Executive Summary

Small business owners often treat their businesses not only as their source of income during their working years, but also as an asset that can be sold to fund their retirement. And while many businesses can build up substantial value over the years, the downside is that, when that value is realized upon the sale of the business, a large amount of it is treated as taxable income. And for many business sales that create capital gains of more than $500,000, the one-time spike in taxable income created by selling a business can bump the seller into a higher income tax bracket, requiring them to forfeit a significant chunk of their funds needed for retirement to pay their own tax bill on the sale.

One way to reduce the tax impact of selling a small business is by using an installment sale. Under IRC Sec. 453, capital gains on the sale of assets, such as privately held businesses where the payments are spread out over a period of 2 or more years, are deferred until the years when the payments are actually received. Which not only defers the taxes owed on the sale to future years, but can also reduce the absolute amount of tax on the sale by spreading out the tax impact over multiple years and keeping the seller within the lower capital gains tax brackets.

The downside to installment sales, however, is that, being essentially a loan from the seller to the buyer of the business, the seller takes on the risk that the buyer may ultimately be unable to make their payments as required by the installment note. Additionally, it can sometimes be difficult for a business seller to even find a buyer who is willing to agree with them on the terms of an installment note. And furthermore, because an installment sale involves one or more payments being deferred until future years, the seller can't use or invest any of the sales proceeds until they're actually received.

One purported solution to the issues with installment sales that has been promoted by a group of accountants, attorneys, and financial advisors is known as a Deferred Sales Trust (DST), which works by using a third-party (the trust itself) to buy a business or other asset from the seller under an installment agreement, rather than selling directly to the ultimate buyer. The trust then sells the asset to the buyer in a lump-sum transaction and invests the proceeds to pay back the seller under the terms of the installment agreement. As the sales pitch goes, this allows the seller to benefit from installment sale treatment, while eliminating the credit risk of selling to a buyer and giving them at least some ability to choose how the proceeds are invested even before they actually receive them.

However, closer scrutiny of the DST strategy raises significant red flags that aren't included in the sales pitch. For one thing, details of the strategy are kept closely under wraps by the group that promotes and sells DSTs, limiting advisors' ability to vet the DST's legitimacy. Additionally, although DST promoters tout the strategy's ability to eliminate the credit risk of entering an installment agreement directly with a buyer, in reality, the risk is simply shifted to the trust itself: Because the seller cannot be the owner, trustee, or beneficiary of the DST (because doing so would cause the transaction to lose its installment treatment), they are wholly reliant on the trust to be able to make its required installment payments. Meaning that, for example, if the DST trustee mismanaged the sales proceeds and caused them to default on the installment loan, the seller would have no recourse to recover those funds. (While at the same time, any extra funds that are left over after the note is fully paid off go to the DST trustee, not the business seller – a true 'heads I win, tails you lose' proposition.)

In other words, the characteristic that is needed to make DSTs work from a tax perspective – the ceding of all control over the sales proceeds to a third-party trustee – can make them even more risky than a traditional 2-party installment sale. Which is why instead, sellers of small businesses may want to consider other strategies such as structured installment sales (in which the installment note is funded by a large insurance company that has significantly more assets with which to pay off the loan), entering into the installment agreement directly with the buyer, or even simply selling as a lump-sum and taking the entire tax hit in 1 year – which, while being possibly less favorable from a tax perspective, at least ensures that the seller receives all of the sales proceeds to begin with!

For many business owners, the firm that they own is not only their primary source of income, it's also their biggest retirement asset. While employees of companies contribute to 401(k) plans, IRAs, and other accounts over the years to build up sufficient savings for retirement, business owners often use those savings dollars to reinvest in growing their firms over time, with the eventual goal that when it's time to retire, the business can be sold and converted into more liquid assets for the seller to draw on in their retirement years.

The problem for business owners is that selling a business is a taxable event. When a person sells property that has appreciated in value, which includes everything from private businesses to real estate to shares of stock, artwork, etc., they need to pay capital gains tax on the amount of appreciation (i.e., the asset's selling price minus the owner's tax basis). And no matter the type of asset, that capital gains tax is generally owed for the tax year in which the sale actually happened: Just as selling a mutual fund at a gain in 2024 is reported on a 2024 tax return, selling an entire business in 2024 will also be included on the seller's tax return for 2024.

While there are some exceptions to this rule (e.g., sales of assets in tax-deferred accounts like 401(k) plans and HSAs, 1031 exchanges of qualified real estate property, and Qualified Opportunity Funds as established by the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act), they rarely apply to the sale of private businesses. Most of the time, when someone sells a business that they founded and actively managed, it's a taxable event in the year of the sale.

Consequently, the amount of business sale proceeds that end up being paid out as taxes can be quite significant. The combination of a high selling price and a low tax basis for the business can lead to a one-time spike in income for the seller – and because the U.S.'s progressive tax system taxes higher incremental income at higher rates, the result of selling a business might be paying the highest possible tax rates on much of the capital gains income from the sale.

Example 1: Jane runs an accounting firm that she purchased for $250,000 20 years ago. This year, she plans to sell the firm for $1 million. Assuming that her tax basis in the firm is still $250,000, then $750,000 of the sales proceeds will be taxed as capital gains income.

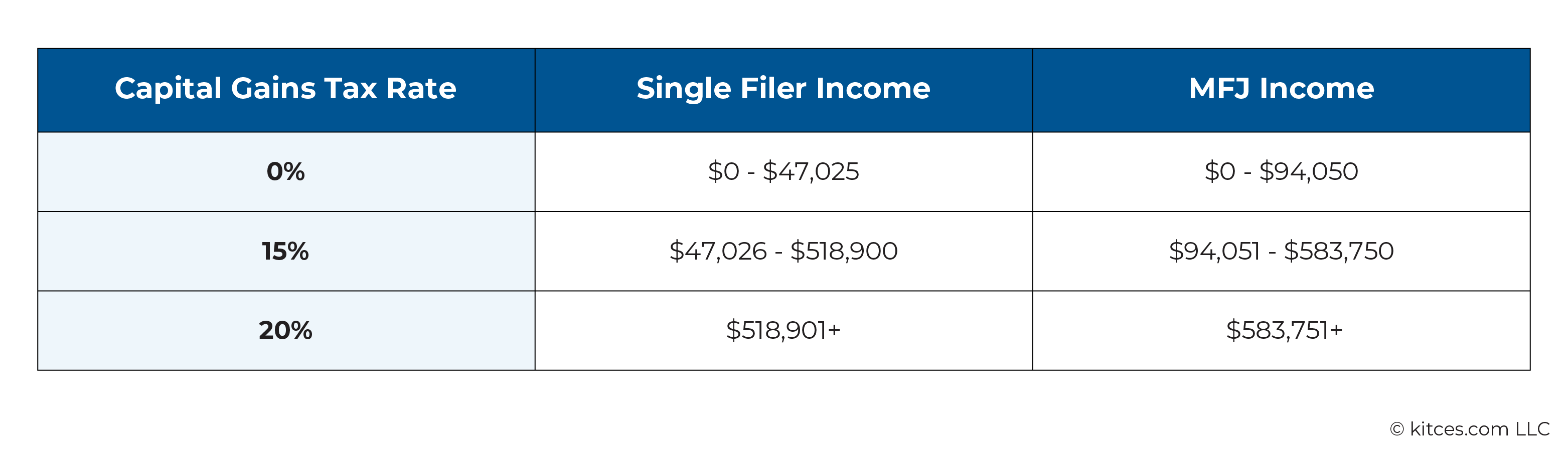

The capital gains tax brackets for 2024 are as follows:

Assuming Jane is a single filer, all of the taxable capital gains income over $518,900 will be taxed at the top Federal capital gains tax rate of 20% (plus any additional state tax).

