Executive Summary

Setting a proper time horizon is a crucial step in planning for retirement, and is typically done by making a reasonably conservative estimate of life expectancy... perhaps with a few extra years for padding, depending on a client's preferences.

Yet in many cases, planners adopt a uniform "standard" assumption for clients, without adapting it to even the most basic client circumstances, like whether the client is a single person or a married couple, despite the material difference between individual and joint life expectancies. Similarly, while the reality is that there's a high likelihood that a married couple will live several decades in retirement, the odds are overwhelming that for much of that time period, only one - but not both - of them will be alive.

As a result, it may be time for planners to begin to adopt more nuanced life expectancy assumptions for clients, at a minimum making a distinction between individuals and married couples, and with reductions in the later years for married couples to acknowledge the fact that while it's likely one may be alive, it's very unlikely that both will live through the entire time horizon. Otherwise, simply choosing an arbitrarily long time horizon for clients, paired with a high standard of Monte Carlo success, may actually result in an unnecessarily constrained retirement lifestyle!

Life Expectancy Planning For Singles Vs Couples

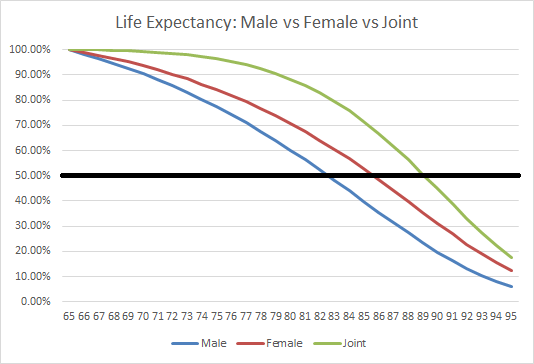

While the "default" retirement assumption is often based on a married couple, the reality is that often planning involves a single individual, whether unmarried or a widow. Yet the reality is that the "typical" retirement assumption of a 30-year time horizon at age 65 looks drastically different in the context of a married couple versus a single person, as shown in the chart below:

The black horizontal line represents the 50th percentile for survival (or what we commonly call "life expectancy"), which is approximately age 89 for the starting-age-65 couple (based on the Social Security Administration's 2007 Period Life Table). Notably, though, it's only age 85 for a 65-year-old female, and age 82 for a 65-year-old single male. This is not a trivial difference; the life expectancy for a single person is 4-7 years shorter than for a married couple, and it's only 24 years in the first place for a 65-year-old married couple. In other words, the life expectancy when planning for individuals is 15%-30% shorter, which - if properly adjusted - would allow for a significant increase in retirement spending!

Of course, many planners don't like to use life expectancy alone as a basis for planning - after all, by definition half the clients will live longer - which is why age 95 is not uncommon as a final retirement age for a married couple. Yet here, again, the difference between couples and singles is notable; there is only a 12% chance for the single female to still be alive, and a 6% chance for the single male, but a (comparatively) whopping 18% chance that at least one member of the couple is alive at age 95.

A Deeper Look At Joint Life Expectancies

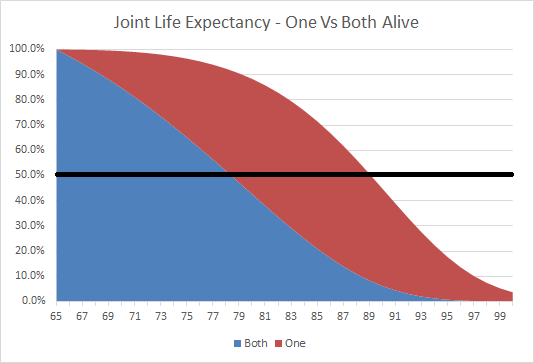

As just noted, the joint life expectancy for a 65-year-old couple is age 89, though by age 95 the survival probability rapidly falls from 50% to only 18%. However, it's important to bear in mind that the life expectancy survival probabilities for a married couple are based on the likely that they're not both deceased - or viewed another way, the couple can meet the condition of "still alive" as long as one, the other, or both are alive.

