Executive Summary

For the past several decades, RIAs have increasingly differentiated themselves and their advice from competing broker-dealers by the “best interests” fiduciary standard that RIAs owe to their clients, from outright marketing themselves as fiduciaries, to signing “Fiduciary Oaths” for clients (that other broker-dealers wouldn’t and couldn’t sign).

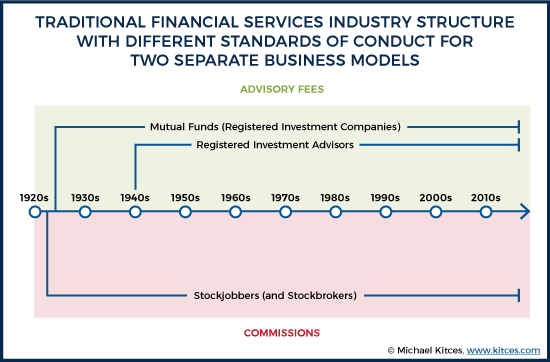

The fiduciary distinction for RIAs wasn’t originally intended to be a marketing differentiator for advice, though. Its roots lie in the fact that RIAs were created from the start to be providers of investment advice, while broker-dealers originally were created to play a vital role in the capital formation and capital markets process (which included selling investments, in the form of stocks and bonds to prospective investors, often underwritten by the broker-dealer’s investment banking division). For which RIAs were subject to a fiduciary standard – as the providers of advice – while broker-dealers were subject to a lower suitability standard consistent with the sales-centric role they were created to fulfill.

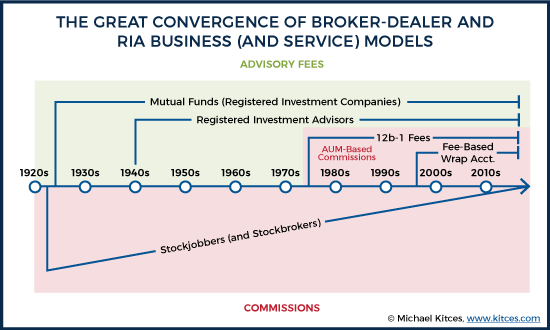

But over the past several decades, as technology has increasingly commoditized the core functionality of broker-dealers, from “discount” brokerage reducing the price to execute trades (without a stockbroker to facilitate them), to online platforms making no-load funds available to consumers directly (without a broker-dealer to sell them), the RIA and broker-dealer channels have gone through a Great Convergence. To the point that today, a consumer may pay 1%/year for ongoing financial advice in the form of a fee-based wrap account, a C-share mutual fund trail, or an advisory fee, and not even make a distinction between the choices. Except from a regulatory perspective, these remain substantively different choices, given the (originally) different roles that broker-dealers and RIAs play.

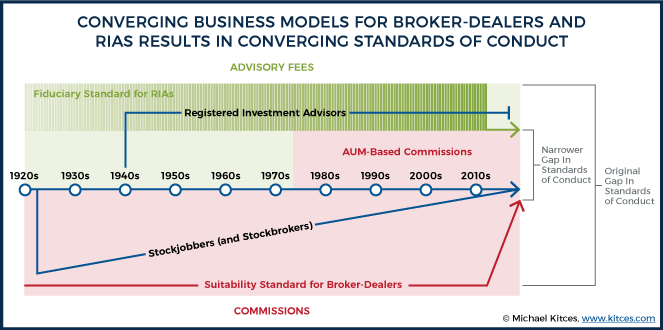

In recent years, the Great Convergence has led to a flurry of proposals on new standards, as regulators have recognized that as the gap between broker-dealers and RIAs has been reduced over the years, so too did the gap in the standards of conduct between them need to be narrowed as well. Resulting in the release earlier this summer of the SEC’s new Regulation Best Interest, lifting the standard of conduct for broker-dealers to a “Best Interest” standard when making a recommendation to their customers.

