Executive Summary

In today’s contentious legislative environment in Washington, it’s not often that Congress passes any legislation. Which means when a bill actually is on track to be approved, various members of Congress often tack on a number of other provisions that they wish to see approved as well (either individually, or as part of the negotiated process for a compromise to pass the overall legislation).

Thus was the path of the recent Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (H.R. 1892), which was passed into law by President Trump on Friday, February 9th. As while it was intended primarily as the legislation that would avoid a government shutdown by agreeing to increase government spending limits and raising the debt ceiling for two years, buried in the legislation were a number of tax-related provisions – some temporary, and others permanent – with impact for both high-income and low-income households.

Of primary note for financial advisors who work with higher-income individuals is that, starting in 2019, there will be a new IRMAA tier for Medicare Part B premium surcharges for individuals earning more than $500,000 (or married couples with AGI in excess of $750,000), stacked on top of what were additional adjustments to the Medicare premium surcharge tiers that just took effect in 2018 as well!

Also included in the legislation were a number of temporary-but-immediate retroactive reinstatements of popular tax provisions for 2017, including the above-the-line education deduction (for those who weren’t already fully eligible for the American Opportunity or Lifetime Learning Tax Credits), the deductibility of mortgage insurance premiums, and relief from any cancellation-of-debt income for those who go through a short sale with an underwater mortgage on their primary residence.

In addition, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 also provides a number of changes to grant more flexibility for hardship distributions from employer retirement plans, authorizes the creation of a new Form 1040SR (an “E-Z” tax filing form for seniors), and provides a number of retirement-plan-related and other tax relief provisions for those who were impacted by the California wildfires in late 2017!

Which means even though the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 was nominally “budget legislation” and not a tax law, a number of households may be impacted by its tax-related changes!

New Top Tier For Medicare Part B IRMAA Surcharges

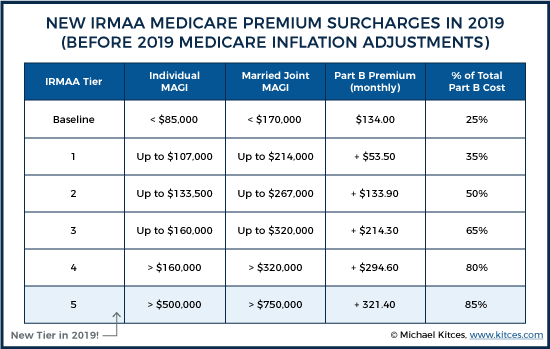

Since 2006, the Medicare Modernization Act has required that certain “high-income” individuals pay an Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (IRMAA) as a surcharge on their Medicare Part B premiums. In 2018, the surcharge starts at an extra $53.50/month, can rise as high as an extra $294.60/month on Medicare Part B, and applies to those whose (Modified) Adjusted Gross Income exceeds $85,000 (for individuals, or a MAGI above $170,000 for married couples). The end result of these IRMAA surcharges are to increase the total percentage of Part B costs that are covered by premiums, from 25% (the amount covered by the base $134/month Medicare Part B premium) to as high as 80% (for those paying the full $134 + $294.60 = $428.60/month premium).

Under the new Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, though, a new additional tier of surcharges is being introduced for 2019, at a MAGI threshold of $500,000 for individuals (or $750,000 for married couples). Notably, the threshold for married couples is “only” 150% of the threshold for individuals, introducing an aspect of “marriage penalty” for high-income couples on Medicare. The new tier is intended to lift the Part B premium coverage from 80% to 85% for those high-income earners on Medicare.

