Executive Summary

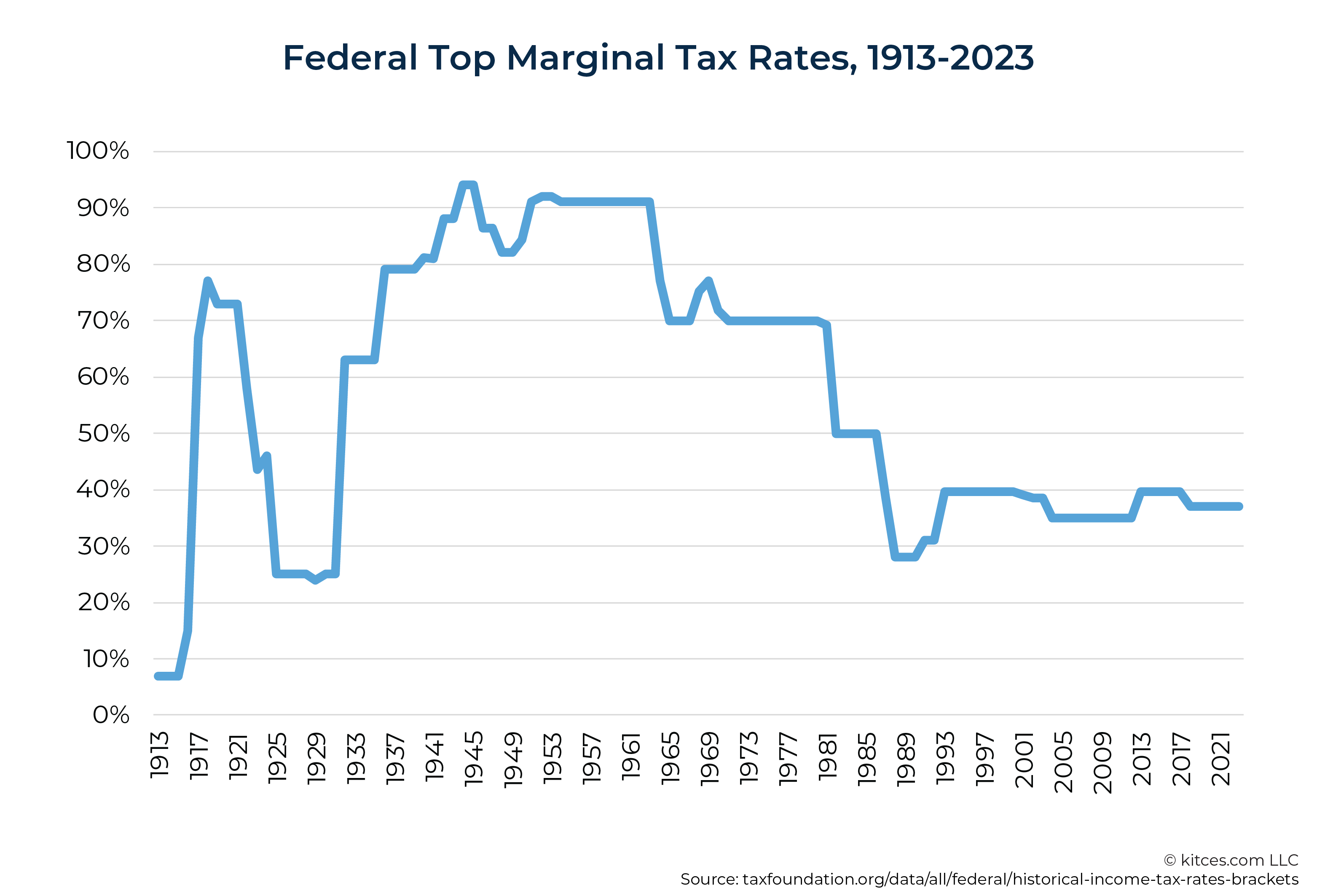

Over the last 60 years, the top Federal marginal tax bracket has steadily decreased from over 90% in the 1950s and 60s to 'just' 37% today. However, with the national debt expanding rapidly, observers of U.S. tax policy are predicting that Congress will inevitably be forced to again increase tax rates in order to raise revenue and balance the national budget – and that the current regime of relatively low tax rates will prove to be a temporary phenomenon.

From a financial planning perspective, the seeming implication of a likely rise in future tax rates would be that, given a choice between being taxed on income today or deferring that tax to the future, it makes more sense to be taxed today when taxes are lower than they'll be in the future. For example, if taxes were expected to rise in the future, it would be better to contribute to a Roth retirement account (which is taxed on the contribution, but not upon withdrawal) than to a traditional pre-tax account (which is tax-deductible today but is taxable on withdrawal). As a result, there's a common line of thinking that people saving for retirement should avoid pre-tax retirement accounts entirely and contribute (or convert existing pre-tax assets) to Roth instead – regardless of which tax bracket they're in today.

While it's true that the top marginal tax rate has decreased dramatically since the mid-20th century, the difference in the actual tax paid by most Americans has been far more modest. Because not only were very few households actually subject to the 1950s-era top tax rates (which were triggered at the equivalent of over $2 million of income in today's dollars), but the long decline in nominal tax rates has also come with the elimination of many loopholes and deductions that have resulted in more income being subject to tax. Which means that it seems less likely that Congress will simply raise the marginal tax brackets in the future than that they will further reduce the benefits of current tax planning strategies – possibly including those of Roth accounts themselves!

Furthermore, focusing only on tax rates at a national level ignores the fact that an individual's own tax rate is likely to change much more during their lifetime based on their own income and life circumstances. In particular, those nearing retirement may see a large swing from the upper tax brackets as they reach their peak earning years, to the lowest brackets upon retirement, and eventually stabilizing somewhere in the middle once they start receiving income from Social Security and Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). Which creates a tax planning opportunity to make pre-tax contributions while in the peak earning years, and then to convert funds to Roth after retirement – and as long as those funds can be converted at a lower tax rate than they were contributed, it still makes sense to contribute them to a pre-tax account.

Ultimately, while the idea that we currently live in an anomalously low-tax environment that will inevitably reverse course has its appeal, basing one's tax planning decisions around that assumption is still risky. Because even if taxes do creep up nationally, individuals who are already in the highest tax brackets today are still likely to be in a lower bracket upon retirement – which makes it better to contribute to a pre-tax account today and then withdraw (or convert) the funds at a lower rate later on!

The Roth-Vs-Traditional Decision

When a person is in their working years, they essentially have 3 'flavors' of account types that they can contribute to for their retirement savings. First, there are standard taxable accounts, where any investment income like dividends or interest is taxed in the year it's received, and capital gains are taxed in the year they're realized. Then there are the 2 types of tax-preferenced accounts that the Internal Revenue Code has carved out to incentivize people to contribute more towards their retirement savings: traditional pre-tax accounts (where contributions, plus any investment growth and income, are tax-deferred until the year they're withdrawn) and Roth accounts (where contributions are taxable in the year they're made, and any subsequent growth and income is tax-free).