Notably, in practice, the new Best Interest standard under Reg BI is not a full-scale fiduciary duty and only applies at the time of the broker’s recommendation itself (and not to the overall relationship). Nonetheless, Reg BI will grant – and in fact, require – that broker-dealers now explain their standard of conduct as being an obligation to act “in the best interests of the customer when making a recommendation.”

Which leaves little room for RIAs to market their fiduciary obligation to act “in the best interests of the client” as a differentiator when broker-dealers will be able to use substantively identical words. Raising the question: how will RIAs differentiate themselves in the future?

On the one hand, some RIAs may point out that there’s still a difference between being a “fiduciary at all times,” versus "just" being held to a Best Interest standard at the time of recommendation alone. Others may pursue and highlight voluntary designations like CFP certification, which itself has its own “fiduciary at all times” obligation (applicable to not only RIAs but those at broker-dealers as well). Some may even choose to pursue new terms of distinction, like “stewardship” as a higher standard above merely being a legally-obligated fiduciary.

In the long run, though, arguably the best path forward for most advisors will simply be to actually differentiate on their services and what they actually do for clients, rather than their standard of conduct in the first place. As the irony is that, the more fiduciary advocates push for higher standards across the industry… the less likely it is that being a fiduciary with higher standards will ever be an effective differentiator again in the future.

The Great Convergence Of Broker-Dealers And RIAs: Closing The Gap In Standards Of Conduct

When the modern structure of financial services regulation was created in the early 1900s, broker-dealers and investment advisers were in substantively different businesses. Investment advisers (“investment counselors” at the time) supervised and managed investment accounts of clients, while broker-dealers and their “stockjobbers” (stockbrokers) were primarily involved in the capital formation and capital markets processes of facilitating the issuance of stocks and bonds and their subsequent trading (i.e., the literal securities-markets activities of brokering and dealing).

For which, accordingly, they had different business models (broker-dealers were paid by the transaction (i.e., commissions), while investment advisers were paid for advice), and also different standards of conduct (suitability for broker-dealer sales activity, and fiduciary for investment-adviser advice services).

But over the years, the evolution of the marketplace – and the evolution of technology – has driven multiple shifts in the services provided by broker-dealers.

In the 1970s, the de-regulation of fixed trading commissions for broker-dealers led to the rise of “discount” brokerage firms like Schwab and Ameritrade, leveraging their newfangled “computers” to drive the traditional human stockbroker out of business using technology and forcing broker-dealers to shift towards selling mutual funds instead (supported by the creation of the 12b-1 fee in 1980, allowing the broker to get paid ongoing servicing fees for the sale of those funds).

In the 1990s, the rise of the internet and the emergence of online brokerage firms started a shift away from broker-sold mutual funds, as consumers (rightly) began to ask “why should I pay a broker for a mutual fund that I can buy myself online without a commission?” (i.e., a no-load fund). Which in turn led the brokerage industry to the rise of wrap accounts, and a request the SEC to create an exemption for fee-based brokerage accounts in 1999 (also known as the “Merrill Lynch rule,” as the wirehouse was one of the leading proponents of the new exemption).

The end result of these shifts is that, today, an advisor typically charges 1% of a client’s investment accounts to provide upfront and ongoing financial planning advice, holds themselves out as a financial advisor/consultant/etc., and there’s hardly a distinction made between whether it’s a 1% wrap account, a 1% trail on a C-share mutual fund, or a 1% advisory fee. From the consumer perspective, it’s the same all-in 1% fee on average, for the same comprehensive advice offering.

Yet technically, the former two compensation arrangements (a 1% wrap account or a 1% trail on a C-share mutual fund) are simply alternative/levelized forms of commissions for product sales or ongoing transactions, and only the latter is actually technically a fee for advice. Which is important, because again, the industry applies different standards of conduct to the different channels, recognizing their (previously very different) services, where brokerage sales activity is regulated under a suitability standard, and actual advice is subject to a fiduciary standard.