Although an additional 5% in taxes (the result of going from a 15% to a 20% tax rate) might not seem like a lot, it does matter when – as is often the case with small business owners – the business's value makes up the bulk of its owner's net worth, which means that the net proceeds of the sale constitute most of what the seller will have to live on during retirement. Paying 5% more in taxes on the sale of the business might be the equivalent of withdrawing an entire additional year's worth of spending from the seller's retirement savings, which could have a material impact on the sustainability of their long-term plan (particularly during a down market cycle when withdrawing additional funds removes fuel from the portfolio that could otherwise help it recover when markets turn back upward).

So there's a desire among business owners for ways to reduce their tax burden upon selling their business by lowering their tax rate and/or by deferring their tax liability until a later date so it doesn't have such an outsized upfront impact on their retirement finances.

Installment Sale Rules

One option that can be available for people who want to defer at least some of the capital gains taxes from selling a business is to use an installment sale. Simply put, an installment sale is any sale of property in which the payments from the buyer to the seller are spread out over more than one calendar year.

Under IRC Sec. 453, when certain property is sold under an installment sale (including private businesses and real estate, but notably excluding publicly traded stocks and bonds), the capital gains taxes on the sale are deferred until the seller actually receives the payments from the buyer, rather than being recognized entirely in the year of the sale.

In other words, instead of one big capital gains hit in the year of the sale that can potentially move the seller up into a higher tax bracket, an installment sale allows the seller to incur a series of smaller capital gains bumps spread out over a number of years – which, if timed properly, can ensure that all of the sales proceeds are taxed in the lower capital gains brackets.

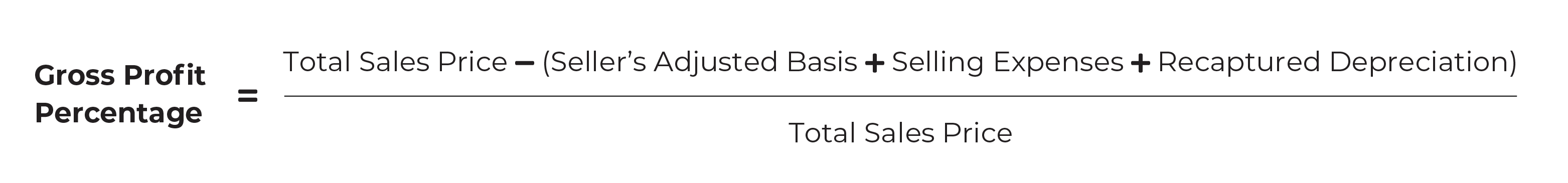

To fully grasp the potential benefits of installment sales, it's important to understand how they're taxed to business sellers. The payments received by the seller in each year of an installment plan are broken into 3 parts, each of which is taxed in its own way.

- The interest portion is either a stated interest amount specified in the installment agreement between the buyer and the seller or an amount calculated based on the Applicable Federal Rate (AFR). The interest portion is generally taxed at ordinary income tax rates.

- The portion that's taxed as capital gain is calculated as the "Gross Profit Percentage" of the sale (i.e., the total sales price minus the sum of the seller's adjusted basis, any selling expenses, and any recaptured depreciation, divided by the total sales price) multiplied by the non-interest portion of the payments.

- The remaining portion of the year's payment is considered a tax-free return of basis.

In other words, as shown below, each payment of an installment sale keeps the same proportion of capital gains to return of basis as would be the case for a traditional lump-sum sale – and the greater the number of installment payments (and the smaller the amount of each payment), the smaller the tax impact of each individual installment.

