Executive Summary

Among all the different types of retirement account beneficiaries, those who are the surviving spouse of the original account owner receive the most preferential tax treatment when it comes to distributing the account's assets after the owner's death. While non-spouse beneficiaries face strict timelines – either starting Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) the year after the original owner's death and stretching them over their remaining life expectancy (if they were considered Eligible Designated Beneficiaries), or fully distributing the account within 10 years (if they were Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries) or 5 years (if they were Non-Designated Beneficiaries) – surviving spouses have more flexibility. They can delay their RMDs until the original account owner would have reached the required age for starting RMDs if they were still alive.

Furthermore, surviving spouses also have the option to roll over the inherited account into an account in their own name, allowing the account to be treated as if it had always been theirs. Meaning that the surviving spouse can wait until their own RMD age to start distributing from the account; and when RMDs do begin, they're able to use the more favorable Uniform Lifetime Table to calculate the RMD amounts (rather than the Single Life Table that's generally used to calculate the RMDs of account beneficiaries).

Prior to 2024, however, spousal beneficiaries faced complex tradeoffs when deciding whether to leave the account as an inherited account or to roll it over into their own name. For example, a surviving spouse under age 59 1/2 may want to do a spousal rollover to take advantage of the more favorable distribution schedule; but if they need to access any of the funds in the account before age 59 1/2, withdrawing them from the rollover account would incur a 10% early distribution penalty (which they wouldn't have incurred if they had left the account as inherited). And a surviving spouse who is older than the deceased spouse may want to leave the account as inherited in order to delay RMDs until the decedent's RMD age, but then they'd be subject to the less-favorable distribution schedule using the Single Life Table.

But the SECURE 2.0 Act created a new option for surviving spouses (effective starting in 2024) that changes the calculus for deciding which option to choose from. The new rule allows spousal beneficiaries who leave the account in the decedent's name to elect to use the Uniform Lifetime Table to calculate their RMDs rather than the Single Life Table as was required under the existing rules. Which means that spouses who choose to keep the account in the decedent's name for any reason will no longer be forced to take higher RMDs for doing so.

Notably, there may still be reasons to complete a spousal rollover in spite of the new Spousal Election rule. For instance, surviving spouses who are younger than the decedent can delay RMDs for longer after rolling the account over; additionally, rollover accounts generally have more flexible and favorable options for the surviving spouse's own beneficiaries (especially if the surviving spouse later remarries). Meaning that, in many cases, the best option might be to keep the account under the decedent's name until RMDs begin and then roll it over into the spouse's name thereafter.

The key point is that even though the new Spousal Election may seem to complicate the planning picture for surviving spouses by adding yet another option, it actually serves to benefit surviving spouses by reducing the tradeoffs between inherited account and spousal rollover options. And while different spousal beneficiaries may have a different 'optimal' choice depending on their own circumstances, the consequences of making the 'wrong' choice are now much less than they were under the old rules!

When the owner of a retirement account like a 401(k) plan or IRA passes away, it kicks off a complex series of events governed by distribution rules that change depending on who is named on the account's beneficiary form.

In general, the rules for inherited retirement accounts (which were primarily codified by the original SECURE Act passed in December of 2019, and subsequent IRS regulations that were finalized in July of 2024, for account owners who died in 2020 or later) sort beneficiaries into 3 different groups:

- Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., a spouse or minor child of the account owner, a disabled or chronically ill individual, or someone who is no more than 10 years younger than the account owner), who can "Stretch" distributions from the account over their remaining life expectancy;

- Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., any person who doesn't qualify as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary), who are required to fully distribute the account by the end of the 10th year following the account owner's death; and

- Non-Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., any non-person beneficiaries, such as charitable organizations and trusts that don't qualify as See-Through Trusts, as well as when no one at all is listed as a beneficiary and the account is passed via will or intestacy statutes), who are required to fully distribute the account by the end of the 5th year following the account owner's death.

But when the beneficiary of a retirement account is the account owner's spouse, although they're considered an Eligible Designated Beneficiaries in the list above, they're actually subject to a unique set of rules that apply only to surviving spouses – which, at least up until 2024, have been largely unchanged since well before the SECURE Act.

However, the SECURE 2.0 Act (passed in December of 2022), and new Proposed Regulations (issued in July of 2024), introduced a key change to the rules for spousal beneficiaries starting this year (2024) which, while not entirely upending the surviving spouse rules, will impact how spousal beneficiaries plan for distributions from their inherited retirement accounts going forward.

The Existing (Pre-SECURE 2.0) Spousal Beneficiary Rules

Prior to 2024, when a married owner of a retirement account like a 401(k) plan or an IRA passed away, their surviving spouse generally had 2 options for handling the account: 1) leave the account as an inherited retirement account in the decedent's name; or 2) roll over the inherited retirement account into a retirement account under their own name. Both of these options are still available under the new rules, so it's worth reviewing them as a refresher on the existing rules.

The "Inherited Account" Option

The first option – and what has been effectively the default option for spousal beneficiaries since it requires no action on the part of the surviving spouse – is to leave the account as an inherited retirement account in the decedent's name.

