Executive Summary

Dave Ramsey has hosted the popular “Dave Ramsey Show” radio program since 1992 and founded Financial Peace University in 1994. Since then, he has helped millions of people with personal money management issues and has authored several best-selling books. Despite his popularity, though, many financial advisors have criticized the investment and debt management advice Ramsey frequently gives his listeners and readers. And while some of the advice that Dave Ramsey has given (e.g., assuming a 12% stock return, endorsing the debt snowball method of reducing overall debt, and encouraging 8% retirement distributions) may not result in optimal outcomes from a strictly technical perspective, the reality is that Ramsey’s advice has effectively helped millions of individuals and families reduce their debt, manage their money responsibly, and get on track to establish good financial habits.

For instance, while most advisors would agree that Dave Ramsey’s 12% return assumption for stock market investors is an alarmingly high return assumption, the reality is that using a high return assumption helps clarify the power of compound interest and the magnitude of potential wealth that can accumulate when new investors start saving early. In other words, the more compounding you see yourself missing out on, the more “FOMO” (Fear Of Missing Out) motivation it can inspire… which in practice, has been an effective motivator for many of Ramsey’s followers to start developing good savings habits!

Similarly, Ramsey’s advice to use the ‘debt snowball’ method – which advocates paying down one’s smallest debts first (in contrast to debts with the highest interest rates) as a means to tackle personal debt – is also under frequent attack. Yet while there’s no question that mathematically, paying off loans with the highest interest rates first is the most financially efficient method of debt reduction, borrowers who feel overwhelmed by debt are often more motivated to stick to a debt paydown plan when they experience the small psychological victories of eradicating their debt one at a time. Which means the most psychologically motivating approach really is to tackle the smallest debt first – actually pay it down successfully – changing one’s self-image to someone who can successfully tackle the rest of their (higher-interest) debt, too.

And many financial advisors, especially those who observe Bill Bengen’s 4% Safe Withdrawal Rate rule as the established norm, have also criticized Dave Ramsey’s 8% retirement distributions as dangerously high. However, while an 8% withdrawal rate is high, it is not necessarily as catastrophic as most advisors would suggest, given both the reality that many retirees can and do adjust their spending later if it becomes necessary… and that in practice, most retirees reduce their spending in the later years, anyway. Furthermore, higher withdrawal rates can be rational when we account for a retiree being willing to take some risk of running out of money, particularly when they have some guaranteed income, like Social Security, to provide a spending floor. And in practice, particularly for the audience that Ramsey is trying to reach, which may include individuals who got into debt trouble or started saving at a later point in life, a 4% withdrawal rate necessitates so much in retirement savings that it may simply feel unachievable for many – which, again, could de-motivate them from retiring (or saving) at all – while an 8% withdrawal rate target may feel like the goal is more achievable… which, again, helps them to actually follow through and take positive steps that improve their financial situation!

Ultimately, the key point is that even though Dave Ramsey may draw a lot of criticism from financial advisors who analyze his recommendations from a mathematical and technical perspective, he is very effective in helping a large number of people to change their financial behavior for the better, particularly those who need to get started on a substantively different path than the problematic one they are currently on (and may feel stuck on). His ability to help people modify their behavior may not rely on optimal advice from a technical standpoint but, notably, being ‘right’ isn’t necessarily always the most important factor for motivating and encouraging people to take the first major step of change in the first place. And so from a behavioral change perspective, there is quite a bit of ingenuity within Dave Ramsey’s advice (and the systems he has created to deliver that advice) that advisors may want to reflect on when helping their own clients change their behavior for the better!

Many financial advisors love to hate Dave Ramsey. While there are a number of reasons why advisors may not like him, one reason that gets a lot of attention is that his advice is often considered ‘wrong’. From his 12% return assumption to his debt snowball approach (of first targeting debts with the lowest balance, not necessarily those with the highest interest rate) and even to his 8% rule regarding retirement distributions (versus the more common 4% rule touted by advisors), Ramsey does give empirically minded critics a lot of ammunition.

However, if we look at Ramsey’s work and philosophy from a behavioral perspective, there is an underappreciated ingenuity to what he does, and perhaps some potential for advisors to reflect and take away a few insights for better serving our own clients.

