Executive Summary

(Note: For an updated discussion on the 2025 "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" which extended and replaced TCJA, see Breaking Down The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act”: Impact Of New Laws On Tax Planning)

With Republicans appearing to have secured a sweep of the White House and both chambers of Congress, the most immediate question for many financial advisors and their clients is what impact the election results will have on the scheduled expiration of the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA) at the end of 2025.

At a high level, the Republican trifecta would appear to set the stage for much of TCJA to be extended beyond the original 2025 sunset date. However, with the makeup and priorities of the incoming Congress differing from those in 2017 – and with President-elect Trump having made numerous promises for new tax cuts on the 2024 campaign trail – there will inevitably be portions of the existing law that Congress will aim to amend or even expand beyond the original tax cuts created by TCJA. Which means that the question going forward is not so much whether TCJA will be extended, but rather which portions will remain in their current form and which may have some 'wiggle room' for change in the next tax bill.

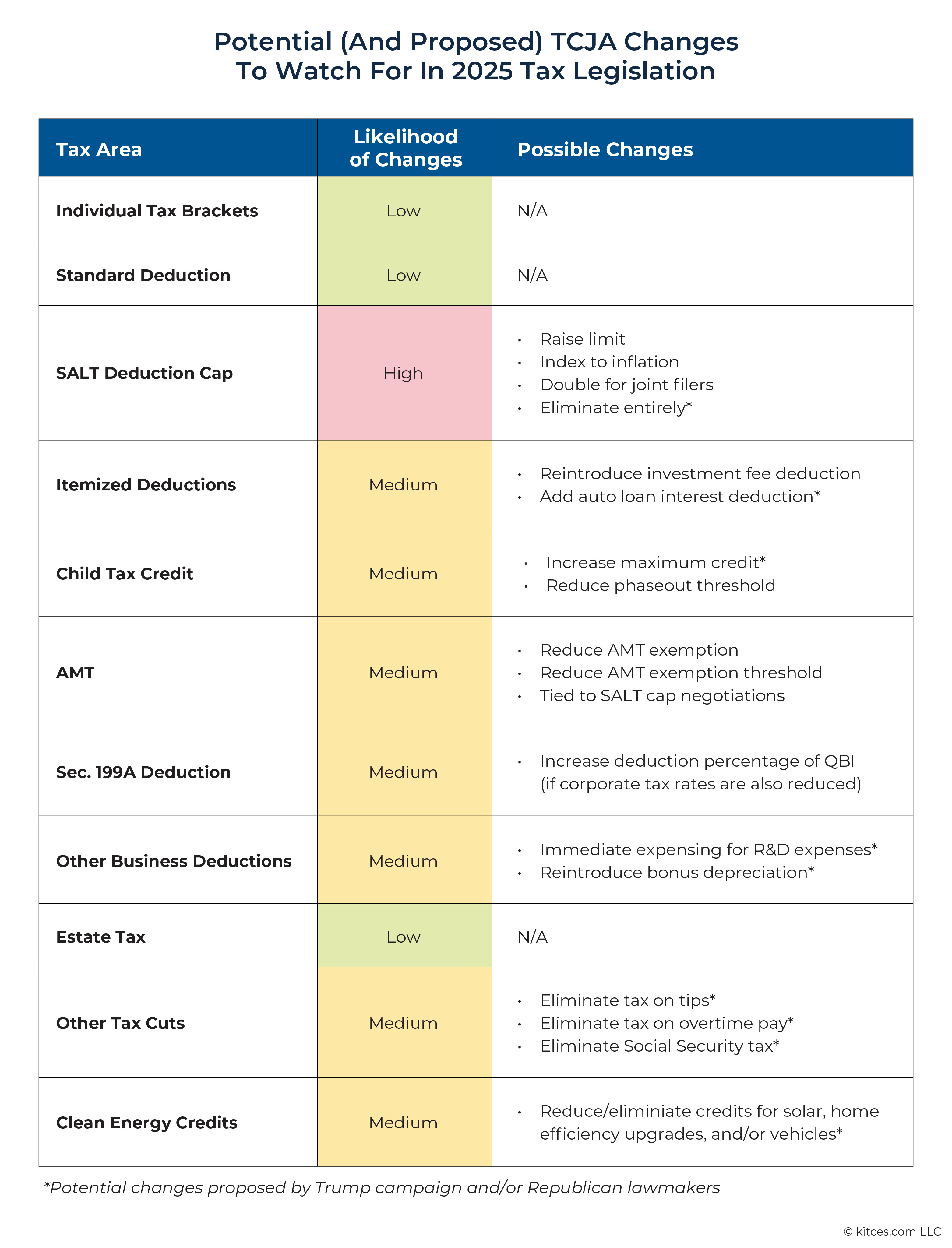

For example, the current 7 tax brackets and increased standard deduction that have been in effect since 2018 are expected to remain largely unchanged. However, the $10,000 limit on State And Local Tax (SALT) deductions, which has been highly contentious with both Democrat and Republican supporters and detractors, is much more likely to become a negotiating point. Some legislators advocate keeping the SALT cap as is, others push for it to be raised in some form, and still others (including the president-elect) want the SALT cap to be eliminated entirely.

