Executive Summary

The annual requirement of all Americans to pay taxes on their income requires first calculating what their “income” is in the first place. In the context of businesses, the equation of “revenue minus expenses” is fairly straightforward, but for individuals – who are not allowed to deduct “personal” expenses – the process of determining what is, and is not, a deductible expense is more complex.

Fortunately, the basic principle that income should be reduced by expenses associated with that income continues to hold true, and is codified in the form of Internal Revenue Code Section 212, that permits individuals to deduct any expenses associated with the production of income, or the management of such property – including fees for investment advice.

However, the recent Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 eliminated the ability of individuals to deduct Section 212 expenses, as a part of “temporarily” suspending all miscellaneous itemized deductions through 2025. Even though the reality is that investment expenses subtracted directly from an investment holding – such as the expense ratio of a mutual fund or ETF – remain implicitly a pre-tax payment (as it’s subtracted directly from income before the remainder is distributed to shareholders in the first place).

The end result is that under current law, payments to advisors who are compensated via commissions can be made on a pre-tax basis, but paying advisory fees to advisors are not tax deductible… which is especially awkward and ironic given the current legislative and regulatory push towards more fee-based advice!

Fortunately, to the extent this is an “unintended consequence” of the TCJA legislation – in which Section 212 deductions for advisory fees were simply caught up amidst dozens of other miscellaneous itemized deductions that were suspended – it’s possible that Congress will ultimately intervene to restore the deduction (and more generally, to restore parity between commission- and fee-based compensation models for advisors).

In the meantime, though, some advisors may even consider switching clients to commission-based accounts for more favorable tax treatment, and larger firms may want to explore institutionalizing their investment models and strategies into a proprietary mutual fund or ETF to preserve pre-tax treatment for clients (by collecting the firm’s advisory fee on a pre-tax basis via the expense ratio of the fund, rather than billed to clients directly). And at a minimum, advisory firms will likely want to maximize billing traditional IRA advisory fees directly to those accounts, where feasible, as a payment from an IRA (or other traditional employer retirement plan) is implicitly “tax-deductible” when it is made from a pre-tax account in the first place.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that, while unintended, the tax treatment of advisory fees is now substantially different than it is for advisors compensated via commissions. And while some workarounds do remain, at least in limited situations, the irony is that tax planning for advisory fees has itself become a compelling tax planning strategy for financial advisors!

Deducting Financial Advisor Fees As Section 212 Expenses

It’s a long-recognized principle of tax law that in the process of taxing income, it’s appropriate to first reduce that income by any expenses that were necessary to produce it. Thus businesses only pay taxes on their “net” income after expenses under IRC Section 162. And the rule applies for individuals as well – while “personal” expenditures are not deductible, IRC Section 212 does allow any individual to deduct expenses not associated with a business as long as they are still directly associated with the production of income.

Specifically, IRC Section 212 states that for individuals:

“There shall be allowed as a deduction all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year:

- for the production or collection of income;

- for the management, conservation, or maintenance of property held for the production of income; or

- in connection with the determination, collection, or refund of any tax.”

Thus, investment management fees charged by an RIA (i.e., the classic AUM fee) are deductible as a Section 212 expense (along with subscriptions to investment newsletters and similar publications), along with any service charges for investment platforms (e.g., custodial fees, dividend reinvestment plan fees, under subsection (1) or (2) above), or any other form of “investment counsel” under Treasury Regulation 1.212-1(g). Similarly, tax preparation fees are deductible (under subsection (3)), along with any income tax or estate tax planning advice (as they’re associated with the determination or collection of a tax).

On the other hand, not any/all fees to financial advisors are tax-deductible under IRC Section 212. Because deductions are permitted only for expenses directly associated with the production of income, financial planning fees (outside of the investment management or tax planning components) are not deductible. Similarly, while tax planning advice is deductible (including income and estate tax planning), and tax preparation fees are deductible, the preparation of estate planning documents that implement tax strategies (e.g., creating a Will or revocable living trust with a Bypass Trust, or a GST trust) are not deductible (at best, only the “planning” portion of the attorney’s fee would be).