Dave Ramsey’s Central Motivation – Helping People Make Better Financial Decisions

First and foremost, it is important to think about what Ramsey’s motivations are. While he is running a business (and there’s no shame in that!), he does seem to genuinely want to help his listeners and the broader community improve their financial lives.

Note the emphasis here. He is not trying to develop a personal finance encyclopedia, methodically and precisely cataloging all personal financial knowledge. He is not a researcher, seeking to uncover the truth of personal financial matters above all else. Both of those may be admirable pursuits, but they don’t describe what Ramsey is really doing. Rather, he is focused on helping people make better financial decisions and actually change their financial behaviors for the better.

In Herb Brooks’ speech (reenacted by Kurt Russell in Miracle) to the 1980 Men’s US Olympic Hockey team, he says, “You were born to be hockey players—every one of you, and you were meant to be here tonight.”

Is that a true statement? Probably not. It is not clear how we would even know if it was. But Brooks was obviously not saying it to portray literal truth. Instead, he was trying to motivate his players to carry out an action—namely, to play at their highest potential ability, by instilling in them a belief that their whole lives have been building up to that pinnacle moment of opportunity to perform at their very best.

If we look at some of Ramsey’s most despised advice through this intention-to-motivate lens, then it suddenly casts a different – and more favorable – light. Because the advice that Ramsey gives that is considered ‘wrong’ by many of his critics consistently nudges his audience (not necessarily all audiences, but at least the ones that he is trying to reach and help in the first place) in a good direction from a behavioral perspective, by helping them become more mindful about establishing beneficial money management habits. Which is important because if Ramsey was simply mistaken about certain financial matters, then we shouldn’t expect any level of consistency. Instead, we should expect his advice to be nudging people in good or bad directions more or less randomly.

In other words, Ramsey’s often-criticized advice isn’t just haphazard; instead, it consistently nudges his audience in a particular (and desired) behavioral direction.

Which is not to suggest that every piece of advice he’s ever given is flawless (even within the context of the overarching ‘method to the madness’). Nonetheless, when we look at much of his persistent advice – the advice that was not just uttered once but has become a significant component to Ramsey’s overall philosophy – that advisors love to hate, we do consistently see some strong behavioral benefits of how Ramsey frames certain issues.

Ramsey’s 12% Stock Returns Assumption

Let’s start off with one of Ramsey’s most hated claims among financial advisors: The assumption that you can earn 12% per year investing in the stock market.

Let’s set aside the technical criticisms of this claim (those have already been spelled out by many others) and instead think about this from the perspective of motivating client behavior.

Let’s assume that a 25-year-old who currently isn’t saving uses Ramsey’s Investment and Retirement Calculator to try and figure out how much they could have in the future if they started saving $500 per month. Plugging numbers into Ramsey’s calculator, the 25-year-old discovers that, at a 12% return, they would have about $5.9 million if they followed that savings pattern until retiring at age 65. By contrast, had they used an 8% return assumption, they would only have calculated about $1.7 million.

If the purpose of this exercise was to forecast how a portfolio with this savings pattern would grow over the next 40 years, then most advisors would probably like the lower assumption better than the higher one (if only to better manage expectations more conservatively, so the client isn’t unhappy by finishing with “just” $3M!?). But is that the point here?

The real goal here is to get someone to start saving. You want them to say, “I’m giving up that much?! Wow, I need to start saving today.” From that perspective, which return assumption would better facilitate that experience? I’m not sure how different the two actually are from a perception perspective (both may just sound like really big numbers to a lot of people), but $5.9 million is still bigger than $1.7 million and, as a result, is going to be more likely to generate a strong response.

Although not in reference to Ramsey or the assumptions he uses, Morgan Housel, in his new book The Psychology of Money, similarly references seeing an illustration of compounding interest as a potentially illuminating experience that allows people to realize how our intuitive tendencies to think linearly don’t apply to saving and investing:

I have heard many people say the first time they saw a compound interest table—or one of those stories about how much more you’d have for retirement if you began saving in your 20s versus your 30s—changed their life. But it probably didn’t. What it likely did was surprise them, because the results intuitively didn’t seem right. Linear thinking is so much more intuitive than exponential thinking. If I ask you to calculate 8+8+8+8+8+8+8+8+8 in your head, you can do it in a few seconds (it’s 72). If I ask you to calculate 8×8×8×8×8×8×8×8×8, your head will explode (it’s 134,217,728).