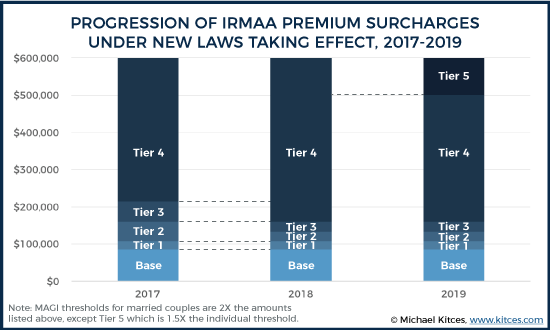

It’s also important to note that the new IRMAA tier for 2019 stacks on top of the changes to IRMAA tiers that just took effect in 2018 as a part of the Medicare Access And CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, which had already reduced the top IRMAA tier (where the 80%-of-costs threshold kicks in) from $214,000 in 2017 to only $160,000 in 2018 (thresholds doubled for married couples). Thus, in the span of two years, the depth of the top IRMAA tiers has been expanded rapidly, while the bottom three IRMAA tiers have become compressed – albeit still with an individual threshold of $85,000 for individuals (or $170,000 for married couples), which means it only applies to a limited number of households in the first place.

Individual Tax Breaks Retroactively Reinstated For 2017

For much of the past decade, a handful of individual tax incentives have been regularly subject to a series of short-term extensions… after which they would lapse, until/unless reinstated and extended again… which in practice happened so often they literally became known as the “Tax Extenders”.

In the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act of 2015, a number of popular Tax Extenders became permanent, including Qualified Charitable Distributions from IRAs, the deduction for State and Local Sales Taxes (albeit now subject to the overall $10,000 SALT deduction cap from TCJA 2017), and the American Opportunity Tax Credit that replaced the “old” Hope Scholarship Credit back in 2009.

However, a handful of popular individual tax breaks did not get made permanent under the PATH Act, and instead were only extended “temporarily” for 2 years, through the end of 2016, and lapsed as of December 31st of that year. Accordingly, the Bipartisan Budget Act has reinstated those provisions, retroactively, for the 2017 tax year, including the above-the-line deduction for tuition and fees, the deductibility of mortgage insurance premiums, and the ability to exclude discharged primary residence mortgage debt from income.

Above The Line Education Deduction For Tuition And Fees Reinstated For 2017

The above-the-line education deduction for tuition and fees allows taxpayers to deduct up to $4,000 of tuition and enrollment fees for college for themselves or their dependents. Any expenses claimed for the Tuition and Fees deduction cannot have been paid from a(n already-tax-favored) 529 college savings plan, a Coverdell Education Savings Account, or via tax-free interest from a savings bond.

The Tuition and Fees deduction is partially phased out (from a $4,000 maximum down to only $2,000) for individuals with (modified) Adjusted Gross Income above $65,000 for individuals (or $130,000 for married couples), and is completely phased out once income exceeds $80,000 for individuals (or $160,000 for married couples).

Notably, the Tuition and Fees deduction also cannot be claimed on behalf of any student who already claimed the American Opportunity Tax Credit (or Lifetime Learning Credit) in the same tax year. And since the American Opportunity Tax Credit is actually a dollar-for-dollar credit for the first $2,000 of expenses (and 25 cents on the dollar for the next $2,000), it is always better to claim the AOTC where available (generally, the first four years of college), especially since it has higher income phaseout limits anyway.

Thus, in practice, the reinstatement of the Tuition and Fees deduction will be primarily beneficial for:

- Students who are beyond their first four years of undergrad education (or in graduate school);

- Students/families with income above $56,000 (filing as individuals, or $112,000 for married couples) but under $80,000 (and $160,000, respectively), where the Lifetime Learning Credit will be phasing out faster than the Tuition and Fees deduction; and

- Families with multiple students beyond the first four years of college, where the Lifetime Learning Credit can only be claimed once per tax return (i.e., per family with multiple students), while the Tuition and Fees deduction can be claimed across multiple students (as long as the family remains below the income phaseout threshold)

However, the reinstatement of the Tuition and Fees Deduction is only for the 2017 tax year, and has already implicitly re-expired at the end of 2017, which means it is not currently available for the 2018 tax year. In addition, because the Tuition and Fees Deduction was just reinstated, retroactively, for 2017 as of February 9th of 2018, some tax reporting software may not yet be updated for the (retroactive) change for 2017 tax filings. (Though fortunately on Form 1040 for 2017, it appears it can still be claimed on Line 34 where it was previously claimed, albeit on a line that is currently marked as “Reserved For Future Use”!)

