Executive Summary

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) have become an increasingly popular tool for financial advisors and their clients due in part to the 'triple tax savings' they offer: tax-deductible contributions, tax-free growth, and non-taxable distributions for qualifying expenses. However, HSAs require individuals to be covered by a High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP), which has tradeoffs compared to traditional health insurance plans. Which means that financial advisors, with their knowledge of clients' personal and financial circumstances, are uniquely positioned to evaluate these tradeoffs and help clients balance healthcare costs and savings to align with their financial plans.

While HDHPs are often expected to come with higher deductibles than traditional plans, these deductibles may be higher than they appear. For instance, HDHP deductibles and out-of-pocket limits apply only to in-network coverage, with out-of-network care subject to higher maximums. Additionally, HDHPs typically apply deductibles to nearly all medical services (except preventative care), unlike traditional health plans that often feature fixed copays for prescriptions, specialist visits, and emergency room care. Many HDHPs also use aggregate deductibles, requiring the entire family deductible to be met before coverage begins for any individual – which can lead to higher out-of-pocket costs, particularly when one family member incurs most of the expenses.

Traditional health plans, on the other hand, often provide features that make them more attractive for individuals with moderate or predictable medical costs. For example, traditional plans often come with separate out-of-pocket maximums for prescription drugs and other medical services (while HDHPs typically have a unified maximum) or offer tiered health networks that provide discounts for specific in-network providers. Furthermore, because HSA eligibility requires coverage exclusively under an HDHP, clients nearing Medicare age or those with other disqualifying coverage may need to weigh the benefits of HSA contributions against other health plan options.

While the 'triple tax savings' of HSAs is one of their most attractive features, those with traditional health plans can also benefit from tax-free premiums, which may result in greater tax savings compared to HDHPs with lower premiums. Clients with traditional plans can also take advantage of Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs), which allow for tax-free contributions and reimbursements (though, unlike HSAs, any unused funds remaining in the FSA are forfeited at the end of the plan year). Combined with the potential cost savings from lower deductibles and total out-of-pocket costs – which could be invested in taxable accounts – clients with higher medical expenses and in lower tax brackets may find that traditional health plans offer a better balance of savings and healthcare coverage.

Ultimately, while HSAs offer significant tax advantages, advisors can play a key role in helping clients weigh these benefits against the potentially higher costs of HDHPs. By aligning healthcare and financial planning, advisors can demonstrate their ongoing value to their clients by helping them choose the plan that best supports their goals – and their peace of mind – while maximizing both annual and long-term cost savings!

Since their creation in 2003, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) have become an increasingly popular tool for financial advisors, consumers, and employers. HSAs are individually funded accounts that offer the tantalizing 'triple tax savings' of tax-deductible contributions, tax-free growth, and non-taxable distributions (when used for qualifying expenses). However, to open and contribute to an HSA, individuals must be covered by a High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP), which serves as the required pairing for HSA eligibility.

From an employer's perspective, HDHPs offer a low-cost healthcare option with manageable premiums for both employers and employees. These cost savings can either be retained by the employer or passed along to employees through company contributions to their HSAs. For employees, HDHPs provide lower premiums and the opportunity to leverage the significant tax benefits of an HSA.

But the benefits of HSAs come with trade-offs. The aphorism "You get what you pay for" often holds true in health insurance, as the IRS's strict eligibility requirements for HSAs mean that HDHPs must meet strict rules that limit how consumers can cost-share medical expenses. While HDHPs typically offer lower premiums than traditional health plans, they require individuals to self-insure a larger portion of their healthcare costs by trading lower up-front premiums for higher out-of-pocket expenses when they need medical care.

For some, the higher deductible of an HDHP is an acceptable price for gaining access to an HSA. This is particularly true for those who can self-insure against the higher out-of-pocket costs, save and invest HSA contributions for the future, and currently have minimal healthcare needs (and thus lower medical bills). For others, the trade-offs of an HDHP may outweigh the tax savings of an HSA. Consumers with higher medical expenses may save more by choosing a health plan that is better suited to their needs and redirecting the premium savings into other financial goals.

Financial advisors, with their unique knowledge of clients' personal and financial circumstances, are well-positioned to analyze the costs and benefits of competing health plans. By analyzing available options, advisors can help clients find the right balance of healthcare costs and savings to align with their overall financial plans in the short and long term.

Breaking Down The High Deductible: Why The "High Deductible" Is Even Higher Than It Appears

Advisors can begin by helping their clients understand the mechanics of High Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs) and how they relate to their personal health situations. While clients may be familiar with the high deductibles of HSA-eligible health plans through their company benefit guides or personal research, the details can often be confusing. Misunderstandings about how and when the deductible actually applies are common as clients navigate a maze of nuances and regulations surrounding HDHPs.

