Executive Summary

In order to do a financial plan for a client, it's necessary to determine the client's time horizon - which at the most fundamental level, is the time the client is expected to live. The client's life expectancy can impact the number of years of anticipated retirement, and even the age at which the client chooses to retire. Unfortunately, though, it's difficult to really estimate how long a client will live, and the consequences of being wrong and living to long can be severe - total depletion of assets. As a result, many planners simply select a conservative and arbitrarily long time horizon, such as until age 95 or 100, "just in case" the client lives a long time. Yet in reality, the life expectancy statistics are clear that the overwhelming majority of clients won't live anywhere near that long - unnecessarily constraining their spending and leading to a high probability of an unintended large financial legacy for the next generation. As a result, some planners are beginning to use life expectancy calculators to estimate a more realistic and individualized life expectancy for a client's particular time horizon. Will this become a new best practice?

The inspiration for today's blog post was a recent conversation I had with another planner about determining an appropriate time horizon for a client's retirement plan. Like many planners, her approach was to set an arbitrary but conservative time horizon for clients - e.g., until age 95 - and then modify it further if the client has longevity in the family. In a particular recent situation, she had a client whose mother had lived to age 97, so she had decided to project the couple's retirement plan out to age 100.

Setting A Retirement Time Horizon

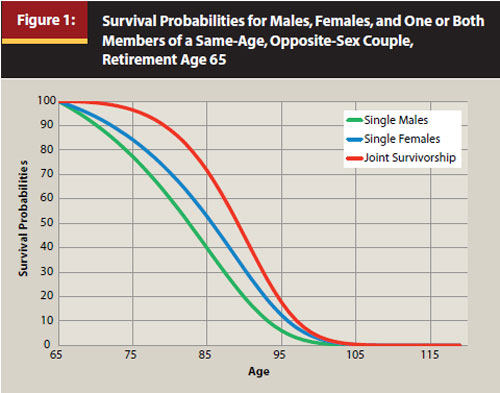

While it's certainly prudent to be conservative in setting a time horizon for retirement withdrawals, and to take into account an individual's personal and family circumstances (e.g., "good genetics" and longevity in the family), I couldn't help but wonder if this is still too conservative of a projection. After all, as the chart below indicates (from Spending Flexibility and Safe Withdrawal Rates by Michael Finke, Wade Pfau, and Duncan Williams from the March 2012 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning, and based on the Social Security Administration period life table for 2007), the probability of a joint life expectancy of 30 years for a 65-year-old couple (to age 95) is already as low as 18%. A 35-year life expectancy for that same couple (to age 100) has a mere 3.7% likelihood. Which means adding 5 years of longevity for "good genetics" on top of an already low probability scenario is a pretty huge adjustment.

Yet the problem isn't just adding 5 years of joint life expectancy in light of the client's family longevity. The real concern is adding 5 years of joint life expectancy for what in the end was just one family member. After all, even a relatively unhealthy family with poor longevity can still end out with one long-living family member due to random chance! In other words, taking the life expectancy of one family member from the past and generalizing it to the client's future isn't necessarily much better than taking an example of one technology stock like Apple and concluding that all technology stocks will be fantastically profitable in the future. Especially if you're planning for a couple, and the family member is only from one side of the family!

Individualized Life Expectancy

So what's the alternative? Some planners are beginning to use life expectancy calculators available on the web, that analyze a wide range of factors from family longevity to health issues to behavioral habits, to try to get a more accurate picture of the client's life expectancy than a few anecdotal family data points. The most popular option appears to be the site LivingTo100, which draws on data from the New England Centenarian Study to try to get a good picture of how likely it is for the client to live to age 100 and what his/her individualized life expectancy would be.

Following this approach, the client (or each member of the couple) goes through the calculator's questionnaire and gets a personalized life expectancy. The plan can then be crafted according to the customized life expectancy factors, rather than generic assumptions. While this is straightforward for a single client, it's a little messier for a married couple, as the software still only gives an individual life expectancy for each member of a couple, and not a joint life expectancy for both. A rough rule of thumb would add about 5 years to the longest life expectancy of the couple to adjust for joint life expectancy.

