Executive Summary

After several years of speculation and more than a year since the President issued an Executive Order on “Strengthening Retirement Security in America”, the IRS has released its proposal to update the life expectancy tables used to calculate the annual Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from all sorts of tax-preferenced accounts, including IRAs and 401(k)s, for both lifetime account owners and their (stretch) beneficiaries. Most notably, this is the first time the tables have been updated since 2002, despite the fact that life expectancy has increased more than 2% (or 1.6 years) for all Americans, and more than 8% for Americans who have reached the age of 65!

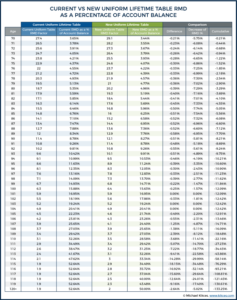

Central to the proposal (which must still go through the formal approval process and thus might not “go live” until sometime next year, though the proposed changes wouldn’t take effect until 2021 anyway) are updates to the RMD factors used to calculate required minimum distributions themselves in each of the three different life expectancy tables, including the Uniform Lifetime Table (for retirement account owners to calculate their RMDs during their lives), the Joint Life And Last Survivor Expectancy Table (used by account owners who have named a spousal beneficiary who is more than 10 years younger), and the Single Life Expectancy Table (which is used by beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts to calculate their so-called “stretch” distributions).

However, while lowering RMDs across the board will result in some increased tax deferral benefits, the changes likely won’t have as much of an impact for retirement account owners and beneficiaries as was likely hoped for. Specifically, according to data provided by the IRS, of the Americans who are required to take distributions from retirement accounts, only roughly 20% are taking no more than the minimum required. Which means that the remaining 80% are taking more than the required minimum, thus making any decreases in RMDs a moot point.

The question then becomes, will lowering RMDs for those 20% (who likely already have enough wealth to meet their retirement needs in the first place) have a material impact on their account balances as they age? For account owners and beneficiaries who have been extremely fortunate with their returns over the years and have much-larger-than-typical account balances, perhaps. However, when considering someone with an IRA valued at $1 million, the first year RMD would only decrease by roughly $2,100, and only a portion of that amount would have been due as taxes; the value of deferring that tax liability is only the growth potential on those taxes… which are hardly amounts that could significantly alter someone’s overall financial picture later in life (especially for already-affluent retirees), even when considering that the RMD factors continue to increase through the years.

And that lack of impact stretches even to those who have much longer life expectancies, such as younger individuals who have inherited a retirement account and use the Single Life Expectancy Table. A 40-year-old, for example, would see only a tenth of a percentage point decrease in the required distribution amount in the first year, which won’t be a very material difference, even for those who rely on that extra income from an inherited retirement account.

Notably, though, individuals taking RMDs will need to consider the transition to the new life expectancy tables if/when they take effect in 2021. Which, for lifetime RMDs for existing retirement account owners, is fairly straightforward – to simply use the new table in 2021 – though those who defer their first age 70 ½ RMD from 2020 into 2021 must still use the ‘old’ tables for the 2020 RMD. In the case of beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts looking to stretch, the transition process is a bit more confusing, as such beneficiaries cannot simply use the new life expectancy tables going forward at their current age. Instead, they must retroactively determine what their ‘original’ stretch period would have been in the past under the new tables, and then adjust forward to where that distribution schedule would be today (by subtracting 1 for each subsequent year since the year after the original account owner’s death).

Ultimately, the key point is that, while updates to the life expectancy tables have been a long time coming (especially since other tables – like those used by the IRS to analyze life insurance contracts – have already been updated to reflect longer lifespans years ago), the proposed changes simply won’t make much of a difference for the vast majority of retirement account holders and beneficiaries. Still, for those who take ‘only’ the minimum required by the IRS, the decreases might not provide that much of a benefit, but at least it does help to defer some taxes, which is hardly ever bad news.

Editor's note: On November 12, 2020, the Federal Register released a Final Regulation providing guidance on the life expectancy and Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) factors needed to calculate RMDs from qualified retirement accounts. The updated factors will apply to distribution calendar years beginning on January 1, 2022, and not on January 1, 2021 (as originally proposed).

