Executive Summary

Over the past several years, despite numerous programs from a wide range of organizations encouraging women, people of color, and minority groups to join the profession, the financial planning industry has struggled to increase diversity among its ranks. Which appears at least in part to be due to the fact that, while a 2019 CFP Professionals Survey showed strong job satisfaction among women, Black, and Latino CFP professionals, those satisfaction levels are still materially lower than for ‘traditional’ white male CFP professionals, signaling that the financial planning profession may be attracting more diversity but is also losing diverse CFP professionals at a faster rate… such that the overall diversity among CFP professionals has not increased despite a steady rise in both the total number of certificants and the number of diversity programs targeting them. Because the reality is that the problem is not necessarily one that can be addressed by increasing diversity efforts alone, and instead appears to be that increasing inclusion efforts is the key to increasing (and maintaining!) a more diverse pool of financial planners.

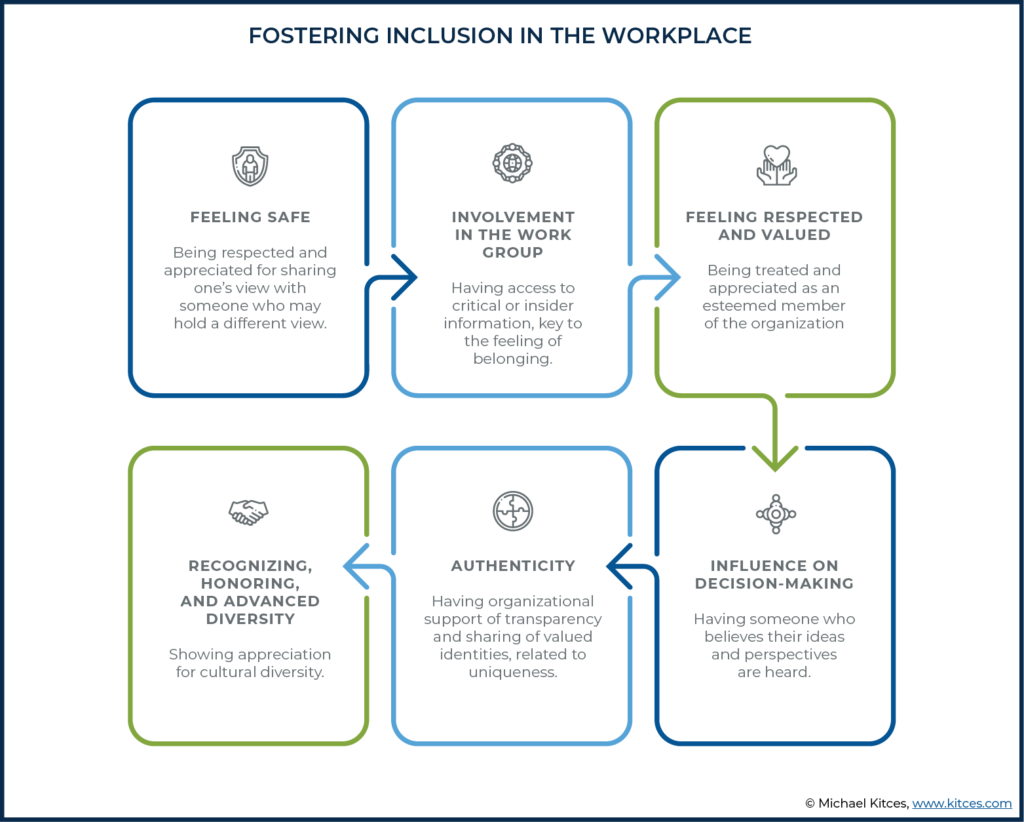

Whereas diversity efforts can be thought of as sending invitations to (more) guests to attend a party, inclusion efforts are separate from those of diversity and can be thought of as asking the guests who arrive to actually dance and engage with other guests. Inclusion involves helping individuals feel safe, involved in the group, respected, and valued. It also recognizes and honors cultural diversity, supporting individuals to express themselves authentically and as valued members of the organization. Furthermore, researchers have found that without efforts to facilitate inclusion, diversity policies can actually be damaging to an organization by upsetting the racial majority, who can tend to feel that the diversity programs are set up to unfairly discriminate against them.

