Executive Summary

In the modern era of financial advice, the advicer/client relationship is tightly centered on trust. And because of that foundation of trust, in an ideal advisor/client relationship, mistakes, disagreements, and concerns are surfaced quickly; action items are agreed and acted upon by everyone involved; and everyone feels aligned and accountable to their overall objectives.

The reality, however, can be a little more complicated – not only when it comes to getting clients to ask questions, give honest feedback, and raise (productive) disagreements; but also to get everyone truly aligned on (and excited about) action items and objectives. This can be frustrating for advisors: after all, clients are paying for advice, but if they never really seem 'bought into' that advice and don't act on recommendations, it can be hard for the advisor to feel like they've provided much value to the relationship.

In his book "The Five Dysfunctions Of A Team", Patrick Lencioni discusses similar issues that commonly occur among teams in the workplace. He posits that teams can suffer from a series of 5 "dysfunctions" which inhibits a team's ability to align on objectives, act on them, and actually track and discuss the results. Dysfunction in teams can be insidious – the vast majority of people in the workplace are well-intentioned and don't intentionally sow dysfunction. However, even well-meaning people can occasionally contribute to dysfunctional relationships, teams, and company cultures.

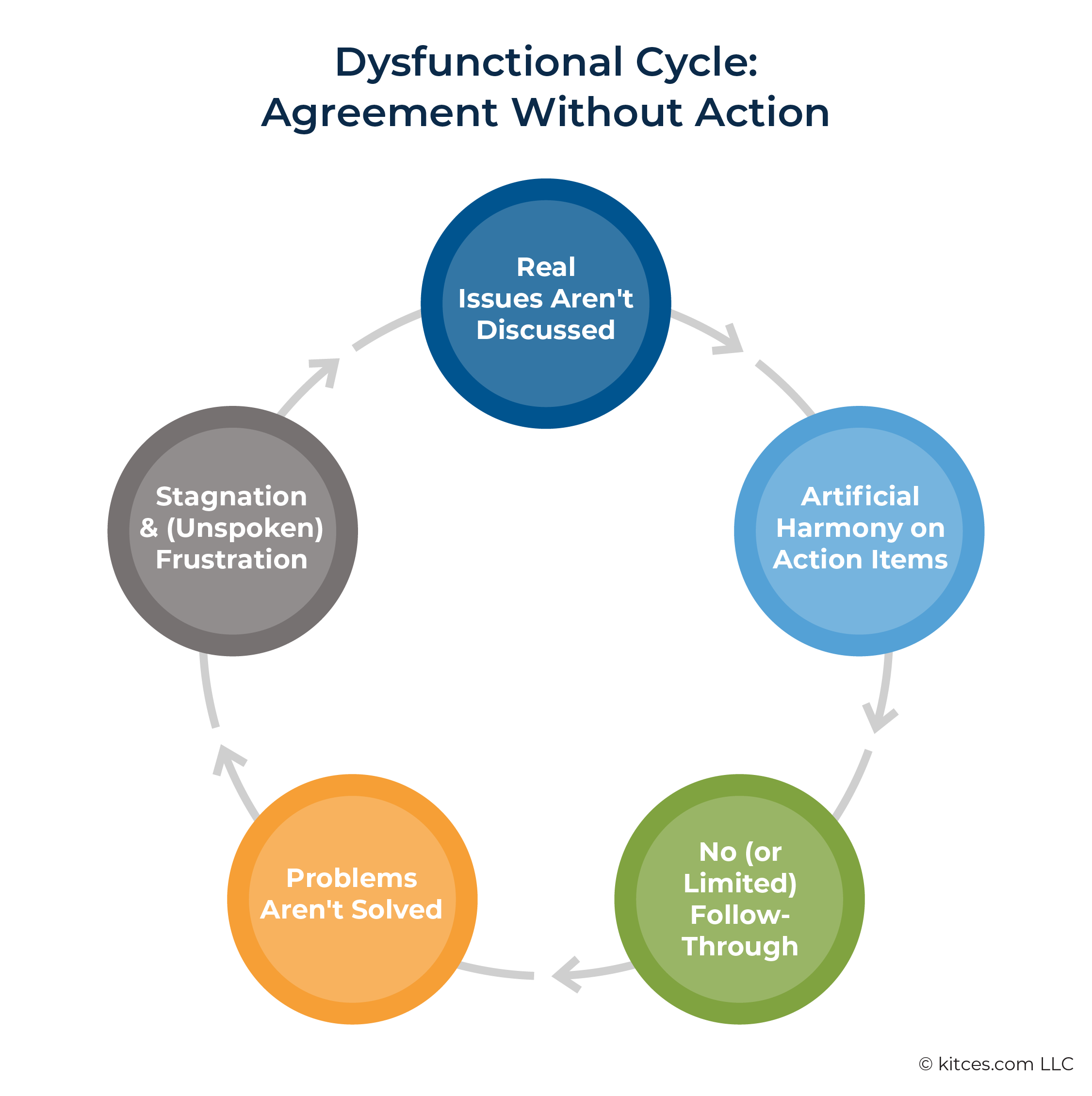

In the book, Lencioni gives insights into how dysfunction can be rooted out of a workplace – many of which can also be applied to the client/advisor relationship, where well-meaning clients and advisors can on occasion contribute to a dysfunctional relationship. As an example, a dysfunctional client/advisor relationship can look like one where the client doesn't bring forward their "true" issues to a meeting, or where they have reservations about an advisor's recommendations but feel hesitant to express them to the advisor. Then, because the client isn't "bought in" to the recommendations, they simply don't act on what the advisor recommends.

