Executive Summary

With an ever-increasing number of seniors afflicted with dementia, most financial advisors should expect to have to deal with (if they don’t already) clients experiencing diminishing mental capacity. Which are often challenging situations to deal with, not only for the complexities of the clients themselves, but also because client privacy rules can limit an advisor’s ability to involve other family members or to intervene if outright elder financial abuse of the diminished-capacity client is discovered. And while there has been regulatory progress towards protecting seniors from abuse (and allowing advisors more ways to involve family members and outside providers), it can still be very challenging for advisors to figure out how best to handle these relationships.

Importantly, though, financial advisors are in the unique situation of potentially being among the first to recognize that symptoms of diminishing capacity ailments are beginning to develop in the client, as indications of impaired financial capacity may be noticeable long before a formal diagnosis of dementia is made. Furthermore, given that seniors with diminishing mental capacity are potentially the most vulnerable to financial exploitation, it’s especially important for financial advisors to be aware of these risks, and to know what to do if they suspect (or know) that their client is being victimized.

In this guest post, Steve Starnes, a Principal with Grand Wealth Management in Grand Rapids, Michigan, discusses what client diminished capacity actually entails, how regulations protecting seniors (as well as guidance for advisors who serve them) have progressed, the importance of documenting goals, key relationships, and investment plans, and how advisors can help clients manage through the various stages of cognitive decline.

As a starting point, the most basic challenge is simply understanding the relatively vague nature of what ‘diminished financial capacity’ actually means… both for clients (and their loved ones) as well as the advisors who serve them. As while it’s easy enough to peg a definition on the term, the real challenge is in recognizing when the client has actually crossed the threshold of their financial capacity diminishing to the point that it actually becomes a real ‘problem’ where action must be taken.

The regulatory landscape paved by Federal legislation, FINRA regulations, and the North American Securities Administrators Association (NASAA) offers another challenge to advisors, who, in the past, were often restricted in involving authorities, but now in some cases may instead be required to report suspicions of financial exploitation. Fortunately, at the Federal level, the Senior Safe Act provides some level of immunity to advisors who report incidents of potential financial exploitation against seniors. NASAA is on the same track at the state level, encouraging states to adopt its Model Act which also grants advisors immunity for reporting suspected financial exploitation. Further, NASAA’s Model Act also allows for advisors and broker-dealers to delay disbursements from a client’s account if they suspect their client is a victim of financial exploitation. And when it comes to brokerage firms themselves, FINRA has established two rules intended to help broker-dealers protect customers from financial exploitation: Rule 4512 requires brokerage firms to request Trusted Contact Person information for customer accounts, and Rule 2165 allows brokerage firms themselves to put a hold on disbursements if financial exploitation is suspected.

Working with clients with diminished mental capacity creates additional concerns over the business risks faced by advisors and their practices. For example, if a client makes an uncharacteristic request, it’s often hard to distinguish whether the request is the result of a temporary external situation, or if it’s a warning sign of diminishing mental capacity… raising questions of how the advisor should respond and handle the client’s request (or not). The risks inherent in such situations, however, can be mitigated by implementing and following structured processes and procedures that a firm establishes in advance specifically for situations of potential diminishing capacity of clients. Among the most important are documenting (and regularly updating) client goals, values, and investment plans, as well as maintaining a list of their important personal relationships (including the client’s financial power of attorney, the advisor’s trusted points of contact, and custodial trusted contact persons) and getting signed permission in advance for the firm to be able to reach out to the client’s trusted points of contact if a concern of diminishing capacity arises.

Often the biggest advisor challenge, though, is simply the dynamic of trying to communicate with clients who can’t remember basic, yet important, details about their own lives and financial situations. By keeping conversations straightforward and clear, and maintaining patience and compassion during these conversations, client interactions can often remain productive and helpful. If the client’s financial POA is included in the discussion as well, they can help the client understand any confusing points of the discussion, and they may be better positioned to understand the issues around the client’s financial priorities.

Ultimately, the key point is that while there are many unique challenges in working with clients suffering from dementia, advisors have an abundance of resources available to help them navigate through these challenges. And arguably, advisors have an even greater responsibility and duty to clients who may be especially vulnerable to financial exploitation to help protect them to the fullest extent possible. The starting point, though, is to recognize that while financial advisors are typically well-equipped to help clients plan for their retirement, investments, and tax strategies, it’s equally important to create the necessary processes and procedures to plan for what unfortunately is a virtually inevitable reality of at least some clients who will eventually face the onset of diminishing mental capacity and who will need to rely on their financial advisor more than ever.

Do you have clients who are experiencing cognitive decline? Almost every financial advisor does.

This is not a new challenge, either. My grandmother had dementia and started declining around the time I became an advisor several years ago. I was so glad I was there to help her, so she and my mom—her primary caregiver—didn’t have to worry about money. This early experience shaped the rest of my career, including the substance of a 2016 article I wrote for Financial Advisor. In it, I proposed it is both an advisor’s duty and privilege to protect our clients who are facing cognitive decline in increasing numbers:

“I’m not saying this to demoralize you, but to inspire you—because I believe there is a solution in sight. In a word, that solution is innovation. And I believe that the best way to innovate is to do what we advisors already tend to do best during problem resolution: We coordinate and converse with everyone involved—from caregivers and fellow professionals to the seniors themselves.”

