Executive Summary

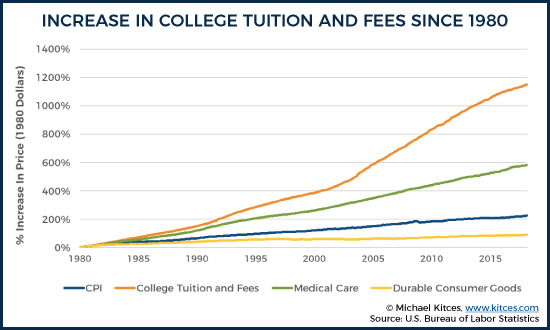

The “traditional” view of recent decades is that going to college is part of the American Dream, and the essential pathway to better job opportunities with higher income potential. Yet at the same time, there's growing talk of the financial hardships for students these days, from ever-increasing tuition, to high levels of student debt. Still, under the auspices that a college education is essential to unlocking future income opportunities, students continue to enroll in record numbers. Which raises the question: is college really still a good "investment", or not?

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – examines recent research on the Return On Investment (ROI) from investing in a college education, and particularly the differences in ROI that students may experience based on their own abilities as students, along with their area of study, the type of institution they attend, and the funding that is available to them.

Notably, while the "traditional" view is that a college education is all about building knowledge and developing skills (the "human capital" theory of education), in his 2018 book, The Case Against Education, economist Bryan Caplan examines prior research on education and concludes that the primary function of higher education is actually just to signal certain traits of students to prospective employers – particularly intelligence, work ethic, and conformity (known as the "signaling" theory of education). But setting aside the debate over whether education is primarily a means of developing human capital or signaling (which has some important implications for social returns to investment in education), Caplan's book contains what might be the most detailed analysis of private returns to investment in education (i.e., the ROI of a college degree for individuals), which is highly relevant to any financial planner who advises clients (or their children, or grandchildren) on whether it's really still worth trying to invest in a college education in the modern era.

Because while the data is fairly clear that those who go to college do tend to have higher incomes in their working careers, simplistic methods for calculating the ROI from investing in a college education often suffer from "selection bias", which refers to the fact that those who choose to go to college are not selected at random. For instance, on average, those who choose to go to college tend be more intelligent and harder working than those who do not (a result of the college admissions screening process). Of course, this certainly isn't true of everyone who does not go to college, but because it's true on average, we would expect those who go to college to (on average) earn more in the labor market, regardless of whether college actually improved their skills or knowledge, simply because of the intelligence and work ethic they brought with them to college to begin with. Thus, it is important to correct for this "ability bias" when determining the ROI of a college education; Caplan's calculations, though, go much further than that, adjusting for a wide range of other factors that are often overlooked – from health and happiness, to the probability of unemployment, and even college boredom (or lack thereof).

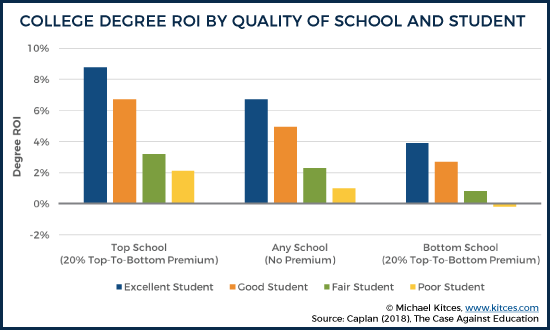

With this framework in place, Caplan then determines the ROI of a college education across a wide range of scenarios, including student quality (e.g., an excellent student vs. a poor student), type of degree (e.g., Bachelor's vs. Master's), a student's area of study (e.g., engineering vs. fine arts), college quality (e.g., top-tier vs. bottom-tier), and institution type (e.g., public vs. private). In short, Caplan finds that college is a good investment for good students, a mediocre investment for mediocre students, and a bad investment for bad students, who are especially prone to paying for some of college and then not even finishing (incurring the cost/debt but not even getting the signaling benefit of the degree). Beyond that, only the best students should pursue a Master's degree, field of study does matter (though more so for low-quality students), college prestige has a potentially surprisingly small impact, and the best investments are generally found at the top public university where an individual is eligible for in-state tuition (not a leading private college).