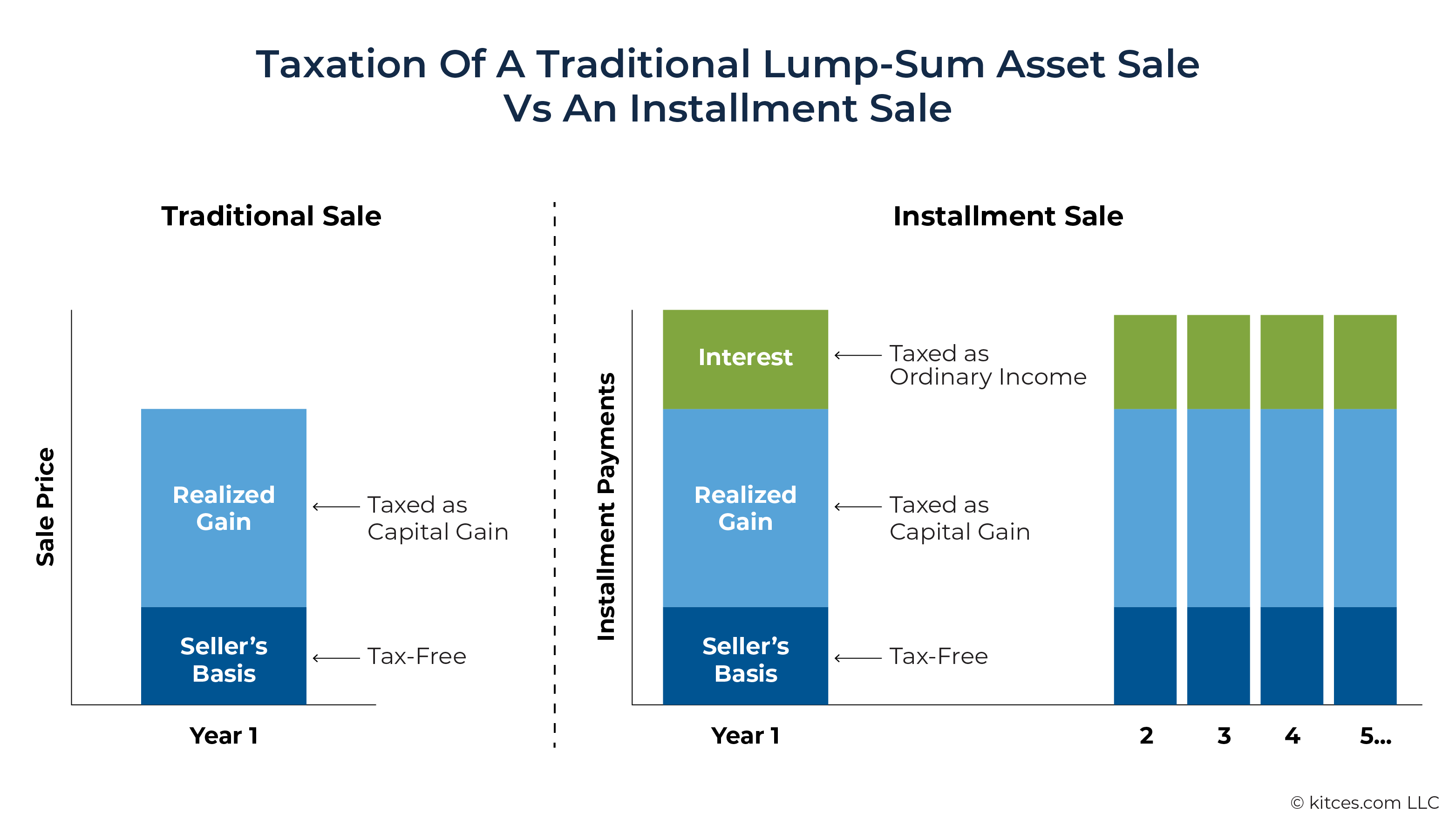

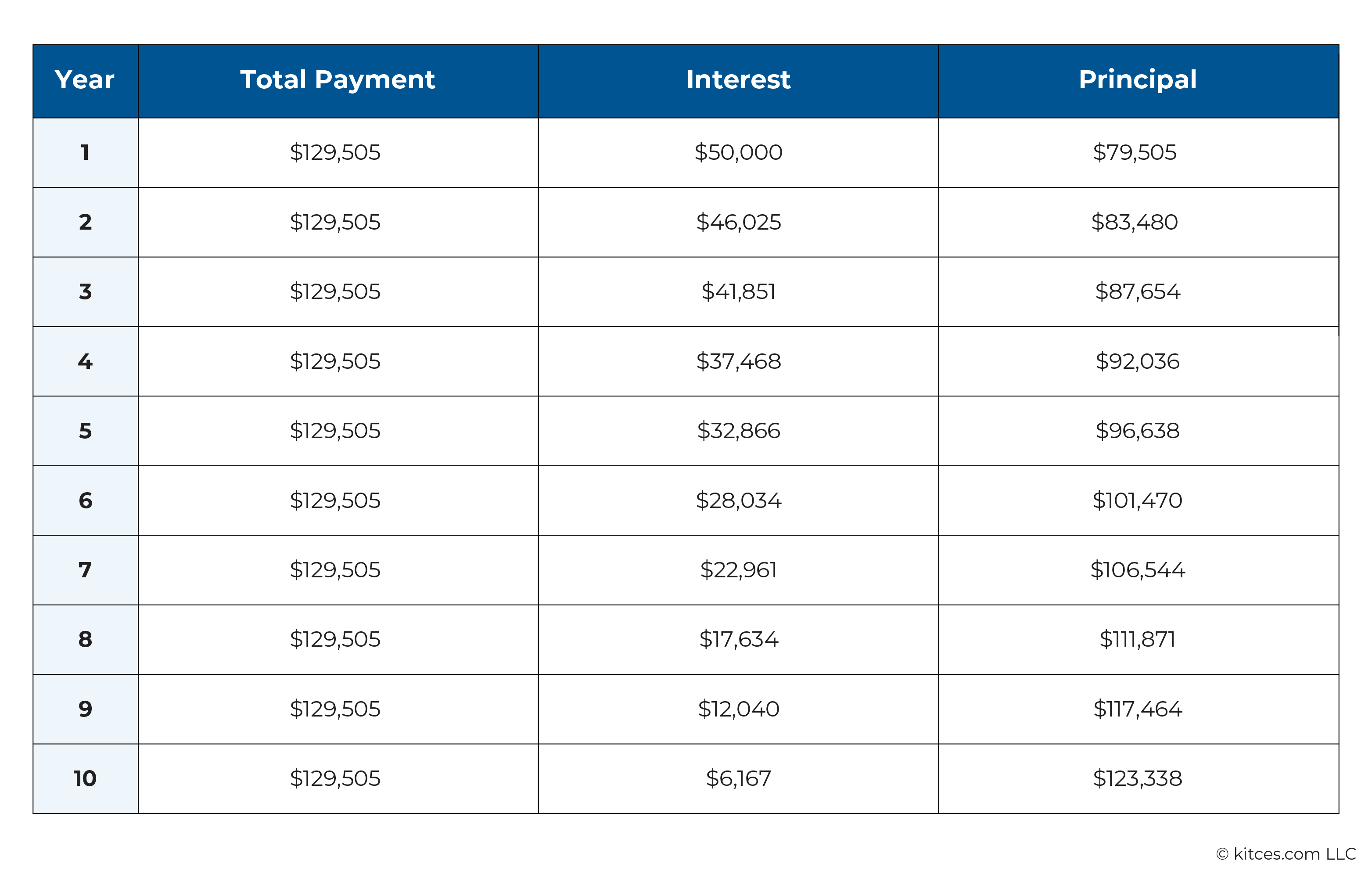

Example 2: Tina is selling her business, which she originally bought for $250,000, to Norm for $1 million. They agree to a 10-year installment sale with a 5% interest rate on the installment loan, with Norm paying Tina in 10 equal yearly payments.

In order for Tina to understand how she will be taxed on the installment payments, she needs to determine the interest and principal amounts of each payment, and then calculate how much of the principal portion of each payment consists of capital gains versus return of basis. A Time Value of Money (TVM) calculation (PV = $1,000,000, I = 5%, n = 10) shows that each annual payment will equal $129,505.