The good news is that dysfunction isn't necessarily permanent – in fact, it can be improved upon or even resolved entirely. For advisors looking to resolve dysfunction, the first action item often comes with a candid conversation with a client centered on how the client feels the relationship is going, ranging from their comfort with bringing important issues to meetings to their alignment with the advisor on action items. Once an advisor understands not only where they see dysfunction themselves, but also where their client sees it, they can begin the work of uprooting and resolving it. Depending on the situation, this can involve exercises to rebuild trust or working with clients to name how they experience and work through conflict.

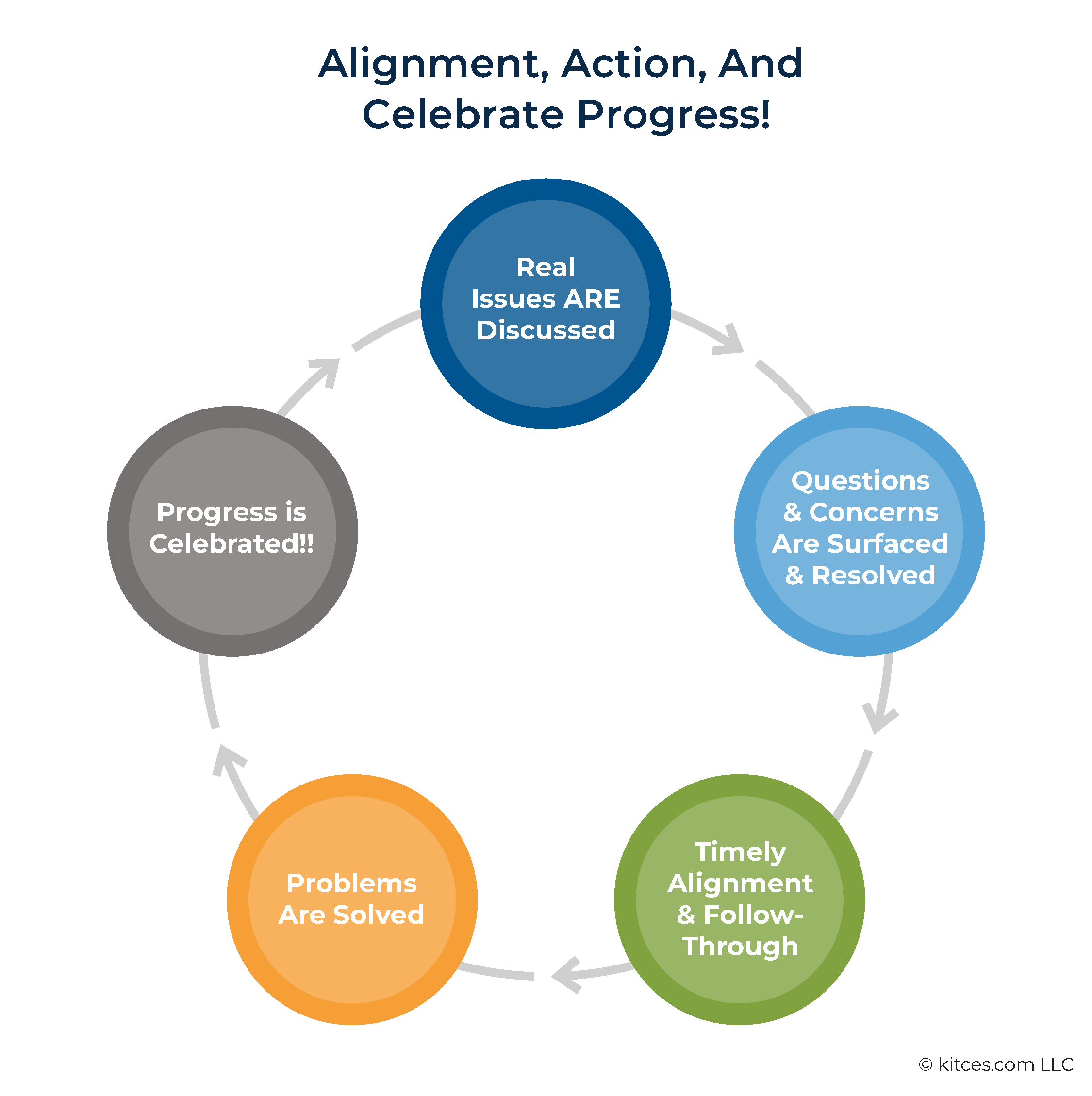

Once dysfunction in relationships is worked through and relationships become more functional, an advisor/client relationship can enter a positive feedback loop: clients bring what matters most to meetings, advisors present recommendations, reservations and questions are resolved in-meeting, everyone is aligned on what their actions are and why they matter, and implementation and results are tracked and celebrated. This then incentivizes clients to continue to bring issues forward, and reinforces an advisor's value many times over.

Ultimately, the key point is that few people intend to add dysfunction to relationships – it's something that runs the risk of creeping into client/advisor dynamics often because of good intentions. But the good news is that with proactive and mindful conversations, the advisor and client can not only resolve dysfunction, but in fact create a stronger dynamic than existed previously, where clients and advisors are constantly working through the issues that matter most!

Financial advising is a profession that requires collaboration. Whether working with a team of other advisors or relying on support from third-party providers, all financial advisors work with their clients to develop a shared vision of financial goals and then create and execute a plan to reach those goals. Advisors are often the quarterback of a client's financial life, working with attorneys, accountants, insurance brokers, and a host of other financial professionals to meet their client's needs. And while being a vital member of so many teams can lead to rich relationships and a productive practice, advisors may sometimes find themselves operating in teams that are not functioning optimally.

