Executive Summary

For financial advisors, the new Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction (also known as the IRC Section 199A deduction, or the pass-through deduction) presents not just many tax planning opportunities for small business owner clients, but also tax planning opportunities for financial advisors themselves as small business owners. The caveat, however, is that the 20% QBI deduction may be very limited for financial advisors, because they are classified as "Specified Service Business" owners under the new rules, and, as a result, any "high income" advisors (defined as those whose taxable income exceeds $315,000 when filing a joint return, or $157,500 when filing otherwise) are subject to a phaseout of their potential full QBI deduction.

In this guest post, Jeffrey Levine of BluePrint Wealth Alliance, and our Director of Advisor Education for Kitces.com, examines how high-income financial advisors (and other Specified Service Businesses) can utilize strategies to get the most benefit from their QBI deduction, including spinning off and renting back depreciable property, creating a PEO and leasing back employees, condensing lifetime giving via the use of a donor-advised fund, and other strategies!

The good news of the new QBI rules, and the phaseout for Specified Service Businesses (including financial advisors), is that it still takes a fairly substantial income to phase out the deduction, and for those under the income thresholds, the full QBI deduction remains available. On the other hand, because the QBI deduction phaseout is based on total household income from all sources (albeit after all deductions), even advisors who themselves don't earn more than the threshold amount may still end out phasing out some or all of the deduction based on other income (e.g., spousal income, real estate income, portfolio income, etc.).

Fortunately, though, not all is lost for financial advisors who have entered into the QBI phaseout zone. First and foremost, advisors can look to strategies that convert the advisor’s specified service business income into "other" income derived from a non-specified trade or service business, such as by spinning off any firm-owned real estate into a separate entity (and leasing it back at fair market value), spinning off non-advisory employees and leasing them back through a professional employer organization (PEO) (as a PEO would be eligible for a QBI deduction, so long as it is not deemed an advisory business), or holding the firm's intellectual property under a different entity and then licensing it back to the firm (as the intellectual property income may be eligible for a QBI deduction). The net result of such strategies is that the advisor's total income is the same, but occurs by reducing the amount of specified service business QBI generated from their practice (as rent, employee leasing, etc, are deductible business expenses), while simultaneously increasing the amount of QBI generated from the separate (non-specified-service and QBI-deduction-eligible) businesses.

For those who are in the midst of the QBI phaseout zone, planning can be even more impactful, as marginal tax rates during the QBI phaseout can spike as high as 64%... which may lead advisors to increase investment into the firm (as deductions are more valuable at the higher rate!), shift income to other years (that are outside the phaseout zone), or potentially even cut back on their workload (if they're really only keeping 36 cents on the dollar before the additional impact of state income taxes!).

Ultimately, the key point is to acknowledge that high-income financial advisors (and other specified service business owners) have considerable opportunity to plan around the new QBI phaseout zone... even if their total income is within or well beyond the QBI phaseout zone! While the new rules can be a bit tricky (and strategies could shift as the IRS provides more guidance going forward), it appears that QBI strategies will be a key focus going forward, and present a considerable planning opportunity for advisors (and their clients!) to reduce their overall tax burden!

Application of the QBI Deduction to “High-Income Advisors”

While financial advisors with more “modest” taxable income will be able to claim a full QBI deduction, “high-income advisors” may have their QBI deduction reduced or completely eliminated. That’s because financial services professionals are considered to be engaged in a “specified service business”, which is the proverbial kiss of death when it comes to the QBI deduction. Because after a brief phase-out range of $100,000 for joint filers and $50,000 for all other filers, the QBI deduction is completely eliminated for any income associated with a specified service business. Thus, advisors who are married and file a joint return, and have more than $415,000 ($315,000 threshold plus $100,000 phase-out range) of taxable income, or advisors who file using any other filing status and have more than $207,500 ($157,500 threshold plus $50,000 phase-out range) of taxable income, cannot receive any QBI deduction for income related to their financial advisory practice.

Given the nature of the financial services business, many financial advisors will find themselves in this position of being classified as a “high-income advisor”. In such cases, it will often pay to consider ways of reducing taxable income, or to attempt to engage in strategies designed to shift the advisor’s QBI to other entities not classified as specified service businesses (as discussed further in the sections below).