Again, the key point here is that the process of running a compound growth simulation is the experience of seeing how powerful compound interest is – not to teach people about the most precise capital market assumptions. And using a higher growth rate simply further enhances that experience, with the ultimate goal of getting someone to actually change their behavior.

In practice, it is also likely very hard for most consumers to track and assess their performance over time, particularly in light of the fact that savings rates and other assumptions will always continue to fluctuate. Which means, in the end, even if most investors will never actually achieve those 12% returns, many may not even realize what the actual returns compounded out to be. Either way, they’ll still likely finish with “sizable” retirement savings if they can at least start down that early savings path. (The exact behavior that Ramsey is trying to motivate.)

Of course, the risk with this type of motivational strategy is that someone could end up feeling frustrated by not seeing their assumptions manifest, causing them to give up. However, this risk is likely quite low in practice. Would we really expect someone to say, “This really isn’t working out how I thought it would. Yes, I paid down debt and started saving for retirement and have built up several hundred thousand dollars I never dreamed of having early on, but I thought I was going to get 12% returns, and I’ve only earned 9%, so I’m giving up on all of this and going back to my old ways.”

That seems doubtful. Rather, they set good behaviors in motion and are likely to simply adjust to whatever reality they encounter, not unlike how financial planners already help their own clients adjust when the future inevitably turns out at least somewhat different from the financial plans they originally created. Furthermore, by getting their financial house in order, this person is no longer in the core audience that Ramsey is speaking to. Perhaps they’ll look into the topic further and realize that the target date fund they are invested in with their employer is not 100% stock, and perhaps there’s a good reason why they shouldn’t always hold a 100% stock portfolio. Or maybe they will encounter one of the many arguments that explains why the return rate they’ve been using may not be a great assumption to use after all.

But, in any case, the key point is that the person who needed a little extra motivation to get started was actually the intended audience for the 12% return projection, and those who reach the point that they may be ready (and needing to) abandon Ramsey and his 12% return assumption have already built new positive savings behaviors (thanks at least in part to Ramsey’s advice that made them feel the costs of waiting were too high to not get started?).

Ramsey’s Debt Snowball Method

While perhaps less controversial than the 12% return assumption, Ramsey’s ‘debt snowball’ methodology is similarly not defensible on mathematical grounds but is defensible from a behavioral perspective, as the behavioral benefits have been more widely acknowledged.

What works particularly well about the debt snowball approach is that by successfully paying off one’s smallest debts first (which are not necessarily the ones with the highest interest rates) and racking up psychological wins, individuals can become more likely to stick with a strategy in the long run. Furthermore, these small wins can actually generate additional excitement or motivation that accelerates a debt repayment schedule beyond what was initially planned! Because in the end, paying off a daunting pile of debt can easily be demotivating – it can feel as though we’ll never pay it off – while paying off even one small debt can change one’s self-image to someone who can pay off their debt, building confidence to pay off even more debt.

In other words, advisors who get too hung up on the math of debt repayment optimization are missing the point. Yes, it is financially always going to make the most sense to pay off the highest interest debt one has first, simply because an equal number of dollars applied to the highest interest debt will result in the lowest total long-term debt payments. However, plans can change for the better with Ramsey’s advice (e.g., growing confidence to repay one’s debts faster, or at least stick with an aggressive repayment plan), while they may actually be at greater risk of a change for the worse with the traditional advisor advice (a daunting repayment plan that assumes perfect compliance and no change in motivation over time; traditional advice to pay off high-interest debt first, no matter the size of the debt, can seem so distant and unattainable that the client abandons the aggressive debt repayment strategy altogether).

Simply put, different strategies for high-interest versus low-balance repayment plans are associated with different likelihoods of creating conditions that promote (or detract from) behavioral follow-through.

