Executive Summary

For most people, Social Security benefits are calculated using a single formula, which takes into account the individual's history of earning income on which they paid Social Security tax. But historically, a subset of workers that spent at least part of their careers in positions that did not pay Social Security tax – including many state and local government workers like teachers and police officers – have had their Social Security benefits reduced, sometimes down to $0. This reduction stems from two provisions known as the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) and Government Pension Offset (GPO), which were designed to address how benefits are calculated for these workers.

At a high level, the WEP and GPO reduce the Social Security benefits of retirees who receive pension payments from a non-Social-Security-covered employer. These reductions apply to retirees eligible for Social Security benefits either under their own name (in the case of the WEP) or under their spouse's name (in the case of the GPO). In both cases, the provisions were intended to address perceived fairness issues in the Social Security calculation for those who had worked in non-covered jobs since the income from those jobs is excluded when calculating Social Security benefits. This exclusion often makes these workers appear to have lower average incomes, which would entitle them to disproportionately higher benefits. The WEP and GPO adjustments were meant to 'correct' the discrepancy.

However, the WEP and GPO proved unpopular and difficult to manage in practice. The penalty calculations were complex and difficult to estimate, and the provisions were poorly communicated to those affected. For instance, annual Social Security statements showed 'full' benefit amounts without accounting for the WEP or GPO adjustments, leaving many individuals unaware of their reduced benefits until they received their first (reduced) Social Security check. This lack of clarity made retirement planning significantly more challenging.

In response, Congress passed the Social Security Fairness Act at the end of 2024, repealing the WEP and GPO in full. This means individuals whose Social Security benefits were reduced by either provision can expect to have their full benefits restored. And because the Act is retroactive to January of 2024, these individuals can also expect to receive payments to cover benefit reductions going back to that date as well!

For advisors, the main planning takeaway is that clients previously affected by the WEP or GPO can expect to receive more Social Security income going forward – in some cases significantly more – presenting opportunities that may positively affect their retirement planning. As a result, it's important for advisors to first identify which clients are currently subject to WEP or GPO and ensure that those who may need to file for benefits do so as soon as possible. For example, clients whose spousal benefits were reduced to $0 by the GPO may have never filed for benefits, making it key to file now that the GPO has been eliminated.

The key point is that while the WEP and GPO only affected a certain subset of retirees and spouses, these provisions made planning more complex for those impacted. Now that the WEP and GPO have been repealed, retirement planning will be significantly easier going forward. With the caveat that, with the sustainability of Social Security already in question, there could be more changes in the coming years that might offset the effects of the Social Security Fairness Act in unpredictable ways. Which makes it all the more important for advisors to help their clients build plans with the flexibility and resiliency to withstand all the changes yet to come!

Ever since the Social Security program was created by the Social Security Act of 1935, the distribution of Social Security benefits to retirees, disabled workers, and their spouses and children has been based on a simple premise: If a worker pays Social Security taxes on their income, they (and their spouse and any eligible children) will be entitled to benefits based on their income history and how much they paid into the system.

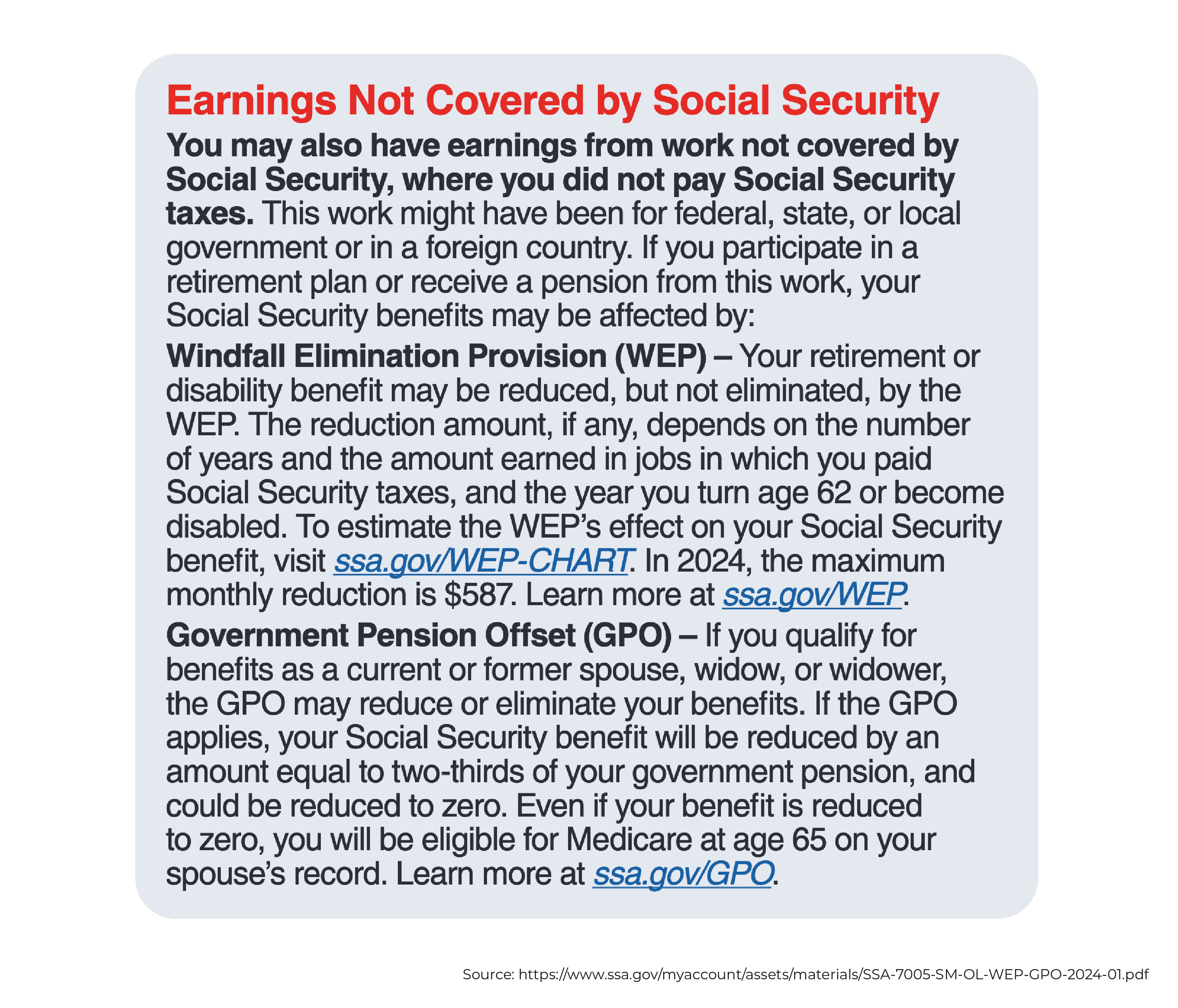

But beginning in 1977, this defining premise of Social Security has had an asterisk for certain people – specifically, those who spent at least part of their careers in jobs where they didn't pay Social Security tax, for which they now receive payments from a pension plan. This most often includes certain state and local employees like teachers, police officers, and firefighters; but also those who worked in a foreign country where they didn't contribute to the U.S. Social Security system.