Of course, an advisor’s ability to do either may be severely limited by their specific set of circumstances, and level of control over the advisory practice in which they work. Not surprisingly, the greater the control an advisor has over their business, the more likely it is that they will be able to take certain steps to help them maximize their QBI deduction.

Planning for Advisors With Income Well in Excess of Their Phase-Out Range

For the most financially successful advisors, there is simply no way that they are going to be able to reduce their household taxable income enough in order to qualify for the QBI deduction on any of their qualified business income. They are just too far above their applicable phase-out threshold to ever hope to get under it (cue the world’s smallest violin).

Nevertheless, such advisors may still qualify to receive at least some QBI deduction… just not for income related to their financial services work. Instead, a deduction will potentially be available for qualified business income generated from non-specified service businesses. In other words, the goal for advisors who are well above the income threshold for the Specified Service Business test is to transmute some of their financial services income into potentially-QBI-eligible other business income instead.

Note: For advisors with taxable income in excess of the top of their applicable QBI deduction phase-out range, a QBI deduction is only potentially available because the QBI deduction is still limited to no more than the greater of 1) 50% of W-2 wages paid by the non-specified service business, or 2) 25% of W-2 wages paid by the non-specified service business, plus 2.5% of the unadjusted basis of the depreciable property owned by the business.

With that in mind, the search is on to see if there is any income from the advisory practice where, with a little flick of the tax-planning magic wand, we can perform some “income alchemy” and turn an advisor’s specified service business income into income derived from a non-specified trade or service business. While there are certainly many possibilities for doing so, some of which, in all likelihood, have not even been thought of yet, the income alchemy strategies most likely to be utilized by advisors would include the following:

Spinning Off, and Then Renting Back, Depreciable Property

While many advisors rent office space or work out of a home office, a substantial number of advisors have purchased the office space out of which they work.

In some instances, the property may be held in the same entity as the actual advisory practice. In other instances, the office space out of which an advisor works and the financial services practice itself may be held in separate entities, but with common ownership.

Given the QBI rules, it will behoove advisors to make sure that office space is owned by a separate entity, and that the advisory business rents that property from the related business (at the highest possible fair market value). Doing so would reduce the amount of specified service business QBI generated from the really-high-income advisor’s practice (as rent is a deductible business expense), while simultaneously increasing the amount of QBI generated from the separate “rental real estate business”, which is not a specified service business.

The end result of the strategy is that the rent the advisor pays on the building would be eligible for the 20% QBI deduction… albeit with a cap of up to 2.5% of the unadjusted basis of the office space, and a higher cap if the rental real estate business also paid W-2 wages for property management or other services (which could potentially be performed by the advisor him/herself!).

Example #1: ABC Advisors is a financial advisory firm organized as an LLC and taxed as a partnership. It is owned 50/50 by two principals, both of whom are well over their applicable QBI deduction phase-out threshold. The income generated by each from the advisory practice is $750,000 per year, none of which is currently eligible for any QBI deduction (by virtue of the phaseout for specified service businesses).

10 years ago, the LLC purchased the office space out of which the advisor firm operates for $1,800,000 in cash. Property taxes, insurance, and other expenses currently amount to $60,000 per year, which do help to reduce the profits of the partnership (thus lowering the principals’ taxable income), but which does little else for tax purposes.

Suppose, however, that ABC Advisors spins out the real estate into a new LLC, XYZ Real Estate, which has identical ownership to ABC Advisors. Further, suppose that ABC Advisors rents the office space from XYZ Real Estate for $150,000 per year. After accounting for the $60,000 of expenses, XYZ Real Estate is left with $90,000 of profit. While their advisor business now has its income reduced by $150,000/year of rent payments (which includes the $60,000 of expenses they would have had anyway, and an additional $90,000 of income that has been shifted from the advisory firm to XYZ Real Estate).