Furthermore, as noted previously, it is worth acknowledging that Ramsey is primarily targeting only those who need that first push to get started. By the time someone has made progress and established debt repayment as a consistent behavior, then it is possible that they may develop their own ways to maintain their motivation… while also shifting to a strategy of paying the mathematically more-optimal higher-interest debt first.

Ramsey’s 8% Distribution Rule

Another piece of advice that regularly irks advisors is Ramsey’s 8% rule (versus Bengen’s 4% rule) for taking retirement distributions.

Notably, Ramsey’s 8% rule can appear ambiguous, as it is not quite clear whether he intends to suggest that one can spend 8% of their portfolio each year or an initial 8% adjusted annually for inflation à la a Bengen-esque approach. In The Total Money Makeover, he states:

If you invest your nest egg at retirement at 12% and want to break even with 4% inflation, you will be living on 8% income.

Yet, on his website, he says:

…if you want to live on $40,000 a year, you need $500,000 in your nest egg. Take the amount you want to live on each year after you retire, divide it by .08, and that will give you what you need to have saved for retirement.

Both statements are ambiguous, but the former seems more suggestive of an 8% calculation each year, whereas the latter seems to imply more of a constant spending level.

In any case, since an annual 8% calculation is ridiculously easy to defend – since you literally cannot run out of money with an endowment style spending strategy – I'll address the harder to defend 8% rule applied in a Bengen-esque fashion.

While an initial 8% spending rate is likely higher than most advisors would prefer to see their own clients start with, it is also more defensible than many advisors may think.

First, the 4% rule does not account for the fact that most retirees do cut their spending throughout retirement. This naturally understates sustainable withdrawal rates. More fundamentally, however, the Safe Withdrawal Rate (SWR) methodology does not address the fact that people can (and do!) make adjustments as they progress through retirement. The 4% rule ends up being prudent in a historically worst sequence of returns, but for many other investors, much higher withdrawal rates would have been sustainable, and adhering to a 4% distribution strategy just results in (sometimes unnecessarily) large legacy values.

Let’s illustrate with an example.

Example: John is 65 years old, lives in Florida, and has just retired. He has a $250,000 traditional IRA and currently receives $1,500 in monthly Social Security income.

John is going to start out retirement, taking $20,000 (pretax) from his IRA, which is equivalent to an 8% initial safe withdrawal rate.

We’ll simulate John through historical scenarios using monthly returns going back to 1871. Furthermore, rather than using a static spending level, we will allow John to increase or decrease his spending depending on how markets, inflation, etc., have influenced his portfolio—making reductions when needed (e.g., when the forward-looking probability of success for the remainder of a plan falls too low) or increasing spending when it is prudent (e.g., when the forward-looking probability of success is high enough to justify higher spending).

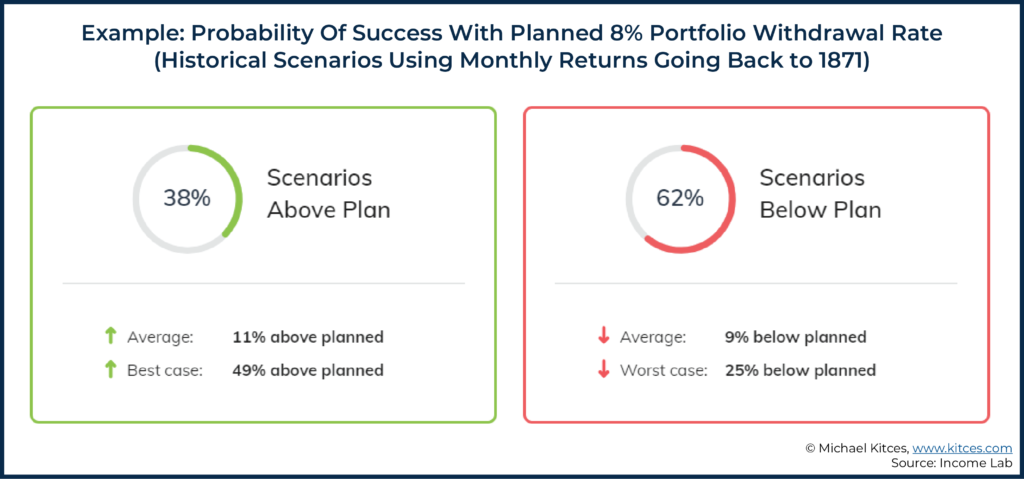

John’s results show that he would experience the following historical spending patterns when accounting for this more flexible analysis:

John was able to spend more than planned (i.e., the initial 8% portfolio withdrawal rate adjusted throughout retirement according to the retirement spending smile developed by Morningstar’s David Blanchett) in 38% of scenarios and less than planned in 62% of scenarios.