HDHP Limits Only Apply In Network

To control the costs of HDHPs, the IRS sets both minimum deductibles and maximum out-of-pocket limits each year as required by Congress. However, how these limits are applied has been addressed in numerous IRS notices and amended by Congress since HSAs were first established. In addition, because these legislated minimums and maximums only set boundary conditions, the specific details of HDHPs – such as deductible amounts and out-of-pocket maximums – vary widely from plan to plan.

Notably, IRS Notice 2004-2 Q&A-4 clarified that the legislated deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums for HDHPs apply only to in-network coverage. Since insurers rarely, if ever, set lower deductibles for out-of-network providers, this means that clients using out-of-network care under an HDHP are likely to face both higher deductibles and (much) higher out-of-pocket maximums. In extreme scenarios requiring out-of-network care, the financial stakes can be significantly higher than clients may anticipate.

Example 1: Sandra is giving birth at Health First Hospital, covered by her employer's HDHP, with a $6,000 in-network out-of-pocket limit.

Despite careful planning, Sandra cannot find a reputable pediatrician in her plan's network for her newborn's follow-up care. As a result, she faces up to her plan's out-of-network maximum of $12,000 for her baby's circumcision, sick visits, and follow-up testing – even though she has already met her in-network out-of-pocket limit with the delivery and hospital stay.

Nerd Note:

Before the No Surprises Act became effective in 2022 (passed as part of the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act), patients with HDHPs could unexpectedly face balance billing for out-of-network providers contracted through in-network facilities. For instance, an in-network hospital might use an out-of-network anesthesiologist or radiologist, leaving the patient responsible for additional charges beyond what their insurance would cover. The No Surprises Act now limits these surprise bills by requiring insurers to apply in-network cost-sharing rules in many of these scenarios, reducing financial shocks for patients.

HDHP Deductibles Apply To Nearly Everything (With No Caps On Certain Services)

To qualify as an HDHP, plans must apply the deductible towards virtually all medical services except for preventative care. This contrasts as a notable disadvantage over traditional health plans, which often offer fixed copays for prescription drugs, specialist visits, and emergency room care that are exempt from the in-network deductible.

Example 2: Sonya's OB-GYN prescribes Bonjesta to help her manage her prenatal nausea. The retail cost of Bonjesta is $800 at her local pharmacy.

On her employer's HDHP, Sonya must pay the full retail cost of $800 for her monthly prescription until she reaches her $1,650 deductible. Once her deductible is met, she will owe a 20% coinsurance payment on future prescriptions or medical services.

If she had elected her employer's PPO plan instead of the HDHP, Sonya's costs for specialty drugs would have been capped at a $100 fixed copay per prescription each month.

While some HDHPs offer fixed copays for prescriptions in lieu of a coinsurance percentage, these copays only apply after the plan's annual deductible is met, as required by IRS rules. This structure can make HDHPs less appealing for clients who may require frequent medication refills or ongoing care.

Although HDHPs still offer zero-deductible benefits for preventative care, the scope of these services is narrowly defined under Section 1861 of the Social Security Act to include only routine health evaluations, immunizations, and specific screenings. Traditional health plans often go further, covering a wider range of services as fully subsidized 'freebies' at no cost, subject only to the plan's requirements.

And while zero-deductible allowances for HDHPs were temporarily expanded by Congress to include telehealth and remote care under the CARES Act and the 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act, these provisions expired at the end of 2024 – forcing individuals enrolled in HDHPs to adapt to increasingly restrictive coverage going into 2025.

Most HDHPs Use Aggregate (Not Embedded) Deductible Systems

One notable quirk of HDHPs is how their deductible systems work, especially for those enrolled at the family coverage levels.

Traditional health plans typically utilize an embedded deductible system, where the plan begins to cover costs for any family member who meets their individual deductible. This structure effectively treats a family plan as an extension of the plan's single coverage, allowing cost-sharing to start sooner for individuals within the family.

By contrast, HDHPs are typically forced into an aggregate deductible system, which requires that the entire family deductible be met before the plan pays for any covered individual. This less favorable system is a consequence of the HSA requirements under IRC Section 223(b)(2)(B), which mandate higher deductibles for individuals with family HDHP coverage. Which means that, in practice, deductibles on HDHPs are often three to four times higher than those on traditional health plans when viewed in aggregate versus embedded systems.

Example 3: Natasha's health plan options include an HDHP with a $2,000 individual deductible and an aggregate $4,000 family deductible, as well as a PPO plan with a $1,000 individual deductible and an embedded $2,000 family deductible.

Since Natasha has selected the family HDHP option, the entire $4,000 family deductible must be satisfied by Natasha or her family as a whole before any cost-sharing benefits begin.

Therefore, when Natasha's spouse incurs $1,000 in medical expenses, and Natasha incurs $2,500, the family still needs to pay an additional $500 out-of-pocket before the HDHP begins sharing costs.