Importantly, effective diversity and inclusion training programs are dynamic and necessarily take into account the unique potential prejudicial viewpoints of their participants, which can range from blatant (openly expressing prejudicial opinions) to symbolic (veiled but deliberately expressed) to aversive (subconsciously expressed). Depending on the participants involved and their respective viewpoints, good training programs can simply encourage individual self-reflection, or can incorporate philanthropic community engagement to give participants opportunities to interact with individuals from more and different cultural backgrounds.

Financial advisory firms looking for ways to increase diversity and inclusion can start by developing mentorship programs to support new financial planners of all backgrounds and by investing in scholarship programs to help aspiring CFPs meet their education and exam requirements. Even compensation can be structured to be more supportive of diversity and inclusion efforts, adopting different compensation models such as monthly or hourly subscription fees to help newer advisors who may initially lack the social structures to thrive on commission-based or AUM-based compensation models (that have disproportionately relied on new financial planners coming from backgrounds and ZIP codes that already have significant financial affluence to turn ‘friends and family’ into initial clients).

Ultimately, diversity and inclusion are important aspects of the financial planning industry that can only help businesses succeed. Not only does a diverse industry workforce better serve a diverse client base, it also helps firms retain diverse employee pools and gives them access to a richer pipeline when recruiting new talent. Despite the shortfall of diversity efforts in our industry so far, a growing focus on inclusion – particularly including mentoring, and organizing/attending conferences and events dedicated to supporting specific groups – can help the industry work towards achieving a net increase in diversity, and not simply bringing in more diverse financial planners only to continue to lose them a few years later.

It's time to really talk about the financial planning industry’s ongoing efforts of diversity… and what has still ended out being a sustained lack of diversity in the financial planning profession, which at least in part appears to be a result of the shortfalls of only focusing on diversity without its key counterpart, inclusion. And these issues matter because, not only is diversity increasingly being shown to be good for business, but also because of a more important universal truth – that at the heart of each and every one of us, there is a need to feel included and a desire to express our authentic selves without fear.

The financial planning industry desperately wants to increase the numbers of women, people of color, and minority groups within its ranks. The financial planning industry is so serious about this that the CFP Board has even put out multiple reports arguing the business case for increasing the number of women CFP professionals and creating a more racially inclusive profession.

And these reports, at first glance anyway, reveal a relatively positive picture. For instance, 74% of women with a CFP designation indicated they were satisfied with their careers, and 68% of Black CFP professionals and 59% of Latino CFP professionals would recommend financial planning as a career. People are pretty happy. However, you are likely wondering, how does this compare to a broader collection of CFP professionals that predominately includes white males?

Which may help to explain the documented lack of diversity growth amongst CFP professionals. As the aforementioned 2019 report shows that even though CFP membership has grown from 73,684 in 2015 to 84,356 in 2019, the ratio of men to women remains dishearteningly stagnant. In 2019, as was the case in 2015, only 23% of CFPs were female, and the CFP Board has separately noted that the number has remained stubbornly flat at 23% for more than a decade now. And while a multi-year report on minorities and people of color has not yet been published, it is worth noting that in 2017 only 3.5% of CFP holders were Black or Latino (where the percentage of these groups across the US population is 13.3% and 17.8%, respectively).

So what point are we trying to make drawing attention to these two issues? Women, minorities, and persons of color make up very small numbers, and although not widely unhappy (according to the CFP Board reports) are certainly not as happy about their work when compared to a larger mostly-male and mostly-white sample of advisors. Which raises the concern that if they are not as happy, they will not stay... as research that has looked into this question from a global perspective does find that women (a similar study of persons of color and minorities was not found) do leave the profession at a higher rate than men (a gap that is hard to explain by ‘just’ reasons like childbirth, family change, or changing career goals). Which suggests that not only is there a lack of diversity, there is also likely a lack of inclusion.

In short, a metaphor I like to use to explain the difference between diversity and inclusion is that if diversity is being invited to the party (and we need to invite more people), then inclusion is being asked to dance while at the party (what can be done to get satisfaction and ultimately retention rates up for women and minorities). And the impact of inclusion over diversity is something individuals, firms, and the industry itself need to consider if the actual goal is not just to create a more diverse workforce but also to maintain a diverse workforce.