Normally, an Eligible Designated Beneficiary must begin taking RMDs from an inherited account in the year following the death of the original account owner. However, surviving spouses who leave the account under the decedent's name can take advantage of a special rule available only to spousal beneficiaries under Sec. 1.401(a)(9)-3(d) of the IRS's Final Regulations on RMDs: If the deceased account owner, at the time of their death, had not yet reached their Required Beginning Date (RBD) – which is generally April 1 following the year when they reach their "Applicable Age" (age 73 if born between 1951 and 1959, or age 75 if born in 1960 or later) – the surviving spouse can delay RMDs until the year the deceased spouse would have reached their Applicable Age. (If the deceased spouse had already reached their RBD, the surviving spouse's RMDs from the inherited account begin in the year after the decedent's death, as is the case with all other beneficiaries.)

Once RMDs begin, the surviving spouse calculates their RMD amount each year using their own life expectancy from the Single Life Table.

Example 1: Aimee (born in 1956) is an IRA owner who is married to Bart (born in 1951). Aimee passes away in 2024, the year that she turns 68.

Because she has not reached her Required Beginning Date yet (which would have been April 1 of 2030, the year following the year she would have reached her Applicable Age of 73), Bart is allowed to delay taking any RMDs from the account until 2029 when Aimee would have turned 73.

Imagine the value of the inherited IRA as of December 31, 2028, is $250,000. For the first RMD in 2029, Bart would divide the previous year-end account value by the life expectancy for his age (78) from the Single Life Table, which is 12.6. Therefore, the first RMD is $250,000 ÷ 12.6 = $19,841.

For years after the initial RMD, surviving spouses recalculate their RMD from the inherited account based on the Single Life Table number for their age each year – which is different from all other Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, who must use the Single Life Table number for their age in the original account owner's year of death, minus one for each subsequent year.

Example 2: In the case of the inherited IRA from Example 1 above, imagine the IRA's value as of December 31, 2029, is $240,000.

Bart's 2030 RMD would be calculated by dividing the previous year-end value by the life expectancy for his age in that year (79) from the Single Life Table, which is 11.9. Therefore, Bart's 2030 RMD is $240,000 ÷ 11.9 = $20,168.

Notably, the rule changes slightly when the original account owner dies after reaching their RMD age. Under Sec. 1.401(a)(9)-5(d) of the Final Regulations, rather than calculating the RMD solely based on the surviving spouse's life expectancy using the Single Life Table, it's instead calculated using the greater of 1) the surviving spouse's life expectancy using the Single Life Table (recalculated each year), or 2) the decedent's life expectancy, also using the Single Life Table (using the number for their age in the year of their death, minus 1 for each subsequent year).

Which means that surviving spouses who are older than the decedent generally start out by using the decedent's life expectancy rather than their own to calculate RMDs, before eventually switching to their own life expectancy once the 2 calculation methods 'cross over' and their own life expectancy becomes higher.

The "Spousal Rollover" Option

Another option available only to surviving spouses is the ability to roll over the inherited retirement account into a retirement account under their own name, which gives the account the same treatment as if the surviving spouse had opened and contributed to it themselves all along. Which means that a spousal beneficiary who rolls over an inherited account into their own name can wait until they reach their own Required Beginning Date before having to take RMDs from the account.

When RMDs begin after a spousal rollover, the RMD amounts are calculated based on the surviving spouse's own age using the Uniform Lifetime Table used for retirement account owners (rather than the Single Life Table used for beneficiaries) – which is generally more advantageous since it results in lower RMDs than the Single Life Table at any given age.

Example 3: Cherisse (born in 1952) is an IRA owner who is married to Daniel (born in 1957). Cherisse passes away in 2024 at age 72, and Daniel rolls the inherited IRA into his own name. Daniel is now treated as the owner of the account, which means he must take his first RMD for the year he turns 73 (2030) by April 1 of the following year (2031).

In this case, it doesn't matter whether Cherisse had reached her Required Beginning Date before death, or when she would have turned 73: Once Daniel rolls over the account, he's considered the account's sole owner, and his age is all that matters for RMD purposes.

For his first RMD from the rollover account in 2030, Daniel would divide the previous year-end account value by the life expectancy for his age (73) from the Uniform Lifetime Table, which is 26.5. If the value of the inherited IRA as of December 31, 2029, is $400,000, then Daniel's first RMD is $400,000 ÷ 26.5 = $15,094.

If the surviving spouse subsequently remarries someone who is more than 10 years younger than them (and who becomes the sole beneficiary of the rollover account), the rollover account's RMDs would be calculated using the Joint Life and Survivor Table rather than the Uniform Lifetime Table.

The Tradeoffs Between Spousal Beneficiary Options Under The Old Rules

At a high level, the choice between the inherited account and spousal rollover options comes down to 2 main factors: 1) The year in which RMDs begin for the surviving spouse; and 2) the life expectancy table that is used to calculate the RMD amounts. All else being equal, it's usually best to delay the RMD start date for as long as possible (to avoid having to withdraw from the account when the surviving spouse doesn't actually need the funds), and to minimize the amount of the RMDs when they do begin.

To that end, the rollover option – which lets the account owner use the Uniform Lifetime Table, compared to the inherited account option's requirement to use the Single Life Table – has historically almost always made more sense from a numerical standpoint than leaving the account in the decedent's name. Even though a surviving spouse who was older than the decedent might be able to delay RMDs for a few years more by keeping the account as inherited, the RMDs based on the Single Life Table would likely be much larger once they did begin – to the extent that they could push the surviving spouse into a higher tax bracket and wipe out any benefit from delaying the RMDs.

Example 4: Edouard (born in 1956) is an IRA owner who is married to Fannie (born in 1952). Edouard dies in 2024 at age 68, at which time his IRA is worth $300,000.