Deductibility Of Mortgage Insurance Premiums Reinstated For 2017

Under IRC Section 163(h), mortgage interest is deductible as an itemized deduction, and since 2007 the tax law has also permitted those who pay mortgage insurance premiums (e.g., Private Mortgage Insurance [PMI] on a mortgage that had a less-than-20% downpayment) to deduct them as mortgage “interest” as well. The deduction began to phase out once Adjusted Gross Income exceeded $100,000 (for individuals and married couples), and fully phased out by $110,000 of AGI.

This deduction for mortgage insurance premiums was one of the tax extenders that was repeatedly extended, lapsed, extended again, and lapsed again, over the span of a decade, and had last been extended under the PATH Act through the end of 2016.

With the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, the mortgage insurance premium deduction is retroactively reinstated for 2017 – which means those who had already paid mortgage insurance premiums will simply find they can deduct them on the 2017 tax return, as a part of their “mortgage interest” deduction (on Line 13 of Schedule A, where a placeholder for the mortgage insurance premium deduction was retained).

Notably, the reinstatement for deducting mortgage insurance premiums has no relationship to the new rules limiting mortgage interest deductibility (including the elimination of deductions for home equity indebtedness) under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, as those rules only apply for the 2018 tax years and beyond (while the mortgage insurance premium deduction is only reinstated retroactively for 2017).

Exclusion Of Discharged Principal Residence Mortgage Debt For 2017 Short Sales

Under IRC Section 108, the partial or total cancellation of an outstanding debt balance (not pursuant to a formal bankruptcy) is treated as income to the recipient – akin to receiving a (taxable) gift of cash that was used to repay the debt. Thus, for instance, a lender who agrees to forgive a borrower’s $10,000 debt compels the borrower to report $10,000 in income for the amount forgiven; and in the case of an “underwater” mortgage (e.g., a $300,000 mortgage on a $250,000 property), the excess $50,000 of debt that is discharged in a short sale (where the property is sold in total satisfaction for the debt) is similarly treated as “Cancellation Of Indebtedness Income” (CODI).

However, the national decline in real estate that began in 2007 (and was accelerated by the financial crisis) threatened to trigger cancellation-of-debt income on a mass scale, as houses were foreclosed upon in short sales across the country. To provide some relief for the situation, the Mortgage Debt Relief Act of 2007 changed the standard CODI rules by providing that up to $2,000,000 of canceled debt associated with the mortgage on a primary residence could be discharged without tax consequences.

Unfortunately, though, the original law was temporary, and expired and got reinstated and extended several times since 2007, most recently through the end of 2016 under the PATH Act of 2015.

And now the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 has now retroactively reinstated it again for (just) the 2017 tax year.

In practice, this simply means that any homeowners who liquidated their primary residence (and it must be a primary residence) in an underwater-mortgage short sale in 2017 will not have to report the cancellation-of-indebtedness income that might have otherwise been due. Since the 2017 tax year is already closed, there’s no way to sell for the 2017 tax year if the transaction hasn’t already occurred, and as it currently stands the provision has once again lapsed for 2018 (and may or may not be reinstated and extended again).

Greater Flexibility For 401(k) Hardship Distributions

Most 401(k) plans limit the ability of employees to take “in-service” distributions, limiting their ability to access the money until they actually retire (or at least, separate from service), or via a 401(k) loan option.

However, some employer retirement plans also allow employees to take a so-called “hardship distribution”, where the employee can take a distribution that is not a loan (i.e., does not need to be repaid, and in fact cannot be repaid) and without separating from service, in situations of “immediate and heavy financial need” (e.g., sudden medical expenses, burial/funeral expenses for a family member, or even certain costs related to the purchase of a primary residence or for college costs, which must be substantiated to the plan administrator). Hardship distributions are taxable to the recipient (as with any other distribution from an employer retirement plan), though, and the early withdrawal penalty may also apply (unless an exception is otherwise available).