The Difference Between Diversity And Inclusion, And The Problem Of Covering

The difference between diversity and inclusion – between being invited to the party, versus asked to dance while at the party – is important, as while increasing diversity is often cited as a sought-after objective, and a growing number of financial services firms are implementing hiring approaches to attract a more diverse range of candidates and implementing internal diversity policies, it might actually be damaging to do so without fostering inclusion as well.

For instance, an article published in the Harvard Business Review in 2016 found that diversity training often had little positive impact and concluded that diversity programs can actually make companies less fair because of how they can serve as a scapegoat excuse for the majority.

Essentially, diversity policies that are implemented can run the risk of being used by leaders to discount or invalidate what a person of the minority may feel, as the fact that there was a training program to ‘deal with’ diversity issues causes actual diversity challenges in the workplace to be downplayed.

Example 1: Gemma is a Black female financial planner and often works closely with her boss, Sarah, a white female financial planner. Recently, Gemma and Sarah had a meeting to discuss a new client, and when Gemma made a comment about the client and her understanding of their situation, Sarah laughed and responded, “No way Gemma, and besides you only think that because you are Black.”

When Gemma responded that she found Sarah’s comment hurtful, Sarah used the diversity policy against Gemma by saying, “Gemma, I am not racist, I respect Black people. I have even implemented a diversity policy here at the firm. You are just being oversensitive.”

Gemma endures another painful attack and realizes, diversity policy or not, her opinions are not welcomed.

Furthermore, a Harvard research study found that having a diversity policy alone (without policies to facilitate inclusion) also tended to upset the racial majority. In this study, researchers found that if diversity was highlighted, then members of the majority had a tendency to believe that they would be discriminated against.

Example 2: Tom, a white financial planner, works alongside Gemma. They were both hired around the same time and have been working as associate financial planners at Sarah’s firm.

Tom received the news today that Gemma would be moving into a senior financial planner role and, instead of being happy for her, Tom in fact believes that this was simply a ‘marketing’ move to support the firm’s diversity initiatives and rather than as a result of Gemma’s abilities.

Tom believes that the diversity policy is now effectively discriminating against him and may blame the diversity policy in lieu of considering the shortcomings in his own abilities relative to Gemma.

In summary, policies that focus on diversity alone are not always very effective, and it is important to recognize that inclusion, although often used interchangeably with diversity, is a separate key ingredient for diversity to be positive.

So to differentiate between these two constructs, let’s start with some basic definitions. To understand the differences between diversity and inclusion, it can be helpful to think about a room of individuals:

- A room where everyone is the same is not a diverse room.

- A room where each person is different is a diverse room, but not necessarily an inclusive room.

- An inclusive room that is diverse is one where the focus is not just on the fact that there are a lot of different people in the room, but also that the views and information from each person individually matter.

Furthermore, it is also worthwhile to point out that being inclusive is complex and has many facets – all of which help to achieve different goals and speak to the different needs of the individuals that may be involved:

- Feeling safe – being respected and appreciated for sharing one’s view with someone who may hold a different view;

- Involvement in the work group – having access to critical or insider information, key to the feeling of belonging;

- Feeling respected and valued – being treated and appreciated as an esteemed member of the organization;

- Influence on decision-making – having someone who believes their ideas and perspectives are heard;

- Authenticity – having organizational support of transparency and sharing of valued identities, related to uniqueness; and

- Recognizing, honoring, and advancing diversity – showing appreciation for cultural diversity.

Research has documented that, in practice, using and distinguishing between the concepts of diversity and inclusion is very common (and is not just a matter of semantics, or something that research academics think exists). For instance, a qualitative investigation found that employees defined diversity as having “many different people at the table.”

Inclusion, on the other hand, was when each of these different people felt safe, comfortable, and encouraged to share their opinions and ideas and have those ideas matter to other individuals at the table.

In our own industry, the CFP board has also distinguished between diversity and inclusion and provides the following definitions:

- Diversity: All the ways in which people differ, encompassing all the different characteristics that make one individual or group different from one another. It is all-inclusive and recognizes that everyone and every group should be valued. A broad definition includes not only race, ethnicity and gender – but also age, national origin, religion, disability, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, education, marital status, language, and physical appearance. It also involves different ideas, perspectives, and values.

