Executive Summary

While there are many tax and investment benefits to investing directly in real estate, not everyone wants to be a hands-on landlord. For those who buy a substantial amount of real estate, it’s often cost effective to hire a property manager to delegate such management tasks to. For everyone else, the most appealing option is simply to become a “pooled” real estate investor with others, through a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT), which allows some of the pass-through tax benefits of real estate investing, but with better management economies of scale and more diversification than what most investors can feasibly access with limited dollar amounts to invest.

Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, though, REITs have been afforded a new tax preference: the IRC Section 199A deduction for “pass-through” businesses, that allows for a 20% deduction of any qualified REIT dividends against that very income, resulting in an effective 20% reduction in the tax rate on REITs (where the top 37% tax rate becomes “just” 29.6% instead).

Notably, the new Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction under Section 199A is available for direct investments in real estate as well. However, direct real estate investments only qualify for the deduction if the amount of real estate investment activity amounts to a real estate “business” (where purely passive real estate investment income may not count), and is further limited for certain high-income individuals due to wage-and-depreciable-property tests that apply to married couples with taxable income above $315,000, and all other filers with taxable income about $157,500. By contrast, qualified REIT dividends simply obtain the 20% Section 199A deduction, implicitly counting as a real estate “business” (by virtue of a REIT’s size and scale), and without any high-income limitations on the deduction!

Of course, in the end, an investment in a REIT should be evaluated by its overall investment merits, and not just its tax treatment alone. Nonetheless, for otherwise equal real estate investments, going forward, REITs will be substantially easier to qualify for the full Section 199A deduction with fewer limitations for high-income individuals, and a tax benefit sizable enough that REITs almost (but not quite) enjoy tax benefits similar to the preferences for long-term capital gains and qualified dividends. Which means at a minimum, the relative improvement of tax treatment for REITs will mean they deserve a “fresh look” from an investment perspective… along with a re-evaluation of where they should be held from an asset location perspective (given that REITs held in a tax-preferenced retirement account will lose out on the new Section 199A deduction!).

Application of the 20% QBI Deduction to Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs)

One of the most common ways individuals invest in real estate is through real estate investment trusts (REITs). REITs were established in 1960, when then-President Eisenhower signed into law the Cigar Excise Tax Extension, and are companies that receive special tax treatment: specifically, REITs don’t pay any income tax at the entity level despite being a corporate entity, and simply pass through their income to be taxed to the shareholders.

In exchange for their favorable tax treatment, REITs must follow certain rules outlined under IRC Section 856. These rules include requirements for REITs to have at least 100 shareholders after the entity’s first year as a REIT (which eliminates the ability for investors to create “personal REITs” to hold their own real estate), at least 75% of total assets must be invested in real estate assets and cash, and at least 75% of gross income must be derived from real estate-related sources (such as rental income and interest on mortgages). REITs are also required to distribute at least 90% of their taxable income annually as dividends, which makes them a popular component of many income-focused portfolios.

Yet while REITs have always enjoyed favorable tax treatment, with the passing of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the already-preferred tax treatment of REITs has been further enhanced.

Because under IRC Section 199A of the new tax law, REIT owners are generally eligible for a deduction equal to 20% of their “qualified REIT dividends” (as a part of the rules for Qualified Business Income or QBI). Qualified REIT dividends are defined as any dividends from REITs that are not capital gains dividends (e.g., because the REIT sold its underlying real estate properties and generated a capital gain as defined in IRC Section 857(b)(3)), and are not qualified dividend income (for any non-REIT income that is distributed as a dividend as defined in IRC Section 1(h)(11); in other words, most “normal” REIT income distributions are eligible for the Section 199A deduction.

The end result is that, when the QBI deduction allows 20% of the REIT’s income to be deducted against itself, the investor only pays taxes at 80% of the “normal” ordinary income rate. Thus, the 10% tax bracket on REITs is really only taxed at 8%, and an investor in the top 37% tax bracket on their REIT income pays at only a 29.6% rate (as with $1,000,000 of REIT dividends, only $800,000 are taxed after the Section 199A deduction, and 37% on the $800,000 net is the equivalent of 29.6% on the original $1,000,000 of REIT dividends).

Qualified REIT Dividends Must Be Netted Against Qualified Publicly Traded Partnership (PTP) Income

In most instances, the application of the Section 199A deduction to qualified REIT dividends will be fairly straightforward – simply subtract 20% of the REIT dividend income as a deduction on the tax return. There are, however, a number of wrinkles that could complicate matters in certain situations.