Each type of account gets taxed at one point or another – either upfront in the case of a Roth account, upfront plus in every subsequent year for a taxable account, or upon withdrawal for a pre-tax account. However, the ability to either defer tax on investment growth and retain the full compounding value of the account (for a pre-tax account) or eliminate tax entirely on growth after paying tax on the original contribution (for a Roth account) means that people generally prefer the tax-preferenced retirement accounts over taxable accounts for their retirement savings. However, the decision of which type of account to contribute to – pre-tax or Roth – has long been a source of debate.

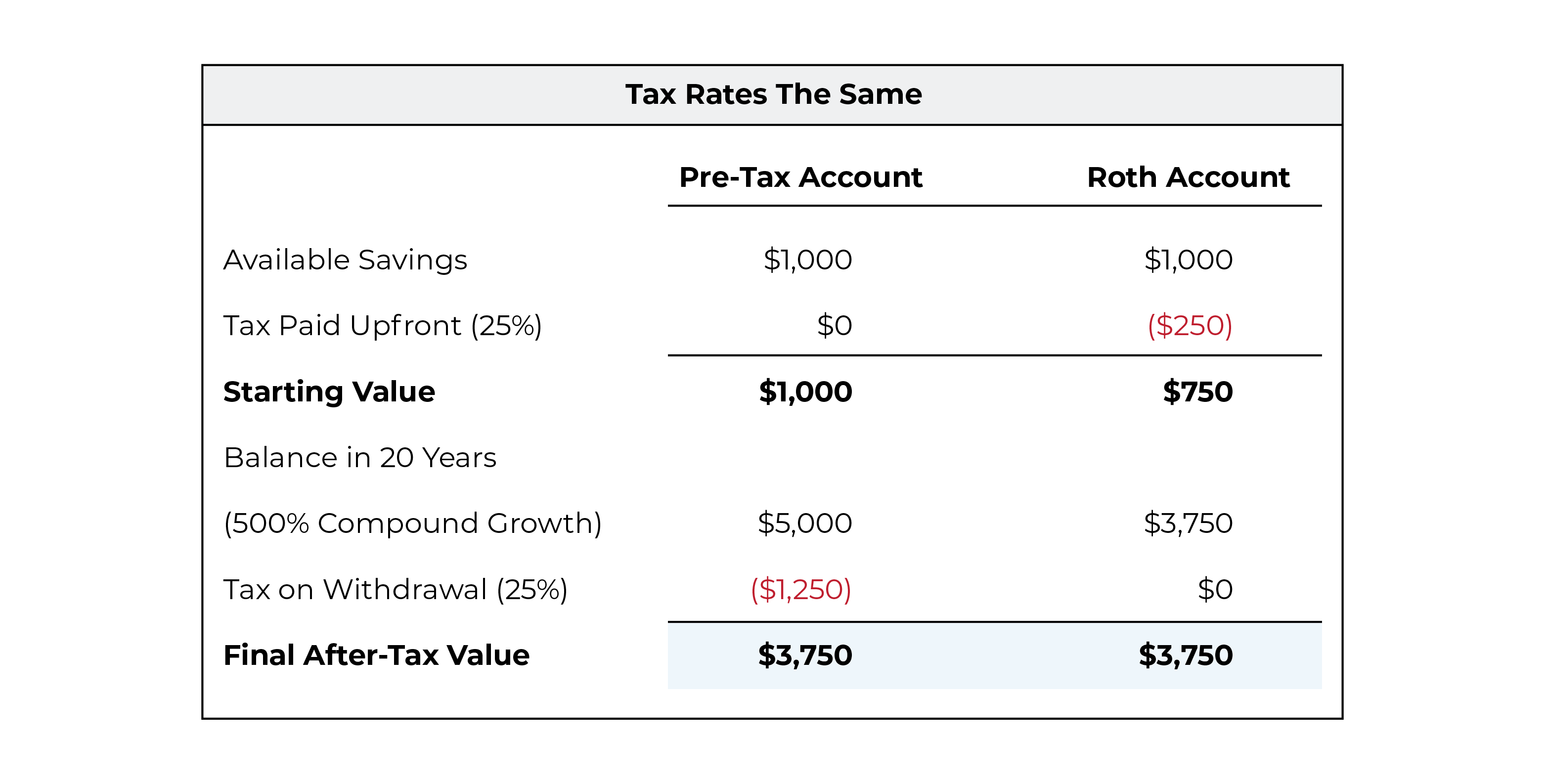

At a high level, the decision between a traditional and a Roth account comes down to the saver's tax rates now versus their tax rates when they expect to withdraw from the account. If the 2 rates are the same, then, in theory, it doesn't make any difference which account to contribute to.

For example, imagine someone who pays a 25% marginal tax rate both today and in retirement, with $1,000 in total to contribute to their retirement savings. If they contribute to a traditional account and their $1,000 contribution grows by 500% to $5,000 over the next 20 years, then they'll pay $5,000 × 25% = $1,250 in tax upon withdrawal, leaving them with $5,000 – $1,250 = $3,750 in after-tax value.

If they instead contribute to a Roth account, they'll pay $1,000 × 25% = $250 in tax upfront, leaving them with $750 to contribute to the account. If that grows by the same 500% over 20 years, then they'll have $3,750, all of which would be tax-free. In other words, as shown below, if the tax rate is exactly the same in the year of the contribution as it is in the year of withdrawal, both accounts will have the same after-tax value of $3,750 when they're withdrawn during retirement.