Ultimately, Caplan's analysis has many important considerations for those who may help students choose what type of education to pursue... from not pushing students who are a poor fit to attend college (as this is often the worst case scenario from an ROI perspective, where students may take on all of the expense of a college education yet gain none of the benefits), to helping students who are a strong fit to decide what path makes the most financial sense (and Caplan even makes his spreadsheets publicly available, incase anyone wants to tweak his model to better fit their situation). But the key point is to acknowledge that the ROI of a college investment varies greatly based on the characteristics of a student - primarily by amplifying the positive results for good students, while mostly amplifying the downside risk for bad students - and many other factors that are often overlooked. College may be a great investment for some, but it is not for all!

The Value Of Investing In A College Education: Human Capital vs. Signaling

Among economists, there are two broad theories for why individuals invest in a college education.

The first—the human capital model—provides the perspective that is intuitive to most: We go to college to build valuable skills and knowledge. These skills and knowledge then make us more productive (increasing the economic value of our work), and, therefore, enable us to earn more in the labor market. As a result, even with the rapidly-rising cost of college (well above the general level of inflation), it's worth "investing" in a college education to gain the additional knowledge and skills that unlock higher-income job potential.

Yet not everyone is convinced that the value of a college education is just—or even primarily—about gaining knowledge and skills which increase our earning potential. The second broad theory of why we go to college—the signaling model—suggests that rather than being a way to build skills and knowledge, higher education serves as a means for those with traits that are rewarded in the labor market (intelligence, work ethic, conformity, etc.) to signal to prospective employers that they have such traits in the first place. In other words, college isn’t about developing skills and knowledge, but simply a means for those with positive traits such as intelligence and work ethic to demonstrate their capabilities in a credible way.

The signaling model is compelling because an unfortunate reality of making hiring decisions is that there's a high degree of asymmetric information between a prospective employer and an applicant. The applicant knows much more about their true skills and ability than the prospective employer, yet the employer can’t rely on the applicant’s self-assessment, as the applicant is highly conflicted. After all, regardless of their true skills and ability, applicants are going to portray themselves in as positive of a light as possible.

In situations where there is a high degree of asymmetric information, "signaling" can be one way in which parties can credibly convey information to one another. There are a few key elements to sending credible signals. First, signals must have some cost associated with sending them. If a desirable signal were not costly to send, then everyone would send it, and the signal would not convey any meaningful information. Additionally, signals must be relatively less costly to send for those who possess the trait(s) being signaled, therefore increasing the likelihood that someone signaling a particular trait actually has that trait.

This is why “talk is cheap”. Anyone can say they are punctual, so merely saying so doesn’t convey any credible information. But when a job candidate shows up 15 minutes early for their interview, they are conveying something more credible than what can be expressed in their own words. Of course, signals aren’t perfect. The “cost” of showing up 15 minutes early to one interview is relatively trivial. Even someone who isn’t normally punctual can manage to make it to a single interview early. Additionally, even candidates who generally are punctual can get delayed for circumstances that are entirely out of their control. Nonetheless, all else being equal, we’re skeptical of the candidate who claims to be punctual yet shows up late, and a bit more confident in the true punctuality of the candidate who shows up early.

When it comes to college education, attending college as a signal to prospective employers “works” because it is difficult and costly—in terms of both time and money—to complete a college degree, which means those who do complete their degree (possibly sorted further by grades) are able to signal these positive traits, regardless of any actual skills or knowledge gained.

Notably, this theory addresses many questions commonly posed about higher education. Why make students spend four years working towards a degree, rather than just administer a test and certify who’s the most intelligent? Why do students study subjects that have nothing to do with their future occupations? Why make students jump through a bunch of arbitrary and bureaucratic hoops, in order to fulfill their degree requirements?