When these workers are also eligible for Social Security benefits, either under their own name or as a spouse or survivor of another worker, their benefits have often been reduced, and even outright eliminated, by one of two provisions: the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP), which reduces benefits for workers based on their own earnings, and the Government Pension Offset (GPO), which reduces spousal and survivor benefits.

On January 5, 2025, however, President Biden signed the Social Security Fairness Act into law, which fully repeals both the WEP and the GPO. The result of the Act will be to potentially increase Social Security benefits by hundreds or even thousands of dollars per month for millions of retirees who receive pension payments from state, local, and/or foreign governments.

For financial advisors, this repeal represents a big planning opportunity. Clients whose Social Security benefits have been reduced by the WEP and GPO can now expect to receive an increased amount of guaranteed Social Security income during retirement. But understanding who will be affected – and how much of an impact the Act will have on retirement income planning – requires a high-level overview of how the WEP and GPO have worked up until now.

Social Security 'Fairness' And The Effects Of Non-Covered Earnings On Benefits

When calculating the Social Security benefits that an individual would be entitled to, the Social Security Administration (SSA) looks at the year-by-year history of all the earnings on which they paid Social Security tax. These earnings are indexed to inflation for all years before the worker turns 60. The SSA then identifies the 35 highest-earning years in the worker's career, calculates the average inflation-indexed earnings for those years, and divides the result by 12 to reach the individual's Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME). This figure serves as the base number from which an individual's benefits are calculated.

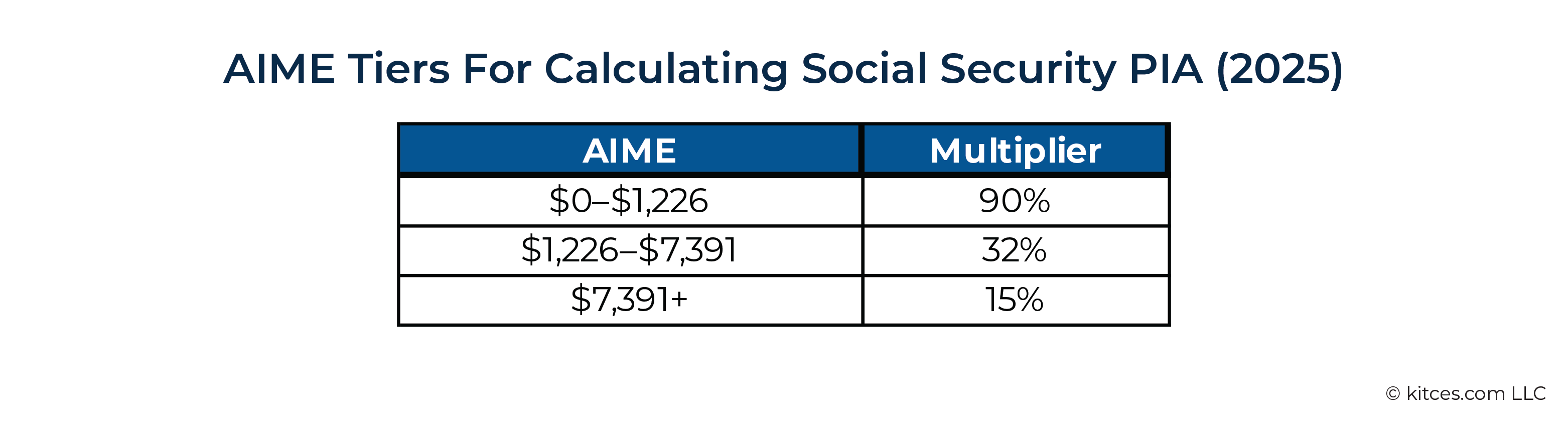

The actual benefit that an individual is entitled to at their full retirement age – the Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) – is calculated using a tiered structure along the same lines as the Federal income tax bracket system. The individual's AIME is segmented into up to 3 different portions, each of which is multiplied by a different percentage, with the results being added together to end up with the individual's PIA.

For 2025, the first $1,226 in AIME is multiplied by 90%; the next $6,165 (up to $7,391 in AIME) is multiplied by 32%; and anything beyond that is multiplied by 15%. These “bend points” between tiers are adjusted for inflation each year; when calculating an individual's PIA, the bend points used are those for the year in which the individual turned 62 (or the year when they became disabled or died prior to age 62).

The point of the tiered calculation is to create a progressive benefits structure: Just as households with low taxable incomes pay a lower overall rate on Federal income tax than those with higher incomes, individuals with relatively low earnings over their careers – and therefore relatively low AIME – receive higher Social Security benefits in proportion to their AIME.