At the client's discretion, the planner may then add further to the life expectancy to be more conservative, as a life expectancy by definition is a 50th percentile result, which means there's a 50% chance the client could outlive the time horizon. On the other hand, it's worth noting that if the Monte Carlo results are already very conservative, it's important not to also make the life expectancy factor extremely conservative, or the combined probabilities of failure may be so low that the client's lifestyle is unnecessarily constrained when small adjustments along the way would have been sufficient to keep the client on track. After all, a 90% Monte Carlo success rate for a 90th percentile life expectancy is actually a 99% probability of success for the overall plan.

Is It Worth Estimating Life Expectancy At All?

Many planners I know still suggest it's not necessary or appropriate to estimate a client's life expectancy at all, given that life expectancy is just a probabilistic estimate, and there's always still a 'risk' that the client will live to age 100. Accordingly, they suggest, we should just set every client's retirement time horizon to an arbitrary conservative number like age 95 or 100, just to be certain the client doesn't run out of money on the planner's watch.

Yet the reality of the life expectancy tables is that the overwhelming majority of clients will never live this long, or even come close. And even while life expectancy continues to increase over time, most improvements in life expectancy have been driven by eliminating diseases and reducing mortality for the young (especially infant mortality); the death rate for people in their 80s and 90s has only fallen very slightly in the past 50 years.

This is problematic because, in the end, excessive conservatism does have a cost - it can greatly impinge on the client's ongoing lifestyle and opportunity to enjoy the money while health is good enough to really enjoy it. As noted in the blog earlier this week, the difference between a 40-year time horizon and a 20-year time horizon is a 5%+ safe withdrawal rate versus a less-than-4% withdrawal rate. Which means a couple that has some health issues and a low likelihood of living much beyond 20 years, that still receives a 35-40+ year arbitrary time horizon, must endure a lifetime spending cut of 20% per year forever (and a very high likelihood of 'accidentally' leaving a giant unspent financial legacy behind)! Alternatively, a client with a shortened life expectancy might even choose to retire earlier, knowing that the retirement time horizon isn't as long, and that consequently not as much savings is needed.

Ultimately, it seems to me that because being too conservative does have a cost - along with being too aggressive - that life expectancy calculators may well become a best practice for planners in the future, as it represents an effective means to ensure that the client's plan matches a time horizon that is reasonable given his/her life expectancy, that is neither too long nor too short. Of course, clients may adjust up or down from there, but at least they will be grounded to a reasonable life expectancy starting point.

So what do you think? Have you ever used a life expectancy calculator to estimate a time horizon for the client's retirement plan? Would you encourage a client to spend more if he/she had a materially below-average life expectancy? Is a life expectancy calculator a more objective way to estimate life expectancy and time horizon for a client? Is there a particular tool that you use? Or do you just consider it a waste of time, or a risky alternative to just picking a conservative time horizon?

Michael,

Thanks for addressing this. Longevity is an important determinant for the appropriate retirement income strategy. What you are describing here is about choosing the appropriate planning age.

Another alternative for doing Monte Carlo simulations to analyze strategies is to take the spending path created by the strategy in each simulation, and then multiply each of the spending values by the probabilities of surviving to each age, which you can get from the figure you showed. This puts a lot more importance on spending early in retirement and very little weight is given to how much you spend 30 or 40 years in to retirement. It will basically lead to favoring strategies with higher spending early in retirement and less spending later in retirement.

For reasons unrelated to whether retirees may naturally wish to reduce spending as they grow older, I struggle with whether or not this makes sense. It does sort of make sense to plan for spending less when you are 95, since there is a much lower probability of surviving to that age.

What do you think?

The only times I would find it appropriate to use a shorter life expectancy is when you know, with relative certainty, that an individual will not live beyond a certain age (i.e. they have a terminal illness).

In situations where this is not the case, I still think it is prudent to run a projection out to 95 or 100. Especially when someone is only 50 or 60 years old, there is no way to know when their plan will end.

I always explain that we’re being conservative in our estimates, and that we can adjust as necessary as time goes on and we gather more information about any potential health conflicts the client may face.

In response to Michael’s post above, while I agree with the theory from a mathematical standpoint (similar to how some analyst determine a stocks target price), I think there are two problems.

One, that process could very easily leave clients who are fortunate enough to live longer with much less money than they need in their later years.

And two, it has the potential to skew an investors perception of potential advisors.

Imagine a situation in which a client is meeting with two advisors, one who uses the monte carlo analysis and one who just uses age 95. The monte carlo is inherently going to assume a younger end plan date than 95, and will therefore assume the client can spend more per month/year.

Similar to how real estate agents “buy a listing,” I can see a situation in which an advisor can say, “well, I am able to generate $2,000 more in income per month.” While we know the reasons for this, an unknowing client can fall prey to that analysis.

I like the idea of using the longevity calculator as an additional data point to use to determine life expectancy for clients. However, I still think I would stay on the conservative side. The risk in doing the other seems to great.

Goodness gracious. Why would you ever consider a long term plan for a client that has them fully depleting assets at any age? The goal should be to have the client’s assets outlive them under every circumstance. Never cut it so close that you’d ever consider using a life expectancy calculator. Healthier lifestyles and medical technology is such that you can not use previous generations as a benchmark for determining longevity. There should never be an end date with a plan. Too many unknown variables.

Jason,

Shouldn’t it be up to the client to determine whether they want to cut their lifetime spending by 25% to protect against something that has a 1-in-100 chance of occurring?

Yes, every now and then we have clients who have a stated goal of leaving a significant legacy to their children. However, in my experience most clients DO not say “my primary goal is to leave millions behind, just in case I happen to have better longevity than 80%, 90%, 95%, or 99% of my peers”.

Excessive conservatism has a very real cost, when people die with massive wealth left over and never have the opportunity to enjoy it because they were counseled to defend against radically improbable scenarios.

Respectfully,

– Michael

I like to refer people to the “living to 100” calculator and have them go through it to help inform their decisions on how long to plan. General population studies underestimate lifespans for most financial planning clients due to differences in education, health, and lifestyle. However, I’m not sure that a single time horizon is the answer, since at age 65 your probability of dying at any single age is less than 5%. For many couples, an early death of one spouse (and the loss of income, such as from Social Security or pension) is as devastating as a long lifespan.

Cheryl,

As memory serves, the LivingTo100 calculator asks questions about numerous education, health, and lifestyle factors. So these are already being controlled for. In fact, to me that’s the whole point of a tool like LivingTo100, versus just pulling out a standardized mortality table; the customized tools control for the factors you’re noting here.

Respectfully,

– Michael

I still think including longevity at the attained age as one of the variables in the Monte Carlo simulation would be the best approach. There are not many of us that plan around market events with a 1 or 2% probability, but by choosing an arbitrary date well beyond NLE was are planning for a mortality event with just as low a probability.

As an educator who does some financial advising and a relatively new member of FPA, I was surprised that using longevity calculators is NOT standard practice for planners. For years my Family Finance college students have had an assignment to complete 3 longevity calculators to determine their expected lifespan (in Mormon Utah, the state with the longest lives). This info is used in estimating their retirement needs. I recall one student looking very grim as she volunteered to share the results of her experience with the class. I expected she had inherited bad genes and would only live to 70, but no, she was depressed that her projected lifespan was 104! I suggested she better start smoking, drinking, and partying. The first ‘assignment’ my financial advising clients have is to use the longevity calculators to project their lifespan. Finke, Pfau & Williams recommended regular recalculating of retirement needs; would it not be logical to also ask clients to periodically revisit the longevity calculators?

There is very little discussion of percentile life expectancies on the web, so I have written a percentile life expectancy calculator at aacalc.com One thing on the topic I’d like to mention is that in the above article where it says “a 90% Monte Carlo success rate for a 90th percentile life expectancy is actually a 99% probability of success”. This is true, but only if the Monte Carlo simulations fail late, and the outcome is determined by the 90th percentile. At the other extreme, if the Monte Carlo simulations fail early, and failure is also guaranteed to occur beyond the 90th percentile, then I think the overall success rate could be as low as 81%. This broad range (81-99%) points to the importance of techniques that incorporate stochastic life expectancy directly into the Monte Carlo simulator.