Other key areas likely to be impacted include:

- The Child Tax Credit, which is currently capped at $2,000 per child, with some bipartisan support to raise it at least to the pandemic-era $3,600 maximum;

- The Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), which currently affects very few taxpayers, could be amended as part of SALT cap negotiations to kick in at lower income levels for households with high SALT deductions, offsetting the impact of raising or eliminating the SALT deduction cap;

- The Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI) for pass-through owners, which could conceivably be increased if Congress pursues Trump's proposal to cut corporate tax rates from 21% to 15% in order to preserve the proportionate difference between pass-through and corporate tax rates;

- The gift and estate tax exemption, which appears likely to remain at its current elevated level, reducing the urgency for high-net-worth households to gift assets or implement trust strategies to reduce their taxable estate before 2026 (and, in some cases, making it better to avoid gifting assets to preserve the step-up in basis those assets would receive otherwise).

Furthermore, the Trump campaign has proposed a number of additional tax cuts, including tax-free treatment of income from tips, overtime pay, and Social Security benefits, and even eliminating income tax entirely in favor of tariffs. Notably, though, any of these proposals would still need approval from a Congress that may prefer to extend existing tax cuts rather than introduce new ones.

What's certain heading into 2025, however, is that there will be a new tax bill to extend and/or replace TCJA. And while it may not represent as large of a shift from the status quo as TCJA did in 2017, it could still have tax planning implications for millions of Americans – at least until it reaches its own sunset date in another 8–10 years!

When the Republican Party last won unified control over the Federal government in the 2016 elections, one of their most immediate priorities was to enact a tax reform plan. As originally conceived, Republican ambitions for tax reform included lowering tax rates, compressing the existing system of 7 tax brackets down to just 3 brackets, eliminating most deductions, and simplifying the income tax system to the point where most individuals could file their taxes on a piece of paper no bigger than a postcard. Additionally, Republicans aimed to fulfill one of their long-standing policy goals of eliminating the estate tax.

The culmination of those efforts was the 2017 Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA), which was enacted on December 22, 2017. The final law fell short of simplifying the Internal Revenue Code. Instead, it served to make the system more complex by keeping the 7-bracket tax system, retaining most existing deductions, and adding a complicated new deduction in the form of the IRC Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI). So rather than tax reform, TCJA would be more accurately described as a sprawling package of (mostly) tax cuts touching nearly every part of the US tax system, from individual income tax to business tax to estate tax (which Republicans did not manage to eliminate entirely, though they did significantly reduce its reach, as discussed later).

But because the TCJA legislation relied entirely on Republican support to pass through Congress – and because Republicans lacked the 60 votes in the Senate needed to pass the bill over a Democratic filibuster – it needed to be passed through the process known as "reconciliation", which allows budgetary bills to be passed with a simple majority of votes only if they are calculated to be "budget neutral" (i.e., to not increase the Federal deficit) after a 10-year period.

Which meant that in order for TCJA to become law, it needed to come with an expiration date within 10 years of its passage. And so the vast majority of the bill's many provisions were scheduled to 'sunset' on December 31, 2025, at which point (barring any action to extend or further modify the law) the parts of the tax code that TCJA covered would simply revert to the pre-2017 law. This created a situation where the fate of the TCJA's tax cuts would be decided by the 2024 elections, which would determine the party that would control the presidency, Senate, and House of Representatives when TCJA was set to expire.

On November 5, 2024, and in the days that followed, the election results became clear: Just as in 2016, Republicans swept the election, with Donald Trump returning to the Presidency. Republican legislators are also projected to secure narrow majorities in both the Senate and the House of Representatives, placing them in the driver's seat to decide which provisions of TCJA to keep, change, or potentially even expand upon to further achieve their policy aims.

On the surface, it seems that, with Republicans' return to power (including the same president who signed TCJA into law in 2017), the extension of TCJA would be a foregone conclusion. However, while a Republican Congress could simply decide to 'rubber-stamp' the legislation to extend it for another 8–10 years, a complete extension of the existing law is unlikely.

For one thing, the makeup and priorities of the incoming legislature differ from those in 2016. The Paul Ryan-led Republican caucus in 2017 at least initially aimed to accomplish something more like true tax reform and a simplification of the tax code. By contrast, this year's incoming Congress appears more interested in further expanding on TCJA's individual and corporate tax cuts, as well as repealing legislation from the Joe Biden presidency, such as the Inflation Reduction Act.

For another thing, not all sections of TCJA are universally popular, even among Republicans. For example, the $10,000 limit on State And Local Tax (SALT) deductions has opponents among both Democrats and Republicans, particularly among representatives from higher-tax states like New York and California. At the same time, it is still supported by a loose coalition of red-state Republicans (who are happy to see residents of higher-tax, Democrat-leaning states bear more of the cost of balancing the national budget) and Democrats who see an uncapped SALT deduction as an upper-income tax break. As a result, there will likely be negotiations along both partisan and geographical lines over how to address provisions like the SALT cap in any upcoming tax bill.