By contrast, if Natasha had chosen the PPO plan, the PPO's embedded deductible would have allowed cost-sharing to begin once the $1,000 bill for her spouse's expenses was paid, even though the family hadn't met the $2,000 family deductible.

For families where only one member requires significant care, the HDHP's aggregate deductible can result in much higher out-of-pocket costs. In Natasha's case, her family must pay up to four times more out-of-pocket under the HDHP compared to the PPO plan!

For families with high healthcare expenses spread across multiple individuals, the aggregate deductible system may not be as problematic since the family-level deductible will eventually be met. Similarly, for single individuals with no dependents, the difference is irrelevant. But for families with high healthcare needs that are heavily skewed towards one individual – as is often the case – the aggregate deductible system can pose significant challenges.

Even beyond the deductible system, other differences between HDHPs and traditional health plans, discussed next, may also influence whether an HDHP is the right choice.

Beyond The Deductible: Why HSA Eligible Plans Are More Expensive Than They Seem

Even with the higher and more broadly applicable deductible, an HDHP can still seem to be an attractive option, particularly on either extreme of the spectrum of health needs. For individuals with low medical expenses, the reduced health benefits of an HDHP may be a non-issue, and paying higher premiums for a traditional plan could feel like throwing money away by over-insuring.

On the other hand, high medical users may still find HDHPs competitive. With lower up-front premiums, a potential employer contribution to an HSA, and an out-of-pocket maximum that caps catastrophic costs (as long as the plan's network is adequate), HDHPs can still be a compelling choice, even without the fixed copays offered by traditional health plans.

However, for those with moderate or predictable medical expenditures, HDHPs may not always be the best choice. In many cases, traditional health plans can better control out-of-pocket costs with features like lower deductibles, fixed copays, or broader coverage options.

HDHPs Have Higher Out-Of-Pocket Limits That Apply To Medical Services And Prescriptions

A common cost-controlling mechanism found in traditional health plans is the use of separate out-of-pocket maximums for prescription drugs and other medical services. By comparison, HDHPs typically feature a single, unified out-of-pocket maximum that applies to both medical services and prescription drugs.

Example 4: Alonzo takes Trintellix (Vortioxetine) for his depression, which costs $500 for a monthly prescription.

Unfortunately, neither of Alonzo's health plans offers Trintellix for a fixed copay. However, his PPO plan caps his out-of-pocket costs for prescriptions to just $1,500 per year, compared with the $4,000 out-of-pocket maximum for other medical services.

Meanwhile, the HDHP has a $5,000 unified out-of-pocket maximum for both medical services and prescription drugs.

Note that, as in Alonzo's case above, having a separate out-of-pocket maximum for prescription drugs can be both a disadvantage and an advantage. The disadvantage is that if Alonzo incurs significant costs for other medical services and prescription drugs in the same year, the HDHP's single, combined out-of-pocket maximum may result in lower total costs since he only needs to meet one cap for the year! But if most of his medical expenses come from prescriptions, the PPO plan's prescription drug cap could save him thousands of dollars each year compared to the HDHP.

No Tiered Health Networks For Preferred Networks

In addition to offering multiple out-of-pocket maximums, traditional health plans may also seek to control costs by offering tiered health networks. These plans discount a subset of in-network providers that affiliate more closely with the insurer to further reduce costs. Thus, a plan may provide a tiered network system that allows covered individuals to access care at a reduced copay or coinsurance percentage for one network, a higher copay or coinsurance for another, and still higher amounts for care received outside of both networks.

Because HDHPs must comply with minimum deductible requirements across all health networks, they are unlikely to provide a similar discounting structure to their traditional health plan counterparts. As a result, tiered health plan structures are typically reserved for non-HDHP alternatives.

Example 5: Mabel's PPO plan offers two tiers of in-network coverage:

- A $250 deductible for care received at her local university-sponsored hospital facilities (the preferred tier); or

- A $1,000 deductible for care within the broader BestCare network offered in her state.

She also has an HDHP option with a $1,650 deductible for all in-network providers.

If she chooses the HDHP plan, she would be required to pay an additional $1,650 – $250 = $1,400 out-of-pocket before receiving any coinsurance benefits on the HDHP versus what she'd pay on the PPO plan's discounted university network.

While this advantage of her PPO plan is immaterial if Mabel receives all of her medical care from the broader network of providers, she could realize significant savings by staying within the smaller university health network – a benefit she would forfeit if she chooses the HDHP instead.

Restrictions On Alternative Coverage Options – Including Medicare

Beyond limitations like multiple health networks or tiered out-of-pocket maximums, individuals wishing to qualify for an HSA may need to eschew valuable secondary health coverage. Under IRC Section 223(c)(1)(A)(ii)(I), to be eligible for HSA contributions, an individual not only must be covered by an HDHP but also must not be covered by any other disqualifying health plan.