If Fannie leaves the IRA as inherited, she would be able to delay RMDs until 2029, when Edouard would have turned 73. To calculate her first RMD from the inherited account, Fannie would need to use the denominator for her age in 2029 (77) from the Single Life Table, which is 13.3. If the IRA's value has grown to $400,000 as of December 31, 2028, the year prior to Fannie's first RMD, Fannie's first RMD from the inherited account would be $400,000 ÷ 13.3 = $30,075.

If Fannie instead rolls over the account into her own name, she would be required to take RMDs based on her own age, which means she'd have to begin RMDs starting when she turns 73 in 2025. However, in this case, she'd calculate her first RMD using the denominator from the Uniform Lifetime Table for her age in 2025 (73), which is 26.5. If the IRA's value is $300,000 on December 31, 2024, Fannie's first RMD from the rollover account would be $300,000 ÷ 26.5 = $11,321.

In other words, the denominator used to calculate Fannie's first RMD is nearly twice as large using the rollover option (26.5) as it is when using the inherited account option (13.3), while the 4-year delay before beginning RMDs results in a higher IRA balance with the inherited option ($400,000) than the rollover option ($300,000), from which the RMDs are calculated. Which ultimately results in an initial RMD that's nearly 3 times higher using the inherited option ($30,075) than the rollover option ($11,321).

Despite the numerical advantages of the spousal rollover, there can still be certain cases when rolling the account over into the spouse's name would be less preferable, or even impossible.

For instance, if a surviving spouse rolls the account into their own name, the funds in the account can't be accessed without penalty until the surviving spouse reaches age 59 1/2, meaning that if the surviving spouse was younger than that and needed to rely on the inherited funds to meet their own living expenses, they would need to keep the inherited account in their deceased spouse's name (which allows them to make distributions at any time without penalty).

Although notably, there's no time limit on when a spousal beneficiary can roll over an inherited account into their own name, and so the surviving spouse can always simply keep the account as inherited until they reach age 59 1/2 before executing a spousal rollover, at which point their distributions from the rolled-over account would be penalty-free.

Nerd Note:

Sec. 1.402(c)-2(j)(4) of the IRS's Final Regulations on RMDs instituted a new rule that requires spouses to first satisfy a "Hypothetical RMD" requirement before making a spousal rollover – that is, they need to withdraw any RMDs they would have owed if the funds had been in their IRA all along before being allowed to roll over the remainder into their own name.

However, the Hypothetical RMD rule is only a factor if the surviving spouse has reached their RMD age, and the decedent would have also reached their RMD age, and the surviving spouse had opted to use the 10-Year Rule rather than Stretch distributions (allowing them to avoid any RMDs until the 10th year after the decedent's death).

In other words, it's unlikely to come up unless the surviving spouse was already using the 10-Year Rule to avoid RMDs. However, if the surviving spouse does decide to roll over the account in a year where they would have had an RMD from the account if it were still in the decedent's name, they will need to first take the inherited account RMD before completing the rollover.

One instance when the spousal rollover is almost never an option, however, is when the IRA beneficiary is a see-through trust with the surviving spouse as its beneficiary (which otherwise allows the trust to receive distributions based on the surviving spouse's RMD schedule). In that case, the surviving spouse is ineligible to roll the account over into their own name, meaning the inherited account (with its higher RMDs) is effectively their only option. (Although notably, the IRS has issued Private Letter Rulings allowing spousal rollovers from see-through trusts where the surviving spouse was the sole trustee and had unrestricted access to distribute the account's assets to themselves.)

And so the existing rules (up until 2024) created what was often a tradeoff for surviving spouses, where they could opt for either the more favorable RMD calculation schedule of the rollover option, or the more flexible pre-age 59 1/2 withdrawal options of the inherited account option, but not both. Moreover, surviving spouses who simply did nothing and left the account inherited as the 'default' option (perhaps not even knowing that they had the option to roll over the account) ended up stuck with higher RMDs than those who were proactive in rolling the account over. Which ultimately served to undermine the ostensibly favorable tax treatment afforded to surviving spouses over other types of beneficiaries.

The SECURE 2.0 Act's New Spousal Election To Calculate RMDs With The Uniform Lifetime Table

The SECURE 2.0 Act created a new option, in addition to the 2 existing options above, for spousal beneficiaries of IRAs and employer retirement accounts, which has helped alleviate some of the tradeoffs between the options that existed under the old rules.

The law gives surviving spouses who leave the inherited account in the decedent's name the ability to elect to be treated "as if the surviving spouse were the employee" (i.e., the decedent) for RMD purposes, with the key distinction being that spouses who make the election are allowed to use the Uniform Lifetime Table – rather than the Single Life Table – to calculate RMDs once they begin. The new election option became effective starting in 2024 (for surviving spouses whose first RMDs begin in 2024 or later), and recently issued IRS Proposed Regulations fleshed out the details of what had been a sparsely worded provision of SECURE 2.0.

Calculating RMDs Under The Spousal Election

As noted earlier, under the previous rules, spousal beneficiaries who leave the account under the decedent's name were limited to using the Single Life Table (based on their own age) to calculate the amount of their RMDs. But with the new Spousal Election, the surviving spouse can now use the Uniform Lifetime Table (again, based on their own age), rather than the Single Life Table, to calculate their RMDs once they begin. In other words, the Spousal Election allows surviving spouses to use the Uniform Lifetime Table – and accordingly be subject to lower RMDs – without needing to roll the account into their own name to do so.