The answer, to oversimplify a bit, is that education signals a bundle of traits, in particular intelligence, work ethic, and conformity. Few employers are interested in a genius with no work ethic. Similarly, few jobs in a modern economy are all brawn and no brains. And in either case, employers generally don’t want employees who are unwilling to put up with some bureaucracy and follow instructions from superiors when needed (i.e., to reasonably conform to the demands of the workplace). Since successfully making it through four years of college (particularly with high marks) requires a mixture of intelligence, persistent effort, and willingness to do some things just because you are told to do so, education is a potentially great mechanism for signaling to employers. And since going to college is costly in terms of both time and effort, though less costly for those who exhibit traits that are attractive to employers, education fulfills the requirements for sending an effective signal.

Private vs. Social Benefits Of Going To College

Notably, the debate among economists over whether the human capital model or the signaling model of education better describes reality has important implications for the social returns of higher education, but not the private returns for any one individual.

If higher education does build genuine skills and knowledge, then society as a whole may experience benefits of a more skilled and educated populace, which means the benefits of college extend beyond just the individual to provide a net social return as well.

However, if education is mostly a form of signaling, then having students spend 4+ years of their life merely demonstrating their fitness for the labor market may be inefficient, both in terms of the cost to students and the cost to society (given the cost of both taking so many young and productive workers out of the workforce as well as the public funds to go towards higher education).

As economist Bryan Caplan examines in-depth in his 2018 book, The Case Against Education, there is a considerable amount of evidence which suggests that a college education is largely a means of signaling rather than a means for building skills and knowledge.

As economist Bryan Caplan examines in-depth in his 2018 book, The Case Against Education, there is a considerable amount of evidence which suggests that a college education is largely a means of signaling rather than a means for building skills and knowledge.

For instance, the “sheepskin effect” (named after the parchment on which degrees were traditionally printed) refers to the fact that completion of the last semester needed to graduate earns a much higher premium than all other semesters, which would not be expected if students were developing additional skills and knowledge each semester. Additionally, college graduates out-earn non-graduates in fields that have nothing to do with their education (e.g., waiting tables), which would also not be expected if education helped build skills and knowledge rather than just signal them. And, of course, there’s student behavior itself—particularly the fact that students tend to pursue “easy A’s” and celebrate canceled class, both of which would not be expected if this meant that students were losing out on the development of valuable skills and knowledge that could be applied in the future.

Caplan ultimately concludes that much of higher education is a wasteful form of signaling, and this consideration is the main topic of his book (hence the title). But setting aside the contentious issue of the social value of education, Chapter 5 of Caplan’s book, “Who Cares If It’s Signaling? The Selfish Return to Education”, provides an excellent in-depth analysis of the private Return on Investment (ROI) for an individual investing in a college education, which is highly relevant to any financial planner who advises clients (or their children, or grandchildren) on going to college.

The ROI from Investing in a College Education

Determining the true ROI from investing in a college education is actually more difficult than it may seem at first. While many people attempt to make simple calculations based on merely calculating the Internal Rate Of Return (IRR) that results from comparing the cash flows (both college expenses and future earnings) of a typical college graduate to those of a typical non-graduate (or between fields, types of schools, etc.), the reality is that both those who go to college, and those who do not, are not selected at random.

On average, those who go to college tend to be more intelligent and hard-working than those who do not. Of course, this is only true on average, and there are many without college degrees who are more intelligent and harder working than those who go to college, but because the general trend does exist (and in fact colleges screen for it with an application process focused on high school grades and standardized tests like the SATs and ACTs), it is likely that many college graduates would have outearned their non-college graduate peers regardless of whether they went to college!

Simply comparing those who went to college versus those who did not is subject to significant “selection bias”. And because those who are more intelligent and harder working are more likely to go to college (again, on average), this ability bias must be accounted for when determining the ROI of a college investment. However, many simplistic calculations of the prospective ROI of a college education fail to make this adjustment.

Yet as Caplan notes, there are many other limitations to most simplistic calculations as well. After adjusting for a large number of factors that are often overlooked (e.g., unemployment, taxes, government transfers, job satisfaction, happiness, and even factors such as the differing levels of satisfaction that students get from attending classes), Caplan reaches the conclusion that college is a good investment for good students, a mediocre investment for mediocre students, and a bad investment for bad students.

