Executive Summary

While the financial advice industry has transformed in many ways over the past several decades, one aspect that has remained relatively constant is the use of the Assets Under Management (AUM) fee model as a common way for many advisors to get paid. Though in practice, while a 1% AUM fee is a common 'starting point' in the industry, the actual fee structure can vary based on the firm's approach; for example, some firms may reduce the fee for high-net-worth clients, or charge an additional fee for separate and additional services (from deeper financial planning to add-ons like tax preparation).

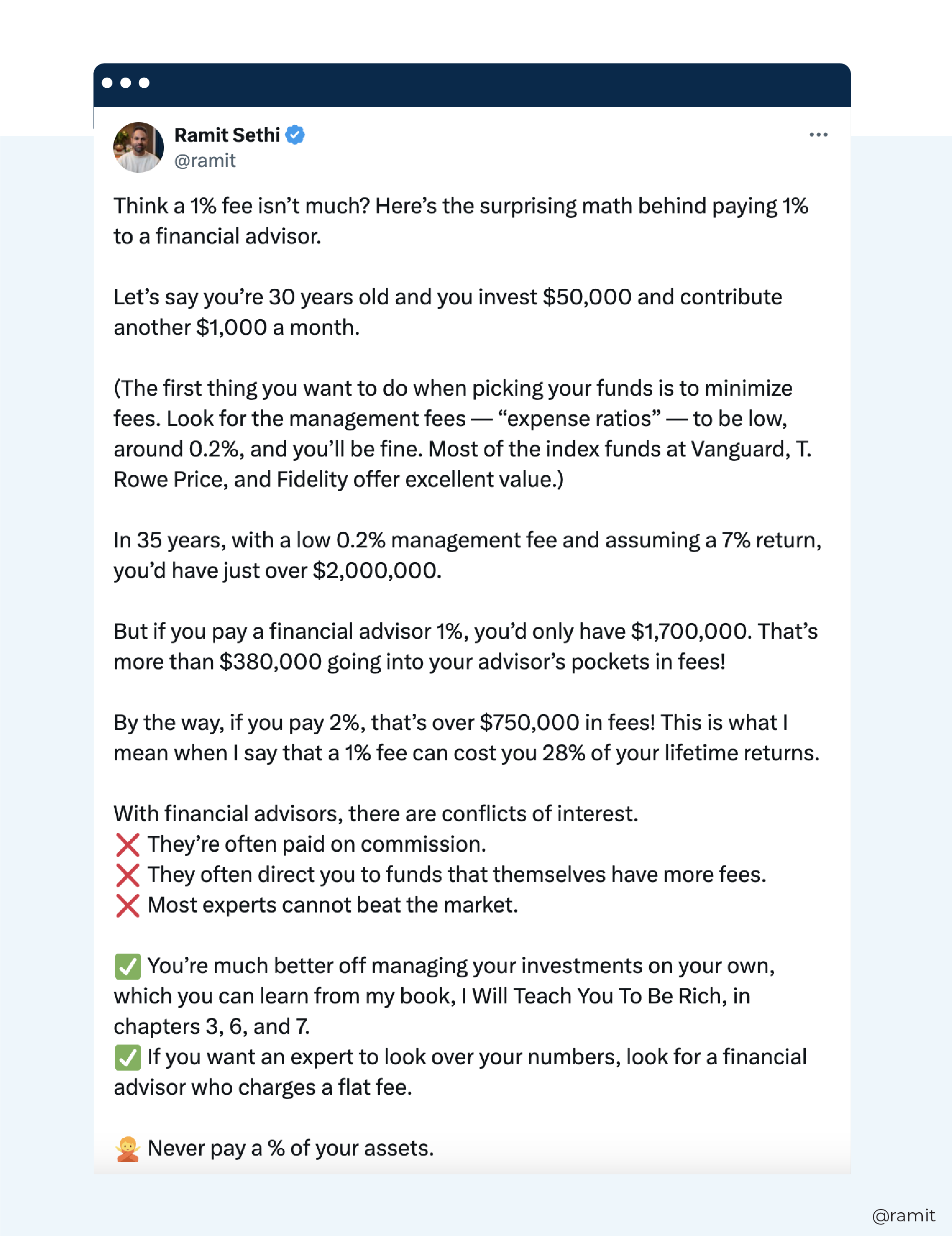

However, over the years, the 1% AUM fee has faced criticism from those who argue that it reduces the value of a portfolio by more than the advisor's guidance adds. This argument is particularly common in the financial independence and personal finance space, with financial educators like Ramit Sethi being a notable critic. AUM detractors like Sethi often present a calculation that compares the performance of 2 identical portfolios – one managed by an advisor who charges a 1% AUM fee for 20+ years, and one without an advisor – illustrating how the fee can significantly erode the cumulative value of their portfolio by the time they reach retirement.