- Inclusion: The act of creating involvement, environments, and empowerment in which any individual or group can be and feel welcomed, respected, supported, and valued to fully participate. An inclusive and welcoming climate with equal access to opportunities and resources embrace differences and offers respect in words and actions for all people.

The CFP Board also discusses broader forms of inclusion and says, within “inclusive organizations and societies, people of all identities and many styles can be fully themselves while also contributing to the larger collective, as valued and full members”.

Furthermore, this idea of inclusion has universal importance – we all want to feel included as individuals. Yet, from the research, even though we know what these ideas are and how they are supposed to feel, people are often still hiding their authentic selves.

‘Covering’ As A Defense Mechanism To Mask One’s Individual Authenticity

For instance, at the 2019 CFP Diversity Summit, speaker Kenji Yoshino presented research on what he has coined “covering”. Covering is when an individual feels that they cannot be themselves at work. In other words, employees might internalize their feelings, hide their natural communication style or even their visual identity (e.g., clothing, hair, etc.), thus showing up to work without a sense of their own identity at all. Instead, they may play to the accepted mainstream views of that office or industry, feeling unable to express themselves authentically.

And to this point, even the mainstream (i.e., white males) may not feel mainstream. Yoshino found that more than 45% of white males do not feel that they can be themselves at work either, and need to “cover” themselves in certain scenarios, such as to hide their religious or political affiliation, or that they came from a low-income background or have a mental illness.

Example 3a: Jenna is a female financial planner and is very career-focused, to the point that, in an effort to appear single-mindedly focused on her work to be recognized as a “hard-worker” by her boss, she does not put pictures of her kids up on her desk or in her office.

Example 3b: Darren is a Muslim and, instead of praying in his office, he escapes to his car to pray, to keep other office mates in the dark as most, as far as he knows, are Catholic.

Example 3c: Jeremy, a white male financial planner, uses his PTO instead of a sick day or simply asking for an afternoon off, to visit the doctor. Jeremey is struggling with depression and is ashamed to let anyone know he sees a therapist.

An important aspect of inclusivity is that it applies to everyone: women, minorities, people of color, people with (and without) religious beliefs, people that are gay, bi-sexual, transgendered, or straight, and non-minorities (even white males).

For many, the attempt to live up to an archetype – even for those who come closer to, at least on the exterior, resembling that archetype – is cause for a constant struggle to “cover”.

Achieving Inclusion Requires A Better Understanding Of What Prejudice Really Is (And Isn’t)

As many readers would likely agree, prejudice is a very loaded word in modern society. But it is also very misunderstood.

For example, while most people understand that prejudice, in general, is a preconceived evaluation of an individual based on what is stereotypical of others with the same characteristics (whether they are based on their identity, physical appearance, age, or beliefs), research actually identifies three forms of prejudice: blatant, symbolic (modern/color-blind), and aversive.

- Prejudice that is openly expressed, and that can be labeled as an outright “ism”.

- A client does not want to work with Lydia, simply because Lydia is a female financial planner, and the client believes that women are inherently not capable of being good at math and finance (i.e., sexism).

- Prejudice that may be implicitly but deliberately expressed, yet is veiled because an individual recognizes that it is no longer socially acceptable to be blatant and thus hides their “ism”.

- Frank, a fellow planner at the same firm where Lydia works, makes a joke at Lydia’s expense after hearing about what happened to her. When she asks him to stop, he simply says she is taking it too seriously because she is a female, and if she wants to stay in this industry she needs to lighten up.

- Daniel, a white planner, thinks the diversity/inclusion stuff is ridiculous. He worked hard to get where he is…if everyone else would just work hard they could get to where he is too. It isn’t his fault that women and minorities don’t know how to put in the work.

- Prejudice that may be subconsciously expressed by those who are unaware of their “isms”, and may even think or describe themselves as egalitarian or “not racist” (or insert other ism).