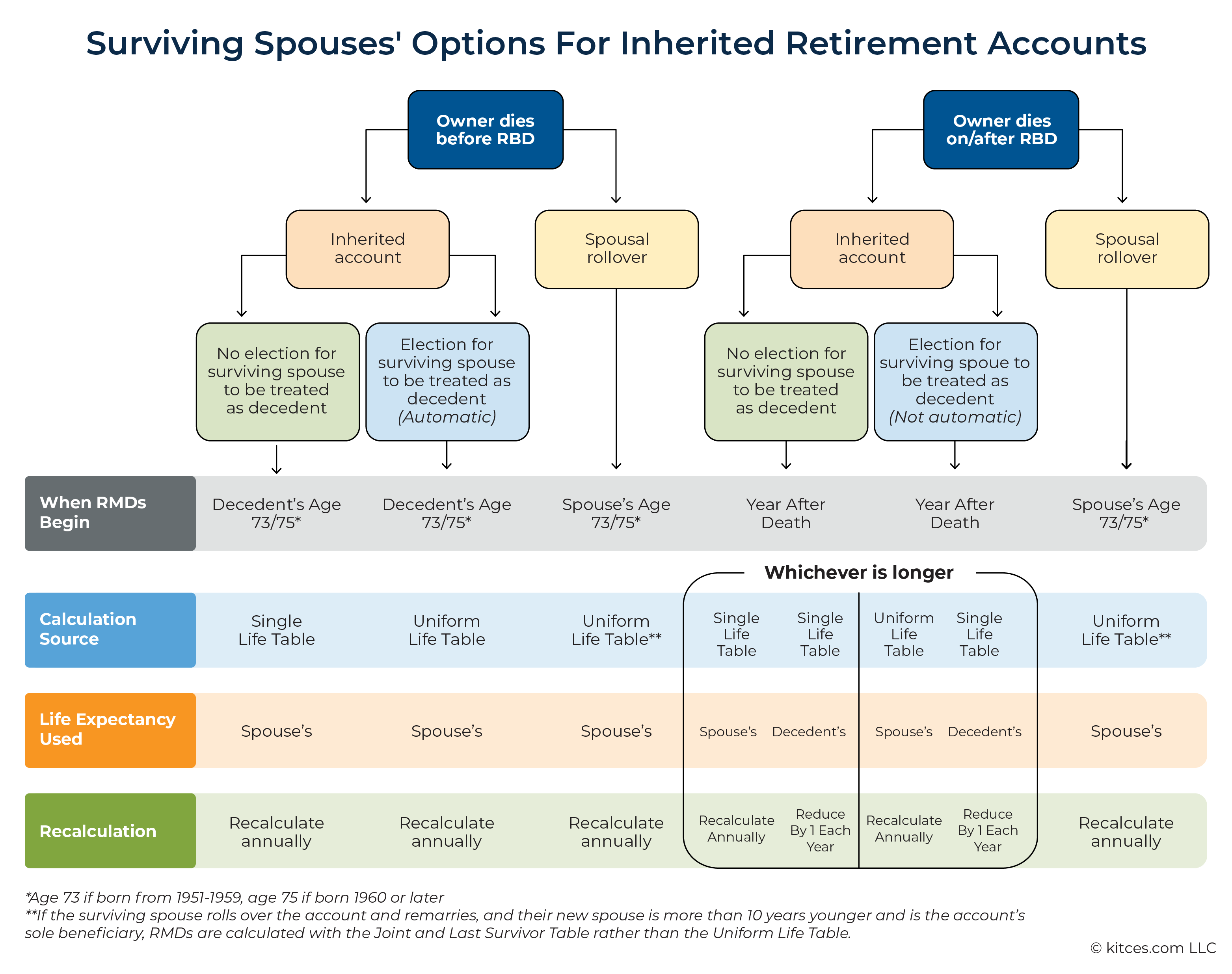

As was the case with the existing inherited account rules, the actual RMD calculation for the Spousal Election depends on whether the original account owner passed away before their Required Beginning Date (RBD), or on or after their RBD.

If the original owner dies before their RBD, the surviving spouse would be able to delay taking any RMDs from the account until the original owner would have reached their Applicable Age (which is still the case whether or not the Spousal Election is in effect). At that point, to calculate their RMD, the surviving spouse would use their life expectancy, based on their own age, from the Uniform Lifetime Table. In each subsequent year, the surviving spouse would recalculate the RMD amount using their current age.

If the original account owner dies on or after reaching their RBD, the RMD would instead be calculated using the greater of 1) the surviving spouse's life expectancy using the Uniform Lifetime Table (recalculated each year), or 2) the decedent's life expectancy, using the Single Life Table (using the number for their age in the year of their death, minus 1 for each subsequent year). This is similar to the existing rule for inherited accounts without the Spousal Election, except the surviving spouse would use the Uniform Lifetime Table in calculating their own life expectancy rather than the Single Life Table (although the decedent's life expectancy is, confusingly enough, still calculated using the Single Life Table). In practice, this means that if the surviving spouse is more than 10–12 years older than the decedent, the decedent's life expectancy will usually be used to calculate the surviving spouse's RMD.

The IRS's Proposed Regulations specify that the Spousal Election is automatically deemed to have been made if the original account owner died before reaching their RBD. Otherwise, the election is not deemed automatic – although retirement plans may decide to make it the default choice so surviving spouses aren't required to make it proactively. The Proposed Regulations also state that making the Spousal Election does not prevent a surviving spouse from rolling the account over into their own name later on – meaning that the Spousal Rollover will still be an option in future years.