In his book, "The Five Dysfunctions Of A Team", Patrick Lencioni uses a parable (or comic, for a more amenable/entertaining retelling of the dysfunctions) to illustrate how some executive-level teams may appear functional to an outside observer because they have a fully staffed, experienced team that appears productive. However, those same teams may house insidious dysfunctions that make it difficult for team members to align on priorities, coordinate their deliverables, and get things done in a timely manner, which can stall progress for both individuals and the company. In other words, tasks may technically get done, but they may not be completed efficiently or in alignment with company strategy. Crucially, while a healthy team might call out this dynamic, one aspect of a dysfunctional team is that there is likely no one willing to address the things going wrong.

In his book, "The Five Dysfunctions Of A Team", Patrick Lencioni uses a parable (or comic, for a more amenable/entertaining retelling of the dysfunctions) to illustrate how some executive-level teams may appear functional to an outside observer because they have a fully staffed, experienced team that appears productive. However, those same teams may house insidious dysfunctions that make it difficult for team members to align on priorities, coordinate their deliverables, and get things done in a timely manner, which can stall progress for both individuals and the company. In other words, tasks may technically get done, but they may not be completed efficiently or in alignment with company strategy. Crucially, while a healthy team might call out this dynamic, one aspect of a dysfunctional team is that there is likely no one willing to address the things going wrong.

Similarly, the advisor and the client often act as a team, working collaboratively to help the client reach their goals. When this ‘team' is functioning well, there's a high level of trust in the relationship: the client has bought into what the advisor is saying, and they're eager to implement the advisor's recommendations.

But in other cases, the client may not seem as willing to follow through - even when, by all appearances, they seem to agree with the advisor's advice - which may be evidence of a hidden dysfunction in the client-advisor relationship. And although Lencioni's book was meant to explore dysfunction in executive-level teams, it can also offer insights on the causes of dysfunction in the client-advisor ‘team', and solutions for how to resolve that dysfunction and the problems it creates.

The 5 Dysfunctions Of A Team

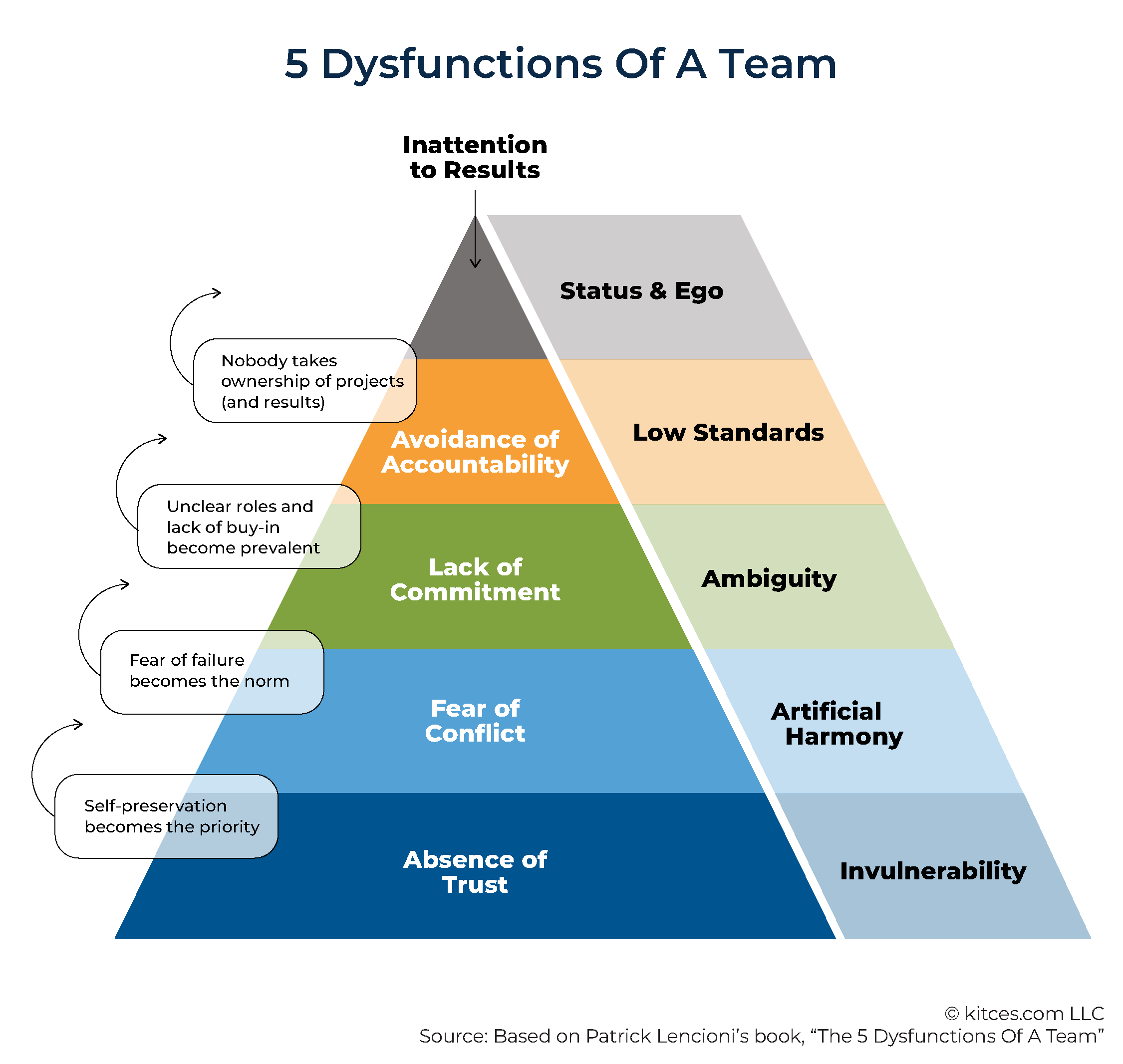

When a team is dysfunctional, it can often seem as if the problems being faced are unique. However, these issues may be the result of common behavioral pitfalls that any team could encounter, regardless of company or industry. In "The Five Dysfunctions Of A Team", Patrick Lencioni uses a pyramid structure to illustrate these common traits, as shown in the graphic adapted from the book below, noting how dysfunction begins at the 'bottom' of the pyramid and builds on itself to add on additional layers. The 5 dysfunctions, starting at the bottom, are as follows:

- Absence of Trust. Invulnerability becomes the objective when a team doesn't fundamentally trust each other and feel safe showing up as themselves. Team members become nervous about being vulnerable, showing weakness, or asking for help.

- Fear of Conflict. Where an absence of trust exists, self-preservation becomes imperative. So, team members don't dive deeply into problems or hold each other accountable for their responsibilities. This, in turn, creates artificial harmony, where teams appear to be in agreement on an issue but no one is truly 'sold' on the decision. This results in the root cause of problems never being determined or addressed.

- Lack of Commitment. Conflict-avoidant teams usually develop a fear of failure, so they have difficulty making decisions. As a result, members of the team often lack both clarity on what their team is trying to achieve and buy-in that these objectives are important.

- Avoidance of Accountability. Dysfunctional teams avoid making decisions, so no one takes true ownership of a project or directive.

- Inattention to Results. Without someone to take accountability for projects or directives, people tend to ignore – or even actively avoid – results.

The key point, as Lencioni writes, is that while dysfunction begins at the 'bottom' of the pyramid, symptoms may not visibly manifest until the dysfunction reaches the highest levels. Which makes it critical to address team dynamics that may feed into the bottom layers of absence of trust and fear of conflict, in order to fight dysfunction at a foundational level.

Dysfunction Manifests Even In Well-Meaning Teams

To demonstrate how these 5 dysfunctions may manifest, consider the following example:

Britta is VP of Marketing at Greendale Advisors, a rapidly growing RIA full of capable advisors. Due to how quickly the firm is growing and changing, every day presents a new challenge, and Britta feels pressure to demonstrate her expertise by showing up with all the answers, both to the team she leads and her peers, even – or perhaps especially – when she doesn't know the answer at the time (Dysfunction #1: Absence Of Trust).

As such, while each day is challenging, she and other executives spend their time in a lot of boring meetings, where no one truly challenges each other because challenging ideas or asking questions may slow down the growth of the firm (Dysfunction #2: Fear Of Conflict).

When she and Abed, the VP of Technology, worked together to build and launch an updated client portal, they both tried to coordinate a plan, but neither took the time to truly discuss their reservations or questions about different aspects of the project – after all, it was too urgent for them to meet their deadline to hash through these issues in full, and they felt that the other would be able to handle the problems that arose accordingly (Dysfunction #3: Lack of Commitment).

After the new client portal launched, clients began reaching out to their advisors, frustrated with the changes and with tons of questions about why they were no longer receiving updates about firm events and the state of the market. As advisors reached out to Abed for answers, he struggled to get the resources he needed from other departments to determine how to address these issues. He found himself telling clients that there simply weren't any upcoming client events and that they would receive updates via the portal when they were available.

However, Britta had no idea that clients weren't receiving updates on upcoming client events. When she checked the RSVPs for a webinar being hosted the next day, there were less than half of the participants from the previous month registered! She was mortified by this result and worried that her team would lose confidence in her.

She decided to send a follow-up email to all the clients to notify them of the event but forgot to submit the communication through the new client portal. This action increased the number of registered participants for the event but caused even more confusion for the clients about where they would now be receiving firm updates, which advisors continued to hear complaints about.

Britta and Abed never sat down to discuss their concerns about missed client communications, and they certainly didn't want to bring the conversation to the other departments – after all, everyone was trying their best, and it was better to just move on to the next thing (Dysfunction #4: Avoidance of Accountability).

Britta and Abed also never debriefed on the launch of the client portal to determine what was and wasn't working and to evaluate if the implementation was now progressing smoothly. They were both eager to put the project behind them and move on to the next thing and, if they were being honest with themselves, any attention they did pay to the client portal launch was solely through the lens of how this would reflect on their performance reviews, not how their work benefitted the firm (Dysfunction #5: Inattention to Results).

The above example illustrates how these 5 dysfunctions can affect a business and the lessons discussed below that can be learned.

(Productive) Conflict Can Benefit The Growth Of Healthy Teams

A crucial part of a functional team is that team members feel that they can show up as themselves. In a professional setting, this could manifest simply as having enough of an established sense of safety to answer a question by saying, "I don't know", or to disagree with managers or even the person who signs their paychecks. In other words, showing up as oneself doesn't need to mean that everything is in perfect harmony or that no one ever disagrees. On the contrary, a core part of a functional team is that conflict happens and that it is addressed in a healthy and productive way, where disagreement is not an indictment of a person or their hard work.

In fact, productive conflict can be beneficial when the entire team is aligned on what their objective is (e.g., to provide as much value to clients as possible) and determined to do their best work, even when they're not aligned on how to do so. Lencioni makes the point that a company that doesn't encourage (productive) conflict is often a company where meetings are boring. When everyone agrees and is alignment in a meeting, the experience may be pleasant in the moment, but if team members are actually hiding their reservations, these meetings can also be ineffective, wasting time and potentially leading the organization toward larger problems in the future.