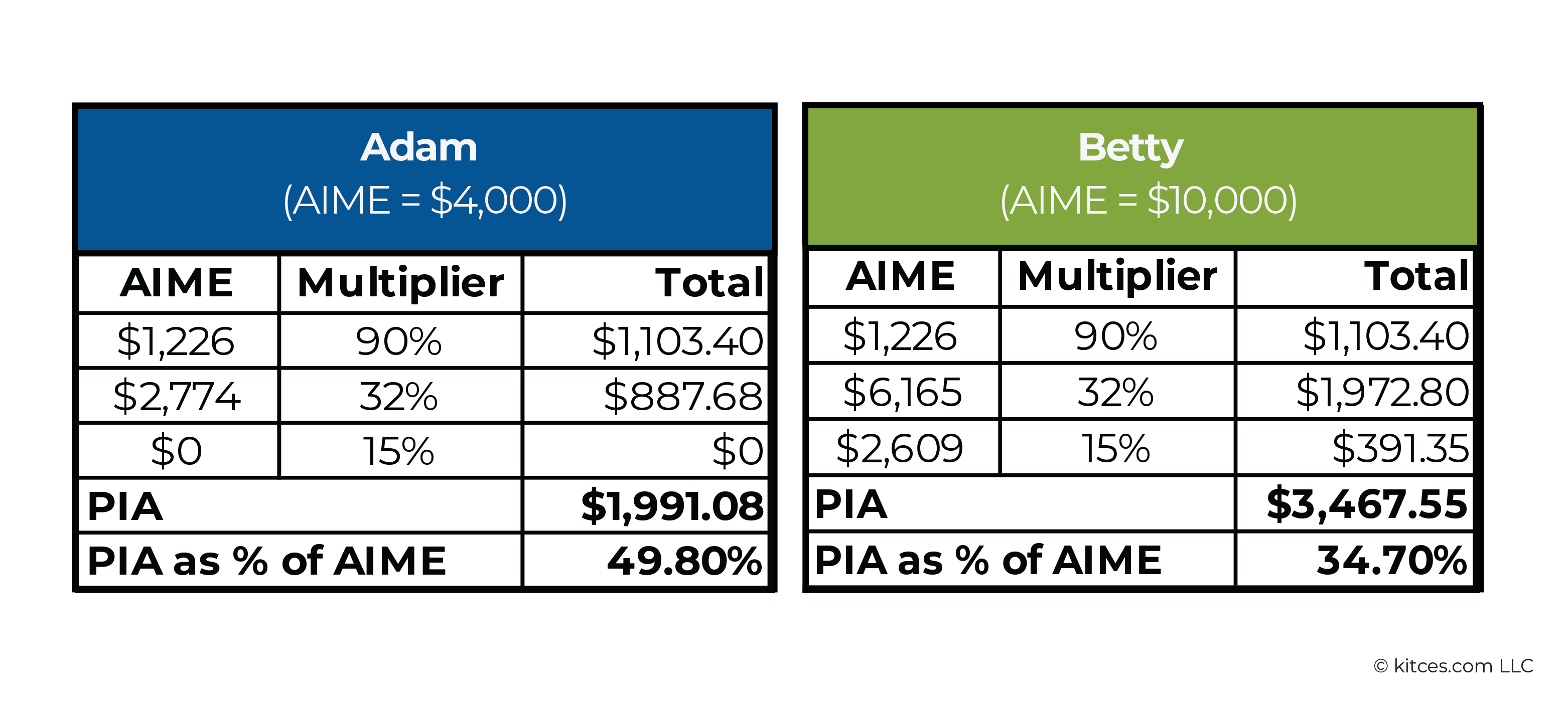

Example 1: Adam and Betty are twins who started and finished their careers at the same time. Adam spent his career as an artist, and when he retired, his AIME was $4,000. Betty, meanwhile, became a corporate executive, and when she retired, her AIME was $10,000.

Assuming they both turned 62 in 2025, the two siblings' Social Security PIAs would be calculated as follows:

As shown above, while Betty's PIA monthly benefit of $3,467.55 is higher than Adam's $1991.08 due to her higher career earnings, Adam's PIA represents a larger proportion of his average lifetime earnings (49.8%) compared to Betty's (34.7%).

In summary, the more years an individual spends earning low (or zero) income, the higher the percentage of their average income that will be 'replaced' by their monthly Social Security benefits – provided they meet the cumulative 40 quarters of qualifying income required to be eligible for Social Security benefits to begin with.

Social Security Implications For Non-Social Security-Covered Government Workers

After the Social Security Act was passed in 1935, not all workers were subject to Social Security tax. Instead, most Federal, state, and local government employees paid into their governments' public employee pension systems rather than Social Security. Beginning in the 1950s, many state and local governments elected to have their employees covered by Social Security under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 418. Later, Congress made Social Security coverage mandatory for Federal government employees hired after 1983. However, as of 2018, approximately 6.6 million state and local government employees remained uncovered by Social Security. These workers don't pay Social Security tax on their earnings, and their income is also excluded from their earnings history used to calculate their AIME and PIA.

While it seems reasonable that a state or local government worker who spends their career paying into their public employer's pension system rather than Social Security should not receive Social Security benefits based on their own earnings, some issues of fairness arise when it comes to workers who are eligible for both a (non-covered) state or local pension and Social Security benefits.

The WEP Penalty On Social Security Benefits For Non-Covered Pension Recipients

The first fairness issue arises when an individual works for part of their career in a public-sector job that is not covered by Social Security, but at some point also works in another job that is covered by Social Security for long enough to be eligible for Social Security benefits (at least 40 quarters). When the Social Security Administration (SSA) calculates their benefits, it disregards any income that they earned at their non-covered job, which means that every year they worked solely in the non-covered job is treated as if they had earned $0 for purposes of calculating their Social Security benefit.

This exclusion has the effect of making that individual seem like they had a lower income (since every year of low or zero Social Security-covered earnings effectively drags down the worker's AIME) when they may not have actually had a very low income. Due to the progressive nature of the PIA calculation, as described earlier, this lower AIME results in Social Security benefits that represent a higher percentage of their AIME than if all their career earnings were covered by Social Security. In practice, this results in the worker's combined retirement benefits – from both their public employer pension and Social Security – adding up to something greater than what their Social Security benefits alone would have been if they had worked their whole career solely in a Social Security-covered job.

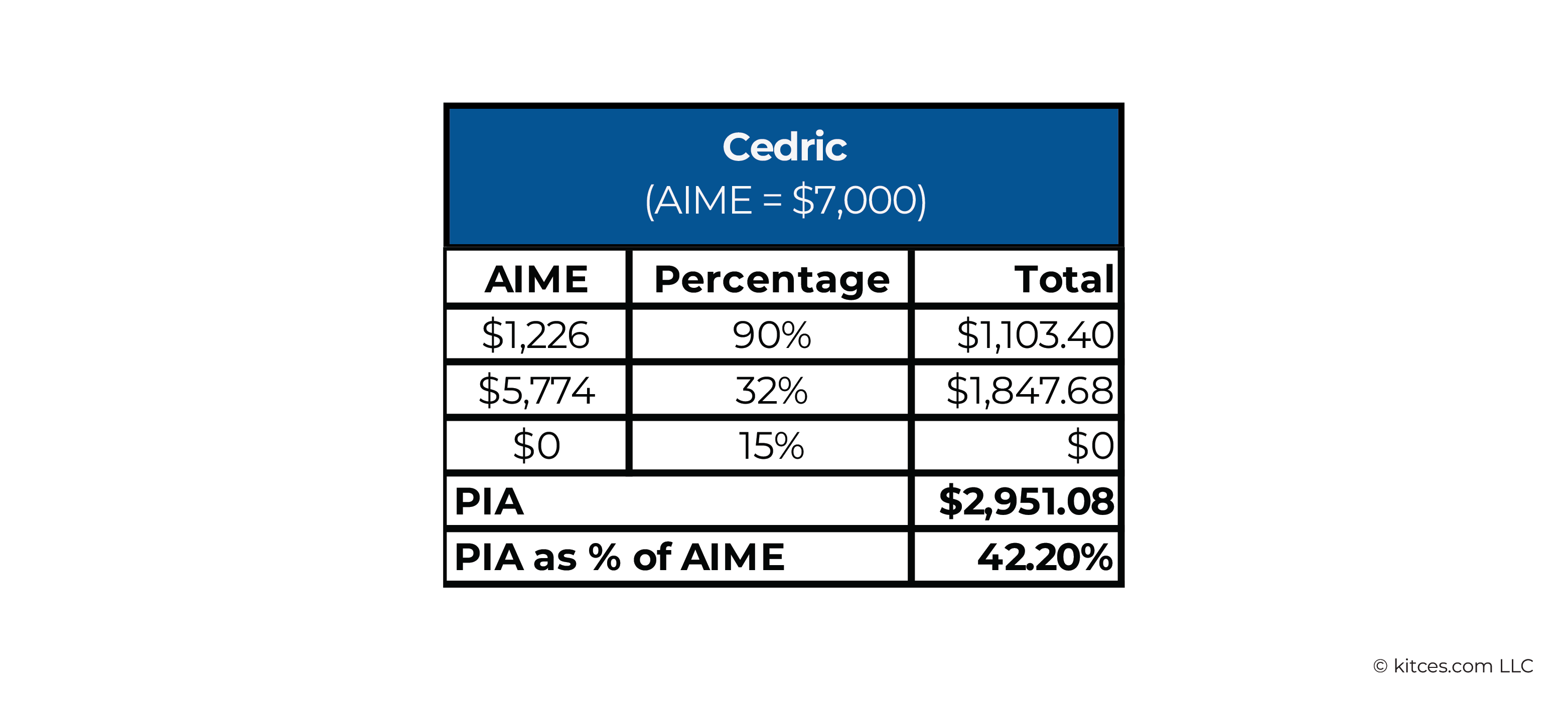

Example 2: Cedric and Deirdre both worked for exactly 35 years and earned an inflation-adjusted average of $7,000 per month.