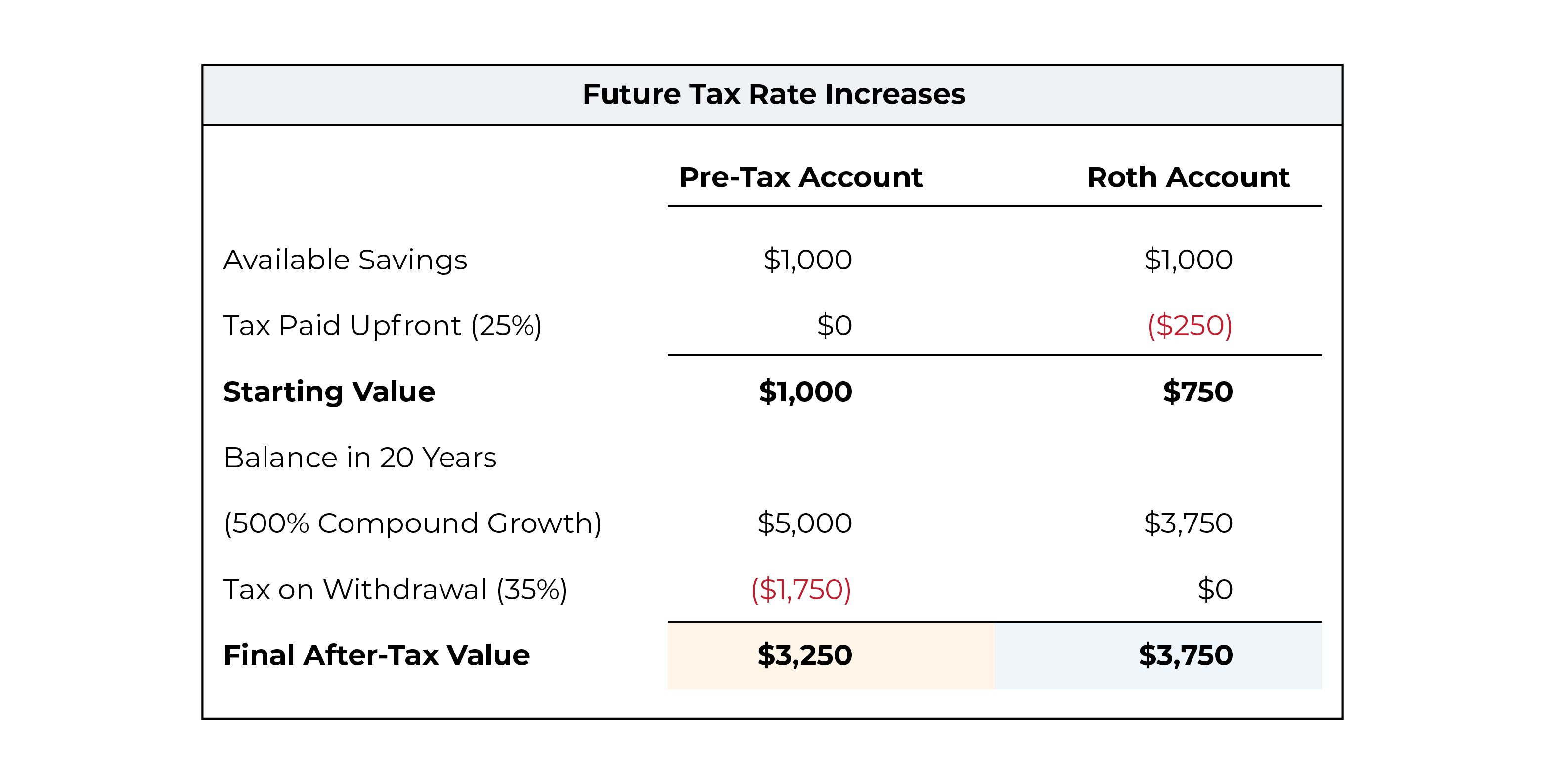

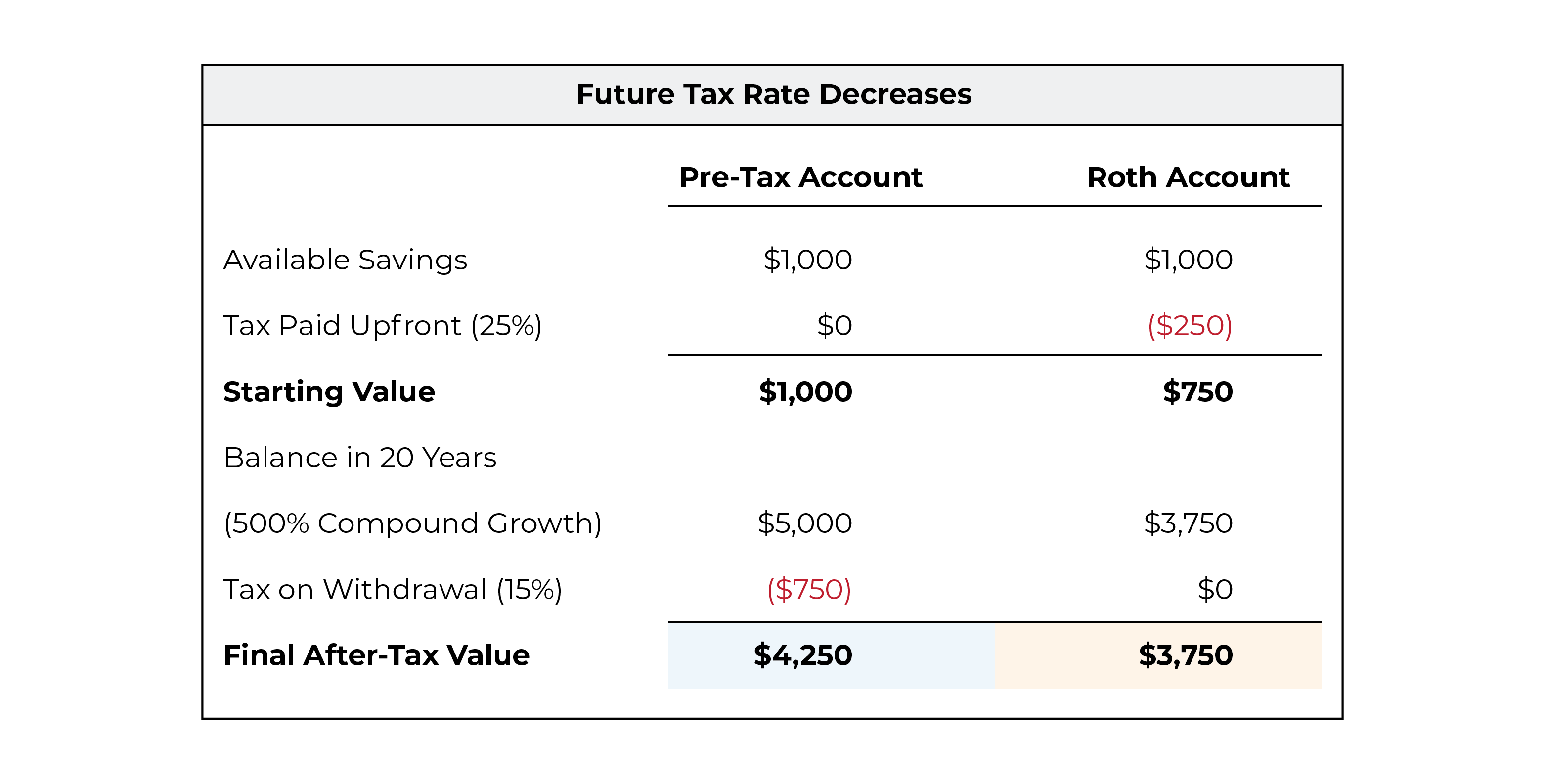

The pre-tax versus Roth decision does make a difference, however, when the saver's tax rate changes between the time of the contribution and the eventual withdrawal from the account.

If the tax rate goes up between contribution and withdrawal, the decision favors a Roth account. Using the same example as above, if the saver's tax rate increases from 25% today to 35% in the future, the pre-tax account's after-tax value decreases from $3,750 to $3,250 (since withdrawals from the account will be fully taxed at the higher future rate), as shown below. Meanwhile, the Roth contribution has already been taxed at the (lower) current tax rate and will not be exposed to any future tax increases.

However, if tax rates go down in the future, the situation is reversed and it would be better to contribute to a pre-tax account. Again using the example above, a decrease in the saver's tax rate from 25% today to 15% in the future results in the pre-tax account's value increasing to $4,250; while the Roth account, having already been taxed at the (higher) current rate, doesn't see any benefit from the future decrease in tax rates.