Lack Of Conflict Creates A Lack Of Attention To Results

The flip side of a team whose members feel comfortable with productive conflict is one where no one feels that they can speak out when they see an issue that needs to be addressed. And when no one speaks out, it becomes nearly impossible to gain an honest assessment of the project or initiative the team is working to accomplish. Thus, one painful symptom of a dysfunctional team is inattention to results. Teams put themselves through an immense amount of work to develop and launch new initiatives, and if no one tracks the outcome, this disregard of the results could have disastrous consequences, such as lost revenue, clients, or talent.

Furthermore, team members may be reluctant to mention when they do notice that a company initiative has gone off-track or is not performing as intended. This is why 'boring' meetings can be a symptom of deeper dysfunction: If everyone is reluctant to disagree, meetings will seem rote and perfunctory. But when that aversion to conflict serves to gloss over parts of a project that may be going poorly, or unarticulated disagreements between team members, then those problems may not ultimately surface until it's too late to solve them. Debriefs on company initiatives, if and when they happen, can also lose their value when team members fear to articulate what went poorly during a project – or at worst, disagreements that have simmered since the beginning (but were never addressed) can surface in real-time at the debrief, which can unfortunately turn into a 'blame game' that nobody wins.

Most People Don't Intentionally Create Dysfunction, Even If They Perpetuate It

It's important to note that dysfunctional teams aren't necessarily made of bad actors or terrible leaders – in fact, Lencioni describes the 5 dysfunctions as "natural but dangerous pitfalls". Much as how the road to hell is paved with good intentions, dysfunctional teams often consist of people who want to do their best work .

Consider the earlier example of Britta and Abed at Greendale Advisors. Their team's dysfunction arose in part because Britta and Abed responded to time pressure in a fast-changing start-up environment; Britta and Abed were not intentionally attempting to create dysfunction in their organization but were well-meaning professionals who fell into common pitfalls.

Most professionals can think of times when dysfunction manifested in teams they were part of in the past, or how it may even be manifesting in their current team. However, the reality is that very few people go to work thinking, "How can I decrease how much my team members trust each other today?" A part of dysfunction is that it's insidious; rather than being deliberately created, it can sprout up like a weed without anyone realizing how it got there, and it doesn't necessarily need much cultivation to overtake a team dynamic and change it for the worse.

Another important point that Lencioni stresses is that no dysfunction exists in a vacuum – instead, dysfunctions "form an interrelated model, making susceptibility to even one of them potentially lethal for the success of a team". For example, a team may be paying great attention to its own results, where everyone is aware of problems that may be compromising the wellbeing of the company, but if there is an absence of trust (dysfunction #1), team members may be afraid to bring attention to the issues at stake and ask for the help needed to resolve any of the problems facing the company.

The good news is that while the symptoms of dysfunction are interrelated, dysfunction is not a permanent state – Lencioni's book is not his 'swan song' on dysfunctional teams and the companies they belong to. In fact, the entire point of his book is that these 5 dysfunctions can be solved as long as team members and managers are paying attention and willing to do the work to deal with them.

Dysfunction Can Exist In The Client/Advisor Relationship

While Patrick Lencioni (justifiably) focuses the bulk of the discussion in "The 5 Dysfunctions of a Team" on… well, how dysfunction rises in teams and how to identify and resolve it, these same dysfunctions can also arise in the client/advisor relationship.

Consider the following example:

Troy is a financial planner and the founder of City Firm. Joel and Annie Edison have been his clients since the firm's conception. The first few years with the Edisons were exciting as Troy onboarded them and helped with initial problem-solving and optimization, but after a few more years without any major life changes to reengage them, Troy feels that the meetings are starting to get boring: the Edisons do not seem engaged when talking about their financial goals or the effectiveness or progress of implementing their plan, and they never ask Troy any questions. Since it's been so long since he's had the opportunity to problem-solve with his clients, he feels as though the rapport he built with the Edisons has decayed.

Troy realizes that getting the Edisons to talk about upcoming life events and their role in the financial plan is like pulling teeth (Dysfunction #1: Absence Of Trust). Conversely, when issues actually are discussed, the Edisons politely agree to Troy's recommendations without mentioning any concerns they may have (Dysfunction #2: Fear Of Conflict), yet they don't take action to implement the recommendations (Dysfunction #3: Lack Of Commitment).

Troy worries that continually bringing up their lack of implementation and the impact that it is likely to have on their financial goals will just push the Edisons further away. They don't seem to want to talk about it, so he doesn't bring it up either (Dysfunction #5: Inattention To Results). At this point, Troy suspects their financial plan is veering off-track, but is afraid to look into the consequences or to mention it to his clients, because he doesn't want to lose the relationship to another advisor (Dysfunction #4: Avoidance Of Accountability).

In the example above, Troy feels locked in a negative loop: The Edisons don't bring real issues to their meetings, and when scenarios are brought up, the Edisons agree to whatever Troy thinks is best but then they don't act on his advice, which means that nothing changes and no problems are solved.

In this example, Joel and Annie Edison, Troy's clients, likely have some reservations about sharing their true opinions or other things happening in their life that they do not feel comfortable disclosing, which are preventing them from acting on their financial plan. They may also be confused about the parts of the financial plan they are responsible for implementing and the parts that Troy is responsible for implementing. However, without the safety to bring up these questions and concerns, the root of the dysfunction is unclear.