On November 7, 2019, the IRS released its much anticipated Proposed Regulations to update the life expectancy and distribution period tables that both owners of retirement accounts (e.g., IRA, 401(k), 403(b) and the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP)), as well as their beneficiaries, use to calculate Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs).

Notably, it has been nearly two decades since the current set of life expectancy tables were released by the IRS as part of the Final Regulations for RMDs issued in April 2002 (that put in place the current RMD rules used today). Since that time, actual life expectancies have continued to increase, but since those increases have not been taken into account by the IRS, retirement account owners and beneficiaries have continued to be ‘forced’ to distribute funds from their accounts as quickly as was the case for retirees of the same age in 2002, even though retirees today are living longer lives!

Consider, for instance, that although life expectancy has actually declined slightly in recent years, it’s still meaningfully longer than it was in 2002. For example, someone born in 2002 had an estimated life expectancy of 77.0 years, while in 2017 (the most recent year, at the time of this writing, for which data from the CDC is available) the estimated life expectancy of a newborn child had reached 78.6 years, which represents more than a 2% increase in life expectancy.

And perhaps of even greater importance with respect to the RMD retirees are subject to for their own accounts, life expectancies of those reaching more advanced ages showed similar increases. For example, while in 2002, the average 65-year-old was estimated to have an average life expectancy of 17.9 years, by 2017 that life expectancy had grown to 19.4 years.

In response to these increases, the IRS has received a number of requests to consider revising and updating its life expectancy tables, which are used to calculate RMDs from retirement accounts. The most significant - and from a policy perspective, meaningful - of these requests came from President Donald Trump in an August 31, 2018 Executive Order.

Among other requests, including several related to Multiple Employer Plans (MEPs), the Order, which was created with the purpose of “Strengthening Retirement Security in America”, included instructions to the Secretary of the Treasury (the IRS) to consider updating the current set of life expectancy tables.

More specifically, Section 2(d) of the Order stated:

Updating Life Expectancy and Distribution Period Tables for Purposes of Required Minimum Distribution Rules. Within 180 days of the date of this order, the Secretary of the Treasury shall, consistent with applicable law and the policy set forth in section 1 of this order, examine the life expectancy and distribution period tables in the regulations on required minimum distributions from retirement plans (67 Fed. Reg. 18988) and determine whether they should be updated to reflect current mortality data and whether such updates should be made annually or on another periodic basis.

Now, roughly 15 months after the issuance of the Executive Order, the IRS has concluded its review, and has proposed new life expectancy tables that reflect today’s longer life expectancies. Per the preamble of the Proposed Regulations:

In accordance with Executive Order 13847, the Department of the Treasury (Treasury Department) and the IRS have examined the life expectancy and distribution period tables in §1.401(a)(9)-9, and have reviewed currently available mortality data. As a result of this review, the Treasury Department and the IRS have determined that those tables should be updated to reflect current life expectancies. [Emphasis added]

Notably, though, the updated tables are part of what are, at least for now, just Proposed Regulations. Thus, they must still go through the formal process, including a public comment period, before they are finalized and can used by retirement account owners and beneficiaries.

That said, given the fact that the changes proposed by the IRS are relatively straightforward and non-controversial, it’s likely the changes to the tables will be finalized sometime in 2020 in the same or substantially similar form. This would allow the tables to begin to be used to calculate RMDs for 2021 and beyond, which aligns with the effective date contemplated by the Proposed Regulations, themselves.

Proposed Regulations Update Life Expectancies For All Three Tables

While an individual can only have one true life expectancy – after all, you only live once! – when it comes to the tax laws and retirement accounts, an individual may be ‘given’ several different life expectancies simultaneously by the IRS from which RMDs are calculated, depending on the nature of the retirement account in question (e.g., their own retirement account versus an inherited account), and in some cases, the beneficiary of that account!

To that end, both the Final Regulations published in April 2002, as well as the Proposed Regulations issued by the IRS on November 7, 2019, incorporate the use of three different life expectancy tables, each of which is applicable in different situations. They are as follows:

- The Uniform Lifetime Table;

- The Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Table; and

- The Single Life Expectancy Table.

Each of these tables, in their currently used forms, can be found in Appendix B of Publication 590-B, Distributions from Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs).

The Uniform Lifetime Table For Lifetime RMD Calculations

The Uniform Lifetime Table is the life expectancy table that is most familiar to IRA and other retirement account owners. That’s because it’s the table that is generally used to determine the life expectancy factor for calculating RMDs during an account owner’s lifetime.

Specifically, the table is used by all retirement account owners, other than those who have named a much (11+ years) younger spouse as their sole beneficiary for the entire year, to calculate the RMDs applicable to their own retirement accounts (but not inherited retirement accounts).

The table begins at age 70 (though only 70-year-old individuals born between January 1st and June 30th use the age-70 factor), which is the youngest age for which an RMD can apply to one’s own retirement account, and provides a decreasing life expectancy factor (which produces an RMD that is a higher percentage of the previous year-end’s account value) for each subsequent year until a person reaches age 115 (at which point the factor levels off to 1.9)!

The Joint Life And Last Survivor Expectancy Table For Much-Younger Spouse RMDs

The Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Table is also used by (some) retirement account owners to determine lifetime RMDs for their own accounts (as opposed to post-death RMDs from inherited IRAs). However, comparatively few retirement account owners actually qualify to use the table because, in order to do so, an owner must name a spouse who is at least 11 years their junior as their sole beneficiary for the entire year. Since most spouses are closer than a decade apart in age, few individuals are eligible to use the Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Table.

For those who are eligible to use this table, the table will yield a higher life expectancy factor, and thus result in a lower RMD calculation, as compared to the result that would be achieved if the Uniform Lifetime Table were used by the same owner.

The Single Life Expectancy Table For Beneficiaries Of Inherited Retirement Accounts

The Single Life Expectancy Table is the third and final table used to calculate RMDs for retirement accounts. Unlike both the Uniform Lifetime and the Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Tables, however, the Single Lifetime Table is never used by retirement account owners to calculate required minimum distributions during their own lifetime. Rather, it is used only by (all) beneficiaries to calculate the RMDs from their inherited retirement accounts when the life expectancy method (the “stretch”) of calculating distributions is used.

How The IRS-Proposed Regulation Impacts Required Minimum Distributions For IRA (And Other Retirement Account) Owners

As noted earlier, the Proposed Regulation issued by the IRS on November 7, 2019 revise the three aforementioned life expectancy tables to account for today’s relatively longer life expectancies (compared to the current set of life expectancy tables published in 2002). These longer life expectancies result in higher life expectancy factors, which in turn would lower required minimum distributions and ultimately preserve more tax-deferred dollars over the lifetime of the account owner. That’s the good news.

The less exciting news is that, in the aggregate, the changes are likely to have a minimal impact for most retirement account owners.

Consider, for instance, that the updated life expectancy tables only change the absolute minimum that is required to be distributed from a retirement account each year. Owners are always welcome to take more than the minimum. And many (in fact, most) actually do.

Lowering The Amount Of The Required Minimum Distribution Only Helps Those Who Can Afford To Take Less Than The Current Required Amount

To that point, according to data provided by the IRS in the Proposed Regulations, “roughly 4.6 million individuals, or 20.5% of all individuals required to take RMDs from an affected retirement plan, will make withdrawals at the minimum required level in 2021”. Though data from other sources, such as the Investment Company Institute’s research paper “The Role of IRAs in US Households’ Saving for Retirement, 2018” (in which some 93% (!) of households headed by an individual 70 or older claimed to calculate distributions from their IRA based on the required minimum amount), would seem to call this data into question. However, if the IRS-provided information really is accurate, that would mean nearly 80% of retirement account owners would receive practically no benefit from the proposed changes.

After all, if you’re already taking more than the current required minimum distribution, you’re doing so voluntarily, ostensibly because you need to use the additional amounts distributed to meet living or other expenses. Therefore, it would only seem reasonable to assume that those same distributions (amounts already in excess of today’s higher RMD amount) would need to continue in the future, to support the same expenses.

Thus, lowering future RMD amounts may potentially only benefit about 20% of all retirement account owners who, according to the IRS, appear to have enough wealth and/or other income to be able to take only the new, lower proposed minimum distributions amounts going forward. Though to be fair, it’s likely that this group is disproportionately represented in advisors’ client bases, as such high-income/high-net-worth individuals tend to be served by the advisor community in greater percentages than all taxpayers as a whole.

Evaluating The One-Year Impact Of The Proposed Changes To Lifetime Required Minimum Distributions

So then, what about those individuals who can afford to take only the minimum amount in a quest to preserve maximum tax deferral and minimize taxable income? Will the IRS’s proposed changes to the Uniform Lifetime Table (and to a lesser extent, the Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Table) create a tax-savings bonanza? Not likely.

Because while the proposed updates to the Uniform Lifetime Table do provide some relief from RMDs, that relief is rather nominal, especially when looked at on a year-by-year basis. For example, a single individual who turned 70 ½ on November 7, 2019 calculates their first required minimum distribution (for 2019) by dividing their 2018 year-end account balance by 27.4. That equates to a required minimum distribution of approximately 3.65% of the prior-year-end balance.

By contrast, under the proposed changes to the Uniform Lifetime Table, the same individual would calculate their first required minimum distribution by dividing their 2018 year-end balance by 29.1. Thus, they’d have to distribute roughly 3.44% of their prior-year-end balance. That’s a difference of just over two-tenths of one percent (or looked at differently, the RMD amount using the new table would be 5.75% less than the current amount).

How would that look in terms of tax-savings when translated to dollars? Obviously, it depends on the size of the account, but the first-year impact on an IRA as large as even $1 million would be fairly inconsequential.

Consider that, at the current 3.65% (approximate) first-year-RMD rate for the individual noted above, the RMD on a $1 million IRA would be $36,500. Meanwhile, the same RMD, calculated using the new Uniform Lifetime Table amount of roughly 3.44% would be $34,400. That’s a difference of just $2,100.

Thus, if an individual were within the 24% Federal tax bracket, the result would be a one-year reduction in Federal income taxes of ‘just’ $504 ($2,100 x 24%). Even for a person subject to the highest current tax rate of 37%, the annual tax savings would amount to only $777. And growing that by a conservative growth rate of 6%/year amounts to a tax-deferral value of just $47/year of additional growth thanks to the reduced RMD.

The difference between the current RMD amount and the proposed future amount rises somewhat as clients enter their mid-80s, but is still not likely to be the RMD panacea many high-income individuals are hoping for. For example, the annual difference between the current RMD amount and the proposed future RMD amount peaks at 84, before dropping back to being equal by the time the owner is 101 (before the difference spikes dramatically higher after owners reach age 105, a relatively advanced age that, even with today’s longer life expectancies, few individuals ever reach).

At age 84, the life expectancy factor pulled from the Uniform Lifetime Table is 15.5, which equates to a required minimum distribution of approximately 6.46% of the prior-year-end balance. Using the factor from the proposed new Uniform Lifetime Table, the same 84-year-old individual would calculate their required minimum distribution by dividing their 2018 year-end balance by 16.8. Thus, they’d have to distribute roughly 5.96% of their prior-year-end balance. That difference of a half of a percentage point yields an age-84 RMD amount that would be 7.74% lower than the current amount required to be distributed by an individual of the same age.

Again, however, we have to consider the potential impact this change has on an individual’s big picture, and the answer is likely to be “not much”. Using the same $1 million IRA prior-year-end valuation as before, an 84-year-old using the current Uniform Lifetime Table would have a lifetime expectancy factor of 15.5 and calculate an RMD of $64,600. The same individual, using the proposed new table, would have a lifetime expectancy factor of 16.8 and an RMD of $59,600, which is $5,000 lower than the current amount.

If such an individual were within the 24% Federal tax bracket, the result would be a one-year reduction in Federal income taxes of $5,000 x 24% = $1,200, on which the subsequent growth on the tax-deferred dollars would be just $72/year. Meanwhile, the tax savings for someone in the highest Federal tax bracket would be $5,000 x 37% = $1,850, which amounts to $111/year of economic tax deferral value (for a $1,000,000 IRA!).

And while neither of these amounts is a trivial amount of money for many individuals, similar amounts of tax-savings often go unnoticed by individuals of more modest means (as evidenced by the disappointment of many individuals when they filed their 2018 returns and realized they had been given similar amounts back throughout the year via reductions in withholdings that were never fully understood).

(Note: Similar impacts would be felt by those retirement account owners using the proposed new Joint Life and Last Survivor Life Expectancy Table to calculate lifetime RMDs.)

Evaluating The Cumulative Impact Of The Proposed Changes To Lifetime Required Minimum Distributions

But what about the cumulative impact of these changes over a retirement account owner’s lifetime? Surely, there has to be a sizable impact of these updates when looked at in totality, right?

Perhaps surprisingly, not really. At least not in many instances. Consider the following:

Example 1: Clarice is a wealthy retiree who turned 70 ½ years old on November 7, 2019. At the end of 2018, her IRA balance was $1 million. She does not need any of the money in her IRA and plans only to take the required minimum distribution amount each year, reinvesting the after-tax amount of her distribution in a taxable account.

Clarice is in the 22% Federal income tax bracket, and like clockwork, she earns a 6% gross rate of return annually for both her IRA and her taxable account investments.

By using the current RMD life expectancy factors in the IRS Current Uniform Table table (see link to PDF chart, above), we can calculate the RMDs that Clarice takes from her account each year. If Clarice were to take only the RMD amount from her account each year, she would have roughly $821,000 (after factoring in her 6% annual return rate) in her IRA by age 95.

Furthermore, if we assume a blended tax rate of 18% (owing to a combination of ordinary income tax rates and long-term capital gains rates) on the annual gain in Clarice’s taxable account, at age 95 she would have roughly $1,382,000.

Now, let’s suppose that the new Proposed Regulations have been approved, and that from day one Clarice calculates her RMDs using the new proposed Uniform Lifetime Table. By calculating her account balances with these new RMD factors, Clarice will have roughly $916,000 in her IRA, and about $1,364,000 in her taxable account by the time she reaches age 95.

Thus, the end result is that using the new, proposed RMD values, Clarice would have about $95,000 more in her yet-to-be-taxed IRA, with about $18,000 less in her taxable account. In the end, Clarice’s true, after-tax-net-worth has grown by around $77,000.

Transition Rules For Retirement Account Owners

The transition from the current life expectancy tables to the new life expectancy tables should be fairly straightforward for most retirement owners. Simply put, beginning with required minimum distributions calculated for the year 2021 and beyond, retirement account owners would pull their factor from the life expectancy tables in the newly Proposed Regulations.

While the befuddlement of retirement account owners should be kept to a minimum, the greatest source of confusion may be for those retirement account owners turning 70 ½ next year, in 2020, but who wait until (as late as April 1,) 2021 to take their first distribution. Notably, while such individuals may, in fact, wait until (as late as April 1,) 2021 to take that first RMD, that RMD is for 2020. Thus, it would be calculated using the existing life expectancy tables effective in 2020, and not the new life expectancy tables effective in 2021 (even if that 2020 first RMD is taken in 2021!).

Example 2: Jamie is turning 70 ½ on August 5, 2020. He is still working but plans to retire in October of 2020. Given the income Jamie will earn during the first 10 months of 2020, he does not want to take any additional income from his IRA. As such, he plans to take both his 2020 and 2021 RMDs from his retirement account in 2021.

On February 8, 2021, prior to his April 1, 2021 required beginning date, Jamie calls his financial institution to process his 2020 RMD. That amount should be calculated using the December 2019 year-end balance, and the current, ‘old’ Uniform Lifetime Table factor for a 70-year-old of 27.4.

Shortly thereafter, on February 15, 2021, Jamie calls his financial institution to process his 2021 RMD. Under the Proposed Regulations (which would presumably have been finalized by then), Jamie’s RMD will be calculated using the ‘new’ Uniform Lifetime Table factor of 28.2.

How The IRS-Proposed Regulations Impact The “Stretch” For IRA (And Other Retirement Account) Beneficiaries

Unlike IRA and other retirement account owners, there is no uniform starting age at which a beneficiary of an inherited retirement account must begin taking distributions based on their life expectancy. Rather, unless the 5-year rule applies, distributions to beneficiaries must begin by December 31st of the year following the year of death, based on whatever age they happen to be at the time those distributions begin. Thus, the age at which a beneficiary must begin taking distributions is determined primarily by the age they are at the time that they inherit (as opposed to those taking lifetime RMDs, which ‘always’ begin at age 70 ½ [unless the still-working exception applies])!

For instance, a beneficiary who turns 34 years old in the year that they inherited an IRA must begin taking RMDs based on their life expectancy – as determined using the Single Life Expectancy Table – in the (subsequent after-death) year that they turn 35! Similarly, a beneficiary who turned 65 years old in the year that they inherit a retirement account must begin taking RMDs based on their life expectancy in the year that they turn 66. As a result of this variable RMD start date for beneficiaries, relative to age, there is no way to analyze the “standard” impact to beneficiaries.

Nevertheless, like the changes made to the Uniform Life Expectancy Table, the changes made to the Single Life Expectancy Table are unlikely to have a material impact to most beneficiaries. Like most IRA owners, for instance, many beneficiaries take more than just the minimum required amount each year. In fact, a significant number of beneficiaries cash out their inherited accounts virtually right away, despite the potential tax impact. The Proposed Regulations’ changes to the Single Life Expectancy Table are of no use to such persons.

Similarly, even for those beneficiaries who do stretch, the proposed changes are not likely to create much of an impact. For example, a beneficiary who inherited an IRA in the year that they turn 39 would need to begin taking RMDs, based on their Single Life Expectancy, from their inherited IRA beginning in the year that they turn 40 years old.

Under the existing Single Life Expectancy Table, the life expectancy factor for a 40-year-old is 43.6. By contrast, the factor for a 40-year-old using the Single Life Expectancy Table in the Proposed Regulations is 45.7. Thus, instead of the first RMD calling for a distribution of roughly 2.29% of the prior-year-end balance under the current rules, the new factor would reduce that amount to approximately 2.19%. This ‘whopping’ tenth of a percentage point difference in the amount required to be distributed is unlikely to be a huge boon to many… if any.

On the other hand, it is fair to argue that the new table will give a 40-year-old beneficiary an additional two years of tax-deferral for their inherited funds, as the life expectancy factor is, indeed, just over two years longer. Those two years, however, add ‘life’ to the inherited retirement account at the back-end of the stretch. For a beneficiary beginning to take distributions from their inherited IRA at 40 years old, the ‘bonus’ two years of tax deferral offered by the Proposed Regulations’ changes to the Single Life Expectancy Table would apply only after 43 years of RMDs from the inherited IRA had already been distributed, as the final age when the final RMDs must occur is pushed out from age 81 to age 83 instead. Thus the impact of this extension is significantly muted.

Understanding The Transition Rules For Beneficiaries Of Retirement Accounts

Unfortunately for beneficiaries, the manner in which RMDs from inherited retirement accounts are calculated, coupled with the way in which the IRS has proposed implementing the new Single Life Expectancy Table outlined in the Proposed Regulations, makes the potential transition for beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts more difficult for those beneficiaries than it does for retirement account owners for their own lifetime RMDs. Because it requires more data… and more math!

Notably, other than the prior-year-end balance, the only thing that an IRA (or other retirement account) owner needs to know in order to calculate their lifetime RMD for the year is their age. With this information, the owner simply looks at the Uniform Lifetime Table and selects the life expectancy factor next to the age they will turn on their birthday for that year.

By contrast, the general rule for beneficiaries (which applies to all beneficiaries, other than a limited exception for certain spousal beneficiaries who remain a beneficiary of an inherited retirement account [as opposed to, say, doing a spousal rollover of the amounts into a retirement account in their own name]), is that they only look at the Single Life Expectancy Table to find the appropriate life expectancy factor one time… in the year after they inherit an account.

At that point, their life expectancy factor is locked in and it is no longer appropriate to look at the Single Life Expectancy Table in future years to calculate the RMD (as doing so will, over time, result in a less-than-adequate required amount being calculated). Instead, the RMD factor to be used in future years is determined by subtracting one for each subsequent year in which an RMD must be taken.

Example 3: Jack turned 46 years old in 2019 and had inherited an IRA from his mother seven years ago, when he was 39. As such, he began taking RMDs from the account in 2013, the year following his inheritance, when he turned 40 years old.

Using the Single Life Expectancy Table, Jack determined that his first-year factor to calculate RMDs from the inherited account was 43.6. Since then, Jack has (correctly) avoided using the Table to determine his new factor, and instead, has subtracted one from the previous year’s factor to determine the factor for the current year.

For instance, when Jack was 41 years old, his factor was 43.6 – 1 = 42.6. Similarly, when Jack was 42, his factor was 43.6 – 2 = 41.6 .

Thus, for 2019, Jack’s life expectancy factor is 43.6 – 6 = 37.6.

The significance of this dynamic – where inherited retirement account beneficiaries simply subtract 1 from the RMD life expectancy factor, and don’t recalculate – is that it’s not clear how new life expectancy tables would be applied going forward when the life expectancy factors aren’t revisited after the initial year anyway.

To accommodate this, the Proposed Regulations contemplate replacing the current RMD factor (and future factors) for a beneficiary of an inherited retirement account as if the proposed new Single Life Expectancy Table had been in effect since the beneficiary inherited the account in the first place.

“Under this transition rule, the initial life expectancy used to determine the distribution period is reset by using the new Single Life Table for the age of the relevant individual in the calendar year for which life expectancy was set under §1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A 5(c)”

Thus, if finalized in their current form, the regulations would not simply allow a beneficiary to use their current age and pull their new life expectancy factor from the proposed new Single Life Expectancy Table. Rather, they would have to back into the current RMD amount by pretending that they had been using the revised table all along, calculating what their original RMD stretch period would have been in the first place under the new table, and then subtracting 1 per year from that RMD factor to advance back to the current and future years going forward.

Example 4: Recall Jack, who turned 46 years old in 2019 and inherited an IRA from his mother when he was 39. Further recall that he began taking RMDs at age 40, using a factor of 43.6, and has since calculated his new factor for each year by subtraction one from the previous year’s factor.

As a result, absent any changes to the life expectancy table, Jack will have a factor of 43.6 – 8 = 35.6 in 2021, when he turns 48 years old.

However, if the Proposed Regulation are finalized, Jack’s 2021 factor would be reduced. But not as much as he might think! Notably, the factor for a 48-year-old using the Single Life Expectancy Table in the Proposed Regulations is 38. But this is NOT the correct factor for Jack.

Rather, he must use the proposed new table to determine how his original factor needs to be adjusted for the year when he began taking distributions and, as before, subtract one for each subsequent year.

The Single Life Expectancy factor for a 40-year-old under the Proposed Regulations is 45.7. Thus, Jack’s actual RMD for 2021 (assuming the regulations are finalized) when he turns 48, will require him to use a factor of 45.7 – 8 = 37.7.

While this is not dramatically different from the factor of 38 an uninformed beneficiary in Jack’s position might use, it’s important to remember that any RMD shortfall would be subject to a rather onerous 50% penalty.

For some time now, it has been expected that the IRS would revise its roughly 20-year-old life expectancy tables that have been used to calculated required minimum distributions. After all, in the interim, other critical tables, such as those used by the IRS when analyzing life insurance contracts, have been updated to reflect mortality improvements. Thankfully, the IRS has now proposed to do the same for retirement account owners and beneficiaries.

Unfortunately, the proposed changes are likely to be a ‘big nothing’ for most individuals, whether they are retirement account owners themselves, or the beneficiaries of inherited accounts.

The fact that these changes have actually been proposed, however, is big news. Thus, there’s a decent chance that clients will be asking about the impact the proposed changes may have on their own personal situations, and advisors should be prepared to answer those questions.

The bottom line is that the proposed changes aren’t going to result in any dramatic differences, but for those only taking distributions from their retirement accounts because the IRS says they have to (and not because they need to rely on the distributions for living expenses), there will be a slight reduction in the required minimum distribution amount, ultimately preserving more of the owner’s tax-deferred dollars. Even though the relative level of resulting tax-savings may be small, though, arguably any relief is still good news.

When are they going to get around to up dating the taxation of Social Security.

If the SECURE Act ever passes and mandatory RMDs start at 72 instead of 70 1/2, then the initial RMD at 72 under these new tables will be roughly the same as the current RMD at age 70 1/2.

I’m 74, and have taken RMDs as required. I know I don’t need to take RMDs for 2020. When I am back at in in 2021, can I use the newer, slightly more favorable Uniform Lifetime table?

Is there any update to this? I’m looking and have not seen any changes to the IRS tables as of September 2020. I understand they may be thinking about other things this year, but have you heard any discussion on this?

The updated table was finally approved, but doesn’t go into effect until 2022. https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/blog/irs-finalizes-updated-tables-for-calculating-required-minimum-distributions/

Good article. Thanks. Is the Biden administration/Democrats still considering confiscation of IRAs and replacing with a gov’t SS payment like the 2008 Argentina gov’t did?