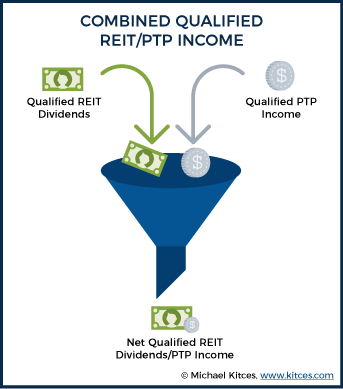

One such wrinkle is that, prior to the application of the 20% deduction, an investor’s qualified REIT dividends must be netted against his or her qualified publicly traded partnership (PTP) income (e.g., from Master Limited Partnerships [MLPs]). In general, the 20% QBI deduction is then applied to that net amount.

The reason is that, while an investor can’t really have negative qualified REIT dividends (though the term “negative dividend” has occasionally been used to describe a variety of situations, the term has been used euphemistically, and none of the situations have actually been negative dividends), it is not uncommon for publicly traded partnerships to have negative net income.

Master limited partnerships (MLPs) for instance – probably the most common PTP in investors’ portfolios – often have negative ordinary business income (indicated by a negative number in Box 1 of the Schedule K-1), even if the MLP made “income” distributions throughout the year (due to substantial depreciation deductions within the MLP that more than offset the taxable income distributions). As such, in instances where clients own both REITs and PTPs, negative qualified PTP income may reduce, or eliminate, any QBI deduction that would have otherwise been available for the qualified REIT dividends.

Example #1: Samantha has a large position in REITs and generates $50,000 of qualified REIT dividends. As such, she would generally be entitled to a $10,000 ($50,000 x 20% = $10,000) QBI deduction.

Suppose, however, that Samantha also had a sizeable investment in various PTPs, which when disposed of, produced a cumulative $50,000 tax loss in 2018 (even though she received $30,000 of cash distributions from the MLP throughout the year). In such an instance, the $50,000 of qualified REIT dividends will be completely offset by the negative $50,000 of qualified PTP income, and Samantha will receive no QBI deduction.

Qualified Business Income (QBI) Losses Are NOT Netted Against Qualified REIT Dividends

A key aspect of the QBI deduction, in general, is that it is only permitted against net qualified business income across all applicable businesses eligible for the deduction. Thus, the losses from one QBI-eligible business must be netted against the gains of another, which means that while the losses do net for income tax purposes (good news for reducing the total tax liability), they also net for the purposes of the QBI deduction (bad news as it can reduce or eliminate the QBI deduction altogether).

In this context, it’s notable that, although REIT dividends are included in what is known as the “combined qualified business income amount,” and are generally eligible for the Section 199A deduction, they are not actually considered QBI. Instead, to be QBI, income must be derived from an individual’s trade or business. IRC Section 199A(c)(1) explicitly makes this point, and reads as follows:

“The term ‘qualified business income’ means, for any taxable year, the net amount of qualified items of income, gain, deduction, and loss with respect to any qualified trade or business of the taxpayer. Such term shall not include any qualified REIT dividends, qualified cooperative dividends, or qualified publicly traded partnership income.” (emphasis added)

Fortunately, Section 199A does go on to still permit qualified REIT dividends to be eligible for the deduction anyway, by stating in IRC Section 199A(b)(1) that “combined qualified business income amounts” means:

“The sum of the amounts determined… for each qualified trade or business carried on by the taxpayer [after application of relevant phaseout limitations], plus 20% of the aggregate amount of the qualified REIT dividends and qualified publicly traded partnership income of the taxpayer.” (emphasis added)

Thus, technically, qualified REIT dividends aren’t “QBI income,” per se, but separate income that is also eligible for the Section 199A QBI deduction.

This distinction, which may at first seem trivial, is actually of significant importance due to the way that losses are (and aren’t) netted across QBI and other/combined qualified REIT dividends/PTP income.

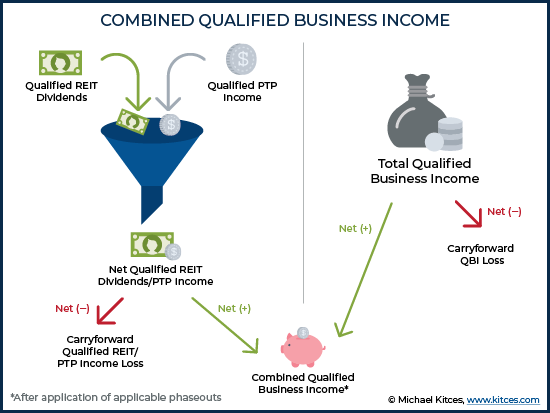

Specifically, it means that while qualified REIT dividends and qualified PTP income are netted against one another prior to the application of the QBI deduction, if the combined amount results in a loss, the REIT/PTP loss is not netted against any positive QBI. Instead, the REIT/PTP loss is carried forward to future years, and will only be used to offset future qualified REIT dividends or PTP income (but not future QBI).

Similarly, if an investor has negative QBI, that amount is not netted against any positive amount of qualified REIT dividends/PTP income that would otherwise be eligible for the QBI deduction. In such an instance, the negative QBI would result in a carryforward loss, and will only be used to offset future QBI, even as the 199A deduction is still claimed against the REIT and PTP income.

In other words, the calculation of the QBI deduction for qualified REIT dividends/PTP income and the calculation of the QBI deduction for QBI, itself are generally parallel calculations but do not actually impact or limit one another. Instead, as affirmed by recently proposed Treasury Regulations on Section 199A, in any year where a loss occurs, the negative amount is treated as $0 for the purposes of calculating combined qualified business income, and any actual loss is then carried forward to the subsequent year.

Example #2: Ralph and Teri have taxable income, prior to the application of the QBI deduction, of $200,000 for 2018. Their income includes no capital gains, but does include $40,000 of qualified REIT dividends.

Early in 2018, Teri started a new, sole proprietorship business, which ran a $20,000 loss for the year (creating negative $20,000 of QBI).

Based on these facts, Ralph and Teri would receive an $8,000 ($40,000 x 20% = $8,000) Section 199A deduction for their qualified REIT dividends. Their negative QBI of $20,000 is not netted against their $40,000 of qualified REIT dividends, and instead is still treated as $40,000 (qualified REIT dividends) + $0 (negative QBI income) = $40,000 x 20% = $8,000.

In the meantime, the actual net QBI loss of $20,000 is carried forward (which will offset QBI income and the associated deduction from Teri’s business in future years if/when she generates positive QBI).

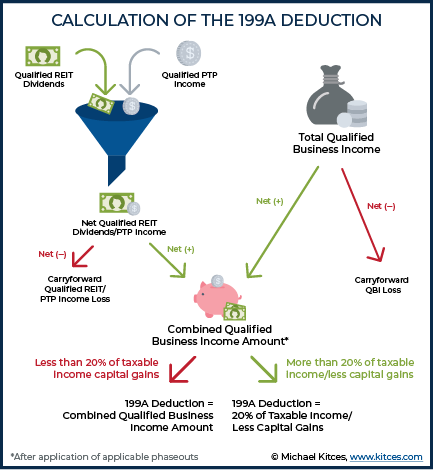

The “Combined Qualified Business Income Amount” And The Taxable Income Limitation On QBI Deductions

As noted above, while the net amount of qualified REIT dividends/PTP income is not considered QBI, it is included in what’s known as the “combined qualified business income amount.”

An individual’s combined qualified business income amount is the sum of their deductions for all QBI after the application of relevant QBI deduction limitations (i.e. the 50%-of-W2-wages or 25%-of-W2-wages-plus-2.5%-of-the-unadjusted-basis-of-depreciable-property tests that apply above $315,000 of taxable income for married couples, and $157,500 of taxable income for all other filers), plus 20% of the net amount of qualified REIT dividends/PTP income. This sum is then further limited to 20% of the taxpayer’s overall taxable income (less net capital gains) if lower.

Example #3: Erin is the owner of a hardware store. After applying the wages and wage-and-depreciable-property tests, Erin calculates a $13,000 deduction attributable to her QBI. Erin also has $30,000 of qualified REIT dividends, potentially entitling her to an additional $6,000 ($30,000 x 20% = $6,000) deduction. Thus, Erin’s combined qualified business income amount is $13,000 + $6,000 = $19,000.

However, if Erin’s total taxable income were only $80,000, then her QBI deduction would be limited to $80,000 (taxable income) x 20% = $16,000, instead of the full $19,000 amount.

Benefits of REITs Over Direct Real Estate Under The 199A Deduction

Real estate is an integral part of many investors’ portfolios, but there are a variety of ways in which investors can gain access to this asset class, and each way offers unique advantages and disadvantages. Oftentimes, owning real estate directly (buying a property outright, or via an LLC or similar-owned entity) offers the most attractive tax treatment, as depreciation deductions frequently allow investors to reduce their taxable income and/or offset other passive income during the initial years of ownership. In contrast, depreciation is still claimed internally within REITs and may reduce the tax implications of their dividends, but it cannot produce negative income (a potentially tax-deductible loss) that nets against other property.

Yet, thanks to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, REITs have picked up a significant new tax edge over directly-owned real estate, particularly for high-income clients.