ROI By Student Quality

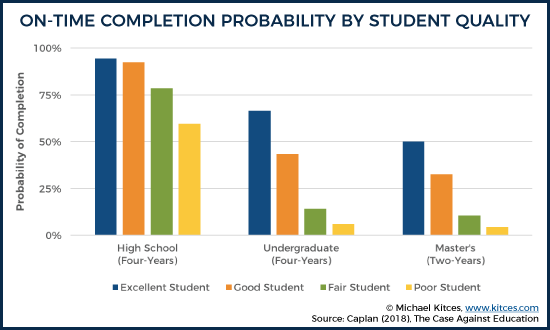

Much of the difference in ROI is due to varying completion percentages of students of different ability. For instance, though low-quality students may experience similar increases in earnings as high-quality students (at least until a worker’s true attributes can be revealed through experience in the workforce), low-quality students fail to graduate at a much higher rate than high-quality students. And notably, since almost all of the return from investing in college education comes at graduation (i.e., the sheepskin effect), the absolute worst thing a student can do is incur the cost of going to college (in both time and money) and yet fail to finish college and earn a degree.

In order to quantify how big of a difference student quality can make, Caplan examines four hypothetical student archetypes of varying quality: “excellent” students (which correspond to students with the typical traits of an individual who completes a master’s degree); “good” students (which correspond to students with the typical traits of an individual who completes a bachelor’s degree); “fair” students (which correspond to students with the typical traits of an individual who completes high school); and “poor” students (which correspond to students with the typical traits of an individual who does not complete high school). Based on these profiles, Caplan estimates that an excellent student would be at about the 82nd percentile of cognitive ability, whereas a poor-quality student would be at about the 24th percentile.

Notably, even four-year completion rates of excellent students can be much lower than are commonly realized. Though excellent students are almost certain to graduate from high school, they only have about a 65% chance of completing their bachelor’s degree. However, things look much worse for the poor student, who only has about a 60% chance of completing their high school education in four years, and a 10% chance of completing their bachelor’s degree in the same amount of time.

In summarizing his findings, Caplan says:

Results closely match common sense. High school is lucrative for all four archetypes. Even Poor Students can reasonably expect the resources they invest in high school to out-perform high-yield bonds. College, in contrast, is a solid deal only for Excellent and Good Students. Largely owing to their high failure rates, Fair Students who start college should foresee a low 2.3% return on their investment. For Poor Students, it’s a paltry 1%. Master’s degrees, finally, are a so-so deal for Excellent Students, a bad deal for Good Students, and a money pit for Fair and Poor Students.

ROI By Major

Not surprisingly, not all college degrees are created equal. Some majors pay better than others, and many additional factors—including the quality and prestige of an institution, whether a student receives financial aid or pays in-state tuition, and even the length of time that it takes a student to complete a degree—influence the ROI of a college education. Caplan examines many of these factors in his book (too many to cover here), but a few, in particular, stand out.

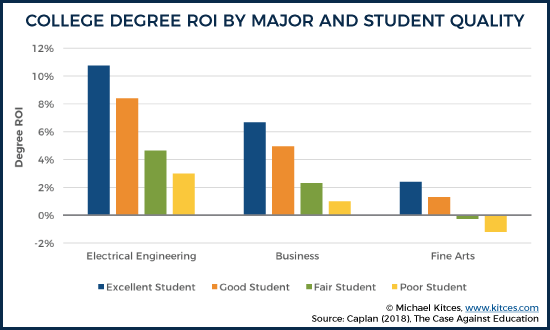

First, the topic a student chooses to study matters. Caplan examines three different majors with differing earnings prospects: electrical engineering, business, and fine arts. As most would expect, the ROI is highest for electrical engineering and lowest for fine arts.