Not only are we advisors uniquely positioned to help families preserve their wealth when diminished mental capacity strikes, we’re also often on the front lines of the defense, being in a position to notice symptoms very early on. At least one research study examining declining financial capacity suggests that difficulty managing personal finances is one of the first symptoms many people exhibit in the early stages of dementia.

This means clients may be putting their financial security at risk or falling victim to fraud even before others recognize the problem, and so it’s imperative for advisors to know what to look for in clients of all ages, and consider what they will do if they are concerned about a client who they suspect may be suffering from diminishing mental capacity.

Financial advisors help clients navigate and manage many risks throughout their lives, including investment risk and income protection. Diminished mental capacity to manage their finances is another such risk, and in many ways, planning for it mirrors the planning at which we already excel. That being said, diminished financial capacity presents some advisory challenges all its own:

- Lack of a Clear Definition. The terminology itself can be vague and ill-defined. What is diminished capacity? How does it differ from dementia … or does it?

- Regulatory Risks. The legislative landscape is confusing, and evolving fast. What should you do, and what shouldn’t you? What can you do, and what is prohibited?

- Business Risks. For starters, it is difficult to advise clients who don’t remember conversations or follow through on advice. Or what if you ignore signs that there is a problem, and act on a client’s otherwise-concerning request? What are the risks if you don’t act on or at least want to refuse a client’s request? Wrong moves can put your practice at risk.

- Relationship Risks. Dementia impacts the afflicted individual, their family members, friends, and colleagues, with emotions often running high. Moreover, you, as the client’s advisor, can be the equivalent of a ‘first responder’, and may notice early signs of dementia, even before your client or their family have. How do you proceed? How do you frame the conversations?

In short, how do you determine where your role as trusted financial advisor begins and ends in a client relationship, and how do you manage the professional risks involved when advising clients with diminished (or diminishing) capacity? Again, this is no theoretical exercise; given the number of client relationships a typical advisor has, it’s a virtual inevitability for every advisor in the coming years as that entire base of clients continue to age.

While many advisor-oriented articles focus on managing cognitive decline as a compliance concern, I would instead suggest shifting the outlook to a more motivating focus. So even though it’s important to know the rules of engagement and how to comply with them, it may be most useful to frame your client relationships around the question, “How do I simply make sure I do the right thing for my clients, throughout our lifelong relationship?”

This shift may make it easier to integrate your strategy for working with clients’ cognitive decline into your normal policies and procedures. Just as it’s natural to have procedures in place for speaking to your clients about such topics as college funding, retirement planning, risk management, and legacy goals, you should also establish a process for helping clients consider the impact that cognitive decline and other long-term support needs may have on their financial well-being.

Defining Diminished Capacity

Rather than talking about the negatives of ‘diminishing capacity’, let’s proceed from a more positive perspective and start with a definition of ‘financial capacity:’

“Financial capacity” is generally defined as “the capacity to manage money and financial assets in ways that meet a person’s needs and which are consistent with his/her values and self-interest.”

This seems simple enough, but it’s often hard to identify the point at which someone’s financial capacity starts to decline. Perhaps among the most challenging aspects of managing diminished capacity is accepting what ‘it’ is. After all, numbers don’t lie when an investment portfolio is out of balance, or a budget is out of whack. But identifying cognitive decline is a much more slippery slope.

Consider this following example:

Alice, an elderly client, calls my office and wants to withdraw $15,000 from her portfolio. Alice is a sweet, 80-year-old widow with whom I have worked for many years. It seems odd to me that she does not remember making the same request two days ago. She seems in a hurry, and says a repairman is standing in her kitchen asking for payment. Alice also seems confused as she tries to explain what work was done. Several things concern me, especially the person in Alice’s kitchen, the seeming urgency, and the sum of money requested for ‘just’ a handyman repair. I ask myself whether Alice is showing normal forgetfulness, or if her forgetfulness and confusion are a sign that something else is wrong?

Some modest loss of financial capacity can be expected as a normal part of aging, as supported by many research studies that have shown financial capacity tends to decline with age. (Interestingly, another study found that confidence in financial decision-making actually increased with age, and common sense would dictate that, taken together, these two trends could be correlated with a higher risk of being scammed and abused! Or at the least, that it takes an outside trusted source – like a financial advisor – to help us realize that we may not be as sharp as we used to be.)

Notably, though, there is a difference between a modest, age-related decline in financial capacity, and a medical syndrome like dementia that causes physiological problems with memory, thinking, and behavior. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 50 million people suffer from dementia, with nearly 10 million new cases every year. While it is often caused by deterioration of or damage to the blood or nerve structures of the brain, the most common cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s, which is estimated to be the cause of up to 60-70% of dementia cases. Overall, Alzheimer’s affects 10% of people age 65 and older, and approximately 33% of people age 85 and older.

Regardless of its cause, dementia almost always involves progressive cognitive decline, which means that you cannot pinpoint precisely when or how the disease will progress, but that it will become steadily worse with time. In fact, the evidence regarding long-term outcomes is sadly and disarmingly clear:

Dementia (including Alzheimer’s) causes a person's ability to remember, understand, communicate, and reason to gradually decline. The symptoms will never improve; they will only get worse.

This is a difficult (heartbreaking!) but defining reality. And while it might be comforting to presume that early signs of dementia represent a temporary setback versus the beginning of a long, inevitable decline (because optimism is usually considered a healthy outlook), the reality is that it may be a dangerous (self-)deception that can interfere with the essential, critical planning that should be completed before someone’s financial capacity has disappeared for good. We should unfortunately but foreseeably expect that a person with dementia will inevitably lose financial capacity.