Finally, while the Trump campaign never released a detailed tax plan ahead of this year's elections, it introduced ideas on the campaign trail for further tax cuts beyond those created by TCJA. These included eliminating taxes on Social Security income, tips, and overtime wages; and even eliminating the income tax entirely and relying solely on tariffs to fund the government going forward. While it remains to be seen which (if any) of these proposals will gain traction in Congress, any of them could theoretically be folded into a new tax bill to replace TCJA.

The only thing that's truly certain now is that there will be a tax bill before the end of 2025 – and if Republicans do indeed achieve a trifecta of the presidency and both sides of Congress, it will be likely to come within the first few months of the year.

The New 'Base Case' Of The TCJA Extension

Ever since TCJA was enacted, there have been 3 basic scenarios for how its sunset would play out: It could be extended essentially in full; it could be amended by extending some sections, altering others, dropping other parts altogether; or it could be allowed to sunset entirely, reverting the tax system to 2017 rules. But as the political tides shifted in the years since 2017 (with the Republican trifecta lasting from 2017–2018, a Democratic trifecta lasting from 2021–2022, and the remaining years featuring some form of divided government), the likelihood of each scenario remained uncertain. However, because the law was written to expire on December 31, 2025, the 'base case' for planning purposes has generally been to assume that TCJA would sunset as scheduled.

With a unified Republican government prevailing in 2025, the base case has shifted. Now, it seems highly likely that any new tax legislation in 2025 will start with what's already in TCJA, with modifications made by the president and incoming lawmakers as they see fit. Which means the question going forward is not whether TCJA as a whole will be allowed to sunset – it almost certainly won't – but rather, which portions of TCJA will likely remain fixed for the future, and which will have more wiggle room for change (and perhaps even further tax cuts).

Individual Income Tax Rates, Exemptions, And The Standard Deduction Are Unlikely To Change