Not surprisingly, we do see that reductions were more common than increases, but we still see that more than one-third of scenarios actually led to spending more than the initial 8% withdrawal rate. On average, those scenarios provided about 11% more than planned and a best-case scenario of 49% more than planned.

Among the more common outcome (reflected by the 62% of scenarios below plan) of needing to reduce income, the average reduction relative to planned income was 9%, while the historical worst-case scenario was 25%.

To be clear, 8% is certainly an initial spending level higher than what many would consider to be ideal, but it doesn’t appear to be as disastrous as critics of Ramsey would suggest if we simply relax our assumptions to (a) acknowledge typical declining spending patterns throughout retirement, and (b) allow retirees to cut spending and make adjustments as needed.

While this is a case where I do not necessarily think that Ramsey is relying on any heavy analytics to support his suggested withdrawal rate (I think Wade Pfau’s depiction of how Ramsey arrived at this number is likely more accurate), there’s again still some real-world/behavioral wisdom embedded within this advice.

Imagine you are a modest retiree (the type that may be more likely to listen to Ramsey) that perhaps didn’t prepare for retirement quite as well as you should have. Retirement rolls around, and you realize 4% won’t come close to meeting your needs. Unfortunately, everywhere you look in the media, and among advisors, people are touting 4% withdrawal rates (or less), and you are feeling extremely stressed about the prospects of your retirement.

Then you listen to Ramsey, and he gives you permission to go up to 8%. Is that an ideal level of spending? No, but presumably, you are not in an ideal situation to begin with. Will it require some adjustment down the road? Very possible, but the alternative of a 4% rule will simply necessitate a potentially-even-more-dramatic adjustment immediately anyway. And in practice, maybe you don’t need quite 8%, and 6.5% will suffice (which also makes future adjustments at least a little less likely). In any case, Ramsey’s advice in this area is arguably better calibrated to reality, and a reflection that those who can adjust down to a 4% rule now can almost certainly start higher and adjust down later as well (with the caveat that in some cases, they actually won’t have to adjust down after all). It’s also worth noting that Ramsey’s listeners are going to skew differently on various demographics when compared to high-net-worth financial planning clients, and 30-year planning horizons may be longer than is realistic for many individuals.

And Ramsey’s suggestion actually aligns fairly well with Finke, Pfau, and Williams’ (2012) conclusion that 5-7% initial withdrawal rates may make sense for risk-tolerant individuals (i.e., individuals willing to accept some risk of depleting their portfolio and/or some risk of needing to make mid-course adjustments later to avoid that depletion) who have $20,000 of guaranteed Social Security income. Because Finke, Pfau, and Williams’ (2012) analyses did not account for the natural decline in spending throughout retirement (i.e., the retirement spending smile), that further helps close the gap between their upper end of 7%, and Ramsey’s suggested upper end of 8%.

Ultimately, in this case, Ramsey’s 8% rule could ‘nudge’ people toward greater peace of mind and psychological well-being in retirement by giving some assurance that withdrawal rates higher than 4% can be reasonable in a media environment that is otherwise largely screaming that they aren’t. And especially among Ramsey’s core demographic, this message may be particularly important. That doesn’t mean it necessarily applies to a typical advisor’s clients; but again, Ramsey is largely not speaking to most advisors’ typical clients.

Ramsey’s Advice On Student Loans

Ramsey gets a lot of flack from advisors for his advice on paying for college. While his advice for undergraduates is not too controversial (e.g., consider community college and/or in-state public universities, consider living at home to reduce living expenses, and work part-time so that you can pay for school without going into debt), his suggestions are often considered strained when it comes to financing expensive professional school (e.g., medical school, law, etc.).

