Executive Summary

"Save a healthy portion of your income every year from the start of your working years to the end" is a standard of retirement planning advice. Although we may debate about whether the exact number is 10%, 15%, or 20%, or more, the focal point is the same - as long as you save a sufficient portion of your income, you'll have enough savings to fund your retirement.

However, it can actually be even more effective to not save in the early years, and instead invest in one's "human capital" by trying to boost earnings instead of the retirement account balance. In order to make this work, though, it's crucial to keep future spending from rising as fast as future income.

Consequently, the reality is that maybe baby boomers are "behind" in their retirement savings not because they failed to save a percentage of their income, but instead because saving "just" a percentage of income allowed them to consume the rest and increase their spending to unsustainable levels. In turn, this suggests that in the future, the better path to retirement success may not be to save a flat percentage of income every year, but instead to target an appropriate standard of living, raise it conservatively, and save all the rest, however much that may be!

The inspiration for today's blog post was a recent conversation I had with another financial planner about an article I wrote a few months ago, suggesting that for young people, it might be wiser to invest in education that advances one's career rather than in a Roth IRA (at least once a basic emergency account is established). The basic gist was that with a lifetime of earnings potential ahead of them, even small increases in base earnings today can have a tremendously magnified effect over a lifetime - potentially producing a wealth increase more than 10X than of "just" a Roth IRA that compounds for decades.

What came up in our conversation, though, is that this approach doesn't merely potentially produce a far greater amount of lifetime wealth and retirement savings; it also produces a significantly "distorted" retirement savings pattern that is heavily loaded on the back end.

Comparing Savings Patterns By Starting Early Versus Waiting

For the "traditional" healthy retirement saver - we'll call him Jerry - the standard approach might look something like this: save 10% of income every year until retirement, invested in a balanced portfolio expected to earn 8% for the long run, allow the power of compounding to work for you, and you'll have a healthy retirement. Assuming the individual earns $50,000/year (increasing by 3%/year for inflation) and continues down this path for 40 years (from age 25 to 65), what starts out as $5,000/year of savings (on a $50,000 salary) finishes as $15,835/year of savings on a $158,351 inflation-adjusted salary. The accumulated account balance will have grown to a whopping $1.8M, which at a 4.5% safe withdrawal rate would produce about $25,000/year of income, sufficient to replace about 50% of pre-retirement income, a pretty healthy replacement ratio given that it doesn't even include Social Security benefits. (Of course, those who can save a greater percentage of income can generate assets to replace even more pre-retirement income.)

Now let's look at Jerry's sister Sally, who has a comparable income but saves no money for the first 10 years, reinvesting all the savings into training and courses in an effort to get an extra 5%/year boost in income. At face value, this doesn't seem like much of a deal - "spending" $5,000/year that won't enjoy 40 years of tax-free compounding in a Roth IRA, in exchange for "just" another few thousand dollars of salary each year. And in fact, the results don't look great; although salary after 10 years is about $100,000/year instead of only $65,000/year, resulting in annual savings of $10,000/year instead of only $6,500 by that point, the additional $3,500/year of savings just can't make up for being more than $81,000 behind in Roth IRA savings. By the end of the 40-year time horizon, Sally has just shy of 1.6M while Jerry is just over 1.8M, resulting in almost 15% less in retirement income.

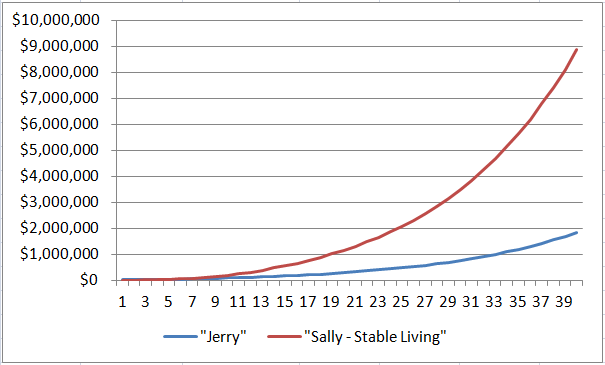

The comparison between Jerry and Sally's savings is shown in the chart below.

Comparing Retirement Living Standards

What's notable in comparing Jerry and Sally, though, is that by the end of the projection there is also a tremendous difference in the ongoing standard of living.

While Sally's higher annual savings in the later years couldn't make up for the shortfall of savings in her early years, by the end of the time horizon she is also earning a whopping $242,605/year instead of only $158,351. Consequently, while Sally comes up about $275,000 light in retirement savings, she is also taking home an extra $84,000 per year in ongoing income, more than 50% higher than Jerry!

While Sally may enjoy living it up for a while though, from the perspective of the soon-to-be retiree, this actually means that Sally will feel even worse off for retirement. While the accumulated $1.6M of savings can't even replace 50% of her original inflation-adjusted $50,000/year standard of living, it can't even replace 30% of her then-current standard of living in the final years before retirement! In other words, not only is Sally's retirement savings about 15% behind Jerry's, but Sally's standard of living has disproportionately risen to be almost 50% higher; thus, while Jerry has a modest shortfall (given "only" a 50% replacement ratio that could mostly be patched up by Social Security), Sally has what may feel like a catastrophic shortfall, and is far behind.

Getting Back On Track After Waiting To Save

The evidence above may suggest that reinvesting in human capital and career earnings is a bad deal. After all, Sally not only has less in retirement savings than Jerry because she failed to save in the early years when compounding has the greatest impact, but she also will feel like she faces an even more severe shortfall because her lower retirement savings is hopelessly behind in funding her far more expensive lifestyle.

However, the reality is that Sally's problem is not that she reinvested her earnings in the early years; the problem is that she spent so much of her salary increases in the later years. For instance, let's look at what happens if Sally takes her "excess" salary, and saves it; in other words, she tries to live the same standard of living that Jerry does all along, which means in year 10 when she's earning $100,000 while Jerry only earns $65,000, she still keeps on living like she's earning $65,000 and saves the rest. The results of this approach, compared to Jerry, are shown in the chart below.

Suddenly, the benefits of reinvesting in human capital become clear. While Jerry has just over $1.8M saved for retirement, Sally has $8.8M, allowing her to generate a whopping $400,000/year at a 4.5% safe withdrawal rate, even though it would take "only" $158,351/year for her to maintain the equivalent of Jerry's standard of living (which we assume she was doing all along). Because of Sally's dramatically higher income, she is saving almost $100,000/year in the final decade before retirement as she reaches her "peak earnings" level.

As a result, Sally enjoys more than double the income for the rest of her life, by deliberately choosing to save nothing for the first 10 years beyond her excess salary raises. Or alternative, if Sally merely decided that she would retire when her assets were sufficient to replace 80%-90% of her pre-retirement standard of living, she would have retired 10 years before Jerry.

The Key Is Spending, Not Saving

What this example ultimately illustrates is that the real key to a better retirement is not merely reinvesting into one's career and human capital in the early years, but to ensure that the individual's spending and standard of living do not grow as fast as the income does. Merely saving the same percentage of a higher income doesn't make up for investing in one's career and reduced savings in the early years, and in fact leads to an unfortunate trap because the standard of living by the end of the working years will have radically outpaced the savings that was, for most of the time period, set for a standard of living long since left behind in the dust.

In turn, this has several notable financial planning implications for clients, including:

- Don't just save a set percentage of income; instead, set a target spending level, and save all of what's left.

- It's ok to raise the standard of living over time as income rises (i.e., to set successively higher spending levels), as long as spending does not rise as quickly as income. Otherwise, you can't support the later years' standard of living on the early years' limited savings.

- The focus should be on spending, not saving. Telling Sally to save more money, once her lifestyle has acclimated to her new income levels, will be almost impossible. Instead, the key is to focus on spending patterns that will be sustainable in the first place, and save what's left.

- It's normal and expected for clients to have "peak savings years" in the final years before retirement. This does not mean the retiree is behind, it is simply the natural result of what occurs when income grows at a high real rate of return. In point of fact, the more rapidly that earnings rise, the more final retirement savings should be back-loaded in the later years.

- Investing into career can dramatically reduce the required level of ongoing savings. Jerry would have had to save 20%/year of his income to replace 100% of his standard of living in retirement. Sally allocated nothing to saving for the first 10 years, lived the same lifestyle as Jerry after his 10%/year of savings, and still ended out doubling her standard of living by the end.

In fact, when viewed from this perspective, perhaps today's "retirement crisis" is simply the result of normal income growth patterns for workers - and that the real problem is not that baby boomers didn't save enough in their early years, but simply that they allowed their spending levels to climb in pace with their earnings. In reality, when spending is held steady, savings rates should climb dramatically in the later years of retirement!

So what do you think?

Michael–What you’ve demonstrated is the value of not getting on the hedonic treadmill. Humans are subjected to psychological adaptation (explained by Dr. Edward Hagen here: http://www.anth.ucsb.edu/projects/human/epfaq/psychadaptation.html). As a simple example, if I buy a BMW this year, then next year, a BMW won’t be as appealing, and I’ll feel more inclined to buy a Mercedes, then a Lotus, then a Bentley, ad nauseum. James Altucher tells the story of the jealous $3 billionaire – he was jealous of the $15 billionaire (http://www.jamesaltucher.com/2011/10/the-six-diseases-billionaires-get/).

So, the crux of the matter is how to convince your clients to not hop on that hedonic treadmill. Part of the answer is in combating ego depletion. You get tired of saying “no” over and over again, as this Case Western Reserve University study shows – http://faculty.washington.edu/jdb/345/345%20Articles/Baumeister%20et%20al.%20(1998).pdf).

Showing number is important – it appeals to the logos of an argument, but there’s still a bunch of work to be done to get over the psychological hurdles which prevent us from living our lives out just as the charts predict we will – harnessing the ethos.

Maybe I missed it. Did we have Sally pay tax at her marginal rate on her excess salary?

Great post, Michael. I’ve written about this problem before and think about it a lot, and have concluded that if you want to succeed at keeping consumption in check without causing an intolerable level of “ego depletion,” your strategy is going to have to include two features:

1. Automate savings. I think everyone knows this by now.

2. Extremely conservative housing choices. If we were to examine Sally’s lifestyle in scenario 1 vs scenario 2, I expect we’d see that Sally #1 lives in a much larger house, probably has a second home, and has done plenty of expensive renovations. Sally #2, by the time she retires, has spent years living in housing that other people in her tax bracket would consider third world. This may cause a certain amount of stress, too, but at least you don’t have to decide every day how much to spend on housing.

That probably goes for cars, too, hence the “millionaire’s car” concept from Millionaire Next Door, but houses cost a lot more than cars.

This concept is painfully clear within my client base. I have many clients from two distinct backgrounds – call them “Group A” and “Group B.” For some reason, Group A tend to live much more modest lifestyles and save considerably more – despite earning far less than my Group B clients. On that other hand, Group B tend to live in larger houses, have nicer, newer cars, go on more expensive trips, constantly remodel – just as your article indicates.

The problem come sin when Group B is either laid off or attempts to retire. They experience the double-dip impact of a higher-cost lifestyle to maintain, as well as lower savings.

Unfortunately, it is often fait accompli by the time they become clients, because they have spent 25-40 adult years establishing this lifestyle, and there is little they can do to turn back. In some cases, clients that “get it” can make adjustments over time, typically by downsizing their retirement home, replacing cars less frequently, selling “lifestyle assets” (boats, RV’s, summer homes, etc.), etc. But it takes a lot of effort and coordination between spouses to turn back the clock like this.

Professor Kotlikoff from Boston University wrote a great book on this subject, which he labeled consumption smoothing. The book is Spend til the End.

And his software ESPlanner figures out exactly what people can spend/consume, in order to smooth their consumption over their lives. He has various levels of ESPlanner available to everyone, from the lay person through the advisor.

It has been my experience that expenses rise to meet income. It is hard enough to convince clients to save a percentage of their incomes, let alone try to get them to set a limit for their expenses. In an ideal world, this theory would work, but in reality, people will spend or borrow to achieve whatever they want whenever they want it. There will always be exceptions, but the more we make, the more we spend. Using similar reasoning is why budgets rarely work. If, however, you focus on the reduction of debt while simultaneously increasing investment, the result, which is a reduction in expenses, brings a client to point of living within their means, and achieving a more satisfied sense of accomplishment. There are too many intangibles to focus on with trying to control spending, and the process is more manageable trying to focus on investment and/or debt.

So Mike, do we need to trash Roger Ibbotson’s et al, famous report from April 2007 titled:

National Saving Rate Guidelines for Individuals at http://www.journalfp.net ?