Executive Summary

Financial knowledge plays an important role in enabling individuals to engage in good financial behavior. However, like other forms of knowledge, financial knowledge is subject to decay if we don’t apply and reinforce that knowledge regularly. While this may seem fairly obvious, the reality is that the many decisions we make – including the decision to retain (or delegate) responsibility for making financial decisions – may influence our development and retention of financial knowledge.

In this post, Derek Tharp – lead researcher at Kitces.com, and an assistant professor of finance at the University of Southern Maine – delves into the recent research on how financial knowledge may increase or decrease over time based on how a couple allocates responsibility for making financial decisions.

A recent study from Adrian Ward and John Lynch provides some interesting insights into how the divvying up of financial decisions among couples may influence financial decision making. Contrary to what many may expect, the authors found that the initial assignment of financial responsibility was not influenced by levels of financial knowledge at the beginning of the relationship. While this may seem counterintuitive, from an economic perspective, it is the individual with the comparative advantage (rather than the absolute advantage) that we would expect to take on a larger share of financial responsibility in an efficient outcome. For example, despite a CFO’s potential absolute advantage over a stay-at-home spouse’s financial knowledge, it may be the case that it is better for the household financially if the CFO focuses on their work rather than managing household finances. Because all households have limited time and resources, the reality is that some trade-offs in all areas of life are ultimately inevitable.

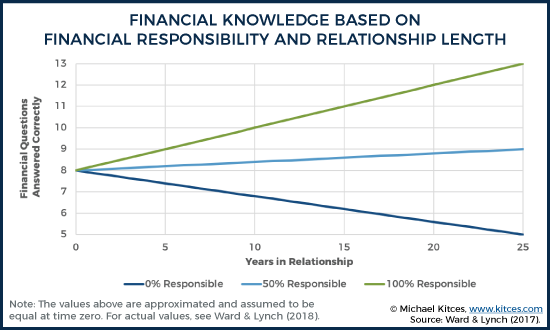

Long-term, the assignment of financial responsibility appears to influence financial knowledge, with spouses who take on 100% of the responsibility becoming most knowledgeable, whereas those who take on no financial responsibility (i.e., delegate those responsibilities to their partner) actually experience a reduction in their financial knowledge over time. Furthermore, while those who share responsibility do appear to each see modest knowledge gains with time, those gains are much smaller than the gains experienced by households with one member specializing in financial responsibility.

Overall, this finding has important implications, as it suggests that there is both risk and opportunity associated with sharing or delegating financial responsibility. On the one hand, those who delegate may benefit from the higher levels of knowledge gained by the specializing spouse. On the other hand, should the specializing spouse experience disability or premature death, a spouse with less financial knowledge than they may have had if they were involved in making financial decisions could be thrust into a role as a financial decision-maker without being prepared. Moreover, it’s possible that financial knowledge of those who delegate responsibilities to a financial advisor could similarly experience a decrease in financial knowledge over time. While this is not explored in Ward and Lynch’s study, it is nonetheless important for financial planners to help clients understand both the risks and rewards associated with divvying up responsibility between members of a household… and between a household and their financial advisor!

Knowledge Retention And The Challenge Of Financial Literacy Programs

An unfortunate reality of financial education is that we haven’t been able to figure out how to make their effects long-lasting. Financial education can boost financial knowledge in the short-run, but the benefits are still fairly small and tend to decay quickly.

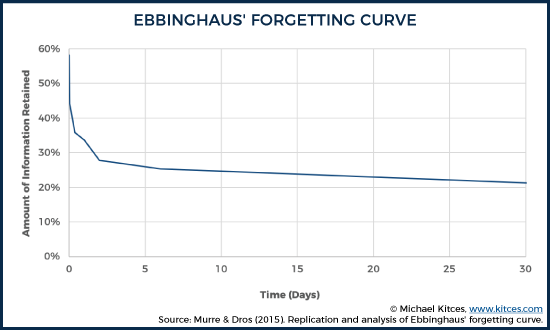

However, this is not unique to financial knowledge. In the late 1800s, psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus famously developed the first “forgetting curve” based on a study he conducted on himself by trying to memorize nonsensical words and seeing how many he could recall over time.

As you can see in the chart above, Ebbinghaus’ recall fell off quickly (a finding which has been replicated often – e.g., this 2015 study). The single biggest decline came from increasing the time before recall from 20 minutes to 1 hour, before fairly quickly beginning to reach a plateau that Ebbinghaus was able to maintain as long as 30-days.

This rapid decline in retention is why the idea of “just-in-time” financial education has risen in popularity – where the aim is to deliver education as close to the point of making a decision as possible (rather than trying to educate months or years in advance, at the risk that the knowledge won’t actually be recalled when it is relevant and needed).

And yet, while we have struggled to find educational programs which can effectively impart the long-term financial knowledge needed to help people make good financial decisions, that doesn’t mean that levels of financial knowledge may not change in predictable ways over time.

How A Couple’s Financial Knowledge Changes Over Time

A recent study by Adrian Ward of the University of Texas-Austin and John Lynch of the University of Colorado at Boulder examines how financial knowledge changes over time, based on how a couple allocates responsibility for making financial decisions between themselves.

Ward and Lynch examine this by asking respondents how long they have been in a relationship, how much financial responsibility they have, and a series of 13 financial questions designed to test an individual’s financial knowledge.

A few notable trends emerged in their results. First, a partner’s financial knowledge at the beginning of a relationship was not actually a factor in determining who took on financial responsibility at the beginning of a relationship.

While that may seem surprising at first, this is actually fairly consistent with standard economic theory, as it would be the partner with the comparative advantage rather than the absolute advantage who would be predicted to take on the responsibility. In other words, even if a partner is financially more knowledgeable (i.e., he or she has an absolute advantage in financial knowledge), that doesn’t necessarily mean they will be the partner with the most comparative advantage in taking financial responsibility. For instance, a household may be better off with a partner who is a CFO focusing on their work rather than managing the household’s finances, even if that same partner is the most financially knowledgeable (i.e., the costs in both time and effort of taking on such tasks may not be worth the benefits).

In support of this position, the researchers did find that relative demands on a partner’s time outside of the household, and relative contribution to nonfinancial household tasks, were correlated with financial responsibility. Additionally, other partner characteristics, such as gender, age, preference for having financial responsibility, and confidence in one’s ability to find financial information, were correlated with who took on the financial responsibility.

The caveat, though, as illustrated in the chart below, is that when one member of the couple takes on the primary financial responsibility role, he/she tends to become more financially knowledgeable over time (as they gain financial competencies), but the other spouse tends to become less financially knowledgeable over time (as whatever financial competencies or skill sets they may have had appear to deteriorate without use). In other words, when financial responsibilities are fully allocated to one partner and not the other, levels of financial knowledge diverge considerably over time, with the partner who takes on responsibility becoming increasingly knowledgeable, and the partner who delegates responsibility becoming increasingly less knowledgeable.

By contrast, among the households that do share responsibility equally (e.g., 50-50), there appears to be a slight upward trend in financial knowledge for each member of the couple. This too makes sense, as again people become more knowledgeable as they gain experience with financial topics over time, and when both members of the couple are financially involved, both tend to gain that experience and financial competencies.

Implications For Couples Divvying Up Financial Responsibility

These dynamics highlight some important implications – some fairly intuitive, and some less so.

Optimally Allocating Responsibility

The findings of Ward and Lynch have important considerations for the risk associated with allocating a high level of responsibility to a single partner: Should a household CFO become financially incapacitated – either due to death, disability, or divorce – then there is a chance that the remaining partner will then be thrust into the role of financial decision-maker, with a low level of financial knowledge and skills to take on that responsibility. Which perhaps isn’t big news for financial planners, particularly given the experience many advisors have had with a spouse who is left ill-prepared to take over the household CFO role.

Of course, with the exception of simultaneous death, all relationships are going to come to an end at some point. Which raises the question of whether households should allocate responsibility equally, in preparation for the inevitable?

Not necessarily. All households have to decide how they will allocate their scarce time and resources, and there’s no real reason to believe that a 50-50 allocation is inherently optimal (even given the subsequent risk when one spouse eventually leaves the picture, whether via death, disability, or divorce). In fact, given that one spouse almost certainly does have a comparative advantage, it is doubtful that a 50-50 allocation will ever be optimal!

The reason is that, like all other household decisions that involve trade-offs (spending vs. saving, work vs. leisure, outsource vs. do-it-yourself, etc.), there are both advantages and disadvantages to specialization. In fact, based on Lynch and Ward’s findings, it’s households with partners who take on 100% responsibility that have decision-makers who scored at the highest levels of objective financial knowledge. So assuming that higher levels of knowledge translate into higher levels of good behavior, it’s these households that do not split their financial responsibilities who appear to have decision-makers capable of making the best financial decisions!

Of course, that strategy works until it doesn’t, and then we’ve come full circle… As Nassim Taleb notes in Antifragile, redundancy can be an important way of managing risk. The human body has many redundancies built into it (two eyes, two kidneys, etc.) as a way of managing the risk that one of these vital organs is damaged. In some cases, these redundancies may be more than just a redundancy (e.g., two eyes provide better depth perception than one eye), but oftentimes our redundancies could be seen as sub-optimal in the sense that we burn extra energy running our “backup” systems. Perhaps a body with fewer redundancies could achieve higher levels of performance by some objective measure (e.g., higher maximum lifespan), but a lack of redundancies would mean higher variance as well, with more people dying prematurely and unable to survive on a built-in backup.

Of course, that strategy works until it doesn’t, and then we’ve come full circle… As Nassim Taleb notes in Antifragile, redundancy can be an important way of managing risk. The human body has many redundancies built into it (two eyes, two kidneys, etc.) as a way of managing the risk that one of these vital organs is damaged. In some cases, these redundancies may be more than just a redundancy (e.g., two eyes provide better depth perception than one eye), but oftentimes our redundancies could be seen as sub-optimal in the sense that we burn extra energy running our “backup” systems. Perhaps a body with fewer redundancies could achieve higher levels of performance by some objective measure (e.g., higher maximum lifespan), but a lack of redundancies would mean higher variance as well, with more people dying prematurely and unable to survive on a built-in backup.

So the point is not that there’s any such thing as a single “optimal” allocation, but rather, to acknowledge that household allocation of financial responsibility is a risk-reward trade-off just like so many others that household can make. Given a household’s unique preferences and characteristics, any allocation could potentially be reasonable.

Specialization With A Safety Net?

Notably, implicit to the discussion so far has been an assumption that higher financial knowledge results in better financial decision-making, which may not necessarily be the case. How the 13 questions used to assess financial knowledge in this study correlate with any number of specific financial behaviors is still very much unknown. It’s probably safe to assume that, all else being equal, more financial knowledge is generally better, but as Sandra Huston has noted, having financial literacy requires more than just having financial knowledge. One must have the ability and confidence to apply financial knowledge appropriately (and know when they can’t!), and concepts such as financial self-efficacy are incredibly important to making good financial decisions.

Similarly, we should consider that financial illiteracy is not the same as financial ignorance. There’s a big difference between someone who lacks financial knowledge and doesn’t have the confidence or ability to seek information or guidance and someone who lacks financial knowledge and does have the confidence or ability to seek information and guidance. The former could result in financial devastation, while the latter may have no negative consequences at all (particularly since one option is simply to hire a financial planner to help fill that void for the less-financially-knowledgeable spouse if/when the time comes).

As a result, focusing on a delegating spouse’s level of financial knowledge may be the completely wrong measure for determining which households are at risk in the first place. Having a plan for where a delegating spouse gets knowledge (or assistance), if needed, may ultimately be far more important.

Another notable implication is that the risk associated with concentrating financial responsibility with one spouse is not the same at all times across the lifecycle.

Consider, for example, a couple with a strong marriage that is at very low risk of divorce. If each spouse is currently 25, there’s about a 3.8% probability that a male spouse would die before age 50 and a 2.3% probability that a female spouse would do the same. So, the risk is real, but it’s small, and it’s fairly easy to manage with insurance (in the event of both death and disability). And it’s not clear that risk can’t be mitigated by promoting the self-efficacy needed to seek information or guidance, if needed, rather than splitting roles based on the perceived balance in financial knowledge.

Working With A Financial Advisor

On a related note, it would be interesting to see what financial knowledge measures look like for clients of financial advisors. Do they become more knowledgeable with time, perhaps due to the continuing education they receive from their advisor? Or, like the delegating spouse, do they both become less knowledgeable with time, as they increasingly rely on their financial planner to guide their decisions for them?

While this is pure speculation, we might suspect there’s a lot of variation by client type. True delegators, who find value in offloading responsibilities to a third party, may very well see a decline in financial knowledge after hiring a financial advisor. However, if delegating was their goal, that may not even a bad thing (so long as they’ve hired a competent professional!). On the other hand, validators who stay highly involved in their financial planning experience (e.g., the engineer who wants to know what type of distribution your Monte Carlo software utilizes), may very well continue to accumulate more knowledge when working with a professional (by learning from them through the financial planning process over time).

Additionally, it would be interesting to know how “financial responsibility” is reallocated after working with a financial advisor (or what people even mean by this in the first place). In a paper presented at the 2018 CFP ARC, Sarah Fallaw, Michelle Kruger, and John Grable used job analysis to define tasks related to personal financial management in the household. The researchers collected various tasks that a household CFO may have, based on prior studies, and ended up with a list of 280 unique tasks spanning four categories: planning (e.g., preparing a budget, investing, managing taxes), financial responsibility (e.g., ensuring security, generating revenue, monitoring), problem solving and decision-making (e.g., leveraging technology, outsourcing, researching), and working with others (e.g., donating, negotiating, financial mentoring).

Of the 280 tasks identified by Fallaw, Kruger, and Grable, many are such that it is impossible to allocate 100% of financial tasks to a third-party. So, after a household hires an advisor and everyone settles into their new roles, do spouses maintain knowledge in the areas they need to? Is time freed up to allocate towards new tasks that were being neglected? Allocated towards other areas, such as leisure? We don’t know the answers to these questions, as at this point it remains unclear whether hiring (and delegating responsibility to) a financial advisor mimics the pattern of delegating financial responsibility within a household, or not.

Allocation Risk Across the Lifecycle

Ultimately, the findings from Ward and Lynch are highly interesting and provide some potential insight into the risks (and rewards) that come from divvying up financial decision-making amongst members of a household.

Of course, it’s worth noting that the Ward and Lynch study is merely a correlational study. As interesting as their findings are, it’s not as if the observed divergence over time was the result of specific individuals being tracked over time to observe their financial knowledge accumulation or degradation. This limits some of the extra steps that can be taken to try and address “endogeneity," which includes a wide range of potential biases such as omitted variable bias, measurement error, simultaneous causality, and selection bias. For instance, it is possible there could be unique characteristics about those who select into roles at various levels of responsibility (e.g., someone who selects into a 100% role is likely different than someone who selects into a 50% or 0% role, in ways that are hard to fully control for). Therefore, we cannot truly say that it is the role selection that is causing changes in financial knowledge.

Nonetheless, the research is useful to begin to better understand how delegating financial responsibility within a household can impact the knowledge levels of the spouses over time. And within the context of potential changes in levels of knowledge after delegating at least some financial responsibility, the same sort of dynamics may be relevant to the relationship between a financial planner and their clients as well. Households who delegate responsibility to a professional may become more or less knowledgeable with time. We don’t have the data that would be needed to assess this question now, but, at a minimum, financial planners ought to help clients understand both the risks and rewards associated with divvying up responsibility between members of a household… and between a household and their financial advisor!