Obviously, almost no one is going to pay for a $200,000 education working part-time while they go to school and without incurring any student loan debt. To be fair to Ramsey, while I haven’t listened to him extensively, I have never actually heard him claim that his suggestions on how to manage undergraduate education expenses also apply to medical school. He does put forward some strategies for receiving additional funding for medical school (e.g., pursuing a fully funded MD/Ph.D. dual-degree program, applying for financial support for those who commit to working with underserved communities, etc.), but he stops shy of saying that you shouldn’t go to medical school if you can’t pay for it without acquiring any debt. Nonetheless, “you can’t pay for medical school without debt” is a common criticism leveled against Ramsey.

This clip from The Dave Ramsey Show, in which Ramsey responds to a caller inquiring about how he might manage his medical school expenses, helps to clarify his stance on the issue:

…I would tell you there are actually ways to go to medical school debt-free. There’s a thing called the M.D./Ph.D. program, there are fellowships, there are scholarships, there are all kinds of things. Especially where your Mom has a lower income that qualifies you for all kinds of need-based things. That should open up a ton of doors for you.

And you got a 4.0 your first year. That should open up a ton of doors for you. So I think you’ve got too narrow a vision, and I want you to broaden your vision on where you might go to school, and where they might pay for it, and where you can get some scholarships, and the type of work you can do while you are doing your undergrad, and start investigating now how you’re going to do medical school debt-free.

Oh, there’s a lot of work for you to do, young man.

So while he doesn’t exactly denounce ever using debt to go to medical school, Ramsey clearly still favors options that could allow someone to graduate from medical school without debt.

Ultimately, though, expensive professional schools seem to be an edge case that doesn’t typically apply to most of his core audience. To some extent, Ramsey probably knows that, and it is probably no coincidence that he doesn’t have callers getting through to him with straightforward questions about whether it ever makes sense to take out a loan to go to medical school. However, again thinking about Ramsey’s purpose and who he is talking to, there might be a good reason for him to hold the line on the student debt issue even if it can’t be applied to all cases.

Here’s a snapshot of Ramsey’s listener demographics as published on his website as of November 22, 2020:

- 51% male; 49% female

- 23% age 18-34; 36% age 35-50; 33% age 51-69

- Average income: $88,000

- 40% of households with income greater than $100k

Based on these demographics, the Ramsey listeners thinking about college expenses are generally not going to be 18-year-olds who may be uniquely positioned to take advantage of networking at elite private institutions, and he’s likely not reaching many undergraduate students who are currently contemplating medical school.

To the extent that members of his audience (most of whom are over age 25) are thinking about college expenses for their own education, it is probably an MBA or master’s degree in some specialized field. It is likely someone who is already in the workforce and contemplating some sort of additional education. His audience’s average income is higher than the median household income in the US, but not by that much. And, while his website does not include detailed demographics to know for sure, I suspect many of the households with income greater than $100K are dual-income households with each spouse earning a fairly modest salary.

So why hold the line on not directly addressing the student-debt-for-medical-school issue? First, because he’s really not talking to the edge cases (i.e., those considering expensive professional schools); and second, because caving and admitting that there are some valid uses of student debt may not be the message his audience needs to hear, particularly in light of human behavioral tendencies that can make total abstention easier than moderation.

In Russell Roberts’ How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life: An Unexpected Guide to Human Nature and Happiness, Roberts describes insights from Adam Smith’s lesser-known work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments:

[Smith] urges us to follow the rules of justice with complete steadfastness; the more we do so, the more commendable and dependable we are. . . Smith’s emphasis on the importance of not deviating from the rules related to justice—always pay your debts, never steal, never betray your spouse—is a crucial aspect of confronting our self-deception. Once we decide that these rules can be relaxed in special circumstances, we’re on the road to finding ways to convince ourselves that what is good for me is good for you, too. Then there will be “no enormity so gross of which we may not be capable.” That’s not a mild warning; it’s a blaring siren.

Smith understands something deep about human nature with this warning. Hard-and-fast rules are easier to keep than rules that are slightly relaxed. The opposite should be true. You’d think abstinence would be much harder to keep than moderation. Yet, it is much easier to give up potato chips than to eat just one. Or a few. But shouldn’t it be otherwise? Shouldn’t it be easier to limit yourself to a few chips than to have none? Yet a few often leads to a few more. And a few more. Smith counsels us to keep the general rules of justice with the “greatest exactness.” They are “accurate in the highest degree, and admit of no exceptions or modifications.”

Given how hard Ramsey appears to have worked to avoid addressing this question head-on (e.g., with the vast amount of content he has published, why doesn’t a quick Google search reveal anything that directly tackles the issue of whether student loans should be used to pay for medical school?), it seems likely that he is aware that his philosophy doesn’t hold well for expensive professional schools.

But, since he’s largely not talking to these edge cases, to begin with, and because noting an exception could dilute his philosophy for those who are seeking the guidance of clearly defined boundaries, Ramsey stubbornly holds the line and just mostly avoids talking about the issue (or talks about related but different issues, such as how someone who aspires to go to medical school should fund their undergraduate degree or how someone with existing medical debt should get out of debt).

In other words, the issue of how to fund medical school is just not crucial to his core audience, and introducing a caveat just to accommodate folks who aren’t in his core audience to begin with can dilute the power of his philosophy for those who are within his core audience, so he stays true to his core audience.

The point here is, again, not so much about giving objective advice with the best financial outcome, but what message and belief system helps his particular audience make positive decisions. By avoiding the professional school caveats, Ramsey can perhaps do more to prevent opening “the floodgates of self-deception” for his core listeners who may be tempted to justify their own student debt without the means to be able to manage that debt.

And similar explanations could probably be provided for other edge cases. If a one-time strict adherent to Ramsey’s philosophy grows wealthy enough that it no longer strictly applies to them, then good for them!

In fact, a Ramsey apostate may renounce the basic ideology that may have helped them at one point once their needs grow more complex. But does Ramsey care? If someone gets to that point, hasn’t Ramsey already been successful in helping them get to the stage of relative self-reliance? Let the apostates drop their support of Ramsey’s philosophy when they are ready to do so. It is unlikely that in doing so, they are also going to drop the core behaviors that made them successful. They’re just going to come to realize that Ramsey’s philosophy is no longer well-suited for all of their needs.

Ramsey’s Preference for Active Management and Commissioned Advisors

While most of Ramsey’s advice aims to teach individuals how to make better financial decisions when managing their own money, he does advocate the use of commissioned advisors and actively managed funds when it comes to investing practices. This is an issue that garners Ramsey a lot of criticism, particularly among fee-only financial advisors. These issues are actually separate, but some aspects of both also go hand in hand.

First, it is important to remember here that Ramsey is largely engaged in ‘on-ramping’ listeners to good behaviors. He is trying to get people who haven’t used credit wisely to start doing so. He is trying to get people who haven’t saved to start doing so. He is trying to get people who haven’t invested in mutual funds to start doing so. He is trying to get people who haven’t worked with advisors to start doing so.

It’s all on-ramping, so his advice should be viewed through that lens, which may be different than, say, optimization.

It is also worth noting that getting people to change behavior is no small feat. In fact, in many respects, it is actually probably harder than optimizing the behavior that someone is already otherwise engaged in.

So why active management? I suspect this is in part due to the relative psychological attractiveness of both strategies. The evidence in favor of passive management is dry, boring, mathematical work. That doesn’t make it wrong, of course, but it’s just not as compelling. Passive management doesn’t have the upside allure (or avoiding downside allure) of active management. When financial advisors talk about fund managers, hearing that there’s a manager with some new strategy, or outlook, or technology, or whatever just feels more motivating to many consumers than taking what the market will give them.

And remember, Ramsey’s objective is to on-ramp his audience to change behavior. There’s room to optimize later. And over a long enough time horizon, someone who puts $5k into an actively managed US stock fund – even an underperforming one if the active manager doesn’t deliver – will still almost certainly come out ahead of someone who doesn’t feel compelled to pull the trigger on a(n unexciting) stock index fund and who stays in cash (or spends the funds!) instead.

A second (and more pragmatic) reason for active management is that Ramsey recommends advisors who work on commission and most loaded mutual funds are active products. But why commission?

First, commission-based advisors are more likely to be serving individuals within the demographics of Ramsey’s audience. Within our latest Kitces Research survey, we found that while fee models like hourly advising can, in theory, reach a broader segment of society, we still only see about 5% of hourly advisors serving typical clients with household incomes below the median US household income. Advisors within the insurance channel were the only segment to have any real sizeable reach of the US household income market below the national median, and even then, only 23% of insurance advisors described their typical client as falling within this category.

Furthermore, the mental accounting characteristics of commissioned products are actually quite favorable for getting someone to take action. When given the choice of paying $150/hour out of pocket or buying a product with a sales load that comes out of a client’s future income bucket, the commission product that pays with 'future’ dollars is much more attractive psychologically than paying an immediate fee out of what may already feel like currently constrained income.

Additionally, an up-to-6% front-end load on commissioned products actually provides a reasonable level of compensation for advisors to target and profitably serve a demographic that otherwise can’t pay for services out of their future income assets. For instance, while someone with a $1 million portfolio can pay $10,000 or more in ongoing fees that regulators will deem reasonable from their portfolio, someone with only $25,000 to invest would pay $500 per year or so (i.e., 2% AUM fee) on an ongoing basis. Few advisors are going to take that client on at $500/year, but there are advisors who might be willing to do some planning and investment work for a $1,500 front-end load.

In other words, commissioned products facilitate low-friction on-ramping, when Ramsey’s focus is on households that need help on-ramping (with as much behavioral nudging and as little friction as possible). Again, that doesn’t mean they are ideal products, but if the primary focus is on on-ramping, they are arguably better suited for getting the job done. If someone becomes successful and wants to optimize later, they can always switch to a more suitable product (or a more fee-oriented advisor) when they are ready.

So, combining these two psychological factors—low-friction on-ramping of commission-based products and services, and the more compelling story of active management—plus the simple fact that most non-commission advisors aren’t serving Ramsey’s demographic in a manner that consumers are able or willing to pay, is largely why he may be suggesting commissioned advisors and actively managed mutual funds. And the behavioral reasons for doing so are not insignificant.

Ramsey’s Financial Peace University

While Ramsey’s Financial Peace University (FPU) is not nearly as controversial as some of Ramsey’s advice covered above, it is still worth taking a second to acknowledge just how powerful the program is from a behavioral perspective.

Financial Peace University is a nine-week course that covers basic financial topics (establishing an emergency fund, getting out of debt, saving for retirement and college, etc.). The courses are based on a curriculum developed by Ramsey and led by a coordinator who guides members through the course. There are also group activities (e.g., cutting up credit cards) that can be quite memorable.

Human-to-human connection can be incredibly powerful in actually getting people to change behavior. The social reinforcement and peer support from FPU groups can be tremendously helpful for working through the difficulties of changing one’s behavior.

With FPU, you have a group that meets once per week (or more) and encourages each other, reinforces group norms, and holds each other accountable. Group rituals such as cutting up credit cards further serve to reinforce the type of rigid ideology toward debt that can be useful for those that desperately need out of it.

The FPU enrollment structure itself also has some desirable characteristics, such as requiring a modest fee to weed out tire kickers and creating a group that is motivated to make some change.

Again, the point is not to suggest that everything taught in FPU is the absolute truth or optimal way of addressing various topics. But for those who are looking for the type of support it provides (including the over 5 million families who have gone through FPU and the over 14 million weekly listeners who tune in to listen to Ramsey), it is arguably the most powerful (and most impactful) method of delivering financial education ever created.

Ultimately, Dave Ramsey is someone who draws a lot of criticism from financial advisors. If we look purely at his advice from a technical perspective, then much of the criticism is arguably quite valid. However, getting overly focused on the technical issues largely misses the point.

Ramsey is in the business of helping people change their financial behavior for the better, particularly those who need to get started on a different path than the one they are currently on (or motivating them from inertia to action in the first place), and being ‘right’ doesn’t necessarily help motivate people to make the first step of change. When we step back and evaluate what he has created from that perspective, there’s real behavioral ingenuity to his advice and the systems he has created to deliver that advice.

Disclosure: Derek Tharp is a Senior Advisor at Income Lab, which was used to model the spending outcomes in the example included in this article.