advisors of employees who want to minimize their state tax burden in retirement, then, understanding the different types of deferred income they may be receiving – and how (and by which states) it will be taxed – can help to recognize planning opportunities that help ensure the client's goals of lower taxes are actually met. For example, some strategies around employee stock options plans, such as utilizing Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) or making an 83(b) election on Nonqualified Stock Options (NSOs), cause income from those options to be recognized primarily as capital gains, which would be taxable only in the state where the employee lives when they actually sell the underlying stock. And for employees with access to nonqualified deferred compensation, confirming that the plan's benefits pay out as a series of substantially equal periodic payments over at least a 10-year period ensures that they meet the definition of "retirement income" under Section 114. (And because nonqualified deferred compensation is traditionally offered only to executives and other key employees, those employees may be able to influence how the plan is set up to begin with to ensure the best tax treatment!)

The key point is that when someone moves to a different state for tax purposes, sometimes the move itself isn't enough on its own to accomplish that goal, and more careful planning is necessary to see meaningful tax savings when deferred compensation is part of the financial picture. Which ultimately means that advisors with a deeper knowledge of the state tax treatment of deferred income can help make sure that their clients' expectations of lower state taxes in retirement match up with the reality.

The topics of sports and taxes don't often show up in the same story, but those subjects experienced a rare convergence in December of 2023 when the Japanese baseball star Shohei Ohtani signed a 10-year, $700-million contract to play for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Aside from being, in nominal dollar terms, the largest contract in the history of professional sports, the most notable thing about Ohtani's contract with the Dodgers – and what has piqued the interest of financial and tax professionals – is that over 97% of the contract's value ($680 million of the $700-million total) is to be deferred until after the contract ends. Specifically, the Dodgers will pay Ohtani $2 million per year for the 10 years that he is actually playing under the contract… and then $68 million per year for the 10 years thereafter, during which time he might be playing for a different team or even retired from baseball entirely.

While the sheer amount of money being deferred for a decade-plus raises a number of intriguing financial planning questions – from how much the contract's value could be eroded over time by inflation to how to manage the potential risk of the Dodgers declaring bankruptcy and defaulting on his payments – one question that has sparked particular debate is whether Ohtani will need to pay California state tax on the full $700 million value of the contract, or on just the $20 million that he will earn during the 10-year period when he is actually playing (that is, working) in California.

If it's the former (the possibility of paying the tax on the full value of the contract), then Ohtani would pay the top marginal California tax rate of 14.4% on virtually all of the contract's value (since the top bracket applies to earned income above $1 million, and Ohtani also earns millions in income from endorsements each year), amounting to 14.4% × $700 million = $100.8 million in California state tax alone. But if it's the latter (the possibility of paying the tax on only the first 10 years of earnings), then, at least in theory, Ohtani could finish the first 10 years of his contract having paid California state tax on the $20 million of non-deferred income, equaling 14.4% × $20 million = $2.9 million, and then move to a zero-income-tax state like Florida or Texas to receive the remaining $680 million in deferred income while paying zero state tax. In other words, the difference between Ohtani paying California state tax on his entire contract, or just during his playing years, could add up to $100.8 million – $2.9 million = $97.9 million!

The answer to whether or not Shohei Ohtani's contract really makes it possible for him to save nearly $100 million in state taxes lies in the details of the contract itself – which aren't known to anyone besides Ohtani, the Dodgers, and their respective lawyers – so it isn't possible to know whether it really constitutes the tax bonanza that it's speculated to.

However, the Ohtani example does provide an interesting reminder of how significant the tax planning opportunities can be around deferred income, particularly when moving from one state to another. Because while Ohtani's fame and the uniqueness of his contract have garnered a lot of attention to his case, the reality is that many workers – not just those earning $700 million as professional athletes – end up earning the majority of their lifetime income in higher-tax states, deferring some of their salary during their working years, and moving to a lower-tax location after retirement. Which makes it helpful to know which types of income will actually be taxed at the lower rate after moving between states – because although some types of deferred income are taxable only in the state where they're received (creating the opportunity to save taxes by deferring income and then moving to a lower-tax state), other types can be taxed by the state where they were earned, which offers its own tax planning challenges and opportunities.

How States Tax Income For People Living (Or Working) In Their State

At a high level, states that have an income tax generally tax all income earned by taxpayers who are residents of that state, no matter where that income was earned. Additionally, they also tax income earned by nonresidents if that income was earned while working in that state. Which sets up an obvious conflict in situations where a taxpayer lives in one state but works in another, since, in theory, both states could impose taxes, leading the taxpayer to pay state tax twice on the same income.