Although the owners of XYZ Real Estate both have income well in excess of the QBI deduction phaseout amount, the rental “business” is NOT a specificed service business, and thus, shifting $150,000 in rent to XYZ Real Estate “saves” a portion of the QBI deduction. Of course, the QBI deduction will be limited by the wages and/or depreciable property test, but while there are no wages, 2.5% of the purchase price of the building is $45,000, which means a potential QBI deduction of as much as $45,000 in total (or $22,500 per partner), though the deduction here would be limited to just $18,000 (20% x $90,000 = $18,000) in total (or $9,000 per partner).

And there are still other ways to potentially improve that deduction amount as well. Consider that while there is $90,000 of QBI generated from the real estate company now, only $45,000 of it is eligible for the QBI deduction (because of the wage/depreciable property limits). As such, XYZ Real Estate might consider hiring a part-time property manager, which would both increase W-2 amounts paid and decrease net profit (QBI) from the business. Of course, increasing expenses would result in less after-tax dollars to the owners viewed in isolation, but perhaps there is a corresponding amount of work currently being performed by someone employed by the advisory practice that can be eliminated (even if the same person is now re-hired by XYZ Real Estate) to keep total costs, across both businesses, the same, while increasing the total amount of income eligible for the QBI deduction.

Also note that in the above example, we imagined that the building originally owned by ABC Advisors was purchased for cash, but in the real world, that is unlikely to be the case. Instead, most likely, just 10 years in, there’d still be some type of mortgage left on the property. While a mortgage does have the added “benefit” of interest, which is generally deductible, that interest expense also reduces qualified business income.

This provides yet even more opportunity for some savvy planning. For instance, instead of transferring the building and the mortgage together, what if prior to spinning off such real estate an advisory firm obtained other financing and used it to pay down the mortgage? Then, afterwards, the advisory firm spun off the now debt-free building into its own LLC, but retained the business loan used to pay off the mortgage on the building on the advisory firm’s books. The end result is that the real estate LLC, unencumbered by debt would produce more QBI (potentially eligible for the QBI deduction, even for owners over the phaseout threshold), while the advisory firm, which would still be responsible for the new line of credit debt, would have its non-QBI deduction eligible (for owners in excess of the phaseout threshold) income reduces by the interest payments on the debt. Plus, as an added bonus, it may be easier to spin out the real estate into its own LLC once the original mortgage is paid off.

Of course, real estate isn’t the only type of depreciable tangible property… it’s just likely the most significant such item for advisors, both in terms of frequency and dollar amount. Nevertheless, advisors who have substantial amounts of other depreciable tangible property may utilize similar approaches.

For instance, suppose an advisory practice interested in improving their custom media decides to make a substantial investment in audio/visual equipment, such as high-performance computers and professional-grade cameras, microphones, soundboards, and lights. These items could be purchased by an entity other than the advisory practice (with common ownership), and then rented back to the advisory practice at fair market value, similar to the structure of renting back the business’ own office space.

The question though, is would all that effort likely be worth it? The answer is probably not. Consider that even if the total cost of all the aforementioned equipment came to $100,000, 2.5% of that amount would be just $2,500, meaning that absent W-2 wages paid by the equipment rental company, the QBI deduction for income attributable to that business would be capped out at $2,500. Even at the highest tax bracket of 37%, that amounts to less than $1,000 of tax savings per year, which would almost certainly be eaten up by additional bookkeeping and tax return preparation costs, not to mention an unnecessary distraction for an already-very-successful advisor (who, at least in part, probably achieved that level of success in the first place by avoiding unnecessary complications like this!).

Which means that while it’s appealing to shift able-to-be-rented tangible depreciable property out of the advisory firm and into a separate entity to pay a fair market rent, in practice for financial advisors it will likely only be relevant for actual office space with a substantive rental value (and a substantive cost basis that leaves ample room for a healthy QBI deduction).

Creating a PEO and Leasing Back Employees

Advisory practices are typically light on capital-intensive physical infrastructure, but are often heavily invested in human capital. In light of the QBI deduction, it may pay to outsource more staffing to a commonly owned professional employer organization (PEO), also known as an employee leasing company. PEOs are not explicitly included on the list of specified service businesses, and thus it appears that QBI derived from such organizations can be eligible for a QBI deduction, even for “really-high-income advisors.”