It's worth reiterating that, just as Britta and Abed in the first example didn't intentionally mean to create dysfunction in their working relationship, Troy, too, may be mystified by his clients' behavior. It's highly unlikely that the reason that the Edisons aren't bringing issues forward or acting on Troy's advice is because of maliciousness; but if they're not acting out of malice, then why aren't they collaboratively engaging with Troy? And, furthermore, how can Troy talk to them about it without pushing them further away?

Rooting Out Dysfunction In Client/Advisor Relationships

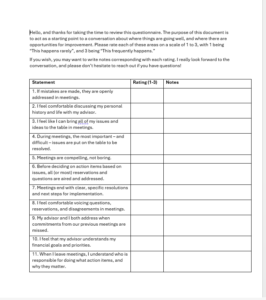

As a starting point, advisors can address dysfunction with clients by first measuring where the dysfunction (mostly) manifests. At the end of the parable illustrating the 5 dysfunctions of a team, Leonici includes an assessment to help professional teams examine dysfunctional dynamics within their own teams. Lencioni recommends scoring the questions on a scale of 1–3, where 1 represents statements that "rarely" apply (and thus suggest a higher potential for dysfunction), and 3 represents statements that "usually" apply (suggesting a lower potential for dysfunction).

The assessment items listed below are curated and adapted from Lencioni's Team Assessment to apply to financial advisors, i.e., to reflect situations that would describe a client/advisor relationship.

Questions To Measure Absence Of Trust

- As an advisor, I feel comfortable owning my weaknesses and mistakes.

- Clients are comfortable discussing their personal lives and history with me as their advisor.

Questions To Measure Fear Of Conflict

- Clients are passionate and unguarded in their discussion of issues and ideas.

- During meetings, the most important – and difficult – issues are put on the table to be resolved.

- Meetings are compelling, not boring.

Questions To Measure Lack Of Commitment

- Clients leave meetings committed to the decisions that were agreed on, even if there was initial disagreement.

- Clients and advisors end discussions with clear, specific resolutions and next steps for implementation.

Questions To Measure Avoidance Of Accountability

- Clients challenge an advisor with questions and voice disagreement in meetings when necessary.

- Clients and advisors address when commitments are missed.

Questions To Measure Inattention To Results

- Clients and advisors are both aligned on what the overall goals are and who is responsible for monitoring performance.

- Clients and advisors understand the impact of goals not being achieved.

As a pulse check, advisors may initially just want to rate these assessment statements privately for themselves, focused on how they feel things are playing out for a specific client/couple.

But ultimately, if the advisor suspects that there is dysfunction within the relationship, it may also be worth seeking the client's input as well by asking them to do their own version of the assessment with the statements adapted to reflect the relationship from the client's own point of view:

- If mistakes are made, they are openly addressed in meetings.

- I feel comfortable discussing my personal history and life with my advisor.

- I feel like I can bring all of my issues and ideas to the table in meetings.

- During meetings, the most important – and difficult – issues are put on the table to be resolved.

- Meetings are compelling, not boring.

- Before deciding on action items based on issues, all (or most) reservations and questions are aired and addressed.

- Meetings end with clear, specific resolutions and next steps for implementation.

- I feel comfortable voicing questions, reservations, and disagreements in meetings.

- My advisor and I both address when commitments from our previous meetings are missed.

- I feel that my advisor understands my financial goals and priorities.

- When I leave meetings, I understand who is responsible for doing what action items, and why they matter.

To save time in the meeting (and prevent each party from influencing each other with their responses), sending the assessment to the client to privately score in advance is usually ideal. Advisors can email the document to their clients along with a message that says something like the following:

Periodically, I like to touch base with my clients on how things are going and explore ways to enhance how we work together. Before our next meeting, keep an eye out for a questionnaire with a series of statements to assess different aspects of how we're doing. I want to emphasize: this is solely to act as a starting point to celebrate what's going well and address areas where things can be improved – especially how I can better show up for you as an advisor!

When you receive the document, you'll see a series of statements, such as, "Meetings are compelling, not boring." Please rate how frequently each scenario applies on a scale of 1-3, with 1 being "rarely" (our meetings don't feel very engaging) and 3 being "often" (most of our meetings are great!).

In our next meeting, I'll save some space for us to discuss the statements, but I won't ask for your individual rating for each item. Instead, we'll talk through what stood out to each of us, celebrate what's going well (it's always nice to know what not to change) and opportunities for improvement. I'd love to hear your honest thoughts – even and especially if there's room for improvement! There are no wrong answers here; the goal is to just explore how we can continue to work well together.

I really look forward to our conversation, and please let me know if you have any questions ahead of the call!

Notably, if a part of the root issue is that a client isn't acting on recommendations, then sending another "to do" runs the risk that the ask will not be done – advisors who are concerned about that may want to reserve some time for scoring in the meeting "just in case" in those circumstances. Alternatively, if everything seems to be going well except "that 1 thing", advisors can try paraphrasing 1 or 2 of the questions live in a meeting, such as by asking scaling questions (where clients rate something on a scale of 1–10) focused around 1 key issue, such as implementation – for example, "On a scale of 1–10, how clear do you feel on the next steps?"

When the time comes to discuss the assessment in the client meeting, the advisor could ask the client about their experience filling out the questionnaire and if there was anything else they wanted to share. The advisor could then further add to the conversation by asking follow-up questions about their client's experience.

Ultimately, this exercise can serve as an opportunity to catalzye a trust-building discussion about the dynamics of the relationship, where each party has a chance to be vulnerable. This conversation can indicate to the client that an advisor cares about and is willing to address the things that may not be going well for the client, and that they want to explore their own opportunities to enhance the relationship. Furthermore, clients may not even realize that these dynamics are something that can be talked about – sometimes, all that is needed to call out dysfunction is ‘just' to open space to talk about it, which can lead to not just a productive and collaborative meeting, but also improve the relationship overall.