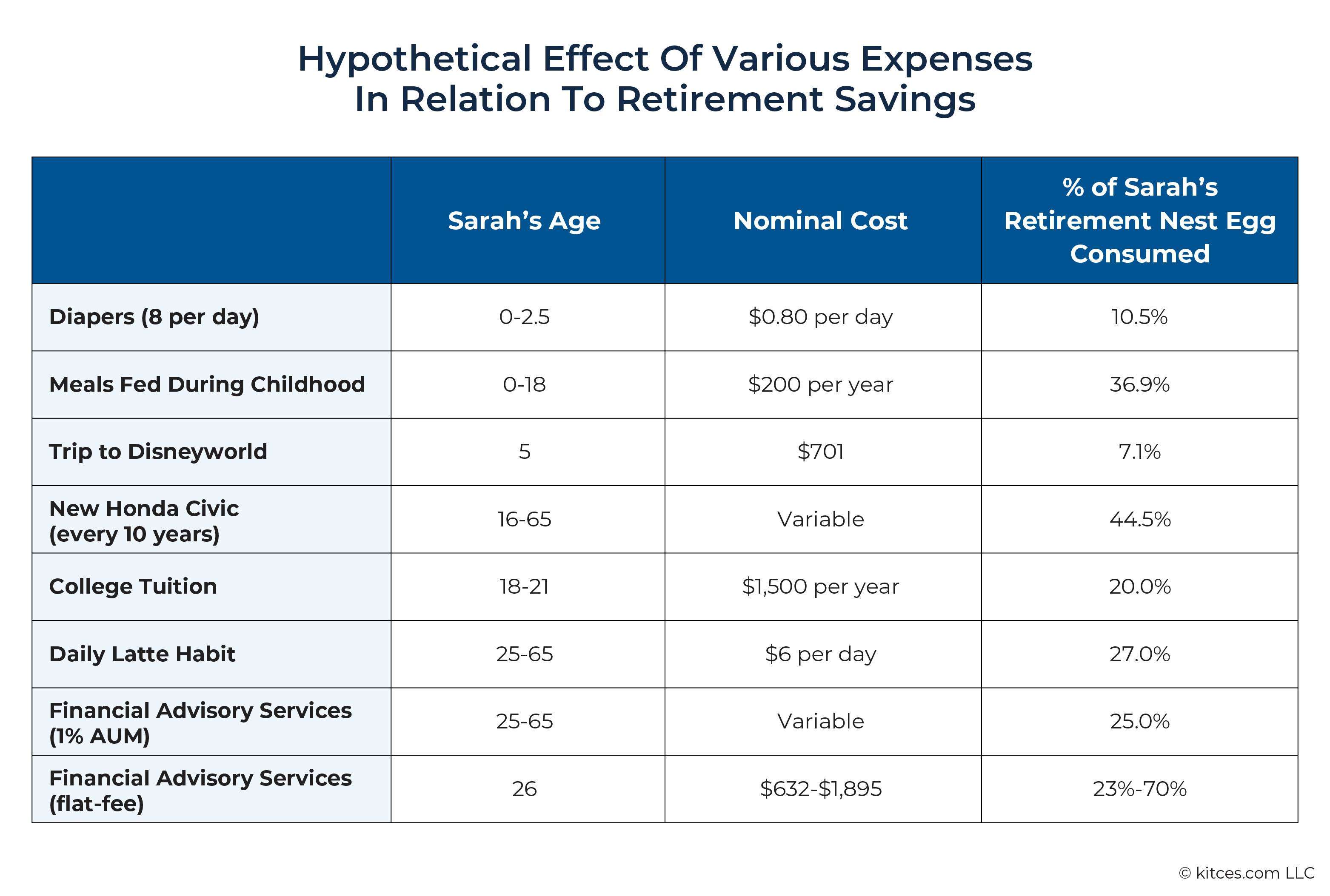

With this line of criticism becoming increasingly common in online financial spaces, how can advisors with a 1% fee structure explain their value to curious (or critical) prospects? One key starting point is to acknowledge that technically, all spending reduces the total amount that a person could have saved and had available for retirement. And almost any 'normal' household expenditure can add up to a lot when it's compounded out, at a market rate of return, for multiple decades. For example, buying a new Honda every 10 years, instead of saving those payments, may take a greater piece of a client's retirement nest egg than a 1% advisory fee. So too does the impact of the infamous daily latte. Comparing expenses to what they could have been worth if saved in a portfolio can be misleading – because from that perspective, every expense seems unfavorable! And in practice, even flat-fee and subscription models of financial planning can still have a similar long-term impact on a consumer's financial future, when only the advisor's ongoing costs are considered.

Additionally, it's worth noting that while Sethi and other financial influencers advocate against the 1% AUM fee, much of their criticism targets those who charge a percentage of AUM but focus more on selling products than on supporting a client's long-term well-being, conflating financial salespeople with actual financial advisors. However, many consumers may not fully understand these nuances of the financial advice industry, and could mistakenly assume that all advisors charging AUM fees operate this way.

