Executive Summary

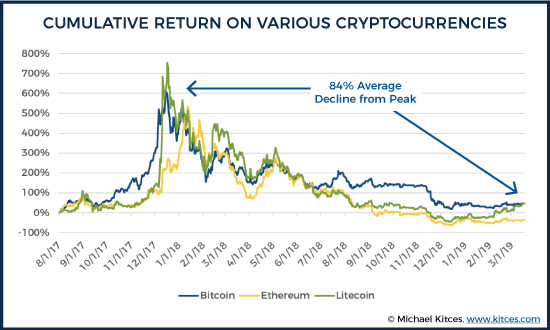

On October 31, 2008, the person (or persons) going by the name of Satoshi Nakamoto first posted the paper titled, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” Within months, the first Bitcoin had been “mined” setting off a technological and cultural revolution. And over the next decade, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies would see a dramatic rise in distribution and price, culminating in an epic 2017 that saw the value of many cryptocurrencies grow by more than 1,000%!

Unfortunately, just as public infatuation with cryptocurrencies seemed to reach a peak, so did its price, leading to a disastrous 2018. During the year, many cryptocurrencies lost upwards of 80% of their value, leaving investors with sizeable losses, and questions about what to do, if anything, to make the most of their losses (at least from a tax perspective).

Fortunately, to that end, back in 2014 the IRS released IRS Notice 2014-21, providing its first substantive guidance on the taxation of Bitcoin and cryptocurrency transactions. Notably, the IRS determined that cryptocurrencies are “property” for Federal tax purposes, and not currency. Thus, the sale of cryptocurrency results in capital gains and losses, rather than ordinary income.

In general, the basis of a taxpayer’s cryptocurrency is the price paid to acquire the currency (in U.S. dollars) from its previous owner, typically via an exchange. In other words, the basis of an investment is what you paid to acquire it. In the context of cryptocurrency that is mined, though, there is no “purchase” transaction in the first place. Instead, the act of mining itself is treated as an income-producing activity, such that the fair market value of the cryptocurrency is included in gross income when it is mined. In turn, that fair market value becomes the miner’s cost basis in the cryptocurrency property going forward.

For taxpayers who liquidated cryptocurrency positions at a loss in 2018, the “planning” options are unfortunately somewhat limited. At this point, the best that can be done is to use any 2018 cryptocurrency losses to offset other 2018 capital gains and up to $3,000 of ordinary income. Any additional (cryptocurrency and other capital) losses must be carried forward for use in future years.

Taxpayers who currently hold cryptocurrency positions with unrealized losses can still choose to liquidate those positions in 2019 and use those losses to offset other portfolio gains (e.g., enabling investors to minimize the impacts of rebalancing out of other investment positions that have accrued substantial capital gains).

Unfortunately, though, harvesting cryptocurrency capital losses may be easier said than done, particularly for long-term cryptocurrency investors whose early purchases have accumulated in value, as FIFO tax treatment for multiple lots of cryptocurrency is likely required. On the other hand, because cryptocurrency is “property” but not (at least at this point) treated as an investment security, it appears the Wash Sale Rule does not apply to sales of cryptocurrency. Thus, positions with losses can be sold in order to be able to use the loss for planning today (or to “bank” the loss for future use), and still repurchased shortly thereafter (for those who want to continue to HODL), enabling the investor to continue to participate in future appreciation (at least if they’re still optimistic about cryptocurrency investment potential in the first place).

Finally, it’s worth noting that the digital nature of cryptocurrency makes it more susceptible to theft-by-hack (or other means), while its ethereal nature makes it more likely to be truly lost (via lost keys or cold-storage hardware) than other assets. Which is important because unfortunately, such losses would be treated as casualty losses which, after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, are generally no longer deductible at all!

Many crypto-advocates believe its long-term growth potential and viability as an asset class remains strong. Nevertheless, many investors first entered into the crypto-game in 2017 – when interest in the asset class grew exponentially due to its dramatic rise in price – and are now left trying to make the most of their losses.

The origins of cryptocurrency are generally traced back to October 31, 2008, when the person (or persons) going by the name of Satoshi Nakamoto first posted a link to a paper entitled, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” As the name implies, the paper described a peer-to-peer version of “electronic cash”… one that would allow payments to be made between parties directly, and without the need of a financial institution or other trusted intermediary to facilitate the exchange.