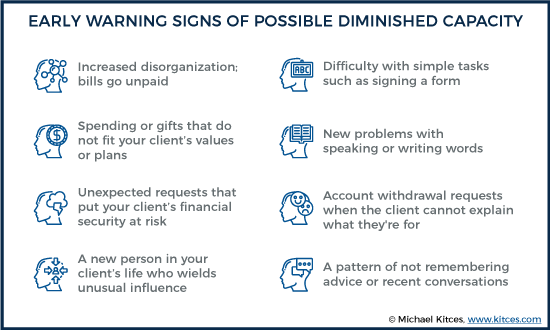

So, how should you as a financial advisor know if the signs you see are normal aging, or early signs of dementia? Financial advisors can’t be expected to do full-scale cognitive screenings as a medical professional would, and shouldn’t attempt to. Still, though, advisors can identify potential warning signs, and then take steps to address concerns, including recommending that the client see a doctor for a more formal evaluation.

For a client diagnosed with dementia, there are three broad stages of cognitive decline: Mild, Moderate, and Severe. A client’s pace of decline can vary greatly. On average, people age 65 and over live 4-8 years after diagnosis, though some do live much longer. However, it is important to remember that financial capacity often starts to decline many years before a formal dementia diagnosis.

(Editor’s Note: These various stages of decline are discussed in more depth in Steve Starnes’ December 2010 Journal of Financial Planning piece, “Is Your Firm Prepared for Alzheimer’s?”)

On The Regulatory Front Of Diminished Capacity: Safeguards And Opportunities For Improvement

It is great to see progress being made to provide more regulatory protection for seniors, and guidance for the financial advisors who serve them. This means if you want to try to do the right things to protect your clients, you have some opportunity to do so. Practically speaking, though, it is difficult to keep up with which rules apply to whom, and how to actually follow those rules to protect clients. Advisors and custodians alike must traverse a narrow course when acting on warning signs that a client might no longer be thinking clearly, balancing the interests of serving and protecting the client alongside the advisor’s obligation to maintain client privacy.

And liability exposure exists, regardless of whether you do or don’t follow your client’s requests:

- If you do follow an incompetent client’s request. You could be found liable if you act on a client’s request, and it can later be determined you did not have policies and controls in place to protect clients from requests they made that they didn’t have the mental capacity to

- If you don’t follow a healthy client’s request. With a duty of loyalty to our clients, we must typically do as they say (or unwind the relationship if we cannot do so in good conscience). Similarly, our clients’ account custodians cannot simply refuse to transact a properly submitted request.

As we’ll cover in the next couple of sections, there are best business practices as well as communication tools to help you protect your clients, yourself, and your practice. There also are legal protections you and your clients’ investment custodians should have in place — well in advance of needing them.

Additionally, there are key individuals you’ll typically engage with intermittently when a client is healthy and independent, and with increasing regularity if your client has diminished capacity. In many cases, the same individual(s) may fulfill one, two, or all three of these roles, but there should be a clear understanding of who in the family (or elsewhere) will fulfill each role.

- Client ‘Advocates’ with Financial Power of Attorney (POA). Once, several years ago, I was meeting with one of my older clients, a widower ‘Robert’, and his son ‘Brian’. Robert was healthy, but even so, he had given Brian financial power of attorney. “I consider Brian to be my advocate, just in case,” said Robert.This made so much sense to me that I decided to use the term ‘advocate’ ever since. When a client is healthy, a trusted advocate can be helpful in a pinch. If your client develops dementia, this advocate can become absolutely and increasingly essential. A financial power of attorney empowers your clients to authorize when and how their advocate (as their agent) can make fiduciary financial decisions on their behalf, for all things financial. Your client’s advocate might also be named as a trustee or successor trustee in your client’s estate plan.

- Advisors’ Trusted Point(s) of Contact. Beyond the formal role of the advocate with financial POA, your clients may have other individuals in their life they would like to authorize you, their advisor, to interact with in case of emergency (or concern about their mental capacity). You should ask clients to authorize these trusted points of contact in writing, including for what reasons the people named can be contacted without violating client privacy.

- Custodians’ Trusted Contact Persons (TCPs). The foregoing roles of client advocate and the advisor’s trusted point of contact are not to be confused with the regulatory-defined Trusted Contact Person (TCP) for a brokerage account holder. The SEC approved the role of TCP as a relatively new line of defense as part of a FINRA Rule 4512 amendment, which requires brokers to encourage account holders to name a trusted contact who custodians can contact if they believe an account holder is being financially exploited.A TCP does NOT have power of attorney, but as described in this FINRA FAQ, custodians are authorized to talk to the TCP, and potentially delay disbursing funds from an account “where there is a reasonable belief of financial exploitation.” It’s important to note that while your client’s account custodian is authorized to reach out to a TCP as described, the authorization does not extend to you, the advisor. Separate paperwork of your own is recommended – even if the brokerage account’s TCP is the same individual as the advisor’s trusted point of contact – following the guidance as described above.

The Senior Safe Act: A First Step

Regulators have taken note that custodians and advisors need their help to manage both client privacy concerns, and liability risks when acting in good faith to advise clients who are experiencing diminished capacity.

The Senior Safe Act, enacted on May 24, 2018, represented a significant step forward for seniors (who, as defined by this act, are individuals who are “not younger than 65 years”). For investment advisers and other “covered financial institutions,” the Act “provides immunity from liability in any civil or administrative proceeding for reporting potential exploitation of a senior citizen.” It includes individual as well as institutional immunity, and specifically describes that the immunity “can be helpful when a firm wants to report potential exploitation but fears that the report could violate a privacy requirement.” Employees who serve in a supervisory, compliance, or legal function in a covered financial institution are also eligible for immunity.

To obtain immunity, two requirements must be met: 1) employees must first receive appropriate training on how to identify and report exploitation before a report is made, and 2) reports of potential exploitation must be made “in good faith” and “with reasonable care.”

For example, if your client has a new friend in their life who seems to be taking financial advantage of them, you may report this suspected abuse to appropriate covered agencies. If you had received the requisite training prior to making the report, and honestly believed that the ‘friend’ had the intent to defraud your client, you would be eligible for immunity under the Senior Safe Act.

So far, so good. But gaps remain. The Senior Safe Act only provides immunity for contacting a “covered agency,” such as a Federal or state regulator, FINRA, or a state or local Adult Protective Services agency. It explicitly omits protection for conversations with third parties. And yet, trusted friends or family members may be ideally positioned to team up with you and your client as your client’s condition deteriorates. This means the Senior Safe Act alone isn’t enough to support financial advisors who want to involve other family members as a first (or alternative) line of defense for clients with diminishing capacity.

Furthermore, the Senior Safe Act defines seniors as age 65 or over. What if your client has dementia, but is not yet a senior citizen? Approximately 5% of people who develop Alzheimer’s do so before age 65. For them, the advisory firm would need other/additional policies and procedures to protect them beyond the limited scope of the Senior Safe Act.

FINRA Rules 2165 And 4512: Trusted Contact Persons (TCPs) For Brokerage Accounts And Preventing Distributions Due To Financial Exploitation

This circles us back to the importance of your client’s establishing appropriate POA agents, trusted points of contact you are authorized to contact as a financial advisor, and custodial TCPs early on in your advisor-client relationship—and to keep these contacts current over time. Even if your client never suffers from dementia, these relationships can strengthen your client’s base of support. And if your client is diagnosed with dementia, they will best position you to continue serving your client’s best interests during their decline.

According to FINRA Rule 4512(a)(1)(F), effective February 5, 2018, FINRA members are required to make reasonable efforts to obtain the name of a TCP for customer accounts. The “reasonable effort” requirement can be met simply by asking the customer to provide the information. And even though they may be required to ask for a TCP, they may still open a brokerage account if they don’t obtain a TCP.

If a TCP is named, then what can be done with it? FINRA Rule 2165, also effective February 5, 2018, allows, but does not require, brokerage firms (which would include an RIA custodian providing brokerage services to the firm and its clients) to put a hold on disbursements if financial exploitation of a specified person is reasonably suspected. A specified person is “(A) a natural person age 65 or older, or (B) a natural person age 18 or older, who the member reasonably believes has a mental or physical impairment that renders the individual unable to protect his or her own interests.”

A hold can initially be placed for 15 days on a disbursement, pending a brokerage firm’s investigation of potential financial exploitation, and can be extended an additional 10 days if facts and circumstances support the initial concern.

For purposes of Rule 2165, the term “financial exploitation” means: “(A) the wrongful or unauthorized taking, withholding, appropriation, or use of a Specified Adult's funds or securities; or (B) any act or omission by a person, including through the use of a power of attorney, guardianship, or any other authority regarding a Specified Adult, to: (i) obtain control, through deception, intimidation or undue influence, over the Specified Adult's money, assets or property; or (ii) convert the Specified Adult's money, assets or property.”

As currently in place, though, Rule 2165 also has a couple of important limitations:

- Distributions Only. Notably, only distributions out of brokerage accounts are restricted. FINRA is currently seeking input about extending the rule to restrict other transactions beyond distributions, such as trading and implementing (questionable) changes to the portfolio.

- Exploitation Only. Rule 2165 really only applies to suspected exploitation. Remember that a person with diminished financial capacity also has a higher risk of poor financial judgement, so Rule 2165 doesn’t apply if the concerning disbursements are being directed and authorized by the client themselves and not in a financial exploitation context (e.g., they’re simply being financially irresponsible for themselves due to dementia). For example, I previously worked with a client who started requesting substantial recurring unsustainable withdrawals because she was redecorating her house every month. I suspected diminished capacity, but I did not suspect exploitation, and thus Rule 2165 would not have applied to prevent the problematic distributions.

We are still in the early stages of custodial implementation of the Senior Safe Act, updated FINRA rules for Trusted Contact Persons, and preventing disbursements associated with financial exploitation. It would be helpful if custodians provided a person named as a POA some flexibility to place restrictions on retirement accounts as well, to prevent a client with dementia from making potentially very expensive mistakes.

Practically speaking, however, firms are not yet in the habit of identifying exploitation or diminished capacity and addressing them. And sadly, as common as financial exploitation and dementia are, it is still uncommon for cases of financial abuse among elders to be reported.

Still, though, brokerage firms will hopefully begin more frequently to take advantage of the new flexibility they have to protect clients.

(Limited) SEC Oversight With Respect To Protecting Seniors

While the SEC approved the FINRA rules discussed above, the SEC does not have specific statutes of its own for protecting seniors, defined as individuals age 62 and older (in contrast to the Federal Senior Safe Act, which defines seniors as individuals age 65 and older).

There is good news though. Through its exam process, the SEC is increasingly reviewing policies and procedures for protecting senior clients. Accordingly, the SEC recently examined over 200 firms “that had significant exposure to senior clients,” specifically looking at whether these firms had trusted contacts on record, how concerns about diminished capacity were addressed, and how beneficiary changes were handled. And notably, the SEC found that only a third to half of the firms had policies and procedures to address many of these issues. Unfortunately, for those with written policies, they were often not well-tailored to the firm’s business model. In other words, they were boilerplate policies, with a lack of clarity on how to apply them to practical situations.

In 2019, protecting seniors remains a priority for SEC examiners. Among the questions being asked by SEC examiners now are:

- How are seniors defined in firm policies and procedures?

- How are accounts for retirees monitored?

- What policies are there to protect clients with diminished capacity?

- What procedures are there to contact a trusted point of contact?

- What scrutiny is given to beneficiary changes?

- What training is provided to employees?

NASAA Model Act To Protect Vulnerable Adults From Financial Exploitation

An advisor’s specific state’s laws are important to understand as well, as states increasingly have taken their own role in protecting their citizens from financial exploitation or related concerns of diminished capacity.

For instance, many states have adopted the North American Securities Administrators Association (NASAA) Model Act to Protect Vulnerable Adults from Financial Exploitation, or some version of it. In its model form, the act allows investment advisors and broker-dealers to pause disbursements when financial exploitation is suspected. It also provides immunity if the advisor reports suspected exploitation to authorities, as well as to third parties the client designates (in contrast to the Senior Safe Act, which provides immunity for reports only to authorities or regulators but not other third parties like family members).

The NASAA Model Act further requires mandatory reporting to adult protective services and regulators when exploitation is suspected. Under state law, many professionals—such as doctors, nurses, social workers, and others—are commonly required to report abuse. NASAA is encouraging this for broker-dealers and investment advisors as well. Some states have adopted this mandatory element, while many others have revised it to “permit” rather than require reporting. You should clarify with your compliance advisor what is required in your state.

The bottom line is that it is increasingly common for state laws to encourage—if not require—reporting of suspected exploitation to both authorities and trusted parties. And the NASAA Model Act, while not adopted in all states, arguably does so to an even greater extent than current Federal legislation (e.g., Senior Safe Act) or recent FINRA Rule 2165.

Taking Care Of (Advisor) Business While Serving Clients With Diminishing Capacity: Process, Process, Process

Whether or not further regulatory clarifications are provided, you can best serve yourself, and your clients, by aspiring to this very simple, but powerful ethical standard:

If there are reasonable steps we can take to protect clients, we should take them.

In other words, it’s not just about compliance alone, although obviously complying with applicable state and Federal mandates matters as well.

The good news, though, is that there are many reasonable steps you can take in your everyday work with clients to improve decision-making for all concerned, and still be in adherence with applicable regulations. So, let’s shift our focus from the daunting challenges to their most plausible solutions.

I would suggest that processes and procedures are an advisor’s best friends for addressing nearly all the challenges related to guiding yourself, your business, and (most importantly) your clients through the minefield that is investment management and financial planning during cognitive decline. Start by asking yourself what controls you have in place to protect clients from harm caused by themselves or others.

What follows are the recommended building blocks that can be used regardless of a client’s age or level of financial capacity—and even long before dementia has been diagnosed.

Document Goals And Values To Spot Concerning Financial Behavior

It’s important to document the values and goals clients communicate to you. Of course, many advisory firms do this upfront as a part of the financial planning process anyway.

However, it’s normal for a client’s priorities to change over time, so it’s also important to periodically and systematically revisit them as part of your normal ongoing service process with clients. That way, if your client’s spending changes and no longer aligns with their values and goals as you understand them, you can document it, and quickly address it. This may be simply a clarifying conversation with your client. Or, it could be a red flag indicating a decline in financial capacity.

You should also consider ensuring through your processes that you are in contact with your senior clients frequently and consistently. While there is no industry standard, a phone call or in-person conversation at least once a year can be used as a general rule of thumb. If there are any concerns about diminishing capacity, the frequency might be increased to at least twice a year.

Document Important Personal Relationships For Trusted Contacts

At our advisory firm, we request copies of POA documents from all clients to keep on file, along with current contact information for the agents named in their Powers of Attorney, so we can readily be in touch with them if needed.

Similarly, you could ask your clients to provide you with designated trusted points of contact (for the advisory firm to contact directly if necessary), and custodial TCPs as well.

Ideally, have a form for this purpose (to request trusted contacts), that your client can complete and sign. Corgenius, a company that offers grief support education and resources to advisors and consultants, provides some helpful suggestions for how to document this. I often describe this as an ‘In Case of Emergency’ form, and it should be clear about when you can use the emergency contacts your client provides to you, to demonstrate that you understand how sensitive financial conversations with others can be.

You can also ask your client to introduce you to their advocates directly, while all is well. That way, if something goes wrong, you have already established a personal connection. (Of course, you may also find that being introduced to important people in your client’s life could lead to more valuable business relationships for your practice, too!)