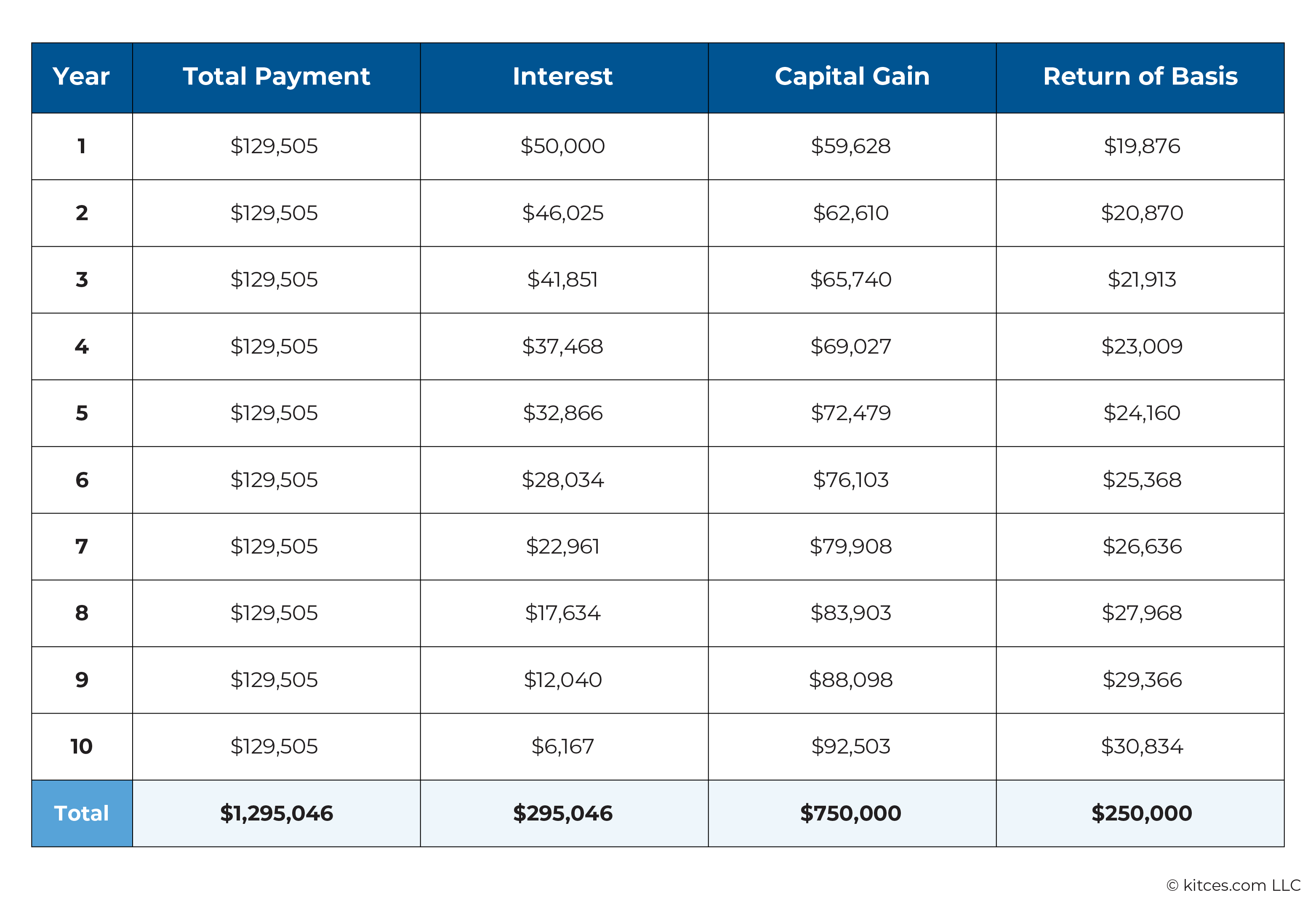

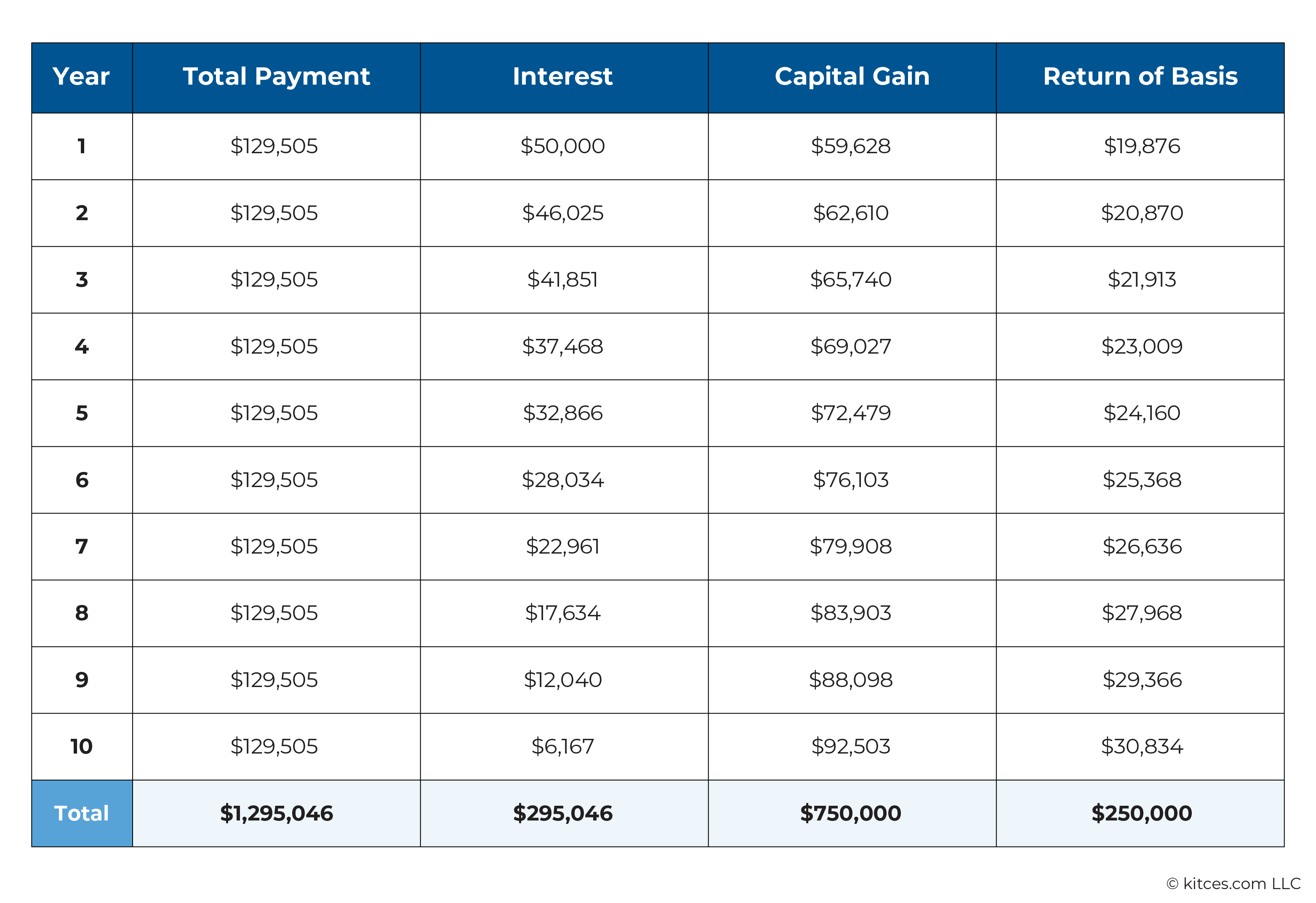

The loan amortization schedule identifies the interest and principal portions of each payment:

Interest Portion Of Loan Payment. According to the amortization schedule, in the first year of the installment agreement, Tina's loan payment will consist of $50,000 of interest. The $50,000 of interest is taxed as ordinary income. As the principal balance goes down each year, the interest portion will make up a smaller and smaller part of each payment.

Capital Gains Portion Of Loan Payment. To figure out how much of each payment is taxed as capital gains, Tina multiplies the principal portion of the payment by the Gross Profit Percentage on the sale, which is ($1 million [the sales price] − $250,000 [the seller's basis]) ÷ $1 million [the sales price] = 75%.

So for the first installment payment, $79,505 (the principal portion of the Year 1 loan payment) × 75% (the Gross Profit Percentage) = $59,628 is taxed as capital gain.

Tax-Free Return Of Basis. The remainder of the Year 1 principal payment is $79,505 − $59,628 = $19,876, which is a tax-free return of basis.

In other words, Tina's first year's payment breaks down as:

- $50,000 – Interest (taxable as ordinary income)

- $59,628 – Capital gain (taxable as capital gains income)

- $19,876 – Return of basis (tax-free)

These numbers need to be recalculated for each year of the payment schedule, as the loan amortizes and the interest and principal portion of each payment shifts. In each year, however, the amount taxed as capital gains equals 75% of the principal portion of the payment, since the Gross Profit Percentage doesn't change over the life of the agreement.