To limit potential abuse of hardship distributions, employer retirement plans are permitted to decide whether to even offer such distributions, and have some latitude to define what “immediate and heavy financial needs” will be eligible under their plan. In addition, hardship distributions can generally only be made from prior salary deferrals contributed to the plan (i.e., the $18,500/year contribution limit) but not the growth on those deferrals, or from employer profit-sharing or matching contributions. In addition, some employer retirement plans will only allow hardship distributions after the maximum available 401(k) loan amount has been taken, and may suspend new contributions for up to 6 months after a hardship distribution occurs.

Under the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, though, the 6-month prohibition on contributions after a hardship distribution is repealed (starting in 2019), the requirement to take available loans before a hardship distribution is also repealed (starting in 2019), and going forward a hardship distribution can draw upon salary deferrals, profit-sharing contributions, matching contributions, and all growth/earnings from any of those categories (again starting in 2019).

Notably, though, the additional flexibility for hardship distributions will not be automatic; instead, it’s still up to the employer to update and amend the plan for 2019 to allow for the more flexible options, and the employer is free to decide not to permit greater (or any) hardship distribution flexibility at all.

California Wildfire Relief, A New Form 1040SR, And Other Miscellaneous Provisions

Ultimately, as noted earlier, the core focus of the Bipartisan Budget Act was to resolve the government debt ceiling, and approve key budget provisions for major Federal agencies… not to pass new tax laws. However, the reality is that whenever a major law is actually passing through Congress – which doesn’t happen very often – it’s not uncommon for a large number of other “miscellaneous” provisions to get attached along the way, which may have tax planning implications.

Some other notable provisions of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 include:

- New Form 1040SR. The IRS is directed to create a new Form 1040SR, which is intended to provide another simplified and expedited tax filing process (akin to Form 1040EZ), but specifically for Seniors who are age 65 or older, who may need to also report Social Security benefits, pensions, and retirement account distributions (which are not otherwise included on Form 1040EZ).

- Ability To Rollover Improper Levies Back To An IRA. In rare instances, the IRS finds it necessary to levy an individuals retirement account directly to collect taxes that are due, and in some situations, it turns out that the levy was unnecessary (as the taxpayer ends out paying by other means). In such situations, though, the IRA funds, once withdrawn, were typically unable to be rolled over (as the 60-day rollover period would often long since have passed). To provide relief, BBA 2018 allows individuals who had a “wrongful or improper levy” against their IRA to roll the money back into the IRA (including from an inherited IRA).

- Disaster Relief For Those Impacted By California Wildfires. In light of the horrible California wildfires that struck in late 2017, the Bipartisan Budget Act provides a number of retirement-plan-related and other relief provisions for those who were impacted (i.e., those whose principal place of residence from October 8th to December 31st of 2017 was in the Federal wildfire disaster area), including: the ability to recontribute any retirement plan withdrawals that were taken to purchase a residence where the purchase was cancelled due to the wildfires; an increase in the 401(k) loan limits to $100,000 (or the full amount of the vested account balance) for the rest of 2018 for anyone who suffered an economic loss (with the ability to delay loan repayments for a year); the ability to take an outright withdrawal of up to $100,000 from an IRA without an early withdrawal penalty (albeit still subject to normal income taxes, but able to be spread out over 3 tax years); the opportunity to claim the earned income or child tax credits based on prior-year earned income (instead of current-year earned income) if current-year (2017) income was lower; and increased casualty loss limits for those impacted by the wildfires (removal of the 10%-of-AGI threshold, and ability to deduct even for those who don’t itemize).

In the end, the Bipartisan Budget Act was not intended to be “tax legislation” first and foremost, and to the extent that any tax provisions were included, most were temporary (from the reinstatement of various 2017 tax breaks, to disaster relief for the California wildfires). Nonetheless, some provisions – such as the new IRMAA tier for high-income taxpayers – are permanent, and will remain relevant for many years to come!

So what do you think? Do you have any clients who will be impacted by the provisions of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!