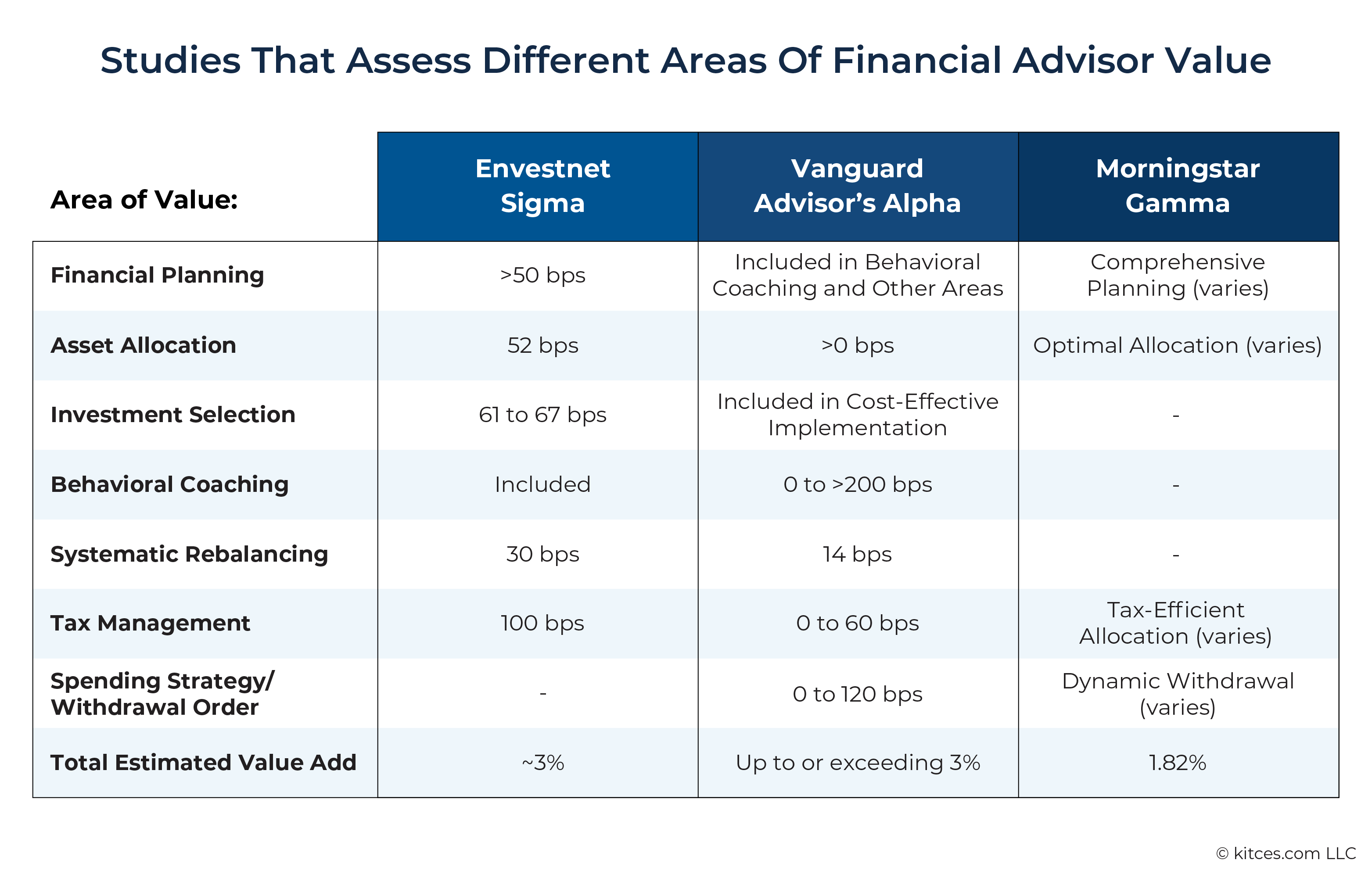

For prospects concerned about long-term AUM costs – and financial advisors exploring the benefits of a financial planning engagement with them – it may be helpful to highlight the value advisors provide beyond 'just' asset allocation. For example, firms that offer services like tax-loss harvesting, systematic rebalancing, and behavioral coaching often more than 'earn' their 1% AUM fee by saving clients money in taxes and other areas. Advisors who can explain their fee in the context of a holistic strategy – and connect it back to the pain points a client faces – can address these concerns before prospects become clients.

Ultimately, the key point is that while criticism of the 1% AUM fee may be widespread, and it's fair to recognize that financial advice does have a cost that advisors should be expected to offset by the value they provide, advisors who lead with holistic financial planning have a lot of value to demonstrate, especially when engaged on an ongoing basis, to help prospects better understand the true costs and benefits of having a trusted financial advisor in their corner!

Ramit Sethi, a prominent personal finance guru known for his bestselling book "I Will Teach You To Be Rich" and his Netflix show "How to Get Rich", has a strong influence on how his followers view financial advisors. He often discourages individuals from working with financial advisors on an ongoing basis, emphasizing the high costs associated with their services (e.g., a 1% AUM fee). To do so, Sethi likes to calculate the lifetime fees someone pays to a financial advisor and express them as a percentage of their prospective retirement nest egg. This approach can lead to some staggering figures that may easily deter people from seeking professional advice. However, there is a mathematical aspect of Sethi's method that is often not recognized.

Ramit Sethi, a prominent personal finance guru known for his bestselling book "I Will Teach You To Be Rich" and his Netflix show "How to Get Rich", has a strong influence on how his followers view financial advisors. He often discourages individuals from working with financial advisors on an ongoing basis, emphasizing the high costs associated with their services (e.g., a 1% AUM fee). To do so, Sethi likes to calculate the lifetime fees someone pays to a financial advisor and express them as a percentage of their prospective retirement nest egg. This approach can lead to some staggering figures that may easily deter people from seeking professional advice. However, there is a mathematical aspect of Sethi's method that is often not recognized.

Sethi's method assumes that a person's investments would earn the exact same whether they work with an advisor or not. Setting aside the 'questionableness' of that assumption, Sethi's approach effectively means he is inflating past management expenses at a rate equal to assumed market returns. But why? Is this an appropriate rate?

This does create eye-popping numbers that could shock and persuade, but, as it turns out, this is not a reasonable method for estimating the long-term cost of services provided by the advisor (or really, the long-term cost of any goods or services we purchase). By inflating past expenses at market rates, the approach creates an exaggerated sense of the financial burden imposed by advisors. This practice not only confuses individuals about the true costs of working with an advisor, but also disregards the potential offsetting positive value that advisors can provide.

A closer examination reveals significant mathematical and practical flaws in this approach, which we will explore in this article.