Effectively, then, there are now 3 different options for surviving spouses:

- Make the spousal rollover;

- Leave the account as inherited and make the Spousal Election; or

- Leave the account as inherited and not make the Spousal Election.

Each option has its own set of rules around when RMDs begin, whether to use the Single Life or Uniform Lifetime Table to calculate the RMDs, and whether to use the spouse's or the decedent's life expectancy. Oh, and the rules can also change depending on whether the original account owner died before or after reaching their Required Beginning Date (RBD).

All of which, as shown below, adds up to a lot of factors for surviving spouses to consider when deciding which option to choose from.

Viewed altogether, however, the real effect of the new Spousal Election is to combine characteristics of the already-existing spousal rollover and inherited account options into a third quasi-hybrid option, allowing the surviving spouse to use the Uniform Lifetime Table to calculate their RMDs based on their own age (as the spousal rollover allows) while also letting them delay RMDs until the decedent's Required Beginning Date and take penalty-free withdrawals prior to age 59 1/2 (as the previous inherited account option allowed).

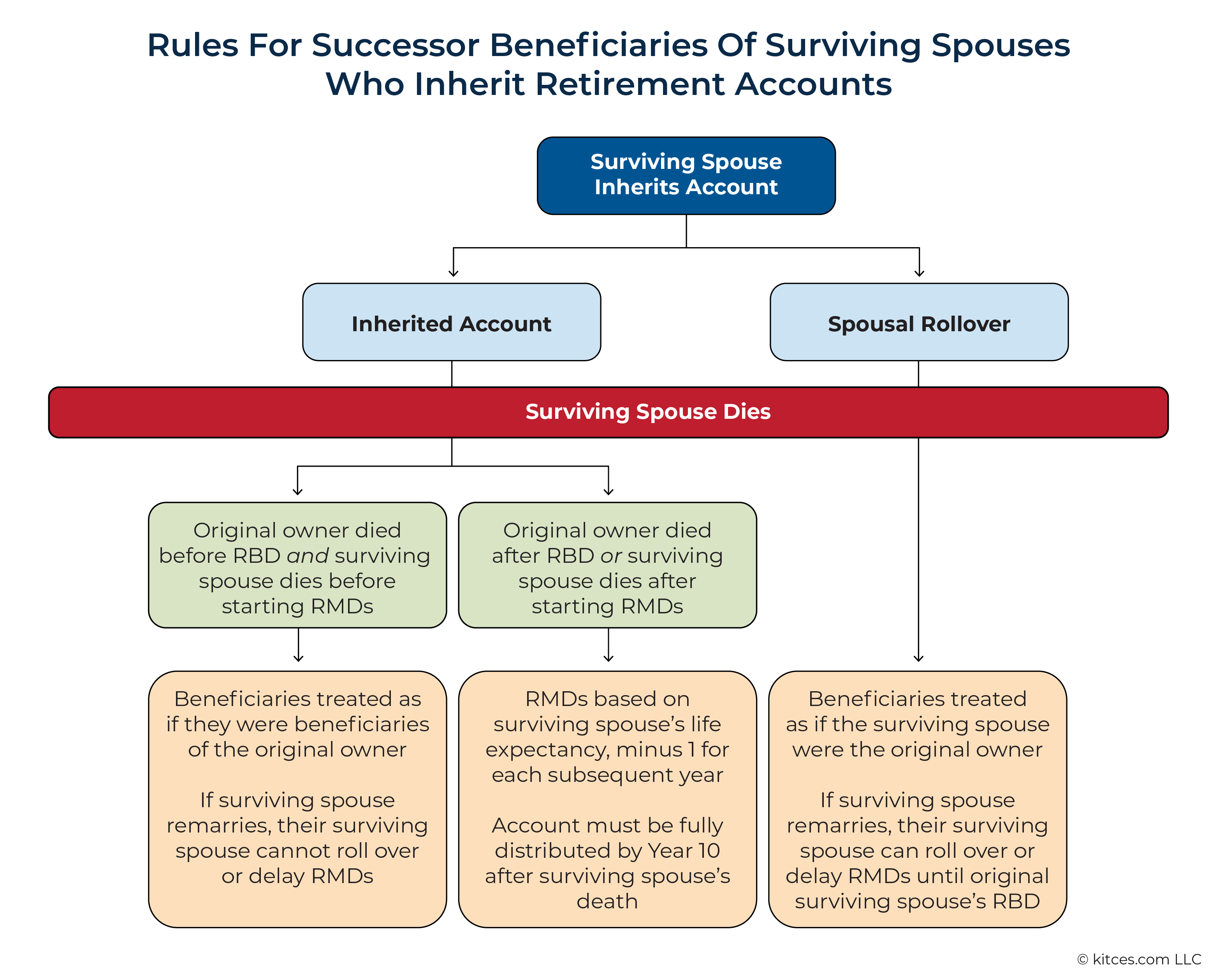

Distributions After The Surviving Spouse's Death

Beyond what happens during a surviving spouse's lifetime, there's a whole new set of distribution rules that kick off once the surviving spouse passes away, which again depend on whether the surviving spouse had chosen to leave the account as an inherited account under the original owner's name or instead roll it into an account under their own name.

Surviving Spouse's Beneficiaries With The Inherited Account Option

The existing 'successor' beneficiary rules for the beneficiaries of surviving spouses are (mercifully) the same for all inherited accounts regardless of whether or not the surviving spouse had made the Spousal Election to use the Uniform Lifetime Table in calculating their own RMDs. However, they can change depending on whether RMDs from the account had already begun – either because the original account owner had reached their Required Beginning Date (RBD), or because the surviving spouse had begun taking RMDs when the original owner would have reached their Applicable Age.

