Executive Summary

The approach of “save a percentage of your income” is a staple of retirement planning. While much debate exists about the exact ideal percentage, the concept is relatively straightforward – have savings to be one of the slices of your income pie, ideally automate the process with an ongoing percentage of your income that always gets saved first, and you’ll be well on your way to retirement.

Yet the reality is that saving something like 10% of your income also implicitly means you’re spending the other 90%, and continuing to do so over time means you'll also be saving (only) 10% and implicitly increasing your standard of living by 90% of ever raise you receive in the future. As a result, your standard of living rises as fast as your retirement savings, which means the amount needed to reach retirement gets larger and larger given the retirement costs to be supported, and in the end it’s surprisingly difficult to ever reach retirement at all as the goal forever outpaces the savings to reach it!

By contrast, an alternative approach is to try to spend “just” 50% of each pay raise you receive in the future (implicitly saving the other 50%). The end result of such an approach is that increases in the standard of living are more controlled and rise far more slowly, savings grow exponentially (to more than 20% of income within just a decade, even from a starting point of 0%!), and you can even retire early… all while feeling like your lifestyle is steadily rising as you’re still committed to spending more every year, just not increasing as rapidly as saving 10% of your income (and spending the rest)!

The Challenge With Saving 10% Of Income

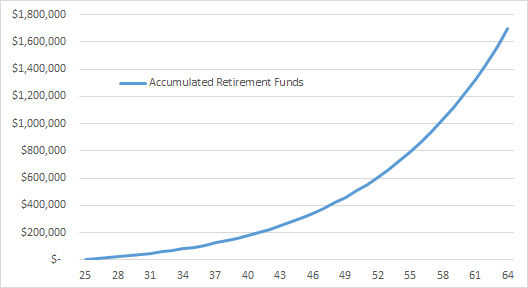

To understand the challenges of saving a percentage of income, let's assume “Jerry” is in his mid-20s and generating about $50,000/year in take-home pay. The chart below shows how much wealth Jerry will accumulate by saving 10%/year of his income. Assuming Jerry’s wages rise by 4%/year (including those raises he’ll get above cost-of-living adjustments as his career builds), and a long-term average annual growth rate of 7%, Jerry finishes with a healthy $1.7M after 40 years.

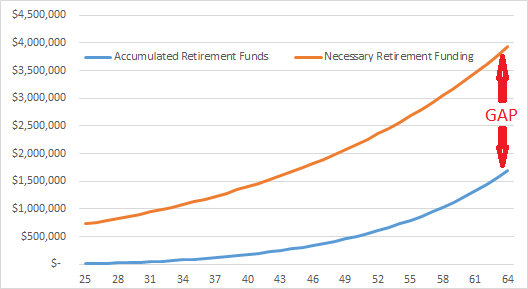

The caveat, however, is that by pursuing this path, Jerry’s actual cost of living will rise rather significantly along the way as well. After all, if he’s saving 10% of his income (and each raise along the way), he’ll also ramping up his lifestyle costs by 90% of each raise over time. Which means by the end at age 65, Jerry’s annual cost of living that started out at $45,000/year (the $50,000 take-home pay minus 10% savings) is now up over $200,000/year! Suddenly, that $1.7M of accumulations won’t go so far at all, when it has to support a $200,000/year lifestyle!

Of course, today’s future retirees will likely still enjoy some Social Security benefit as well. But even assuming an average Social Security benefit of $1,294/month (which would be a little over $50,000/year in 40 years at 3% inflation), Jerry still might need at least $150,000/year to support his future standard of living. With a 4% withdrawal rate, that means he would actually need about $3.75M (or 25X the spending goal) to fund retirement successfully. Which means by saving 10% of his income for 40 years, Jerry isn’t even half way there.

In fact, as the chart below illustrates, simply assuming a retirement goal of 25X inflation-adjusted spending after netting out a $1,294/month Social Security benefit, by saving 10% of his take-home pay (and adjusting his standard of living every year by the other 90% of your raises), Jerry never really makes much progress to retirement at all, as his standard of living and the necessary retirement funding ramps up as quickly as the savings itself, and a huge retirement gap remains at the end!

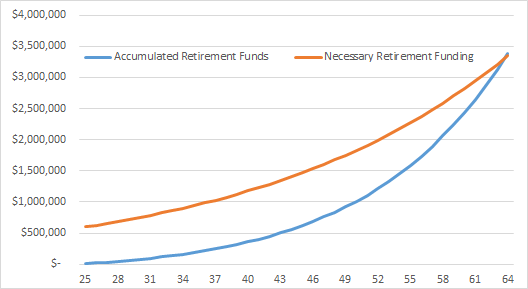

Ultimately, to make this approach work, it actually takes a whopping 20% annual savings rate to accumulate about $3.4M of wealth in 40 years, for Jerry to be able to fund the remaining 80%-of-take-home-pay standard of living in retirement (again, after netting out Social Security payments). Notably, the reason this works is not "just" because Jerry saves twice as much, but because he needs a bit less to retire when his standard of living is lower (because he was "only" spending 80% of his annual take-home pay).

Try Spending 50% Of Your Raises Instead

As a sheer accumulation approach, saving a percentage of your income (or take-home pay) every year is not a bad way to go, and leads to a steadily rising contribution to savings. The problem, however, as illustrated above, is that it also inherently directs the individual to spend the other 90% of his/her income as well, which increases the standard of living so much that there’s little progress ever made towards retirement goals. The funding needed for retirement grows as rapidly as the account balance does! By contrast, an alternative approach is to focus more significantly on spending instead, in an effort to control the rising standard of living.

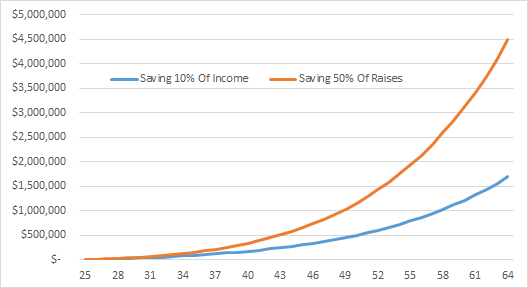

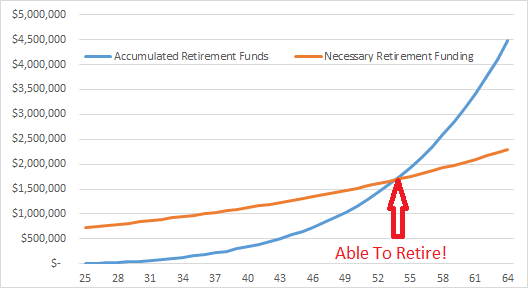

For instance, Jerry’s twin sister Sally doesn’t save 10% of her income; instead, she’s also already living on $45,000/year (and saving $5,000/year), and tries to bridge the gap by deliberating spending 50% (but only 50%) of each of her pay raises (earmarking the remainder of each pay raise to savings). The chart below shows how Sally’s retirement savings accumulate accordingly; after 30 years, she nearly triples the savings of Jerry's "10%-of-income" approach!

In addition, the reality is that by systematically NOT spending 50% of every raise, and thereby controlling her standard of living, the amount of money Sally needs to fund retirement never grows as much in the first place. After 40 years, by “only spending 50% of each raise” Sally has a standard of living that is 30% lower than Jerry’s, but without ever needing to give up current spending or having her lifestyle go backwards (it merely grew more slowly!)! In fact, the increased retirement savings, combined with the decreased need for retirement funds due to the less expensive standard of living, means Sally can actually retire 10 years early, by age 55!

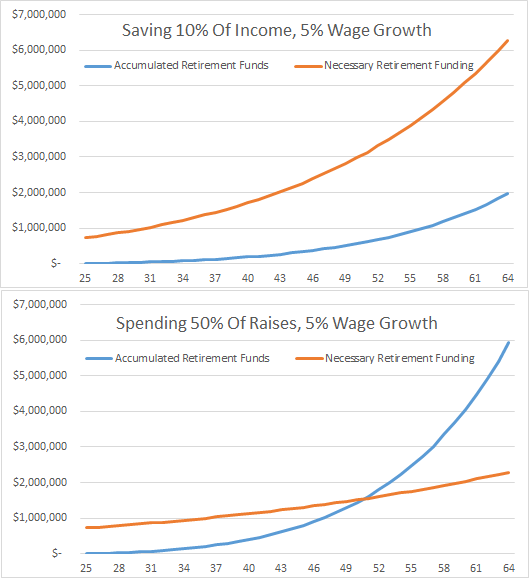

Notably, the effects are even more dramatic for those who have stronger careers that boost income more significantly than “just” 4%/year. For instance, if Jerry and Sally get wage growth of 5%/year, the charts below show the outcomes. Here, again, the importance of spending “just” 50% of each raise, and controlling the increase in the standard of living, is dramatic. Sally can now retire even earlier (around age 50), while Jerry is making absolutely no progress towards retirement because the greater income growth is just causing his standard of living to rise faster and his needs outpace his saving by even more!

Spending (A Portion Of) Raises And Behavioral Finance

One of the interesting “indirect” effects of the “spend 50% of your raise” philosophy is that it can achieve some astonishingly high savings rates. In the earlier chart, Sally starts at a 10% savings rate and begins to save 50% of every raise, and as a result ends out with a savings rate of more than 20% after less than a decade, and is saving more than 30% of income after 20 years. These high savings rates – along with the reducing spending that inevitably accompany them – are the primary reason Sally can retire a decade early, while Jerry still isn’t even half way to his retirement goal despite starting to save 10% of his income every year beginning in his mid-20s. Even if Sally has to slow his savings pace a bit later (as if her wage growth is low enough, her spend-50%-of-raises may eventually materially lag inflation), she's still so far ahead there's ample room for adjustments.

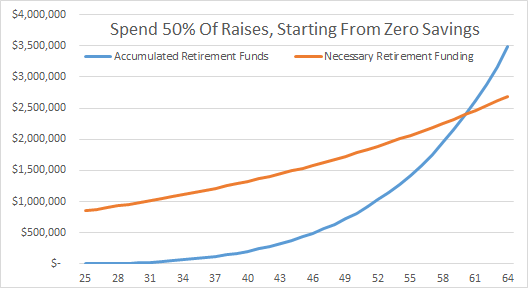

Notably, the “spend 50% of your raise” approach can also be an effective means of helping someone who isn’t saving at all right now, begin to do so. In essence, the approach is a form of Benartzi and Thaler’s “Save More Tomorrow” program, which takes advantage of our behavioral tendencies to help us to save – by recognizing that it’s much easier to commit to future saving than it is to try to save today. This can work not only because we tend to irrationally discount our future commitments – the reason we tend to put off saving because retirement is so distant is the same reason we’ll commit to future saving, because it too is so distant! – but the approach of “spend 50% of every raise” still fundamentally focuses on the part of income that we like: the spending! By giving ourselves “permission” to spend a large chunk of every raise, it suddenly feels a lot easier to save – since we know every raise will be accompanied by an enjoyable spending increase! – yet the results over the long run can be significant, as shown below for an individual who had no accumulated saving and a 0% current savings rate. After 10 years, the individual who might have said in the first place "I can't figure out how to save, there's just no money left to save!" is now saving almost 20% of income, without ever being required to give up any aspects of his/her current lifestyle, and will be on track to retire by age 60 without cutting current spending at all!

The focus on saving pay raises also shifts the focus to the importance of getting those pay raises in the first place. In fact, the impact of pay raises on the ability to save in the future is so powerful, young adults may actually be far better investing into their careers and training in their 20s than trying to start a tax-free Roth IRA in the first place. This is supported by some recent research suggesting that pay raises are not evenly distributed through our careers in the first place; instead, real pay increases may be as much as 2%-3%/year above inflation for the first 20 years or so, but then level off to being just even with inflation later. Which means it’s absolutely crucial to spend “just” 50% of pay raises in the early years, or the accumulator’s standard of living will ramp up so much in their 20s and 30s than they’ll never be able to bridge the gap by trying to save more in their 40s and 50s.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: an effective retirement saving strategy should consider not only how much of income to save, but also how those savings habits can impact spending habits as well. A strategy to save a percentage of income is also fundamentally a strategy to spend all the remainder of income, and every raise thereafter, which may actually be bad advice that puts retirement increasingly out of reach even as retirement savings accumulate. By contrast, a philosophy of focusing on spending your raises – but ”just” half of each raise – builds a path to increased spending, but in a much more controlled manner that makes it easier to save more and more income in the future, and makes the savings needed to retire a much less daunting goal in the first place! And for those who are struggling to save at all – or are saving less than they wish – an approach of spending “just” a portion of every raise can be a path to better savings habits in the future as well!

So what do you think? Could you implement a “save 50% of each raise” strategy with your clients (or even in your own lifestyle)? How do you help clients who are behind in saving and trying to catch up? How do you help clients to manage their spending so it doesn’t spiral upwards as their income rises?

I actually think that this is brilliant ! Looking at savings without looking at spending is all too common. People simply do not realize how intertwined savings rates and lifestyle inflation are. By attacking this issue on two (2) fronts– I think it comes across as a balanced and prudent strategy that should be the new rule of thumb.

Great article Michael.