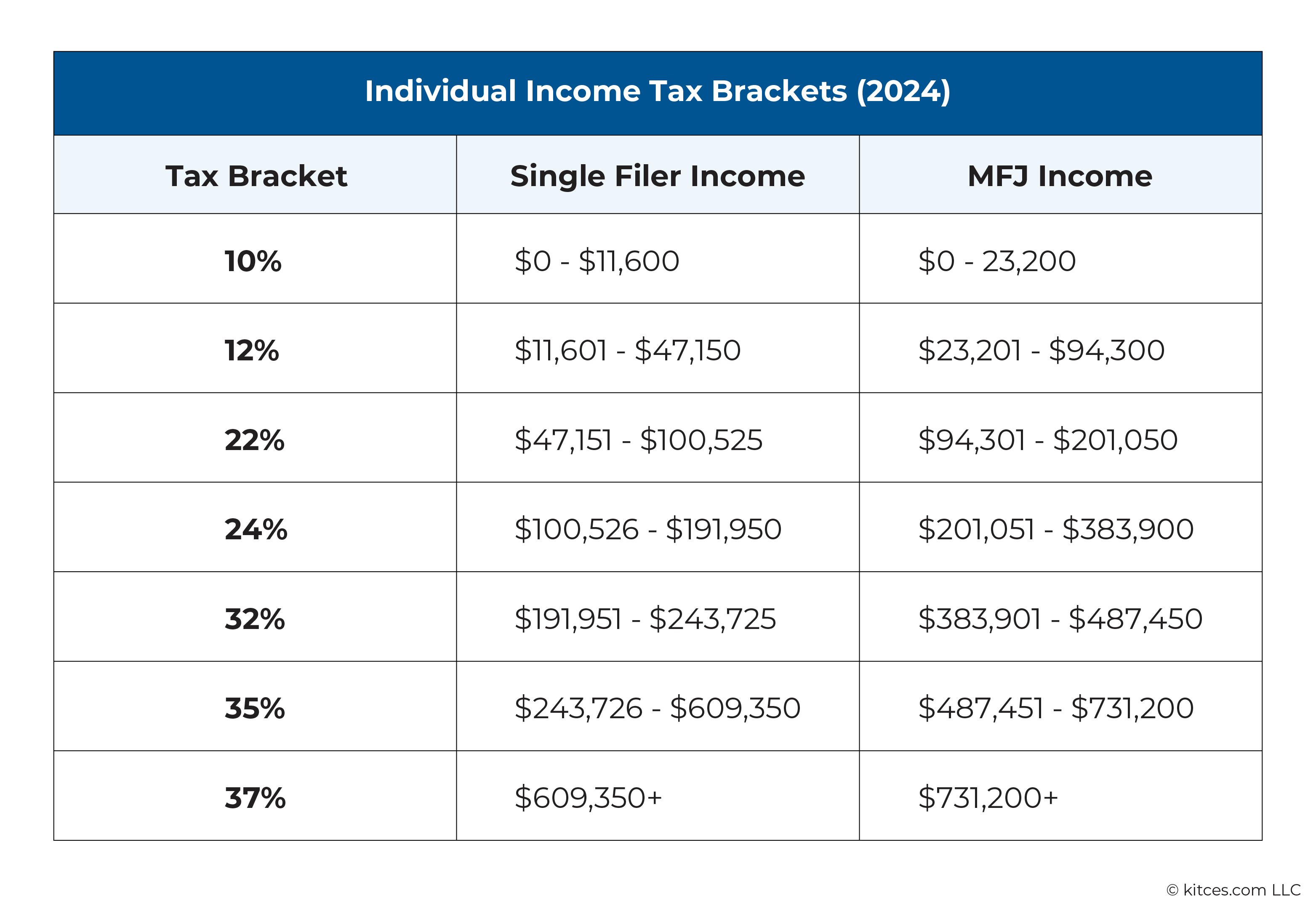

Under TCJA, the 7 individual income tax brackets have stood at 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%, as shown below:

An expiration of TCJA would have raised each of these tax brackets by 1%–4%, as well as shifting around some of the income breakpoints in the higher tax brackets. Under a Republican trifecta, however, it's expected that the current TCJA-era tax bracket structure will remain as is (since, in contrast with 2016, there have been no proposals this year to pare down the tax bracket structure to fewer brackets).

Likewise, the current standard deduction under TCJA ($14,600 for single filers and $29,200 for married filing jointly in 2024) seems likely to remain unchanged under whatever tax plan replaces TCJA instead of decreasing by nearly 50% as would occur if TCJA expired. Additionally, personal exemptions for each household member (along with the Personal Exemption Phaseouts that kicked in at higher income levels), which TCJA eliminated starting in 2018, are unlikely to come back if TCJA is extended.

SALT And Other Itemized Deductions: Room For Change?

In contrast to the tax brackets and standard deduction, which are expected to remain mostly stable, there may be more leeway for changes to itemized deductions (for those taxpayers who are eligible to itemize given the higher standard deduction) as negotiations around the next tax bill take shape.

State And Local Taxes

Of all the provisions in TCJA, perhaps none has been more contentious than the limit on deductions for State And Local Taxes (SALT), which caps the total amount of state and local income tax, real estate tax, and personal property tax that can be deducted on Schedule A to $10,000 per household. Lawmakers from both parties representing higher-tax states have pushed to raise or eliminate the SALT cap, and a provision to raise the limit to $80,000 was even included in the 2021 (Democrat-sponsored) Build Back Better Act, which passed the House but ultimately failed in the Senate.

Notably, on the campaign trail, Donald Trump pledged to eliminate the SALT cap entirely (ironically, given that he signed the law that initially created it); however, other Republicans have shown more resistance to fully repealing the limit.

What seems more likely is that SALT will serve as a negotiating point between lawmakers with varying priorities, with the end result landing somewhere between a continuation of the current $10,000 cap and a full repeal. This could either mean raising the limit to be somewhat higher than where it is today, doubling the cap for married couples (as the $10,000 limit currently applies to both single and married filers), or indexing the limit to inflation (since $10,000 in January 2018, when the cap first took effect, would be worth $12,217 in 2024 dollars). Or some combination of all 3 possible outcomes. But until the new Congress meets and negotiations begin to take shape, the SALT cap will be one of the hardest pieces of the new law to predict given the many interests involved.

Miscellaneous Itemized Deductions (Including Investment Advisory Fees)

Although TCJA left most existing itemized deductions in place (albeit in a limited form in some cases, like the SALT cap), it did eliminate a whole category of "miscellaneous" itemized deductions, which were previously allowable to the extent that they exceeded 2% of the taxpayer's Adjusted Gross Income (AGI).

These deductions included, among other things, unreimbursed expenses for W-2 employees, losses on variable annuities, tax preparation fees, and – most significantly for financial advisors – investment-related expenses, including investment advisory fees. Before TCJA, clients of financial advisors could typically deduct any advisory fees paid from taxable brokerage accounts. After TCJA took effect, however, those fees could only come from after-tax dollars. (Fees from tax-deferred accounts like IRAs, however, can still be paid on a pre-tax basis, provided that they are attributable to the management of the IRA itself.)

However, the advisory industry has lobbied lawmakers to bring back at least the deduction for investment-related fees. For example, CFP Board, FPA, NAPFA, and other industry groups have sent a letter to Congressional representatives, advocating not only for the return of the investment fee deduction, but also for its expansion to make all fees for financial advice (including financial planning fees) tax-deductible. Which makes sense, given that advisory firms increasingly bundle comprehensive financial planning and advice into their AUM fees, while centering their value proposition around the non-investment side of their advice. Which makes it harder to quantify how much of the fee is truly 'investment-related' for the purposes of determining how much would be allowed as a deduction.

Allowing a deduction for all financial planning-related fees would ensure that the full amount of the fee would be deductible, and would also extend the deduction to other, non-AUM advisory fee models, like flat-fee, monthly subscription, or hourly planning fees. Furthermore, it would open up the deduction to clients of 'advice-only' advisors who don't manage investments at all, whose fees have never been deductible since they've never been directly attributable to investments.