When discussing these scores, advisors can pay particular attention to areas where everyone rates a high level of dysfunction (i.e., identifying statements as "rare" and rating them with a score of "1"). Additionally, advisors can more deeply explore areas where there is a considerable split in scores – e.g., if the advisor rates Question 8 (about a client's comfort level with disagreeing in a meeting) as a 3, and the client rates it as a 1, then that's a great area to focus in on.

Keep in mind that if everything is rated as a "3", perhaps the client actually is that content – in which case, that's a great thing to celebrate! It can sometimes be easy to gloss over the wins and entirely focus on opportunities for improvement, but 3s can open up areas to discuss the wins and progress over the course of the advisory relationship.

However, if a client rates a relationship as "3s all the way down", but their actions don't align with their ratings (i.e., a client reports that they are committed to all action items, but then doesn't act, then advisors may want to probe deeper. There may a chance that the client is further trying to avoid conflict or an awkward conversation.

Conversely, in the event that a client gets defensive or the conversation becomes unpleasant when diving deeper, advisors can reassure clients that this conversation is not an attack on either the advisor or the client – it's simply an exploration. Some tactics can include using "neutral" language, such as "Tell me more about…" or "what else do you notice with…", and thanking clients for their feedback, agreeing on certain points of feedback, and reflecting on how things can be improved. This, in turn, models a collaborative, supportive tone of the conversation and can help the client open up about where they see, feel, or contribute to dysfunction.

Resolving Areas Of Dysfunction

To paraphrase the author Leo Tolstoy (who was very talented but, unfortunately, did not write much on the subject of financial advisors, so we have to make do), happy client/advisor pairings share many similar traits, but each dysfunctional pairing is dysfunctional in its own way. Put another way: yes, there are similar behavioral pitfalls underlying each dysfunction. However, given how each advisor/client relationship is composed of different humans with their own quirks, preferences, and histories, it's likely that advisors will need to troubleshoot these relationships individually when they feel that some level of dysfunction has arisen.

Addressing dysfunction can require a considerable amount of emotional work; however, while they can in create a 'positive spiral' because solving real problems is rewarding, and gives clients and advisors a reason to celebrate – which in turn encourages discussing and working through real issues together.

In a functional relationship, friction still exists – but areas of friction are aired and resolved early on because everyone brings authentic talking points and ideas to every meeting. For clients and advisors, this can mean that clients bring the issues that matter most to them in calls, and confusion and reservations about recommendations are wholly discussed and resolved. Then, since everyone is fully bought into the recommendations presented, talking points are acted on more quickly, and clients (and their advisor) get to see the reward of solving real problems. This, in turn, incentivizes clients to continue to bring real, meaty discussion points to the table.

While a functional relationship takes work to build and maintain, advisors don't have to resolve dysfunctional relationships completely alone. Lencioni offers different solutions for the 5 areas in his dysfunction framework, which have been adapted here for advisors and their clients, which advisors can implement based on the results after holding the exercises and conversation above.

Rebuilding Vulnerability-Based Trust

Trust holds an interesting dichotomy in the advisor/client relationship – on the one hand, the relationship is inherently trust-based as prospects navigate the decision of entrusting an advisor with their money, financial decisions, and financial histories, despite, perhaps, a fear of judgment over some of their decisions, both past and present. On the other hand, advisors may feel the pressure to establish and demonstrate themselves as someone who is worthy of that immense trust. As an example, consider the preliminary prospecting process, where advisors and clients navigate how to quickly build and evaluate a high-trust relationship. And yet, the emotions and difficulties that come with talking about finances don't evaporate once a prospect becomes a client.

Nerd Note:

To give some perspective on how fraught talking about finances can be, a Capital Group study found that people rated money as the 'most taboo' topic; they would rather discuss topics such as marital problems, religious beliefs, and family disagreements with friends than personal finances.

For ongoing client/advisor relationships, there can be a natural cadence of shifting from very high-trust, open, problem-solving conversations to relative lulls in the financial issues being brought up in meetings – a cadence that often aligns with when issues arise in the client's financial life. The lulls may naturally fall away when the next financial situation arises, but if the ‘muscle' of openness and collaboration hasn't been ‘worked out' in a while, advisors can take a few steps to re-engage clients more fully.

To rebuild trust with an ongoing client, it may be helpful to hold a 'rediscovery' meeting (or incorporate a rediscovery session into an annual review call) to move clients from retained to engaged. Sometimes, just creating space for a client to say what's on their minds can be enough to rebuild personal rapport. In these re-engagement calls, Meghaan Lurtz recommends prompts such as the following:

- Tell me about significant changes since we last spoke.

- What changes are coming up soon?

- Give me your plans for the next 12–18 months, big or small. What are you planning for in the near term?

- On a scale of 1–10, how confident do you feel with your financial goals/financial plan?

- What do you worry about the most when it comes to your finances these days?

Additionally, using tools such as George Kinder's life planning questions may help advisors dig more deeply into how clients truly feel about their money, their money history, and their overall goals – and, as Lencioni notes, a crucial part of building trust is understanding what makes each other 'tick'. Notably, these re-engagement questions can also shed light on why clients may not be paying attention to the results. If there has been a significant change in their priorities, for one reason or another, then the goals that were set previously may no longer resonate with them.