However, Caplan’s analysis teases out some more nuanced relationships between major and student quality. For instance, high-quality students have much greater flexibility in terms of their field of study. Though electrical engineering provides a higher ROI than the fine arts regardless of student quality, an excellent student in the fine arts may earn an ROI that is only slightly lower than the ROI of a poor student in electrical engineering.

It is also important to acknowledge what a 0% return means in this context. As Caplan notes:

Zero and negative returns don’t mean fine arts degrees are worthless in the labor market. A fine art degree raises expected income over 20%. What zero and negative returns mean, rather, is that capturing that raise is more trouble for Fair and Poor Students than it’s worth.

Which means that fine arts degree truly can be worthwhile investments, particularly once considering an individual’s specific preferences for a given career. Though an excellent student could likely earn more studying electrical engineering rather than fine arts, fine arts may be the best option for a student who loves the arts and would be miserable in an engineering career (especially since not completing the degree at all is ultimately the “worst” outcome, far worse than just having the “wrong” major). And in any case, a college education is still likely to be worth the time and effort for an excellent student. It’s lower quality students who must be most careful about what field of study they pursue—particularly if they are interested in a field that is lacking in practical value.

ROI By College Quality

Another important factor to consider is the quality of an educational institution. Caplan notes that past research is mixed on how much (if any) premium is earned for attending a higher quality school. Of course, Harvard graduates do earn more than graduates of most public universities, but just as “ability bias” must be accounted for when comparing those who go to college with those who do not, ability bias is present when comparing students who go to Harvard with those who go to a typical public university, as Harvard is more selective for those with high levels of ability.

Because it’s hard to sort out ability bias, estimates of the value of attending a more prestigious school tend to vary. Caplan provides ROI calculations ranging from the low estimate of no quality premium (i.e., all of the earning differences between Harvard grads and those of State University are due to ability bias), to a high estimate of about a 20% premium when comparing “bottom” schools to “top” schools (i.e., attending a top-tier school versus a bottom-tier school boosts one's earning potential by 20% beyond the differences that can be attributed to student ability).

As the chart above indicates, the more quality premium that is assumed, the more it becomes important for students to get into higher quality schools. But because it is hard to definitively say whether any premium exists, it is therefore impossible to say what conclusions prospective students should take from this information. If there is no premium after accounting for ability bias, then it really doesn’t matter what school a student goes to. But if there is “free lunch” quality premium above and beyond the effects of ability bias, then students should aim as high as they can.

However, there may be some good reasons to be skeptical of earning higher returns merely due to going to a more prestigious school. For instance, Caplan notes a 2014 study by Dale and Krueger which found that students who submit many applications to top schools have better career success regardless of whether or not they actually attend a top school. This can be seen as evidence against a large quality premium, as it suggests that the hard-to-observe characteristics revealed by such behavior (persistence, forethought, etc.) may actually be what’s driving higher earnings later in life. In other words, if a student is conscientious enough to plan for the future and go through the process of submitting a number of applications to top schools, then they are likely the type of student who will be successful regardless of what school they go to.

Nonetheless, there may be some good reasons for students to prioritize prestige, particularly in light of their specific career aspirations. There are some careers or areas of graduate study (e.g., investment banking, elite law or medical schools, and some research positions) where institutional prestige may make a bigger difference than others. However, students should also be mindful of the fact that the competition among peers is more difficult at prestigious schools. A good student may have better odds of successfully completing an engineering degree at State University rather than MIT. And, in any case, if a student hopes to ultimately work in a fairly standard engineering role, it’s not clear that being a merely good student at MIT (which would likely place a student in the bottom half of their class) would result in any better career prospects than what a good student would have when graduating from State University (where they may be in the top half of their engineering class).