The concept of, for lack of a better expression, “spinning off” employees and then leasing them back from the PEO is substantially similar to the idea of leasing back tangible depreciable property. Simply put, there will be a fair market rate for the labor purchased by the advisory practice and paid to the PEO. That rate can reasonably be higher than the fair market rate that would be paid if the advisory practice hired that same person directly, to compensate the PEO for the services provided, additional costs incurred, and the risks mitigated by the arrangement (i.e. employment disputes). If things go according to plan, the advisory firm pays the PEO to outsource employment, lowering the QBI generated from the advisory business for which a QBI deduction is not eligible, and the PEO winds up with some amount of profit that is eligible for the QBI deduction. In addition, by virtue of the nature of the PEO business, it will almost certainly pay enough W-2 wages to make the full amount of profit eligible for the QBI deduction.

Example #2: ABC Advisors is a large RIA that employs a variety of persons unrelated to the actual delivery of financial services, including bookkeepers and administrative staff. Cumulatively, these employees earn an aggregate of $500,000 of W-2 wages and benefits per year.

Instead of hiring these employees directly, ABC Advisors could potentially create a commonly owned PEO, hire the above-referenced staff through that entity, and lease those employees back from the PEO. If the PEO charges a reasonable markup for its services (e.g., 30%), the total amount paid to the PEO would be $650,000 ($500,000 expenses + ($500,000 x 30%) = $650,000). Assuming the PEO incurred the same expenses as ABC Advisors to employ the staff, there’d be $150,000 of profit remaining at the end of the year.

Regardless of the owners’ incomes, that amount of PEO net income would be eligible for the QBI deduction by virtue of the fact that the PEO is a non-specified service business (and with more than $300,000 in wages, the 50%-of-wages QBI limit will not be a factor).

Which means if the owners of ABC Advisors (and the newly formed PEO) averaged “just” a 30% marginal bracket, this move would still save the owners a collective $45,000 in taxes… annually (or at least as long as the QBI rules are in effect).

However, in order to avoid likely problems, advisors considering this approach should ensure that they don’t turn the PEO into a financial services company in the eye of the IRS by having PEO employees perform financial services work. In other words, employee financial advisors should not be shifted to the PEO, nor should core investment team staff. Fortunately though, for sizable advisory firms, there are plenty of functions typically performed by employees of advisory firms that don’t amount to financial services, including marketing functions, clerical duties, and other unlicensed administrative support roles.

Licensing Intellectual Property

From time to time, it may be necessary for an advisor’s businesses to have a bit of a facelift or rebranding. Such an exercise may provide for an interesting opportunity for tax planning.

For example, suppose that instead of the advisor’s practice hiring a marketing firm and a graphic designer to create a new brand image, logo, etc., a new company with common ownership is established and takes on this work. Ultimately, the company employs various individuals and pays them a W-2 salary to create a new name, a new logo, marketing slogans, etc.

The new company could then license the intellectual property created back to the advisory practice, perhaps for a percentage of gross revenue. This could further reduce the advisory practice’s QBI, and shift more income to a non-specified service business, for which a QBI deduction may be available.

Example #3: We Stink Advisory Services, LLC, has somehow managed to grow into a $20MM annual revenue RIA, and has decided it needs to undergo a marketing revamp (who’d have thought, eh?).

Instead of doing this work in-house, however, the owners of We Stink Advisory Services, LLC create a new, commonly owned entity, Better Advisor Marketing, LLC. Better Advisor Marketing hires graphic designers, marketers, and other staff (being careful not to hire anyone that would run afoul of the “skill or reputation” clause in IRC Section 199A and result in the new entity becoming a specified service business, itself), who create IP for a new brand, “Awesome Advisors”. We Stink Advisory Services then licenses the Awesome Advisors brand from Better Advisor Marketing LLC for 3% of gross revenues.