In practice, this means that to maintain HSA eligibility, individuals must often forsake secondary health plans, including coverage through a spouse or parent, Medicaid, or Medicare. Even Medicare Part A, which is typically premium-free for eligible individuals, is considered disqualifying for HSA eligibility.

Example 6: Harold turns 65 next month and remains eligible for his employer's HDHP coverage. In order to maintain HSA eligibility, he must do the following:

- Delay enrolling in all four parts of Medicare (A, B, C, and D) until retirement;

- Postpone Social Security benefits, which would otherwise trigger automatic Medicare enrollment under IRS Notice 2004-50, Q&A-2; and

- Ensure he is not covered by his spouse's health plan as secondary insurance unless it is also an HDHP.

Even if Harold is willing to delay both Medicare and Social Security to continue making HSA contributions, this choice comes at a steep price – given that Part A provides valuable hospital coverage, typically with $0 out-of-pocket premiums, and, depending on the affordability of his spouse's health insurance, his spouse's plan may offer valuable secondary coverage that he would also need to forgo.

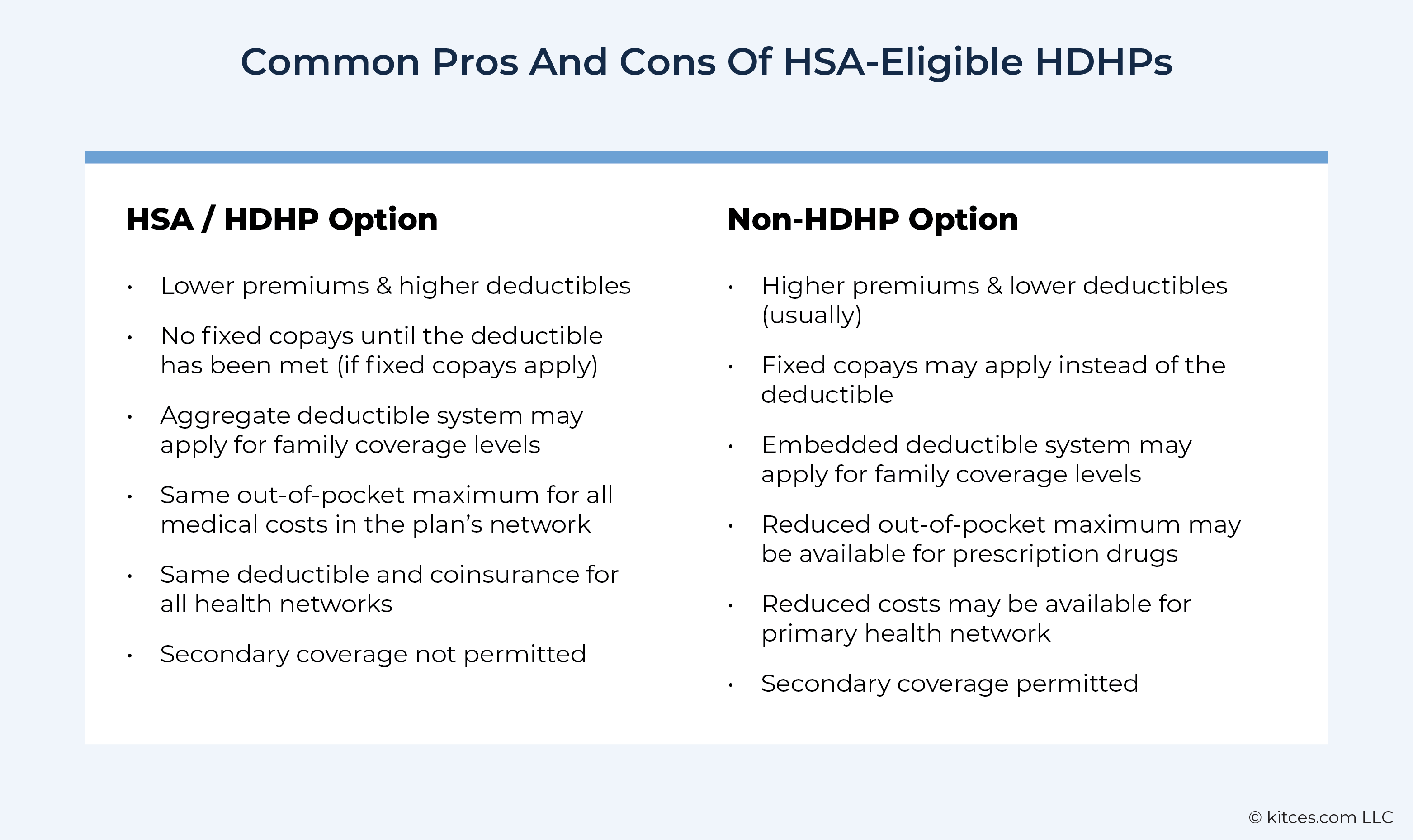

When considering these trade-offs, it's helpful to weigh the general advantages and disadvantages of HSA-eligible HDHPs. These plans often feature lower premiums, higher deductibles, and unified out-of-pocket maximums, while non-HDHPs may offer greater flexibility through tiered networks, embedded deductibles, and secondary coverage options.