Consequently, the yearly breakdown for the installment payments into interest, capital gain, and return of basis portions would look as follows:

As shown above, the portions of the installment payments represented by capital gains and return of basis total $750,000 and $250,000, respectively – exactly what they would have totaled if the sale had been done as a single lump sum. But because the sale is spread out over 10 years rather than being concentrated in a single year, the tax consequences of the sale can be smoothed out or – as discussed in the next section – significantly reduced or even largely eliminated with the installment treatment versus a lump-sum.

Tax Benefits Of Installment Sales From Spreading Out Capital Gains Over Multiple Years

As mentioned above, the main benefit to sellers for using an installment sale is that it spreads the impact of capital gains taxes over multiple years. Selling a highly appreciated asset in a single year can result in a one-time spike in capital gains income large enough to bump the seller into a higher capital gains tax bracket, which could mean increasing to 15% or 20% (with an additional 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax for investment income over $200,000 for single filers and $250,000 for married couples).

If the seller can instead spread out the gains over a number of years in a way that keeps them in the lower brackets, they can end up paying lower taxes overall on the sale than if they had taken the entire tax hit in a single year.

Example 3: Tina, from the example above, is married and will have no other income this year other than from the $1 million sale of her business (cost basis = $250,000) to Norm. In deciding whether to sell her business all at once in 2024 or to use an installment sale over 10 years, she considers the outcomes of each scenario.

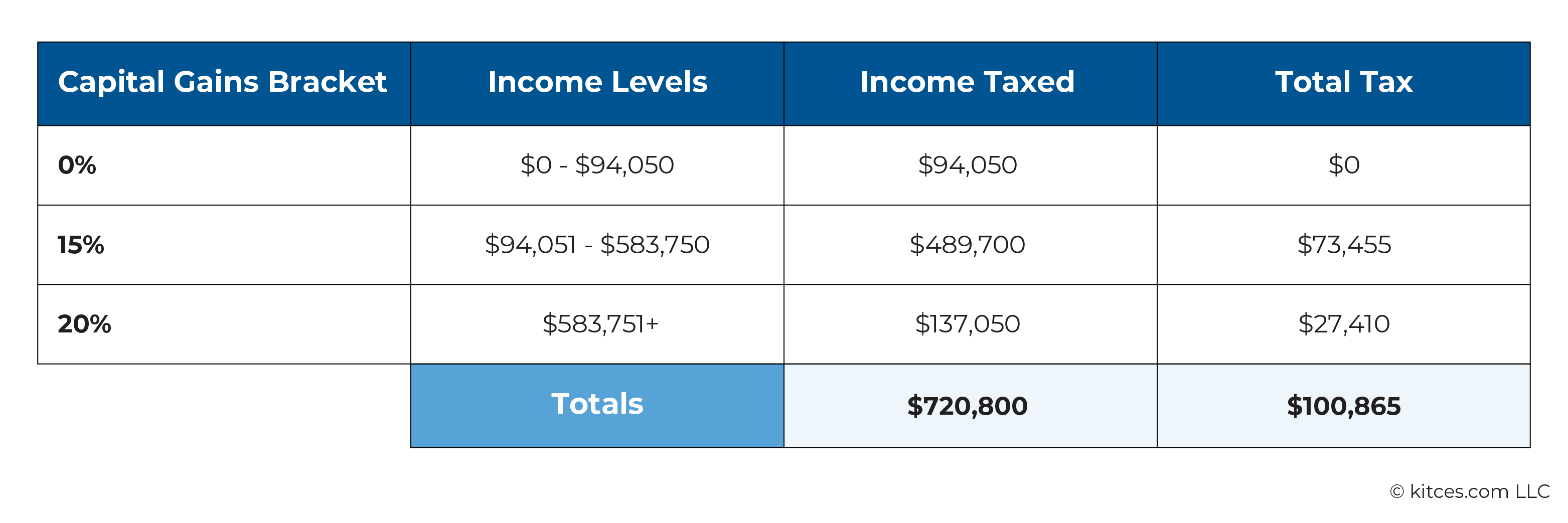

Lump-Sum Sale Scenario. If Tina were to sell her business and receive 100% of the sales proceeds this year in 2024, she would need to recognize all $1,000,000 – $250,000 = $750,000 in capital gains income, which would mean her total taxable income for the year would be $750,000 (capital gains income) − $29,200 (the 2024 standard deduction for married filers) = $720,800.

Since 100% of Tina's taxable income comes from capital gains, it would all be taxed at capital gains rates, which would break down as follows:

Additionally, the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) would apply on the capital gains income over $250,000, meaning that in addition to the $100,865 in regular capital gains tax, Tina would also owe 3.8% × ($750,000 – $250,000) = $19,000 in NIIT, which would bring the total Federal tax on the sale to $100,865 + $19,000 = 119,865 (plus any state taxes owed).