The caveat to deducting Section 212 expenses in recent years, though, was how they are deducted. Specifically, IRC Section 67 required that Section 212 expenses could only be deducted to the extent they, along with any/all other “miscellaneous itemized deductions”, exceed 2% of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). In turn, IRC Section 55(b)(1)(A)(i) didn’t allow miscellaneous itemized deductions to be deducted, at all, for AMT purposes.

Thus, in practice, Section 212 expenses – including fees for financial advisors – were only deductible to the extent they exceeded 2% of AGI (and the individual was not subject to AMT). Fortunately, though, given that financial advisors tend to work with fairly “sizable” portfolios, and the median AUM fee on a $1M portfolio is 1%, in practice the 2%-of-AGI threshold was often feasible to achieve, and thus many/most clients were able to deduct their advisory fees (at least up until they were impacted by AMT).

TCJA 2017 Ends The Deductibility Of Financial Advisor Fees

As a part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, Congress substantially increased the Standard Deduction, and curtailed a number of itemized deductions… including the elimination of the entire category of miscellaneous itemized deductions subject to the 2%-of-AGI floor. Technically, Section 67 expenses are just “suspended” for 8 years (from 2018 through the end of 2025, when TCJA sunsets) under the new IRC Section 67(g).

Nonetheless, the point remains: with no deduction for any miscellaneous itemized deductions under IRC Section 67 starting in 2018, no Section 212 expenses can be deducted at all… which means individuals lose the ability to deduct any form of financial advisor fees under TCJA (regardless of whether they are subject to the AMT or not!), and all financial advisor fees will be paid with after-tax dollars.

Notably, though, a retirement account can still pay its own advisory fees. Under Treasury Regulation 1.404(a)-3(d), a retirement plan can pay its own Section 212 expenses without the cost being a deemed contribution to (or taxable distribution from) the retirement account. And since a traditional IRA (or other traditional employer retirement plan) is a pre-tax account, by definition the payment of the advisory fee directly from the account is a pre-tax payment of the financial advisor’s fee!

Example 1. Charlie has a $250,000 traditional IRA that is subject to a 1.2% advisory fee, for a total fee of $3,000 this year. His advisor can either bill the IRA directly to pay the IRA’s advisory fee, or from Charlie’s separate/outside taxable account (which under PLR 201104061 is permissible and will not be treated as a constructive contribution to the account).

Given the tax law changes under TCJA, if Charlie pays the $3,000 advisory fee from his outside account, it will be an entirely after-tax payment, as no portion of the Section 212 expense will be deductible in 2018 and beyond. By contrast, if he pays the fee from his traditional IRA, his $250,000 taxable-in-the-future account will be reduced to $247,000, implicitly reducing his future taxable income by $3,000 and saving $750 in future taxes (assuming a 25% tax rate).

Simply put, the virtue of allowing the traditional IRA to “pay its own way” and cover its traditional IRA advisory fees directly from the account is the ability to pay the advisory fee with pre-tax dollars. Or viewed another way, if Charlie in the above example had waited to spend the $3,000 from the IRA in the future, he would have owed $750 in taxes and only been able to spend $2,250; by paying the advisory fee directly from the IRA, though, he satisfied the entire $3,000 bill with “only” $2,250 of after-tax dollars (whereas it would have cost him all $3,000 if he paid from his taxable account!)!

However, the reality is that IRAs are not the only type of investment vehicle that is able to implicitly pay its own expenses on a pre-tax basis!

The Pre-Tax Payment Of Investment Commissions And Fund Expenses

Mutual funds (including Exchange-Traded Funds) are pooled investment vehicles that collectively manage assets in a single pot, gathering up the interest and dividend income of the assets, and granting shares to those who invest into the fund to track their proportional ownership of the income and assets in the fund that are passed through to them, from which expenses of the fund are collectively paid.