However, this 'double taxation' can usually be avoided: Many states have reciprocity agreements with other states, which allow residents to live in one state and work in another while only being subject to taxes in their home state. And even when there isn't reciprocity, states generally allow their residents to claim tax credits against taxes paid to other states, reducing the taxpayer's tax liability to their home state by the amount that they pay to the state where they work. So in most cases, a taxpayer who lives in one state while earning income in a different state effectively only has to pay tax on that income to one state.

Nerd Note:

Some people who work remotely can also owe taxes to the state where their employer is based – even if they don't physically work in that state – if the employer is located in Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, or Pennsylvania. All of those states impose taxes on employees who work remotely "at the convenience of the employer", regardless of where they physically do the work.

Retirement Income Can't Be Taxed By States For Nonresidents

But those are just the rules for someone living in one state and working in a different state at the same time. Things work differently when a person lives and works in one state while deferring a portion of their income, and then moves to a different state where that deferred income is ultimately received, as is the case, for example, when a person moves to a different state upon retirement and begins withdrawing from their 401(k) plan.

As deferred compensation arrangements (including 401(k) and pension plans) grew in popularity in the latter half of the 20th century, states became increasingly aggressive in claiming the right to impose tax on deferred income earned by retirees who had moved to different states. This was particularly true for higher-tax states like New York and California, which saw a steady stream of workers decamping to low- or no-tax states like Florida upon retirement, and subsequently contended that since they were the states where those workers had originally earned their income, then they ought to have the right to tax it. Which made at least some amount of sense, since that was how states already taxed income that was earned in one state while living in another; the only difference was the time delay in actually receiving the income that was deferred.

In 1995, however, the U.S. Congress intervened to (mostly) settle the matter of who gets to tax deferred income when it passed the State Taxation of Pension Income Act, which created USC Section 114. In a nutshell, Section 114 makes it illegal for states to impose taxes on "retirement income" of nonresidents. More specifically, it states the following:

No State may impose an income tax on any retirement income of an individual who is not a resident or domiciliary of such State (as determined under the laws of such State).

In other words, individuals receiving "retirement income", as defined by Sec. 114, can only be taxed on it by the state where they currently live, regardless of the state they worked in to actually earn the income.

Section 114 goes on to define the types of retirement income that can only be taxed by a resident's home state. These include virtually all types of qualified retirement plans (e.g., 401(k), 403(b), and 457 plans), IRAs (including SEPs for self-employed workers), and qualified annuities.

Additionally, nonqualified deferred compensation plans, such as those used to provide additional benefits to executives or key employees, are also included, as long as they are paid out in a series of "substantially equal periodic payments" over a period of at least 10 years.

Not All Deferred Income Is Considered Retirement Income

But even though USC Section 114 specifies a wide swath of different types of income as "retirement income" (which makes certain that most retirees, who rely mainly on distributions from 401(k) plans, pensions, or annuities for their retirement income, will only be subject to income tax in the state where they reside), it doesn't cover all types of deferred compensation. If deferred compensation doesn't meet the definition of "retirement income" as laid out by Sec. 114 – even if it's actually received during retirement – then it can potentially be taxed by the state where it was earned, which would complicate the plan of moving to a lower-tax state in retirement for the tax benefits alone.

Modern companies use a wide variety of different compensation structures to attract and retain talent. In many cases, these plans involve deferring at least some of the compensation, not just for the purposes of deferring taxable income, but also to incentivize employees to stick around for the long term (since, in many cases, the deferred income can be forfeited if the employee doesn't remain with the company for a specified length of time). And notably, not every type of deferred compensation qualifies as "retirement income" under Section 114, which means that states can (and often do) try to tax such deferred income when it was earned in the state, regardless of whether the employee moved to another state before receiving the income.

Equity Compensation Plans

One of the most popular categories of compensation outside of traditional salary and bonuses is equity compensation, which includes stock options, Restricted Stock Units (RSUs), and stock appreciation rights, among other types of plans. In most cases, income from equity compensation plans is paid on a vesting schedule: The compensation is granted on a certain date, but the employee must wait a number of years until they can actually realize its economic value (by exercising the options and/or selling the stock shares). And in general, the income from these plans isn't taxed until the latter date, when the employee realizes the income – making it a form of deferred compensation that doesn't count as "retirement income" for the purposes of USC Section 114 and thus potentially subject to taxation by the state where the employee lived when the income was earned.

It's worth going over a few of the most common types of equity compensation plans that do not qualify as "retirement income" according to USC Section 114 to illustrate how they might be taxed by a state other than the one in which the employee lives when they receive the income.