If the original account owner had not yet reached their Required Beginning Date (RBD) upon their death and the surviving spouse dies before commencing RMDs in the year the original owner would have reached their Applicable Age, then the surviving spouse's beneficiaries are treated as if they were beneficiaries of the original owner, not as "successor beneficiaries" of the surviving spouse. Which means that, while successor beneficiaries usually cannot be considered Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and must fully distribute the account by (at the latest) 10 years after the original beneficiary's death, a surviving spouse's beneficiary can qualify as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary – assuming they meet the Eligible Designated Beneficiary criteria to begin with – and can stretch distributions over their remaining life expectancy.

If the surviving spouse's beneficiary is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary or a Non-Designated Beneficiary, then they would be required to distribute the account fully by the end of either the 10th year (for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries) or the 5th year (for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries) after the surviving spouse's death. (Although if the surviving spouse remarries and then dies while the account remains an inherited account, the 'successor' spouse wouldn't be allowed to delay RMDs from the account beyond the year after the original surviving spouse's death, nor can they roll it over into their own name.)

If the original account owner dies after their RBD or if the surviving spouse has begun taking RMDs after the owner would have reached their RBD, there's no more distinction between Eligible, Non-Eligible, and Non-Designated Beneficiaries; instead, they're simply considered successor beneficiaries of the surviving spouse, and the whole account must be emptied by the end of the 10th year after the surviving spouse's death. Additionally, the successor beneficiary must take RMDs each year starting in the year after the surviving spouse's death, calculated based on the Single Life Table number for the surviving spouse's age in the year of their death, minus 1 for each subsequent year (up until Year 10, when the remaining account balance must be distributed).

Surviving Spouse's Beneficiaries With The Rollover Option

If the surviving spouse rolls over the account into their own name, all of the subsequent distribution rules apply as though the surviving spouse were the original account owner to begin with, and the surviving spouse's beneficiaries then use the 'normal' beneficiary rules under the SECURE Act. If the surviving spouse's beneficiary is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, then they can stretch distributions over their own life expectancy; if the beneficiary is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, then they are subject to the 10-year rule; and if the beneficiary is a Non-Designated Beneficiary, then they are subject to the 5-Year Rule. (And if the surviving spouse were to remarry and pass away after rolling over the account into their name, this would kick off a whole new spousal beneficiary sequence for their surviving spouse, following all the 'primary' spousal beneficiary rules as described earlier.)

From the perspective of the surviving spouse and their beneficiaries, then, it's clearly better for them to roll over the account at some point while they're still alive if their beneficiaries are Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (since those beneficiaries will get Stretch treatment of the remaining account balance regardless of whether the surviving spouse has begun taking RMDs from the account), and especially if the surviving spouse remarries at some point (because the new spouse would subsequently be able to take advantage of all the same surviving-spouse options that had been available to their deceased partner, the 'original' surviving spouse).

In all, when deciding which option to choose, spousal beneficiaries would be wise to consider not only which option might offer the greatest ability to minimize their own RMDs, but also which one might offer the most flexibility to minimize RMDs for their beneficiaries.

Spousal Election Vs No Spousal Election Vs Rollover: How To Choose?

As mentioned earlier, under the old rules, the spousal rollover was nearly always the best option for surviving spouses purely from the standpoint of minimizing RMDs since it was the only option that allowed the surviving spouse to use the Uniform Lifetime Table in calculating their RMD amounts.

The new Spousal Election changes that calculus, though, since it provides another option to use the Uniform Lifetime Table in calculating RMDs. And importantly, the election is treated as automatic in cases where the account owner dies before their Required Beginning Date (and can be made the default option by plan administrators when the owner dies on or after their RBD), meaning that surviving spouses no longer need to proactively execute a spousal rollover in order to benefit from the favorable Uniform Lifetime Table calculation.

This automatic election can be hugely beneficial from a policy standpoint when many surviving spouses may not fully understand their options of rolling the account over versus leaving it in the decedent's name, or the implications of calculating RMDs with the Uniform Lifetime Table versus the Single Lifetime Table. Thus, it's logical to set the default option as one that at the very least doesn't impose punitively high RMDs on the surviving spouse if they do nothing with the account after they inherit it.

But in terms of deciding on the optimal choice for a surviving spouse to make, the Spousal Election brings a new set of considerations to the forefront.

First of all, it seems as though there's almost no scenario where it would make sense to leave an account as inherited and not make the Spousal Election. With the way the law and the Proposed Regulations are written, the only difference the Spousal Election makes is providing the surviving spouse the ability to use the Uniform Lifetime Table when calculating their RMDs after the original owner's death.

By definition, then, the choice between whether to elect or not elect the Spousal Election is always going to favor the election, since it reduces RMDs while keeping all other aspects of the inherited account option the same. (To that end, it's fair to wonder why Congress structured this as an optional election for the surviving spouse to make, rather than as simply the rule for all spousal inherited accounts, but that's a question to ponder for another day.)

So the real question going forward is whether the spousal rollover will continue to be the 'best' option most of the time (as it was pre-SECURE 2.0), or whether the Spousal Election substantively changes the considerations for surviving spouses around which option to choose.

To find the answer, it makes sense to run through a few different potential client scenarios involving clients of various ages to see where each option would work best.