Understanding Sethi's Method To Evaluate The Impact Of Financial Advisors' Costs

At the heart of the issue with how Sethi calculates and talks about the costs of working with an advisor is that he doesn't just reference the actual fees someone pays to their advisor. Rather, he looks at the difference between 2 identical portfolios, with and without an advisory fee. Setting aside the fact that it is highly unlikely that fund selection, rebalancing, asset allocation, asset location, and tax loss harvesting are going to look identical between a portfolio managed by an advisor and one managed by a DIY investor, this means that Sethi is not only calculating what someone paid, but is also inflating and compounding fees paid over time at a rate of return equal to the market return. Then, it is these future values that Sethi compares.

Consider the Tweet below where Sethi walks through a very typical calculation of his:

As we can see, Sethi is looking at the difference between the future value of a $2,000,000 portfolio and a $1,700,000 portfolio, and then using that for his basis that someone paid more than $380,000 in fees (differences due to rounding) and, ultimately, a large percentage of their retirement nest egg.

Importantly, the individual in this case didn't actually pay their advisor $380,000. Over the course of 35 years, they paid their advisor a cash flow stream that, if it had been invested in the market earning a full 7% return, would have been worth $380,000 going out 35 years into the future. In practice, by Sethi's methodology, the client would have actually paid cumulative fees of less than half this amount – about $167,000 – spread out over 35 years (or less than $5,000 per year, and averaging only about $1,000/year of actual fees paid across the first decade).

The Deceptive Nature Of Inflating Past Expenses Into Future Growth Values

Anyone familiar with compound interest should start to see where the confusion comes in here. By applying market rates to past financial advisor fees, the perception of the true cost is exaggerated into what those expenditures might have grown in to.

To illustrate, imagine that we do the same type of calculation but apply it to all sorts of other mundane household expenditures. To keep things simple, we will use a slightly modified example (as unrealistic as this example is, bear with me here):

Example 1: Sarah is currently 65 years old and has been saving an equal amount for the past 40 years so that she could retire at age 65.

Sarah decided she would save an annual amount of $3,860.15 since this would give her a nice round $1,000,000 by age 65 by earning 8% in the market as a DIY investor.

In the example above, Sarah has done a nice job saving and built up her $1,000,000 retirement nest egg by age 65. However, let's consider what would have happened if Sarah had worked with an advisor who was charging a 1% AUM fee.

Example 2: All of the details remain the same as in Example 1, except now Sarah worked with an advisor who charged a 1% AUM fee.

Assuming the portfolio and returns were otherwise identical, Sarah now arrives at retirement with a nest egg of only $747,363, which, by Sethi's methods, would suggest that she 'paid' her advisor $1,000,000 – $747,363 = $252,637, which is more than 25% of her entire retirement nest egg that went to her advisor!

Sounds alarming! Why would Sarah want to 'pay' over 25% of her nest egg to her advisor?!

But let's consider applying these same methods to some other expenses that Sarah incurs. In fact, let's go all the way back to when Sarah was in diapers – literally.

Example 3: Let's assume that when Sarah was born in 1959, a diaper cost $0.10. Additionally, let's assume that Sarah went through an average of 8 diapers per day for the first 2.5 years of her life, and that diapers experienced inflation of 3% per annum over this period.

In nominal terms, these costs probably don't sound life-changing. While not cheap, the nominal cost still comes in at under $750. However, we're not here to simply talk in nominal terms. Instead, we'll use Sethi's method of assuming that little baby Sarah would have invested all of these dollars in index funds (earning 8%) had it not been for her parents wasting it on silly diapers.

In doing so, we see that the cost was not $750 total in the early 1960s, but rather, a whopping $104,633 in 2024! In other words, Sarah's diapers cost her an equivalent of 10.5% of her entire retirement nest egg.

Who knew the Diaper Industrial Complex had such a stranglehold on the wellbeing of retirees?!

Now, readers might object, "Derek! You've totally ignored the benefits those diapers provided." Yes, but we need to be consistent with Sethi's method. The assumption here is that zero value was provided by whatever expense was incurred, so we're simply being consistent in applying that to other expenses one may encounter.

Moreover, we can see how not just diapers but all sorts of other expenses wreak havoc on our financial security for retirement.

For instance, consider the following:

- 7.1% of Sarah's retirement nest egg was eaten up by Sarah's parents taking her and her sister to Disneyworld when she was age 5 (cost of $710 in 1964).

- 20.0% of Sarah's retirement nest egg was eaten up by attending college at a cost of $1,500/year from ages 18–21.

- 27.0% of Sarah's retirement nest egg was eaten up by a career-long daily latte habit from ages 25–65 ($6 per latte in 2024 dollars).

- 36.9% of Sarah's retirement nest egg was eaten up by Sarah's parents feeding her from age 0–18 ($200/year beginning in 1959 inflated at a rate of 3% per annum).

- 44.5% of Sarah's retirement nest egg was eaten up by purchasing a Honda Civic once every 10 years beginning at age 16 (prices as of the year of purchase).

Of course, we could go on and on with silly examples. The Honda Civic example is particularly striking. Would we really argue that purchasing a modest car every 10 years is an outrageous expense? For lifelong used car buyers, perhaps it can be seen as a bit of a luxury, but to inflate this cost by the rate of the market (rather than inflation) and then express it as a percentage of Sarah's retirement nest egg paints a really distorted picture of what she was paying and the value she was getting from her vehicle.

To give another example, let's consider a hypothetical scenario in which Sethi was teaching his course, "6-Figure Consulting System", at the time Sarah was turning 25. Perhaps Sarah was an aspiring 6-figure consultant, so she saved up some of her money and decided to enroll in Sethi's class.