Comparing Plans: When Other Options Can Offer Equal (or Greater) Tax Savings

HSAs offer valuable tax savings, which can help offset the potential drawbacks of HDHPs. However, because the drawbacks vary widely on individual circumstances, it's important to carefully evaluate whether an HDHP – and the accompanying HSA – is truly the best option.

Tax Savings Beyond HSAs: The Advantages Of Tax-Free Premiums And FSAs

HSAs can provide substantial tax savings, particularly for high-income individuals. For example, at a 37% Federal income tax rate, someone making the maximum family contribution of $8,550 to their HSA in 2025 would save over $3,000 in Federal income taxes alone. Additionally, state and local income tax savings may apply, as well as Medicare and Social Security taxes (if wages fall below the Social Security wage base).

However, these tax savings are not unique to HSAs. In fact, similar tax savings are available through many health insurance plans. For example, health insurance premiums are typically paid with pre-tax dollars, offering a significant and widely accessible tax advantage to anyone covered under an employer-sponsored plan. This feature applies broadly and doesn't require enrollment in an HSA or HDHP. Additionally, Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) offer another way to achieve tax savings on qualifying medical expenses for non-HSA users. FSAs allow for tax-free contributions and reimbursements, similar to HSAs. However, FSAs are more restrictive because of the 'use-it-or-lose-it' rule, which generally requires any unused funds to be forfeited at the end of the plan year.

In essence, HSAs retain the tax-free benefits of traditional health insurance but essentially rely on a self-insurance model. This structure shifts a greater share of medical expenses onto consumers via HDHPs, allowing consumers to reimburse themselves from their own savings instead of relying on insurance company reimbursements. While HSAs offer unique flexibility and long-term savings potential, other options – such as tax-free premiums and FSAs – can provide meaningful alternatives.

The Value Of HSAs: Are They Right For Long-Term Growth?

HSAs offer long-term growth potential, but only if contributions are saved and invested rather than spent on frequent medical reimbursements. A depleted HSA, regularly used for immediate expenses, may significantly reduce or even negate the financial advantages of choosing an HSA-eligible HDHP.

This makes it critical for individuals to evaluate whether they have the means – and the discipline – to save and invest HSA funds for the future. Those who lack an adequate emergency fund or prefer to use their HSAs for ongoing medical expenses may never realize the full tax savings potential. For these individuals, enrolling in a traditional health plan may be a better choice, as the upfront costs of an HDHP paired with an underutilized HSA could outweigh any tax benefits.

Nevertheless, HSAs offer a key advantage over both traditional health plans and FSAs: contributions can (and often should) be saved and invested for long-term, tax-free growth. Unlike FSAs, which follow a 'use-it-or-lose-it' system, HSAs allow for indefinite accumulation, potentially resulting in significant growth over time. When paired with tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses, this creates a powerful compounding effect.

But if the additional out-of-pocket health expenses paid out of pocket as a consequence of enrolling in an HDHP are high enough, the tax savings and growth benefits of an HSA will quickly be outpaced by the incumbent costs of the HDHP – such that one would be better off enrolling in a traditional health plan and investing their savings in a taxable account instead.

Comparing The Costs And Savings Of HSA And Non-HSA Plans

When evaluating the potential savings of HSA-eligible HDHPs versus non-HSA plans, it's essential to consider both short-term out-of-pocket costs and long-term tax advantages. The following example highlights how these factors can impact the financial outcomes of individuals with varying healthcare needs and saving priorities.