Creating Conflict Profiles To Foster More Productive Disagreement

In his book, Patrick Lencioni refers to overcoming Dysfunction #2, the fear of conflict, as "mastering conflict", which is apt given that he encourages teams to foster productive conflict. In other words, conflict for the sake of conflict, which quickly becomes enmeshed in work politics, competitiveness, and pride, is not what Lencioni recommends. Instead, Lencioni posits that what is needed is "productive ideological conflict: passionate, unfiltered debate around issues of importance".

While some clients may have no problem with calling out areas where they disagree with or don't understand something, others may be paralyzed by the thought of pushing back. The latter behavior feels collaborative, but if a client privately disagrees or has questions, then they may be unlikely to act, regardless of what they agree on in a meeting.

As a starting point, advisors may want to ask clients who are reticent to raise issues about their "conflict profile". In a "conflict profile", a person summarizes how they respond to arguments or disagreements (as well as, potentially, strengths and weaknesses that come out of their approach). Most people are self-aware enough to share how they respond to conflict accurately (although how conflict-centric a client perceives themselves to be may be heavily reliant on their cultural background), which is notable as many of these profiles connect back to a person's personal history.

Asking clients to name and discuss their own conflict profiles can be immensely helpful to root out dysufunction, for a few reasons. First, as with other parts of potential dysfunction, the act of opening the conversation to how people deal with and respond to conflict often takes the 'teeth' out of their conflict response; once it's been openly discussed, a communication difficulty is easier to address and ultimately manage. Second, as Lencioni notes in his book, many parts of people's conflict profiles are rooted in their personal history, and reaching a better understanding of why a particular client is ‘that way' can be beneficial on its own. Third, every client is going to show up with a different history and way of interacting with conflict with disagreement, and it can be powerful to ask clients to list what they need in order to be set up for success in meetings.

As a light-hearted personal example [from Sydney] of what a conflict profile can look like: I was raised in a conflict-avoidant household where even inconveniencing others was seen as confrontational. On a recent trip to my hometown, I was reminded of this when my grandmother made the statement to no one in particular that "That lemonade sure looks delicious." – which was, of course, a request for 2 glasses of lemonade to be poured for her and my grandfather.

As one might imagine, making requests directly, let alone openly airing feelings and disagreements, is a skill I've had to develop in adulthood. So, I might describe my "conflict profile" as, "I was raised in a very conflict-avoidant household, so I really have to watch myself in conversations today to make sure I actually speak up when I disagree because otherwise, my instinct is to keep my head down."

Other examples of conflict profiles that clients may bring into the client/advisor relationship might include the following:

- I was raised as a part of a large, loud family, so unless you spoke up, you never got what you wanted. I have no problem advocating for myself (though I sometimes struggle to slow down enough to hear others out).

- During my time in graduate school, I really worked on the art of critical thinking and deep discussion. I might not think fast on my feet, but if I have 24 hours to think about something, I'll be sure to circle back with questions, thoughts, and talking points.

- Both of my parents were lawyers. I was expected to be able to 'prove my case', even as a kid. I don't mind disagreement – I actually really enjoy it!

While advisors may have a good guess about how their client deals (or doesn't deal) with disagreement in meetings, having clients articulate their own conflict profiles and brainstorm ways to overcome their tendencies in meetings can be both empowering and helpful (and advisors may also want to share their own tendencies as an additional way to build vulnerability-based trust and explore opportunities for better meetings). Discussing conflict profiles as an exercise during a meeting provides another opportunity to establish that everyone is on the same team, especially for clients who either struggle to voice disagreements or who come off as combative.

Nerd Note:

While not a perfect system, the Myers-Briggs Personality test offers a profile that measures personality type on 4 different scales: Extroversion/Introversion, iNtuition/Sensing, Thinking/Feeling, and Judging/Perceiving (e.g., if someone scores higher on the Introversion, Sensing, Feeling, and Judging traits, their profile would be ISFJ). The Myers-Briggs Company offers assessments on personality types, then models how the personality types show up in various scenarios, including relationships and disagreements. It can be a helpful starting point for clients who may be struggling to name their own tendencies.

Once these conflict tendencies have been aired, the client and advisor can set goals and identify boundaries around when, where, and how to set up space for questions and pushback. For example, if an advisor is working with a couple, they may assign a member of the couple to push back or ask at least 1 question about the proposed plan. And if someone is truly conflict-avoidant, being mindful to thank clients for bringing up questions or pushing back can go a long way to reinforce that this is how the advisor wants to know what the client thinks.

Finally, intentionally slowing down and creating space for disagreement and questions can be a powerful tool to solicit client feedback, which can help advisors target dysfunction and enhance the relationship. Even phrases, such as "I know I threw a lot at you. What questions do you have?" and "This was really hard for me to understand when I started in this profession; what else do you want to know about how this applies to you?" can encourage a natural conversation that allows the client to feel safe and reveal some vulnerability, while helping the advisor facilitate a comfortable space for questions, reservations, and disagreement.

Ultimately, while Dysfunctions 3–5 in the top half of the 5 dysfunctions "pyramid" (lack of commitment, avoidance of accountability, and inattention to results) are often the most visible, replacing the first 2 Dysfunctions in the bottom half of the pyramid (lack of trust, fear of conflict) with psychological safety and openness often eases many of the "top half" problems because issues, concerns, and questions are quickly and openly discussed.

Dysfunction can creep into even the best of teams, including client/advisor relationships – but with careful attention, mindfulness, and mutual work from the parties involved, many dysfunctional working relationships can be repaired. A functioning team is one where all parties feel that they have full permission to show up as themselves, hold disagreements, and work collaboratively towards mutually agreed-upon goals.

Leave a Reply