Cedric worked his entire career in the private sector, paying Social Security taxes on all of his earnings. At the end of his career, his AIME is $7,000, resulting in a PIA of $2,951.08 as calculated below:

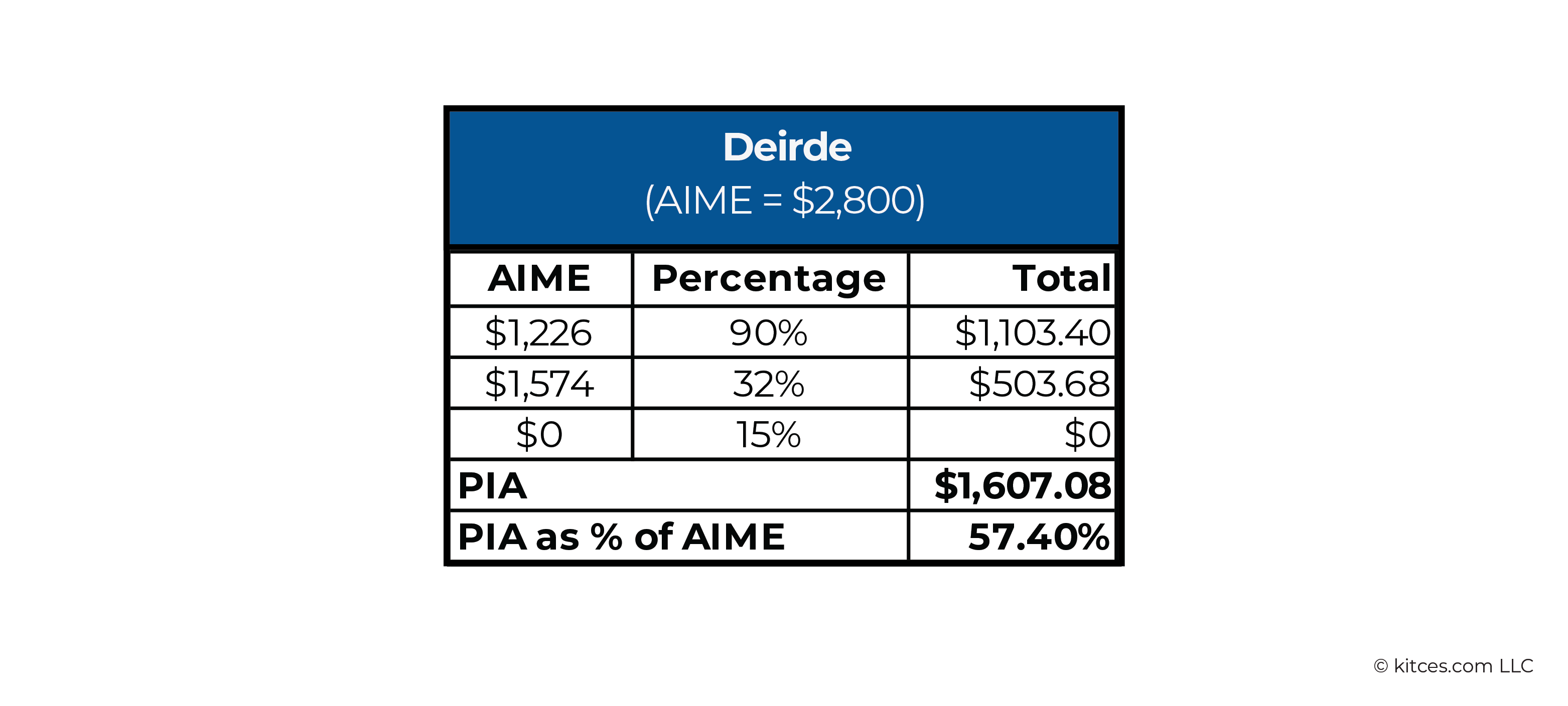

Deirdre, on the other hand, worked for 21 years as a non-Social Security-covered teacher before moving to an administrative role where she became covered by Social Security. Assuming her inflation-adjusted income was the same in both her covered and non-covered positions, her lifetime earnings for Social Security purposes consist of 21 years of $0 (i.e., the years she spent as a non-covered employee) and 14 years of $84,000 per year (the years she spent as a covered employee), for an AIME of ($84,000 × (14 ÷ 35)) ÷ 12 = $2,800. Which results in a PIA of $1,607.08:

Even though Cedric and Deirdre earned the exact same amounts over their respective careers, their Social Security benefits tell a different story. Deirdre's Social Security benefits represent 57.4% of her average Social Security-covered earnings, while Cedric's only represent 42.2% of his. This discrepancy arises because Deirdre's 21 years of non-covered employment are treated as $0 earnings for Social Security purposes, lowering her AIME and amplifying the impact of the PIA's progressive formula.

As a result, if Deirdre's state pension is more than $1,344 per month, her combined monthly pension and Social Security income will total more than Cedric's Social Security benefits of $2,951 – despite their identical lifetime earnings.

To address this issue, Congress created the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) in 1983, which applies to workers who meet all three of the following criteria:

- They worked at a job where they didn't pay Social Security taxes;

- They qualified for a pension from that job; and

- They worked at one or more other jobs where they did pay Social Security taxes, which qualified them for Social Security benefits.