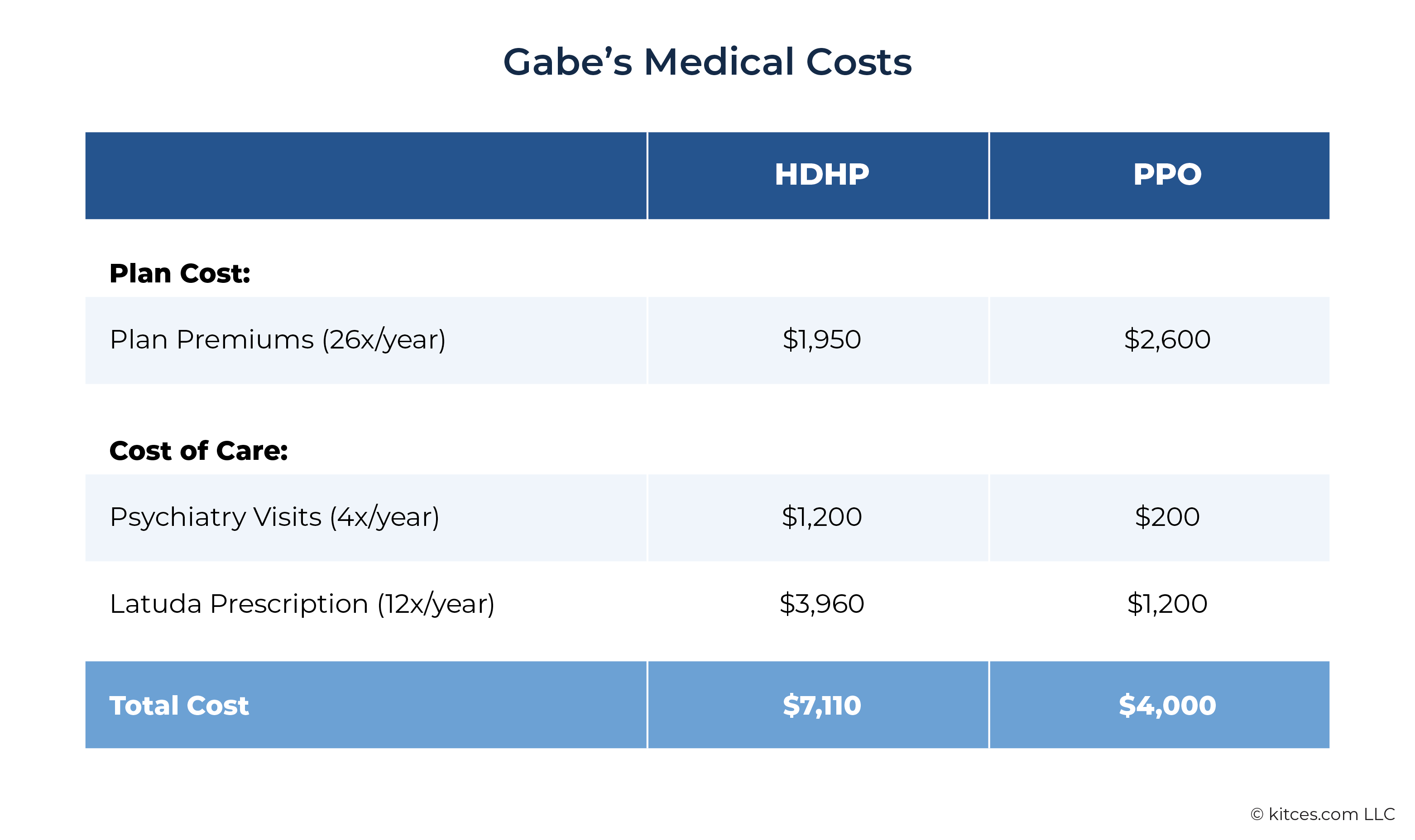

Example 7: Gabe is a 35-year-old single man who receives ongoing treatment for bipolar disorder. His psychiatrist prescribes Lurasidone (Latuda), which retails for $1,500 per month. Gabe also schedules psychiatry visits every three months at $300 per visit. Aside from his mental health needs, Gabe has no significant medical expenses.

Gabe's employer offers two plan options:

- An HDHP with a deductible of $1,650, 20% co-insurance, an out-of-pocket maximum of $8,300, and a $75 bi-weekly premium.

- A PPO plan with a $50 fixed copay for psychiatry visits, a $100 maximum copay for specialty prescription drugs, and a $100 bi-weekly premium.

Gabe's annual medical costs break down as follows:

Because Gabe benefits from fixed copays for his psychiatry visits and prescriptions, he saves an impressive $7,110 – $4,000 = $3,110 each year by enrolling in the PPO plan instead of the HDHP, given his current plan structure and medical costs.

Barring any dramatic changes to Gabe's treatment plan, benefits package, or job, his situation is unlikely to change in the near future. Therefore, it is important for him to consider whether enrolling in an HDHP is worthwhile for the long-term savings potential offered by an HSA.

Example 8: Gabe, from Example 7, recognizes that the PPO plan is clearly the better choice for short-term medical expenses, but he also wants to consider the benefits of enrolling in the HDHP in order to contribute to an HSA, which he plans to save and invest for his retirement at age 65.

If he were to enroll in his employer's HDHP, Gabe would make maximum contributions to the HSA each year, beginning with a 2025 contribution of $4,300. Assuming that contribution limits will increase with inflation (3%) each year and that Gabe will invest his contributions at an 8% annual rate of return, after 30 years, he'll have an estimated tax-free HSA balance of $719,613 when he retires at age 65, which he can use for qualified medical expenses in retirement.

By contrast, if Gabe were to enroll in the PPO plan and invest the same $4,300, increasing annually with inflation, into a taxable account, earning 6.8% after a 10% tax drag, he would end up with $627,643 after 30 years. This would equate to an after-tax value of just $569,261 after paying taxes on his taxable gain of $389,211 at the 15% tax rate applicable to long-term capital gains.