Just months later, in January of 2009, Nakamoto “mined” the “genesis block” – the first block of the bitcoin blockchain – and per the Bitcoin protocol, he received 50 bitcoin (BTC) for that effort. One could argue that, at the time, Nakamoto’s bitcoin reward for mining the block was both priceless (in that the coins were the first-ever mined on what would become a revolutionary platform), and, essentially, worthless (given that, at the time, there was no real market for Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies).

Roughly two years later, however, in March 2010, the first trading price of Bitcoin – $0.003 per coin – was recorded by the bitcoinmarket.com exchange (which has since closed). And just months after that, in May 2010, what is believed to be the first real-world commercial use of Bitcoin occurred when programmer Laszlo Hanyecz infamously purchased two Papa John’s pizzas for 10,000 Bitcoin.

Over the next seven years, the awareness of Bitcoin and cryptocurrency continued to rise, as did its price. But none of that was anything like 2017.

The Wild Ride of Bitcoin (And Other Cryptocurrencies) In 2017 - 2018

It wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration to say that 2017 was marked by Bitcoin mania. At the start of the year, the price of a Bitcoin was roughly $1,000. During the year, however, the price of Bitcoin grew exponentially, and by December of 2017, the price of just a single Bitcoin reached nearly $20,000.

The dramatic increase in price, coupled with tales of “instant riches” caught the attention of the media, and by late 2017, it was hard to open a magazine or watch television without coming across some sort of Bitcoin-related story. So-called experts made wild predictions about Bitcoin's continued growth, with some even speculating that the price of Bitcoin would reach $1 million per coin by 2020 (which seems all but impossible now). Unsurprisingly, the media, the hype, and the prospects of missing out on the next “gold rush” led many people to jump into the Bitcoin market for the first time, even as prices continued to make new all-time highs seemingly by the day.

Unfortunately for many, the Bitcoin “bubble” popped in 2018. By the end of 2018, Bitcoin was off nearly 80% from it’s high of nearly $20,000, closing out the year at under $4,000. Worse yet for investors who diversified into other cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin’s performance was actually one of the cryptocurrency market leaders, with prices of many other cryptocurrency coins falling more than 90% or more.

Thus, thanks to the 2017 hype that saw a massive number of new entrants into the cryptocurrency market (and, in particular, more “everyday folks”), and even though 2018 was not the first time that there was a significant pullback in the price of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin notably lost roughly half of its value in 2014 after the largest exchange at the time, Mt. Gox, was hacked, and roughly 850,000 bitcoin were stolen), this is the first time when substantial amounts of “regular” investors are looking around and trying to figure out what, if anything, they can do with their 2018 Bitcoin and cryptocurrency losses.

For Tax Purposes, Cryptocurrency Is Property, Not Currency

As interest in the nascent field of cryptocurrency began to grow and its user base began to expand in the early 20-teens, questions regarding the tax treatment of transactions involving Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies began to surface with greater regularity. Ironically, the biggest question was simply whether cryptocurrency, as its namesake would suggest, is even a currency (at least for tax purposes) to begin with, or if is some other type of asset instead.

In response to this question and others, on March 23, 2014, the IRS released IRS Notice 2014-21, in which it described how existing tax law applies to transactions involving “virtual currency” via a series of questions and answers. Notably, Q&A-1 emphatically answered the question, “Is cryptocurrency a currency for tax purposes?” with a resounding “no,” stating:

Q-1: How is virtual currency treated for federal tax purposes?

A-1: For federal tax purposes, virtual currency is treated as property. General tax principles applicable to property transactions apply to transactions using virtual currency.

The significance of the IRS’s position cannot be overstated. By designating cryptocurrency as “property” rather than currency, sales of cryptocurrency generally produce capital gains or capital losses, and not ordinary income or losses.

Thus, investors engaging in cryptocurrency transactions that produce gains are able to benefit from the favorable capital gains rates (assuming that they have held the investment for more than one year), while those with losses are limited in their ability to use such (capital) losses under the normal rules that apply for netting capital gains and losses.

Determining Basis In Cryptocurrency To Calculate Capital Gains

In order to determine whether an investor has a gain or loss with respect to a cryptocurrency transaction, it is first necessary to determine the investor’s basis. For many, this should be of minimal complication. With the rise of popular cryptocurrency exchanges, such as Coinbase, Gemini, Coinmama, CEX.IO, and Bitstamp, many cryptocurrency owners have acquired their coins through more “traditional” means, where it’s straightforward to determine how much they put into the purchase in the first place.

Said differently, they used an exchange as an intermediary (which is, ironically, one of the things the creator(s) of cryptocurrency were trying to avoid) to find a willing seller, similar to the way investment securities are traded on stock exchanges. Accordingly, for such investors, the basis of the virtual currency acquired via an exchange is simply their purchase price (in U.S. dollars at the time or purchase), plus any related transaction expenses such as commissions (which is essentially identical to the treatment securities investors receive when they purchase securities via an exchange).

Unlike investment securities like stocks and bonds, however, which can only be acquired from someone else (unless you are the originator of such a security), Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies can be both acquired from someone else and created. The production of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies is known as “mining,” which is a complex process where computers verify data (performing the verification function that historically has been handled by a trusted intermediary, such as a bank or government), and add new blocks to the public blockchain to report and record new data (such as the transfer of Bitcoin between two persons), and in exchange for conducting such activity Bitcoin miners receive a small allocation of Bitcoin directly in exchange for their (computer’s) work.

And just as Satoshi Nakamoto received 50 Bitcoin for the creation of the first block on the Bitcoin blockchain, crypto-miners today continue to receive rewards for adding new blocks to the chain. (Though today, the reward for adding a new block to the chain has decreased to “just” 12.5 Bitcoin). For tax purposes, when a miner successfully mines a virtual currency – the reward for doing the work to verification work needed to maintain the integrity of the blockchain – the fair market value of that virtual currency is included in the miner’s gross income (akin to wages or other compensation received for work delivered). The same is also true for individuals who are compensated with cryptocurrency for services rendered. The fair market value (the amount included in gross income) of the cryptocurrency received as compensation then becomes the taxpayer’s basis for determining future capital gain or loss on that cryptocurrency to the extent they continue to hold it after mining/receiving it.

Example #1: Several years ago, as a hobby, Jason built a powerful computer to mine Bitcoin. On December 7, 2017, his “rig” successfully verified a block of transactions and performed the necessary cryptography to add a new block to the Bitcoin blockchain. By doing so, Jason “mined” 12.5 Bitcoin.

At the time of Jason’s mining, Bitcoin was worth $15,000 per coin. Thus, when filing his 2017 tax return, Jason should have reported 12.5 x $15,000 = $187,500 of ordinary income attributable to his mining efforts. That $187,500 would then become his cost basis in the coins for any future sale.

Example #2: Julie is a graphic designer who works virtually with most of her clients. In October of 2017, Julie was contacted by Bagel Bytes, an internet bagel café, to do some work for its new website. Generally, Julie would charge $10,000 for this work, but she agrees to accept 1 Bitcoin instead.

Over the next few months, Julie completes her work, and per their agreement, on December 7, 2017, the owner of Bagel Bytes transfers Julie 1 Bitcoin for her efforts. At the time, the price of a single coin was $15,000. Although Julie only performed $10,000 worth of work, because she is being paid in property, the fair market value of that property (on the date of receipt) must be included in her income. Thus, since she actually received $15,000 of Bitcoin at the time of completion, she will report $15,000 in income, and that $15,000 fair market value when received becomes her cost basis for any future sales.

Planning With 2018 Realized Cryptocurrency Losses

While the mantra of many cryptocurrency enthusiasts is HODL – which, depending upon whom you ask, is either “hold,” but misspelled, or an acronym for “Hold On for Dear Life” – many cryptocurrency investors “cried Uncle” at some point during the 2018 coin-pocalypse, throwing in the towel and leaving themselves with capital losses related to their cryptocurrency transactions.

Unfortunately for such investors, though, since 2018 is already over, there isn’t much planning that can be done when it comes to making the most of those losses.

At this point, it’s simply a matter of aggregating those cryptocurrency losses with other capital gains and losses from 2018 (e.g., from any other stock, bond, mutual fund, ETF, or other investment property transactions). If, when combined, total capital gains for the year is a net negative number, up to $3,000 of those losses can be used as an ordinary loss, offsetting “regular” income, like W-2 wages, interest, and distributions from retirement accounts. Any additional losses must be carried forward for use in future years.

Planning With Unrealized Cryptocurrency Losses

For investors with unrealized cryptocurrency losses still in their portfolio – in other words, those who have been “hodl-ing” Bitcoin on the way down and still haven’t actually sold – the first course of action from a tax planning perspective should be to look at other positions within their portfolio (both cryptocurrency and more traditional investments) and determine if it would make sense to liquidate some positions with gains and to use the cryptocurrency losses to offset that gain.

This may be especially appealing for longer-term investors, given that the current bull-market run officially just recently turned 10 years old. Which means there are many investors with positions in their portfolios that have substantial gains. At times, such investors may wish to sell such investments for diversification purposes – or simply because they believe there may be better opportunities available for the use of that capital – but they are hesitant to do so because of the potential tax consequences and need a workaround strategy. If there are available cryptocurrency losses, those losses may alleviate the tax concerns and allow for the desired sale.

Of course, there are certainly some cryptocurrency investors who were “in on the action” earlier than most, and may still have substantial gains in some or all of their cryptocurrency positions purchased in 2016 or prior (notwithstanding the magnitude of 2018 losses). If so, losses in other more-recently-purchased cryptocurrencies could actually be used to offset the earlier gains.

No 1031 Exchanges For Cryptocurrencies With Gains After TCJA

Notably, the strategy of using recent cryptocurrency losses to diversify out of earlier cryptocurrency purchases that still have big gains is of even greater importance since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Because amongst many other changes, TCJA changed the language of IRC Section 1031 to allow for like-kind exchanges only of “real property” instead of just “property.”

Thus, Congress slammed the door on any possibility that a 1031 exchange could be used to diversify out of gain-heavy cryptocurrencies. Instead, to both diversify those gain-heavy positions and to avoid taxes, the gain on the disposition of those cryptocurrency positions must be offset by other losses, including those from other cryptocurrency positions. (Or to the extent the gains cannot be offset with losses, then capital gains taxes will be due.)

FIFO Treatment Is (Likely) Required For Separate Cryptocurrency Lots

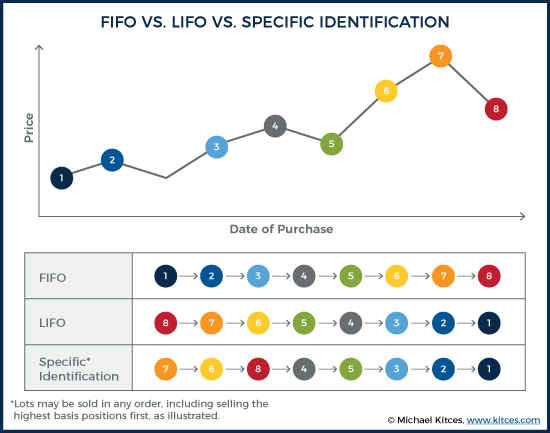

One of the unfortunate challenges for long-term cryptocurrency investors – who may have a mixture of gains and losses for coins acquired over the years – is ambiguity over how, exactly, to determine which coins are being sold (with which cost basis).

As while IRS Notice 2014-21 answered many of the questions that investors and tax professionals related to cryptocurrency transactions, it failed to address all of them. And specifically, one question that has yet to receive a definitive answer is whether investors have the ability to choose their method of accounting (e.g., the first-in, first-out (FIFO) method, the last-in, first-out (LIFO) method, or the specific identification method) when selling cryptocurrency.

By default, IRS Treasury Regulation 1.1012-1(c)(1) requires the use of the FIFO method, which means that the first Bitcoin purchases made by an investor would also have to be the first Bitcoin sold by that investor. For an early adopter, that could mean selling a low-cost-basis, highly appreciated Bitcoin purchased in 2013 before a high-purchase-price, highly depreciated “loser” Bitcoin purchase in late 2017.

Notably, the IRS does allow for the default FIFO method to be overridden, and either the LIFO or specific identification methods to be used when an investor can make an “adequate identification” of the asset in question. But therein lies the rub. How can you possibly make an adequate identification with respect to cryptocurrency? One Bitcoin, for instance, is indistinguishable from the next.

Thus, without being able to make an “adequate identification” (and more specifically, an “adequate identification” in the eye of the IRS), the FIFO method must be used.

In terms of application to cryptocurrency more broadly, though, the FIFO treatment would be applied on a per coin basis, as different types of cryptocurrency coins are identifiable from one another based upon their code. Thus, for instance, if an investor holds Bitcoin, Litecoin, and Ethereum positions and decides to sell a portion of their Litecoin, only the prior Litecoin purchases would be analyzed to determine which lot (i.e., the basis) of the Litecoin is being sold (using the FIFO method).

For those with multiple “wallets” (a software program in which cryptocurrency is stored), who wish to take a moderately more aggressive tax position, the FIFO method of accounting could potentially be applied on a per-wallet basis. But for those who wish to really push the boundaries and try to use either the LIFO or specific identification methods, just know that you’re skating on the proverbial “thin ice.”

The Wash Sale Rule Likely Does NOT Apply To Cryptocurrency Transactions

IRC Section 1091 details a provision of the law known as the “Wash Sale Rule.” The Wash Sale Rule is, in short, a rule that was put in place to prevent investors with a loss from selling their loser-investment, and then just repurchasing it back again in short order (so they’re never actually out of the market).

More precisely, the rule prevents an investor from claiming a loss for any stock or other security sold if that stock or security (or one that is substantially identical) is (re)purchased anytime during the period of time beginning 30 days before the date of the sale (of the stock or security for which there would be a loss) and ending 30 days after the date of the sale. If such a transaction does take place, the loss on the sale is disallowed, though investor is allowed to increase the basis in the new investment by the otherwise-disallowed loss (which means the loss isn’t itself permanently lost, but simply deferred to the future).

Notably, however, the Wash Sale Rule applies do not apply to property in general, but rather, only to the sale of “stocks and securities.” There is no doubt that cryptocurrencies are not shares of stock, and to date, the IRS’s position has been that cryptocurrencies are not investment securities.

Thus, it appears that the wash sale rules do not apply to cryptocurrency transactions, as IRC Section 1091 reads, in part:

“In the case of any loss claimed to have been sustained from any sale or other disposition of shares of stock or securities where it appears that, within a period beginning 30 days before the date of such sale or disposition and ending 30 days after such date, the taxpayer has acquired (by purchase or by an exchange on which the entire amount of gain or loss was recognized by law), or has entered into a contract or option so to acquire, substantially identical stock or securities, then no deduction shall be allowed under section 165 unless the taxpayer is a dealer in stock or securities and the loss is sustained in a transaction made in the ordinary course of such business.”

Taking the view that the Wash Sale Rule does not apply to transactions involving cryptocurrency, one could argue that virtually any time you have a loss in a cryptocurrency position, it makes sense to sell the position and then simply buy it back again (for those who otherwise want to continue to HODL). As long as transaction costs aren’t prohibitive, harvesting that loss can then either be used to offset other current gains (in cryptocurrency or any other investments) or simply “banked” for future use. Furthermore, since it appears that you can repurchase the cryptocurrency shortly after you sell it, this strategy (sell and buy back shortly thereafter) would seem to make sense even if you believe the cryptocurrency position will rebound in the future.

That said, investors should be careful not to push the boundaries of this strategy too far. For instance, if a sell and a buy order are made virtually simultaneously, the IRS could simply try to attack the economic substance of the transaction. For instance, if the investor sold Bitcoin and literally bought it back 10 seconds later, the IRS might maintain that the investor never substantively changed their economic position with a sale at all.

Whether the IRS would win that argument is anyone’s guess, but it’s probably not a battle worth fighting. Instead, cryptocurrency investors should just wait a "reasonable" amount of time between the sale and the repurchase. And given that cryptocurrency exchanges are open pretty much 24/7 and the price of coins often fluctuates by several percentage points during the day, even putting just a few hours between a sale and a purchase can go a long way to refuting any lack-of-economic-substance argument, while still harvesting losses and preserving the bulk of the cryptocurrency investment to become/remain (re-)invested for the future.

Tax Losses Lost For Lost Cryptocurrency After TCJA

Transactions involving cryptocurrencies that result in losses are one thing, but losing the actual cryptocurrency itself is entirely different. Say, for instance, that a “cold storage” device (an offline cryptocurrency wallet) is taken, or that the “key” to access one’s cryptocurrency is lost, or that your online exchange is hacked and your coins are stolen… what then?

Unfortunately, in light of changes made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, it would seem as though such losses would be nondeductible in anyway. As “property” the theft, destruction or loss of cryptocurrency would be considered a casualty loss. Yet such losses (other than those attributable to a federally declared disaster area) were eliminated by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act through the year 2025. Thus, the true “loss” of cryptocurrency results in no loss for tax purposes under the current law. It must actually be sold in a transaction to recognize (and claim a tax loss for) the loss.

2017 saw the dramatic rise of cryptocurrency in both pop culture and price. Unfortunately, the following year proved to be disastrous from the point of view of investors (especially those who piled in in 2017), with most cryptocurrencies falling by upwards of 80% in 2018.

In light of this dramatic decline, many investors have either sold cryptocurrency positions with losses, or hold positions with current losses. Unfortunately, the IRS’s classification of cryptocurrency as a “property” somewhat limits investors’ abilities when it comes to making use of those losses. That is compounded by the likelihood that FIFO treatment must be applied to cryptocurrency transactions. Nevertheless, some savvy planning and a bit of knowledge can help such investors make the most of their cryptocurrency losses from 2018, and avoid problems with the IRS as well.