Example 4: Per lead generation advocate Ippei Kanehara, Sethi's course currently carries an initial cost of $1,564 and a monthly cost of $797/month for a minimum of 12 months. Sarah, from our earlier examples, enrolls and stays enrolled in this course for 3 years.

Since we are assuming this hypothetical course happened in the past, let's make an inflation adjustment using CPI and adjust this cost back to 1984–1986 dollars when Sarah would have been in her mid-20s when she'd be most likely to have taken the course. In nominal dollars, Sarah pays a total of roughly $10,827.

However, since we're using Sethi's own method to inflate the cost by market returns and compare that result to her retirement nest egg, the total cost of Sethi's own course to Sarah ended up being a whopping $218,655, which amounts to almost 22% of Sarah's retirement nest egg!

Wow! Just 3 years of taking Sethi's course could cost someone 22% of a $1 million nest egg? How does Sethi sleep at night?! 😉 😉

Snark aside, one last salient example here would be to compare the cost of AUM services against the cost of financial planning services Sethi recommends. Notably, on Sethi's website, last updated on April 3, 2024, he states that advisors can be helpful as a 'temporary second set of eyes' and suggests that consumers should look for advisors who charge an hourly or project-based fee. More recently, Sethi began a paid endorsement relationship with Facet Wealth, which provides ongoing advisory services ranging in cost from $2,000–$6,000/ year. For instance, Sethi states the following in a Facebook video:

There's a much better way [than AUM] if you truly decide you want a financial advisor, and that is to pay an hourly or project rate. A lot of you have been asking me, "Where do I find a financial advisor like that?" That's why I partnered with Facet – a service that offers affordable, accessible financial planning.

Notably, Facet Wealth's ADV Part 2A, as of July 22, 2024, indicates that Facet does not provide hourly or project services that would be 'temporary' in nature and, instead, provides ongoing subscription services. Nonetheless, since Sethi is accepting compensation from Facet and publicly endorsing them, we can presume he is also endorsing the ongoing flat fee (non-AUM) model as well.

As such, we'll repeat a similar analysis for Sarah comparing the costs of flat fee services at both the low-end ($2k/year) and high-end ($6k/year) of Facet's service offerings. Furthermore, we'll adjust the flat fee pricing based on the same assumed inflation rate of 3% per annum that we have used for other goods and services in this article, anchored to a 2024 price of $2k or $6k (i.e., in Sarah's first year of working with a flat-fee advisor – 1986 at age 26 – she would have paid a nominal fee of $631.51 in the $2k scenario and $1,894.52 in the $6k scenario).

Recall that using Sethi's method for assessing the cost of AUM services, 25% of Sarah's nest egg "went to her advisor." Using this same method to assess the cost of flat fee services that Sethi endorses, Sarah would have a nest egg $233,184 smaller in the $2k annual expense scenario, and $699,551 smaller in the $6k annual expense scenario. To express these in percentages of Sarah's retirement nest egg as Sethi does, the cost of a $2k annual subscription with Facet would cost Sarah 23% of her nest egg, and Facet's $6k annual subscription would cost her 70% of her nest egg.

We can summarize all of the numbers we've looked at here in the following table:

To be clear, the point here is not that anything presented above is a reasonable way to look at long-term costs – it's not! The point is that inflating costs into the future at market rates and quantifying them as a "percentage of your nest egg" the way that Sethi does is a misleading way to think about expenses that we incur in the first place.

That being said, even doing so in the specific context of advisory fees, we see that AUM is not tremendously more expensive than flat fee services at the levels examined here. Rather, the cost in this scenario came out to be effectively the same in the $2k annual subscription model and significantly less expensive in the $6k annual model.

And in the context of other expenses, we see the "nest egg" costs of hiring an AUM advisor as quite similar to a daily latte habit. Of course, that doesn't sound anywhere near as scary and won't sell any books, but it is not a wise way to look at costs in the first place.

In fact, savvy readers will notice that just the short list of a few of Sarah's potential expenditures during her lifetime already add up to more than 100% of her entire nest egg… because ultimately, Sarah's nest egg is built around only what she saves, which itself is a percentage of her total income. If on average Sarah is saving 10% of her income and living off the other 90%, than in any particular year, Sarah's mere efforts to maintain her standard of living and pay her household expenses is already costing her 900% of her retirement nest egg per year by Sethi's methodology!

The Fallacy Of Assuming Advice Has Zero-Value

The examples above were all meant to illustrate why inflating expenses into the future at an assumed market return, and then comparing that to (just) a retirement nest egg rather than the household's entire spending, is a mathematical practice that can make current expenditures seem outsized, even if it were true that no value was received in exchange for a good or service.

However, the even more glaring issue with Sethi's method is his assumption that zero value is received in exchange for the dollars paid to an advisor (or any other good/service).

Surely, Sethi would object to this assumption being applied to his own courses. He aims to help people, and if Sarah committed herself to his course and found it worthwhile to continue receiving his guidance for 3 years, it is likely she was getting real-world benefits from his course that she perceived to outweigh the cost. Even just bringing in an extra $5k worth of consulting profits for the years she was enrolled in his consulting course would already have been a nice return on investment (never mind the potential long-term benefits if his course set her on a path that saw that growth sustained over her career) that far outweighs "spending 22% of her retirement nest egg on a Ramit Sethi course".

To get more specific to the context of financial advisors, the point here is certainly not to say that there is value in working with every single advisor. In fact, it is also possible that some advisors/strategies could destroy value over time – consistent with some of the fair criticisms of advisors Sethi does have, such as salespeople who are not actually in the financial advice business and are just trying to sell high-cost financial products and provide little or no actual financial planning to their clients. (Though we wish he would do more to separate "financial salespeople" rather than conflating them with others who are actually in the business of being "financial advisors" providing and compensated for financial advice itself.)

And there certainly could be circumstances where very knowledgeable DIY investors with utmost confidence in the index funds they've chosen and nerves of steel can invest all of the way until retirement without flinching. Furthermore, it is also possible our perfect DIY investor runs into an advisor who only provides investment management and never provides a single tax or other financial planning recommendation (or worse; the advisor could steer the advisor toward strategies such as excessive turnover that destroy wealth relative to the DIY investor's index fund approach).

But the zero-value assumption fallacy is only going to hold here if both of the items above are true. If we are talking about 'good' advisors, who are actually in the business of delivering financial planning advice, it is highly unlikely that a DIY investor who does not otherwise engage in financial planning professionally is going to make it through 40 years of working with an advisor and never receiving anything of value. Even financial advisors who use a 'VTSAX and chill' or other comparably simple investment approach are likely to be focused on other areas of financial planning that can add financial value.

Moreover, for many real-world consumers who aren't going to satisfy the perfect DIY behavior described above, there are likely lots of opportunities for good advisors to add value. Studies such as Vanguard's Advisor Alpha, Morningstar's Gamma, and Envestnet's Sigma have estimated the value of good financial planning to be somewhere in the range of 1.5–3.0% per annum.

But even if advisors only provide a fraction of this, it will at least eat into the true net cost that an individual experiences by paying a financial advisor, if not provide a net value that more than covers the advisor's fee.

Nerd Note:

There's an interesting corollary to Sethi's approach of quantifying the costs of AUM advisory services. If one inflates the costs at market rates into the future, then ostensibly one should do the same for the benefits. For instance, if an advisor implements an asset location and/or tax-loss harvesting strategy that an individual would have been unlikely to implement themselves and generates a 1.0% tax alpha net of their advisory fees each year, then this alpha would actually compound into the future at market rates, potentially enhancing the benefits of working with an advisor even more than might be otherwise captured when looking just at annual costs/benefits (with the advisor increasing the retirement nest egg approximately 28% in this scenario by Sethi's methodology).

In the context of tax management and other strategies directly related to after-tax portfolio returns, this is also a relatively fair comparison in the same way that using Sethi's method to compare 2 otherwise identical S&P 500 funds would be a fair comparison. However, the value advisors provide in other areas of financial planning become more mathematically difficult to assess in this type of framework. For instance, suppose a financial advisor recommends a tax strategy that reduces one's tax liability by $5k in the current year, and those tax savings are used to fund a family vacation. In this case, there's again no logical basis for inflating the value of services received forward at market rates or otherwise, though clearly the additional family vacation has real value (even if it's not part of their retirement nest egg).

One aspect of the earlier example of the cost of food for Sarah's parents to feed her during childhood that made it so obviously silly was that it is very clear that there is value as well as cost. Using Sethi's methods, it did cost Sarah 36.9% of her retirement nest egg to be fed from ages 0–18, but what other choice did she have? She needed to eat. And while it is almost certainly true that Sarah could have survived that period on less food than she consumed, does it even make sense to contemplate that Sarah could have added another 7.4% to her retirement nest egg simply by eating 20% less from ages 0 to 18? No, it doesn't. It's simply very arbitrary to inflate her expenses by the rate of the market and then compare that to her retirement nest egg – just as it is when comparing the cost of diapers, lattes, school, Sethi's course, or even financial advisors.

Ramit himself is a proponent of the "Live Your Rich Life" framework and argues it is okay to spend on things that you want to spend on and that are meaningful to you. Presumably, that would also apply to the confidence and peace of mind that someone might get from working with a financial advisor? Especially since, as the examples note here, Sarah's AUM advisory cost – as a percentage of her nest egg – is not substantively different, and may even be cheaper, than the flat-fee alternative that Sethi endorses.

Additionally, as with any consumer purchase, there are subjective or harder-to-quantify aspects of 'value' to deal with as well.

I could potentially watch hours of YouTube videos and try to do an electrical wiring project in my house all by myself. This would save me the cost of an electrician. But this also means hours of time invested in something I don't enjoy (non-pecuniary cost), hours of time not invested in activities that may have been more profitable for me (opportunity cost), and a potential lingering fear/uncertainty of the consequences that could arise if I made a mistake that I'm not aware of (house-fire cost).

When it comes to portfolio management, specifically, this latter factor can be worth a lot more than may be initially appreciated. If someone trusts their advisor and has peace of mind that their advisor is staying on top of building the best portfolio for them, that potential source of anxiety can be released and they can devote that energy more productively in their life – whether that's in their own career, family, causes they care about, or whatever else is most important to them. Even the best DIYers still often have lingering doubts about their approach, and this is why it is not at all uncommon for DIYers to seek out advisors for second opinions.

How Should Consumers Think About The Cost Of An Advisor?

As we think about different ways that consumers can intelligently assess the value of working with a financial advisor, we can make 2 broad observations about Sethi's approach.

First, even if a consumer is going to get zero value from working with a financial advisor, the approach of quantifying the costs of goods/services inflated at market rates, and as a percentage of one's retirement nest egg, is not a good method for assessing costs. As adding up the full range of a household's ongoing expenditures would offset more than 100% of their retirement nest egg each year under such an approach (given that even almost all households that save still spend far more than they save each year).