ROI By Type of Institution

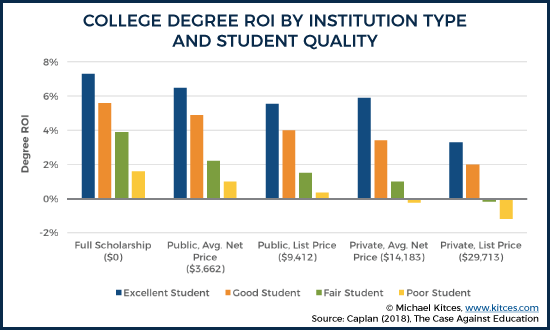

Of course, another crucial factor in order to determine the ROI of a college education is how much that education costs, and those costs can vary substantially based on the type of institution. At one end of the spectrum, a student with a full scholarship pays nothing to attend college (although they would still incur an opportunity cost of their foregone earnings over these years). At the other end of the spectrum, paying list price at a private university can easily cost well over $100,000 over the course of four years.

To examine the ROI across various institution types, Caplan also calculates the ROI of a college education based on both listed and average net prices of tuition and fees (but not housing, as housing costs exist whether a student goes to college or not) at public and private institutions.

Not surprisingly, the best ROI generally comes from receiving a full scholarship. After that, public institutions generally provide higher ROIs relative to private universities. In fact, Caplan notes that “as long as your state’s best public school admits you, there’s no solid reason to pay more.” Lower quality students should be particularly wary of private institutions from an ROI perspective (assuming they don’t receive a full scholarship), given both the outright cost and the higher impact of that cost if the student doesn’t actually finish their degree.

However, one notable caveat to these considerations is that many of the most elite colleges provide generous financial support to families with financial need. As Caplan notes, “Excellent Students from poor families are well advised to apply to top schools—and go with the lowest bidder.”

Tying It All Together

Fortunately, Caplan is very generous in providing all of the spreadsheets underlying his calculations for determining the ROI of going to college. If you disagree with any of his assumptions, want to add something else to his models, or simply want to dig deeper into his actual model, you can easily do so with his spreadsheets.

In summarizing his thoughts after calculating the ROI of a college education many different ways, Caplan concludes by saying:

The clearest lesson: dropping out of high school is imprudent for virtually all shapes and sizes. Even Poor Students who loathe school should foresee returns near 5%. Other lessons: Higher education is a good deal for Excellent Students even if they despise school. For Good Students, though, deep-seated hostility makes higher education a close call. The flip side: College is a so-so deal for Fair students who truly love school. Otherwise, higher education for Fair and Poor students is a hail-Mary pass. Unless they get lucky, they can better prepare for their future by getting a job and saving money. The master’s degree, finally, is an okay deal for Excellent Students who adore school. Everyone else, beware.

Personally, my biggest concern with Caplan’s model is his assumption of constant earnings growth of 2.5% across all scenarios. Because earnings growth rates are much higher among the highest earners than they are among the lowest, I suspect Caplan’s calculations understate earnings growth for the highest quality students and overstate earnings growth for the lowest quality students. If that is correct, the dispersion between the ROIs of the highest quality and the lowest quality students would be even larger than Caplan suggests, which means that college would generally be an even better investment for excellent students but a worse investment for poor students.

Parents and educators should also note the implications of Caplan’s research when encouraging students to pursue higher education. While it is a great investment for many students, it’s not a great investment for all students. Particularly for students who have historically struggled with school, if nothing about their situation or circumstances has changed (e.g., the student still is not interested or motivated to try in school), then encouraging or pressuring a student to go to school could actually do great financial harm to them, as they are the students most likely to end up with the worst ROI (i.e., pay for several years of education and yet receive no degree that actually boosts their earnings potential).

Such students may want to instead consider many of the excellent career opportunities available through trade and vocational programs. If a student suddenly picks up an interest in continuing their education, then transfer options to public universities are often available. And, if not, students will at least develop real-world skills that can help them earn a great living (and, in many cases, pay better than the jobs comparable peers will have coming out of four-year programs...with or without a degree).

But ultimately, the key point is to acknowledge that the ROI of a college investment varies greatly based on the characteristics of a student, their field of study, their institution, and how they pay for college. College is a great investment for some, but not for all!

So what do you think? Is it appropriate to recognize that the value of a college education may itself depend on how good of a student the individual is in the first place? Do you think a college education is primarily about building knowledge and developing skills, or just to signal other favorable workplace traits? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply