Executive Summary

In its latest update, Fidelity recently estimated that the average 65-year-old couple will need a whopping $280,000 just to cover their health care costs in retirement, between Medicare Part B and Part D premiums, and additional out-of-pocket costs (or the Medigap supplemental insurance plan to mitigate them). Not including the potential cost of long-term care needs as well. As a result, one recent study of prospective retirees found that more Baby Boomers are actually less afraid of running out of money in retirement than they are specifically fearful of handling health care costs in retirement.

Yet the reality is that health care costs in retirement aren’t needed as a “lump sum” on the day of retirement, and the Medicare system actually makes health care costs a remarkably stable annual cost that can be planned for. And in fact, looking at health care expense in retirement as a lump sum masks a number of more direct and substantive planning issues, from the fact that unhealthy retirees may face fewer years of costs but much higher annual costs, to the challenges (and additional costs) of navigating health insurance as an early retiree via state health insurance exchanges.

Accordingly, a recent joint study by Vanguard and Mercer Health and Benefits analyzed the typical (and potentially unexpected) costs of health care in retirement, and showed that the "scary" lump sum cost of retiree health care is actually little more than spending a few hundred dollars per month, per person… for the better part of 2-3 decades in retirement, with the average female spending just $5,200/year throughout her retired years including all health care-related costs (albeit excluding long-term care needs).

Of course, individual health care costs may still vary… but it turns out they vary in rather predictable and plannable ways, from the increase in health care costs for those entering retirement with one or several chronic health conditions, to those who must plan for the additional costs of health insurance via state marketplaces for early retirement, and the additional layer of costs for high-income individuals due to the Medicare income-related surcharges.

Which means in the end, while health care costs may cumulatively add up to a lot over a multi-decade time horizon, they do so in ways that can be largely planned for in advance, saved for with both retirement savings itself or using Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) as a supplemental retirement savings vehicle, managed by making good Medicare enrollment choices, and adjusted for (typically-known-by-retirement) chronic health conditions. Or simply funded by Social Security payments, which for a married 65-year-old couple earning merely “average” benefits, amounts to a lump sum equivalent of more than $600,000 anyway (for those who prefer to convert ongoing retirement cash flows to lump sum equivalents)!

Projecting Annual Health Care Expenses In Retirement And The Absurdity Of Lump Sum Estimates

Despite a steady drumbeat of media coverage that Baby Boomers aren’t saving enough for retirement, a recent PwC survey of Boomers found that their biggest fear about retirement isn’t actually running out of money before the end of retirement. It’s how they’re going to handle their health care costs in retirement.

The fear isn’t necessarily surprising, given annual studies showing what a substantial cost health care expenses in retirement can be. A recent study by the Employee Benefits Research Institute (EBRI) found that a couple retiring today needs a whopping $273,000 to have a 90% chance of covering their health care costs in retirement, including Medicare, Medigap supplemental insurance coverage, and out-of-pocket spending (from prescription drug co-pays to hospital coinsurance). Fidelity has similarly estimated the cost at $280,000. And these estimates are just for medical expenses for ongoing health care in retirement and exclude potential costs for long-term care.

Yet while these dollar amounts may seem like eye-popping “big” numbers – especially in a world where a recent TransAmerica study found the average Baby Boomer has just $147,000 saved for retirement to begin with – the reality is that retiree health expenses aren’t actually needed all at once upon retiring in the first place. In fact, it turns out that the typical savings requirements for retiree health care costs are really little more than a moderate ongoing annual dollar amount… spent repeatedly over a long multi-decade period of time.

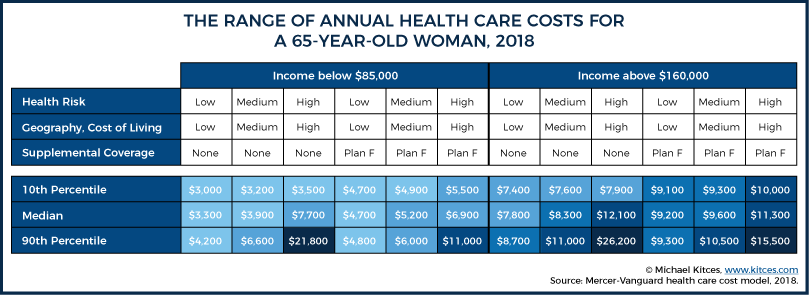

For instance, a recent joint study between Vanguard and Mercer Health and Benefits on planning for retiree health care costs found that for a typical 65-year-old woman, the median annual health care expense in retirement is “just” $5,200/year. Of course, that expense may continue for 20+ years – adding up to more than $100,000, plus ongoing health care inflation at a rate above the general level of inflation – and for a married couple, a spouse may incur another $5,000+/year between $1,600/year in Medicare Part B premiums, $600/year in Part D prescription drug coverage, another $1,700/year in comprehensive Medigap Part F, and $1,100+ annually in various out-of-pocket costs.

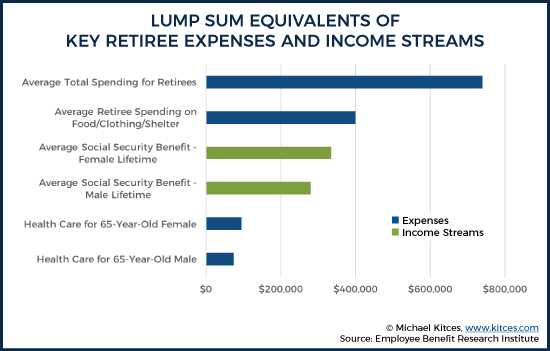

Yet ultimately, recognizing that health care costs may be “just” about $5,000/year per person (or $10,000/year for a couple) for 20+ years of retirement is not necessarily as daunting as a $273,000+ lump sum obligation for retiree health care costs! After all, as the recent Vanguard/Mercer study notes, the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey data estimates that the average individual over age 65 spends $16,903/year on food, clothing, and shelter in retirement… but we don’t typically report this as a $400,000 lump sum obligation at retirement. And in fact, BLS data shows that total spending over age 65 in all categories is nearly $31,000/year… which, again, isn’t typically reported as a $740,000 lump sum requirement for retirement.

Similarly, most retirees don’t look at their income streams in retirement as lump sum assets, either. Yet the “lump sum” value of the average $1,294/month Social Security benefit is nearly $280,000 for males and $335,000 for females (over $600,000 as a married couple!), and couples who each earned the maximum Social Security benefit have a combined Social Security lump sum value of over $1.1 million!

In other words, any moderate dollar amount of several thousand dollars per year, repeated for a long multi-decade period of time, seems like a really big number. Including health care expenses. Even when, for health care, in particular, it’s actually not that big of an expense relative to other retirement expenses anyway. For which we not only have retirement savings that can grow over time to support it, but also other "illiquid" but sizable “assets” like Social Security as well.

Or stated more simply, in a world where most households spend the better part of 40 years managing household cash flow to a monthly cadence of paychecks and bills… it’s arguably simply more appropriate to think about (and plan for) health care expenses in retirement as simply another (admittedly sizable but not overwhelming) line-item monthly/annual expense in retirement.

Real Factors That Influence Annual Health Care Costs in Retirement

The other reason why it’s so important to project health care expenses in retirement as annual expenses, rather than a lump sum, is that just looking at the lump sum equivalent confuses two key factors that drive (cumulative) health care costs in retirement.

The first major factor is longevity, as simply put: the longer a retiree lives, the larger the cumulative cost of health care in retirement. Spending $5,000/year for 30 years (from age 65 to 95) requires $150,000 to cover the cost (assuming the growth rate on assets matches the rate of health care inflation rate). A retiree who lives only 15 years requires only half that amount, or $75,000.

The second major factor, though, is simply the amount per year of any particular retiree’s health care expenses, which will be impacted heavily by his/her health care status and the existence of any chronic conditions. For instance, an unhealthy individual with a 15-year life expectancy who spends $10,000/year on health care expenses in retirement may have the same 15 x $10,000 = $150,000 lump sum obligation as an ultra-healthy retiree spending only $5,000/year but anticipating 30 years of retirement spending (where 30 x $5,000 = $150,000 again). But in practice, an unhealthy individual planning $10,000/year for a limited period of time has very different planning needs that may necessitate different cash flow planning trade-offs and insurance decisions than one planning for a healthy $5,000/year need for a multi-decade time horizon. Even if it’s the same $150,000 lump sum need.

In fact, the recent Vanguard/Mercer study on retiree health care expenses emphasizes how health-related factors are really the primary driver of planning for health care expenses in retirement. Because health care expenses themselves are not evenly distributed across all retirees. Instead, a subset with one or several of the most common chronic conditions – including hypertension, high cholesterol, arthritis, heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, depression, Alzheimer's and dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, asthma, and osteoporosis – actually drive the overwhelming bulk of total retiree health care costs.

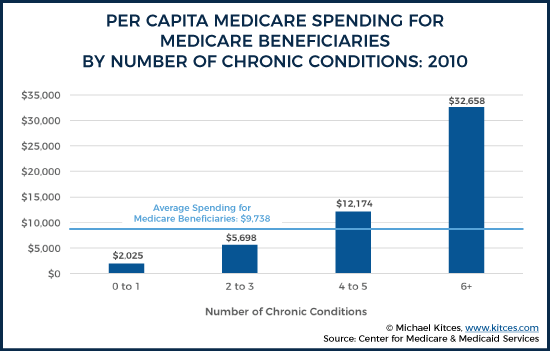

For instance, an analysis of Medicare claims from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) found that the average Medicare spending for “healthy” retirees (with only 0 or 1 chronic condition) is “just” over $2,000/year, but the amount more-than-doubles to nearly $5,700 for those with 2-3 chronic conditions, and is 6X that amount for retirees with 4-5 chronic conditions, and a whopping 16X in costs for the small subset of retirees on Medicare with 6+ chronic conditions!

In other words, understanding whether or how many chronic conditions a retiree has – which is generally known at the retirement transition, as most (though not all) such conditions have presented themselves by the time an individual is in their 50s or 60s – provides substantial additional information about the realistic trajectory of health care costs in retirement (as well as the potential likelihood or not of unusually large expenditures).

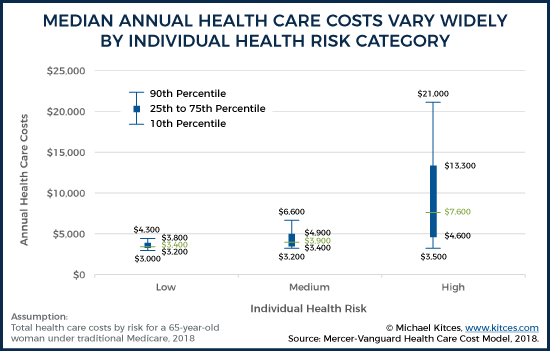

For instance, the Vanguard/Mercer model simply separates retirees into low-, medium-, or high-risk categories based on whether they have no chronic conditions, 1 chronic condition, or 2+ chronic conditions and/or are smokers. And on this basis alone, not only is there a substantial difference in the median annual health care costs – from $3,400/year for low-risk individuals to more than double that amount at $7,600/year for high-risk retirees – but there is an even more drastic range (with the upper 90th percentile at “just” $4,300/year for low-risk individuals, $6,600/year for medium-risk retirees, but a whopping $21,000/year for those with the highest health risks.

The Impact Of Medicare Premium Surcharges (IRMAA) On Annual Retiree Health Care Costs

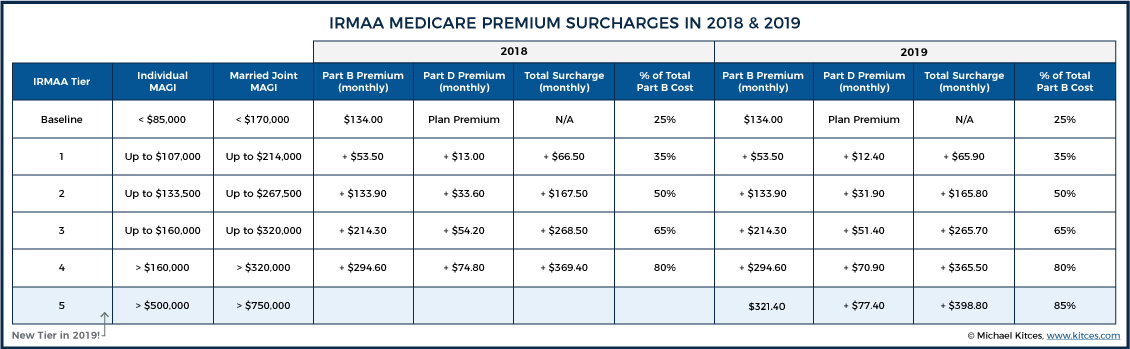

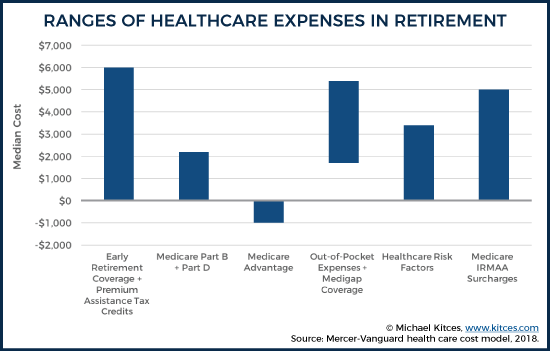

In addition to the sheer variability of out-of-pocket expenses driven by various chronic health conditions in retirement, income-based adjustments to Medicare insurance premiums for higher-income individuals can also have a substantial impact. As while Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage and Medigap supplemental policies are guaranteed issue (at least for those who enroll when first eligible), with a relatively narrow band of pricing that changes primarily just based on geography (and the available drugs in the formulary for Part D plans), Medicare Part B premiums are also impacted by income levels themselves, thanks to the so-called “Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount” (IRMAA) rules.

Specifically, the IRMAA rules stipulate that once Adjusted Gross Income (from the prior-prior year) exceeds $85,000 (for individuals, or $170,000 for married couples), there is a roughly $600/year/person increase in Medicare Part B premiums (on top of the base annual premium of $134/month or about $1,600/year), and another $150/year/person increase in Medicare Part D premiums. And that surcharge amount continues to rise as income rises, capping out at an additional surcharge of nearly $5,000/year/person in 2019 for those with more than $500,000/year of income (as individuals, or $750,000/year for married couples)!

As a result of these Medicare premium surcharges, the total annual health care cost for an individual can be substantially higher, simply because of the surcharges layered on top of the remaining premiums and potential out-of-pocket expenses. Which, when coupled to health risks and geographic variability, can produce a very wide range of potential annual health care costs in retirement, especially for those with a greater number of existing chronic health conditions!

The Health Care Cost Complications Of Retiring Early

While the data of the Vanguard/Mercer study shows that health care costs are actually rather stable and feasible to plan for on an annual basis thanks to Medicare – albeit with a little more volatility for those at the highest levels of health risk – the matter is far more complicated for those who are retiring “early,” before they become eligible for Medicare at age 65 in the first place.

Because over the past several decades, health insurance has evolved to provide a continuous flow of coverage from children covered by their parents’ plans during their early years, to obtaining their own employer coverage once they were able to work for themselves, culminating in Medicare at age 65 when they were no longer able to work anymore. Which was fine for those who worked all the way until age 65. But left a gap for those who did not work (or chose not to) and lost access to employer-based coverage, for which individually-purchased policies were not always available (due to limitations on pre-existing conditions or individual underwriting that made coverage unaffordable for those who needed it the most).

The good news is that, since the rollout of the Affordable Care Act, “early” pre-age-65 retirees do at least have one option assured to access health insurance: state health insurance exchanges. Available either during an open enrollment period, or immediately following the termination of employer coverage, health insurance exchanges mean that early retirees will at least know that they can obtain health insurance in the marketplace and without the risk of being declined or facing exclusions for (or explicitly higher premiums due to) pre-existing health conditions.

Which means, in practice, that insurance coverage during the working-age years (after "graduating" from a parent’s plan, until eligibility for Medicare) is a combination of employer coverage for those who are working, and state insurance exchanges as a backstop for those who don’t have employer coverage.

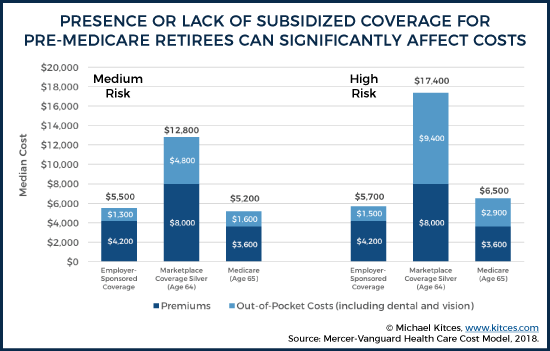

The caveat, however, is that while the state insurance marketplaces ensure that coverage will be available, it’s still necessary to pay for that health insurance from the state insurance exchanges. And while the marketplace coverage premiums cannot be priced higher based on an early retiree’s individual health conditions, the cost of coverage is based on age, which can make it quite “expensive” to purchase for near-retirees in their late 50s and early 60s, especially relative to the typical cost of (often-heavily-subsidized) employer-based coverage.

For instance, the Vanguard/Mercer study estimates that the median cost of a Silver plan on the exchange for a pre-Medicare 64-year-old is $8,000/year, as contrasted with an average cost of $5,700/year for a Silver plan for a 40-year-old, and a net cost of just $1,300/year for the typical employer plan (at least from a large corporation that provides health insurance to its employees). And a Silver plan for an early retiree is also substantially higher than the roughly $3,600/year cost of premiums for Medicare Part B, Part D prescription drug coverage, and Medigap Plan F coverage. And of course, all of these plans also have additional out-of-pocket costs beyond the health insurance premiums as well, which also tend to be higher for state-insurance-exchange-based policies than either Medicare or employer coverage… amplifying the gap even further, especially for those who are “high risk” with existing chronic health conditions.

Which means, at a minimum, that “early” pre-age-65 retirees planning for health insurance costs in retirement need to plan for the “bump” in annual premiums and potential additional out-of-pocket costs after (employer-subsidized) employer group health insurance ends, and when Medicare begins. Which in turn introduces additional planning strategies to manage those premiums by drawing on Premium Assistance Tax Credits that may be available for individuals with income up to $48,240, or married couples up to $64,960. (Another reminder of why planning for annual health care costs is a better approach than just focusing on the lump sum present value!)

Integrating Retiree Health Care Costs With The Rest Of The Plan

As noted earlier, health care costs in retirement are just one of many expenses that retirees face, and not even necessarily the biggest (trumped by more than 2-to-1 by essential food/clothing/shelter expenses alone, not to mention all the other discretionary expenses of retirement).

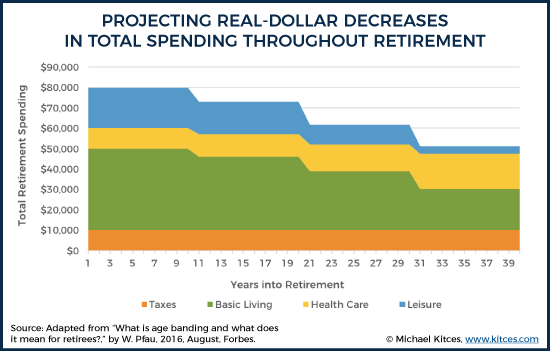

Nonetheless, given both the fact that these expenses are specific to the individual, may vary over time (especially for those who retire before age 65 and then later transition to Medicare), and that medical expenses inflate at their own higher-than-the-general-rate-of inflation (at 3.6% vs 2.2%, respectively, over the past 20 years), arguably health care costs should really be projected separately from the remainder of retiree expenses in analyzing a retirement plan. Not to mention that out-of-pocket expenses for health care also tend to rise over time, simply because retirees tend to have more health events as they get older (in addition to the fact that the cost of those health care expenses is rising at a higher rate of inflation).

Notably, though, retirement researchers have found that other more discretionary spending in retirement tends to decline in later years, even as health care expenses disproportionately rise (due to both higher utilization and a higher inflation rate). In fact, the Vanguard/Mercer study notes that the average spending on health care rises almost 36% from age 55-64-year-old retirees to those who are age 75+, while other spending falls by 29% over the same time period (and tends to fall even further in a retiree’s 80s!). Except given that health care expenses are ultimately still only a moderate slice of a retiree’s total budget, in the end, health care expenses rise “just” $1,116/year (from $3,046 to $4,162) while overall spending falls by $10,498 (from $35,825 to $25,327). Which means even if/when/as health care expenses rise in the later years’ of retirement, it’s more than offset by other retirement spending decreases anyway!

In other words, a key aspect of the Vanguard/Mercer study is that in the end, retirees may be far more distressed about health care expenses than the actual risks they face, both because medical expenses in retirement are actually far more stable than most realize thanks to the availability of Medicare plus Medigap insurance (except, perhaps, for a small subset of the highest risk retirees with multiple chronic conditions who at least face some upside out-of-pocket cost risk), and because, in practice, discretionary spending tends to naturally decline by far more than health care expenses rise anyway in the later years of retirement.

Of course, this still doesn’t address the potential risks of needing long-term care in particular, but as Vanguard emphasizes, LTC needs are actually separate and distinct from health care expenses in retirement. Both because long-term care expenses can ultimately be much larger – with an estimated 15% of retirees facing a greater-than-$250,000 expense in retirement – but are also far more likely to be non-existent (with 48% of retirees experiencing no LTC expenses at all, and another 25% needing less than $100,000 in total). Which actually suggests that long-term care insurance should be especially appealing to further stabilize this risk, converting it from an unlikely-but-potentially-very-sizable unknown expense into a stable-and-known (albeit, not inexpensive) insurance premium. Especially if the long-term care insurance industry can better develop alternative high-deductible LTCI options.

Real Planning For Health Care Expenses In Retirement

The good news of planning for annual health care expenses in retirement is that, when the costs are known and relatively stable, it is feasible to actually plan for the costs, through some combination of simple saving for retirement in the first place to have assets to cover the costs, leveraging savings for retiree health care expenses in particular with an HSA, planning to maximize Premium Assistance Tax Credits (to the extent feasible) during the years of state marketplace coverage before Medicare begins, and making good proactive planning decisions about Medicare enrollment itself (particularly with respect to selecting the best Part D prescription drug plan based on current medication needs, and choosing the right Medigap supplemental policy to further balance between higher premiums and lower out-of-pocket cost exposure).

Still, though, as Vanguard notes in its study, the process of planning for annual health care costs in retirement requires some real planning. Both in consideration to selecting the right type of coverage, in considering the health of the retiree and any known chronic conditions that can most materially impact health care costs in retirement over time, and in simply planning for the changes to household cash flow that will occur in the transition from (often-less-expense) employer-based coverage to either more-expensive Medicare or sometimes-much-more-expensive marketing coverage prior to age 65.

In other words, planning for annual health care expenses in retirement is effectively a form of layer cake, where the various factors – from coverage types, to early retirement, out-of-pocket expenses (or managing them with a Medigap policy), personal health risk factors, and high-income Medicare premium surcharges, all stack together to produce a projected annual cost for health care in each year in retirement. Recognizing that some years may still be higher with unexpected out-of-pocket medical expenses… but that for those at high risk for such costs, once a Medigap supplemental plan is in place, even those costs at the 90th percentile add “just” another $5,700/year (relative to someone with only medium risk).

Nonetheless, the fundamental point is simply that health care costs in retirement aren’t a lump sum, they’re an ongoing annual one – and one that retirees may have actually become overly fearful of, despite the relative stability and “plannable” nature of what are actually predominantly known Medicare and Medigap premiums and typically relatively modest out-of-pocket expenses (except for a subset of high-risk individuals with multiple chronic conditions, who in turn can plan accordingly). And even the looming rise of those health care expenses in later years tends to be more-than-offset by other spending decreases anyway. Not that that means retirees and their advisors shouldn’t still plan for health care expenses. But ultimately, using resources like the Vanguard/Mercer study, health care expenses can and should simply be planned for as an annual ongoing projected cost… just like virtually any/every other expense in retirement!

Leave a Reply