The Traditional Account "Time Bomb" Debate

For years, industry commentators have argued that the growing U.S. government deficit will inevitably lead Congress to raise income tax rates as a necessary measure to pay down the national debt. This, in turn, would cause those with savings in traditional, pre-tax retirement accounts to pay higher taxes when they withdraw their funds. Some commentators describe traditional accounts as tax 'time bombs', where the upfront deduction received for contributing to the account will eventually be swamped by the taxes paid on withdrawal as a result of Congress's need for revenue.

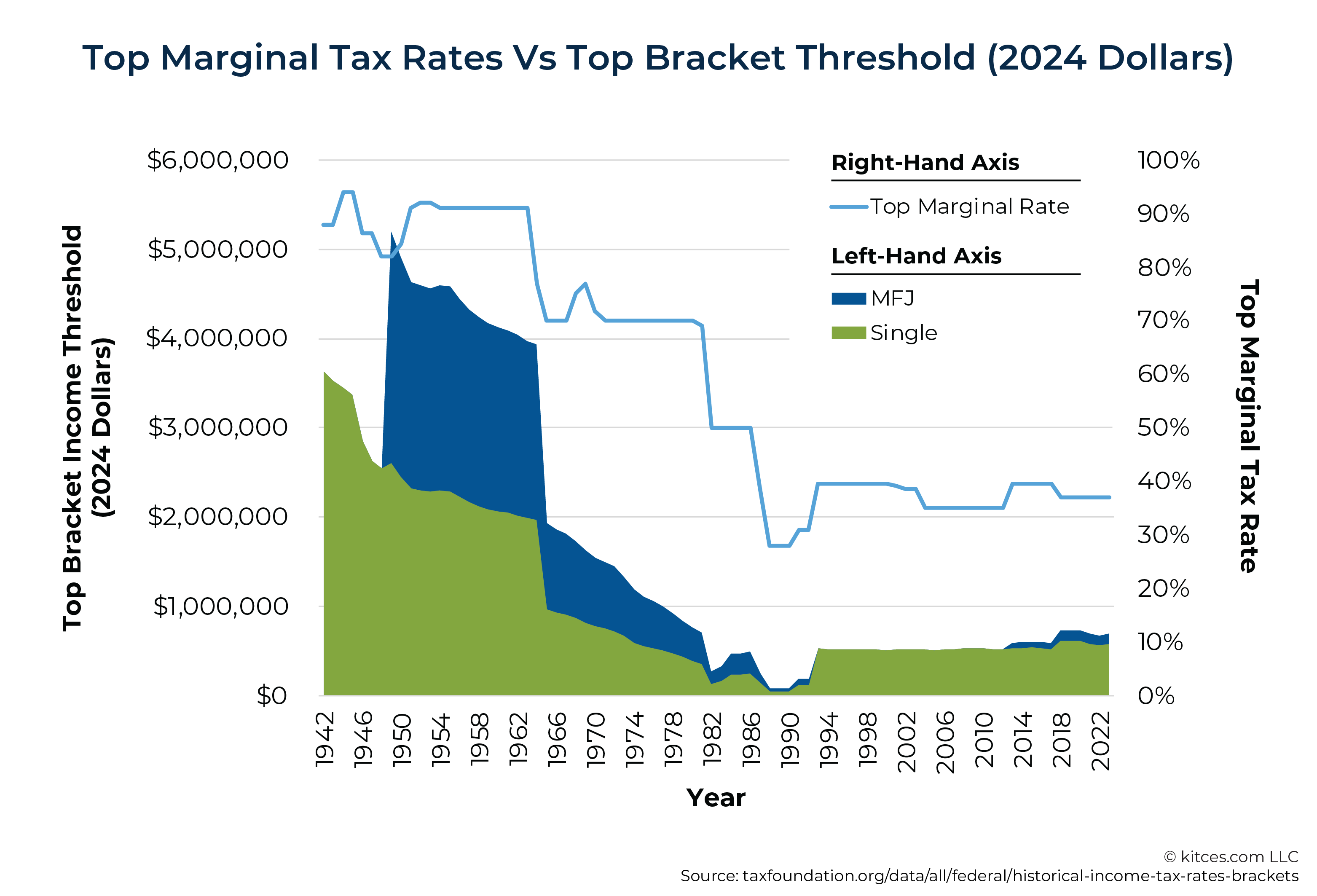

To illustrate their argument, commentators often use charts such as the one below showing the top Federal marginal tax rate over the years, pointing to mid-20th century tax rates of over 90% as proof of "how bad it can get" when Congress decides that people should pay more.

The story that the chart above tells is simple: Compared with most of the last century, we are paying historically low income tax rates today. And at the rate that the government is spending, Congress will need to again boost tax rates up to more historically 'normal' levels, potentially maxing out at the 70%–90% levels that prevailed from World War II up until the tax cuts of the Reagan era. Which would make it seem obvious that contributing to a traditional pre-tax account today is a bad idea since those funds could be taxed at significantly higher rates in the future than they would be today.

At the extreme, the history of the top marginal tax rate suggests that even taxpayers who are in the current 37% top marginal tax bracket ought to make Roth instead of pre-tax contributions – or even convert their existing pre-tax assets to Roth and pay tax on the conversion today in order for the funds to grow tax-free in the future – because of the high probability that the top marginal rate will increase in the future. As the thinking goes, those who pay taxes today to put funds into Roth accounts will protect themselves from any actions that Congress takes to raise revenue in the future.

However, there are 3 big flaws with the argument that people should avoid pre-tax retirement accounts and focus only on Roth contributions or conversions based on how today's top marginal tax bracket compares with the top rate throughout history.

Top Marginal Tax Rates Used To Be High, But Few People Actually Paid Them

The first flaw in the argument for avoiding pre-tax accounts is the assumption that everyone who is in the top marginal tax bracket today would have also been subject to the (much higher) top tax rates that existed throughout much of the 20th century. However, the structure of the tax system at the time meant that, when the 90%+ tax rates were in effect, very few people actually paid them.

As shown in the graph below, the taxable income threshold for reaching the top income tax bracket, as measured on the left-hand axis (adjusted to 2024 dollars) decreased in tandem with the top marginal rate itself, as shown on the right-hand axis, throughout the second half of the 20th century. In the 1950s and early 1960s, when the top rate was at its highest sustained level of 91%, single filers would have needed the equivalent of at least $2 million in taxable income, and married filers would have needed at least $4 million, to actually be taxed at the highest rate. And that threshold was still over $1 million up until well into the 1970s.

Even if the U.S. were to go back to 1950s-style rates, then, only those with the very highest incomes would actually reach the threshold. For context, according to IRS data, only about 0.5% of taxpayers who filed a tax return in 2021 had over $1 million in adjusted gross income. In other words, historical top marginal tax rates simply aren't very relevant for the vast majority of people deciding on the type of retirement account to use. Because even most of the people who fall into the highest tax bracket today would be nowhere close to the highest bracket under the 'old' system!