Which means, in essence, the industry’s regulations weren’t created for the convergence of industry channels that has occurred over the past 50 years. The standards were written for a world where broker-dealers sold securities (literally, in the sales business), and investment advisers were in the advice business. Leading to a 2008 RAND study that found “investors typically fail to distinguish broker-dealers and investment advisers along the lines that Federal regulations define,” and as a result, consumers were generally unaware that “advisors” with similar-sounding titles could be subject to substantively different standards regarding the advice they provided and the solutions they recommended. A follow-up 2015 RAND study found that only 3% of consumers knew that RIAs were the only type of financial professional held to a fiduciary standard.

How Regulation Best Interest Narrows The Gap In Broker-Dealer And RIA Standards Of Conduct

Given the context of the Great Convergence of broker-dealer and RIA business models, and that they’re both increasingly in the business of financial advice, the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest was created to similarly close the gap in standards of conduct between broker-dealers and RIAs.

Recognizing, however, that the fundamental purpose of broker-dealers – in the capital formation and capital markets process – still remains, and is different than that of RIAs (which are in the advice business, primarily in the form of ongoing monitoring and management of portfolios). And that as a result, creating a single uniform fiduciary standard that applies for both broker-dealers and RIAs wasn’t necessarily appropriate, given the very real non-advice functions that broker-dealers still play (for which a fiduciary obligation just doesn’t fit).

Lifting Up The Suitability Standard For Broker-Dealers

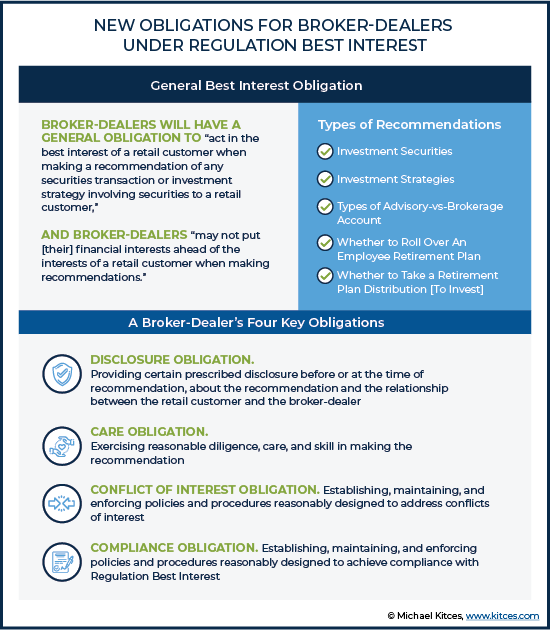

The General Obligation that Regulation Best Interest places on broker-dealers is that:

“A broker, dealer, or a natural person who is an associated person of a broker or dealer, when making a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities (including account recommendations) to a retail customer, shall act in the best interest of the retail customer at the time the recommendation is made, without placing the financial or other interest of the broker, dealer, or natural person who is an associated person of a broker or dealer making the recommendation ahead of the interest of the retail customer.”

Notably, a key aspect of the new “Best Interest” standard for broker-dealers is that it applies only at the time the recommendation is made, and not to the overall broker-dealer business model or its relationship to the client, recognizing that broker-dealers still fulfill many non-advice (non-fiduciary) roles in capital markets (e.g., principal trading, and more generally facilitating the distribution of securities to investors).

Nonetheless, when recommendations themselves are being made, broker-dealers will now be subject to four core Obligations to fulfill their new Best Interests standard:

- Disclosure Obligation. Providing certain prescribed disclosure before or at the time of recommendation, about the recommendation and the relationship between the retail customer and the broker-dealer;

- Care Obligation. Exercising reasonable diligence, care, and skill in making the recommendation;

- Conflict of Interest Obligation. Establishing, maintaining, and enforcing policies and procedures reasonably designed to address conflicts of interest;

- Compliance Obligation. Establishing, maintaining, and enforcing policies and procedures reasonably designed to achieve compliance with Regulation Best Interest.

With respect to the Conflict of Interest obligation, in particular, broker-dealers will also be explicitly required to, “Identify and eliminate any sales contests, sales quotas, bonuses, and non-cash compensation that are based on the sales of specific securities or specific types of securities within a limited period of time,” as well as “identify and mitigate any conflicts of interest associated with recommendations that create an incentive for a [registered representative] to place the interests of [themselves or their firms] ahead of the client.” (Though notably broker-dealers will not be required to mitigate their own conflicts of interest, but merely to disclose them.)