Nonstatutory Stock Options (NSOs)

The most common method of offering equity compensation is to offer an Employee Stock Option (ESO) plan. In general, companies grant ESOs to the employee (which gives them the right to buy the company's stock at a specified 'exercise' price), and after a specified period of time (known as the vesting period), the employee can exercise the options and buy the stock at the exercise price, which is generally less than the stock's actual fair market value at that time. After exercising the options, the employee can sell the stock and benefit from the difference between the exercise price and the price at which the stock is sold.

What's important to note is that at both the Federal and state level, taxation for stock options plans that are treated as Nonstatutory Stock Options (NSOs) is usually deferred until either the date the options become vested (for most publicly traded companies with a "readily determined fair market value", as defined in IRS Publication 525) or the date they're exercised (for most privately owned companies, which don't have a readily determined fair market value). The amount taxed as compensation equals the difference between the option's exercise price and the price of the stock on the vesting or exercise date.

Example 1: Mona works for a publicly traded company and is granted 10 Nonstatutory Stock Options (NSOs) that will be taxable on the date they become vested. The options have an exercise price of $100 and will vest after 5 years.

At the time the options vest, the stock is trading for $200 per share. Because Mona's employer is a publicly traded company, the NSOs have a readily determined fair market value and thus are taxed based on their vesting date.

The amount that is taxable as wages to Mona equals the difference between the price of the stock at the vesting date and the options' exercise price, times the number of options granted, or ($200 − $100) × 10 = $1,000.

States tend to consider income from the exercise of NSOs to be taxable in that state if the employee lives and/or works in the state during the period between when the options are granted and when they are vested or exercised. For example, my home state of Minnesota allocates income from NSOs to Minnesota based on the ratio of the days worked in the state during the period between the grant and vesting dates of the options.

What's key to remember is that stock options – specifically, the difference between the exercise price and the stock's trading price when the option is vested or exercised – are taxed as compensation. Any additional capital gains that might take place between the vesting/exercise date and when the stock is sold are treated as capital gains and only taxable in the individual's resident state in the year of the sale.

Which ultimately means that if someone is living or working in one state when they're granted options, and then moves to a different state before the options are exercised and/or vested, at least part of the income that is realized on exercise or vesting could be taxed by the state where they earned the income, even though they're now living in a different state.

Example 2: Mona in the example above is granted 10 NSOs with an exercise price of $100 that vest after 5 years. When the options are granted, Mona lives and works in Minnesota; however, in the fifth year, AA moves to Texas (which has no state income tax), where she works remotely.

If the stock is trading at $200 per share on the vesting date, Mona will be taxed on ($200 − $100) × 10 = $1,000 of income. Because she lived and worked in Minnesota for 4 out of the 5 years between when the options were granted and when they vested, 4 ÷ 5 = 80% of the income from the options will be subject to Minnesota state tax.

In other words, in the year the options vest, Mona will pay Minnesota state taxes on 80% × $1,000 = $800 of income, even though she is now living in the tax-free state of Texas.

The Potential State Tax Benefits Of Section 83(b) Election For Nonstatutory Stock Options (NSOs)

Many employees who receive NSOs as compensation take advantage of the Section 83(b) election that allows them to pay tax on the difference between the option's exercise price and the stock's trading price as of the grant date, not the exercise or vesting date, with any additional appreciation being taxed as capital gain when the stock is ultimately sold.

On the one hand, this effectively ensures that the compensation part of the option will be taxed entirely in the state where it was earned (since the employee would presumably be working in that state when the option was granted). On the other hand, the 83(b) election also means that a greater portion of the income from the option will likely be taxed as capital gains income, which will only be taxed in the state where the employee lives when they ultimately sell the stock.

In other words, while making an 83(b) election is often considered for Federal tax purposes because it can subject more of the income from the sale to generally lower capital gains tax rates, it can also save taxes on the state level for someone who moves to a lower-tax state before selling the underlying stock.

Example 3: Mona from the previous examples is granted 10 NSOs with an exercise price of $100 that vest after 5 years. But instead of waiting until the options vest to be taxed on the income, she makes a timely 83(b) election to be taxed based on the share price as of the grant date, not the vesting date.

If the stock is trading at $125 as of the grant date, making the 83(b) election results in paying Minnesota state taxes on ($125 − $100) × 10 = $250 of income.

If, as in the example above, she moves to Texas in the year the options vest and then sells the stock at $200 per share immediately on vesting, then the remaining income of ($200 − $125) × 10 = $750 is only subject to taxation in Texas – and since Texas has no state tax, Mona will pay $0 in tax on the income.

In other words, by making the 83(b) election, Mona pays state taxes on only $250 of income on her NSOs, versus paying state tax on $800 without the election (as in the example above).