The end result? Better Advisor Marketing grosses $600,000 in revenue and We Stink Advisors sees its revenue decline by a corresponding amount. If we assume Better Advisor Marketing paid employees $300,000 of W-2 wages and incurred $150,000 of other expenses (all of which were going to be incurred in the rebranding effort anyway), it would be left with $150,000 in profit, all of which, regardless of the owners’ incomes, would potentially be eligible for the QBI deduction due to the wages paid by the firm ($300,000 x 50% = $150,000 = Better Advisor Marketing profit). At a 30% marginal tax rate for the owners, this results in more than $45,000 in hard-dollar tax savings!

Planning for Advisors In and Around the Phase-Out Ranges

For advisors who are likely to find themselves within the QBI deduction phase-out range, or just over the fully-phased-out mark, strong consideration should be given to finding ways to lower taxable income to actually get under the threshold and claim more of the QBI deduction.

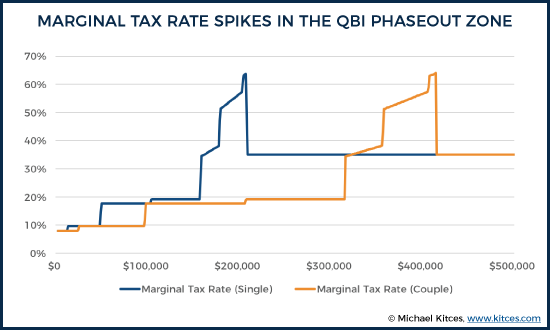

Though minimizing taxable income is often a goal of advisors anyway, it takes on special significance for these individuals, due to the impact that the phaseout of the QBI deduction has on the marginal tax rate itself. In fact, while the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced the top marginal rate for Federal income tax to 37%, in the QBI deduction phase-out range, the real marginal Federal income tax rate for total income within the phase-out range is more than 47%, while the marginal tax rate for pockets of income within the phase-out range can spike as high as 64%!

For instance, the 2018 Federal income tax bill for a married advisor filing a joint return, with $315,000 of QBI and taxable income (before application of the QBI deduction) would be $49,059. The same advisor, with $415,000 of QBI and taxable income (before application of the QBI deduction) would have a Federal income tax bill of $96,629 this year. That’s a $47,570 increase in taxes, and equates to a 47.57% marginal rate on the additional $100,000 of income! And the effect is even worse at the top end of the phaseout range; a couple that had only $414,000 of income would have phased out 99% of their QBI deduction, and had a tax liability of $95,989, which means the last $1,000 of income that increases their tax liability to $96,629 is a $640 tax increase (or a 64% marginal tax rate!).

The reason this rate is so much higher than the top stated rate of 37% is that within the phase-out range, for every additional dollar of income a person earns, they are taxed on that dollar, plus a fraction of an additional dollar due to a phaseout reduction of the QBI deduction. And the more income they earn through the phaseout range, the more QBI deduction there is to phase out in the first place. Put differently, within the phase-out range, for every one dollar of additional income earned, some amount greater than one dollar becomes taxable due to the phaseout of the QBI deduction. This phenomenon is similar to the Social Security “tax torpedo,” a concept with which many advisors are already familiar, and in the past similarly could spike the marginal tax rate as high as 46.25% (for those who were otherwise “just” in the 25% tax bracket).

Given the current tax structure, paying taxes at greater than a 47% rate (or as high as 64% for a brief window of income) is highly inefficient. For advisors that live in states that impose a state income tax, the total proportion of income lost to taxes will be even worse, and it’s likely that more than half of every dollar earned within the phase-out range will not reach the advisor’s pocket. Thus, one must ask themselves, “What can I do to help reduce this tax burden” in this hyper-sensitive QBI phaseout window? Here are just a few ideas…

Consider Going “Halfsies” with Uncle Sam to Invest in Your Business

Thinking about doing a major revamp of your marketing? Considering making your next hire or upgrading the talent at your firm? For a financial advisor hovering around the QBI deduction phase-out range, there’s no time like the present!

Instead of focusing on the fact that for every dollar an advisor earns within QBI deduction phase-out range they will lose, on average, roughly 50 cents to income taxes, advisors should consider reframing the situation and viewing it as an opportunity to have Uncle Sam split the cost of an investment in the advisors business. Because a marginal tax rate of 50%+ on income amounts to a marginal tax rate savings of 50% for every deduction!