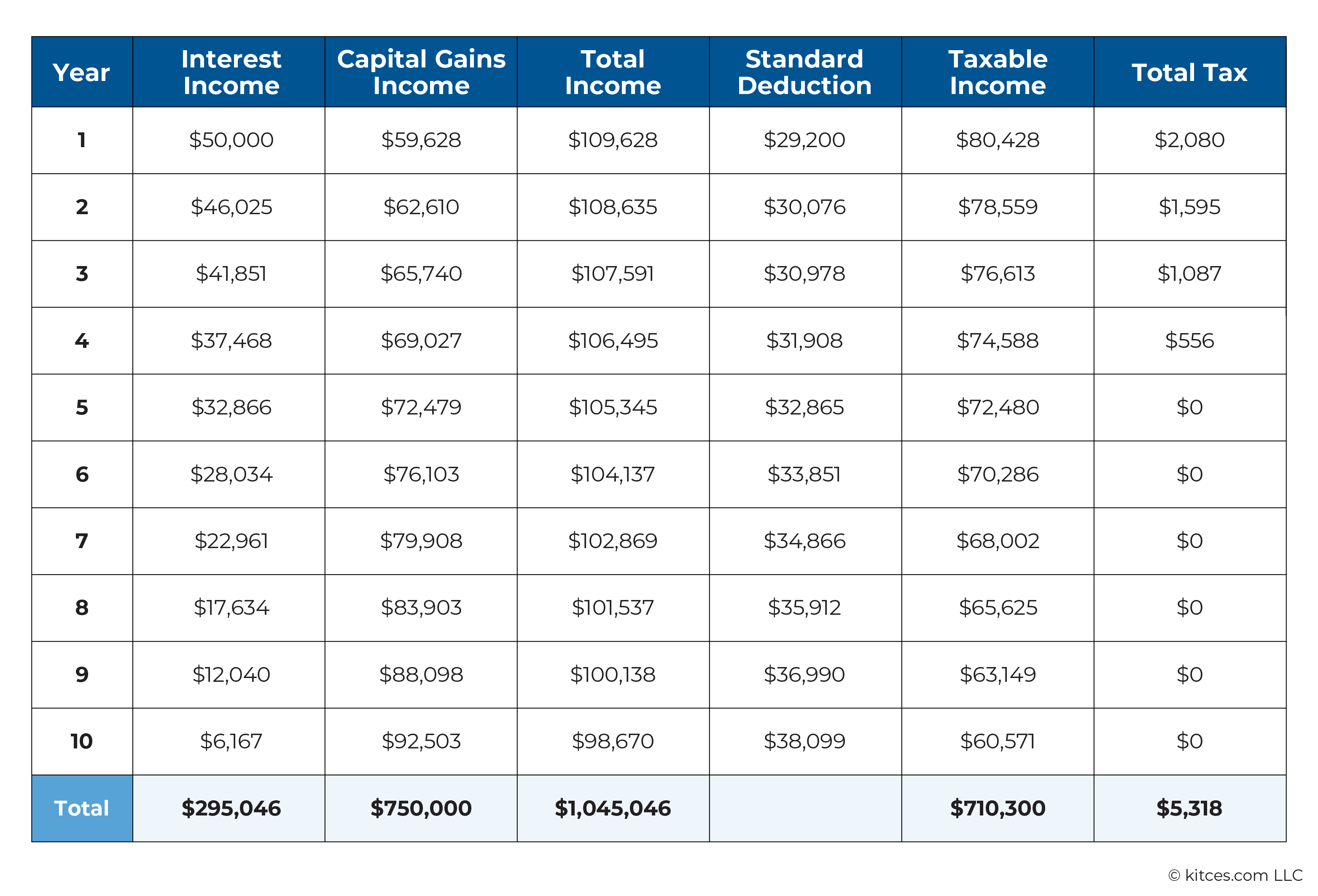

Installment Sale Scenario. Instead of receiving 100% of the sales proceeds this year, Tina considers the following 10-year installment schedule at 5% interest (as shown in Example 1 earlier):

Assuming the tax brackets and standard deduction grow at 3% per year, Tina's taxes on the installment payments each year would break down as follows, with interest income subject to ordinary income tax rates, and capital gains subject to 0% capital gains tax (since Tina's income levels under this scenario allow her to remain in the 0% capital gains bracket each year, as discussed further, below):

Notably, even though the installment method actually adds $295,046 to the total amount of taxable income Tina recognizes over the life of the sale in the form of the interest portion of each payment (compared to recognizing 'only' the $750,000 of capital gains income from the lump-sum sale), the way the income is distributed results in a much lower tax bill than in a lump-sum sale: After year 4, each year's interest income is more than offset by the standard deduction.

Meanwhile, the effect of spreading out the capital gains over 10 years means that instead of being taxed at a mix of 0%, 15%, and 20% tax rates, all of the capital gains income is taxed at 0%, and because Tina's income never exceeds the $250,000 NIIT threshold, the 3.8% NIIT never applies either.

Ultimately, the tax impact of Tina's decision to sell her business using an installment sale is the difference between the $119,865 in Federal taxes when recognizing the entire sale in one year versus $5,318 in total taxes over the 10 years under the installment agreement, which amounts to $114,547 in Federal tax savings!

The tax benefits of the installment sale might not be quite so stark if the seller has other income that would push them out of the 0% capital gains tax bracket, but ultimately most installment sales should result in at least somewhat lower taxes compared to a lump-sum sale by shifting more of the capital gains income from the 15% and 20% capital gains tax brackets into the 0% and 15% brackets (and potentially reducing or eliminating the amount subject to NIIT).

Downsides Of Installment Sales

The substantial tax savings that can be realized by using an installment sale, especially on a valuable and highly appreciated asset like a business, can make it very desirable as a planning tool. However, taxes aren't the only factor that need to be considered when deciding whether to use an installment sale.

The first consideration is that an installment sale is effectively a loan from the seller of a business to the buyer, which means that the seller needs to have some assurance that the buyer can actually make the required payments over time. Most of the time, installment sale payments for a business sale are made from the ongoing cash flows of the business in the hands of the buyer; if there's a business downturn, or if the buyer simply doesn't run the business as effectively as the previous owner did, that cash might not be available to make the required payments, and the buyer will default on the installment loan.

Additionally, while the business itself may be used as security for the payment (meaning it can be repossessed if the buyer defaults on their installment obligations), reacquiring and then reselling the business is a significant hassle for someone whose intent was not to be actively involved in business ownership anymore. Taking on the credit risk of the buyer, then, may ultimately make sellers uneasy if their goal is to step away from the business and be free from worrying about its day-to-day operations.

Furthermore, the reality of business sales is that they take 2 willing parties – the buyer and the seller – to complete, and both parties tend to have their own goals and preferences. The terms of an installment agreement (e.g., the length of the agreement, the payment schedule, or the interest rate) that might be ideal for a seller might be less so for a buyer and vice versa, and if the buyer and seller can't come close enough in their demands to reach an agreement, there might simply be no possibility for an installment agreement that makes both sides happy. An installment agreement is only a possibility if there is actually an agreement.

Perhaps the biggest downside of an installment agreement from the seller's perspective is that in contrast to a lump-sum sale, where the full sales proceeds are transferred to the seller at closing, an installment agreement doesn't provide the seller with access to those funds right away. The IRS is quite clear that for the seller, any "constructive receipt" of sales proceeds will result in those proceeds being taxed in that year. Meaning, that the seller can't, for example, ask a third party to give them a loan against the full amount of the sales proceeds, which they pay back as they receive payments from the buyer over time, without losing the installment treatment for tax purposes (i.e., a "monetized installment sale" that the IRS has flagged as a potentially abusive tax transaction for evading or avoiding tax). Some sellers might actually prefer to complete the sale all at once, even if doing so means paying more taxes, because they can then immediately use or invest the remaining sales proceeds rather than waiting 5–10 years or more to receive all of the payments from the sale.

In other words, even though installment treatment of a business sale can result in significant tax savings (e.g., more than $100,000 in the examples above), it still only really makes sense to enter into an installment agreement when 1) there's assurance that the buyer can make the installment payments; 2) the buyer and seller can agree on an installment schedule that works for both parties; and 3) the seller doesn't mind waiting a year or more before they actually receive the proceeds of the sale.

The Deferred Sales Trust Pitch: The Benefits Of Installment Sales Without The Hassle

In recent years, a network of financial advisors, accountants, and attorneys, collectively known as Estate Planning Team has promoted a strategy that they've dubbed the Deferred Sales Trust (DST). In a nutshell, DSTs are generally pitched as a way to sell an asset like a business or real estate property and defer taxes on the proceeds with Sec. 453 installment treatment, while also having a greater degree of control over the terms and structure of the installment agreement and the ability to invest the full sales proceeds before being actually taxed on them.

In other words, per its promoters, DSTs have all of the benefits of installment sales via deferring and spreading out taxes over time, with none of the downsides of taking on credit risk, negotiating payment terms, and waiting on sales proceeds – effectively providing a way to have your cake and eat it too when it comes to installment sales.