Incentive Stock Options (ISOs)

Another type of common stock option plan, Incentive Stock Options (ISOs), has a different tax treatment from Nonstatutory Stock Options (NSOs). Unlike NSOs, where the income from the option is characterized partly as compensation (for the difference between the exercise price and the stock's price upon vesting/exercise of the option) and partly as capital gain (for any additional appreciation of the stock), the income from ISOs is characterized entirely as capital gain, as long as the employee holds the stock for at least 2 years beyond the date the option is granted, and for at least 1 year beyond the option is exercised. Furthermore, taxation of ISO income is deferred until the underlying stock is ultimately sold.

The fact that ISOs are taxed as capital gains and not compensation means they're only taxable in the state where the employee lives when they sell the underlying stock.

Example 4: Byron lives and works for a startup company in California. He is granted 10 ISOs with an exercise price of $50, which vest after 3 years. Byron exercises the options immediately on vesting and moves to Tennessee the following year. The year after that, he sells the stock from the exercised ISOs, which are now trading at $150 per share.

At the Federal level, Byron will be taxed on the difference between the option's exercise price ($50) and the price at which he sold the stock ($150), or ($150 − $50) × 10 = $1,000, which will be subject to capital gains tax rates.

At the state level, the $1,000 of income from the shares will only be taxable by the state of Tennessee, where he lived when he ultimately sold the stock. Since Tennessee has no state income tax, Byron will pay no state taxes on his ISO income.

Restricted Stock Units (RSUs)

While stock option plans allow employees to buy company stock, often at a discount to the stock's actual trading price, some companies take a more direct approach to equity compensation by simply giving stock to their employees without requiring them to put up their own cash to buy the stock as would be the case with options. Many companies subject their direct equity compensation to a vesting schedule, where the employee must keep working for the company for a certain number of years before they actually own (and are able to sell) the stock, in which case the equity compensation is usually known as Restricted Stock Units (RSUs).

Unlike stock option plans, where the Federal and state taxation can vary depending on whether the plan is an NSO or ISO plan and whether an 83(b) election is made, the taxation of RSUs is fairly straightforward: Employees are taxed on the full value of the stock on the date it vests. What's more, all of that income is taxed as compensation (as opposed to being partially or entirely characterized as capital gain, as is the case with most employee stock option plans), making it taxable at least to some extent in the state(s) where the employee worked between the time that the RSUs were granted and when they became fully vested. And unlike stock option plans, no 83(b) election is allowed for RSUs, meaning there's no option to pay tax early on the grant in order to subject more of the income to capital gains taxes.

For state tax purposes, RSUs are usually taxed by states based on the proportion of time during the vesting period when the employee worked in the state.

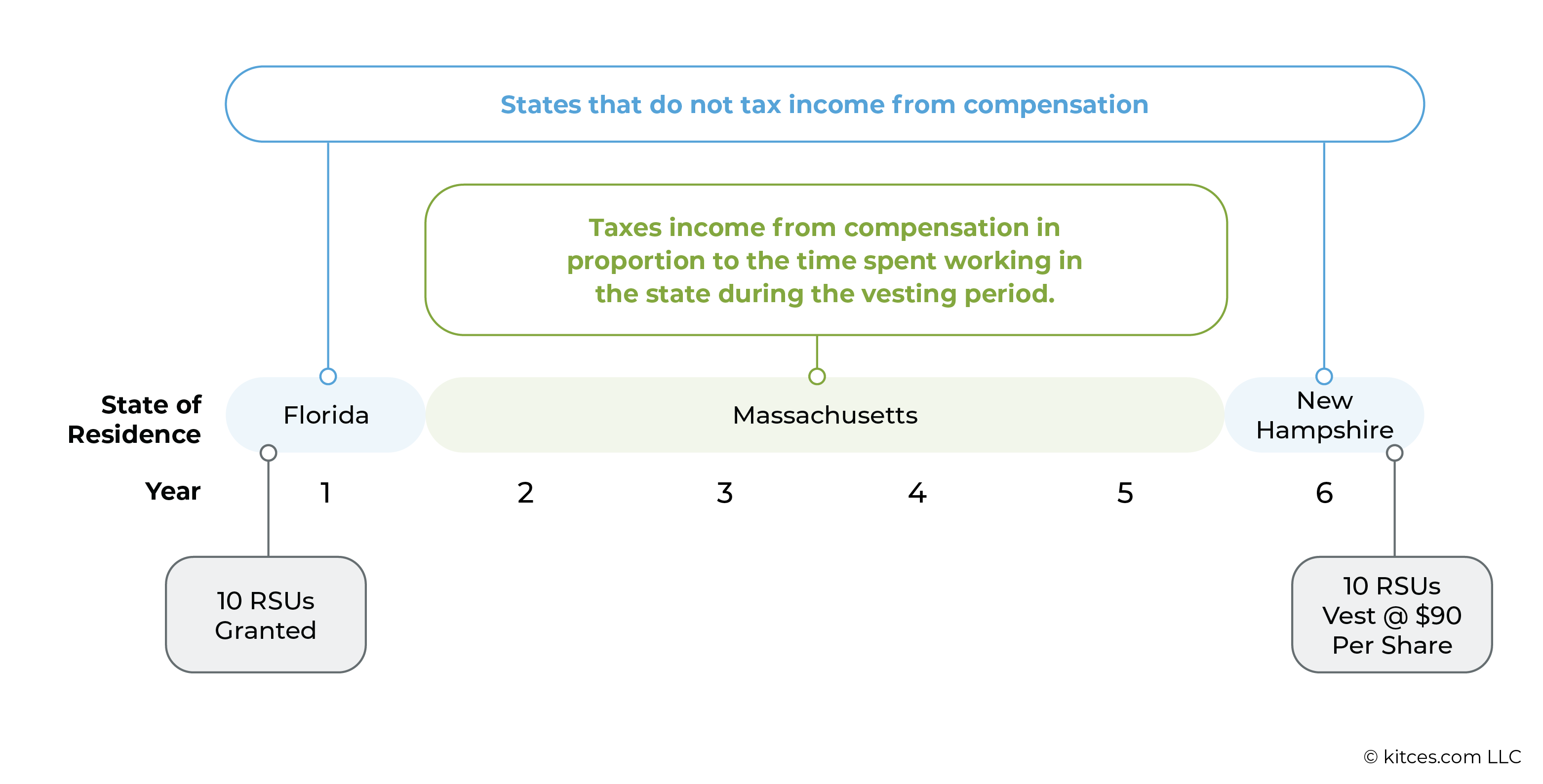

Example 5: Valerie's employer granted her 10 RSUs while she was living and working in Florida, with the RSUs vesting after 6 years. After year 1, Valerie moved from Florida to Massachusetts, where she worked from year 2 through year 5. After year 5, she moved to New Hampshire, where she worked until the shares vested at the end of year 6. Upon vesting of the RSUs, the employer's stock was worth $90 per share.

Neither Florida nor New Hampshire taxes income from compensation. However, Massachusetts taxes compensation income from RSUs in proportion to the time employees spend working in the state during the vesting period.

For Federal tax purposes, Valerie will be taxed on the full value of the shares upon vesting, or $90 × 10 = $900.

For state tax purposes, Valerie will owe no state tax to Florida or New Hampshire. But Massachusetts will tax Valerie on the income from the RSUs in proportion to the time she spent working there during the 6-year vesting period.

Because she worked in the state for 4 out of the 6 years, Valerie will be subject to Massachusetts state tax on (4 ÷ 6) × $900 = $600 of the RSU income, even though she lives in no-tax New Hampshire when the RSUs actually vest.

There are other types of equity compensation plans that exist, such as stock appreciation rights and phantom stock plans, but the taxation of income from those plans is similar to that of RSUs: The income is taxed in the year it's vested, but it's generally subject to state taxes anywhere that the employee worked during the vesting period regardless of where they live or work during the actual vesting year.

In other words, the only type of equity compensation plan that generally isn't subject to state taxes based on where the employee worked while earning the compensation is an Incentive Stock Option (ISO) plan, where the income is characterized entirely as capital gains rather than wages or compensation.

For any other type of equity compensation plan, moving to a lower-tax state before actually receiving the income (in the form of exercising the option or receiving the company stock or other equity-based income) won't necessarily result in lower state taxes if the employee worked in the higher-tax state between the grant date and the vesting or exercise date of the shares or options they received.

Which is why it might make sense, if the goal is to eventually move to a lower-tax state anyway, to consider moving earlier (if there's a possibility of working remotely or in another office of the company) in order to reduce the amount of the equity compensation income that is subject to tax in the higher-tax state. This would only make sense for employees with a large amount of equity compensation where the idea of uprooting and moving earlier than planned would be worth it for the tax savings, as in those cases, moving to a lower-tax state might be the only way to realize meaningful tax savings.

Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans

"Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plan" is really a catchall term referring to any plan providing for deferral compensation that doesn't meet the definition of a qualified employee plan. They may go by names like Supplemental Executive Retirement Plan, Top-Hat Plan, Excess Benefit Plan, Rabbi Trust, or many other names depending on their specific characteristics, but the one trait that these plans share is that they involve a "substantial risk of forfeiture" (meaning, for instance, the plan's assets could be subject to the claims of the company's creditors in the event of bankruptcy, which isn't the case with traditional qualified plans). The substantial risk of forfeiture allows the taxes on benefits paid from nonqualified deferred compensation plans to be deferred until the recipient actually receives benefits from the plan.

USC Section 114 doesn't include all types of nonqualified deferred compensation in its definition of "retirement income" that can't be taxed by states for nonresidents (e.g., those that worked in one state and then moved to another for retirement), but it does include specific carveouts for nonqualified plans that are in writing and structured in certain specific ways. Namely, there are 2 conditions under which payments from a nonqualified deferred compensation plan can qualify as "retirement income":

- The payments are received as part of a series of substantially equal periodic payments, made for either the life expectancy of the recipient or a period of at least 10 years; or

- The payments are under a plan maintained solely for the purpose of providing retirement benefits in excess of the statutory contribution limits on qualified retirement plans (which is commonly known as an "Excess Benefits Plan").

In other words, if the nonqualified deferred compensation plan has lifetime benefit payouts (as with a pension) or is structured to pay out over at least a 10-year period, those payments would be considered retirement income and can only be taxed by the state where the recipient lives, not where they worked to earn the benefits if they did so in a different state. (Notably, the payments need to be "substantially" equal, but can include incremental changes by a predetermined formula or cost-of-living adjustments and still qualify for this treatment.)

Likewise, if the deferred compensation plan was an excess benefit plan offered solely to provide employees with supplemental retirement benefits in excess of what's allowed under traditional qualified plans, that plan's payments can also only be taxed by the state where the recipient lives when they actually receive the benefits.

In all other cases – if, for example, the plan has a payout period of less than 10 years and isn't an excess benefit plan – the payments can be taxed by the state in which the employee worked while earning the deferred compensation, even if they live in a different state when they receive the compensation. As with the rules around equity compensation, the amount subject to tax in a state is usually based on the percentage of time worked in that state while earning the deferred compensation.