Spouses Of The Same Age

First, we find that when both spouses are the same age, there's no difference in the RMD requirements between the spousal rollover and the inherited account with the Spousal Election:

Example 5: Geoffrey and Harriet are married and are both 70 years old (born in 1954). Geoffrey owns a retirement account worth $500,000 with Harriet as the sole beneficiary. Geoffrey passes away this year (2024).

If Harriet rolls over the account into her own name, she'll begin taking RMDs when she reaches her RBD at age 73 in 2027, calculated using the Uniform Lifetime Table number for her own age (which is 26.5). Assuming the account grows at 6% per year, it will be worth $561,800 at the end of 2026, the year before Harriet takes her first RMD. This is the value that her 2027 RMD amount is based on, so her RMD amount is calculated as $561,800 ÷ 26.5 = $21,200.

If Harriet chooses to leave the account as an inherited account, she'll be automatically treated as making the Spousal Election since Geoffrey died before his RBD at age 73. She'll also be required to start taking RMDs in the year Geoffrey would have reached his RBD at age 73 in 2027, and when her RMDs begin, they'll be calculated using the Uniform Lifetime Table number for her age (also 73), which again is 26.5. Which results in the exact same 2027 RMD calculation as above: $561,800 ÷ 26.5 = $21,200.

Under the old rules without the Spousal Election, if Harriet had left the account as inherited instead of rolling it over into her own name, she'd also commence RMDs in the year that Geoffrey would have turned 73, but the RMDs would be calculated using the Single Lifetime Table number for her age (16.4) rather than the Uniform Lifetime Table number (26.5). Which means her 2027 RMD would have been $561,800 ÷ 16.4 = $34,256, and that it would have been preferable for Harriet to rollover the account under the old rules if she wanted to reduce the RMD amount.

In the example above, since the RMDs are equivalent between the rollover or inherited account option, the decision may come down to whether Harriet has any Eligible Designated Beneficiaries or whether there's a chance she would remarry at any point. In each case, the rollover option (with its ability for successor beneficiaries to retain the Stretch treatment) might be the better choice.

Also, if the spouses in the example above were younger than age 59 1/2 (instead of age 70), another consideration would be whether Harriet would need to rely on distributions prior to reaching age 59 1/2 to supplement her income. Such distributions would come with a 10% early withdrawal penalty if Client B rolled the account into her own name but would be unpenalized if taken from an inherited account, making the inherited account the better option in this case.

As mentioned earlier, however, there's no time limit on when surviving spouses can roll over an inherited account into their name, so Harriet could always keep the account as an inherited account at least until the early distribution penalty no longer applies, after which she could roll the account into her name at any point when it might make sense to do so.

Older Surviving Spouse

Next is a case where the surviving spouse is older than the decedent spouse, where it might make more sense (at least initially) to keep the account as inherited:

Example 6: Irving is 65 (born in 1959) and is married to Julius, who is 75 (born in 1949). Irving dies in 2024 and leaves behind a retirement account worth $500,000, with her husband Julius as the sole beneficiary.

If Julius rolls over the account into his own name, he would need to begin taking RMDs immediately in the year following Irving's death (2025), since he has already reached his RMD age of 72. Assuming the account value at the end of 2024 is $500,000, Julius's 2025 RMD would be $500,000 ÷ 23.7 (the Uniform Lifetime Table number for Julius's age of 76 in 2025) = $21,097.

If Julius leaves the account as inherited, the Spousal Election would again be automatic since Irving had not reached her RBD. Julius would be able to delay taking RMDs until Irving would have turned 73 in 2032. Assuming Julius doesn't take any distributions from the account in the meantime and it grows at 6% per year, the account value would be $751,815 at the end of 2031, which means Julius's initial RMD in 2032 would be $751,815 ÷ 17.7 (the Uniform Lifetime Table number for Julius's age of 83) = $42,475.

As the example above shows, the benefit of delaying RMDs is offset by the fact that they are bigger when they do begin, both because the surviving spouse has gotten older (reducing the denominator used to calculate the RMD) and because the account grows in size over time.

Which is why, even when delaying RMDs by leaving the account inherited, it might still make sense to distribute something from the account each year up until RMDs start, especially if the future RMDs will be large enough to push the surviving spouse into a higher tax bracket.

To that end, the point of delaying RMDs isn't about taking $0 from the account for as many years as possible, so much as it is about having the flexibility to distribute enough to use up as much of the lower tax brackets as possible (without having to go any farther than that) – in order to avoid those dollars being taken out as future RMDs and taxed at a higher rate later on.

It's also worth noting that, if Julius in the example above has any Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, he may want to consider rolling the account over into his own name in 2031 before RMDs from the inherited account would have begun: The RMDs from that point forward would be the same with either option (since both would be calculated using the Uniform Lifetime Table amount for his age), but after the rollover, any Eligible Designated Beneficiary of Julius would be able to stretch RMDs over their own life expectancy rather than needing to fully distribute the account by the 10th year after Julius's death as would be the case if the account remained inherited.

Surviving Spouse Is More Than 10 Years Older

One situation that might come up less often, but is still worth flagging, is when the surviving spouse is significantly older – usually 10 years or more – than the deceased spouse, which tilts the decision towards leaving the account as inherited even after RMDs begin:

Example 7: Kira is 73 (born in 1951) and is married to Lamarr, age 90 (born in 1934). Kira dies and leaves behind a retirement account worth $500,000, with Lamarr as the sole beneficiary.