The virtue of this arrangement – and the original underpinning of the entire Registered Investment Company structure – is that by pooling dollars together, investors in the fund can more rapidly gain economies of scale in the trading and execution of its investment assets (more so than they could as individual investors trying to buy the same stocks and bonds themselves), even as their proportionate share ownership ensures that they still participate in their respective share of the fund’s returns.

From the tax perspective, though, the additional “good news” about this pooled pass-through arrangement is that mechanically, any internal expenses of the pooled vehicle are subtracted from the income of the fund, before the remainder is distributed through to the underlying shareholders on a pro-rata basis.

Example 2. Jessica invests $1M into a $99M mutual fund that invests in large-cap stocks, in which she now owns 1% of the total $100M of value. Over the next year, the fund generates a 2.5% dividend from its underlying stock holdings (a total of $2.5M in dividends), which at the end of the year will be distributed to shareholders – of which Jessica will receive $25,000 as the holder of 1% of the outstanding mutual fund shares.

However, the direct-to-consumer mutual fund has an internal expense ratio of 0.60%, which amounts to $600,000 in fees. Accordingly, of the $2.5M of accumulated dividends in the fund, $600,000 will be used to pay the expenses of the fund, and only the remaining $1.9M will be distributed to shareholders, which means Jessica will only actually receive a dividend distribution of $19,000 (having been reduced by her 1% x $600,000 = $6,000 share of the fund’s expenses). Or stated more simply, Jessica’s net distribution is 2.5% (dividend) – 0.6% (expense ratio) = 1.9% (net dividend that is taxable).

The end result of the above example is that while Jessica’s investments produced $25,000 of actual dividend income, the fund distributed only $19,000 of those dividends – as the rest were used to pay the expenses of the fund – which means Jessica only ever pays taxes on the net $19,000 of income. Or viewed another way, Jessica managed to pay the entire $6,000 expense ratio with pre-tax dollars – literally, $6,000 of dividend income that she was never taxed on.

Which is significant, because if Jessica had simply owned those same $1M of stocks directly, earned the same $25,000 of dividends herself, and paid a $6,000 management fee to a financial advisor to manage the same portfolio… Jessica would have to pay taxes on all $25,000 of dividends, and would be unable to deduct the $6,000 of financial advisor fees, given that Section 212 expenses are no longer deductible for individuals! In other words, the mutual fund (or ETF) structure actually turns non-deductible investment management fees into pre-tax payments via the expense ratio of the fund!

In addition, the reality is that a commission payment to a broker who sells a mutual fund is treated as a “distribution charge” of the fund (i.e., an expense of the fund itself, to sell its shares to investors) that is included in the expense ratio. Which means a mutual fund commission itself is effectively treated as a pre-tax expense for the investor!

Example 2a. Continuing the prior example, assume instead that Jessica purchased the mutual fund investment through her broker, who recommended a C-share class that had an expense ratio of 1.6% (including an additional 1%/year trail expense that will be paid to her broker for the upfront and ongoing service).

In this case, the total expenses of her $1M investment into the fund will be 1.6%, or $16,000, which will be subtracted from her $25,000 share of the dividend income. As a result, her end-of-year dividend distribution will be only $9,000, effectively allowing her to avoid ever paying income taxes on the $16,000 of dividends that were used to pay the fund’s expenses (including compensation to the broker).

Ironically, the end result is that Jessica’s broker is paid a 1%/year fee that is paid entirely pre-tax, even though if Jessica hired an RIA to manage the portfolio directly, with the same investment strategy and the same portfolio and the same 1% fee, the RIA’s 1%/year fee would not be deductible anymore! And this result occurs as long as the fund has any level of income to distribute (which may be dividends as shown in the earlier example, or interest, or capital gains).