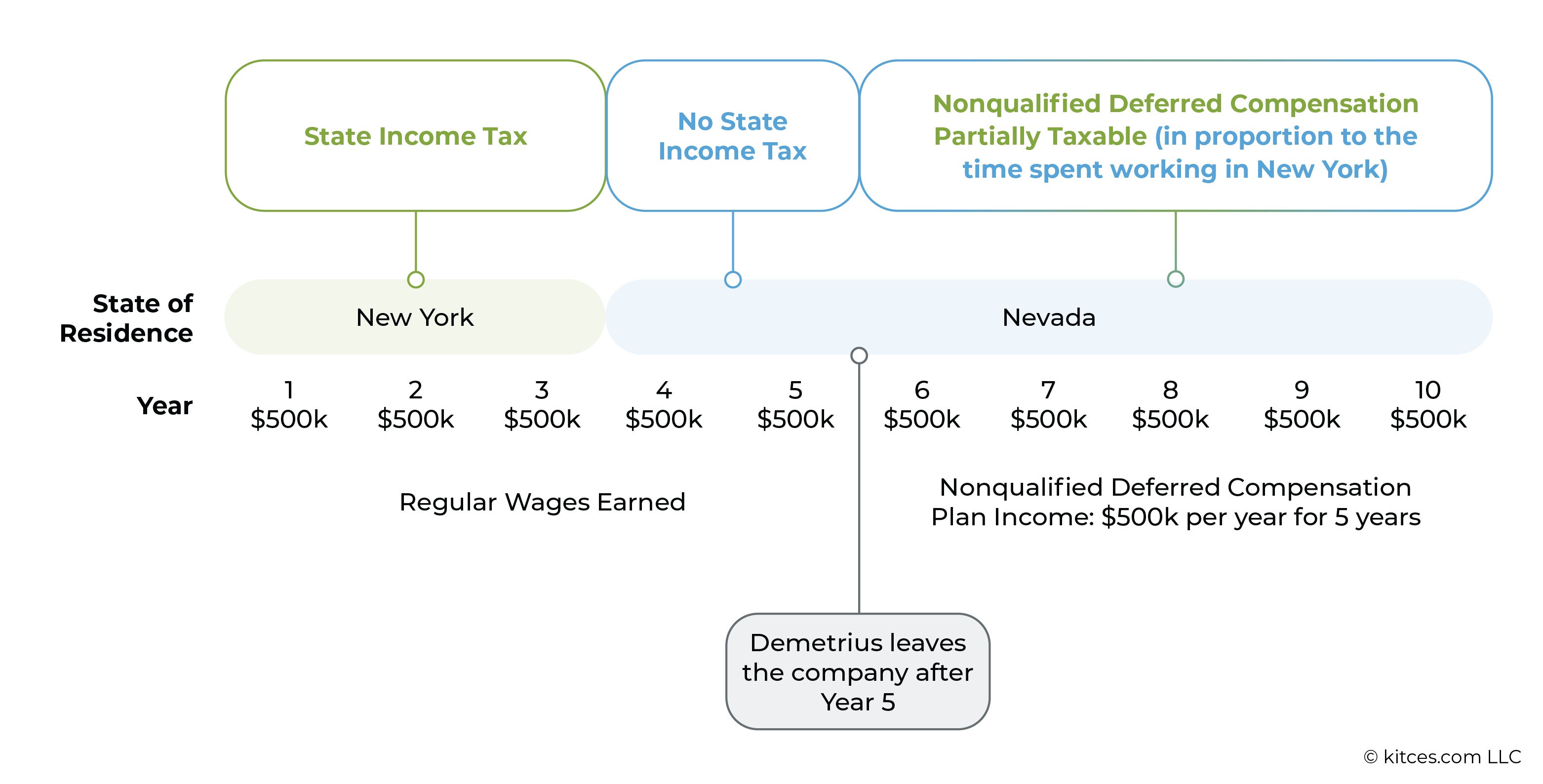

Example 6: Demetrius works as an executive for a large company that pays him $1 million per year over a 5-year period, during which he contributes half of his income ($500,000) into a nonqualified deferred compensation plan. As a result, of the $1 million he's paid each year, $500,000 is taxed in the year in which it's earned, and $500,000 is deferred until it's actually received from the deferred compensation plan.

Demetrius lives and works in New York (which has a state income tax) for the first 3 years, then moves to Nevada (which has no state income tax) and works at the employer's office there for the final 2 years.

The deferred compensation plan will pay Demetrius $500,000 per year during the 5-year period after he leaves his employer.

Because the plan doesn't meet the definition of "retirement income" that is exempt from state taxation by the state in which it was earned, part of the payments (proportional to the amount of time in which Demetrius worked in New York during the 5-year period that he worked for his employer) will be subject to New York state income tax.

Demetrius worked in New York for 3 of the 5 years, so (3 ÷ 5) × $500,000 = $300,000 of each annual payment ($1.5 million of income in total) will be taxed by New York, even though DD is living in tax-free Nevada.

Although it isn't always possible to decide how one's deferred compensation package is structured, the fact that many of these plans are reserved for key employees like executives (or star baseball players) often means the employee can have at least some say in negotiating how the benefits will take shape.

If it's possible to ensure that benefits from a nonqualified deferred compensation plan take place over at least a 10-year period, that can help ensure that moving to a lower-tax state before receiving those benefits will actually result in lower taxes.

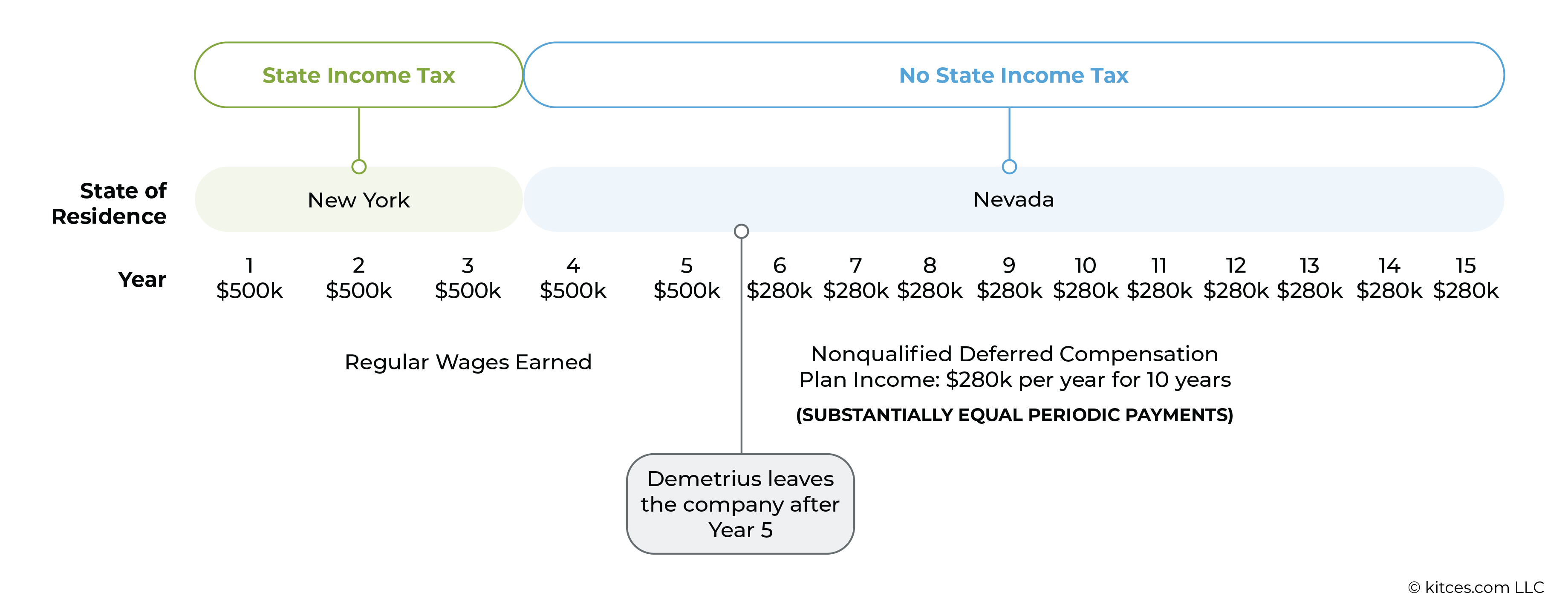

Example 7: Imagine that Demetrius, from the example above, was able to renegotiate his deferred compensation package so that instead of receiving 5 annual payments of $500,000 in years 6–10, he receives 10 annual payments of $280,000 in years 6–15 (receiving slightly more in nominal dollars to compensate for deferring a higher portion of the income).

Because the benefits now consist of substantially equal periodic payments over a 10-year period, they meet the definition of retirement income under USC Section 114 and are no longer taxable by New York after DD moves to Nevada.

So, instead of having $1.5 million of his $2.5 million deferred compensation income taxed by New York as in Example 6, DD will have $0 of it taxed simply by adjusting the structure of his deferred compensation schedule!

From a compensation and benefits planning perspective, then, it's clear how nonqualified deferred compensation plans that meet Section 114's criteria for retirement income (like excess benefit plans or plans that pay out over at least a 10-year period) can be more valuable than those that don't, at least for those for whom moving to a lower-tax state upon retirement is a likely possibility.

Planning Opportunities To Minimize State Tax On Deferred Compensation

As shown in the summary graphic below, different methods of deferred compensation – qualified retirement plan, nonqualified stock options or incentive stock options, restricted stock units, or nonqualified deferred compensation plans that do or do not meet USC Section 114's criteria for retirement income – can have a wide variety of ways of being taxed at the state level.

For employees who want to minimize their state tax burden in retirement and whose retirement savings consist entirely of assets either in qualified plans or nonqualified deferred compensation plans that meet the criteria for retirement income under Section 114, simply moving to (or at least establishing domicile in) a lower- or no-tax state immediately after retirement will do the trick. Once a taxpayer is a resident of their new state for tax purposes, their old state has no ability to tax any income that's covered by Section 114.

But when it comes to deferred compensation from an employer plan that doesn't count as retirement income within Section 114, simply moving to a low- or no-tax state upon retirement won't necessarily result in paying lower taxes on the income from those plans. If there is any possibility of moving to a lower-tax state upon retirement, there are some planning strategies, as summarized below, that can help to reduce the amount that can be taxed by the higher-tax state where the income was earned.

- For employees with compensation in the form of stock options, making use of Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) if available, or making an 83(b) election upon being granted Nonqualified Stock Options (NSOs), can maximize the amount of income treated as capital gains rather than compensation, and is therefore only subject to tax in the state where it's realized;

- For employees with RSUs and other equity compensation plans, moving to a lower-tax state early in the period between the grant and vesting dates of the stock can minimize the amount that is allocated to, and therefore subject to tax from, the higher-tax state where the employee worked when the RSUs were initially granted; and

- For those with access to nonqualified deferred compensation plans, structuring the plans to meet Section 114's definition of retirement income (either by being excess benefit plans or by paying benefits in a series of substantially equal payments over at least 10 years) ensures that the income received from the plan can only be taxed by the state in which it's received, not the state in which it was originally earned.

Taxes loom large as a concern for many people in planning for retirement, and state tax considerations can play an outsized role in the decision of where to move after one's working years. But if someone decides to relocate primarily for tax reasons, it only really makes sense to do so if it actually results in paying lower taxes.

So for workers who are earning certain types of compensation, like equity compensation and non-qualified deferred compensation that's deferred until it's actually received but doesn't qualify as "retirement income" under USC Sec. 114, it makes sense to plan around how that compensation will be taxed at the state level to ensure that the expectations match up with reality. It isn't necessary to be earning Shohei Ohtani levels of compensation to make state taxes a part retirement planning!