The end result of these changes is that – notwithstanding industry criticism to the contrary – Reg BI really does lift the standard of conduct for brokers from where it was. Not to a full fiduciary standard, but far closer than it previously was.

Did The SEC Lower The Fiduciary Standard For RIAs?

In addition to lifting the standard of conduct for broker-dealers, the SEC also (re-)interpreted more explicitly an RIA’s fiduciary duty as well. As the reality is that an RIA’s fiduciary duty isn’t actually defined in the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 in the first place.

Nonetheless, RIAs do have a fiduciary obligation to “eliminate or at least expose” (i.e., disclose) their conflicts of interest, stemming from the famous SEC v. Capital Gains Research Bureau Supreme Court case that formally established an RIA’s fiduciary duty as a part of its Rule 206(4) “anti-fraud” obligation that RIAs cannot be fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative in how they hold out to consumers.

Notably, though, one of the key distinctions of a traditional fiduciary standard is that conflicts of interest don’t just have to be disclosed and exposed; they are expected to be eliminated or mitigated, and only the unavoidable conflicts of interest are to be disclosed (because they can’t feasibly be avoided in the first place, and thus disclosed so clients can give informed consent is the only remaining option).

By contrast, the SEC’s explicit emphasis that RIAs have an obligation to “eliminate or disclose,” rather than an obligation to eliminate and disclose (disclosing where avoidance/elimination isn’t feasible), is a less stringent version of the fiduciary obligation for RIAs.

Accordingly, some (including the SEC’s own Investor Advocate) have raised concern that the SEC effectively lowered the standard of conduct for RIAs in its recent guidance by making it more of a disclosure-based standard that RIAs must eliminate or “just” disclose – perhaps not coincidentally, akin to the disclosure-based standard for broker-dealers under Regulation Best Interest.

Of course, the reality is that an RIA’s fiduciary duty really was very disclosure-based in the first place. Thus why, ironically, the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule – which was actually a more stringent mitigation-centric fiduciary rule – would have even banned a number of common RIA practices as being “too conflicted.”

Because, in practice, a wide range of conflicts of interest are already permitted for RIAs, as long as they’re disclosed in Form ADV. From charging differential fees for different asset classes (even when the RIA has discretion over the allocation, which means the RIA effectively has discretion over its own fees!). To even earning commissions through related businesses or entities. Thus why, several years ago, CNBC highlighted a list of the “Top Fee-Only RIAs,” only to have it turn out that 9 out of the top 10 were receiving insurance commissions in addition to their RIA fees. Which was entirely and "appropriately" disclosed those firms’ Form ADVs. But again making the point that the substantial conflict of interest - receiving insurance commissions pursuant to the RIA’s advice – was not actually a prohibited conflict of interest under RIA fiduciary rules… given that it had been disclosed.

Similarly, while many RIAs do highlight that they don’t receive any investment commissions as RIA fiduciaries, technically, this isn’t because the RIA fiduciary rules prohibit them from doing so. But simply because they don’t have a broker-dealer license to earn that commission in the first place. As if they did, earning advisory fees and brokerage commissions for product sales remains entirely permissible under an RIA’s fiduciary duty. Thus why there are so many hybrid advisors who are dual-registered with a broker-dealer and an RIA in the first place. In fact, the SEC Regulation Best Interest guidance even explicitly pointed out that in the case of dual-registered advisors, the RIA’s fiduciary duty extends only to the actual advisory accounts which he/she manages, while Regulation Best Interest (and more generally, the “broker” hat of the dual registrant) controls for the rest of the commission-based transactions that may occur.

Which means, in practice, the SEC’s interpretation of an RIA’s fiduciary duty may be less of a “weakening” of the standard, and more of simply a formal recognition of what it already was: a relatively "weak" disclosure-centric standard, at least as fiduciary standards go. Where many RIAs may have chosen to adhere to a higher version of the fiduciary standard – where conflicts of interest were in practice actively mitigated and not merely just disclosed – but that was a choice of the RIA, and not necessarily a reflection of the actual fiduciary requirement that applied.

Nonetheless, the end result is that just as the business models of broker-dealers and RIAs have converged – albeit not to the point of being identical, but at least very similar – so too have the standards of conduct for broker-dealers and RIAs now converged, again not identical but at least very similar, with broker-dealers being lifted up, and RIA fiduciary standards at least being “clarified” at the lower end of the fiduciary range.

The Death Of Fiduciary Differentiation Under Regulation Best Interest?

From a broad consumer perspective, the good news of Regulation Best Interest is that it really does lift the standard of conduct applicable to broker-dealers – not to a fiduciary duty that some consumer advocates had hoped, but a higher level than existed under the suitability standard, and with some newfound pressures to further reduce at least the conflicts of interest on brokers themselves (if not on their broker-dealer parent companies). The bad news, however, is that it will likely spell the death of fiduciary differentiation for RIAs themselves.

The reason, simply put, is that broker-dealers will now be permitted to market that they, too, operate “in the best interests” of their customers when making recommendations, as that is literally their new legal standard of conduct.

In fact, under the SEC’s own guidance, broker-dealers will be required in Form CRS to now state:

As a broker, dealer… When we provide you with a recommendation, we have to act in your best interest and not put our interest ahead of yours. At the same time, the way we make money creates some conflicts with your interests. You should understand and ask us about these conflicts because they can affect the recommendations we provide you.”

By contrast, RIAs will be required to state:

As an RIA… “When we act as your investment adviser, we have to act in your best interest and not put our interest ahead of yours. At the same time, the way we make money creates some conflicts with your interests. You should understand and ask us about these conflicts because they can affect the investment advice we provide you.”

Notably, the wording between the two about the standard of conduct and relationship to the client is almost the same. And that’s the point.

In the case of broker-dealers, the best-interest standard is technically limited to just “when providing a recommendation,” whereas the best-interest standard for investment advisers applies to the entire relationship (i.e., “when acting as your investment adviser”) in the first place.

Still, though, the plain-language wording of both is that each is subject to a “best interest” standard. For which the SEC didn’t even include the word “fiduciary” in the description of an RIA’s standard of conduct, noting that “some commenters, and results from investor studies and surveys, indicated that many did not understand the meaning of “fiduciary” or had never heard of the word. Accordingly, the modified standard of conduct disclosure both eliminates technical words, such as "fiduciary," and describes the standards of conduct of broker-dealers, investment advisers, or dual registrants using similar terminology in a plain-English manner.”

Beyond the remarkably-similar wording on Form CRS itself, the SEC has clarified that RIAs will still be permitted to separately use the word “fiduciary” to further explain their standard of conduct obligations in Form CRS, beyond the prescribed wording. Nonetheless, the point remains: going forward, broker-dealers can declare that they are subject to a “best interest” standard, in a similar manner to the required “best interest” wording that RIAs will be required to use as well.

Accordingly, the question for RIAs becomes: when in the summer of 2020, major broker-dealers start launching their new “We are obligated to act in your Best Interests” advertising campaigns to consumers, how will fiduciary RIAs differentiate themselves… especially when most consumers still don’t understand the legal jargon term, and when explained are told it simply means that RIAs are “obligated to act in your Best Interests” too?

What Comes Next After Fiduciary No Longer Differentiates?

Given these dynamics, the question becomes… what’s the next big differentiator for advisory firms after “fiduciary” no longer differentiates?

One option is to highlight what is still a difference in “Best Interest” standards, between broker-dealers who only have the obligation at the time of recommendation, versus RIAs who have the obligation with respect to the entire advisory relationship. In other words, the differentiator might not be “we’re fiduciaries subject to a best interests standard” but “we’re fiduciaries at all times

Another option will be to differentiate through professional designations, particularly ones like CFP certification that attach their own fiduciary standard, which similarly is an “at all times” fiduciary standard. In point of fact, broker-dealers like Edward Jones have already reportedly been considering whether to pull back from CFP certification, specifically because the CFP Board’s “fiduciary at all times” standard takes effect this October.

Which means voluntarily getting CFP certification, and subjecting oneself to the CFP Board’s fiduciary standard, effectively becomes another version of a “fiduciary at all times” differentiator. And one to which the advisor can then add “and I’ve actually gained the education and experience necessary to know what would be in your best interests and give the right advice” (as compared to the low Series exam educational requirements to obtain a FINRA license).

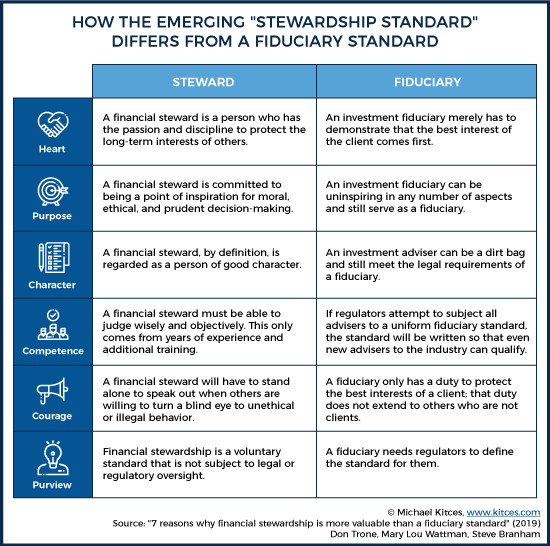

Some like fiduciary pioneer Don Trone have suggested that perhaps the leading vanguard of the advisor community will seek out and adopt a new term of differentiation to describe their scope and standard that leaves fiduciary behind, such as “stewardship.” As Trone explains it, “a financial steward is a person who has the passion and discipline to protect the long-term interests of others… while a[n investment] fiduciary merely has to demonstrate that the best interest of the client comes first.” Similarly, stewards have a sense of purpose and character (while fiduciaries just have to meet the letter of the law), have higher expectations of competency, cannot turn a blind eye (even on behalf of other non-clients), and similar to at least what fiduciary was in the past, is a higher aspirational standard that not everyone chooses to step up to (which in turn is what makes it differentiated from the rest).

On the other hand, one of the reasons why “fiduciary” in particular was so effective as a "voluntary" standard was that it was/is also a formal legal term, and not one that could be thrown around lightly by firms without risk of having the actual legal duty become attached. By contrast, “stewardship” may have aspirational meaning and historical significance… but it’s also a label the industry could readily adopt, and make it mean whatever they wanted it to mean. In other words, fiduciary “worked” for so long in large part because it was effectively a protected term that had legal significance under the law. (Which is why the industry effectively appropriated its significance by taking on their own “best interest” standard as well!) While “stewardship” has no such protections.

Of course, perhaps the most straightforward way for advisory firms to differentiate their services and value in the future is just to literally differentiate their services and their value, rather than the standard of conduct to which it applies. Arguably, the fact that RIAs so commonly differentiated on their fiduciary duty in the past speaks to how undifferentiated so many advisory firms are. Such that they have to differentiate by the standards of conduct that apply to what they do, rather than just differentiating by what they do.

Accordingly, the demise of fiduciary differentiation may only do more to stoke advisory firms towards other forms of niches and specializations, where they can actually more substantively differentiate a specific service for a specific target clientele… such that the standard of conduct is no longer a necessary path to differentiation in the first place.

Ultimately, it’s not hard to see why, even though Regulation Best Interest does increase the standard of conduct burden on broker-dealers, that the B/D community has in the end been supportive of the final Regulation Best Interest rules as “the best they could have hoped for."

As the SEC both declined to impose a full fiduciary duty on broker-dealers (which would have been even more disruptive), and handed the broker-dealer community the ability to market their own “best interests” standard for consumers, effectively undermining two decades of RIAs differentiating on their own fiduciary best-interests standard. Even as the SEC failed to specifically highlight in Form CRS the real difference in the two best-interests standards – that broker-dealers only have the obligation at the time of recommendation, while RIAs remain fiduciaries "at all times" (or at least, at all times when acting as an investment adviser, in the case of dual-registrants).

Sadly, though, the irony is that the entire discussion of Regulation Best Interest and the differential “best interests” standards between broker-dealers and RIAs would be a moot point if the SEC more stringently enforced the “solely incidental” exemption that allows broker-dealers to avoid being required to register as investment advisers (which would subject them to a fiduciary-at-all-times duty anyway). Yet instead, the SEC’s (re-)interpreted the "solely incidental" exemption to mean that a wide range of advice offered “in connection with and is reasonably related to the broker-dealer’s primary business of effecting securities transactions” is not subject to RIA standards in the first place.

Recognizing that, in practice, though, so many advisors at broker-dealers are in the business of providing advice (beyond just being incidental to the sale of brokerage products and services), a number of states, from Nevada to New Jersey to Massachusetts, have begun to propose or implement their own state fiduciary rules, subjecting any/all advisors in their states to a fiduciary duty, regardless of RIA or broker-dealer. Raising the question of whether the future will still be fiduciary, but simply driven at the state level instead of by the SEC.

Yet even if the future of a fiduciary duty for advice is a state obligation instead, the endpoint remains the same: as fiduciary advocates win the battle to lift the standards of conduct on broker-dealers providing advice, the very nature of differentiating as a fiduciary is no longer as relevant as it once was. And while Regulation Best Interest itself isn’t a full fiduciary duty, it is still close enough to greater undermine any perceived differentiation by consumers in the standards of conduct between broker-dealers and RIAs. Or stated more simply, advisors may be winning the fiduciary war, but the marketing plan of fiduciary differentiation is (as one would expect) being lost in the process.

And so the question remains: what will be the next differentiator of advice if “fiduciary” alone will no longer be a feasible way for advisors to differentiate in the future?

So what do you think? Are you a fiduciary who is concerned that broker-dealers marketing a “Best Interests” standard will undermine your marketing? How do you plan to differentiate your services in the future? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Michael

is right that Reg BI is the dawning of a new era for independent, fee-only

RIAs. Sales talk supported by corporate advertising will claim that brokers now

offer a “new and improved” standard that is higher than the RIA standard. BDs

are already sending this message. Recall the ad campaign, with Ringo Starr,

“This is not your father’s Oldsmobile.” It’s coming. Yet he’s wrong that Reg BI

guts fiduciary advice as a differentiator for independent, fee-only RIAs. In

fact, the opposite is true. Independent, fee-only RIAs’ best differentiator is

what they do as fiduciaries that brokers can’t. Showing this difference is the

challenge. For a discussion go to the Institute for the Fiduciary Standard

website here.

https://thefiduciaryinstitute.org/2019/07/25/in-a-reg-bi-world-is-fiduciary-differentiation-dead

I think that a significant differentiator should be the knowledge base of any advisor. Only memorizing the facts needed to pass a few of the Series exams, hardly prepares a BD to even know what is truly in the best interest of their clients. On a transactional level, BDs will likely be repeating the sales pitch that was presented to them by someone in their firm, where now I assume certain target client criteria will be added. If clients falls into that target box, shoving the security into their account can be considered in their “best interest”. But if you’re not looking at or don’t even know about the universe of possibilities, how can you really claim what you are doing is in someone’s best interest.

While both BDs & RIAs provide different but valuable benefits to clients, the SEC has made things much more confusing for the public. Eliminate confusion by eliminating dual registration. You’re either a BD/RR or a RIA/IAR. Clearly define & disclose in writing the benefits & conflicts of each type of firm (with RIAs required to reasonably eliminate conflicts). Make RIAs truly “fee-only” & prohibited from accepting ANY 3rd party payments (but allowed to accept SOME service benefits from custodians).

So a bd only has to act in their clients best interests when giving advice. What can they get away with when they are not?