It remains to be seen whether efforts from the advisory industry will persuade lawmakers to reintroduce (let alone expand) the deduction for investment-related expenses, but it will be worth watching as negotiations pick up speed around the tax bill in the coming year.

Auto Loan Interest

Another of Trump's promises on the campaign trail was to make the interest on auto loans tax-deductible, likely as another itemized deduction similar to mortgage interest on a primary residence. This change would certainly provide relief to some auto loan borrowers, with both car prices and interest rates having increased in recent years (where the average payment on a new car has gone up to $735/month). Being able to deduct a portion of that payment could help ease the financial strain on households that rely on a vehicle for transportation.

However, it remains to be seen how seriously to take this proposal, as lawmakers may not want to prioritize adding a 'new' deduction (at least one that hasn't been available since the Reagan-era Tax Reform Act of 1986 eliminated the deduction on non-mortgage personal loan interest) over other options, like raising or eliminating the SALT cap or restoring miscellaneous itemized deductions. In other words, it's probably not worth financing a new Tesla today on the assumption that the interest will be tax-deductible next year.

Child Tax Credit: Keep Or Expand?

The Child Tax Credit has become an increasingly substantial tax break for families with young children in recent years. Initially set at $500 per qualifying child (age 0–16) when introduced in 1998, the credit increased to $1,000 in 2001 and remained at that level until 2017. When TCJA was passed, however, it doubled the maximum child tax credit to $2,000 per qualifying child and raised the credit's phaseout threshold from $75,000 (for single filers) and $110,000 (for married couples filing jointly) to $200,000 and $400,000, respectively. TCJA also reduced the minimum income needed to claim the credit to $2,500 and made up to $1,400 of the credit refundable, greatly expanding the Child Tax Credit's reach and value to families, particularly those with multiple kids.

However, for many families, TCJA's increased Child Tax Credit didn't actually result in lower net taxes – it simply served to offset the tax increase caused by the elimination of personal exemptions for each taxpayer and dependent.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the American Rescue Plan further increased the Child Tax Credit to a fully refundable maximum of $3,600 per qualifying child aged 0–5 and $3,000 per child aged 6–17 for 2021. Despite efforts by the Biden administration and Democratic lawmakers to extend these higher amounts through 2025 as part of the Build Back Better Act of 2021, the bill ultimately failed to pass the Senate, and the maximum credit reverted to $2,000 in 2022 – where it remains today.

During the lead-up to the 2024 elections, both presidential campaigns floated the idea to expand the Child Tax Credit beyond its current levels. The Harris campaign proposed restoring the COVID-era credits of $3,000 and $3,600, with parents of newborns qualifying for a credit of up to $6,000. Meanwhile, Trump's vice-presidential candidate, JD Vance, said in an interview that he "would like to see" a credit of $5,000 per child. However, the Trump campaign never mentioned the proposal again outside of that one interview, suggesting that the more-than-doubling of the Child Tax Credit may not be a priority for the next Trump administration.

Still, an extended TCJA would likely at least retain the existing $2,000 Child Tax Credit, particularly since personal exemptions are unlikely to be reinstated. But with strong bipartisan interest in raising the Child Tax Credit in recent years – including the proposals floated by both presidential campaigns this year – there may still be pressure to increase the Child Tax Credit, even if only modestly, such as by indexing the maximum credit amount to inflation (although any increases could also come with some caveats that reduce their impact on the budget, such as lowering the income thresholds where the credit phases out).

Alternative Minimum Tax: Connected To SALT Cap Negotiations?

One area of TCJA that got relatively little attention was its changes to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). Prior to 2018, families with low- to mid-6-figure incomes – approximately $100,000–$400,000 for single filers and $200,000–$500,000 for joint filers – routinely owed AMT on top of their regular tax, especially if they had high state income and/or property taxes and multiple dependents. This was because the SALT deduction and personal exemptions are both added back to household income for AMT purposes, increasing the likelihood of triggering AMT.

However, TJCA's limitation of the SALT deduction and elimination of personal exemptions made those 2 common add-backs much less impactful for creating AMT exposure. Furthermore, TCJA also increased the AMT exemption (deducted from AMT income before calculating AMT) and greatly raised the threshold at which this exemption begins to phase out. As a result, outside of relatively uncommon cases – like large Incentive Stock Option (ISO) exercises that significantly add to income for AMT purposes – AMT rarely affects most taxpayers today, with only about 200,000 total households subject to AMT under TCJA (compared to over 5 million households under the pre-TCJA rules).

With TCJA likely to be extended, it seems that AMT will remain an issue for only a relatively small number of households going forward. However, there could be a reason for lawmakers to consider making changes to AMT as they formulate the next tax bill, which revolves around the SALT deduction cap.

Under the pre-TCJA system, taxpayers technically had the unlimited ability to deduct state and local taxes. Except there was a catch-22, which was that once a household reached a certain income level – and by extension had a significant amount of state and local taxes to deduct – they were almost inevitably pushed into AMT, which notably does not allow a deduction for state and local taxes. And so many upper-middle-income households really didn't get a full SALT deduction because it was at least partially (or even entirely) offset by a corresponding increase in AMT.

