Executive Summary

Economists have long studied the importance of property rights in a wide range of settings. From collectively avoiding circumstances that may lead to an inefficient use of resources (e.g., the "tragedy of the commons"), to simply understanding what conditions best promote the development of a wealthy and prosperous society, property rights are an important economic concept that can be applied in many contexts. Of interest to financial advisors, a recent study by Chris Clifford and William Gerken examined whether and how who "owns" a client relationship in a financial advisory firm - the firm, or the advisor themselves - influences that financial advisor in the future, based on the behavior of financial advisors at firms that joined the Broker Protocol (versus those that did not).

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – takes a deep dive into this recent Broker Protocol study, examining how "ownership" of a client relationship in a financial advisory firm impacts not just the success of the firm, but whether and how much the advisor reinvests into themselves, consumer well-being and advisor misconduct rates, and even the development of the advisory industry as a whole!

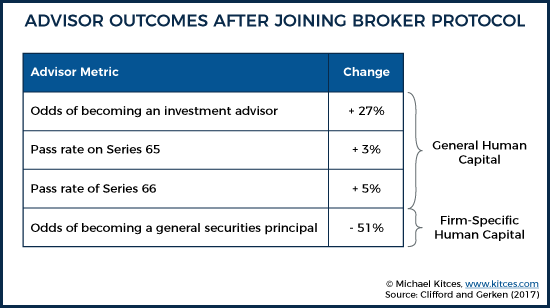

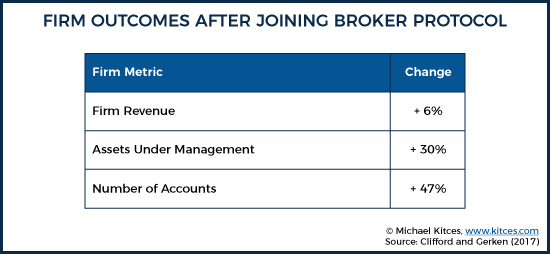

The development of the Broker Protocol was significant because it, for the first time, formalized exactly what information brokers can (and cannot!) take with them when changing from one firm to another, which not only helped provide a pathway for brokers to change firms without getting sued, but effectively shifted the "ownership rights" of the client relationship from the firm to the advisor (who can now take the information and relationship with them when switching to a new firm). Accordingly, Clifford and Gerkin utilized publicly available data on broker-dealers in conjunction with their timing of joining the Broker Protocol to evaluate how broker behavior changed before and after being given greater ownership over the client relationship. The astounding results: giving a greater level of ownership in the client relationship to the broker resulted in less broker misconduct, more broker investment in their general human capital, and an increase in firm revenue, client assets, and the number of client accounts (even though brokers did invest less into firm-specific human capital along the way).

Notably, the dynamics which led to the creation of Broker Protocol among broker-dealers largely exist within RIAs as well. Restrictive covenants commonly found at RIAs (such as non-solicits, or, less commonly, non-competes), can influence the level of advisor "ownership" over client relationships. Of course, both firms and advisors can have good reasons to accept such agreements (e.g., firms may be hesitant to give inexperienced advisors opportunities to work with clients if they could just "steal" clients without recourse), but it's important to understand and carefully consider the implications of such arrangements. As ultimately these arrangements impact factors such as the level of advisor talent across the entire industry (as advisors are more inclined to invest in their own human capital when they have greater ownership of client relationships), firm success (as a more talented workforce can be a net improvement for firms, even if employee turnover is higher), consumer well-being (as policies which restrict advisor mobility keep talented advisors "trapped" in lower-quality firms, which ultimately leads to lower service for consumers), and even industry regulatory and ethical concerns (as consumers themselves may not be aware that restrictive covenants may influence their ability to work with their trusted advisor, and consumers may not consent to such arrangements if they were disclosed).

Ultimately, there are steps that firms can take to reduce the harmful elements of restrictive covenants... from adopting an RIA equivalent to Broker Protocol, to regulatory intervention to restrict certain practices, and even pre-arranged terms for buying an advisor's client base if they wish to a leave a firm... but the key point is to acknowledge that advisor ownership of client relationships does influence advisor behavior in important ways, and that while it may be scary for a firm to vest more ownership in the client relationship to their advisors, the data shows that doing so is on average a benefit to both the advisor and their firm, as well as the consumer, and the industry as a whole!

Does It Matter Who “Owns” A Client Relationship?

Property rights are a fundamental concept in economics. How ownership of goods and resources are determined, enforced, and transferred among individuals has a tremendous influence on societal well-being. Ill-defined or weakly enforced property rights can lead to an inefficient (and potentially devastating) use of scarce resources—such as the famous “tragedy of the commons”, in which a pasture shared collectively by a community of herders may become overgrazed as each herder pursues actions which are in his or her individual best interest (graze as many cattle as possible) to the detriment of the resource itself (overgraze until the land is fully depleted).

The famous solution to this problem is to assign property rights in a manner that allows individuals to pursue their own self-interest without harming the collective interest. Of course, precisely how to do that remains a hotly debated topic. Since the time of Adam Smith, the rise of market democracies brought with them an explosion of wealth (what economist Dierdre McCloskey has called the “hockey stick” of human prosperity), indicating that well-defined property rights and quality legal/political institutions do play an important role in creating the conditions needed for wealth to grow, but there’s no shortage of debate surrounding precisely what arrangements provide the “best” conditions for promoting human prosperity.

As is the case with many other ideas in economics, the concept of “property rights” can be applied in contexts outside of what has historically been most common. Recently, Chris Clifford and William Gerken, both of the University of Kentucky, examined property rights in a financial advisory context, specifically looking at whether who “owns” a client relationship influences the behavior of financial advisors.

Not surprisingly, the researchers found that ownership of a client relationship does influence financial advisor behavior. Specifically, the researchers found that when advisors are given ownership of the relationship, they generate fewer customer complaints, are more likely to invest in their own human capital, but are less likely to invest in firm-specific human capital.

Broker Protocol and the Assignment of Client Property Rights

A key component to Clifford and Gerken’s analysis is unique insight gleaned from the “Broker Protocol”—an agreement originally signed in 2004 between Smith Barney, Merrill Lynch, and UBS, establishing what client information registered representatives would be allowed to take with them when changing broker-dealers. Prior to Broker Protocol, client information was treated as a “trade secret” of the brokerage firm, and brokers were not allowed to take their now-former company’s intellectual property with them when they left (in addition to the potential that it could constitute a breach of client privacy). Which meant brokers effectively had to leave their clients behind as “property of the firm” when they left and switched to a new firm (or, at least risk a major legal battle to try to bring them along). By creating the Broker Protocol, it became easier for departing brokers to take “their” clients with them, by reducing the business risk and potential legal costs they could face.

Notably, though the Broker Protocol was effectively not just a "cease fire" between the major wirehouses, outlining specifically how brokers could change firms in a manner that would avoid a costly battle between the firms, but firms that signed onto the Broker Protocol effectively transferred ownership of client relationships from the firm to the broker. Which proved popular, as since 2004, over a thousand firms have joined the protocol, and many thousand brokers have used the protocol to successfully transition from one firm to another without a costly battle, while retaining access to the client contact information necessary to be able to do retain "their" client relationship.

Of course, the client still ultimately chooses whether to move with the broker, and who to work with—this isn’t an absolute transfer of property rights, and there are still important client privacy rules and other limitations that apply—but relative to the risk of being sued, and hit with a Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) as soon as a broker left a firm (to keep the broker from soliciting clients to follow them), firms that signed the Broker Protocol did assign important new “property rights” in their clients to their brokers.

Entering Broker Protocol and (Subsequent) Advisor Misconduct

Because the Broker Protocol document (and the list of participating firms) is publicly available, along with important industry misconduct information (e.g., via BrokerCheck and the Investment Adviser Public Disclosure website), Clifford and Gerken were able to create a dataset which looks at employee behavior before and after a firm entered Broker Protocol, as well as impacts on the firms themselves.

The researchers found that when a firm entered the protocol, advisors began to take better care of their clients, with customer disputes dropping an incredible 42%. This outcome is not necessarily surprising, as it makes sense that brokers would invest more in a relationship once they are given the possibility of taking that relationship with them in the future. Like a herder given a plot of land to call their own, a broker has an increased incentive to nurture the resources they are managing and ensure they are not abused for short-term gains.

Entering Protocol and Human Capital Investment

Additionally, the researchers used FINRA exams as a way to look at how brokers begin investing in individual and firm-specific human capital after entering Broker Protocol.

Economists note that it is important to distinguish between different types of human capital. General human capital refers to human capital which is valuable to any employer. A common example of general human capital is education (assuming that education actually builds human capital and is not just a signal of it). The skills and knowledge acquired by a college graduate are “generally” useful regardless of whether they work for Company ABC or Company XYZ. By contrast, firm-specific human capital refers to skills and knowledge that are only useful within a single particular firm. For instance, suppose a company has proprietary planning software that varies dramatically from all other tools on the market… when an employee of Company ABC invests time and effort in developing proficiency using their proprietary software, they have developed firm-specific human capital, since those skills and knowledge are valuable at that specific firm, but will not be useful if the employee leaves for a new Company XYZ.

It’s important to distinguish these different types of human capital, as they have important implications for human capital investment for both firms and employees. For instance, relative to firm-specific human capital, firms may be reluctant to invest in general human capital of employees, out of fear that they may simply be training their competition. Of course, firms do benefit from having employees with high-levels of general human capital as well, so it’s not as if they will never invest in general human capital of employees, but, all else being equal, firms may perceive a higher ROI on their investment in employees if it boosts the employees’ productivity and earning potential within the firm in a way that isn’t likely to benefit them outside the firm. By contrast, all else being equal, employees will prefer the opposite. Human capital which boosts an employee’s earning potential regardless of where they work will be preferred by an employee relative to human capital which is only useful within a single firm.

In this context, Clifford and Gerken used data on industry licenses to examine whether brokers were investing in more or less general/firm-specific human capital before and after entering the Protocol. Specifically, they use the Series 65 and Series 66 exams as indicators of investment in general human capital, since these licenses can easily be transferred between firms. The researchers use the Series 24 exam (general securities principal exam) as an indicator of firm-specific human capital, since serving as a principal for a firm requires the application of more firm-specific policies in procedures. In other words, although the Series 24 license may transfer from one firm to another, earning one’s Series 24 license requires greater time and effort dedicated to learning firm-specific information (relative to the Series 65 and 66), and therefore can be seen as an investment which is less transferable between firms.

The researchers find that entering the Protocol does increase employee investment in human capital. For instance, after entering the Protocol, the odds that an employee will become a Series-65-licensed investment advisor increase 27%. Additionally, advisor test scores on the Series 65 and 66 exams increase as well when a firm is in the Protocol. Clifford and Gerken found that advisors at firms in the protocol were 3.33% more likely to pass the Series 65, and 5.05% more likely to pass the Series 66. At the same time, however, employee likelihood of investing in firm-specific human capital declines after entering the Protocol. Specifically, the odds that an employee became a Series-24-licensed principal decreased by 51% after entering the Protocol!

Other Effects of Entering the Protocol

Consistent with one of the primary fears that firms may have when giving advisors greater ownership over the client relationship, Clifford and Gerken do find that firms which enter the Protocol experience higher advisor turnover (i.e., advisors switching firms)—with firms experiencing both higher rates of advisors leaving for competitors, as well as higher rates of attracting advisors away from competitors.

However, the researchers are careful to note that this should not necessarily be seen as zero-sum shifting of advisors from one firm to another. Since advisors are also increasing their investment in general human capital (and presumably their effort in building their client base), the increasing productivity of advisors can result in a win-win situation for all, despite the higher levels of turnover.

Consistent with this idea, the researchers find that after joining the Protocol firms experience 6% higher revenues, 30% higher assets under management, and a 47% increase in the number of client accounts, even as their advisor (and client) turnover increases, too.

Why Clifford & Gerken’s Broker Protocol Study Matters

Ultimately, the Clifford and Gerken study on the impact of the Broker Protocol—and more generally, the consequences of giving advisors “rights” to their client relationships—matters, for a number of reasons. With consequences not just for financial advisors and their firms directly, but also the industry at large, and for consumers as well.

Why Flexible “Ownership” Of Clients Matters to Firms and Advisors

From the advisory firm perspective, it’s important to understand how the policies the firm puts in place may influence its own advisors’ professional development and career trajectory. (And equally important for advisors to consider the ramifications for their own careers by choosing a Protocol vs non-Protocol firm.)

Because as the Clifford and Gerken study shows, while there may certainly be good reasons for firms to have restrictive covenants (e.g., non-solicit agreements) in place, firms that create environments with strong restrictive covenants may want to consider how this may influence their advisors’ behavior in subtle but important ways.

For instance, it’s unlikely that advisors in firms that had not entered the Broker Protocol woke up the morning of their firm’s signing and consciously decided they were going to service clients better and learn to more effectively avoid circumstances that could result in a client complaint. Most advisors probably felt they were doing this all along. But the reality is that this new assignment of property rights and the potential to have greater mobility should an advisor feel that a better opportunity was available elsewhere appears to have been enough to motivate advisors to actually take better care of their clients even when they hadn’t left their firms.

Further, not only did these advisors take better care of their clients, but they began taking better care of themselves too by investing in themselves more. And when thinking over the long timeframe of a young advisor’s career, these changes are not insignificant. Minor investments in one’s own human capital can easily compound out into larger changes over the course of one’s career. As a result, there’s a true cost to firms (the long-term deterioration of their human capital relative to its potential) in creating an environment where an advisor feels restricted. Of course, it’s entirely possible that those restrictions are worth the benefits to the firm (e.g., where the restrictive covenants are profitable enough to be worth causing their advisors to lag in the development of their general human capital, especially if they build more firm-specific human capital along the way), but the data suggests that advisors themselves are giving careful thought to these competing factors as well. Because ideally, advisors will likely try to find an environment that contains the best of both worlds—such as working for a high-growth firm with lots of opportunities to develop human capital, but one that also has “exit policies” which do not discourage advisor ownership of relationships (e.g., pre-established terms under which advisors can “buy-out” the clients they serve as a lead on, if they wish to exit the firm). And will choose whichever firm closest matches their personal goals and willingness to accept trade-offs.

Over the long run, these dynamics also matter because of the conflicts that occur when advisors begin to plan for their own future. For instance, it’s not hard to imagine how entrepreneurially-minded employees with an itch to potentially go out on their own one day could find themselves conflicted between a desire to grow their business development skills, and a fear that actually succeeding in doing so could result in “losing” a prospective future client due to a non-solicitation agreement. This could result in a lose-lose scenario. It’s a loss to the advisor because they hold themselves back from developing key skills—potentially needlessly deferring that development to the future, and ultimately attempting to build those skills under conditions that are less conducive to their success as well. But it’s a loss to the firm, since the firm may lose out an opportunity to help the advisor hone their skills and realize that perhaps the advisor is better off maintaining the support of the firm rather than going off on their own. Not to mention that the advisor grows their client base more slowly because they don’t feel as motivated to invest in their human capital in the first place. Of course, perhaps an advisor does bring in clients and then does decide to go off on their own in the future, but even if this is the case, it’s not as if a split must inherently leave each party worse off—especially because when all firms engage in similar behavior, firms have the potential to attract as many good advisors in as they risk losing, and the whole industry collectively ends out with more growth and revenue along the way!

Why Giving Advisors Client Rights Matters to the Industry

Though it’s perhaps a less obvious implication of Clifford and Gerken’s study, their point about higher advisor mobility not being a zero-sum outcome is crucially important to understand and reiterate.

Clifford and Gerken reference a 1999 paper by Ronald Gilson which argued that, at least in part, California’s Silicon Valley rose to greater prominence than Massachusetts’ Route 128 due to California’s unwillingness to enforce non-compete agreements, and the positive spill-over that happens when employees invest more in themselves, thereby raising the entire stock of human capital and the potential gains to be received from greater innovation. Notably, this historical case study is consistent with Clifford and Gerken’s findings, which suggests that greater advisor investment in an advisor’s own human capital when they are given more mobility can more than offset the firm losses due to higher mobility (especially when writ large across the entire industry).

And notably, this phenomenon is not unique to the brokerage channel. Ironically, in the early years, the RIA channel likely benefitted from the perceived improvements in mobility that come from actually being “the firm owner” who controls the client relationships directly. Yet as RIA firms have grown, and hired more and more employee advisors, those firms are increasingly binding their employees with non-compete or, more commonly, non-solicitation agreements, which can have the same adverse impact on advisors as occurs in firms that refused to adopt the Broker Protocol. Through the continued use of such restrictive covenants, the net effect may be that we all lose. And over time, while it may be the case that firms are less likely to lose an existing employee with such covenants in place, firms may be also less likely to gain a future employee who currently works at another firm in the area and is investing in their own skills.

Of course, it’s not literally the case that all firms will necessarily win by adopting less restrictive covenants in their employment agreements. There would likely be some net flows from certain more successful firms from other less successful firms. And arguably, some types of firm structures are especially conducive to having reasonable restrictive covenants (e.g., where the firm does all the marketing and sales, and the advisors didn’t have to develop their own clients in the first place). Nonetheless, the point remains that when the industry grows as a whole by imposing fewer restrictions on advisors, and high-quality firms can use such flexibility to attract and retain top talent, the subset of firms that remain overly restrictive run the risk of losing their ability to attract and retain quality talent (or retain but under-develop their talented advisors due to the adverse incentives for the advisor who has no “rights” in their own client relationships).

Why Advisor Mobility Matters to Consumers

Advisor mobility, and the ability of advisors to retain their client relationships when switching firms, is an issue that matters for consumers as well.

Less ability for advisors to move to the firms which can enable them to provide higher levels of service (and less general human capital investment among advisors across the board), results in a lower quality client experience and less opportunity to help consumers reach their financial goals. To the extent that, all else being equal, talent tends to flow to “better” firms, reduced mobility can end out keeping clients engaged with less talented advisors (because they didn’t invest in themselves), locked into lower quality firms (because the advisor has no means to move the client to a higher quality firm).

Further, there’s also an issue surrounding client autonomy and the level of disclosure clients should have regarding any restrictive covenants that may keep them from working with their preferred advisor. While consumer expectations likely vary by context (e.g., a consumer asking their banker if someone in the firm’s wealth management department could meet with them, versus a consumer who reaches out to a friend they know works in the industry), the intimate nature of the advisor-client relationship likely suggests that many clients feel more loyalty (and more preference in working with) their specific advisor, rather than the firm that “technically” owns the relationship. Such consumers may be surprised to learn that their trusted advisor can be barred from soliciting their future business if they leave or are terminated from their existing firm. In extreme cases of non-compete and non-accept agreements, the client wouldn’t even be permitted to work with the advisor they wanted to work with, due to the limitations imposed on the advisor by his/her former firm.

Eventually, limitations on advisors that actually limit consumer choice (whether with respect to which advisor the client wants to work with, or on what platform the client wants to be on when working with that client) may even draw in regulator to intervene. In fact, some consumers may already find such terms unacceptable, if the situation was fully disclosed to them in the first place (and arguably it’s reasonable for consumers to at least be made aware of what, if any, restrictions their advisor may have on contacting them or working with them if they change firms!).

How Can Firms Equitably “Give” Advisors Ownership of Clients?

So how should firms balance out the needs to protect the business, and a desire to encourage their advisors to grow and invest in themselves (to the long-term benefit of the advisor, the industry, and hopefully the firm itself).

One approach to increasing advisor mobility and better vesting “rights” in the client relationship to the advisor would be making the Broker Protocol mandatory (i.e., imposed directly by a regulator, rather than being self-imposed by agreement of the brokerage firms), and RIA firms could adopt an agreement similar to the Broker Protocol (customized to incorporate unique aspects of the RIA model). Of course, if firms have no way of protecting themselves from attempts to “steal” their clients, then firms may be less willing to give inexperienced advisors meaningful opportunities to engage with clients in the first place, particularly in the case where a firm is literally handing over a client for an advisor to manage. Thus, it can be perfectly rational for each party to agree that if the client is being handed to the advisor, the advisor won’t be permitted run off with a list of client names and try and steal them from the firm. While clients that the advisor developed directly, albeit on the firm’s platform, would still remain “the advisor’s” relationship, not the firm’s.

More generally, it’s important to distinguish between clients “handed” to an advisor, and relationships and advisor develops on their own, when considering the property rights of client relationships. As arguably, “who developed the initial client relationship” arguably is a reasonable way to determine whether the firm or the individual advisor should be in control of the relationship rights. Although from the firm’s perspective, it’s worth acknowledging that even in cases where an advisor is developing relationships on their own, most firms are still contributing in a meaningful way to helping an advisor establish and retain the client relationship—either through the overall service infrastructure the firm provides, guidance and training from senior firm members, or simply by leveraging the brand of the firm to help establish credibility with clients.

One solution to balance the interests of both parties, without an agreement similar to Broker Protocol, could be to simply agree to a pre-determined buy-out in the case that an advisor wants to leave a firm and take their clients with them. If an advisor decides they want to leave a particular company, then they would be welcome to do so and could take their clients with them, but must buy them at a pre-determined cost that is fair to both parties. Under such an arrangement, advisors would not be disincentivized from investing in themselves, and could choose to leave (with or without clients) on their own terms. Further, such an approach has the added benefit of promoting open dialogues, which may reduce advisor turnover in the first place. If advisors can openly talk about leaving, this may help bring to light adjustments that can be made to improve the current advisor-firm relationship, rather than needing to separate at all.

However, firms and advisors may also want to consider that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be what’s best, given advisors at different stages of their careers as well. It’s of course reasonable that an advisor joining a firm and bringing $100M in assets would not want to pay the same amount to take (or “buy back”) their clients as a junior advisor who was handed $100M in client assets to serve as a lead advisor on. Alternatively, it could be the case that it’s best for an advisor bringing in $100M in client assets to be entirely bought-out by the firm (in either cash or equity), so that the firm truly does own everything, and the valuation does not get unnecessarily complicated.

While firms have lots of options for considering how client property rights can best be assigned within a firm, they key point is simply to acknowledge that how property rights in the client relationship are assigned does matter. The assignment of client relationship property rights not only influences advisor behavior, but it has implications for the talent level of the advisory industry more broadly as well, along with the well-being and autonomy of consumers. Which means that ultimately, giving advisors more ownership over clients can be a win-win for advisors and firms (plus a win for the industry and consumers as well)!

So what do you think? Does who “owns” a client relationship matter? Are you surprised that brokers treat their clients better when given ownership over the relationship? How could advisor mobility be promoted on the RIA side of the industry? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!