In essence, because of the way the QBI deduction works, for every dollar an advisor spends on their business within the phase-out range, the IRS will contribute an additional dollar towards that expense in the form of a tax subsidy!

Example #4: Mark is a financial advisor who files a joint tax return, and who is estimated to have both $415,000 of QBI and taxable income (i.e., he has only a small amount of other income, which is offset by his deductions).

Recently, Mark’s growth has stalled as he’s approached his maximum capacity in the advisory firm. In the past, he’s been reluctant to hire additional help because of the cost, but in light of his current tax situation, now may be the perfect time to take the leap. For instance, suppose Mark hires a CFP® professional to help him manage some of his less complex client relationships. Further imagine that, after salary, employment taxes, and other benefits, the total expense to bring on the new CFP® professional is $100,000. Thus, both Mark’s QBI and his taxable income is reduced to $315,000.

Although Mark has incurred expenses of $100,000 related to his new hire, he will have also seen a drop in his Federal income tax bill of $47,570 due to those expenses. Plus, if we imagine Mark also lives in a state that has a state income tax of 5%, he will have saved an additional $5,000 in state income taxes. The cumulative result here, is that Mark’s hiring expense of $100,000 in additional salary would have “only” cost him a net amount of $47,430 ($100,000 – ($47,570 + $5,000) = $47,430).

This approach, of course, would work well for some advisors, but not at all for others. Sole-proprietor advisors, and 100% owner/employee advisors of S corporations, have the greatest ability greatest opportunity to make decisions like Mark’s. Not only do such advisors have total control over decisions related to expenditures, but every dollar spent at the business level from what would otherwise be profits will reduce the advisor's taxable income by an equivalent (or close to equivalent) amount.

Note: Sole proprietor advisors who spend one dollar on expense will see their net taxable income drop by slightly less than one dollar due to a reduction of the deduction for one half of self-employment taxes. However, for sole proprietor advisors with net business income in excess of the annual maximum amount of earnings subject to Social Security taxes ($128,400 for 2018), the reduction of the self-employment tax deduction is fairly negligible.

By contrast, for advisors who are engaged in partnerships, or for those engaged in larger S corporation practices, the “strategy” of spending as outlined above will generally not work as well. To begin with, such advisors may not have substantial control over the decision-making process. Even in situations where the advisor does have control, however, there are other issues. For instance, if an advisor is a 50/50 owner of an S corporation with another advisor, for every dollar of what would otherwise be profit spent at the entity level, each advisor’s income will be reduced by 50 cents. If both advisors find themselves within the QBI deduction phase-out range, they may be equally interested in making the additional business investments. However, if one advisor’s taxable income is substantially below or above the phase-out range, they may be far less interested in spending those dollars (because each dollar spent will potentially “cost” them much more).

In other words, because the QBI deduction and phaseout itself is calculated one owner at a time (using qualified business income but based on their personal tax return), it’s entirely possible that one partner will be in the phaseout zone but the other will not, which means the relative benefit (and tax savings subsidy) of additional hiring may be very different from one partner to the next.

Reduce Income By Reducing Workload

Advisors who find themselves in or just over the QBI deduction phase-out range may simply wish to reevaluate life and priorities. “Does it pay to reduce my workload and income in order to spend more time doing other things?” It’s a fair question an advisor may wish to ask him/herself.

The question really boils down to this… does the marginal benefit of the additional income warrant the marginal time and/or effort it takes to produce that income? Again, consider that within the QBI deduction phase-out range, the average marginal tax rate is close to 50% and can briefly rise as high as 64%. Thus, the reduction of income for advisors within this range will cost them less net dollars than any other situation they are in which they are likely to find themselves. Or alternatively, they may simply decide not to work as hard when they’re only keeping less than 50 cents on the dollar!

Example #5: Shana is a financial advisor who files a joint tax return, and who is estimated to have both $415,000 of QBI and taxable income. Her practice consists of roughly 100 families. The “top” 60 families generate $315,000 of Shana’s business income (and therefore QBI), while the “bottom” 40 families generate $100,000 (of QBI).