When viewed in component parts, though, this distinction between the probability that only one member of the couple is alive, versus both are alive, is significant, as shown in the chart below:

Once again, the black horizontal line represents the 50th percentile. While the "stacked" probability of having both or one alive once again confirms the age 89 life expectancy of the couple, the startling reality is that the 50th percentile of having both alive is only age 78! In fact, at age 89, while there may be a 50% probability that at least one member of the couple is alive, the odds are only about 8% that it's both of them and a whopping 42% that it's one - and only one - of them still alive.

For those who "conservatively" plan for a longer time horizon, again there is an 18% probability that at least one member of the couple is still alive at age 95. However, that's based on a probability of about 17% that only one of them is alive, and a less-than-1% chance that both of them are still alive!

Practical Financial Planning Implications

The practical implications of these life expectancy probability charts are relatively straightforward - that routinely planning for all 65-year-old clients to live for 30 years to age 95 may actually be remarkably conservative, and possibly too conservative.

Granted, it's worth noting that the Social Security Administration's Period Life tables are only one of several commonly used life expectancy tables, which also include the U.S. Life Tables from the U.S. Census and the Annuity 2000 tables from the Society of Actuaries, both of which tend to assume slightly greater longevity. And for those who are optimistic on the impact of advances in medical technologies, none of the tables may necessarily fully account for how life expectancy could change in the future (on the other hand, it's not clear whether today's retirees may live long enough to witness a material change in the life expectancy for seniors).

Nonetheless, the point remains that, to the extent planners do choose "some" baseline as a planning time horizon for married couples, arguably a distinctly different - and shorter - time horizon should be used when planning for a single individual. To use the same arbitrary planning time horizon for individuals and married couples belies the material differences in longevity that exist.

In addition, the reality remains that there is an even more significant difference between the probability that one member of a couple remains alive, versus the probability that both remain alive, despite the fact that a "joint life expectancy" inherently includes both. When evaluated based on the component parts, it becomes clear that even for planners who wish to make a conservative longevity assumption, proper planning should include a material time period where only one member of the couple is alive, with spending adjusted accordingly.

Of course, given that some household expenses are fixed, the death of one member of the couple doesn't necessarily mean that spending falls by 50%; nonetheless, baseline spending when just one member of a married couple is alive is clearly some amount materially lower than when both are alive (not to mention how spending may simply decline in later years as lifestyle slows down as well). Either way, between lifestyle declines and the death of one spouse, it seems difficult to justify not making a material reduction real spending in the final years of a retirement projection for a married couple.

An alternative solution to deal with this challenge is to do Monte Carlo retirement projections assuming "stochastic" life expectancy - in other words, in every trial of the retirement plan with various dynamic probability-based random returns, also use dynamic probability-based life expectancy. From a practical perspective, not all financial planning and Monte Carlo software can do this, though. In addition, the reality is that if life expectancy is modeled with randomness, recommended spending levels may actually be slightly higher than just arbitrarily assuming a long time horizon past life expectancy; after all, with stochastic life expectancy, sometimes a client's "irresponsibly high" spending behaviors will be justified by a "bad luck" early death. On the other hand, this is also an implicit acknowledgement that assuming an arbitrarily fixed long time horizon, plus requiring a high probability of success, can actually result in an ultra-extreme-conservative retirement projection that may unnecessarily constrain retirement spending to protect against miniscule risks.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: when setting a time horizon for a retirement plan, there should be differences in the planning assumptions for single individuals versus married couples. In addition, it's crucial to recognize that while there is a high likelihood that at least one member of a couple lives for several decades in retirement, the odds are also very high that it will be only one of them for much of that time period - not both - so be certain to plan and adjust projected retirement expenses accordingly! And of course, if individual client circumstances dictate, you may want to make further client-specific life expectancy adjustments as well!