This dynamic meant that, despite the attention given to the $10,000 SALT deduction limit imposed by TCJA and its effects on residents of higher-tax states, the reality was that many of those states' residents had never been able to fully deduct their state and local taxes in the first place due to AMT.

Nerd Note:

Many people who owed AMT due to high state and local taxes never actually realized they weren't receiving the full value of their SALT deduction because of how AMT is reported on tax returns. When a taxpayer owes AMT, only the amount exceeding their 'regular' tax calculation is reported on their return. Meaning that for these taxpayers, the full SALT deduction still shows up as an itemized deduction on Schedule A – it's just offset by the higher amount of AMT listed much further down on the return.

And because many taxpayers don't fully understand how AMT is calculated, they might not realize the direct connection between the amount of state and local taxes they deduct and the amount of AMT they owe. This lack of awareness partially explains why so many people were upset about the SALT deduction limit imposed by the TCJA when, in reality, they were never getting the full SALT deduction to begin with!

So, as the SALT cap negotiations get underway during the 2025 legislative session, one factor we might hear about is whether AMT should be adjusted accordingly so that, if the SALT cap is indeed raised or eliminated, it could again create more AMT exposure for higher-income households (which would go towards reducing the approximate $1.2 trillion cost of eliminating the SALT cap). This could mean either reducing the AMT exemption to pre-TCJA levels, setting lower income thresholds for the AMT exemption phaseout, or some combination of both. Either way, this would effectively reinstate a 'stealth' limit on the SALT deduction – at least for households in the income ranges where AMT applies. Notably, AMT becomes less of a factor for households earning above $600,000 or so, which means that the households that stand to gain the most from an unlimited SALT deduction are those at the very highest income levels.

IRC Section 199A And Other Business Deductions

TCJA introduced a new and immensely consequential deduction under for owners of pass-through businesses, like LLCs, partnerships, and S-corporations, in the form of the Section 199A deduction. At a high level, the new law allows these business owners to deduct up to 20% of their Qualified Business Income (QBI), which, in addition to traditional business income, can also include income from many rental properties and even REIT funds. Above a certain income level, however, the deduction phases out for owners of a specific category of businesses known as "Specified Service Trades or Businesses" (SSTBs). This category includes lawyers, accountants, consultants, and yes, financial advisors (along with other businesses whose main assets are the skill or reputation of their employees).

With a Republican trifecta in Congress and the White House, it's almost certain that the Section 199A deduction will continue beyond its original 2025 sunset date. However, it's very possible that lawmakers could consider modifying or even increasing the deduction in the next tax bill.