Documenting Investment Plans Is About More Than Just Investment Management

It’s generally a good idea to document your clients’ investment plans in a formal Investment Policy Statement (IPS) for general business purposes. But it’s particularly helpful for protecting you and your client if they contact you with an urgent or unusual request that significantly deviates from their IPS.

If you are concerned by a request, you might ask your client to put the request in writing or sign a new IPS. This is not only good practice for your business, but can be a cursory screen for a client with dementia, since they will often have trouble writing. If the client is unable to comply, you and your Chief Compliance Officer can then decide whether it’s time to discuss your concern with your client or contact a third party—whether that is your client’s established advocate, the custodian, regulator, or Adult Protective Services. Though generally, I recommend, where reasonably possible, that you not contact a third party until you have a conversation about your concern directly with your client first.

Estate Planning Around Diminishing Financial Capacity

Good estate planning provides important protection if someone becomes unable to manage their finances – it’s not just about planning for death, but also for incapacitation. Thus, it is important to have a POA, as discussed above, so someone can step in and make financial decisions as your client’s advocate if needed.

Additionally, a revocable living trust can be a very good planning tool for diminished capacity. A trust can be set up to make it relatively easy for a successor trustee to step in and take care of managing assets titled to the trust, such as brokerage accounts, bank accounts, and real estate (in a more expedited manner than activating a Power of Attorney, which can be especially challenging when it’s a Springing Power of Attorney and requires a doctor’s certification to become active). Personally, we found having a Revocable Living Trust to be very helpful when assisting my grandmother. It is common for most clients to name the same person as their POA and successor trustee.

If a POA or revocable living trust is not available for the client, a less preferable (and more expensive and time-consuming) alternative is to ask a probate court to name someone to act as guardian and/or conservator. While a bank account or brokerage account can be titled to a trust, you cannot do the same for retirement accounts such as IRAs, 401(k)s, etc. A successor trustee who becomes acting trustee can usually restrict your client’s access if needed (i.e., to prevent withdrawals or trading). But a custodian may not restrict your client’s access to place trades or request withdrawals from an IRA without a court order, even if a POA has authority over the account.

Practically speaking, I have found, in most cases, the combination of a POA and revocable trust provide great protection for clients and allow families to avoid having to name a guardian or conservator.

Establish Employee Training On Spotting Diminishing Capacity

As mentioned earlier, the Senior Safe Act only provides immunity if the advisor can document that they and their appropriate team members have received training on the following:

- How to identify and report suspected exploitation

- Protecting client privacy and integrity

As such, it’s recommended you add 10-15 minutes to your annual compliance training to include this essential piece. There are advisor resources such as those provided by Advisor Assist that can provide the training, and the session does not need to be a day-long seminar – a few highlights go a long way to help employees be much more aware of what to look for, and how to address a concern if it does arise.

Protecting senior clients can also be added to annual compliance conversations as a routine topic of discussion, which potentially has the added benefit of making compliance meetings more relatable to the advisor’s daily work with clients (and thus a more engaging meeting!).

Manage The Red Flags Of Potential Diminishing Capacity

When a client makes a withdrawal request, they often mention what the money is for: a big trip, home repair, or other expenses that align with their goals and values.

A key component of financial capacity is the ability to understand why you are doing something, and its potential consequences. If your client makes a significant withdrawal request out of the blue, without explanation, you might wonder if it is appropriate to ask what it is for. The answer is yes, it is appropriate. Because the client’s response can actually be one of the biggest red flags of emerging diminished capacity.

In our later section on holding client conversations, we’ll explore how to inquire politely, without seeming too nosey when we cover how to communicate during a crisis.

Manage Immediate Crises When Discovering Diminished Capacity Or Financial Exploitation

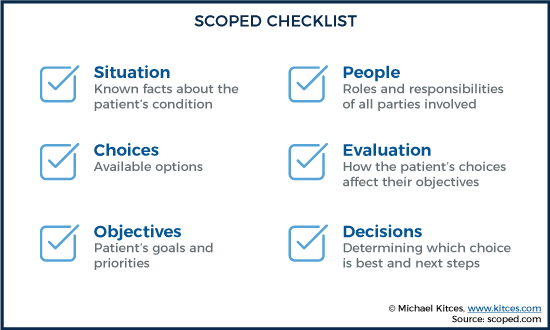

Beyond managing the long-term relationship, diminished capacity typically generates additional ongoing ‘brush fires’ to be tamped out. Even in emergency situations, it can be very valuable to remember that a structured process can make our job easier and improve outcomes.

Medical practitioners use the SCOPED decision-making checklist to facilitate sensible decision-making in uncertain and crisis situations, which can readily apply to our practice as well.

Not surprisingly, the SCOPED checklist aligns with the fiduciary processes envisioned by Fi360 and the CFP Board, both of which incorporate at least four broad steps: (1) gather information; (2) formalize recommendations; (3) implement; and (4) monitor progress and repeat.

During a crisis, your firm’s Chief Compliance Officer should ultimately decide if it is appropriate to contact the advisor’s trusted contact. When that happens, it is appropriate to share information about the situation at hand with the trusted contact, but not go further than that (e.g., it is probably not appropriate to share information about a client’s full financial picture).

It may also be appropriate to notify the custodian as well, who hopefully will have their own trusted contact person (TCP) on file. The good and the bad of raising a concern with the custodian is, once notified, they will control what happens with the account going forward, and their policies and procedures may override the advisor’s own wishes in how to handle a delicate client situation. In my experience, the custodian will likely err on the side of being overly restrictive. Which is unfortunate, as it may discourage cooperation between advisors and custodians, where cooperation could be very valuable for all parties involved. But custodians won’t get better at addressing senior needs unless we bring issues to their attention.

(Editor’s Note: For further discussion on applying a fiduciary process for clients with dementia, see this Journal of Financial Planning article co-written by Steve Starnes and Thomas West, entitled, “A Fiduciary Approach for Clients Who Need Long-Term Services and Supports”.)

Putting The Pieces Together: Managing The Stages Of Cognitive Decline

The moment you suspect your client is becoming mentally impaired, it is time to get someone else involved (whom ideally you have already identified, and received previous written permission to reach out to as a trusted contact), such as a friend or family member who can serve as your client’s advocate.

Initially, this person may join meetings simply to listen. If your client develops dementia, at some point the advocate will need to take primary responsibility for managing the client’s finances. I discuss additional recommendations and some behaviors that may be observed through each of the stages of dementia in the December 2010 Journal of Financial Planning article mentioned earlier.

Your client’s financial advocate may also be the primary caregiver. It is important to understand the substantial cost of caregiving, in terms of time, energy, and stress. It is common for the caregiver to feel overwhelmed, which may inhibit judgement and decision-making. The recent article I co-wrote with Tom West, “Advising Clients Under Stress”, addresses this topic in much more detail.

Responsible Relationships And Delicate Conversations That Help Guide Decision-Making

With all the conversation here about naming advocates, POAs, and trusted contacts, an important aspect should not be forgotten: whenever possible, you should always try to talk with your client about your concern before contacting others. Trusted contacts are an option in case of emergency, but you don’t clamber down the fire escape if it is easier to walk safely out the front door.

That being said, conversations about diminished capacity are never as fun for anyone as, say, planning to take the entire family on a Hawaiian holiday. In fact, you should unfortunately expect that communicating with your client will become increasingly difficult as their dementia progresses.

Consider this situation, for example:

John, an 85-year-old client, calls me. He just received his brokerage account statement, and is upset and confused. “I’m not doing too well! I want to sell what I have left!” he tells me.

Sympathetically and calmly I ask, “John, why are you angry?” He accuses me of losing all his money and asks how he will pay his upcoming tax bill. I feel bad for John. I can only imagine how awful it must be for an 85-year-old to believe he is almost broke. Actually, John is misreading his account statement. I know this because I have had this conversation with him before. How can I help him?

Your job will be much easier if you utilize a few important listening and communication tools to help your client feel understood. To facilitate conversations, Whealthcare Planning provides very useful tools to help advisors engage with clients about financial caretaking, identifying the risk of financial exploitation, and planning around aging. We have used these tools with clients, and are impressed.

Remember that working with clients with dementia can be time-consuming and frustrating, and it also can increase your professional liability. Dementia creates confusion, and a confused client is often an unhappy client who may share their dissatisfaction with their friends and family … without you being there to defend yourself. So it’s very important to always keep the communication channels with your client and their advocates as clear and open as possible.

Straightforward Engagement With Clients Regarding Diminishing Capacity

A client with dementia probably recognizes, and is frustrated by, their memory lapses and communication challenges. Offer empathy and reassurance; let them know you enjoy taking the time to listen.

Here are a few other tips:

- Let your client tell their own story in their own words. Though it may be tempting, don’t complete their sentences when they have trouble finding the right words.

- Before speaking, make sure you have your client’s attention, then speak calmly, clearly, and as simply as possible—without talking down to them.

- Avoid open-ended questions such as: “What would you like to drink?” Instead ask “yes” or “no” questions, or ones with simple direct answers, such as: “Would you like tea or coffee?” (This is especially hard for financial advisors. We are trained to ask open-ended questions such as, “What are your goals?”, “What is important about money to you?”, etc., but the language must change when it comes to situations of diminishing capacity.)

- Avoid potentially unclear pronouns, “him,” “her,” and “it.” Instead, use specific names for people and places.

- If your client does not understand, first try repeating yourself using the exact same words. If repetition isn’t working, you may use humor to relax the mood, perhaps joking about your own inability to remember details. If your client continues to struggle, try changing the subject and returning to the thought later, with different words.

- If your client remembers something imprecisely, be judicious about correcting them. Factual or not, it’s their reality, so a correction may serve no purpose. Worse, they may resent it. For example, if they think they last met with you a month ago when it was actually last week, it may be best to let it slide. But if they remember asking you to sell when they actually asked you to buy, this might be worth a correction, speaking calmly and using reassuring body language.

- To reinforce and aid memory, provide clients with a brief written summary of meetings and conversations shortly after they conclude, and include in the write-up the main bullet points of what was discussed.

- Utilize active listening skills to understand how your client is feeling. Habit #5 of Stephen Covey’s “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People” (Seek First to Understand, Then to Be Understood)is a good resource.

Including The Client’s Financial Advocate In The Conversation

An inability to understand or remember details also highlights the importance to encourage your client to bring a friend or family member to meetings. When your client remembers something incorrectly, their advocate can support what was actually discussed. Your client is also likely to ask their advocate first when trying to recall past conversations. This can be more efficient and effective for all concerned.

That being said, your client may resist adding a friend or family member to their meetings. How we handle money is often perceived as saying a lot about what kind of people we are. Clients may resist letting children or other family members help them with finances, because it leaves them feeling judged, vulnerable, or dependent.

Money is deeply personal. Here are some tips for helping clients feel comfortable with bringing a trusted individual to their financial planning meetings:

- Remind your client that they have made good financial decisions in the past; asking for help when needed is another one of those good decisions.

- Compare the experience to a doctor’s visit. Many people ask a friend or family member to accompany them to the doctor to help remember everything the doctor says. Similarly, even very healthy clients can benefit by having a trusted individual accompany them, to listen in on an advisor’s financial advice.

- When your client brings an advocate to the meeting, it’s especially important to focus on and include your client in the conversation. Also, when appropriate, reassure your client that their advocate is doing a good job. This will help your client feel more comfortable and help you build goodwill with the advocate.

- Supporting the client’s sense of independence and honoring their preferences will help both you and the advocate build trust, so the client will be more likely to accept help when needed.

To help the advocate monitor all of your client’s financial accounts, you might encourage them to be officially set up with Power of Attorney at the custodian and bank. Access to an account aggregation tool can also help the advocate monitor account activity, especially in the very early stages of decline. Fidelity recommends EverSafe, an online tool that monitors financial transactions and delivers alerts to named contacts if suspicious activity is detected. Alternatively, some advisory firms simply monitor client cash flows through their financial planning software’s account aggregation tools(e.g., eMoney Advisor).

The more you can help your client simplify and organize their financial picture, the easier it will be for you, your client, and your client’s advocate.

Communicating With Your Client’s Advocate And Expanding Your Professional Support Network

You and your client’s advocate should make every effort to support the client’s sense of independence and honor their preferences. (Even as the reality is that their independence may decrease with diminishing capacity, accentuating their loss of independence may only amplify the client’s fears.)

To do so, try to establish a shared, clear understanding of the client’s values and preferences regarding care and finances. Although the advocate may disagree with aspects of the client’s day-to-day financial choices, you both must focus on the client’s desires. The advocate should help navigate care needs, and concentrate on the big decisions aimed at safeguarding the client’s financial security.

Families managing Long-Term Services and Support (LTSS) need help with medical, legal, financial, emotional, and practical issues. No one professional can address all these separate, yet interconnected, areas of expertise. Advisors should consider expanding their networks to include referral sources for care managers, primary care physicians, home care providers, and bill-paying services. This extensive network will save time and enable planners to help clients make more-informed financial decisions and receive better care.

A professional care manager can help clients determine what assistance they need and then help them find a provider. Both the Aging Life Care Association and the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging (which provide directories of local resources) can help clients find a professional care manager.

Communicating During A Diminishing Capacity Crisis

What about those scenarios when a client calls or emails out of the blue with a request that doesn’t seem quite right? You certainly don’t want to deter a competent client from spending their money as they please; it’s not your job to judge their tastes. That said, it is your job to do all you can to prevent an incompetent client from hurting themselves. How do you proceed, especially if they’re unclear or tightlipped about their plans?

Perhaps you can casually ask, “Are you making a major purchase?” or “It is always good to hear from you! Are there any major updates in your life?”

Perhaps your client wants “$10,000 RIGHT AWAY” to send to their grandchild who is supposedly in trouble. It is normal for a grandparent to want to be supportive and helpful, but this scenario is a very common ruse scammers use to trick loving family members out of their hard-earned wealth. You might ask: “Have you talked with your grandchild’s parent to confirm where they are?”

Perhaps the client wants to make a major charitable gift and you’re not familiar with the charity. You could say: “I’m not familiar with that charity. Tell me more about that.”

Through conversation, you may identify that your client fully understands what they are doing. Again, it doesn’t matter if you agree with their spending priorities. But if your client can’t seem to explain what they are doing, or it seems dramatically out of character, it can be a red flag suggesting they are being taken advantage of, or are experiencing cognitive impairment. If so, you can then consider using some of the controls now in place thanks to the Senior Safe Act and similar advances to delay the disbursement from occurring, as we covered earlier… and then begin the process of engaging the client’s trusted contact person to get their entire support network more involved.

An Advisor’s Privilege And Duty In Managing Diminished Capacity

There may be few greater privileges than being entrusted to safeguard someone’s financial well-being according to their most heartfelt values and highest goals. It’s no wonder our highest satisfaction as advisors comes when we are able to build enduring client relationships that last a lifetime. And how fortunate are your clients and their loved ones, to have your experience, advice, and guidance to lean on throughout their lives?

It’s startling when we realize a vibrant, valued client is suffering from cognitive decline. Not only might we be among the first to observe its milder symptoms, we may also be aware of them even before our clients themselves have recognized them, or internalized that it may only be a matter of time before they will no longer be able to manage their own financial decision-making.

During this period when your client is most vulnerable, you may be one of the few protections standing between them and financial exploitation by another. You’re also essential to prevent them from self-inflicting irreparable harm to their own financial security. Thus, our same privileged position is also our greatest responsibility.

I hope I’ve provided a number of inspirational ideas, practical strategies, and informational resources for positioning yourself, your staff, and your practice to better manage the threat of diminished capacity.

I suggest preparing for this particular threat in the same way you prepare for any other threat to your clients’ financial success: by understanding the regulatory, business, and relationship-building logistics involved in protecting and guiding clients with diminished capacity. By doing so, you are not stepping outside of your role as their lifelong trusted advisor. Quite the contrary: You are fulfilling your highest purpose.