A fascinating approach, but I do have one concern; aren’t we forgetting about inflation? If we are assuming a 4% increase in income and saving of half of it, that would leave only a 2% increase in spending. That might keep pace with inflation if inflation were to remain that low, but probably would not even then on an after tax basis. Thus Jerry would find himself with a standard of living as he approaches retirement that is no greater than he had in his mid 20s and probably lower once taxes are factored in. If he were to try to raise a family along the way, that might prove even more challenging.

People rarely consider inflation. Or, if they do, they believe the government’s bogus inflation figures. Food inflation in the U.S. is running 10-15% at present. And it is increasing every year. I hadn’t bought a “Whopper” in several years, and was absolutely shocked at what it now costs.

Pretty sure I’m a first-time commenter here. I’ve enjoyed following your blog for the last six months or so while learning about the CFP and working my way into the financial services industry.

I see this plan working well for those who on a well-defined career path, especially where salaries start relatively low and increase dramatically with education and experience (i.e. law and medicine).

However, in my own experience (and this likely rings true with many in the lower half of middle class Americans) it’s hard to define a raise because of one looming X factor that consumes 10% or more of annual incomes: health insurance.

For instance, let’s say you have someone earning $40K in a position at a large firm where health benefits cost $200 per month. That brings their salary to $37.6K after accounting for healthcare premiums.

Then they take a new job at a small company that bumps their salary to $45K, but healthcare premiums double *and* a child enters the picture. Their salary comes to $40.2K after healthcare, a modest increase of $2,600, but they also hit their family deductible of $3,000. Thus, if we’re counting salary after healthcare, we now have a decrease in pay from the previous job.

I understand we could just keep it simple by saving of the $5,000 salary increase. However, this means the client is expected to swallow higher premiums, a maxed-out deductible, and increased saving in a single year when they actually see a decrease in disposable income.

In short, my concern with following this model is the incremental increases in savings are so small that they’re likely to get lost among the much larger changes in salaries, benefits, family situations, etc.

I agree with the premise of this note. But I find it is easier to approach it from the opposite perspective. I tell younger folks to add a third of any raise to their automatic savings program (send it from your paycheck directly to their savings/investment account). You didn’t mention taxes but I assume you meant that they should only spend half of their after tax raise. My message is similar – 1/3 for savings, 1/3 for taxes, 1/3 for spending. Since raises come at the marginal rate plus payroll taxes, this is often a reasonable rule of thumb.

Good explication of consumption smoothing pioneered by the Samuelson/Kotlikoff school.

Great theory, and nice to see some “outside the box” thinking on saving– we certainly need it. Trouble I see with this, however, is the 10% initial rate will be fine when comp is around 50k but if comp grows by 4%/year it will soon grow to be high enough that, when multiplied by the higher savings rate that comes from saving 50% of raises, will exceed the legal limits (called 402(g) limits. For example, if 50k grew to 87,500 and savings grew to 20%, Jerry would hit the max 17,500 saving for the year…. great… but next year when comp was 91k, Jerry couldnt even save the 20% because of the IRS imposed limits. That would be a problem until age 50 when catch up would help a little… but not much.

Hitting the IRA contribution limits doesn’t mean you can’t save more in other accounts. I know Michael has done a post about using HSAs to increase your tax deferred savings, but obviously you can always use a regular taxable account to save as much as you’re willing.

To me, seeing how this might work in theory only reinforces the value of saving 20-30% of household income. If that means reducing one’s standard of living a bit, better to do it out of choice than to be forced into it later.

We had this issue and decided to simply save in a taxable account. Now, several years later, we have investments in tIRA, Roth IRA and taxable accounts. Its great because it gives us a lot of flexibility when we withdraw the funds later, and helps us control our future tax rates.

My standard guidance to folks is to focus on saving half of each raise and using the other half for OTO life experiences. You’ve done a wonderful job here of explaining just how effective the strategy is over the long time. As always great insights and great presentation Michael!

Great article and strategy. I’d like to see the analysis done on “Saving 1/2 your age as a percentage of income”. In other words at age 24, save 12%, at age 36 your savings rate is 18% of income, at age 50 you save 25%, etc. Seems to me it’s harder to save just getting started in career, marriage, housing, etc. and gradually gets ‘easier’ as you become more established and move-up through these life stages. And this strategy would give an increasing saving rate / lower growth lifestyle.

I don’t understand, why do I need less money to retire earlier in life? I will have more years to live with less savings, I know you are considering lifestyle changes but still not possible to retire at 25.