Second, unless zero value is truly derived from a good/service, the value side of the equation must be considered when assessing long-term costs. While Sethi's approach may be appropriate for comparing, say, costs between 2 different S&P 500 funds (since, in this case, they are doing the exact same thing and there is no value to a higher cost, it just drags down returns), it is not appropriate to be applied to most financial advisors.

However, it certainly is true that consumers should be mindful of costs when considering working with an advisor. The trio of studies referenced above (Vanguard's Advisor Alpha, Morningstar's Gamma, and Envestnet's Sigma) all provide attempts to quantify various aspects of working with advisors. And the reality is that no 2 individuals are going to get the same value from these different areas. These are merely attempts at broadly assessing the value a consumer might receive in their particular circumstances (even though ultimately, circumstances will obviously vary).

For instance, an investor who knows nothing about asset allocation and investment selection and has no desire to study these topics might receive 100 bps or more of value from these areas (as estimated by Envestnet's Sigma), whereas an investor who has already read multiple books on these topics and feels pretty comfortable with their approach might receive little incremental value from a financial advisor there.

Likewise, someone who has a history of getting uncomfortable and wanting to jump out of investments when the market declines might receive 200 bps or more from behavioral coaching (as estimated by Vanguard's Alpha), but an investor with a great long-term orientation who actually gets excited to save more during market dips may get close to zero benefit by engaging a financial advisor to help with that domain.

One place a savvy consumer might start is by synthesizing the various studies available and trying to find some commonalities between them.

For instance, consider the following chart:

When trying to assess how valuable (or not) financial advising services are for a particular individual, someone might think about how their needs may or may not align with the categories identified in the table above.

Additionally, consumers generally may want to consider how well an advisor's own expertise and background may align with their particular needs. For instance, if an advisor specializes in working with executives from a particular company (e.g., Microsoft), it is very likely that an executive from Microsoft would get more value from working with that advisor than an executive from another company like Exxon Mobil (and this advisor may be more valuable to the potential client than other advisors without that specific knowledge relevant to their situation, as this often opens up many doors to better financial planning, tax planning, etc.).

While it can be hard for most consumers to assess an advisor's competence (just as it would be hard for a non-surgeon to assess the competencies of a surgeon), in a financial planning context, one strategy consumers might want to consider when interviewing advisors is to do homework on at least a few niche areas of their own situation and see how familiar (or unfamiliar) an advisor is with that niche.

To continue the executive example above, a few well-crafted questions could be quite insightful in terms of how much an advisor actually knows about a particular company. For instance, an executive might consider asking, "What are your thoughts on the change in our stock compensation plan that happened last year?"

Assuming the executive has at least brushed up on this change, an advisor's answer to this question can be very telling about their actual expertise. If an advisor is very well versed in the company and their compensation plans, then they should be able to easily provide an answer with a good degree of detail about the questioned change and how it has impacted other executives. However, if the question catches an advisor flat-footed, they probably don't have the expertise or specialization that they've perhaps claimed.

Furthermore, the absolute worst-case scenario would be for an advisor to not know an answer to a question like this and try to make something up by faking their way through it. There is a lot to master when it comes to financial planning; even well-versed advisors may need to say, "I don't know". While that's not necessarily a reason to stay away from someone, pretending to know something that one doesn't know is definitely a red flag when evaluating a potential financial advisor.

Why Sethi's Advice To Avoid AUM (Or Other Ongoing Fee Advisors) Could Be Harmful

Sethi doesn't actually suggest that consumers should never work with financial advisors. Rather, he has historically said that consumers should only work with advisors on an hourly or other one-time fee basis. Recently, Sethi seems to have expanded that to allow for ongoing subscription models like Facet (which he now has an outright compensated endorsement arrangement with).

This may be a positive shift, but, as noted previously, the long-term 'costs' of subscription services like those that Sethi endorses don't necessarily fare any better when using Sethi's nest-egg cost assessment (and could even fare much worse). But the point here, again, is not to suggest that this is a good method for valuing services – it's not! – but to look at why his approach to thinking about long-term costs could nudge someone away from ongoing advice services in general (whether paid by AUM or flat/subscription fees).

And this is problematic because another consideration regarding getting the most value from working with an advisor is the nature of one-time versus ongoing consulting, and the degree to which either approach can actually provide the types of services that studies have indicated are most valuable when working with advisors. Furthermore, there is also some relationship between the level of expertise advisors have, and the service models they offer.

First, let's consider an advisor's ability to deliver on areas such as behavioral coaching, tax management, and ongoing financial planning, which have generally been identified as the most valuable types of services that advisors can provide.

One challenge with actually delivering these services through a one-time plan is precisely the fact that it is a one-time plan – and it is unlikely that the moment the one-time plan is carried out is the same moment when the guidance is actually needed. For instance, behavioral coaching is most valuable when someone has reached their breaking point in terms of tolerating risk as they watch their account balance dwindle in a market decline. No one knows in advance when that will occur, and, anecdotally from my experience, even DIY investors who have never been bothered by market downturns in the past can start to get spooked when big life changes (e.g., retirement) are on the horizon.

It is one thing to go through a downturn when you love the company you work for, your job is secure, and you can't imagine making any changes in the next 10 years – but it's an entirely different experience when you are thinking about stepping away to take on an entrepreneurial endeavor or fearing the possibility that an economic downturn could also claim your job and lead to an indefinite period of unemployment. That uncertainty can shake the confidence of even the most (previously) steely-eyed investors. But that most likely is not the moment that the investor may have otherwise engaged a financial advisor for a one-time comprehensive financial plan?