At first glance, it appears that Gabe would be much better off choosing an HSA, ending with almost $200,000 of additional potential after-tax savings! However, the picture changes when accounting for the annual cost savings that Gabe could realize from using the PPO plan.

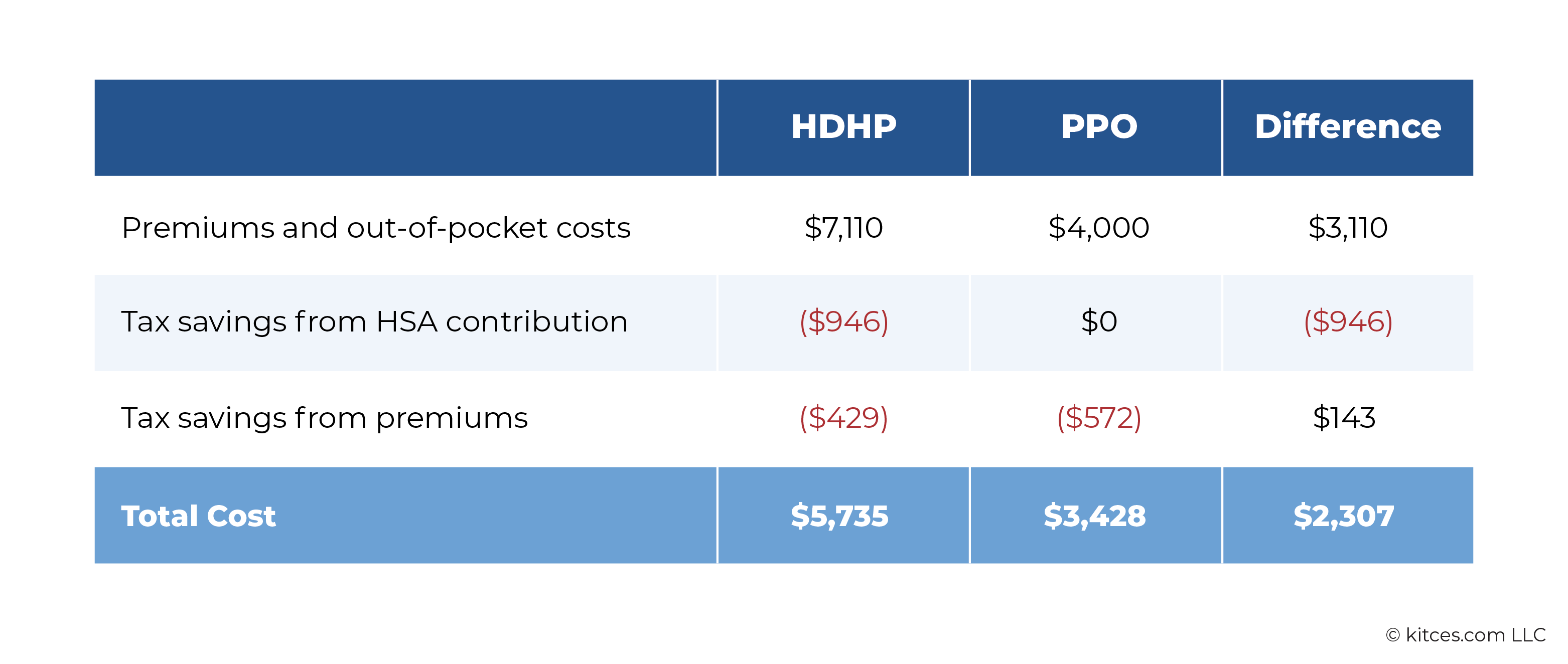

As shown in Example 7 above, Gabe saves $3,110 per year on his cumulative premiums and out-of-pocket costs with the PPO plan. However, that amount is reduced by the annual tax savings that Gabe, who is in the 22% tax rate, would have realized by contributing to the HSA of $4,300 × 22% = $946.

Additionally, the difference between the tax savings from the deductibility of premiums for each plan also affects the total cost of each option: $1,950 × 22% = $429 for the HDHP, and $2,600 × 22% = $572 for the PPO.

In total, the annual cost savings of using the PPO instead of the HDHP add up to $2,307, as summarized below:

If Gabe reinvests his $2,307 of surplus savings (increasing for inflation) from taxes and out-of-pocket medical costs into his brokerage account each year, along with the $4,300 that he would have contributed to his HSA, he'll end with $964,381 in his brokerage account at retirement, equating to an after-tax value of $874,677. Which exceeds the potential after-tax value of his HSA by $155,064, equating to $63,844 in today's dollars!

As Examples 7 and 8 above show, the PPO plan is the better choice for Gabe in both the short and long term. However, this may not be the case for others with different circumstances. For instance, individuals in higher tax brackets may find an HSA more favorable, particularly if they can contribute the maximum and benefit from the tax savings. By contrast, the higher tax drag on investment returns in a taxable brokerage account can make such alternatives less appealing. But if other tax-advantaged retirement accounts are available and can be fully funded instead of an HSA, those options may be more compelling.