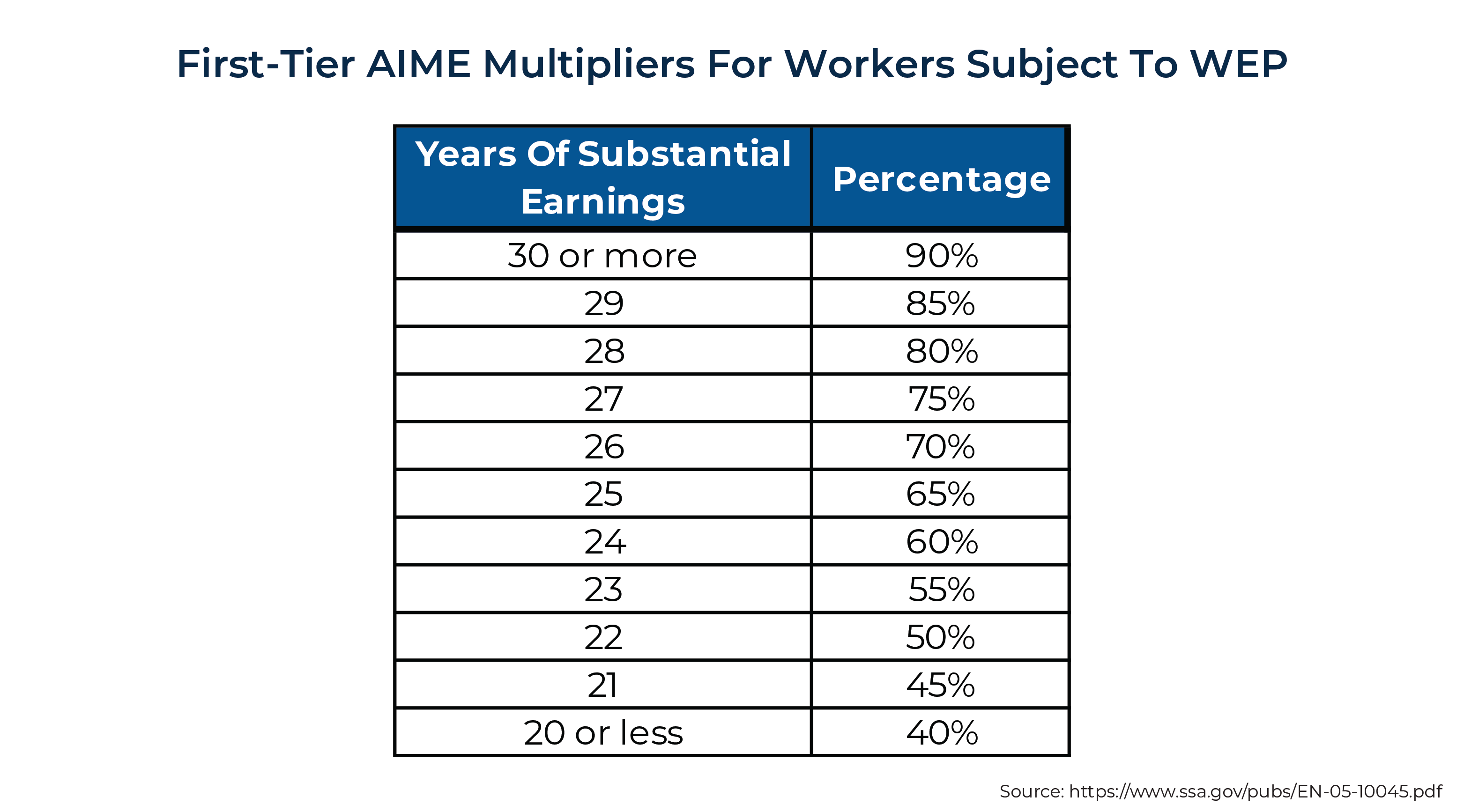

In a nutshell, the WEP adjusts the formula used to calculate a worker's PIA so that they receive a lower benefit as a percentage of their AIME than they would have if 100% of their earnings had been from Social Security-covered work. More specifically, it adjusts the first 'bracket' of the PIA calculation; instead of using the standard 90% multiplier for the first $1,226 of AIME, the multiplier is reduced to as low as 40%. This results in a reduction of up to $1,226 × (90% – 40%) = $613 in affected workers' PIA amounts.

The WEP penalty is highest for workers with 20 or fewer years in Social Security-covered jobs. However, for those with 21–30 years of covered work, the penalty steps down incrementally each year. Once a worker reaches 30 or more years of covered employment, the WEP penalty is eliminated entirely.

Because the WEP penalty is applied to a worker's PIA itself, it affects all benefits that are based on that PIA number. For example, if a retiree decides to delay filing for Social Security benefits until age 70, their 8%-per-year additional benefit will be calculated on their PIA only after the WEP penalty is subtracted. Likewise, the spousal benefit for the spouse of an individual to whom the WEP applies will be 50% of the WEP-adjusted PIA.

In other words, the WEP penalty can magnify its impact for individuals who decide to delay their Social Security filing and for those with spouses who plan to claim the spousal benefit (though at a maximum, the WEP penalty cannot exceed 50% of the amount that the individual receives from a non-covered pension).

The GPO Penalty On Social Security Spousal Benefits For Non-Covered Pension Recipients

The second 'fairness' issue around the combination of Social Security benefits and payments from non-covered pensions involves the Government Pension Offset (GPO), which affects individuals who receive Social Security spousal or survivor benefits while also collecting a pension from a non-Social Security-covered job.

The original purpose of Social Security spousal benefits was to provide support for households where one spouse was the sole or primary earner (as was overwhelmingly the case in 1935 when Social Security was established). These benefits ensure that a spouse (or ex-spouse) with little or no earnings of their own from which to calculate benefits can receive up to 50% of the primary earner's PIA, while widows and widowers may be entitled to up to 100% of their deceased spouse's PIA.

However, an issue arises when a person works much of their career in non-covered positions (e.g., a state or local government position where no Social Security taxes are paid). For Social Security purposes, these workers are treated as if they have little or no earnings of their own, which means they may be eligible for little to no Social Security benefits under their own name (and the benefits they do have would be further reduced by the WEP, as described above). At the same time, though, they could still be eligible for a spousal benefit based on their spouse's earnings, even while receiving pension payments from their non-covered job.

In 1977, Congress addressed this form of spousal 'double-dipping' by creating the Government Pension Offset (GPO). The GPO reduces the amount of Social Security spousal or survivor benefits an individual can receive if they meet all three of the following criteria:

- They worked at a Federal, state, or local government job where they didn't pay Social Security taxes;

- They qualified for a pension from that job; and

- They are eligible for Social Security spousal or survivor benefits.

At first, the GPO reduced spousal and survivor benefits by 100% of any non-covered pension payments received, but a 1983 modification of the law reduced that amount to 'just' two-thirds of the non-covered payments. As a result, individuals who receive pension payments from non-covered positions can see their spousal benefits severely curtailed by the GPO – to the extent that spouses with relatively high pension payments and relatively low spousal benefits can even see their spousal and survivor benefits eliminated entirely due to the GPO.

Example 3: Edgar, who spent 30 years as a non-covered employee while teaching in a public school system, has retired and receives a monthly pension of $3,000. Edgar's spouse, Frank, worked in the private sector and is now eligible for Social Security benefits of $4,000 per month under his own name.

Assuming both spouses have reached full retirement age, Edgar would be entitled to Social Security spousal benefits of 50% of Frank's benefit, or $4,000 × 50% = $2,000 (before applying the GPO). However, the GPO reduces that spousal benefit by 2/3 of Edgar's non-covered pension, or 2/3 × $3,000 = $2,000.

In other words, the GPO penalty of $2,000 completely offsets Edgar's $2,000 of spousal benefits, reducing them all the way to $0.

If Frank passes away, the GPO would also apply to any survivor benefits Edgar is entitled to receive. Edgar's pre-GPO survivor benefit would equal 100% of Frank's own benefit of $4,000 per month; however, the GPO reduces this amount by 2/3 of Edgar's non-covered pension. So instead of $4,000 per month in survivor benefits, Edgar would receive only $4,000 − (2/3 × $3,000) = $2,000 per month.

The Case For Repealing The WEP And GPO

When the GPO and WEP were passed into law in 1977 and 1983, respectively, the underlying principle of both provisions was about setting a 'fair' level of benefits for workers who spent some number of years paying into a retirement system other than Social Security.

And yet, nearly 50 years later, debate continues over whether these provisions unfairly penalize individuals who spent their careers in non-covered jobs. Many of these jobs – such as police officers and firefighters – carry a greater risk of bodily harm than most jobs, while others, like teaching, are often underpaid relative to their contributions to society. There's an argument that higher Social Security payments for these workers wouldn't represent an unfair 'windfall' but rather extra (and appropriate) compensation for their sacrifices as public servants. Furthermore, penalizing these workers by reducing their Social Security benefits could disincentivize others from pursuing public-sector careers.