Likewise, tax planning opportunities can arrive suddenly and be very transient in nature. Perhaps a special bonus depreciation opportunity comes up for business owners in a certain field, the market declines and a tax-loss harvesting opportunity arises, or maybe someone has significant tax losses from a business startup and never thought about the potential to pair that with a Roth conversion. The list could go on and on regarding tax planning opportunities that come and go, but the key point is that a one-time plan generally can't identify most of these opportunities as they arise in real-time as the future unfolds.

Moreover, the ongoing nature of a more-than-temporary advisory relationship allows a professional to understand a given client's situation and better identify opportunities that may subsequently come up along the way. Advisors can only get to know a client so well through a one-time engagement, but after years of working together and learning about family, charitable interests, business activities, hobbies, etc., a better foundation is set for a good advisor to be able to identify emerging planning opportunities or to counsel through difficult and complex situations. Not unlike how healthy individuals may simply see their doctor periodically for a physical, but when health complications arise, we tend to seek out a more established and ongoing relationship with a doctor who understands the full scope of our medical history and how the condition has evolved and responded to treatment over time.

The value of a strong relationship with a particular advisor can also be seen in areas such as monitoring for elder abuse or other abusive financial relationships. If an advisor knows that a client is set up to take $10k per month in retirement and hasn't deviated from their normal distribution in years, then a sudden shift in behavior and requests to withdraw an extra $20k, $30k, or more in a given month could set off red flags that something is amiss. The likelihood of catching this type of abuse before it is too late is extremely low for someone who is engaging an advisor periodically for one-off reviews, and if their capacity has dropped to the point that they are being taken advantage of, the chances of them even continuing to engage an advisor for one-off reviews is also extremely low.

Nerd Note:

There is an interesting exchange between Michael Kitces and Ramit Sethi on the precise topic of the value of ongoing relationships and the rationality of a 1% AUM fee beginning at the 43:21 mark of Episode 301 of the Kitces Advisor Success Podcast. At 51:45, Sethi poses a question to Kitces regarding whether he would allow his own parents to pay a 1% AUM fee, and Sethi seems quite surprised to learn that Kitces' parents actually do pay a 1% AUM fee, despite the fact that Kitces is also the co-founder of XY Planning Network, a support platform that helps to launch flat-fee subscription-based financial advisors more aligned to Sethi's own advisor-fee philosophy.

Another potential concern with Sethi's "nest egg cost methodology" that could push consumers to focus on working with advisors on an hourly or project-type basis is the segment of advisors this is going to push consumers towards. Now, to be clear, there are great advisors who work within all business models, but, generally speaking, advisors who are really great at what they do and who can deliver a lot of value to their customers tend to gravitate toward ongoing relationship models (because when you're a service-oriented professional, it's enjoyable to have a dedicated base of clientele that you can serve more deeply in an ongoing relationship).

Notably, this doesn't necessarily mean advisors gravitate toward AUM models (they could also offer flat-fee or other subscription-type models as Sethi promotes with Facet), but an advisor's prices and minimum annual expenditures to work with that advisor do tend to go up as their business grows and they gain more experience and expertise.

As a result, it is not uncommon at all for advisors who are just starting out (and who desperately need any finanical planning engagement revenue to keep their business alive) to be open to hourly and project-based work. However, a very common pattern among advisors is that as they gain experience and build their client base, they also begin to drop hourly and project-based work as an offering and work solely with clients on an ongoing basis.

Notably, this willingness to provide hourly or project-based services is going down at precisely the time when the type of wisdom and experience that allows advisors to be most effective is going up. Which means consumers who are solely focused on finding an hourly or project-based planner consistent with Sethi's recommendation could also be unwittingly filtering out many of the advisors who could be the most valuable to them (and avoiding the structure of working relationship that provides the best opportunity to capitalize on the areas of financial planning that have been identified as the most valuable areas of planning), unless they can specifically find one of the relatively few hourly advisors who has been operating under such a model for a long time and brings that deeper level of experience.

While Ramit Sethi's approach to calculating the long-term costs of financial advisors (in particular, those who charge an AUM fee) is certainly attention-grabbing, it significantly distorts the true financial picture of working with an advisor. By inflating past fees at market rates and ignoring the potential value financial advisors can provide, Sethi's method paints an alarming and potentially misleading picture, including in situations where an advisor's AUM model might be less expensive than alternative fee models.

This method also fails to consider the myriad of benefits that competent advisors can offer, from optimized asset allocation and tax strategies to crucial behavioral coaching during market downturns. Just as it would be unreasonable to retroactively inflate the cost of everyday expenses at stock market rates of return to make them appear exorbitant, it is equally misguided to apply such calculations to financial advisor fees without acknowledging the value that at least can be received in return (when the consumer finds the right-fit advisor).

Moreover, the zero-value assumption inherent in Sethi's calculations overlooks the real-world advantages that many clients experience when working with knowledgeable advisors. Studies from sources like Vanguard, Morningstar, and Envestnet suggest that good financial advice can add significant value, potentially exceeding the cost of advisory fees. For many individuals, especially those who are not well-versed in investment strategies and financial planning, the expertise and guidance of a professional advisor can result in better financial outcomes and peace of mind. Ignoring these benefits and focusing solely on costs presents an incomplete view of financial advisory services.

Ultimately, consumers should approach the decision to hire a financial advisor with a nuanced understanding of both costs and benefits. While it is clearly wise to be mindful of fees and to seek advisors who provide clear value, it is also important to recognize that the best advisors offer more than just investment management; they provide comprehensive financial planning that can enhance overall financial well-being. By considering their own unique needs and seeking advisors with proven expertise in those areas, consumers can make informed choices that align with their long-term financial goals.