- John is a principal at a financial planning firm and, when faced with a recent hiring decision between two final candidates, Sarah and Tom, he chooses Tom even though Sarah was actually the standout. John has worked with very few women and, although he considers himself to be ‘pro-female’, he just does not feel comfortable hiring a female into this particular position.

In reality, almost everyone harbors some level of prejudices, and may not even be aware of it. Often, this is felt as anxiety or discomfort, and thus causes the person to shy away from taking any actual steps to confront their prejudicial feelings and to promote change.

How Diversity Training Programs Address The Prejudice Problem (Or Fall Short Of Doing So)

Depending on the type of prejudice (blatant, symbolic, aversive) and personal experiences (isolation, fear, support), different trainings, groups, and structures may be more or less useful for individuals and firms to bring about inclusion.

For instance, “unconscious bias training” is a very common type of prejudice training. The goal of this type of training is to help individuals to see or think of things from (and because of) their “privileged” vantage point, which they may not have thought of before. A famous example of unconscious bias training comes from Peggy McIntosh’s “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack”. And as the opening paragraphs describe, the reader is to read through or “unpack” many of the ways that being white holds privilege (some examples of the 50 ways included are a white person’s option to be able to avoid spending time with people they may have been trained to mistrust or who may have been trained to mistrust them; when shopping they don’t worry about being harassed or surveilled; they don’t consider it necessary to educate their children to be aware of systemic racism for their own daily physical protection; and they can do well in a challenging situation without their merits being considered a credit to their race).

This type of diversity training is direct and encourages individual self-reflection, and in some cases it can be a worthwhile exercise for those who want more awareness. However, many individuals struggle with this form of training, because they are not ready to be that self-reflective and/or to acknowledge that they indeed hold a prejudice. Furthermore, newer research actually finds that unconscious bias training isn’t as helpful as we once thought (as it tends to be more effective for those who were already inclined towards inclusivity, but may be an ineffective exercise for those who hold blatant or symbolic prejudices in the first place).

The advice here is not against unconscious bias training, but instead to perhaps make it available among other ideas and experiences. If someone is ready to commit to this type of self-reflection, great. If they are not ready, it can be available for them in the future.

Broader research on the impact of diversity training generally finds that diversity programs do not have much impact and may even just tell those who hold “ism” beliefs that they should not blatantly express those ideas but keep them hidden. In other words, diversity programs may simply turn blatant racism into symbolic racism, and in turn could even deepen resentment.

How Financial Advisors Can Increase Diversity And Inclusion At the Firm Level

So how can financial advisors support diversity and foster inclusion in their firms?

One option for diversity ‘training’ that actually works is simply to focus on diversity engagement. For example, Research on diversity programs that are effective tend to place importance on actually engaging and being in contact with individuals in different groups.

In a firm, this may mean just getting out into the world. For example, advisors can network at conferences that promote diversity or, if there is a philanthropic endeavor at the firm, the firm philanthropy could be used to engage with and interact with individuals from different backgrounds that do not normally tend to walk into your financial planning office.

Along that same vein, a firm leader or an industry leader may benefit from attending a diversity summit. The CFP Board puts on a Diversity Summit, which is geared toward actually learning about and understanding the issues of diversity and inclusion within the financial planning industry, and interacting with a more diverse range of industry participants (which otherwise tends not to happen naturally for most firms, given again that 77% of CFP professionals are male and more than 90% are white).

Another option, again leaning on broad research (as well as what CFP Board studies found), is to bring about inclusion through scholarships and mentorships.

For instance, CFP Board found as a part of its research on diversity and inclusion , there is a cost issue when it comes to obtaining the CFP designation. In the diversity and inclusion reports published by the CFP Board, getting the CFP marks can cost anywhere from $6 – 10k, and for the groups they studied (which often come from more socioeconomically-limited backgrounds), this represented a significant financial barrier. In my own research on students in financial planning programs, paying for the exam and for exam prep materials is a real concern, even after having completed the education requirement.

Yet before we decide that the perfect answer is to give money away to students so that they may attain their CFP, we also need to consider a counter (and I think very relevant) argument. Human capital and economic research would say that although we could ‘fix’ the issue by just having firms pay for the designations, this may not actually be the ‘best’ solution. And, in fact, given that in my experience in watching students “earning” the CFP certification really means something to the individuals that attain it, just handing out money is really not a perfect solution. Paying for and making it through the classes, studying for the exam, and actually passing the exam are all badges of honor to students.

Thus, the key is to implement a process through which someone can earn a scholarship (versus just giving them the money) to keep the human capital investment with the individual. This process could be designed to promote the individual’s career progress within the firm (think indirect revenue growth). For example, if an employee pays to take a class, they can be reimbursed for that class if they receive a certain passing grade. If it is about all upfront costs, the employer might also offer an education benefit. For example, at Kitces.com each employee has access to an education fund. I am able to spend my education money, which would not be enough to pay for the entire CFP program (which means I’d still have to put something into it myself), but would certainly cover a chunk of it. Other firms engage in a generous (but not 100%) payment arrangement, such as covering 80% or 90% of educational costs (but requiring someone to still have ‘skin in the game’ with the last 10% to 20%). Or there could be an internal scholarship that is earned over time, where the firm feels that the employee has given to the firm for this trade-off to be worth it for them as well.

Another important way to increase diversity and inclusion at the firm (and individual) level is to offer mentorship programs. When faced with stressful situations, we oftentimes hear that humans tend to “fight, flight, or freeze”, but in reality there is also ‘flock’. Coming together and supporting each other helps to counteract the other “f-word” reactions that might come to mind when making the types of changes that developing diversity and inclusion require of us.

Indeed, this is what the CFP Board research calls for, as well as what broader research also finds productive, in promoting diversity and inclusion. Essentially, mentorship programs are powerful tools because the protégé has someone fighting for them, teaching them the ‘ropes’, and ensuring that, perhaps, the protégé remembers to apply for that scholarship or take that class to help set them apart.

In a firm, this could be as simple as creating a hiring and mentoring program. For each new hire, a senior financial planner is involved in the hiring process and would ultimately be assigned to the new hire as a mentor. This mentor would then work with the new hire to show them the ropes, and to engage with the new hire to ensure that they understand and enjoy their work at the firm. The mentor may take time to practice presentations with the new financial planner and encourage them to seek out additional education opportunities.

Too nervous to rely on pairing new hires with a senior planner from day one? No problem. Once new hires starts, give them time to work at the firm and see if there is someone in particular to whom they naturally gravitate by setting up “getting-to-know-you meetings” and collaborative work experiences with a number of members of the firm. Then, after 2 or 3 months, have the new hires and other firm members each identify with whom they felt a genuine connection had been made and then start the more specific mentor-mentee relationship assignments based on the mutually defined ballots.

Other specific examples that have come out of the CFP Board’s research on how to increase diversity and inclusion that directly relate to our industry involve compensation.

For instance, minorities and women are often at a disadvantage in commission-based roles as they may not have the social structures (or otherwise come from ‘affluent Zip Codes’) to be able to “sell” right out of the gate. Thus, firms can make the decision to move away from commission structures and even possibly AUM, to business models that are more accommodative of a wider range of clientele in the first place, like hourly or monthly subscription fees. And the evidence of the impact of this change can be seen at XY Planning Network, who use a fee-for-service structure and have among their ranks a much larger percentage of minorities when compared to the industry at large (more than 15% non-white advisors at XYPN, compared to only 3.5% Black and Latino CFP certificants in the profession at large).

Another critical component that can be implemented at the firm level and, in many ways, is connected to the idea of mentorship, is a structured training program. Financial planning, as evidenced by the CFP Board’s studies, is an industry that people like once they get going – but it can be hard to get going. Moreover, having a structured training program helps new hires to move forward technically and skillfully, and also creates a time and place to talk about what a person may need for success at an individual level.

While there are certainly options for individuals of a majority to support diversity and inclusion, there are also support programs designed by and for minority groups (such as LGBTQ organizations, or programs designed to help Chinese students acclimate to US customs). Interestingly, there have been findings from studies suggesting that the impact of such minority programs may actually both help and hurt the minority’s role in the development of diverse and inclusive environments and experiences.

Consider the following. Research would support that attending a conference dedicated to a specific group has many benefits (such as finding support with others who may identify similar challenges). Returning to the idea of the other ‘f-word’, flock – flocking can be an incredibly healing and empowering activity. In a community environment shared with others, individuals can feel safe to share experiences and support one another. Research on college minority programs finds that these programs are very helpful for new students because they give the students a place to feel safe and supported, and to connect with each other.

As a woman, it can be helpful and restorative to have time to be with just other women.

There is evidence of this in financial planning, too. For example, participants at the 2018 CFP Diversity conference noted that being anything that isn’t the norm can feel isolating and horrible. Joining groups like AAAA or Women in Insurance & Financial Service National Conference is a great way to connect and feel supported as new planners ascend through their career paths.

Yet, even with all of these perks, this not a perfect solution. For example, despite the benefits of minority programs, it is still important to note that limiting oneself to engaging only in these programs prevents one from learning from different minority groups (or the majority)! For example, it would not be in support of diversity or inclusion if I were to tell all of my fellow female planners that we would be having our own meeting and that men would not be allowed, and could eventually becoming more limiting for one’s perspective! And that is exactly what the research found as well. Younger students benefited significantly from minority focused programs, but this became less of an impact with time.

Or stated more simply: programs for your group (whatever that group is), are great, and definitely worth doing. They offer safe spaces for connection and can be breeding grounds for mentorship opportunities. Yet, do not let this be the only thing that your firm does.

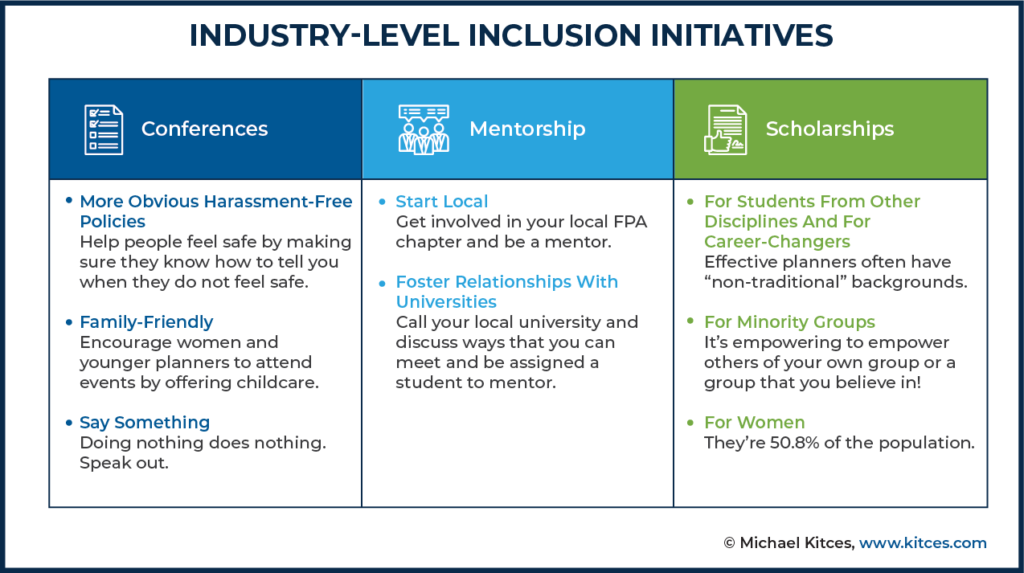

Inclusion Initiatives At The Industry Level Mirror Those At The Individual And Firm Level: Conferences, Mentorship, And Scholarships

Conferences are vitally important to the financial planning community. We use them to network. We use them to learn about new technology and discuss our ever-changing industry. And because inclusion is an important prerequisite for business creativity and innovative thinking, it is a key factor to a successful conference experience. Diversity alone cannot promote the same level of innovative thinking in the absence of inclusion.

Basically, when we feel individually validated and supported, we are more willing to share individual ideas. And with enough new and valued ideas being shared, creative and inventive things inevitably happen. Furthermore, as it turns out, burnout and stress also decrease. Said another way, not only does inclusion get the creative juices flowing, it also helps people to maintain the energy, drive, and excitement to take those ideas and do something with them! The importance of having inclusive conferences, then, is not something that can be underscored enough. (At least, once we’re past the pandemic and conferences are back again!)

As such, the following is a list of ideas that our industry leaders may consider when developing conferences:

- More Obvious Harassment-Free Policies. The problem with harassment is not just that it happens, but also the fact that it often goes undetected because many victims do not report it. And research shows they do not report it because they often do not know how. To address this, leaders can make reporting policies easy and explicitly clear. If you want to help people feel safe, be sure they know how to tell you when they do not feel safe, or worse, when something has happened. XYPN, FPA, Technology Tools for Today (T3), and eMoney have all implemented anti-harassment reporting policies.

- Family-Friendly If you want to encourage women and younger planners to attend events, make sure conferences offer a family friendly environment. This can be as simple as offering childcare at the conference, which, in fact, is a common and easy addition to add to many hotel contract.

- Say Something. As noted above, doing nothing does nothing. When things happen at conferences, like the now-infamous comments from Ken Fisher, speak up. Tell people it is not okay. Chip Roame’s open letter in response to Ken Fisher is a great example.

When it comes to mentorship, the financial planning industry simply does not have enough of it. Even though the CFP Board has done a nice job rolling out its mentorship program, there is still much more to be done. Especially when we see what the CFP Board has done, compared to other “mentorship” programs that have also been promoted, but may do less to support diversity and inclusion efforts, such as that developed by Edward Jones.

The Edward Jones program focused on trying to help women, people of color, and minorities to take over books of business. The program promised that any current advisor who gave away business to a woman or a minority would receive an additional 10% of their assets as an incentive.

The program incentivized working with women and minorities, but was done at the expense of purposefully leaving out white men, who, as we have discussed in this blog, may also struggle to fit the financial industry archetype. The end result was that the Edward Jones program may have sought to add to diversity, but it did so at the expense of inclusion.

Personally, I give Edward Jones the benefit of the doubt here and commend them for ‘doing something’ but, in retrospect, it is clear to see this as a great example of when diversity is promoted without inclusion. The Edward Jones program specifically excluded (and upset) white professionals, some of whom could also have come from disadvantaged or less connected backgrounds that needed similar support but were denied access to it.

Here are a few things to consider when it comes to developing strong mentorship programs for the industry at large.

- Start local. There are many, many FPA chapters. FPA has placed and continues to place an emphasis on mentorship. Get involved in your local chapter and be a mentor.

- Foster relationships between university programs and local practitioners. Students need mentors, but research finds that it can be difficult to find a mentor and ask for that relationship. If you are a practitioner, call your local university and discuss ways that you can meet and be assigned a student (or three!) to mentor.

As previously noted in the last section, scholarships are also key, and something that minorities, women, and people of color have made clear that they want. In fact, in the coming months Nerd’s Eye View will be compiling a list of financial planning scholarships, much like our master conference list, to be a resource for (future) financial practitioners. (If you want to suggest a scholarship we should be certain to include, please email [email protected]!) For the time being, those seeking CFP scholarships can also check out the CFP Board’s list of available scholarship programs.

Don’t yet have a scholarship, but want to create one (so you can join our list!) to contribute to diversity and inclusion in financial planning? No problem. Here is a list of ideas for why or how you might start your own scholarship. (Just don’t forget to email us once you are up and running!)

- Scholarships for students coming from other disciplines (because psychology students, if I do say so myself, make great planners!)

- Scholarships for job changers (because teachers and military are awesome at managing people!)

- Scholarships for minority groups (because it is empowering to empower others of your own group or a group that you believe in!)

- Scholarships for women (because we make up 50% of the population, and we are good with money, too!)

- Scholarships for the normal, everyday student (because it feels good to be supported and included no matter who you are!)

While some might ask, given the magnitude of the diversity shortfall in financial planning, whether the few changes suggested here enough? And my answer to that is no. The suggestions here are not enough, they are just a place to start. However, we will need diversity and inclusion to solve this issue.

Moreover, even though the ideas in this article won’t solve the issues today, they can serve as a springboard for new ideas that will ultimately address these important issues. Talking about these issues is hard, but the financial planning industry, given its firm-level flexibility, can be seen as a breeding ground for how to grow and become a diverse and inclusive industry in the most efficient and effective ways. We can actually be the industry that gets diversity and inclusion right – and that will be incredible for our members, our firms, and our clients.