Notably, it does not appear that the new less favorable treatment for advisory fees compared to commissions was directly intended, nor did it have any relationship to the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule; instead, it was simply a byproduct of the removal of IRC Section 67’s miscellaneous itemized deductions, which impacted dozens of individual deductions… albeit including the deduction for investment advisory fees!

Tax Strategies For Deducting Financial Advisor Fees After TCJA

Given the current regulatory environment, with both the Department of Labor (and various states) rolling out fiduciary rules that are expected to reduce commissions and accelerate the shift towards advisory fees instead, along with a potential SEC fiduciary rule proposal in the coming year, the sudden differential between the tax treatment of advisory fees versus commissions raises substantial questions for financial advisors.

Of course, the reality is that not all advisory fees were actually deductible in the past (due to both the 2%-of-AGI threshold for miscellaneous itemized deductions, and the impact of AMT), and advisory fees are still implicitly “deductible” if paid directly from a pre-tax retirement account. Nonetheless, for a wide swath of clients, investment management fees that were previously paid pre-tax will no longer be pre-tax if actually paid as a fee rather than a commission.

In addition, given that the now-disparate treatment between fees and commissions appears to be an indirect by-product of simply suspending all miscellaneous itemized deductions, it’s entirely possible that subsequent legislation from Congress will “fix” the change and reinstate the deduction. After all, investment interest expenses remain deductible under IRC Section 163(d) to the extent that it exceeds net investment income; accordingly, the investment advisory fee (and other Section 212 expenses) might similarly be reinstated as a similar deduction (to the extent it exceeds net investment income). At least for those whose itemized deductions in total can still exceed the new, higher Standard Deduction that was implemented under TCJA (at $12,000 for individuals and $24,000 for married couples).

Unfortunately, one of the most straightforward ways to at least partially preserve favorable tax treatment of advisory fees – to simply add them to the basis of the investment, akin to how transaction costs like trading charges can be added to basis – is not permitted. Under Chief Counsel Memorandum 200721015, the IRS definitively declared that investment advisory fees could not be treated as carrying charges that add to basis under Treasury Regulation 1.266-1(b)(1). Which means advisory fees may be deducted, or not, but cannot be capitalized by adding them to basis as a means to reduce capital gains taxes in the future (although notably, CCM 200721015 did not address whether a wrap fee, which supplants individual trading costs that are normally added to basis, could itself be capitalized into basis, as long as the fee is not actually for investment advice!).

Nonetheless, the good news is that there are at least a few options available to financial advisors – particularly those who do charge now-less-favorable advisory fees – who want to maximize the favorable tax treatment of their costs to clients, including:

- Switching from fees to commissions

- Converting from separately managed accounts to pooled investment vehicles

- Allocating fees to pre-tax accounts (e.g., IRAs) where feasible

Switching From Advisory Fees To Commissions

For the past decade, financial advisors from all channels have been converging on a price point of 1%/year as compensation (to the advisor themselves) for ongoing financial advice, regardless of whether it is paid in the form of a 1% AUM fee for an RIA, or a 1% commission trail (e.g., via a C-share mutual fund) for a registered representative of a broker-dealer.

Of course, the caveat is that once a broker actually gives ongoing financial advice that is more than solely incidental to the sale of brokerage services, and/or receives “special compensation” (a fee for their advice), the broker must register as an investment adviser and collect their compensation as an advisory fee anyway. Which is why the industry shift to 1%/year compensation for ongoing advice (and not just the sale of products) has led to an explosion of broker-dealers launching corporate RIAs, so their brokers can switch from commissions to advisory fees.

Given these regulatory constraints, it may not often be feasible anymore for those who are dual-registered or hybrid advisors to switch their current clients from advisory fee accounts back to commission-based accounts – especially for those who have left the broker-dealer world entirely and are solely independent RIAs (with no access to commission-based products at all!).