Modern Tax Reform Focuses More On Expanding The Tax Base Than Raising Rates

The second flaw in looking at the past as a guide for what future tax rates will hold in store is the assumption that, when Congress decides it needs to raise more revenue, it will do so simply by raising marginal tax rates to their historical levels. In practice, however, raising tax rates has proven extremely politically unpopular over the last 40 years, and so the way that Congress has generally approached reforming the tax code since the Reagan era has been to keep the tax brackets relatively compressed while changing how income was taxed and which deductions and credits were available for taxpayers.

For example, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 lowered the top marginal tax rate from 50% to 28%, but it also eliminated some significant deductions available to individual taxpayers, including personal interest on not just mortgages but also credit cards, auto loans, and any other types of loans that incurred interest. Additionally, it disallowed losses from real estate and passive investments, while also expanding the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). All of which served to eliminate many of the tax shelters that had allowed people to avoid paying the higher marginal tax rates (and sometimes, to avoid paying any taxes at all) in the years prior.

Another more recent example of how Congress has sought to increase tax revenue without actually raising tax rates is the original SECURE Act from 2019, which eliminated the ability of many retirement account beneficiaries to take "stretch" distributions over their own life expectancy and imposed the 10-Year Rule requiring them to fully distribute the account within 10 years of the original owner's death. With a more compressed distribution schedule, emptying the retirement account – particularly if it's a large one – makes it more likely that distributing the funds will push the beneficiary into a higher tax bracket. This effectively increases the tax paid on the funds in the account, even though the tax brackets themselves haven't changed.

All of this is to say that, even if it seems likely that Congress will need to raise revenue to address the deficit, it doesn't necessarily make sense to plan as though tax rates will change significantly (except, perhaps, for those in the very top bracket, which has seen more variability than other brackets over the last 40 years). Rather, it's more likely that changes will be made to the taxable income base, either by changing the way taxable income is calculated for everyone or by further altering the rules for how retirement accounts are taxed. At the extreme, even Roth accounts could see their benefits curtailed by a future Congress if they become seen as too generous of a tax shelter, e.g., by subjecting them to RMDs like pre-tax accounts already are, or by limiting contributions or tax-free withdrawal treatment above a certain account value. There's no way to know what shape future tax policy will take, but given the last 40 years of tax law changes, one of the least likely scenarios would be for Congress to simply raise marginal rates while leaving the rest of the existing structure of tax law intact.

Tax Rates Change More Based On Individual Life Events Than On Tax Policy

The third flaw in the argument to avoid pre-tax accounts is in looking at the decision only through the lens of how tax rates change nationally over time while ignoring how tax rates change on an individual level. Put simply, most people's income (and therefore their marginal tax bracket) fluctuates throughout their taxpaying lives, and those changes tend to be far more frequent – and often more significant – than any changes in tax rates at a marginal level.

Career paths ebb and flow: A person could earn well in a job for a few years, then decide to quit and start their own business where they earn very little as the business gains traction, and then end up earning much more than they had in their original job. Family situations also contribute to fluctuating income, as one spouse may take time out of their working career to raise kids or care for an aging parent. And most people aim to retire, or at least wind down their working careers, at which point their income will likely decline steeply (although commencing Social Security benefits and beginning RMDs from retirement accounts may cause it to increase again later in retirement).

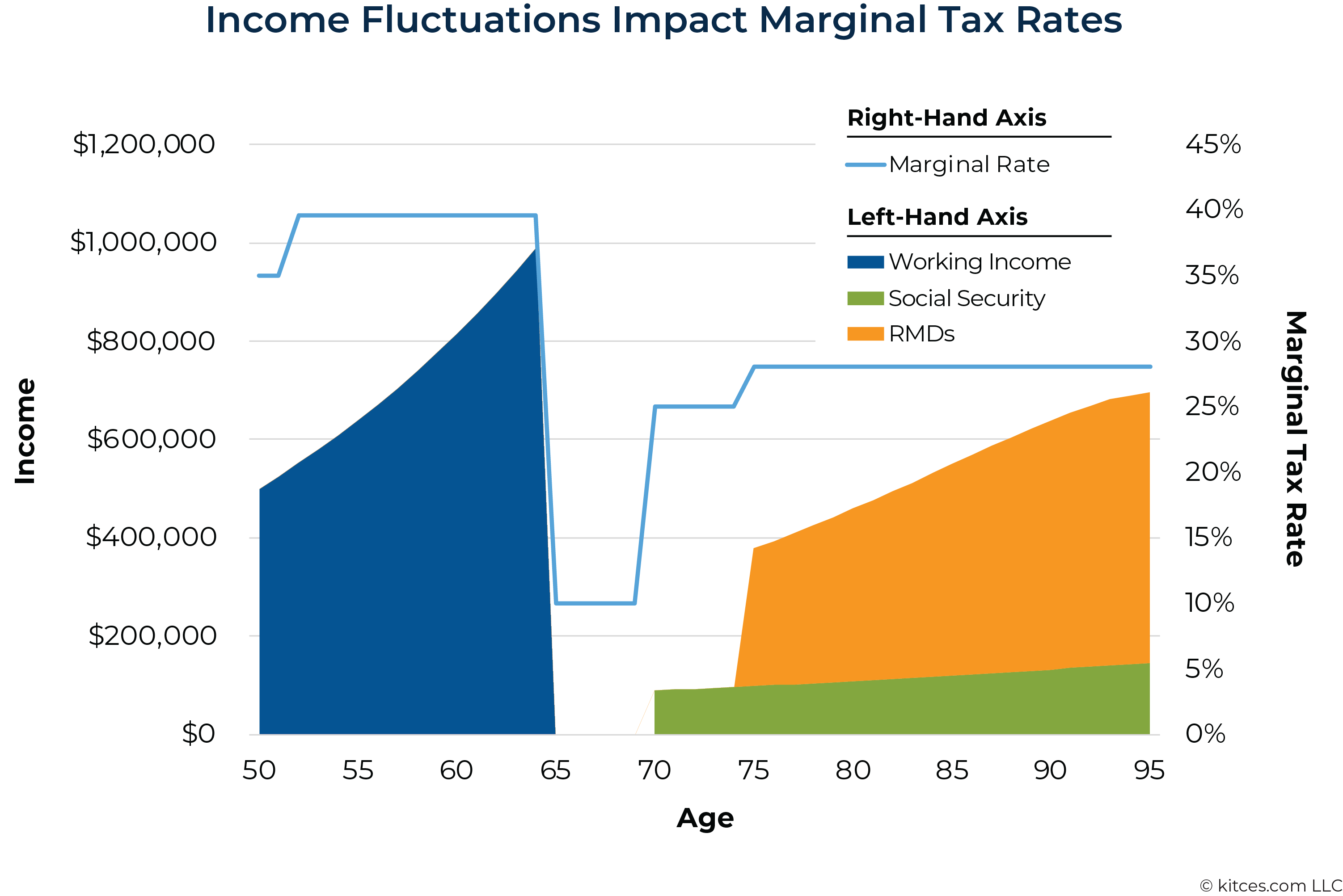

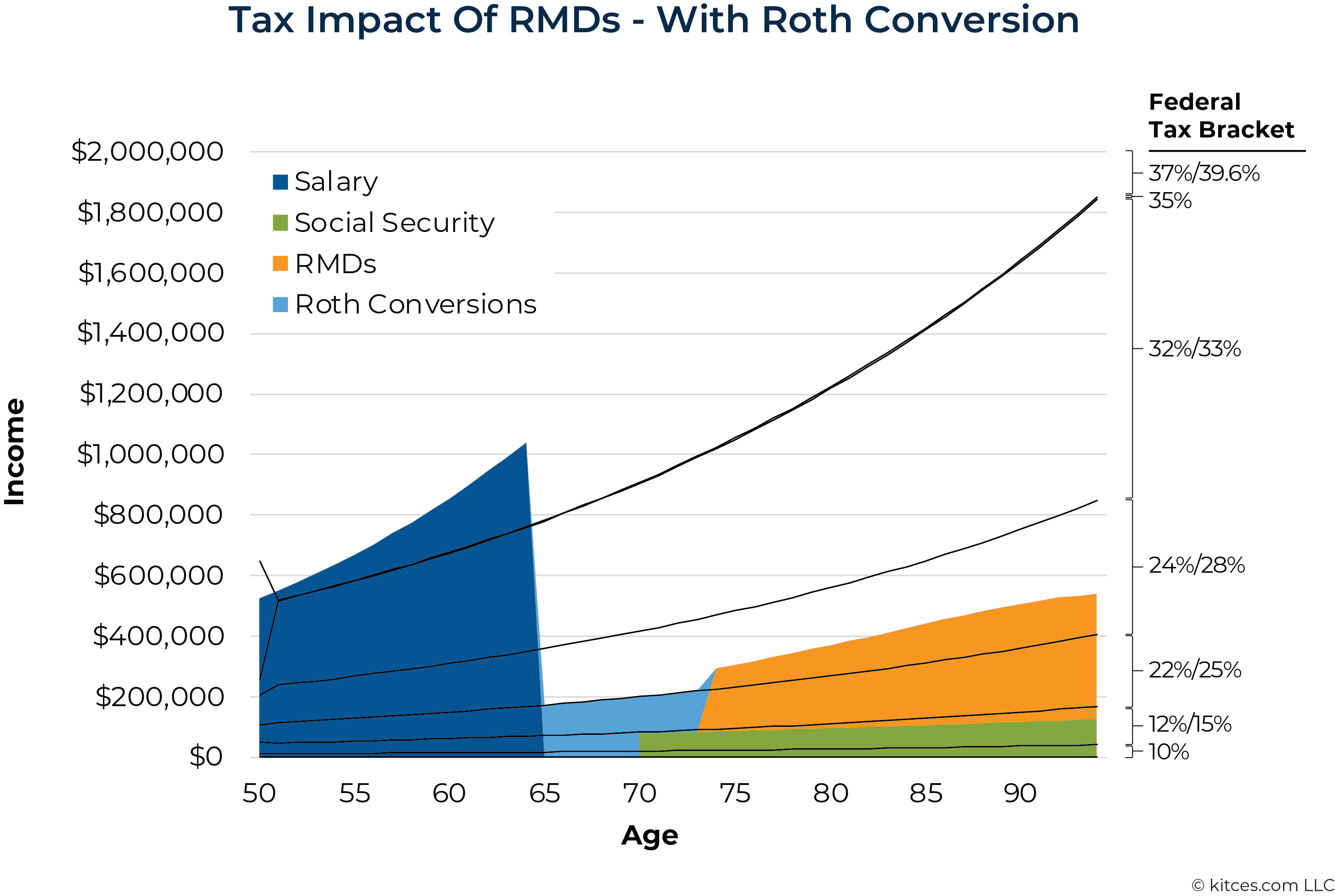

As a person's income fluctuates over time, so does their tax bracket. For example, as illustrated below, a high-earning 50-year-old entering their peak earning years today might decide to retire at age 65, when their income may drop to zero until increasing slightly at age 70 (when they file for Social Security benefits) and more at age 75 (when they take their first RMD from their pre-tax retirement accounts). Over this period, their marginal tax rate could fluctuate from the 39.6% (post-Tax Cuts and Jobs Act sunset) top marginal tax rate just before retirement, to 10% just after retirement, to 24% after claiming Social Security benefits, until finally settling at 28% once RMDs begin at age 75.

The point is that even if tax rates increase at a national level, they'll increase or decrease more on an individual level according to that person's income situation. In the example above, the 5 years between age 65 and 70 represent a time when that person could easily withdraw from their pre-tax retirement account at a much lower tax rate than the rate at which they contributed. In fact, Congress would have to raise the bottom tax bracket up to 39.6% - something that truly would be unprecedented in history – in order to not make it worth contributing on a pre-tax basis, at least up to the amount that can be withdrawn before beginning Social Security benefits at age 70!

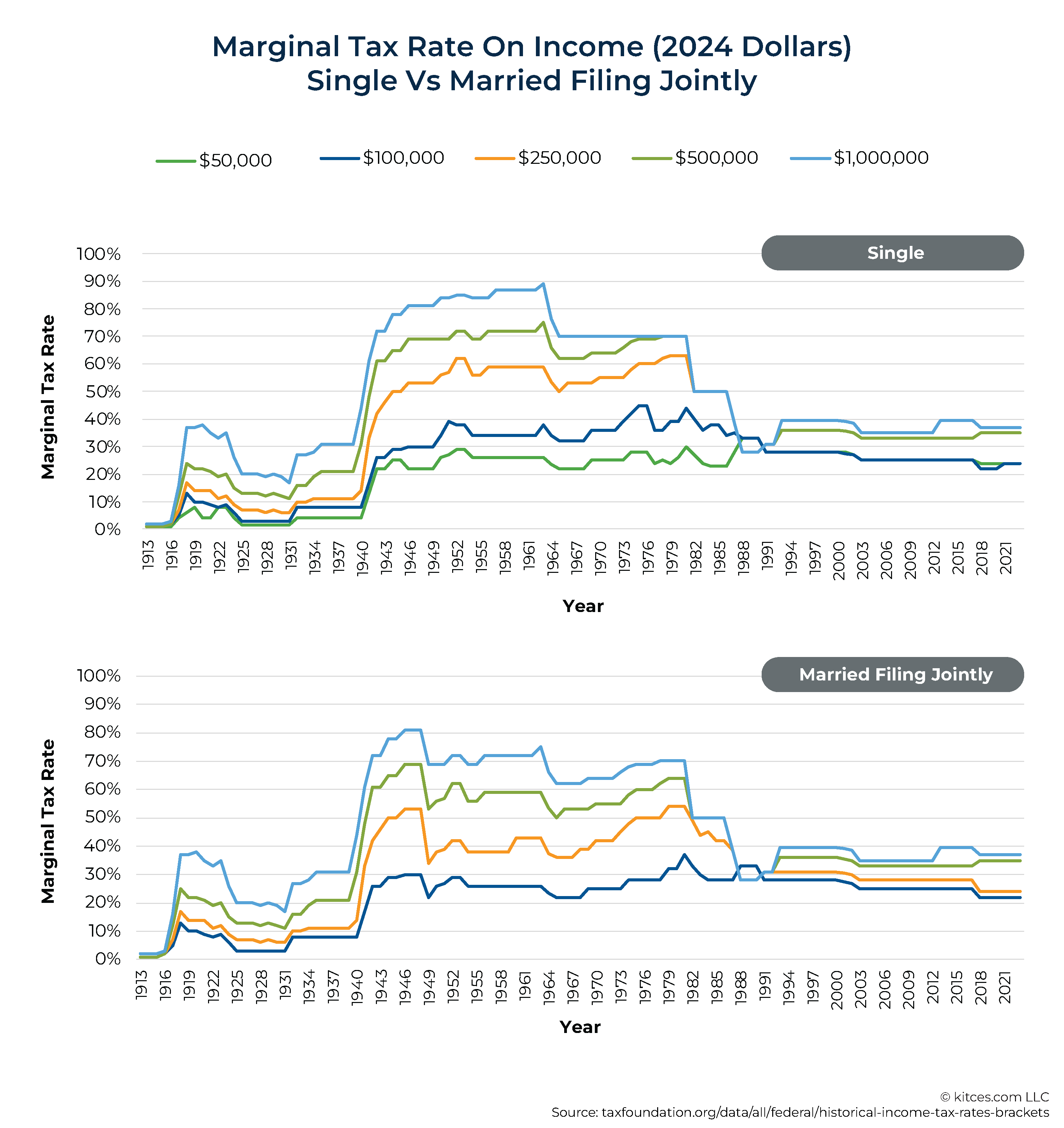

While we can only speculate what future Congresses will do with tax rates, it is worth noting that, despite the large swings in the top tax rate for the highest earners, marginal tax rates have historically been much more stable for those with more moderate incomes.

As shown in the charts below, the marginal tax rate for single filers (top graph) with $50,000 in taxable income and married filers (bottom graph) with $100,000 – both in 2024 dollars – has remained remarkably steady since the start of World War II, hovering between 20% and 30% for all but a small handful of years. The farther someone goes up the income scale, from $250,000 to $500,000, to $1 million – again, adjusted for today's dollars – the more that tax rates have historically swung, and the more they'll likely be affected by future tax increases.

The key takeaway from this historical tax data is that, for someone with a marginal tax rate of over 30% today, contributing to a retirement account on a pre-tax basis would result in withdrawing the funds at a lower tax rate in retirement in the vast majority of historical scenarios, even under the 'worst-case' tax regime in the 1950s and 1960s, as long as they were withdrawn when the person's income level was $50,000 or less (as a single filer) or $100,000 or less (as a married filer).

Put differently, even if you expect Congress to increase tax rates to the levels last seen during the WWII and Korean War eras, it still makes sense for higher earners in their peak earning years to make pre-tax retirement contributions – as long as there's an opportunity to withdraw those funds at a lower income level later on.

Managing Retirement Income Levels To Maximize The Benefits Of Pre-Tax Accounts

If the biggest benefit of contributing to a traditional pre-tax retirement account comes from withdrawing the funds while in a lower tax bracket than when they were contributed, then the main question is how to actually get into a lower tax bracket – and stay there for as long as funds are still being withdrawn.

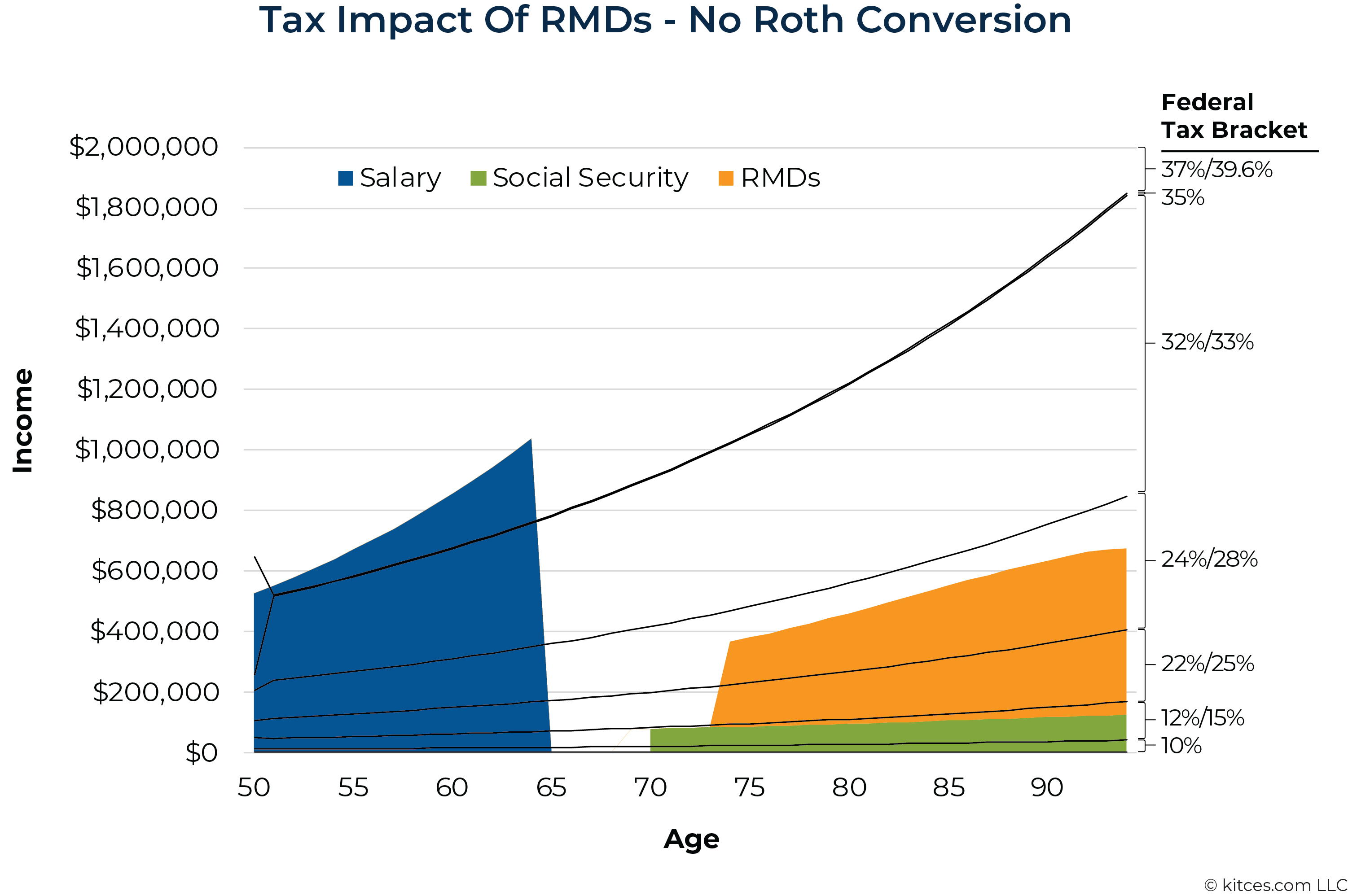

It might seem obvious that a person with a high-paying job will pay lower taxes after they retire, but it isn't always quite so simple, especially if they have large amounts saved away in pre-tax retirement accounts.