Additionally, the calculations for WEP and GPO adjustments are another point of contention. While intended to offset the effects of receiving pension payments from non-covered jobs, they effectively serve as proxy formulas, representing the government's 'best guess' for how a person's Social Security benefits should be adjusted, instead of precise measures of fairness. For example, in most cases the WEP penalty is calculated based on the number of years a worker had “substantial earnings” subject to Social Security rather than the actual size of their noncovered pension. As a result, workers with smaller non-covered pension payments may face disproportionately higher penalties compared to those with larger payments.

Critics argue that, as proxy formulas, the WEP and GPO tend to overcorrect and unfairly reduce benefits for certain subsets of workers. And while there could be ways to restructure the WEP and GPO formulas to mitigate these issues, stakeholder groups like unions representing teachers and police officers have long argued for the complete repeal of both provisions. They contend that public employees who paid Social Security taxes should receive their full Social Security benefits, regardless of their participation in other government pension plans.

Planning for the impact of the WEP and GPO on retirement income has been particularly challenging for affected workers, not just because of the complexity of the formulas but also due to the SSA's inadequate guidance. Pre-retirement Social Security statements simply show each individual's Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) for their full retirement age, unadjusted for the WEP or GPO, with only a vague disclaimer about potential reductions included in a separate block of text on the second page. Many retirees didn't realize their benefits would be reduced due to earnings from non-covered jobs until they received their first Social Security check.

As a result, many retirees (in the case of the WEP) and their spouses (in the case of the GPO) often overestimated the amount of Social Security income they could expect to receive. This left many on much shakier financial ground than they anticipated, forcing them to withdraw thousands more from their supplementary retirement savings each year to make up for the shortfall.

Adding insult to injury, the complexity of the WEP and GPO calculations, along with the SSA's reliance on outside parties to collect the non-covered pension data needed to calculate each retiree's adjustment, frequently led to inaccurate calculations of benefit payments. In some cases, this resulted in a 'clawback' of overpaid benefits once the SSA realized its mistake, creating additional financial stress through no fault of the recipient's own.

The Social Security Fairness Act Repeals The WEP And GPO Retroactive To January 1, 2024

While the WEP and GPO may have, at their core, contained the makings of good policy from the perspective of ensuring fair treatment of benefit calculations for workers across the board, their implementation created significant challenges. For decades, these provisions were difficult to calculate for both recipients and the Social Security Administration (SSA) itself. They were also poorly communicated to individuals, leading to widespread confusion and undermining their ability to effectively plan for retirement. Politically, the WEP and GPO were deeply unpopular, particularly among key constituencies such as police and teacher unions, whose members were disproportionately affected.

In response, Congress passed the Social Security Fairness Act, which passed both the House and Senate on bipartisan votes in late 2024 and was signed into law by President Biden on January 5, 2025.

The Act itself is fairly straightforward: It strikes out the provisions of 42 U.S.C. Sections 402 and 415 that governed the WEP and GPO, effectively repealing both measures. Additionally, it states that those amendments will apply retroactively to any benefit payments made after December 2023.

The upshot of the law, then, is that current Social Security recipients whose benefits were previously reduced by the WEP or GPO – as well as those who would have been impacted in the future – will now receive their full, unreduced benefits going forward. Additionally, Social Security recipients who received reduced benefits since January 1, 2024, will receive retroactive payments for any reduction of benefits during that time.

Example 4: Gerta is a retiree who worked a long career in both Social Security-covered positions and non-covered positions, for which she is now receiving a pension. Up until now, her Social Security payments have been reduced by $500 per month due to the WEP adjustment caused by her non-covered pension.

As a result of the Social Security Fairness Act, however, Gerta's Social Security payments will revert to their full, unreduced amounts going forward. This change will add a total of $500 × 12 = $6,000 to her annual Social Security income (with the actual amount increasing each year by annual COLA adjustments).

Additionally, Gerta will receive a retroactive payment from the SSA for all of her WEP adjustments dating back to January 1, 2024. Assuming the SSA starts issuing her full Social Security payments in June 2025, Gerta will receive a back payment of $500 × 18 = $9,000 for those adjustments.

While the Social Security Fairness Act eliminates the WEP and GPO, several unanswered questions remain as the SSA determines how to implement the changes. These include:

- Timing: When will the increased benefits begin to appear in affected recipients' Social Security checks?

- Retroactive Payments: How will the retroactive adjustment for benefits going back to January 2024 be handled? Will it be included in monthly checks or paid in a lump sum?

- Application Process: Will the retroactive payment be paid automatically, or will recipients need to submit a separate application?

- Eligibility For New Applicants: Will applicants who never applied for spousal benefits because they would have been eliminated by the GPO be eligible for retroactive payments?

- Deceased Beneficiaries: Will retroactive payments be available for WEP- or GPO-affected Social Security recipients who have passed away since January 2024?

As of this writing, the SSA's website for the Social Security Fairness Act recommends that Social Security recipients only ensure that their mailing address and direct deposit information are up-to-date. Public pension recipients who have not yet filed for Social Security benefits may also want to consider doing so. However, the site will hopefully be an important resource in the coming months as the agency provides additional information about how the Fairness Act will be implemented. Monitoring updates closely can help recipients stay informed about these changes.

Planning Considerations For The Repeal Of The WEP And GPO

The passage of the Social Security Fairness Act is good news for individuals who are impacted by the WEP or GPO, whether currently or in the future. In some cases, this repeal will substantially boost their benefits and possibly even be enough to prompt some families to reconsider their plans for work and retirement.

Identifying Clients Who Will Benefit From The Repeal Of The WEP And GPO

For advisors, the first step is to identify which clients are currently affected by the WEP and/or GPO. Broadly, this conceivably includes anyone who worked in a non-covered position and receives pension payments from that work. For example, retired teachers, police officers, firefighters, Federal workers hired before 1983, and some expats or foreign workers who receive pensions from other governments.

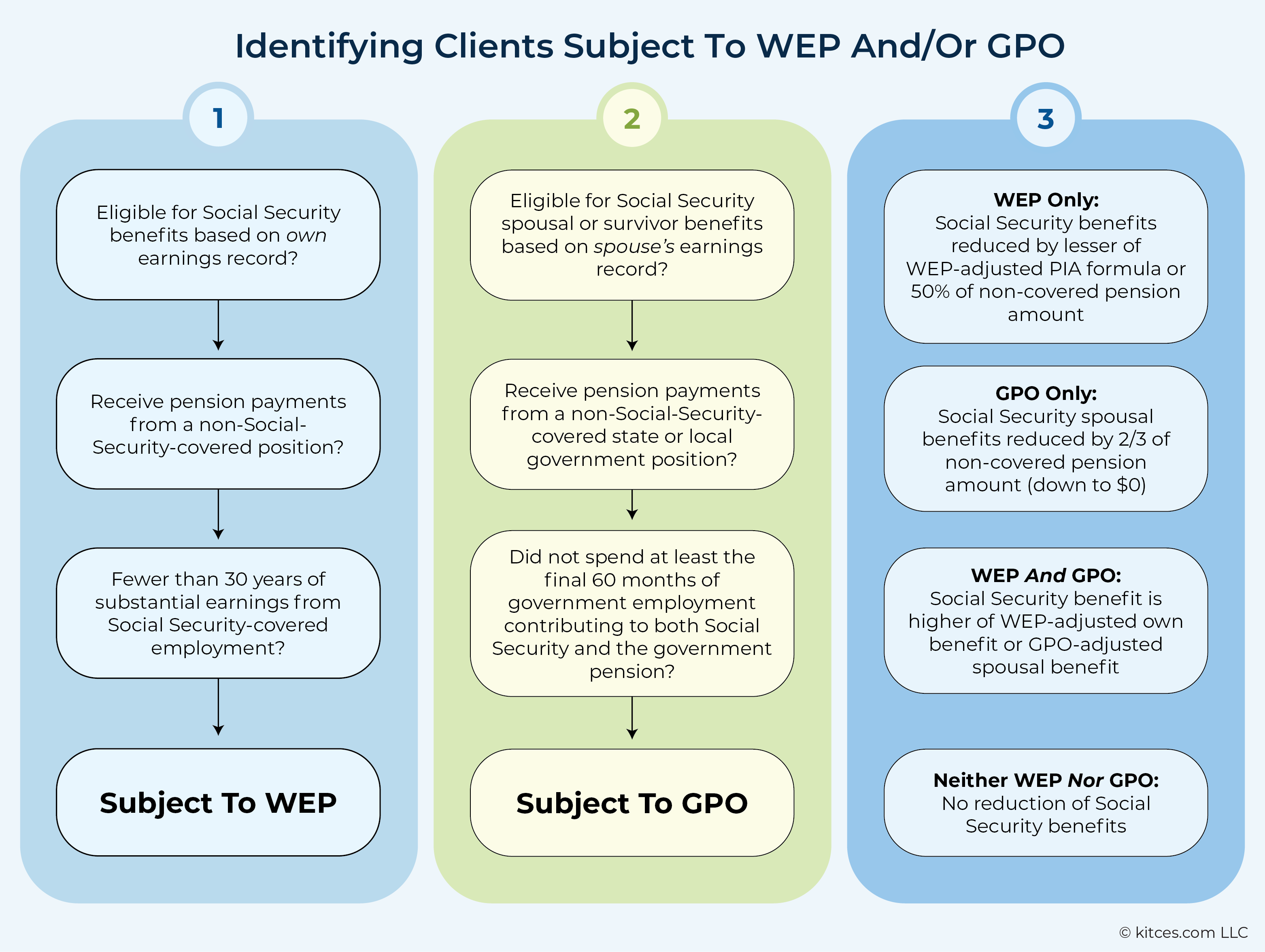

However, not all such clients will see an increase in benefits from the repeal of the WEP and GPO. For example, some state and local government employees may qualify for an exception to the GPO known as the “Last 60 Months Rule”. This rule applies if the client spent at least the last 60 months of their government employment working in a position covered by both Social Security and the government pension system. These clients won't be subject to GPO to begin with, so they won't see any increase in benefits from its elimination.

Workers who held relatively short or part-time roles in non-Social Security-covered jobs but still qualified for pension payments from those positions may also be unaffected by the repeal if they have 30 or more years of earnings in Social Security-covered positions, which exempts them from the WEP penalty.

Notably, while some individuals might be subject only to either the WEP or GPO, others could be subject to both, in which case the Social Security benefit they're currently entitled to is simply the higher of their WEP-reduced "own" benefit or their GPO-reduced spousal benefit.

For clients who may be subject to WEP and/or GPO, then, advisors can go down the lists of respective criteria for both penalties, as shown below, to determine whether the client is subject to WEP, GPO, both, or neither.

Estimating Social Security Increases After The Repeal Of The WEP And GPO

The actual amount by which Social Security payments for those affected by the WEP and GPO varies for each individual. For those impacted by the WEP, the increase depends on the number of years that the recipient had substantial income subject to Social Security taxes. For those impacted by the GPO, the increase depends on the amount of the public pension payments they receive. However, it's possible to gauge the impact of the WEP and GPO's elimination on a broad level.

Consider that, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the median state or local government pension received by an individual age 65+ in 2023 was $24,770 per year. Since the GPO reduces Social Security spousal benefits by two-thirds of the pension amount, it can be deduced that a recipient of the median government pension amount would lose up to 2/3 × $24,770 = $16,513 per year, or $1,376 per month, in Social Security spousal benefits. In cases where the spousal Social Security benefit was less than this amount, the GPO would have completely canceled it out.

Also consider that, as mentioned earlier, the maximum WEP reduction from an individual's PIA in 2025 is $613 per month or $7,356 per year. In this case:

- If the worker's spouse receives spousal benefits, the total monthly household reduction would include an extra 50% of the WEP penalty, or 50% × $613 = $306.50 ($3,678 per year).

- If the worker delays their Social Security filing until age 70 to claim the maximum benefit increase of 8% per year from ages 67 to 70 (four years), they would lose an additional $613 × (4 × 8%) = $196.16 per month, or $2,353.92 per year.

Added all together, a person with the maximum WEP reduction, whose spouse also claims the spousal benefit, and who delays their Social Security filing until age 70, loses $613 + $306.50 + $196.16 = $1,115.66 per month, or $13,387.92 per year. Conversely, after the repeal of the WEP, they'll have an additional $13,387.92 of income per year going forward.

For individuals who haven't yet filed for Social Security benefits, it can be fairly easy to find out what their Social Security benefits will look like without the effects of the WEP and GPO. The individual's Social Security statement, which can be pulled directly from their account on the Social Security website, shows an individual's projected PIA, with no adjustment for the WEP. A person who expects to be subject to the WEP, then, can look at their own Social Security statement, which already reflects their estimated PIA without the WEP. The PIA can also be used to calculate their spouse's spousal benefit (50% of the PIA) and the amount that they can expect to receive if they either file early for a reduced benefit or delay filing for an increased benefit. Similarly, someone who expects to be subject to the GPO can use their spouse's Social Security statement to calculate their own spousal benefit based on 50% of their spouse's PIA.

Filing For Spousal And Survivor Benefits After The GPO Repeal

For many Social Security recipients, the increased benefits from the Social Security Fairness Act will be applied automatically once the Social Security Administration (SSA) updates its systems to align with the new law. However, that's only the case if they've already filed for benefits.

There may be many people with income from non-covered pensions who, knowing that their Social Security spousal or survivor benefits would be reduced to $0 under the GPO, never filed for benefits that they wouldn't have received anyway. Now that the GPO has been repealed, these individuals may be entitled to Social Security spousal or survivor benefits – but only if they file for them. Without filing, they won't receive the higher spousal or survivor benefits they are now eligible for.

For advisors, it's essential to identify clients who might fall into this category and reach out to them to ensure that they file their application for spousal benefits. This includes those who:

- Have income from a state or local government pension;

- Have a current or former spouse who receives Social Security benefits under their own name (or a deceased spouse who did or was entitled to receive benefits); and

- Do not currently receive any spousal or survivor benefits.

Nerd Note:

Social Security rules allow individuals and spouses who have reached full retirement age to file for retroactive benefits going back up to six months before the date the application is submitted (or 12 months in the case of some disability claims). Because the repeal of the WEP and GPO is effective as of January 2024, individuals applying for spousal or survivor benefits for the first time can claim retroactive benefits for up to six months before filing.

It's unclear whether a person filing for retroactive benefits today will immediately receive their full (non-GPO-reduced) retroactive payment, or if they will need to wait until the SSA pays retroactive benefits to all WEP- and GPO-impacted recipients – more guidance is likely to come.

Switching From Own Social Security Benefits To Spousal Benefits After GPO Repeal

Even individuals currently receiving Social Security benefits under their own name (already reduced by the WEP) may want to consider filing for spousal benefits. In some cases, it's possible that a person's spousal Social Security benefit will be higher than their own after the WEP and GPO are repealed.

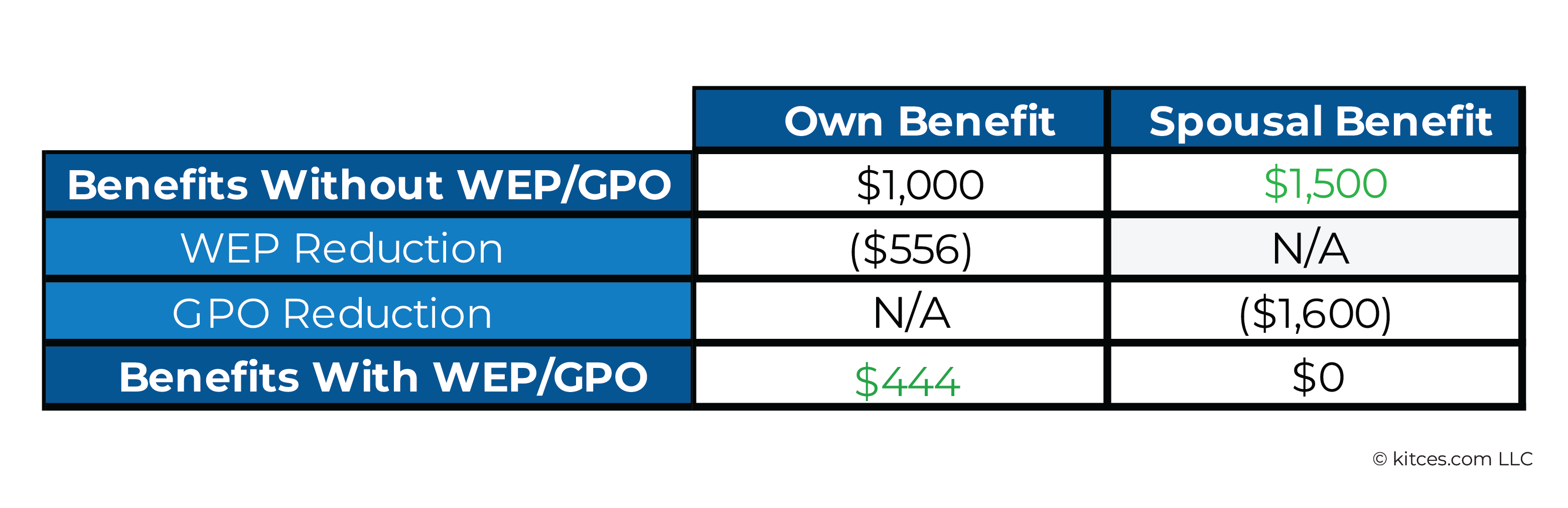

Example 5: Henrietta and Ike are a married couple, both age 70. Ike began receiving Social Security benefits under his own name at age 67 and receives $3,000 per month. Henrietta, a retired police officer, receives a non-covered pension of $2,400 per month.

Henrietta is eligible for Social Security benefits under her own name, with a pre-WEP benefit of $1,000 per month. After the WEP reduction, though, she only receives $444.44. Normally, Henrietta would also be entitled to Social Security spousal benefits of 50% of Ike's benefits, or $3,000 × 50% = $1,500 per month. But due to the GPO, she needs to reduce that amount by 2/3 of her non-covered pension. Since 2/3 × $2,400 = $1,600 is greater than the pre-GPO spousal benefit of $1,500, Henrietta's spousal benefit is reduced to $0. Because her own Social Security benefit is $444.44, it's better for her to receive benefits under her own name.

After the passage of the Social Security Fairness Act, Henrietta's Social Security benefits are fully restored. Her own benefit increases to $1,000, and her spousal benefit is restored to $1,500. Since her spousal benefit is higher than her own, it makes sense for Henrietta to switch from her own benefit to the spousal benefit.

Reevaluating WEP/GPO Reduction Strategies After The Repeal

Before the repeal of the WEP and GPO, some workers went to great lengths to reduce the impact of these provisions. For some, these strategies made the difference between WEP- or GPO-reduced Social Security income and their un-reduced benefits worth the effort.

In many cases, the strategy involved working for more years, even in a reduced or part-time role, in order to reduce the impact of the WEP and GPO. For instance, workers subject to the WEP could reduce the WEP penalty on their own income by working additional years in a Social Security-covered position if the total number of years in which they earned substantial earnings was more than 20 (and they could eliminate the WEP entirely if they had at least 30 years of substantial earnings). For spouses subject to the GPO, the penalty could be avoided by spending at least the final 60 months of their work in a state or local government role in a position that contributed to both Social Security and the noncovered pension, providing future retirement payments to the worker.

Now that the WEP and GPO have been repealed, there is no longer any need to keep working solely for the purpose of reducing penalties. However, continuing to work more years in Social Security-covered positions may still increase future Social Security benefits by raising the worker's AIME. At the same time, the extra cash flow from now-unreduced Social Security benefits may make it possible for some individuals to retire earlier, even without the additional years of work history!

For Social Security recipients whose benefits have been reduced by the WEP and GPO – and for those planning to file soon – the Social Security Fairness Act represents a true windfall in retirement income. For many, this change will allow them to retire earlier and/or provide greater financial comfort in retirement.

However, these additional benefits today do come at a cost. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the bill will add $196 billion in benefits paid over the next 10 years, accelerating the projected timeline for the exhaustion of the OASI Trust Fund, which is already on track to pay 100% of scheduled benefits only until 2035. The additional costs also compound the impact of the incoming Trump administration's proposal to eliminate Federal income taxation of Social Security benefits, which is being considered as a part of upcoming legislation to replace the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act when it sunsets at the end of 2025.

While the Social Security Fairness Act is good news for current and near-future retirees, it does create longer-term uncertainty for those with retirements further off. In the coming years, Congress may take steps to restrict benefits for future retirees to address Social Security's financial challenges – potentially even restoring some version of the WEP and GPO, which were originally created in the wake of a similar Social Security solvency crisis in the 1970s and 1980s.

The bottom line is that laws and regulations that impact financial planning are never set in stone. While some changes simplify planning and others make it more complex, the only certainty is that more changes will come. Which makes it all the more important for advisors to help clients build plans that are agile in the face of uncertainty and to be prepared to guide them through changes as they arise!

Leave a Reply