Still, for those who are still in a hybrid or dual-registered status, there is at least some potential appeal now to shift tax-sensitive clients into C-share commission-based funds, rather than using institutional share classes (or ETFs) in an advisory account.

Of course, it’s also important to bear in mind that many broker-dealers have a lower payout on mutual funds than what an advisor keeps of their RIA advisory fees, and it’s not always possible to find a mutual fund that is exactly 1% more expensive solely to convert the advisor’s compensation from an advisory fee to a trail commission. And some clients may already have embedded capital gains in their current investments and not be interested in switching. And there’s a risk that Congress could reinstate the investment advisory fee deduction in the future (introducing additional costs for clients who want to switch back).

Nonetheless, at the margin, for dual-registered or hybrid advisors who do have a choice about whether to be compensated from clients by advisory fees versus commissions, there is some incentive for tax-sensitive clients to use commission-based trail products (at least in taxable accounts where the distinction matters, as within an IRA even traditional advisory fees are being paid from pre-tax funds anyway!).

Creating A Firm’s Own Proprietary Mutual Fund Or ETF

For very large advisory firms, another option to consider is actually turning their investment strategies for clients into a pooled mutual fund or ETF, such that clients of the firm will be invested not via separate individual accounts that the firm manages, but instead into a single (or series of) mutual fund(s) that the firm creates for its clients. The appeal of this approach: the firm’s 1% advisory fee may not be deductible, but its 1% investment management fee to operate the mutual fund would be!

Unfortunately, in practice there are a number of significant caveats to this approach, including that the client psychology of holding “one mutual fund” is not the same as seeing the individual investments in their account, the firm loses its ability to customize client portfolios beyond standardized models being used for each of their new mutual funds, the approach necessitates a purely model-based implementation of the firm’s investment strategies in the first place, it’s no longer feasible to implement cross-account asset location strategies, and there are non-trivial costs to creating a mutual fund or ETF in the first place. For which the proprietary-fund-for-tax-savings strategy is again only relevant for taxable accounts (and not IRAs, not tax-exempt institutions) in the first place.

Nonetheless, for the largest independent advisory firms, creating a mutual fund or ETF version of their investment offering, if only to be made available for the subset of clients who are most tax-sensitive, and have large holdings in taxable accounts (where the difference in tax treatment matters), may find the strategy appealing.

Notably, for this approach, the firm wouldn’t even necessarily need to pay itself a “commission”, per se, but simply be the RIA that is hired by the mutual fund to manage the assets of the fund, and simply be paid its similar/same advisory fee to manage the portfolio (albeit in mutual fund or ETF format, to allow the investment management fee to become part of the expense ratio that is subtracted from fund income on a pre-tax basis).

Paying Financial Advisory Fees From Traditional IRAs (To The Extent Permissible)

For those who don’t want to (or can’t feasibly) revert clients to commission-based accounts, or launch their own proprietary funds, the most straightforward way to handle the loss of tax deductibility for financial advisor fees is simply pay them from retirement accounts where possible to maximize the still-available pre-tax treatment. As again, while the TCJA’s removal of IRC Section 67 means that Section 212 expenses aren’t deductible anymore, advisory fees are still Section 212 expenses… which means IRAs (and other retirement accounts) can still pay their own fees on their own behalf. On a pre-tax basis, since the account itself is pre-tax.

In practice, this means that advisory firms will need to bill each account for its pro-rata share of the total advisory fees, given that IRAs should only pay advisory fees for their own account holdings and not for other/outside accounts (which can be deemed a prohibited transaction that disqualifies the entire IRA!). In addition, an IRA can only pay an investment management fee from the account, and not financial planning fees (for anything beyond the investment-advice-on-the-IRA portion), which limits the ability to bill financial planning fees to IRAs, and even raises concerns for “bundled” AUM fees that include a significant financial planning component. And of course, it’s only desirable to bill pre-tax traditional IRAs, and not Roth-style accounts (which are entirely tax-free); Roth fees should still be paid from outside accounts instead.