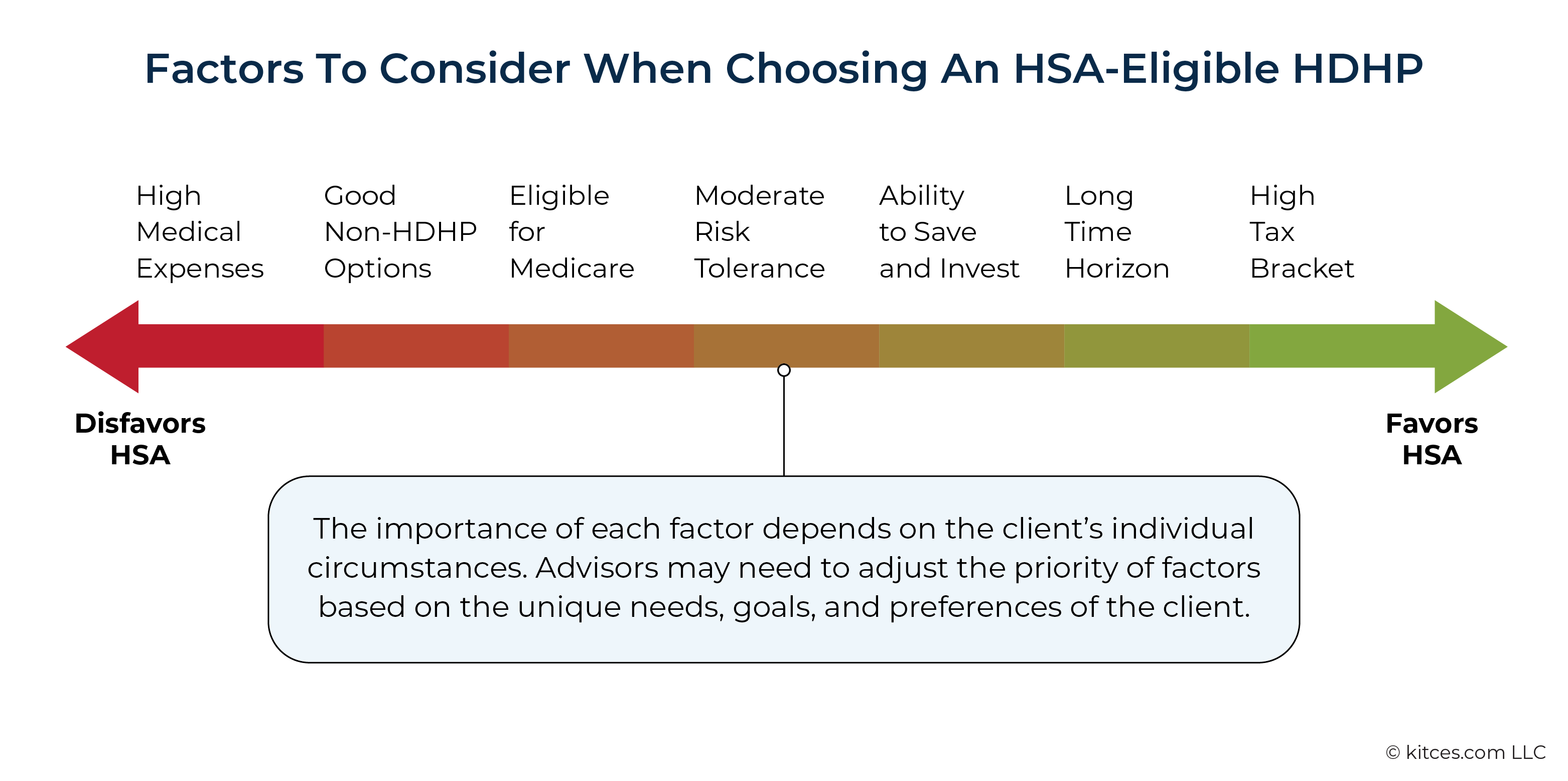

While every situation is unique, several factors can influence the suitability of choosing an HSA-eligible health plan. For instance, factors like high medical expenses or access to good non-HDHP options are typically more likely to disfavor an HSA, as these can reduce the benefits of the plan's high-deductible structure. On the other hand, characteristics such as having a long investment time horizon, being in a high tax bracket, or having the ability to save and invest tend to make HSAs more advantageous, given their triple-tax benefits and potential for long-term growth.

The graphic below illustrates how these factors might fall across a spectrum, which can help advisors and clients visualize how different circumstances might weigh in the decision-making process.

No single factor will be decisive. However, by considering the totality of a client's personal and financial circumstances, advisors can help clients make informed decisions about their healthcare and savings as they contemplate their financial future, balancing short-term considerations with long-term planning!