The distinction is that when an individual owns real estate directly and the activity qualifies as a trade or business, that individual is generally eligible for a 20% QBI deduction on the profits from the real estate business… but once a real estate owner’s income exceeds their applicable threshold ($315,000 for married couple’s filing joint returns, $157,500 for all others), they may begin to have the portion of their Section 199A deduction attributable to real estate-related QBI phased out (due to the 50%-of-W2-wages and 25%-of-W2-wages-plus-2.5%-of-the-unadjusted-basis-of-depreciable-property tests).

By contrast, the Section 199A deduction for qualified REIT dividends (netted with qualified PTP income) is not constrained by the income-based QBI deduction limitations (the wages or wage-and-property tests). As a result, even for a high-income taxpayer, the full amount of the Section 199A deduction for qualified REIT dividends (and PTP income), even if all of their other QBI deductions have been phased down to a reduced amount (or eliminated entirely) as a result of the wages or wage-and-depreciable-property tests! Thus, at least for some high-income taxpayers, REITs may offer more favorable tax treatment than would be obtained via direct-owned real estate (in situations where the wage-and-property tests may have otherwise come to bear).

In addition, the QBI deduction for real estate investing isn’t even permitted for those who “just” hold direct real estate as investments and not as a business (e.g., when just holding a single passive property, or investing into triple net lease properties). By contrast, even a “passive” investment into a REIT will be fully eligible for the Section 199A deduction, regardless of the investor’s own individual level of activity and engagement in the business (or not)!

Revisiting The Asset Location Of REITs With Their 199A QBI Deduction

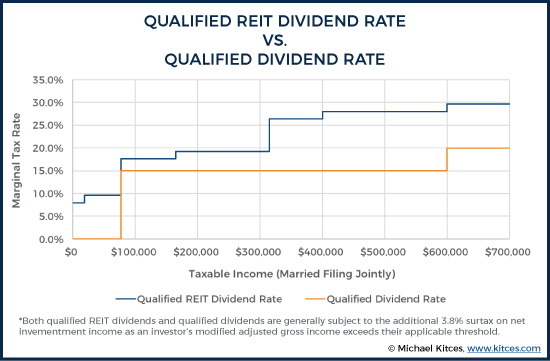

It is worth noting that the Section 199A deduction on REITs also helps close the gap between the tax rates investors will generally pay on qualified REIT dividends, as opposed to “regular” qualified dividends (which qualify for long-term capital gains).

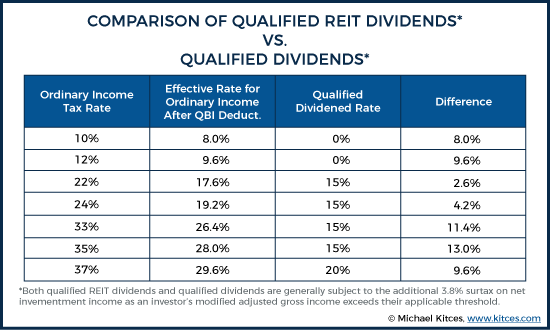

For instance, as noted in the chart below, for investors in the 22% ordinary income tax bracket, the QBI deduction narrows the difference between the tax rate that would be paid on qualified REIT dividends and a “regular” qualified dividend on other income-producing stocks to just a 2.6% rate differential.

The increased tax efficiency of REIT dividends in comparison to previous years means not only taking a fresh look at the relative value of REITs to other income-producing assets (from bonds to dividend-paying stocks) but also makes revisiting an investor’s REIT asset location a must. Specifically, as a result of the Section 199A deduction, it is now more preferable to hold REITs in taxable accounts than in prior years (as the QBI deduction is lost if the REITs are held in a tax-deferred account). Notably though, depending on an investor’s asset mix, and the yield and turnover of other investments within the total portfolio, the optimal location for an investor’s REITs may still be their IRA, Roth IRAs or other tax-preferred accounts.

Ultimately, the purpose of the Section 199A deduction for pass-through business income was not specifically to incentivize REITs (or real estate investments in general). Nonetheless, the fact that the 20% deduction does apply to real estate investing provides a material new tax benefit for doing so. And the fact that (qualified) REIT dividends can qualify for the Section 199A deduction far more easily than direct real estate investing – due to the lack of potential high-income limitations on the deduction, and the implicit fact that REITs automatically meet the “real estate trade or business” requirement as a real estate investor – suddenly makes REITs far more compelling from a tax perspective than they were in the past… even if their treatment doesn’t quite amount to the tax preferences still available for long-term capital gains and qualified dividends.

Leave a Reply