If Lamarr rolls the account into his own name, he would need to begin taking RMDs immediately in the year following Kira's death (2025), since he has already reached his own RMD age. Assuming the account value at the end of 2024 is $500,000, Lamarr's 2025 RMD would be $500,000 ÷ 11.5 (the Uniform Lifetime Table number for Lamarr's age of 91 in 2025) = $43,478.

If, however, Lamarr leaves the account as inherited and elects to be treated as the decedent, the calculation is slightly different because Kira had already reached her RMD age of 73 before her death. In this situation, the denominator for the 2025 RMD is the greater of the Uniform Lifetime Table number for Lamarr's age of 91 that year (11.5), or the Single Lifetime Table number for Kira's age of 73 in the year of her death, minus 1 for each subsequent year (16.4 – 1 = 15.4). Since 15.4 is the higher number, Lamarr's 2025 RMD from the inherited account is $500,000 ÷ 15.4 = $32,468.

So, while Lamarr's RMDs would start in 2025 regardless of whether he chose the spousal rollover or inherited account option, the inherited account RMD would be $11,010 less than the rollover account RMD in the first year.

Younger Surviving Spouse

When the situation is reversed and the surviving spouse is younger than the decedent, the spousal rollover would clearly be the better option when it allows the surviving spouse to delay RMDs until their own Required Beginning Date:

Example 8: Margo is 75 (born in 1949) and is married to Nathan, who is 65 (born in 1959). Margo dies in 2024 and leaves behind a retirement account worth $500,000, with Nathan as the sole beneficiary.

Since Margo had already reached her RMD age of 72, Nathan would need to immediately begin taking RMDs from the account starting in the year after Margo's death (2025) if he leaves the account as inherited.

If he instead immediately rolled over the account into his own name, however, he would be able to delay any RMDs from the account until he reached his own RMD age of 73 in 2032.

If Nathan in the example above had already reached his own RMD age – and wouldn't have been able to delay RMDs by making the rollover – it wouldn't make a difference whether he rolled over the account or not from the perspective of RMDs during his lifetime. But as illustrated in Example 5 where the spouses are the same age, it may be better to make a rollover to preserve more flexibility for Nathan's beneficiaries, particularly if any of them would be eligible to make Stretch distributions over their life expectancy if the account were rolled over.

Although the spousal rollover might be the better option in the final example above, what the previous examples show is that rolling over the account into the spouse's name should no longer be considered the best move by default. Each situation is going to need an analysis of the different options as in the examples above, while also considering other relevant factors like the surviving spouse's desire to take distributions from the account, the status of any beneficiaries of the surviving spouse, the likelihood of the surviving spouse remarrying, and whether the IRA beneficiary is a conduit trust which would eliminate the rollover option altogether.

That being said, there are a few general guidelines that might be helpful in deciding which strategy might be advantageous:

- If the surviving spouse is younger than the decedent spouse and has not yet reached their RBD, it will almost always be better to roll the account over (although if the surviving spouse is under age 59 1/2 and needs to take distributions from the account, it could make sense to delay the rollover until after the surviving spouse can take distributions penalty-free).

- If the surviving spouse is older than the decedent spouse, and the decedent dies before their RBD, it may make more sense to leave the account as inherited in order to delay RMDs until the decedent's RBD – although the surviving spouse may want to roll the account over at some point before (if even immediately before) the RMDs actually begin, in order to preserve more flexibility for their own beneficiaries.

- If the surviving spouse is the same age or older than the decedent spouse, and the decedent dies after their RBD (or if the surviving spouse is younger than the decedent spouse, and has already reached their own RBD), the RMDs will be the same whether the account is rolled over or left as inherited, meaning it comes down to other factors such as the beneficiaries of the surviving spouse – unless the surviving spouse is more than 10–12 years older than the decedent, in which case the RMDs will be lower at least initially when the account is left as inherited.

And when choosing any option that involves delaying RMDs, it's worth considering making at least some distributions from the account each year – whether it's a rollover account or an inherited account – if the surviving spouse is in a lower tax bracket than they'll be in once RMDs begin. This is especially true with younger surviving spouses where there could be potentially decades of tax-deferred growth before RMDs begin, which could lead to paying a much higher tax rate on the RMDs compared to drawing the account down gradually over time.

In that case, if the surviving spouse needed the funds from the account prior to age 59 1/2, they could leave the account as inherited and withdraw from it over time penalty-free. But if they don't anticipate needing the funds, they could instead roll the account over and make gradual Roth conversions to turn the tax-deferred growth into tax-free growth. The more years there are before RMDs begin, the more time there is to spread out the tax impact of distributing the account.

Although surviving spouses of retirement account owners get special treatment regarding their options for the inherited account that is often advantageous compared to non-spousal beneficiaries, the flip side is that, rather than being bound to a single mandatory distribution schedule, they're faced with a maze of options with the potential for very divergent outcomes. And added to that pressure is the possibility that it may not even be apparent whether choosing one option or the other was a good idea or a bad one until years or even decades down the line.

Ultimately, while the Spousal Election will undoubtedly make things better for surviving spouses who do nothing and leave the account as inherited compared to the old rules that would have forced them to take RMDs based on the Single Life Table, that still might not be the best move for many surviving spouses, who might be better off (at least eventually) rolling over the account into their own name. Like so many aspects of financial planning, spousal beneficiary decisions are a marriage of numbers (e.g., which option would delay and/or minimize RMDs the most) and more holistic concerns (like the surviving spouse's need for income and their desires for their own beneficiaries) to find the best course for preserving the retirement account assets for the surviving spouse and their survivors down the line.