The one caveat to this approach worth recognizing, though, is that while paying an advisory fee from an IRA is pre-tax (i.e., deductible), while paying from an outside taxable account is not, in the long run the IRA would have grown tax-deferred, while a taxable brokerage account is subject to ongoing taxation on interest, dividends, and capital gains. Which means eventually, “giving up” tax-deferred growth in the IRA on the advisory fee may cost more than trying to preserve the pre-tax treatment of the fee in the first place.

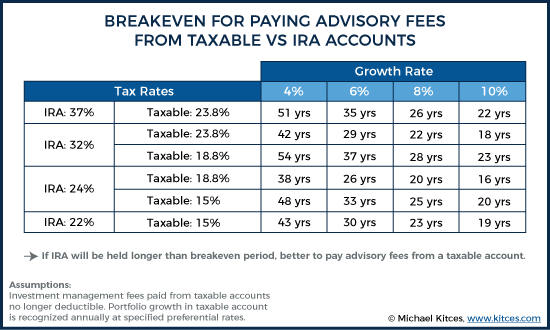

However, in reality, the breakeven periods for it to be superior to pay an advisory fee with outside dollars are very long, especially in a high-valuation (i.e., low-return) and low-yield environment. Accordingly, the chart below shows how many years an IRA would have to grow on a tax-deferred basis without being liquidated, to overcome the loss of the tax deduction that comes from paying the advisory fee on a non-deductible basis in the first place. (Assuming growth in the taxable account is turned over every year at the applicable tax rate.)

As the results reveal, at modest growth rates it is a multi-decade time horizon, at best, to recover the “lost” tax value of paying for an advisory fee with pre-tax dollars. And the higher the income level of the client, the more valuable it is to pay the advisory fee from the IRA (as the implicit value of the tax deduction becomes even higher). Nonetheless, at least some clients – especially those at lower income levels, with more optimistic growth rates, and very long time horizons – may at least consider paying advisory fees with outside dollars and simply eschewing the tax benefits of paying directly from the IRA.

In the end, the reality is that when the typical advisory fee is “just” 1%, the ability to deduct the advisory fee only saves a portion of the fee, and the alternatives to preserve the pre-tax treatment of the fee have other costs (from the expense of using a broker-dealer, to the cost of creating a proprietary mutual fund or ETF, or the loss of long-term tax-deferred growth inside of an IRA), which means in many or even most cases, clients may simply continue to pay their fees with their available dollars. Especially since the increasingly-relevant “financial planning” portion of the fee isn’t deductible anyway.

Nonetheless, for more affluent clients (in higher tax brackets), the ability to deduct advisory fees can save 1/4th to 1/3rd of the total fee of the advisor, or even more for those in high-tax-rate states, which is a non-trivial total cost savings. Hopefully, Congress will eventually intervene and restore the tax parity between financial advisors who are paid via commission, versus those who are paid advisory fees. For the time being, though, the disparity remains, which ironically has made tax planning for advisory fees itself a compelling tax planning strategy for financial advisors!

So what do you think? Are you maximizing billing traditional IRA advisory fees directly to those accounts after the TCJA? Will larger firms creating proprietary mutual funds or ETFs to preserve pre-tax treatment for clients? Will Congress ultimately intervene and restore parity between commission- and fee-based compensation models for advisors? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

You quote “Roth fees should still be paid from outside accounts instead.” In a 2012 article it is mentioned that the mathematics bear out this statement. Do you have a breakeven chart like the one for Traditional IRA’s in this article?

Hi Michael, here’s what I don’t understand: my Fidelity account fees, which are 100% paid for the purposes of generating the proceeds, are equal to the gains. Meaning, I made zero profit and yet because I cannot deduct the account fees, I am paying taxes, which means I take risk investing my money only to pay taxes on profit I have not even made. How does that even remotely make sense?