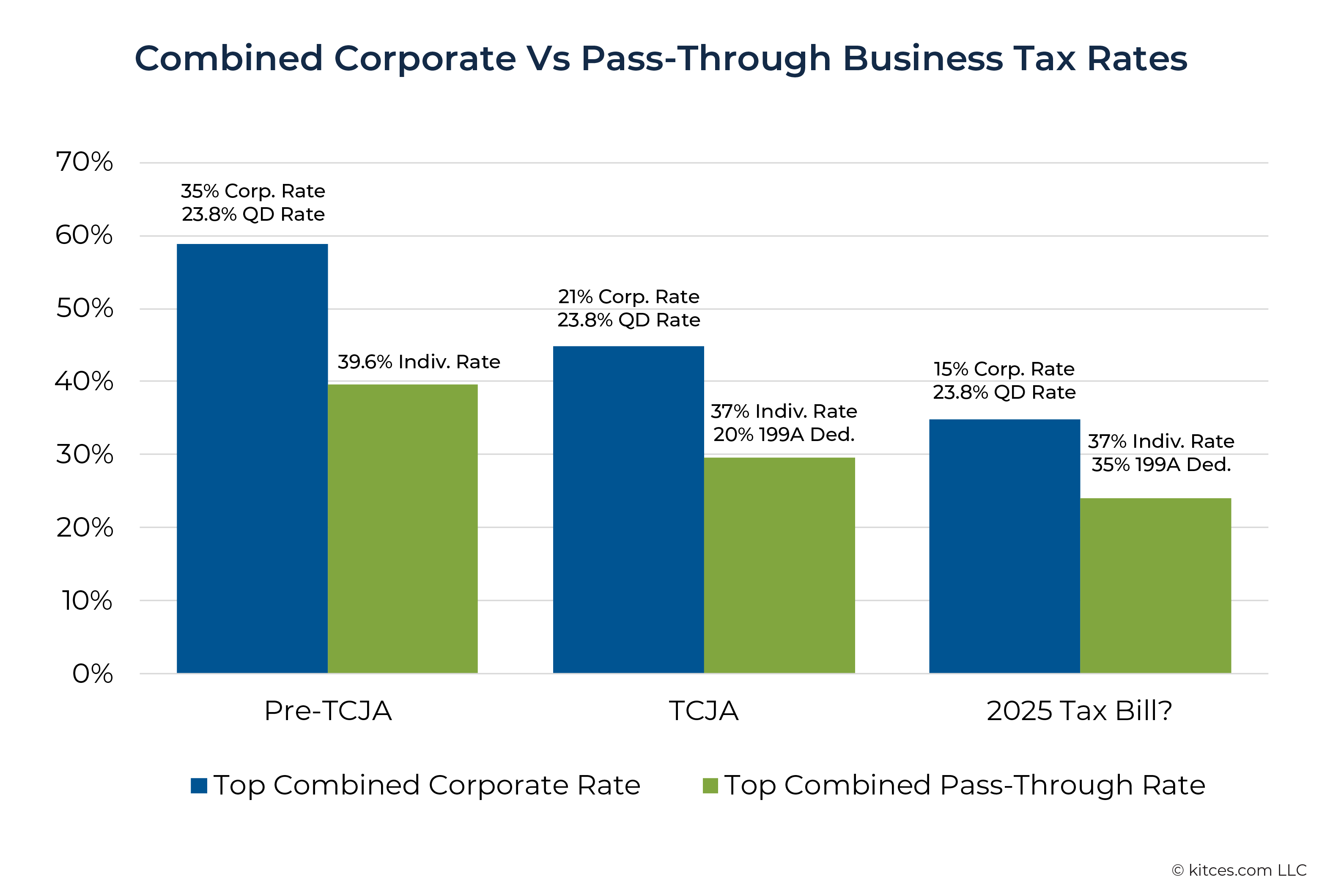

The purpose of the Sec. 199A deduction was to reduce the effective tax rates of pass-through business owners by an amount roughly parallel to those of C-corporations, for which TCJA cut the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. Specifically, since TCJA cut the top combined tax rate paid by corporate shareholders (i.e., the top corporate tax rate plus the top rate on qualified dividend payments) from 35% + 23.8% = 58.8% to 21% + 23.8% = 44.8% – a roughly 24% relative reduction – the law also gave pass-through business owners a 20% deduction against their own business income to preserve the relative difference between the corporate and pass-through tax rates.

Notably, in his 2024 campaign, Trump has pushed for the idea of reducing corporate tax rates even further, from 21% to 15%. Which would mean the top combined corporate tax rate would be reduced from 21% + 23.8% = 44.8% to 15% + 23.8% = 38.8%, representing a 34% reduction from the 'original' combined rate of 58.8%. If the next Congress goes through with this proposal, then, they may also consider increasing the Section 199A deduction – perhaps even up to 30%–35% of QBI – which would roughly maintain the proportional difference between corporate and pass-through rates, as shown below.

Additionally, there may be further debate around which types of businesses qualify as Specialized Service Trade or Businesses (SSTBs) for which the Section 199A deduction phases out above certain income thresholds. In the original TCJA legislation, architects and engineers secured a carve-out in the law that specifically excluded their professions from the SSTB definition. As negotiations for the next tax law take shape, other professions will likely hone their lobbying efforts to receive similar carve-outs for their members as well.

Trump has also pledged to restore the immediate expensing for R&D costs, which TCJA mandated to be amortized over 5 years (in another instance of his calling to reverse a provision included in his own previous administration's tax bill). Additionally, he has called for restoring bonus depreciation, which, under TCJA, initially allowed for a 100% immediate deduction of qualified business property, but is now set to phase down gradually: down to 80% in 2023, 60% in 2024, 40% in 2025, and 20% in 2026, with complete elimination thereafter. Both plans would create more incentives for businesses to invest in R&D and equipment by allowing them to deduct the entire cost upfront.

Estate Tax: Pumping The Brakes On Gifting Strategies

TCJA had a profound effect on estate tax planning for high-net-worth families, as it doubled the gift and estate tax and Generation-Skipping Tax (GST) exemptions from $5.6 million per person to $11.2 million. By 2024, these exemptions have increased to $13.61 million per person, meaning a couple with $27.22 million of net worth could pass away this year and owe zero estate tax. However, the expiration of TCJA in 2026 would reduce the exemption to approximately $7 million per person, potentially reexposing households with net worths between $14 million and $28 million to estate tax, and increasing estate tax exposure for those already above that threshold.

In 2019, the IRS issued regulations confirming that taxable gifts made in 2018 through 2025 would, in fact, be subject to the higher gift and estate tax exclusions in effect at the time the gifts were made. Meaning that, for instance, a couple worth $30 million could give away at least $27 million in 2024 – either directly to an individual or to an irrevocable trust that removes the assets from their estate – and owe no estate or gift tax on that amount, even if their combined estate exemption reduces to only $14 million by the time of their deaths.

As a result, in the last few years, wealthy families have rushed to establish estate planning structures that allow them to gift assets out of their estates and take advantage of the 'temporary' higher limits on tax-free gifting before TCJA's expiration. Even though there has always been the possibility that the higher estate exemptions would be extended, for many high-net-worth families, the potential for millions of dollars in estate tax savings in the event TCJA did sunset was worth the 'risk' of making pre-death transfers to heirs or trusts, even if the higher exemptions stayed in effect.

With a Republican trifecta, it seems likely that the estate tax exemption will remain at its higher TCJA level for now. Which means that for those scrambling to gift assets or transfer them into trusts, there's less urgency to do so before the end of 2025. For many estates, in fact, it may be better to avoid gifting assets that wouldn't be subject to estate tax, as doing so would forgo the step-up in basis they would receive if held until death.

However, while there's no longer an immediate need to gift assets before TCJA sunsets, there are still reasons to put estate planning strategies in place. For example, some families who are already subject to estate tax might benefit from putting assets with high potential for future appreciation (e.g., shares in a fast-growing business) into trusts to help keep that future growth out of the estate. And for residents of states with their own state-level estate taxes, it can make sense to gift or transfer assets solely for the state estate tax savings, even if there's no Federal estate tax exposure.

And regardless of wealth levels, trust strategies can provide valuable ways to distribute assets according to the donor's wishes, protect assets from creditors or divorce, or allow people with disabilities to receive public benefits without exceeding income or asset limits. All of which are worth considering even when there are no estate tax considerations at play.

Other Tax Proposals To Watch

Although Trump's campaign never released a formal tax plan, he made a number of pledges to watch for inclusion in a future tax bill. Most prominently, Trump has called for tax-free treatment of 3 types of income: tips, overtime wages, and Social Security benefits. However, none of these proposals would be easy to implement, from either a practical or a budgetary standpoint, as they could create incentives that reshape how service and hourly workers, as well as Social Security recipients, are paid in the future.

For example, making tips tax-free would naturally incentivize service workers to earn a higher proportion of their income from tips. While this would be good for their employers (who would have to pay less in wages to those workers), it would also make workers more reliant on a less stable source of income, as tips are made entirely at the customer's discretion. Additionally, tax-free tips could make tipping much more prevalent in everyday transactions, even in scenarios where it isn't commonly seen today. And with customers already growing frustrated with "tipflation" in recent years, such an increase could ironically cause a consumer backlash where customers end up tipping less, resulting in a worse overall outcome for workers relying on tips.

As for the proposal to make Social Security tax-free: While the tax on Social Security income has always been broadly unpopular, and any move to eliminate it would undoubtedly be well-received by current Social Security recipients, the estimated $1.5 trillion that the tax cut would cost over the next 10 years might be more than lawmakers in Congress are willing to accept. Additionally, cutting taxes on Social Security income could have long-term implications for the state of the Social Security system itself since the taxation of current benefits is a core part of funding future Social Security benefits. Eliminating the tax on Social Security could lead to a quicker depletion of the Social Security trust fund, potentially resulting in a quicker and sharper reduction in benefits for future recipients, whose ongoing payments would be funded entirely by payroll taxes paid by workers.

Finally, in order to pay for the costs of extending or expanding TCJA, some Republicans have raised the idea of repealing parts (though perhaps not all) of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which, among other things, created or expanded tax credits for solar panels, home energy efficiency upgrades, and electric vehicles. Meaning that individuals looking to take advantage of these credits by making home upgrades or buying an electric car may want to do so sooner rather than later, since they could be among the first targets for repeal.

Political Realities Of A TCJA Extension

Altogether, even though the 2025 tax bill isn't expected to impose sweeping changes on the sale of the original TCJA (since TCJA itself represents the baseline on which much of the bill will be constructed), it does have the potential for some significant changes that cut across numerous areas of the tax system, as summarized below.

When assessing all of the proposals and areas where TCJA may be extended or amended, however, a key consideration is that while Republicans are expected to have majorities in both the House and Senate in 2025, these majorities are projected to be extremely narrow. Which means that any tax bill replacing TCJA will need support from nearly every Republican legislator in both chambers, with very little room for 'defection' on either side.

So while it may appear as though Republicans will be able to pass any bill that they want with their trifecta, the reality is that the bill's passage depends on the support of lawmakers with many differing priorities and philosophies – from those committed to cutting taxes further no matter the cost to those reluctant to pass any bill that would continue to add to the Federal deficit. As the Democrats learned with the Build Back Better Act of 2021, which stalled after losing the vote of a single Democratic senator, it isn't easy to create a wide-ranging piece of legislation that satisfies everyone, even within a single political party.

Therefore, it's unlikely that all of the proposed tax cuts discussed above will make it into the final law, or at least not without some offsetting tax increases in other areas. The question going forward is which proposals – on both the tax cut and the tax increase sides – will gather enough support to find their way into next year's tax bill. What seems certain, though, is that the 2016-era 'dream' of tax reform to simplify the calculation and filing of taxes is still a very long way off, since any tax cuts and offsetting tax increases that make it into the new law are all but guaranteed to make the system even more complicated!

Additionally, because the TCJA extension and replacement bill may pass with only Republican votes, it will in all likelihood have to go through the reconciliation process once again to allow passage by a simple majority, just as in 2017. Which means that, no matter how the new law takes shape, we get to look forward to another sunset deadline that's likely to be determined by the 2032 elections. So, just as we wrap up a 7-year stretch of speculation and planning for TJCA's sunset, taxpayers – and planners who advise them – could very well be getting ready to face another 7–8-year cycle of planning for whatever law comes next!

Leave a Reply