First, there will be a base level of income from Social Security benefits, starting at age 70 if the retiree delays filing to receive the highest possible benefit. If that person was a high earner throughout their career, then they'll receive more Social Security income – in 2024, the benefit tops out at $4,873 per month or $58,476 per year. Since Social Security benefits are taxable at up to 85%, a 70-year-old could have up to $58,476 × 85% = $49,705 in income (or $99,410 for a couple) from Social Security alone before even factoring in any other income sources.

Next, owners of pre-tax retirement accounts will need to take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from those accounts, which they may have either already begun at age 70 1/2 or 72 under the pre-SECURE 2.0 Act rules, or will begin at age 73 (if they were born from 1950–1959) or 75 (if they were born in 1960 or later). And because RMDs are based on the size of the pre-tax account, there's no limit to the size of the RMD: The bigger the account, the bigger the RMD will be. For context, a 73-year-old needs to take an RMD of at least $37,376 for every $1 million of pre-tax assets that they own – e.g., if they have $2 million in pre-tax assets they'll need to withdraw $75,472; if they have $3 million they'll need to withdraw $113,208, and so on.

On top of Social Security and RMDs, there's any other income that the retiree might have – interest from savings or money market accounts, dividends or capital gains from taxable investment accounts, income from part-time work or rental property, etc.

So, for someone with a high-earning career, the combination of high Social Security benefits and large amounts of pre-tax retirement savings (which must be withdrawn starting at age 75 at the latest), along with potentially taxable investments and other income, can cause their taxable income in retirement to creep up. And while it may not quite reach the level of their peak working-age income, it could still be high enough to expose them to higher tax brackets, reducing the benefits of having saved in a pre-tax account – especially if Congress does ultimately raise tax rates on higher income levels.

The Roth Conversion "Option" To Be Taxed At Lower Rates

If contributing to a pre-tax traditional retirement account subjects the owner to RMDs that could eventually push them into a higher tax bracket, then why even bother with pre-tax accounts at all – why not just contribute to a Roth IRA or 401(k) plan that isn't taxed on withdrawal and doesn't subject the owner to RMDs?

The most powerful argument for a pre-tax account as a retirement savings vehicle is that it comes with the option to convert the pre-tax dollars in the account to Roth at any time. That is to say, the account owner can choose when they want to be taxed on the funds in the account (which is what happens when pre-tax funds are converted to Roth), and make those dollars tax-free from that point on. Which makes it very useful to have pre-tax funds available to convert to Roth in years with lower-than-normal income, such as the years between retiring and beginning Social Security and/or RMDs. During this time, the funds can be converted to Roth and taxed at a lower rate than they would have been during high-income working years, or in later years when Social Security and RMDs push the owner into a higher tax bracket.

Notably, Roth accounts do not have this option: There's no way to move funds from a Roth to a traditional account and take a tax deduction in a higher-than-normal income year (i.e., the opposite of what someone would do with a Roth conversion). The ability to choose when income is recognized only goes in one direction, from traditional to Roth. So from a tax timing perspective, it's more valuable to have pre-tax funds, with the possibility of converting them to Roth during lower-income years, than to have Roth funds that stay Roth no matter what.

Which is ultimately why, even if tax rates are expected to go up at some point in the future, it can still make sense to contribute to a pre-tax traditional retirement account. Whether or not tax rates increase, the tax timing opportunities to recognize income from pre-tax accounts will still exist. For higher earners, if there's a reasonable chance of having several low- or zero-income years after retirement, it can make sense to defer the recognition of some of their income from a higher-tax year into a lower-tax year by making pre-tax retirement contributions.

Filling Tax Brackets To "Lock In" The Lowest Tax Rates On Pre-Tax Funds

In practice, the point of making pre-tax retirement contributions is not necessarily to hold all of the funds in the account until they're forced to be withdrawn as an RMD, or to leave them to be inherited by a beneficiary who might be required to empty the account within 10 years. Rather, it's to be proactive about using opportunities to withdraw the funds at a lower tax rate.

To do this, it's helpful to have a reasonable understanding of what the retiree's income situation will be once they reach their initial RMD age – that is, when all of their 'mandatory' sources of retirement income have begun. This income can then serve as the benchmark for comparing different Roth conversion strategies.

For example, consider someone who is 50 years old (born in 1974) and single, earning $500,000 per year (exclusive of retirement contributions), with their income increasing by 5% each year. They contribute the maximum possible amount to their traditional 401(k) plan, including employer matches and catch-up contributions ($76,500 in 2024), and already have $1 million saved in their 401(k) account. They plan to retire at age 65 and wait until age 70 to claim Social Security benefits.

As shown below, they're currently in the 35% tax bracket but will bump up to the 39% bracket after the expiration of TCJA in 2026. From age 65–70 they're in the 10% tax bracket with zero income, rising to the 15% bracket with their Social Security income from age 70-75, and finally to the 28% bracket with the onset of RMDs from the pre-tax account from age 75 on.

Notice how the retiree is already getting a 'good deal' from making the pre-tax contribution: They made the original tax-deductible contributions at a 35% and 39.6% marginal rate, and will be withdrawing the funds at a 28% marginal rate, saving them 7% to 11.6% in taxes on the funds in the pre-tax account compared with contributing them to a Roth account.

However, they can do better, because there's a 10-year stretch from age 65 to 75 where they're in a lower marginal tax bracket than 28%. As shown below, if they convert pre-tax funds to Roth during those years to the extent that they've fully filled up the 10%, 15%, and 25% brackets, they can save even more on taxes during those years compared to having contributed to a Roth account while working, which would have effectively locked in a 35%/39.6% tax rate on those funds.

At that point, if they're still concerned about tax rates going up in the future (or about leaving funds behind to their beneficiaries that would be subject to the 10-year rule), they could decide to convert even more funds – at worst, they'd simply be paying the same 28% tax rate on the conversion today (their current marginal rate after filling up the 25% bracket) as they would by withdrawing the funds as an RMD later on. But they could give themselves some peace of mind by locking in that rate today with the Roth conversion rather than leaving it in the hands of a future Congress.

It can feel like a guessing game when deciding between a Roth or traditional contribution even in normal times, and now, with the uncertainty about whether or not (or which portions of) the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act will be extended after 2025, it feels even more risky to try to bet on which direction tax rates will move in the future.

Fortunately, for those in their peak earning years, there doesn't have to be a lot of certainty about the long-term tax outlook, because making a pre-tax retirement contribution is still most likely to work out favorably. And if there's a period of years after retirement where the account owner's income is especially low, the option to convert funds to Roth allows the account owner to lock in the lowest possible tax rate on the pre-tax funds. This gives them more control over how much tax they pay on their retirement savings without having to speculate on what shape the tax code will take in the future.