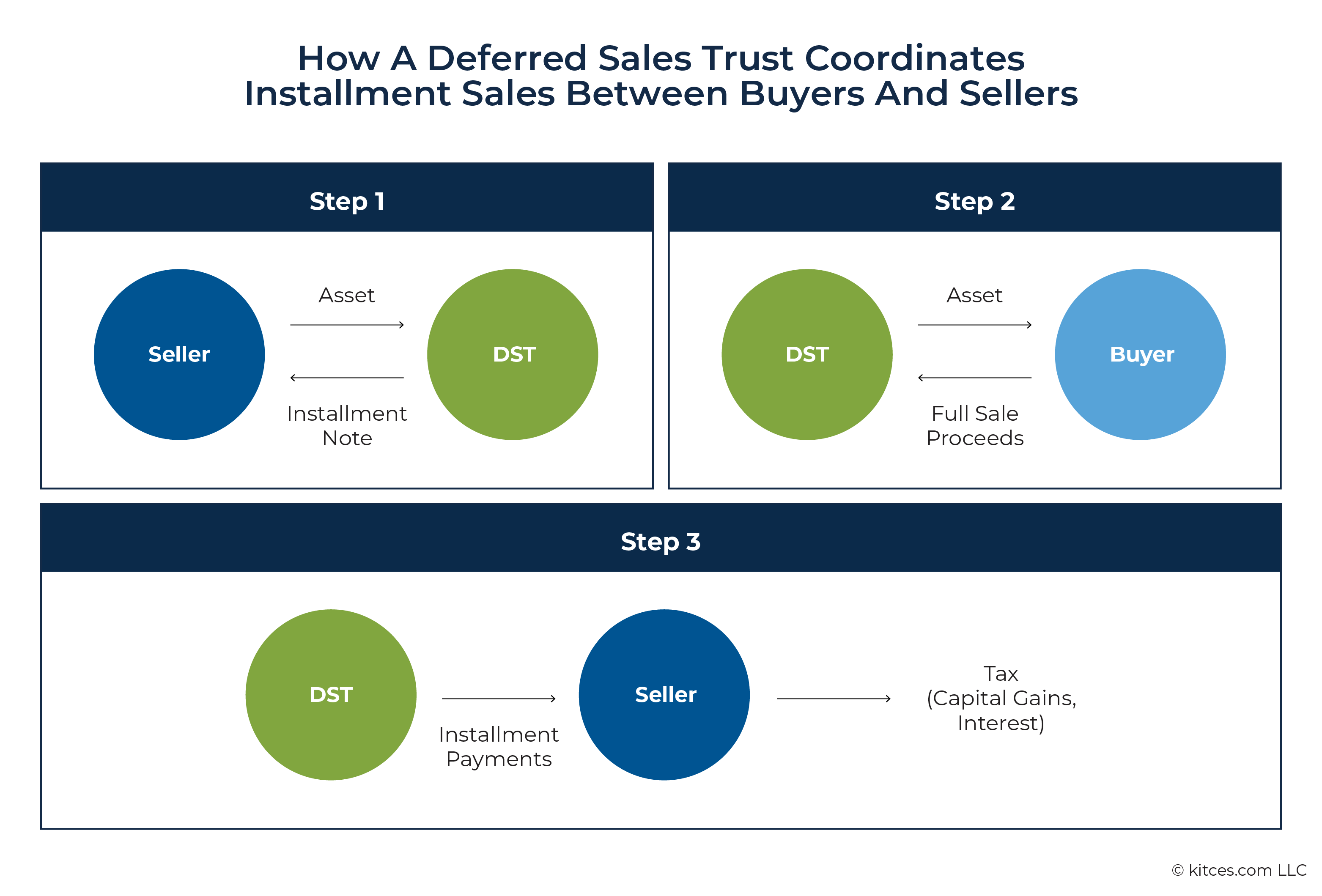

More specifically, DSTs work by routing the sale of the asset through a third party – the trust – rather than directly between the buyer and the seller as with a traditional sale. The process can be broadly broken down into 3 steps, starting after the buyer and seller have agreed on a sales price for the asset being sold:

- First, the seller sells the asset to an irrevocable trust in exchange for an installment note (i.e., a loan) representing the sales price of the asset spread out over a certain period of years plus a predetermined interest rate.

- Next, the trust sells the asset to the buyer in a lump-sum sale for the already agreed-upon sales price, with the trust receiving the full sales proceeds in a lump sum. (The buyer's involvement ends here, meaning the seller deals with only the DST going forward).

- Finally, the trust reinvests the sales proceeds as directed by the seller and makes payments to the seller over time per the terms of the installment note. The seller doesn't pay any taxes until they receive payments from the trust, which are taxed in the same way as if they had been installment payments received directly from the buyer, with different portions treated as interest, capital gains, and tax-free return of basis.

The key to this setup working from a tax perspective is that the seller never actually takes possession of the sales proceeds until they receive installment payments from the trust. That's because the seller doesn't own the trust, nor are they a trustee or beneficiary – they're simply a creditor of the DST, by virtue of having sold the asset to the trust in exchange for the installment note. However, if the seller had any kind of direct control over the trust or its assets, they would be forced to immediately recognize all the income from the sale, disallowing the installment treatment and negating any benefits of the DST itself.

That said, DST providers do seem to allow their "client" – i.e., the seller, who is typically the person who hires the DST provider in this arrangement – to have at least some say in how the trust operates, despite not having legal ownership of the trust. For example, the seller can have input into the asset allocation and investments into which the sales proceeds in the trust are reinvested, they can request changes to the installment note schedule, and they can even request to cancel the installment note entirely and receive the remainder of what they're owed. But ultimately, any of those actions are at the sole discretion of the DST's trustee, who must be completely independent of the seller and not a related party such as a spouse or relative in order to preserve the installment sale treatment of the sale.

The Problem With Using A Deferred Sales Trust To Defer Taxes On A Business Sale

It's worth noting that a Deferred Sales Trust (DST) is not a type of trust that's been recognized or sanctioned by the IRS. The term "Deferred Sales Trust" itself was actually trademarked by Estate Planning Team ("was" being the key word here – the trademark with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has been classified as Abandoned since 2021). There has been no public IRS guidance on whether DSTs are legal or compliant with tax regulations, and while its promoters make assurances that the strategy has withstood previous IRS audits with no adverse findings, there's no official IRS position that anoints it as a legitimate strategy.

What's also worth noting is that while the broad outline of the DST strategy as described above is public, the actual details of how DSTs work are proprietary to a handful of trustees, attorneys, CPAs, and advisors in the Estate Planning Team network, all of whom work to promote and sell the strategy to clients both directly as well as via accountants and financial advisors. Only those who join the network of DST promoters are let in on the full details of the strategy, and while outsiders can review it either for the purposes of considering whether to join the network or to evaluate the DST strategy on behalf of their own clients, those individuals are required to sign Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) legally barring them from describing the strategy's details in public.

In other words, DST is more of a product than an established tax planning strategy, and only attorneys, advisors, and accountants who are actually involved in selling and administering DSTs can truly be experts in it (and everyone else who knows all of the details is legally prohibited from discussing them in public). And so while none of this means that DSTs can't necessarily be legitimate from a tax perspective, it's impossible to know for sure without public IRS guidance or objective third-party analysis. Which might make it difficult to recommend them as a financial advisor, since giving advice on tax strategies that fall outside the well-defined boundaries of current tax law is something that could constitute the kind of "Tax Advice" that's the purview of credentialed tax professionals like CPAs, EAs, and attorneys.

There are other concerns about DSTs that stem from the structure of the DST itself. A 2020 filing from the Washington State Department of Financial Institutions charging a DST trustee and associated accountants and financial advisors with violating state securities laws for offering DSTs without being registered in the state, as well as perpetrating fraud by implementing a DST for a client without a valid installment note in place, illustrates a number of the risks inherent in DSTs that don't tend to be emphasized in the sales pitch.

As mentioned above, the DST cannot be owned by the business seller themselves, nor can the seller serve as trustee or beneficiary of the trust. Instead, as the Washington State filing states, "the trustee is both the trustee and beneficiary of the trust, and maintains full legal control over the trust and the assets therein". Which leads to one of the main concerns for the seller, because once they sell their business to the DST, and the DST sells it to the eventual buyer, the seller no longer owns any of the sales proceeds (other than whatever amount they choose to receive – and be taxed on – upfront). All they 'own' is the note from the DST, obliging the DST to make the required payments to eventually pay the agreed-upon sales price plus interest.

What happens next is that the DST reinvests the business sale proceeds, ostensibly in a way that best allows it to pay off the installment note. But if the terms of the installment note are fixed (e.g., 10 years of payments at 5% interest) and the investments vary in value as all investments do, it's almost never going to be the case that the amount of sales proceeds in the DST will be exactly enough to pay off the installment note. There will either be something left at the end after all the installment payments are paid, or there will be a shortfall in funds that will mean the DST can't fulfill its obligations.

What happens then? As the Washington State filing puts it:>

If the investments perform poorly and the trust's assets are depleted before it has made all of the payments on the note, the trust is not obligated to make any additional payments. Conversely, if the investments perform well and the trust is able to make all of the payments on the note, the trustee keeps any funds left over after the payments are made. The DST investor has little or no control over the success of the note, and is mostly or entirely dependent on [the trustee] to manage the trust appropriately, and on [the financial advisor] to make appropriate investment recommendations.

In other words, for the DST trustee, it's a 'heads I win, tails you lose' situation. If the investments in the DST underperform expectations, resulting in the sales proceeds being depleted before the DST can pay off the installment note, there's no recourse for the seller to recover the rest of the funds that they're owed: Since the trust doesn't own any assets other than the sales proceeds, there's nothing that can be seized or repossessed in the event of a default on the installment obligations (unlike a traditional 2-party installment sale, where the seller can potentially repossess the asset that they originally sold, or sue the buyer personally to try to recover from their other assets).

Furthermore, as a matter of law, trustees are generally not personally liable for a trust's debts unless they breached their fiduciary duty to the trust (and importantly, it's the trust to whom the DST trustee has a fiduciary duty, not the "client" with whom the DST entered into the installment agreement), so the seller would have no recourse to sue the DST trustee if it wasn't able to pay off the installment note. Put more simply, if there's nothing left in the DST, and the business seller is still owed payments on their installment note, they're just plain out of luck.

On the flip side, in the event of excess funds, anything left over in the DST once the installment payments are completed goes to the DST's beneficiary, which is also the DST trustee. The only legal obligation that the DST has to the seller is for the payments outlined in the installment note, and so when those payments are complete, any remaining assets – despite originating from the original sale of the business – are legally the property of the DST trustee. Which incentivizes the people administering the DST to take more risk with the DST's investments than would be necessary to pay off the installment note, since they can keep any of the extra income it generates (while not incurring any extra liability for the losses it may produce).

In other words, all of the benefits that come from the DST investments overperforming go entirely to the DST trustee, while all of the risk of the assets underperforming is incurred entirely by the seller.

And so although DSTs are often pitched as a way to take advantage of installment treatment and deferring tax without taking on the buyer's credit risk, in reality, using a DST simply shifts that credit risk from the buyer to the DST and, effectively, its trustee. And because there's almost zero legal recourse for the seller in the event the DST trustee mismanages its investments or depletes its assets before the installment note is paid off, DSTs are arguably more risky than a traditional 2-party installment sale, where there's at least some possibility of the seller being made whole.

So Are The Benefits Of DSTs Really Worth The Risks?

While the sales pitch for DSTs often makes it seem like sellers of businesses and other highly appreciated assets can get the best of both worlds – tax deferral on the one hand, and minimal credit risk/maximum control over the sales proceeds on the other – the reality is that it's impossible to have both of those things at the same time. In order for the seller to receive installment treatment for the sale under Sec. 453, they can't have any direct control over the deferred sale proceeds and are essentially dependent on the trustee's ability to manage the investments responsibly and pay off the installment note. And if the seller actually wants to have unimpeded control over the sales proceeds, they need to recognize (and be taxed) on the income from the sale.

The sales pitch for DSTs works because people dislike taxes in general, and the 'case studies' promoted by DST sellers often paint unrealistically favorable scenarios in which the taxes on a multimillion-dollar asset are eliminated entirely through the magic of a DST. In reality, of course, the taxes are simply deferred rather than vanishing entirely, and certain taxes might not be eligible to be deferred at all: For instance, any part of the gain on the sale that represents recaptured depreciation under Sec. 1245 or 1250 (i.e., business or real estate property that has been depreciated over time) doesn't qualify for installment treatment and needs to be recognized entirely in the year of the sale, while Sec. 453A requires taxpayers with over $5 million in outstanding installment obligations to pay interest on their deferred tax liabilities to the IRS. Which means that for an asset where much of the gain comes from previously taken depreciation (which may be the case with many rental properties), or where the asset's sales price is over $5 million, the installment sale benefits promised by DST promoters may not be as great as advertised.

It's also worth noting that there can be other ways besides using a DST to defer taxes on the sale of a highly appreciated asset. For real estate property, DSTs are often touted as a backup plan for a 1031 exchange for situations when a suitable replacement property can't be found within the required 45-day window, but there are other investments out there, such as Delaware Statutory Trusts (yes, another kind of DST, but different from a Deferred Sales Trust) that qualify as replacement property for 1031 exchanges and have the benefit of being a legally recognized type of trust rather than a proprietary product whose details are kept secret from everyone except the people who actually sell the product.

For owners of businesses and other assets, a Structured Installment Sale works similarly to a DST in that it uses a third party to facilitate the installment agreement between the buyer and the seller, except that the third party uses the sales proceeds to fund an annuity that pays the installment note in the form of period-certain annuity payments, which greatly reduces the credit risk assumed by the seller since the annuity can be purchased from a large and reputable insurance company (as compared to a DST where the trust's ability to make the installment payments is highly dependent on the skill of a single investment manager).

Even though there are cases where a DST-facilitated installment sale might provide the opportunity to save taxes for the seller of a highly appreciated asset by spreading out the capital gain over multiple years, it's crucial to weigh those benefits – the actual benefits as calculated with the client's own circumstances in mind, not the rosy assumptions used in the DST's sales pitch that might overstate the amount of tax that can be deferred or the overall tax savings – against the risk involved in signing legal title to a substantial amount of assets over to a DST trustee. Although projected tax benefits can make for a powerful sales pitch, it's better for the business seller to be assured that they'll actually receive the agreed-on price for the business that they worked hard to build and sell!