One option Shana might consider here is shedding her bottom 40 clients in order to reduce her income by $100,000. By doing so, and by eliminating some 40% of her household relationships, Shana would substantially reduce her workload, all while decreasing her after-tax income by just $52,430, or roughly 16%. Unless Shana really needs that additional income, the trade-off of “just” ~16% of after-tax in exchange for perhaps a third of her time back might be well worth it.

Ultimately, for advisors like Shana, the decision of what to do will largely come down to priorities and long-term goals. If, for instance, Shana is interested in further growing her practice and her income, than jettisoning over one-third of her client base may not be the right move (at least when it comes to taxes). At some point, if Shana does continue to grow her practice, she’d have to do her best Jim Morrison impression and “break on through, to the other side” of the phase-out range, so it might as well be now. After all, the flip side of pushing through the artificially high marginal tax rate within the QBI deduction phase-out means that, going forward, future income will almost always be at a lower rate. In other words, the worst will already be behind Shana, perhaps increasing her incentive to further expand the business? After all, once the QBI deduction is phased out, Shana is “just” in the 35% ordinary income tax bracket.

Alternatively, maybe Shana’s long-term goals are less grand from an income/business size perspective, and instead, focus more on quality of life and time outside of work… what many today refer to as a “lifestyle practice.” If so, there may be no greater delta in the ratio of time back/after-tax income foregone than the approach outlined above.

Condense Lifetime Giving (With A Donor-Advised Fund?)

Many advisors are charitably inclined and support various causes with both time and money. For such advisors, particularly those who are within or just above the QBI deduction phase-out threshold and who lack the flexibility or desire to increase expenses (and who don’t wish to reduce their top-line revenue), one idea is to bulk up on charitable contributions.

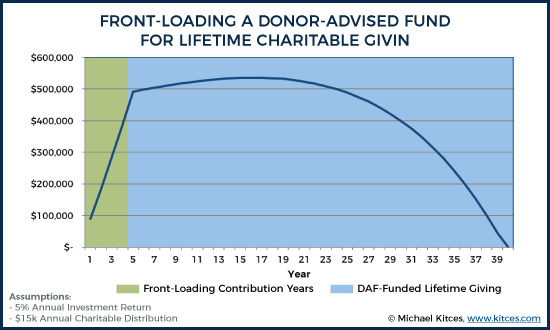

After all, unlike most other phase-out thresholds in the tax code - which are typically tied to AGI (or some derivative thereof) – the QBI deduction is tied to taxable income, which means advisors can increase their potential QBI deduction by increasing below-the-line, itemized deductions like charitable contributions. Furthermore, the availability of certain charitable planning vehicles, such as donor-advised funds, means that such advisors can accelerate charitable contributions now for maximum tax efficiency, but use those funds to support their charitable desires for years to come.

Example #6: Evan is a financial advisor who files a joint tax return, and who is estimated to have both $415,000 of QBI and taxable income. He and his family are charitably inclined, and typically donate about $15,000 to year to various organizations. Suppose, however, that Evan decides, instead of donating his typical amount to charity, to contribute an extra $100,000 to a donor-advised fund in order to receive an additional $100,000 itemized deduction, which reduces the net cost of his $100,000/year charitable gifts to barely $50,000/year instead.

Let’s further assume that Evan does the same thing for the next 5 years, bringing the total contributions to his donor-advised funds to $500,000 over that time.

If we assume that Evan is able to earn 5% per year on the amounts invested in his donor-advised funds, he would be able to distribute annual amounts of $15,000, adjusted for inflation, for nearly 40 years. That may very well cover Evan’s charitable intent for the rest of his life!

The beauty of this idea is not merely the general value of getting tax-free growth on future charitable giving with a donor-advised fund, but the tax leverage of doing so within the QBI phaseout zone. As due to the high average marginal tax rate within the QBI deduction phase-out range, it would almost be like Evan was “only” making annual contributions of roughly $50,000 to the donor-advised fund, but was being matched dollar-for-dollar on his contributions by the IRS! Put differently, Evan might ask himself this… “Would I rather give the IRS $47,570 and keep $52,430, or put all $100,000 towards satisfying my long-term charitable-giving goals?” For some, this will be an easy choice.

Increase Contributions to Retirement Plans To Reduce QBI Phaseout

While all of the approaches outlined above would result in an advisor increasing their QBI deduction, they also have one other thing in common… they all result in less net dollars in the advisor’s pocket (as giving away 100 cents to a charity is still less wealth than paying 50 cents on the dollar in taxes and at least keeping the 50 cents left over). That may be okay for some advisors, but despite the relatively high phase-out ranges for the QBI deduction, other advisors may not feel comfortable with, be able to, or have a desire to part with that (albeit limited and highly taxed) net income. In such instances, a logical approach is to try and keep the income, but to “switch pockets” by placing more of it into tax-deductible retirement accounts. The result is that income is not actually “lost” as it is in the other scenarios discussed above, but rather, it is merely deferred (at a highly favorable marginal tax rate!).

This approach may be limited for some advisors, though. For instance, many high-income advisors already “max-out” contributions to their 401(k) or other employer-sponsored retirement plan. Thus, these advisors may only be able to shift more money into retirement plans by layering an additional retirement plan, such as a cash balance plan, pension plan, or non-qualified deferred compensation plan, on top of the existing 401(k) (or similar plan). Or perhaps by hiring a spouse (or other family member) to perform bona fide work, in order to shift income, and allow for increased cumulative family contributions to retirement accounts.

And advisors who are part of ensemble-or-larger practices may have little to no say over the available retirement plan options. Thus, it may be impossible for these advisors to increase their own contributions to a retirement plan. And adding in a retirement plan for a multi-advisor (and especially multi-employee) firm may have other costs, both administratively to run and manage the retirement plan, and with respect to required or expected contributions to other partners and employees (e.g., matching or safe harbor profit-sharing contributions). Similarly, such advisors are less likely to be able to unilaterally hire family members in order to shift portions of the income they would otherwise be entitled to receive.

Nonetheless, the point remains that one of the most appealing ways to truly maximize wealth in the QBI phaseout zone is to “keep” the dollars, and simply shift them to a more tax-preferenced way of accumulated them, such as via paid family members for bona fide services to the business, or into qualified employer retirement plans.

Final Thoughts

The fundamental point of the limitations on the QBI rules was to avoid turning “labor” income for high-income professionals into tax-preferenced business income, as the stated goal of creating the QBI deduction was to stimulate job growth (not merely to reduce the tax burden of high-income professionals).

However, in practice, as advisory firms grow, their income is less a function of the owner themselves, and more the results of their investments in (human) capital, not unlike any other factory or service business. Arguably, then, a financial advisory practice that employs 10 people should be treated similarly to an architectural firm that employs 10 people, or a landscaping business with 10 employees, or a factory that has 10 employees? Is the financial advisory firm doing any less for the families of those 10 employees? These are questions that I’ve been asked repeatedly by advisors throughout the country since the QBI deduction was created. They’re fair questions, but frankly, they don’t really matter. The law is, what it is... until it isn’t anymore.

All is not lost for high-income financial service professionals though. Despite being labeled as a specified service business, those with more “modest” incomes will still be able to enjoy QBI deductions. Other, higher income advisors who are closer to the phaseout zones will be able to make personal and/or business decisions that will lower their income and make them at least partially eligible, too. Still others will venture down more creative routes, and try to turn QBI-ineligible advisory practice income into qualified business income from another entity, though admittedly, there is at least some risk in undertaking these strategies prior to the release of IRS regulations and/or other guidance (which is anticipated within the next month or so). Nevertheless, while there is much left to learn about how the IRS will treat various aspects of the QBI deduction, there is no time like the present for advisors to analyze their own situation and begin making efforts to secure the largest feasible QBI deduction!

So what do you think? What strategies are you considering for income in and around the QBI phaseout range? How are you talking to other small business owner clients who could be impacted by the QBI phaseout? Should advisors be treated differently than owners of an architectural firm? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply